Selle v. Gibb and the Forensic Analysis of Plagiarism

Written by M. Fletcher Reynolds

Symposium Volume 32

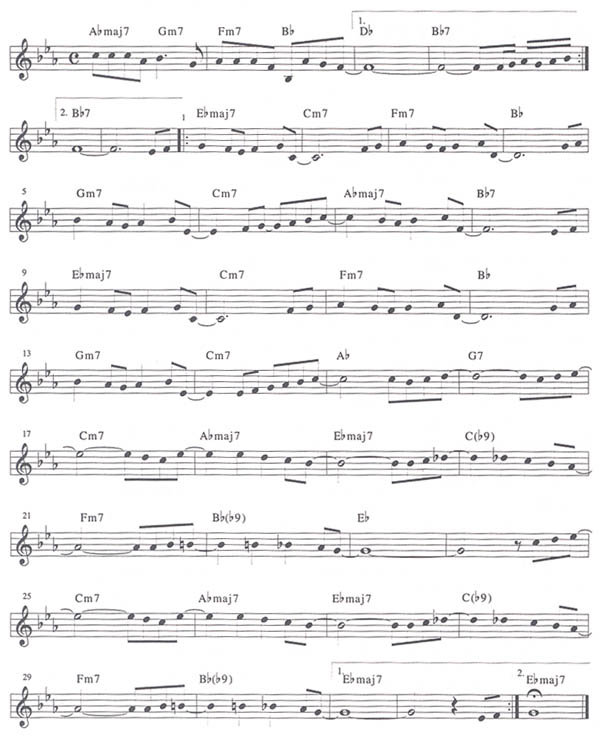

Ronald H. Selle, an Illinois antique dealer with a master's degree in music education, composed popular and religious songs and played locally in a small band. One day in 1978 while Selle was working in his yard, a cassette player belonging to the teenager next door blared out what Selle recognized as the music to his song "Let It End" (Figure 1).

Figure 1 "Let it End"

Reprinted by permission. Copyright 1975 by Ronald H. Selle.

Since writing the song in 1975, Selle had sent the lead sheet and a home recording to fourteen publishers. Eleven publishers had returned the materials; three never responded. Selle filed suit against Barry Gibb, Robin Gibb, and Maurice Gibb (a/k/a the Bee Gees), Phonodisc, Inc. (a/k/a Polygram Distribution, Inc.), and Paramount Pictures, accusing them of misappropriating his music in the hit song "How Deep Is Your Love" (Figure 2).

Figure 2 "How Deep Is Your Love?"

Reprinted by permission. Words and Music by Barry Gibb, Maurice Gibb and Robin Gibb. Copyright © 1977 by Gibb Brothers Music. All Rights Administered by Careers-BMG Music Publishing, Inc. International Copyright Secured. All rights reserved.

The case was tried to a jury in 1983.1

Evidence of infringement was presented at trial by the plaintiff's expert witness, a music theorist who analyzed the two works to determine whether Selle's work had been copied by the Bee Gees. For reasons explained below, the defendants' experts did not testify, although they were present at trial and prepared to take the stand. The Selle case illustrates some of the pitfalls awaiting the music analyst who ventures into court and, on a more general level, the very real difficulties of analyzing music to determine authorship and presenting one's analysis in a form that lay persons can comprehend. A forensic analyst must never lose sight of the true issues to be addressed, both legal and musical. Yet a survey of plagiarism cases reveals that music experts have routinely failed to give adequate consideration to essential aspects of their task. The analysis introduced into evidence in the Selle case typifies the practices of many past and current expert witnesses—practices which often result in the introduction of insufficient or irrelevant evidence. Obviously, the lay trier of fact2 who relies on such evidence may be led to reach an incorrect verdict.

A solution can only be achieved when lawyers and musicians better understand the demands of each other's discipline. Before discussing the Selle trial and the analytical evidence presented, the reader should know what must be proved to sustain a claim of plagiarism and what the expert witness's role is in presenting or refuting this proof.

Proof of Copyright Infringement

Copyright law grants an exclusive right to authors to control the copying and distribution of their work. It includes the exclusive right to produce the work in copies, to prepare derivative works such as musical arrangements, to distribute copies to the public, and to perform the work publicly. The scope of copyright protection is limited to the author's original expression; it does not protect the more abstract idea that forms the basis of the work.3 Further limiting protection, the "fair use" doctrine provides that the author's work may be reproduced for, among other purposes, criticism, scholarship, and news reporting.4

Some commentators refer to copyright as a monopoly, but copyright law does not grant a true monopoly. Unlike patent law, a copyright does not protect the novel item; it merely protects the original author from having his work copied. In theory then, and perhaps only in theory, a composer may write a work identical in every way to another pre-existing work and enjoy the same copyright protections as the earlier composer. As long as the latter composer does not copy the earlier work, none of the first composer's exclusive rights are violated.

Infringement is simply any violation of the author's exclusive rights.5 The Copyright Act provides no additional definition of "infringement." Thus, in a copyright infringement lawsuit, the court must determine (1) whether the first author holds a valid copyright, (2) whether that author's work is original, (3) whether the original work has been copied, and (4) whether the copying violates the author's exclusive rights or whether it is a fair use. Ronald Selle's claim against the Bee Gees was one of plagiarism—that the Bee Gees copied his work and passed it off as their own. Selle first presented evidence that he held the copyright in his own work "Let It End." The defense did not contest the existence of Selle's copyright. Thus the trial testimony focused on the remaining, contested legal issues: whether Selle's work was original; whether the Bee Gees copied Selle's work; and, if they did, whether that copying constituted a violation of Selle's exclusive rights.

Expert witnesses testify under special evidentiary rules. Most witnesses can testify only to facts of which they have personal knowledge. But the rules of evidence provide that a person with specialized knowledge or skill may give opinion testimony if it will be helpful to the trier of fact. In complex or unfamiliar matters on which the jury has no base of knowledge, expert testimony can be decisive. Trial often becomes a "battle of the experts" in which two authorities give opposing opinions. In such cases, the jury verdict may well turn on the relative credibility of the experts and the experts' ability to make their reasoning accessible to the lay person.

The judge applies evidentiary rules to determine what evidence the jury may hear. Judges deal with cases of all kinds and hear expert testimony on a multitude of issues. Although the judge is usually a lay person in the expert's field, he or she often knows something about the expert's methodology. A real estate appraisal or medical diagnosis, for example, must adhere to certain generally understood principles, and the judge can usually distinguish science from superstition and disallow useless or misleading testimony. In music plagiarism cases, however, even an otherwise well-informed judge usually has little understanding of what music theorists do, and will find no legal authority to steer evidentiary decisions in the right direction. Quite the contrary, the sparse legal writings on music are filled with truly astonishing misinformation.

To prove copying, the plaintiff must show "access" plus "substantial similarities."6 Plagiarism is rarely witnessed, and so the requisite evidence of copying is necessarily circumstantial. Access may be reasonably easy to show where the original work has enjoyed popular success and exposure. The term "substantial similarity" is nowhere defined. The jury must determine whether the similarities are sufficient to warrant an inference of copying. Litigants commonly rely on the testimony of experts to help the jury assess the significance of similarities or differences. A second method of proof allows the jury to infer access where a qualified expert testifies that there are "striking similarities." The law defines striking similarity as that kind of similarity which can only be explained by copying rather than coincidence, independent creation, or common source.7 Lay testimony is inadequate to show striking similarities.

Proof of copying alone is not sufficient to prove infringement. The plaintiff must also prove that the copying rises to the level of misappropriation. If the copying is a fair use, it is not a misappropriation. Nor is it a misappropriation to copy something other than the author's original expression. The defendant may claim that similarities arise because both he and the plaintiff copied from a common source. If so, then what was copied is not the plaintiff's original expression, and the plaintiff cannot complain. The prior common source defense offers many good arguments to defendants, especially in cases involving musical styles that employ standard formulae, and therefore experts must consider not only similarities between the two works at issue but also similarities with prior art. The landmark case of Arnstein v. Porter, in which Cole Porter defended charges of plagiarism, phrased the misappropriation question as "whether defendant took from plaintiff's work so much of what is pleasing to the ears of lay listeners, who comprise the audience for whom such popular music is composed, that defendant wrongfully appropriated something which belongs to plaintiff."8 Thus stated, misappropriation addresses aesthetics, but it should be understood to address issues of philosophy, economics, and public policy as well.

The Trial

The Selle case was tried in the court of the Honorable George N. Leighton, United States District Judge for the Northern District of Illinois. Selle's counsel, Allen C. Engerman, outlined the plaintiff's case in his opening statement to the jury. Experts would testify to striking similarities between the two songs. Of thirty-four notes in the opening eight measures of "Let It End" and forty in the corresponding measures of "How Deep Is Your Love," twenty-four were identical in pitch and thirty-five were identical in rhythm.9 Because no link was ever established between the Bee Gees and any of the publishers to whom Selle had sent his song, access could not be shown. Instead, the plaintiff would show striking similarities to rule out the possibility of independent creation.10

Robert Osterberg, representing the Bee Gees, countered. Copying was the key word, and similarities alone could not show copying. Copyright does not grant a monopoly on a particular musical expression; it only prevents another from copying that expression. Coincidental similarities, attributable to the limited number of notes in the vocabulary of popular music, provided no basis for legal redress.11 Selle could not establish copying or any opportunity for the Bee Gees to have heard his song. Selle's song was never recorded or performed where the Bee Gees could have heard it, and the Bee Gees had a strict policy of not reviewing unsolicited material.12 Furthermore, the two songs had little in common. Plaintiff's song, according to Osterberg, was predictable and amateurish—the Bee Gees', complex and sophisticated. "How Deep Is Your Love" reflected the musical genius of one of the most outstanding songwriting groups in popular music history.13 "Let It End" met with universal rejection, "How Deep Is Your Love" with immediate and phenomenal success.14

Following opening statements, plaintiff began his case in chief. Direct examination of Selle placed the basic facts in evidence.15 He explained to the jury how he wrote his song and the efforts he made to market it. On cross-examination, Osterberg confronted him with examples of prior art, works which predated both songs at issue. He pointed to similarities between the works at issue and other Bee Gees songs. Selle's song, Osterberg suggested, also resembled the Beatles' song "From Me to You." Were these similarities between prior art and your song, Osterberg asked Selle repeatedly after identifying each example, the result of coincidence?

Selle claimed the Bee Gees took two key sections of his work, the opening (Theme A) and ending (Theme B). He admitted that the middle section of "How Deep" was original. Both key sections involve a motive treated sequentially. Osterberg sought Selle's admission that sequential repetition entails only the mechanical transference of the motive up or down in pitch and, therefore, that each subsequent statement was not an independently significant creative act. Selle characterized sequential repetition as only one option among many. Theme A employed an ascending sequence while Theme B's sequence descended.16 That choice required a creative act. But Selle admitted, inaccurately, that a composer had only twelve options once the decision was made to treat the motive sequentially.17

Plaintiff's expert, Arrand Parsons, possessed impeccable credentials as a theorist and musicologist. He had taught at Northwestern University since 1946, chaired the music theory department for five years, and published writings on music analysis.18 Although he had never made a comparative analysis of two popular songs prior to this case, he believed he was qualified to testify because he was first of all a lifelong student and teacher of music theory, a discipline which involves analysis.19 Questioned about his focus on more serious music, he replied that the analytical process would not vary if the music were pop, country, rock, or classical.20

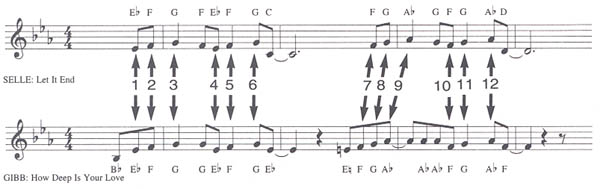

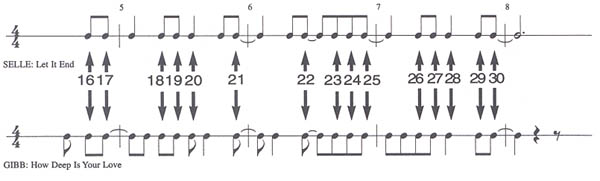

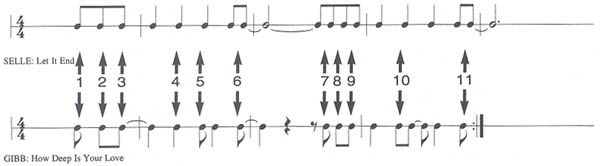

Parsons began his direct testimony with a short lesson in music fundamentals. He then proceeded to explain how these two songs were so strikingly similar that they could not have been written independent of one another.21 Jurors held their personal copies of Exhibits 18 and 19 (Figures 3 and 4), printed cards with plastic mylar overlays. What was identified as Theme A of each song was written on the card on a separate staff, one above the other. Exhibit 18 covered the first phrase of Theme A, and Exhibit 19 covered the second.

Figure 3 Exhibit 18

Figure 4 Exhibit 19

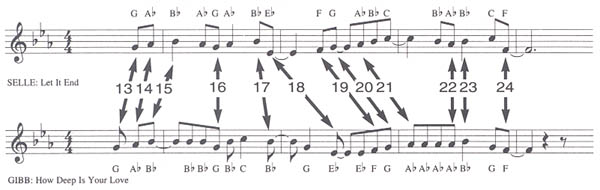

Where the pitches matched at or near the same rhythmic position, those notes appeared in red on the mylar overlay with red arrows drawn between them.22 The arrows were numbered 1 through 24. Another copy of the exhibits was placed close to the courtroom piano so that Parsons could play and point without having to move. Parsons explained Exhibits 18 and 19, note by note.23

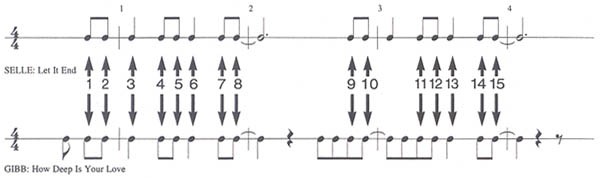

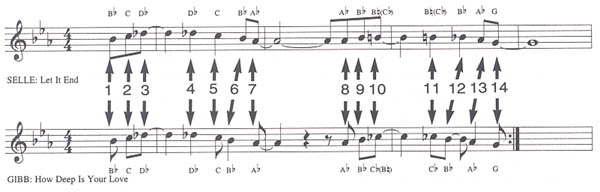

Exhibits 20 and 21 showed a rhythmic comparison of the same material (Figures 5 and 6). The corresponding ties at the end of measures 1, 3, 5, and 7 were displayed in turquoise.24 Thirty red arrows appeared on the mylar overlays of Exhibits 20 and 21.25

Figure 5 Exhibit 20

Figure 6 Exhibit 21

The process was repeated for Theme B. The pitch comparison, Exhibit 23 (Figure 7), showed fourteen red arrows in four measures. The rhythms of Theme B, Exhibit 24, (Figure 8), matched at eleven points.26 At each juncture, Parsons testified that similarities were so striking and vivid that, based on his experience and background in music theory and analysis, independent creation was precluded.

Figure 7 Exhibit 23

Figure 8 Exhibit 24

Parsons noted additional similarities. Theme A occurs at the beginning of both songs, Theme B at the very end.27 Theme B is not related to Theme A; as two independent musical thoughts or melodic thoughts, their composition would require two creative acts.28 Based on a structural analysis of the two songs, coupled with his detailed analysis of the melodies of Themes A and B, Parsons believed and reiterated that the two songs could not have been created independently. He did not know of any two musical compositions by two different composers that contain as many striking similarities as exist between these two songs.29

Osterberg began his cross-examination by questioning Parsons's choice of source material for his comparisons. Parsons had used the copyrighted lead sheet of "How Deep," but the Bee Gees do not read or write music. They claimed to have written "How Deep" through a process of trial and error while gathered at the piano with a cassette recorder. Osterberg characterized the work tape of that session as the best evidence of what the Bee Gees had written and how they wrote it. A transcriber committed the song to writing only after the composition process was completed and a demonstration tape made. Over objections, Osterberg tried to establish that Parsons had based his comparisons on secondary materials.30

Parsons had formalized his opinions after completing his analysis of the two songs a few years before trial. His pretrial written report, which matched the conclusions stated in his direct testimony, had been made without ever examining other songs written by the Bee Gees.31 Although Parsons claimed to have listened to some of the Bee Gees' music, Osterberg named eighteen of their albums, asking each time if Parsons had listened to that particular album. In each case, Parsons answered no.32

After Parsons reiterated that he had never before compared popular songs, he made a critical admission: he did not know whether or not there is a great deal of similarity between songs in the popular music field.33 Although certainly qualified to analyze similarities, Parsons's answers raised a question as to whether he could judge how striking those similarities were. No fact witness would substitute for Parsons on this inquiry; only an expert can testify that similarities should be considered striking in the legal sense. For the plaintiff to prevail, Parsons needed to state that the similarities could result only from copying. If he could not judge the uniqueness of the similarities of the two works at issue compared to the many similarities commonly found in popular music, then he could not testify as to their significance. And if he had not familiarized himself with the relevant stylistic elements of popular music, he could not know which similarities were unique to the two songs at issue and which were merely idiomatic and unprotected.

Asked by Osterberg to define his use of the term "striking similarity," Parsons stated that it exists where pitches and rhythms coincide.34 Osterberg continued:

Q . . . [Y]ou have used it several times during the course of your initial presentation. I would like to know whether that's the sole meaning you attribute to the phrase striking similarity.

A Those were the two points I used in my report because the question was one of melodic comparison. . . .

My assignment here was to compare the two melodies under consideration. That is what I did.35

Judge Leighton wanted more. At the end of cross-examination, he put the question to the witness himself. Was Parsons familiar with the expression "striking similarity" before he undertook the analysis of these two songs? Parsons responded that he was not previously aware of the legal implications, but he had used the term in his musical instructions.36

The judge's question was critical particularly in light of Parsons's hedging during Osterberg's questioning on the existence of copying. For example:

Q Is it your opinion, Mr. Parsons, that the only way the B Theme of "How Deep Is Your Love" could come about was as a result of copying Mr. Selle's song?

A I, I don't believe—put it positively. I believe that the Bee Gees' song, with these elements which we have described in common with the Selle song, I believe that the Bee Gees song could not have come into being with the—I must correct that. Because that is again dealing with a conjecture.

I believe that the elements, if I may just wipe that away and start again, because it's gotten twisted up.

I believe that the elements which are in common between the two songs in question are of such striking similarity that the second song could not have come into being without the first.Q By that are you saying without reference to the first? Are you saying without reference to the first? I don't—can you explain what you mean by couldn't have come into being without the first?

A Could not have been composed without the first.

Q I am asking whether you are saying that it couldn't have been composed without seeing the first song, without referring to it, without copying it? What is your testimony?

A All of those things you described, copying, having seen it first, I have forgotten the others, I, have no way, that is conjecture, I have no way of knowing whether it was seen, it was—I only know that the two songs have so much in common that it is—that the—that it precludes—this is too long. That the second song has so much in common, that is—let's get the names right. That the Bee Gees Brothers' song has so much in common with the Selle song that I cannot see, I cannot believe that they were created independent of one another.

Q Referring to your deposition, Mr. Parsons, page 89, commencing at line eight, I asked you the following question: "Q. Do you think the only way it could have come was a result of being copied from Mr. Selle's song?" "A. I could not answer that because I wouldn't know," end quote, line 11. Is that still an accurate answer today?

A I, would not know. Yes, I would answer it the same.

Q So you can't answer the question because you don't know?

A No.37

The legal test is precise. Because plaintiff could not show access, his case depended on showing striking similarities such that coincidence, independent creation, and common source were all precluded. Parsons seemed to be using the term "striking similarity" loosely and would not state unequivocally that the similarities could result only from copying. The question of striking similarity goes to the heart of the composition process; it asks how the defendant composer could achieve the result he did. In that sense the question is a purely musical one, and the court would have recognized Parsons as qualified to answer. However, without familiarity with the popular music field, that field's standards, and the differences of purpose between classical and popular composers, Parsons could not answer relevant questions concerning the musical style. He did not understand the aesthetic or economic motivations of popular composers. Osterberg exploited this lack of knowledge and cast doubt on whether Parsons knew the significance of the similarities he had found. When Parsons failed to state unequivocally that the similarities proved a composition process that relied on copying, his use of the term "striking similarity" became legally meaningless. Without expert testimony on this point, plaintiff could not meet his burden of proof. The judge commented to the attorneys in chambers prior to giving jury instructions that Parsons had not satisfactorily answered his question.

THE COURT: Since he isn't here let me tell you why I asked him. I wanted to know from him whether the expression "striking similarity" is found in the works of analysts of music—that's what I wanted to know—or in his vocabulary, as I suspect, is an expression that began with his work in this case. He told me, I thought, that the expression is found in the works of music analysis. That's what he said. I wasn't satisfied the way he answered my question, but I didn't want to pursue the matter further so I left it.

MR. OSTERBERG: I thought he said he had used it before, but then I had asked him to define what he meant by striking similarity. His definition does not correspond to the legal definition.38

Another of plaintiff's expert witnesses, Harold Gelman, waited to be called in from California. Plaintiff, however, elected to hold him in reserve for rebuttal and called only one more fact witness, Maurice Gibb. In his deposition, Gibb had been asked to identify a short excerpt prepared by one of plaintiff's experts. It was played again in court, and Gibb again identified the excerpt as coming from "How Deep Is Your Love." Engerman then read the stipulation into the record that the excerpt was "Let It End."39 The press considered this a most dramatic event, and it was widely reported.40 With a favorable impression left on the jury but no definitive testimony on striking similarity, plaintiff rested his case.

The defense concentrated on the work tape that purported to document the composition of "How Deep Is Your Love." The writing session took place in France at the Chateau D'Herouville in January 1977.41 Barry Gibb was called upon to authenticate and explain the tape.42 Albhy Galuten, the Bee Gees' record producer, testified that he was present at the composition session.43 He had played piano and made minor suggestions.44 Maurice and Robin Gibb corroborated this account of their song's creation.

Engerman tried to cross-examine Robin Gibb on discrepancies in the defendants' collective account of the tape's creation, but the judge disallowed it on the grounds that such questions went beyond the scope of direct examination.45 The judge noted that the witness had only been asked whether he was a coauthor and whether or not he ever heard about "Let It End" before he participated in the creation of "How Deep Is Your Love."46 Engerman explained at side bar (out of the hearing of the jury) that, although it was admittedly a work tape, his purpose was to show that the tape might not be the product of the initial creative effort.47 He argued that there was a question as to when the work tape was created. It might be a work tape merely to refine a song. Engerman wanted to show that the work tape might have been made after the Bee Gees left the chateau and after the music was first submitted to the Copyright Office.48 The judge sustained Osterberg's objections to this line of questioning.

The defense rested. In a surprise move the defendants elected to forego their experts. Osterberg had surmised from some of the judge's comments to the attorneys in chambers that the judge did not think Parsons's testimony established the requisite level of striking similarities.49 If the defense put on its own experts, then the plaintiff could counter with rebuttal experts, and those experts might cure the defects in Parsons's testimony. Further, proceeding with the defense would raise issues of fact for the jury to decide; as it stood, one issue of law, the adequacy of Parsons's testimony on striking similarity, was overriding. Nevertheless, the judge refused a defense motion for a directed verdict.50 Striking similarity, he said, was a question for the jury. However, he observed outside the presence of the jury that it was obvious to him that the first eight measures were not strikingly similar.51

Plaintiff could not at this point put Gelman, his second expert witness, on the stand to show striking similarities, because plaintiff had rested his case and there was no defense expert to rebut. Plaintiff's counsel considered presenting expert testimony to show that the work tape introduced by defendants did not represent the initial creative effort, but he apparently realized that such testimony would be ineffective. Composition is a mental process, and a recording provides poor evidence of the composer's thoughts. The jury probably viewed the tape with justifiable skepticism; the tape certainly did not disprove copying. But unreliable as that tape might be as evidence of independent creation, no expert was likely to prove that the Bee Gees had heard Selle's song prior to the recording session at the chateau or, better, that the session was a fraud. In the end, plaintiff never rebutted the work tape's feeble contribution to showing independent creation.

Jerrold Gold, plaintiff's co-counsel, summed up the case for the jury. Parsons had testified to striking similarities and the defense had presented nothing to refute his conclusions.52 Defendants' evidence of independent creation was inconsistent and inconclusive.53 Those in the entertainment world hear many songs; the Bee Gees might have copied Selle's subconsciously.54

Osterberg in his summation reminded the jury that Parsons used a definition of striking similarity at odds with the legal definition. Parsons would not rule out the possibilities of independent creation, coincidence, and common source.55 Although skilled in the analysis of classical music, Parsons clearly knew little about popular music. Because of this critical gap in his knowledge, he could not judge the significance of the similarities. Therefore, when Parsons said he did not know of any two musical compositions by two different composers that contain as many striking similarities as exist between these two songs, he drew a conclusion beyond his expertise. Osterberg implored the jury to substitute their own superior knowledge of popular music for the opinions of Parsons.56

Engerman, in rebuttal, completed plaintiff's summation on a more personal note. Even though the defense experts were seated at counsel's table and introduced to the jury at the start of trial, Parsons was the only expert to testify. His testimony had been eloquent and beyond impeachment. A professional such as Parsons relies on his reputation and would not sell his opinion for an expert witness's fee. His conclusions were dictated by the evidence. When the red arrows connecting similar notes were counted up, how could the songs be characterized as other than strikingly similar?57

The judge read the jury instructions and sequestered the jury at the end of the day. They deliberated for most of the next day, and at 3:30 p.m. returned a verdict for the plaintiff. "How Deep Is Your Love," they said, infringed Selle's song.

The jury decision did not finally resolve the matter. Judge Leighton nullified the jury verdict, granting the defense motion for a judgment notwithstanding the verdict (j.n.o.v). The judge's written opinion explains his reasons. A judgment notwithstanding the verdict is nothing more than a directed verdict granted after the jury has brought in its verdict.58 To satisfy the criteria for a j.n.o.v. the judge must view all evidence in the light most favorable to the nonmoving party, here the plaintiff. The judge must find that, even with all justifiable inferences, the evidence simply cannot support the jury's decision.59 It is immaterial that at the close of evidence the court, knowing no more then than now, denied the motion for a directed verdict and sent the case to the jury.60

The judge explained that the plaintiff never rebutted defendants' evidence of independent creation, the testimony of witnesses present at the composition of "How Deep Is Your Love" buttressed by the recording of the composition process. Although an inference of copying might be justified had plaintiff shown striking similarities, that inference here would be at war with the undisputed testimony of independent creation. Inference alone cannot outweigh actual testimony; therefore, the inference could not stand. The result was that some evidence of independent creation, albeit weak, for the defendants trumped no evidence to support the plaintiff's claim. Without at least an inference of copying, there can be no copyright claim regardless of the similarities. Thus, the verdict could not stand as a matter of law.61

Selle appealed, claiming the district court misunderstood his theory of proof.62 The United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit began its analysis by stating that copying must be proved. Although direct evidence of copying is often lacking, circumstantial evidence of access and substantial similarities are sufficient. Where there is no evidence of access, striking similarities may raise a permissible inference of copying by showing that independent creation, coincidence, or common source are, as a practical matter, precluded.63 Striking similarity per se, however, does not suffice. It provides only one piece of circumstantial evidence tending to show access. It must be viewed with other evidence. For example, if the plaintiff admitted to keeping his work under lock and key, striking similarity could not allow the jury to infer access.64

In this case, the evidence was inadequate to show that the Bee Gees had access to Selle's song.65 Evidence of access must extend beyond mere speculation.66 Plaintiff relied on Parsons, who ruled out independent creation but did not state that the similarities could result only from copying.67 Parsons had not addressed the possibility of a prior common source. Although the burden of showing a common source normally rests with the defendant, a plaintiff attempting to show striking similarity must bear the burden of showing no prior common source.68

The Court of Appeals affirmed Judge Leighton's judgment. Parsons had shown striking similarities in a nonlegal sense only. Plaintiff had failed to provide a sufficient basis for the jury to infer that the Bee Gees had access to Selle's song.69 Those not familiar with the law may find this result remarkable, but part of the trial judge's role is to guard against excesses of the jury. Here, the jury apparently believed that similarities alone could support an infringement claim. They cannot. No evidence had been put before them that the Bee Gees could have had access to Selle's song or that the similarities were so striking that they could result only from copying. The final outcome did not rest on a legal technicality. Rather, the missing evidence addresses the core of substantive copyright law, which holds that copyright does not grant a monopoly on particular expression; it protects the author only against copying. Plaintiff had not met his burden of proof. One can only speculate as to why Judge Leighton allowed the question to go to the jury rather than granting a directed verdict at the close of evidence.

Current Approaches to Expert Testimony

The Selle case was a landmark ruling on the doctrine of striking similarities, and it has been the subject of much legal writing. It is easy to criticize Parsons's testimony as legally inadequate, a fault probably attributable to the attorney who failed to prepare him. But Parsons's analysis is also musically inadequate. Unfortunately, it is typical of what one finds in plagiarism cases and might even be characterized as conventional. (Of course, some expert witnesses do competent work, and criticism here is directed towards predominant but not universal practices.) Parsons can be faulted for taking a myopic view toward his task. He did not gather sufficient musical evidence to support his conclusions. Perhaps he did not understand his role sufficiently, and this too reflects poorly on the lawyer who called him to the stand without adequate preparation.

The expert witness has a responsibility to know his craft. Assuming that Parsons was a competent theorist, it is difficult to understand why he did not bring the full weight of his knowledge to bear on his analysis. He chose instead to present a facile and superficial account of similarities. His testimony is typical of plagiarism analyses in its reliance on counting identical notes. Because the outcome at trial will be determined by people without musical training, it is tempting to base the analysis on statistics rather than music theory. Lay jurors will find statistics an appealing substitute for aesthetics and music analysis. No doubt, the real difficulties of explaining theoretical principles to the uninitiated drive many experts to simplify their analyses, but they should not jettison their craft entirely. An expert can tailor his presentation of the evidence to suit the jury's level of understanding without basing his analysis on false principles. Yet typically, experts exclude essential musical factors from their analyses wholesale. They rarely discuss tonal function, or indeed any musical function, and consequently all musical events tend to be set out chronologically and accorded equal weight. Further, musical parameters are simplistically defined for the jury. For example, experts often define melody merely as a succession of pitches. This, of course, ignores all nonadjacent relationships, which is another common failing of courtroom analyses, and misleads the jury concerning very fundamental musical principles.

These predominant approaches to proving substantial similarities lead to the same unacceptable result: the analysis has the effect of replacing the listening process. In many cases, one can only conclude that this was the affirmative intent of the party presenting the analysis. But the only permissible purpose of an expert witness is to help the trier of fact. In a music plagiarism case, the trier of fact must judge musical similarities, which necessarily exist in sound and not on the printed page. Therefore, any analysis that does not help the trier of fact to listen should not be admitted under the rules of evidence. The fact that some percentage of notes corresponds is misleading. Its relevance is substantially outweighed by its prejudicial effect, and the judge should disallow such testimony.70 Unfortunately, a judge does not know that this kind of note counting will not pass for serious analysis among music theorists. The judge infers, because neither side says otherwise, that this is what music theorists do.

Here, musicians are at fault. The profession generally is not aware of what passes for music theory in court. Yet purported music experts have presented this superficial note counting in lieu of analysis since the reported cases began describing music expert testimony. The courts have rightly concluded that this form of analysis, the only form known to the judiciary, has nothing to do with how music sounds and that it constitutes unreliable proof of copying. Of course, the court understands the problem only partially. Like many critics of music theory, the court seems to perceive listening and analysis as two unrelated activities. The court's only exposure to music theory, the testimony of experts, supports this perception. The court has drawn from this evidence the inevitable conclusion that theorists discover those aspects of music that cannot be heard and that lay people can adequately discern all audible aspects of music. Perhaps reflecting this belief, the court has established the "ordinary listener" test in part to deal with perceived inadequacies of music theory. Under this test, experts may analyze the music to show the existence or nonexistence of copying, but they are precluded from testifying on the ultimate issue of misappropriation—whether the offending work has stolen the essence of the copied work. Instead, the jury assumes the role of "the reasonable person," as it does in many areas of law, to determine whether the copying is sufficiently serious to warrant legal remedies. By excluding expert testimony on this issue, the court ensures that these ordinary listeners do not have their aesthetic perceptions tainted by intellectual concerns, and that they reach their ultimate conclusion based on the music and not on the analysis. Indeed, on the ultimate issue, the court admonishes jurors to listen as they normally would, with untutored ears. Although the court's concerns may be grounded on a flawed understanding of music analysis, it has wisely devised ultimate tests of infringement that require jurors simply to listen, thus blunting the impact of an analysis that fails to account for how music is heard.

Why have experts favored note counting that masquerades as analysis when such superficial techniques can be readily rebutted by competent musicians? Perhaps it remains the analytical method of choice in court because it cannot be readily attacked by lawyers. Presently, writings on music plagiarism support a highly circumscribed view of music. Much of the misinformation can be traced to a legal treatise on music copyright by Alfred Shafter written in the 1930s.71 Shafter apparently had no musical training, evidenced by his thesis that music has only thirteen [sic] notes and that all pleasing combinations of these notes have long since been exhausted. He argued essentially, although not explicitly, that music is an inexpressive art with a stunted vocabulary. In Shafter's view, composers must inevitably engage in plagiarism and then devise clever ways to disguise their thefts. Shafter's treatise is replete with references to cunning plagiarists:

Clever infringers attempt to deceive composers by alterations and changes in their musical ideas, these disguises taking form, as the English Act says, of "colourable imitations." Colorable is another word for "camouflaged"; and a musical idea so treated is just as much an infringement as one taken openly. The difficulty of proving the theft does not lessen the liability of the thief. . . .

Much has been made of the fact that Brahms took the melody of the Westminster Chimes as the theme for his famous horn motif in his First Symphony. . . .

Olin Downes says that what Brahms changed is not the notes, but their rhythm. In the case of a copyrighted composition this change might be the colorable variation mentioned; but in the instance of music in the common domain, the copy is permissible. What is important in this respect is the fact that one may copy a melody by changing the rhythm—and still be infringing.72

Sigmund Spaeth provided another strong influence on the methodology of expert testimony. At about the same time as Shafter and in much the same vein, Spaeth dubbed himself the "tune detective" and performed music analysis for audiences as a kind of vaudeville stunt. He found plagiarism rampant. Spaeth appeared frequently as an expert witness in the 1930s, 40s, and 50s, and his brand of analysis seems to have set the standard for succeeding generations of experts.73

Shafter, and apparently Spaeth, believed that the value of experts lay in their ability to ferret out the devious ways in which composers disguised their thefts.74 Never mind the ordinary listener, who may be fooled by the fact that defendant's work sounds different than plaintiff's. This school of commentators seems to find composers at once too lazy to be original and yet masters of creative deception.75 Music to them is not only an inexpressive art, but a devious one as well. Schenker, responding to earlier advocates of such views, railed against this naïve approach to music:

It can only be regarded as a ridiculous attempt at debasement and disparagement of the diminutions of the masters when a certain literature busies itself with finding "wandering melodies" in the foreground, maintaining that similarities exist where they do not, with drawing lines of historical connection in every direction, where none in fact exist, or with pointing out plagiarisms where none are to be found. The employment of comparable superficial methods in language and literature would call forth general laughter and head-shaking over the deplorable intellectual state of any such writers and teachers.76

Whatever credence one gives to Schenker's unapologetic opinions, he is surely correct in this instance insofar as it has relevance to the law. Shafter's theory of music does not comport with the experiences of listeners, regardless of their taste or training in music, and should be discarded on that ground alone. The public conspicuously disavows the notion that musical expression has been exhausted most every time it purchases a new recording. A more astute legal commentator recently took aim at those who delight in discovering rampant plagiarism:

These self-styled music critics seem to envision a world full of composers endeavoring mightily to conceal acts of plagiarism, even going so far as to change all the notes.77

Shafter's unfortunate treatise and works perpetuating his views continue to thrive in legal scholarship because of the absence of scholarly criticism. Musicians have not bothered to rebut Shafter, probably because they either have not read his treatise or have not considered it worthy of comment. But the simplicity of Shafter's misconceptions appeals to litigants, many of whom have no motivation to prove Shafter wrong. The litigants' only goal, quite understandably, is to win the trial. The pressure, then, is for the expert witness to omit the difficult and more relevant aspects of analysis, to emphasize "notes," and to quantify the shared vocabulary of "notes." The jury will grasp this watered-down analysis, and the judge will admit it into evidence. In these circumstances, there seems little incentive to do more.

Musicians have a large stake in elevating this process. Any composer, whether cast as plaintiff or defendant, potentially faces unfounded claims or defenses, based on this pseudo analysis, that could divest him of his property rights. It is up to the music profession to develop accepted guidelines of forensic analysis so that competent expert witnesses can defend their methodologies and so that judges can distinguish the theorist from the charlatan.

Guidelines for Forensic Analysis

It lies beyond the scope of this article to set out a full regimen for the forensic analysis of plagiarism. That task has been undertaken elsewhere.78 But this discussion must at least set forth reasonable indicia of a competent forensic analysis, more for the benefit of the court and parties who seek to introduce such evidence than for music analysts, who may be presumed to understand the necessity of the approach set forth here. The criteria are derived primarily on musical grounds, but certain aspects of law argue for the inclusion of some techniques and a very cautious approach to others.

As a general proposition, analysis that explains the processes of composition and perception should be considered legally relevant while anecdotal and purely statistical data should not. The court should be presented with an analysis that employs a variety of analytical techniques, each confirming the others. An analyst who uses only one method of comparison presents a one-dimensional account of the music and might easily create a false impression for the trier of fact. Of course, some comparisons will yield more information than others, depending on the nature of the works analyzed. In a non-adversarial setting, opposing experts might agree on which methods would provide the greatest insight, but in court, agreements on such fundamental issues are rare. The plaintiff points out similarities and the defendant stresses dissimilarities. Each chooses the comparisons that argue best for his or her position; each tends to present half of the picture. This is how the American judicial system works, and it would be pointless to argue here that the system should be changed. Music theory can function well within the current framework, provided that the trier of fact sees the whole picture. The system tends to fail when both sides present less than half or when one side presents something that does not belong in the picture. As the situation now stands, the court does not know what the total picture looks like. It can neither rule out extraneous evidence nor criticize an incomplete presentation.

A valid forensic analysis should begin with a thorough, discrete analysis of each work at issue without any attempt to compare the two. This requirement is fundamental. Music is comprised of relationships, and in order to understand the relationships, each aspect of the music must be examined in the context of the work in which it appears. Analysis necessarily entails segmentations and reductions. The process of segmentation and reduction provides the greatest opportunity to skew the analysis in the direction of the desired result, and improper segmentation supports some of the most egregious examples of poor courtroom analysis. Segmentations of each work, therefore, should be made with reference to criteria dictated by that individual work. The analyst should attempt to compare only segments that have relevance within the work from which they are extracted. Where the analyst allows the criteria of one work to determine the segmentations of the other, the analysis will be based on false relationships and extra-musical criteria.

The analysis of each individual work should include a thorough delineation of that work's thematic vocabulary and formal structure. The expert should explore all functional relationships, including harmony and rhythm in isolation. Perhaps most critical, a hierarchical analysis of each work must be completed. The expert will find virtually no precedent for the admission of this evidence, and the lawyer seeking to introduce it can expect heated objections and a skeptical judge. But the law cries out for the information it presents. Among its many benefits, it separates idea from expression and originality from common musical function. When the judge comprehends the import of hierarchies in music, many of the problems outlined above will be near a solution. If a jury can be taught to hear middleground features, it will achieve the means to determine which similarities are substantial.

With a discrete analysis of each work in hand, the expert can begin the process of comparing one work to the other. Comparison will be limited to those segmentations and reductions already determined to be relevant. Traditionally though, experts have begun to compare works without prior analysis; they have confined their review to temporal comparisons of isolated phenomena and visual criteria, "where pitches and rhythms coincide," as Parsons testified. That process is haphazard and its results indefensible. Any child who has learned to read music can identify corresponding notes and connect them with arrows.

Assessing Similarities

A more comprehensive analytical approach should provide the means of separating meaningless correspondence of surface features from similarities with musical significance. Surface features will always contain coincidental similarities. If, in addition to sharing these surface features, two works assign the same function to those features, then the similarities begin to be perceptible. If the functional similarities also appear in similar context, episodic similarities may be apparent. Finally, if all of these similarities are strung together in a sustained and concerted fashion, then the lay listener may recognize the sounds of one work as derived from another.

Given the complex nature of music, similarities that lack complexity and depth should not earn the label "substantial."79 The law must look to the nature of the art it examines in these cases and determine legal significance based on musical significance. Music does not exist in a set of pitches or static values, and an analysis of similar notes does not reveal the important relationships that control perception. Musical perception is a complex process; it deserves to be considered an intelligent process rather than a purely reflexive one. The lay ear processes the same data and connects the same relationships as that of the expert, but the lay listener generally does not understand the nature of the process or possess the means to articulate the experience. The expert witness should illuminate the process of listening for the lay trier of fact, and jurors should be encouraged to combine, rather than separate, the power of their ears and minds.

The principal attribute of similarities that deserve to be considered substantial is that they should be perceptible simultaneously by the ear and mind.80Arnstein v. Porter established a bifurcated approach. The expert could provide opinion testimony on the issue of copying, and the jury would have to determine misappropriation based on their own untutored perceptions. Bifurcation of this process by the court may have served a useful, analytical purpose; but like all analytical segmentations, the sum of the segments does not provide a complete answer.81 The trier of fact must assimilate the data before making a final evaluation, but the courts' bifurcation has hindered assimilation. The law has not successfully combined parts into a meaningful whole.82

In addition to the general proviso that substantial similarities must be simultaneously perceptible to the ear and mind, three separate and specific guidelines for determining substantial similarity are suggested to guide the court and expert witnesses. In order to reach a conclusion that substantial similarities exist, the trier of fact should find all three of the following conditions to be met:

(1) Plaintiff should be required in a hierarchical analysis to show similarities in the middleground. Function and context can best be determined at this level. The middleground accounts for larger-scale and more distant relationships that control how musical details are heard. Middleground aspects also guide the discovery of greater abstractions than foreground materials. Music cannot be substantially similar in foreground features alone, because similarities confined to foreground features are likely to be the result of idiomatic figurations or pure coincidence.83 If only minor changes have been made to disguise an act of plagiarism, similarity of middleground will remain intact and support the plaintiff's argument.

(2) Plaintiff should be required to show similarities in the foreground. Because the middleground tends to reflect more abstract elements, similarities confined to the middleground may be unprotectable. Stylistic formulae, key relationships, rules of counterpoint and harmony, as well as other middleground aspects all possess a greater likelihood of similarity. The critical question for the trier of fact is whether the defendant realized, elaborated, or prolonged middleground similarities using the same foreground materials as the plaintiff. Only the foreground contains elements specific enough to corroborate middleground similarities and support a claim of infringement.

(3) Plaintiff should be required to show a nexus between specific foreground and middleground similarities. The random cumulation of disparate elements, some taken from foreground and some from middleground, does not suggest copying. Isolated and episodic similarities, no matter the quantity, do not support a claim of plagiarism any more than the use in prose of a similar vocabulary. Only the relationship between foreground and middleground similarities tends to show copying as opposed to coincidence. The nexus ties similarity of surface to similarity of function—the same means of expression employed to express the same thing.

Proof of striking similarities presents a particularly difficult problem. What degree of similarity disproves coincidence? Are any features of popular music so striking that their duplication could only be the result of copying? It seems that something more than an isolated figure or "common error" is needed for the expert to conclude, absent evidence of access, that the defendant copied. Rather, some quantity as well as quality of similarity must be present. The striking similarity doctrine poses great potential for abuse and it should be reserved for the most egregious takings. The expert should be reluctant to testify to striking similarities, particularly when dealing with popular music, without virtual and uninterrupted replication of a substantial portion of the work.

The Selle case illustrates the dangers inherent in the doctrine of striking similarities. Parsons went too far, drawing the conclusion of striking similarities on insufficient evidence, and could not adequately defend his position when faced with its implications on cross-examination. Of course he did not know with certainty whether the Bee Gees had copied Selle's song. Independent creation was not precluded. Although the songs exhibited real similarities, those similarities were not so striking that access could be inferred.

Conclusion

Music theorists called as expert witnesses must reexamine their role. To be helpful to the trier of fact they must teach the jury to listen to the music instead of scrutinizing the score for statistical anecdotes. In short, they should practice their craft first and worry about how to make it understandable second.

The judicial system that has abetted the problem will improve only when judges learn the nature of acceptable music analysis. Individual experts hired to advocate one party's position cannot assume the role of neutral educator to the court. The music profession as a whole should add to its agenda the discussion and further study of courtroom analyses, and it should speak to the court regarding the qualification of experts and the indicia of relevant testimony. The profession's adoption of standards for forensic analysis will place a powerful tool in the hands of the more worthy party. It will not guarantee accurate results, but it will help to expose the true plagiarist, facilitate reasonable settlements, and seriously impede the prosecution of frivolous claims.

This endeavor by the profession would also redound to its own benefit in many ways. Having original compositions protected by a rational application of law is the obvious, direct benefit. In addition, however, the development of music forensics opens new avenues of inquiry. Explaining music and analysis in the rigorous and critical legal environment can only enhance our own understanding and appreciation of what we as music theorists do. The expert witness's role is, in the end, a profound pedagogical challenge, and what we learn in presenting music to the jury, a very receptive but untrained audience, may teach us to communicate more precisely and effectively with each other.

1Selle v. Gibb, 567 F. Supp. 1173 (N.D. Ill. 1983), aff'd, 741 F.2d 896 (7th Cir. 1984).

2The judge sits as trier of fact when there is no jury. Parties will often demand juries in plagiarism cases, as was done in Selle, and for simplicity, this discussion will assume the trier of fact is a jury.

317 U.S.C. § 102(b).

417 U.S.C. § 107.

517 U.S.C. § 501(a).

6See Arnstein v. Porter, 154 F.2d 464 (2d Cir. 1946).

7Selle v. Gibb, 741 F.2d 896 (7th Cir. 1984). See generally, Sherman, Musical Copyright Infringement: The Requirement of Substantial Similarity, 22 Copyright L. Symp. (ASCAP) 81 (1977).

8154 F.2d 464, 473 (2d Cir. 1946).

9Record at 6-7.

10Record at 8.

11Record at 9.

12Record at 11.

13Record at 10.

14Record at 12.

15Record at 21-36.

16Record at 109-12.

17Record at 116-17.

18Record at 187-89.

19Record at 198.

20Record at 199.

21Record at 202.

22Record at 222-23.

23Record at 224-30.

24Record at 232.

25Record at 232-37.

26Record at 243-48.

27Record at 249.

28Record at 249.

29Record at 249-50.

30Record at 254-62.

31Record at 266.

32Record at 267-70.

33Record at 266-67.

34Record at 278.

35Record at 279. Parsons sought cover with this answer again when asked why he didn't check to see if the similar rhythm might be duplicated by other songs. Without that knowledge, how could he know if the rhythmic similarities were significant? Parsons replied, "My assignment was to compare these two songs in question and that is what I did." Record at 309. The tendency to defend oneself during cross-examination is understandable, but the effect of this answer is to transfer blame to the party on whose behalf the witness is testifying.

36Record at 355.

37Record at 286-88.

38Record at 818.

39Stipulations are agreements between counsel concerning facts incidental to the proceedings or not controverted, such as, here, the identity of the taped excerpt. Lawyers are not supposed to waste the court's time by requiring proof of uncontroverted facts. A stipulation read into the record comprises part of the evidence.

40See, e.g., "Lawyers Play 'Name That Tune' in the Bee Gees Case," Variety, 23 February 1983, 2; United Press International (Domestic News), 17 February 1983. The excerpt was taken from Theme B of "Let It End."

41Record at 410.

42Record at 414ff.

43Record at 571.

44Record at 573.

45"Cross-examination should be limited to the subject matter of the direct examination and matters affecting the credibility of the witness. The court may, in the exercise of discretion, permit inquiry into additional matters as if on direct examination." Fed. R. Evid. 611(b).

46Record at 620.

47Record at 621-22.

48Record at 621-23.

49Robert C. Osterberg, interview by author, 26 October 1990, New York.

50The judge may direct a verdict, rather than submitting the issue to the jury, where there is no material issue of fact and one party is entitled to judgment as a matter of law.

51Record at 637-39.

52Record at 959-60.

53Record at 960-62.

54Record at 963 and 966.

55Record at 977.

56Record at 973.

57Record at 1039-47.

58Selle v. Gibb, 567 F. Supp. 1173, 1179 (N.D. Ill. 1983), aff'd, 741 F.2d 896, (7th Cir. 1984).

59567 F. Supp. at 1179.

60Id.

61Id. at 1182-83.

62Selle v. Gibb, 741 F.2d 896, 900 (7th Cir. 1984).

63Id. at 901.

64Id.

65Id. at 902.

66See Ferguson v. National Broadcasting Co., 584 F.2d 111, 113 (5th Cir. 1978) (Access must be more than a bare possibility and may not be inferred through speculation or conjecture.)

67741 F.2d at 905.

68Id.

69Id.

70See Fed. R. Evid. 403.

71Alfred M. Shafter, Musical Copyright, 2d ed. (Chicago: Callaghan, 1939).

72Id., at 193-99 (emphasis in original). See also, Orth, The Use of Expert Witnesses in Musical Infringement Cases, 16 U. Pitt. L. Rev. 232 (1955). "The propensity has existed for a long time to steal the tunes of other composers. Liszt made free use of gypsy melodies and Handel was a notorious plagiarizer. Upon listening to Brahms' First Symphony, for instance, one might well recognize that the broad chorale of the fourth movement has been transplanted from the 'Ode to Joy' motif in Beethoven's Ninth Symphony, which, in turn, had its origin in the minuetto of Mozart's Haffner Symphony, which came from Sandrina's aria 'Una voce vento al core.'" Id. (citing Shafter, Musical Copyright, and Fox, Evidence of Plagiarism in the Law of Copyright, 6 U. of Toronto L.J. 414, 415 (1946)).

73The attorney Louis Nizer, in his book My Life in Court (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1961), describes his cross-examination of Spaeth in the plagiarism trial involving "Rum and Coco-Cola," Baron v. Leo Feist, Inc., 78 F. Supp. 686 (S.D.N.Y. 1948), aff'd, 173 F.2d 288 (2d Cir. 1949).

74Shafter, Musical Copyright, 189.

75"If it were not for the fact that juries are almost never called in [popular music cases], the average ear test would be somewhat ineffective in holding copiers for infringement, because infringing tunes are usually written—probably with success—to deceive this very class of listener. Thus the infringer, who had cleverly disguised the tune by rhythmic and/or harmonic tricks, would be given great leeway, amounting in the case of a skillful and careful job of plagiarism to virtual immunity." Orth, Expert Witnesses, 236.

76Heinrich Schenker, Free Composition, trans. and ed. Ernst Oster (New York: Longman, 1979), 105.

77Keyt, An Improved Framework for Music Plagiarism Litigation, 76 Calif. L. Rev. 421, 424 n.17 (1988). "We are dealing, of course, with a romantic concept still widely shared by laymen: the composer creates in an intoxicated daze, at 'white heat,' and if he uses material of earlier creation, he is a plagiarist, a swindler, and a thief. One wonders why the other romantic conception of the artist as an irresponsible individual who must not be measured by the standards of bourgeois ethics is not applied in this instance. . . . Only those who do not understand the process of musical composition, who cannot see and feel the subtlety of transfiguration that can be created by a changed melody, even a single note, rhythm, or accent, have made a moral issue of something that is a purely esthetic matter." Id. at 425 (quoting Paul Henry Lang, George Frederic Handel (1966), at 559-69).

78M. Fletcher Reynolds, Music Analysis for Expert Testimony in Copyright Infringement Litigation (Ph.D. Dissertation: University of Kansas, 1991).

79This runs counter to Orth's proposition: "While the rule is that numerous similarities will create an inference of copying sufficient to show infringement if this circumstantial evidence is convincing, it has been held that this rule is not applicable where the claimed similarities in the two works are so technical or complex that the average person is unable to hear any substantial similarity. . . ." Orth, Expert Witnesses, 238 (citing Gingg v. Twentieth Century Fox Film Corp., 56 F. Supp. 701 (S.D. Cal. 1944)). In fact Gingg refers only to similarities that are "highly technical in nature." Orth apparently added the term "complexity." Where similarities share a greater complexity of relationships, they should be more apparent to the average listener, not less.

80Although the author disagrees with many of Orth's premises, Orth reaches a similar conclusion regarding the combination of ear and intellect. "Expert testimony would be used to guide the jury, to point out significant similarities and possibly to explain and clarify psychological reactions to the two compositions. . . . Such testimony would be heard along with the impression made on the jury's ears by several careful playings, and, taking the whole testimony and complex of impressions together, the decision would be left to the jurymen, under appropriate summary and instructions by the judge. Included should be an instruction to the effect that the jury must, in whatever state of enlightenment the experts have developed in it, now hear substantial similarities between the works before holding defendant liable.

"This is not the approach Judge Frank [in Arnstein v. Porter] advocated for use with a jury. It contains no compartmentalizing of expert testimony and then putting it aside when the final determination of illegal copying is made. It is instead that relevant expert analysis and opinion is part of all the evidence receivable, and that the issue of infringement of popular music is then decided by a possibly enlightened consensus of lay ears." Orth, Expert Witnesses, 255-56 (emphasis in original).

81Judge Clark's dissent in Arnstein v. Porter points out the potential problem. "I find nowhere any suggestion of two steps in the adjudication of this issue, one of finding copying which may be approached with musical intelligence and the assistance of experts, and another that of illicit copying which must be approached with complete ignorance; nor do I see how rationally there can be any such difference, even if a jury—the now chosen instrument of musical detection—could be expected to separate those issues and the evidence accordingly." 154 F.2d 464, 476 (2d Cir. 1946).

82The bifurcation was intended to limit expert testimony, but Fed. R. Evid. 704, abolishing the ultimate issue rule, provides an adequate basis for allowing expert testimony on all infringement tests. Der Manuelian, The Role of the Expert Witness in Music Copyright Infringement Cases, 57 Fordham L. Rev. 127, 147-48 (1988).

83"Preservation of context must be a crucial element of copying. It is not enough to compare only strings of acoustical events. The comparison must include the structures that the sounds articulate." Keyt, Improved Framework, 437 (emphasis in original).