The puzzle canon in Baroque and pre-Baroque times was well known to composers and theorists as a pleasant source of amusement as well as a means for developing their awareness of counterpoint. It usually took the form of a single melodic line accompanied by an enigmatic inscription hinting at a procedure which, if applied correctly, would give the correct solution to complete the canon.

In the annals of the contrapuntal literature, however, there exist puzzle canons which boast a multitude of solutions. This leads one to believe that the puzzle canon, together with its inscription, points not to a single answer, but to a procedure as such, and in this way challenges the pursuant to a broader awareness of the possibilities inherent in a musical theme.

An interesting example is found in Canon 10 of the recently discovered addendum to the Goldberg Variations by Bach, titled Fourteen Canons (BWV 1087, Bärenreiter BA 5153, 1976), edited by Christoph Wolff. Over the first eight notes of the Aria ground bass (G  E D B C D G) Bach presents 14 puzzle canons, solutions to which are provided by Wolff. If one observes carefully, however, not only the music which is given, but also the subtle inscription in Canon 10, one arrives at an entire family of possibilities, some of which are perhaps more musical than the obvious one provided by Bach.

E D B C D G) Bach presents 14 puzzle canons, solutions to which are provided by Wolff. If one observes carefully, however, not only the music which is given, but also the subtle inscription in Canon 10, one arrives at an entire family of possibilities, some of which are perhaps more musical than the obvious one provided by Bach.

The autograph in Bach's personal copy of Part IV of the Clavierübung (Paris, Biblioteque Nationale, MS. 17669) contains the following inscription accompanying Canon 10: "Alio Modo, per syncopationes et per ligatures," which literally translates to: "By means of ties and suspensions." The "Alio Modo" however, translates to: "In another way," which can be taken as a hint to the pursuant to "try yet another type of solution." Bach then proceeds to give us two versions of the canon. The first is a counterpointed theme against the Aria ground (written in letters below the theme) and the second is the same theme transposed down two octaves plus a third and inverted melodically, with the Aria ground appearing in letters transposed up a fifth, occurring above the theme and also inverted melodically. Thus, Bach has affected three procedures, namely:

anda) Double Counterpoint

b) Melodic Inversion

c) Vertical Shifting

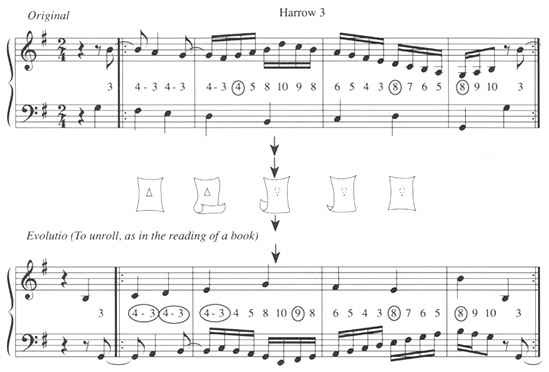

Accompanying the second version is the word "Evolutio." We know from other works of Bach (i.e., The Musical Offering) that he was fond of word games, and this is no exception. "Evolutio" means, to unroll as in the reading of a book; but it also means to change or evolve. Taking literally the first of these definitions—to unroll—we obtain a visual stunt which Bach has effected with the music; by taking the first version, turning the page over and reading it through the light, we arrive at the second version (see Example 1).

Example 1.

This procedure is reminiscent of other visual quirks found in the puzzle canon literature, such as the crab canon which can be read from left to right or from right to left; and the inverted crab canon, which can be read normally or with the page turned upside down for the same results.

Taking the second meaning of "Evolutio"—to change, or evolve—we are faced with the possibility of imposing ourselves on the music and effecting its metamorphosis. Three facts tell us this: the first is that Bach has already given the solution to his own canon in the form of the Evolutio; the second is that not only this solution, but also the first version contains contrapuntal errors (which will be pointed out later); and the third is the enigmatic inscription which tells us to move on. For the purposes of this study, we will use only the three parameters (Double Counterpoint, Melodic Inversion, and Vertical Shift) provided by Bach to arrive at new solutions.

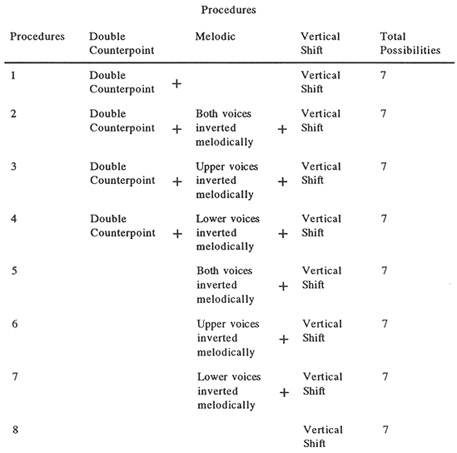

Each of these procedures can be effected alone or in combination with the other two. The list of all possible combinations is provided in Example 2.

Example 2.

Vertical Shifting, the widening or narrowing of the vertical distance between the voices, is applied with the other procedures simultaneously as well as separately. This adds up to seven possibilities for each procedure—an overall total of 56 (out of which 11 have been retained as musically plausible solutions, based on Baroque practices). The numbers to the left of the procedures sheet correspond to the solutions in Example 3.

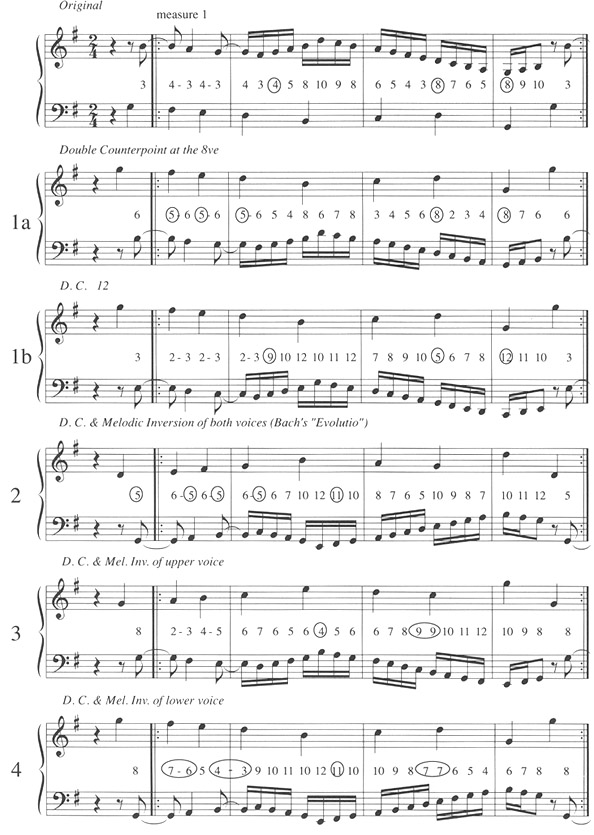

Example 3

Regarding the solutions (Ex. 3), the error chart accompanying the solutions is based on strict academic counterpoint, with the belief that a canon of such short dimensions is intended pedantically, as is also the majority of the puzzle canon literature. In each solution, the intervals between the voices are notated as numbers (disregarding octave separations for convenience's sake). All suspensions, correct or not, are notated with a dash between the numbers. Circled numbers show where the errors occur. The type of error is delineated immediately to the right in the error chart. Errors involving suspensions include incorrect preparation and/or resolution of syncopated dissonances. The reader's familiarity with the other errors is assumed.

Error Chart

| Faulty treatment of suspensions |

Consecutive perfect consonances |

Accented ascending passing- notes |

Consecutive dissonances |

Parallel perfect consonances |

Similar motion to perfect consonances |

Leaps into dissonances |

Total Errors |

|

| original | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||||

| 1a | 3 | 3 | ||||||

| 1b | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||||

| 2 | 1 | 3 | 4 | |||||

| 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||||

| 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 | ||||

| 5a | 1 | 3 | 1 | 5 | ||||

| 5b | 3 | 3 | ||||||

| 6 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 | ||||

| 7a | 1 | 3 | 4 | |||||

| 7b | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | ||||

| 8 | 3 | 3 |

Comments Pertaining to Solutions

Original

This is Bach's first version, which already contains two errors. Worthy of notice are the notes of the upper voice in the second bar, which are the inverted and diminuted (4: 1) first seven notes of the ground bass. There exists only one skip in the upper voice, two in the Aria ground.

Solutions la, b

Of these two double counterpoint solutions, the one at the 12th seems the better with only two errors, both of which occur in the precise corresponding places as in the original.

Solution 2

This is the Bach "Evolutio" which Wolff chose to include as the only solution for the first edition. The preponderance of parallel fifths (occupying exactly half of the ground bass theme) as well as the presence of a total of four errors (twice that of the original) leads one to suspect that Bach intended this joke to prod the pursuant to find more musically sound solutions. (See my article, "Bach the Humorist," in vol. 25, 1985 of College Music Symposium.) It should be noticed that any solutions involving the ascending (melodically inverted) version of the syncopated voice will manifest errors, since all dissonances in Baroque music resolve downward. This leaves only the 6-5 possibility for upward-moving syncopations, but since there are three consecutive syncopated notes, the parallel fifths arrive unbeckoned.

Solution 3

Of the 11 solutions provided here, this is perhaps the most musically and academically sound. The first measure contains varied suspensions, and the errors revealed are often encountered in Bach's music. Sharping the d in the lower voice of the second measure lends a subtle e-minor shade to the piece.

Solution 4

This solution shows what happens when the ascending version of the syncopated voice produces upward-resolving suspensions, in this case the 7-6 and 4-3 suspensions. Upward-resolving suspensions, though rare, are encountered in Bach's music (see, for example, measure two, beat four of the a-minor Prelude from the Well-Tempered Clavier, Book Two for an upward-resolving 4-3 suspension).

An interesting quirk manifests itself in this solution: keeping the vertical relationship of the voices intact, but shifting them together to the left by one eighth-note corrects the faulty 4-3 suspension by making the upper voice the syncopated one (see Ex. 4).

Example 4.

With this notation change, there are now only three errors, though the constant syncopation in the upper voice is unusual.

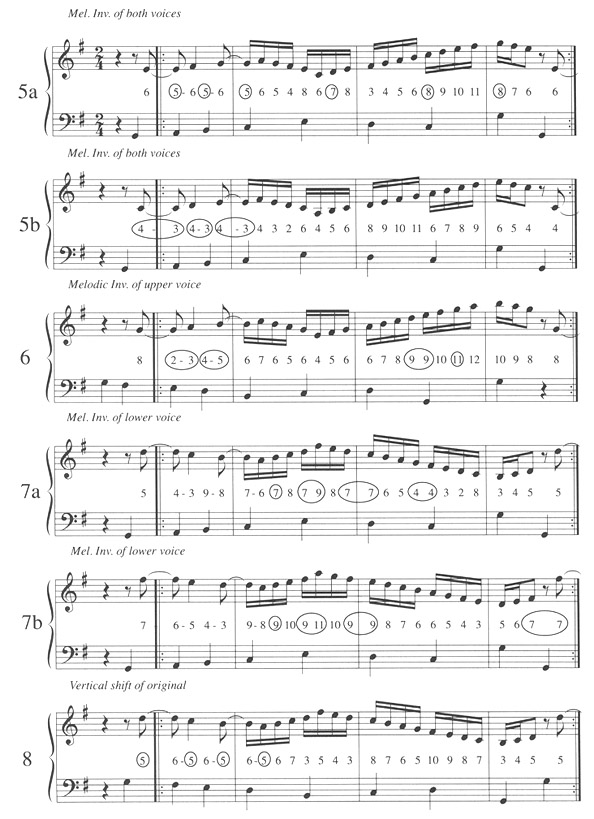

Solution 5

5a) This solution merely shows another example whereby the ascending syncopated voice produces a chain of 6-5 resolutions.

5b) Shown here is a solution whereby upward 4-3 suspensions result. There are less errors here than in the Bach "Evolutio," and the contrapuntal fabric is not destroyed by any parallel fifth chains.

Solutions 6 and 7a, b

These solutions are retained in order to show the results of the particular procedure of melodically inverting only one voice. The quantity of errors found here is the same as the quantity of those found in the Bach "Evolutio," producing not the most musically satisfying examples.

Solution 8

Here is a mere vertical shift of the original, exhibiting the unsatisfactory parallel-fifth chain, but only three errors.

Although beyond the scope of this work, one example should suffice to show the effects of adding one more parameter: horizontal shifting. Example 5 shows the results of this procedure applied to Solution 5b.

Example 5.

The upper voice is shifted one eighth-note to the right, producing two accented passing notes, one parallel fifth, and one unresolved fourth, totaling four errors (the same total as 5b). As there are 15 possible placements of the upper voice against the lower horizontally (at each successive eighth note), the procedure of horizontal shifting combined with the other procedures makes 840 possibilities apparent! With each new added procedure (that is, diminution, augmentation, retrograde, etc.), the possibilities increase dramatically.

The old counterpoint masters understood that the development of technique was largely a matter of the awareness of possibilities. It was natural to their thinking to squeeze as much out of an idea as they could, for they were required by their positions to write music rapidly, and to solve complicated technical problems without stumbling. They operated faithfully on the premise that "Beauty yields beauty," and thus, from small musical ideas built edifices of music which exemplified a startling economy of means. Usually their methods involved the working out of ideas prior to their inclusion in the piece, but they realized also the importance of developing ideas already given. It was for this latter purpose that the puzzle canon came into existence, of which Bach's Canon 10 is but a modest example. By restricting ourselves to the parameters given within Bach's canon, we are able to ascertain a reasonable number of solutions. In keeping with the spirit of the puzzle canon however, one should realize that the importance of the puzzle canon lies not in the type or number of solutions discovered, but in the awareness gained while discovering them.