Two distinct categories of harmonic behavior can be discerned in The Rite of Spring. One operates on the principle of pedal point or sustained core harmony combined with ostinato. Virtually all the internal sections—that is, those enclosed by the Introduction of Part I and Danse sacrale of Part II—use this approach of asserting tonality by simply stressing a keynote. The other principle, employed in these two outer sections and ultimately used to determine the global succession of pedal tone centers during the course of the work, involves various and sophisticated manipulations of traditional functional progression grounded in circle-of-fifths and major-minor related key hierarchies. Stravinsky's cultivation of this second type of harmonic movement has been little discussed. With this analysis, I propose to examine it.

Stravinsky's tonal practice in the Rite draws upon four techniques easily classifiable: (1) the use of a standard tonic-subdominant-dominant (or "functional") chord progression, which includes also the exploration of chord prolongation and chord substitution, especially at the tritone; (2) bifocal statement of material first in the minor and then in the relative major; (3) the fusion or crushing together of principal harmonic functions within a key; (4) and the application of large-scale tonal progression to the relationship between the first and second parts of the work, and to the succession of static pitch centers from section to section throughout.

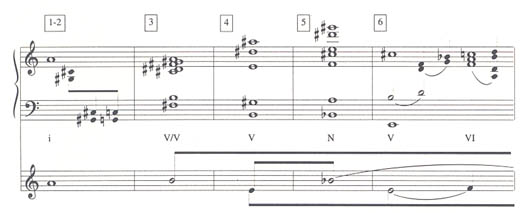

Example 1 presents a reduction of the fundamental harmonic progression that shapes the introductory passage from rehearsal number 1 through rehearsal number 10.1 Changes in harmony correspond for the most part to the rehearsal number indications, and at each turn new motivic material enters and new textures are created. Though the profusion of motives and complexity of orchestral texturing disguise it, and though chords are often stated in an inversion that places the fifth in the bass, thereby obscuring immediate recognition, each subsection, as demarcated by rehearsal numbers, orients itself around a distinguishable triadic form. Further, when these structures are distilled as shown in the schematic here, and viewed in succession, it becomes clear that they are organized within or comprise a most traditional, goal-directed phrase formula. From 1 to 10 the music moves, in the key of a, i-V. Within this stretch, Stravinsky touches upon V two times, at 4 and 6. Except for the move in the center of the segment toward a chord built on C (a modified III, suggesting an excursion to the relative key) at 7, all other chord changes point toward the iv family—V/V, VI (a subdominant element as it compares with the iv6 of the Phrygian cadence), Neapolitan, IV and so on. One concludes that the essential harmonic motion occurs in the first three rehearsal sections, going from i to V/V landing on V. Everything after that point serves to prolong the arrival on V, by shifting to subdominant functions—chords preparatory to the V—or the relative key center.

Example 1

Example 1 is in three levels. The first shows the basic pitch material used in each section. Black notes are more ornamental in the music than white notes. Triadic form readily emerges from the aggregate in any measure. The middle level identifies the triadic structures by Roman numeral functions in the key of a minor. The process of paring away added tones to reveal clear triadic structure is akin to Hugo Leichtentritt's analytical method for Schoenberg's Op. 11, in which he shows how traditional chords and chord formulas have been transfigured by enriching the chromatic content (see Musical Form, Cambridge, 1951). On the bottom level, the triad roots are arranged to show motion by fifths. Beams group together the subdominant versus dominant events, and illustrate prolongation of chord functions. Any resemblance of this to a Schenkerian graph is purely incidental, though it may not be inappropriate to apply concepts of Schenker analysis to this music.

The prolongation technique is applied much in the same manner as in many classical and romantic development sections. The peculiar practice of substituting for V the chord a tritone away (the Neapolitan, or some enriched form of it) is relied upon twice here by Stravinsky. To assist in showing more clearly the basic tonal chord progression underlying this passage, the lowermost staff on the schematic extracts from the triadic forms above the corresponding chord roots. Observing this succession, movement by fifths can be even more readily perceived, and, by adding beams and ties, the prolongational effect can be more easily understood. Further, certain symmetries, especially in relation to tritone groupings, become apparent, testifying to the authority and high degree of conceptualized order the composer has brought to bear upon the harmonic structure of the Introduction.

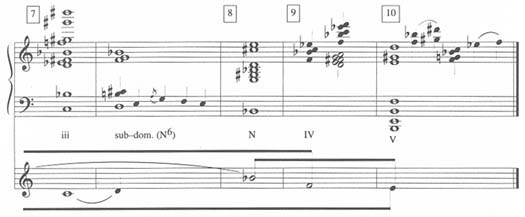

In like fashion, Stravinsky rivets the Danse sacrale upon solid tonal underpinnings. Many have thought there to be a d tonic for this section.2 The deliberate structural emphasis on subdominant and dominant areas, in addition to the primitivistic repetition and recurrence of the pitch class d, confirm this. At a finer level of detail, no question can arise concerning the functional orientation of the Danse. Example 2, again in sketchbook style, telescopes the chordal movement from rehearsal 149 to the end.

Example 2

The passage from 149 through 153 sits upon a g rooted chord—a iv13/9/7, if we analyze in d minor, with the third omitted (the major-minor third  /

/ is taken up melodically with the famous trombone quintuplet motif). This harmony makes a plagal resolution to i—with added sixth and ninth—at rehearsal 154, the tonic lasting, despite some neighboring motions, through 156. Contrasting colors are placed through 157 and 158, to return again on the tonic at 159 through 161. The next primary chord change takes place at 162. Here the music rests upon an f-based harmony, suggesting a move to the relative major area. Flowing toward the recurrence of principal material at 167, chords related to the previous contrasting passage, 157 and 158, appear at the bridge phrase, 165 through 166. Although the bridge involves a chromatic departure from the

is taken up melodically with the famous trombone quintuplet motif). This harmony makes a plagal resolution to i—with added sixth and ninth—at rehearsal 154, the tonic lasting, despite some neighboring motions, through 156. Contrasting colors are placed through 157 and 158, to return again on the tonic at 159 through 161. The next primary chord change takes place at 162. Here the music rests upon an f-based harmony, suggesting a move to the relative major area. Flowing toward the recurrence of principal material at 167, chords related to the previous contrasting passage, 157 and 158, appear at the bridge phrase, 165 through 166. Although the bridge involves a chromatic departure from the  ("relative major") material in 162 through 164, it nonetheless culminates at the end of 166 on a

("relative major") material in 162 through 164, it nonetheless culminates at the end of 166 on a  rooted chord of ironically brief duration which, for practical purposes, can be regarded as c, or V of the relative major. Following the recapitulation of principal material, the music traces a VI-ii°-V-i progression in rehearsal segments 173, 174, 186 and the final bar (respectively). My overview thus far explains the goal-directed, functional harmonic working of the Danse, but fails to mention the false recapitulation of the initial material at 167—that is, at the half step lower—or the opening statement of that material at 142 through 148. I will take these segments up now, and ultimately relate them to the d minor/F major tonal scheme already unveiled.

rooted chord of ironically brief duration which, for practical purposes, can be regarded as c, or V of the relative major. Following the recapitulation of principal material, the music traces a VI-ii°-V-i progression in rehearsal segments 173, 174, 186 and the final bar (respectively). My overview thus far explains the goal-directed, functional harmonic working of the Danse, but fails to mention the false recapitulation of the initial material at 167—that is, at the half step lower—or the opening statement of that material at 142 through 148. I will take these segments up now, and ultimately relate them to the d minor/F major tonal scheme already unveiled.

The theme at 142 takes d as its central tone. However, ambiguity surrounds the identity of this tone as a true tonic. Undermined by a strong  in the bass, and heard in conjunction with

in the bass, and heard in conjunction with  and other chromatic tones foreign to d minor, it seems to relate locally more as a dominant to g, or iv, than to d minor as tonic. Understood in this way, the characteristic Danse chord (Example 3), of which pitch class D is the prominent member, can be separated into two components: it contains pitches of the V/iv (that is, a dominant seventh based on d), and tones of the augmented German sixth of iv.

and other chromatic tones foreign to d minor, it seems to relate locally more as a dominant to g, or iv, than to d minor as tonic. Understood in this way, the characteristic Danse chord (Example 3), of which pitch class D is the prominent member, can be separated into two components: it contains pitches of the V/iv (that is, a dominant seventh based on d), and tones of the augmented German sixth of iv.

Example 3

The derivation of such a structure involves the crushing together or fusing of two recognizable and distinct harmonic functions within the key of iv, namely, dominant and subdominant. The idea of fusion is introduced early in the Rite. For example, the hallmark staccato chords at 13, The Augers of Spring, superimpose an  dominant seventh chord and an

dominant seventh chord and an  major chord. In another way of thinking, they crush together into a single simultaneity all the tones of the a minor scale in its harmonic minor form (Example 4).

major chord. In another way of thinking, they crush together into a single simultaneity all the tones of the a minor scale in its harmonic minor form (Example 4).

Example 4

Stravinsky's fusion of the g minor V7 and the German augmented sixth at the beginning of the Danse sacrale represents a more complex expression of the same principle. I do not wish to leave these opening measures at rehearsal 142 too hastily, otherwise their harmonic logic and richness would go unappreciated.

The composer has chosen the chords in the last bar of 142 with great care. The first, tied over from the previous bar, we have already identified. The remaining three, shown in Example 5a (top brace), restate in different arrangements the same harmonic aggregation as the first.

Example 5a

The second chord is built of a C dominant seventh and holds over the  and

and  from the first beat. The third chord contains the V7 of

from the first beat. The third chord contains the V7 of  minor and augmented sixth elements of that key. And the last chord is identical to the first—V7 of g plus augmented sixth elements—in pitch content, with the notes distributed somewhat differently. Though these chords are quite similar in nature, each subtly individualizes itself from the others. The second chord, if it were to agree strictly with the interval content of the others, would not tie over

minor and augmented sixth elements of that key. And the last chord is identical to the first—V7 of g plus augmented sixth elements—in pitch content, with the notes distributed somewhat differently. Though these chords are quite similar in nature, each subtly individualizes itself from the others. The second chord, if it were to agree strictly with the interval content of the others, would not tie over  and

and  but instead use

but instead use  (or

(or  ) and

) and  , to supply the appropriate augmented sixth element of the key of f to which the C 7 chord refers as dominant. Avoidance of strict adherence lends a certain tension to the movement, a feeling of the harmony struggling to pull away from its starting point. This sets up the strong arrival on the third chord, which does agree with the construct, but transposes the pitch level of the initial chord down a half-step, supplying a sense of freshness. (This transposition sets the precedent for the later "false recapitulation" at the half-step down at 167.) The fourth chord resolves the two previous ones by returning to the pitches of the first; however, it groups them in an alternate voicing so as not to rob the first of its special identity. Add to this the notion that, as we deal with three distinct chords—call them x, y, z—they stand as a surrogate for the formula I, IV and V, and one realizes that goal-directed hearing even guides the choice of virtual "cluster" sonorities. Finally, it is revealing to observe that the dominant seventh components of the second, third and fourth chords, move up in semi-tonal succession (Example 5b, lower brace): C 7,

, to supply the appropriate augmented sixth element of the key of f to which the C 7 chord refers as dominant. Avoidance of strict adherence lends a certain tension to the movement, a feeling of the harmony struggling to pull away from its starting point. This sets up the strong arrival on the third chord, which does agree with the construct, but transposes the pitch level of the initial chord down a half-step, supplying a sense of freshness. (This transposition sets the precedent for the later "false recapitulation" at the half-step down at 167.) The fourth chord resolves the two previous ones by returning to the pitches of the first; however, it groups them in an alternate voicing so as not to rob the first of its special identity. Add to this the notion that, as we deal with three distinct chords—call them x, y, z—they stand as a surrogate for the formula I, IV and V, and one realizes that goal-directed hearing even guides the choice of virtual "cluster" sonorities. Finally, it is revealing to observe that the dominant seventh components of the second, third and fourth chords, move up in semi-tonal succession (Example 5b, lower brace): C 7,  7, D 7.

7, D 7.

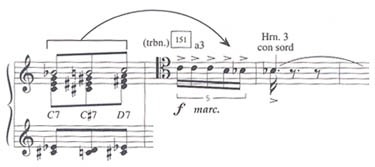

Example 5b

Spelling them in root form highlights the notes  ,

,  , and c on top, a melodic cell shown in white notes in the example. These notes at rehearsal 151 become transfigured into the well remembered trombone quintuplet motto previously cited (Ex. 5b).

, and c on top, a melodic cell shown in white notes in the example. These notes at rehearsal 151 become transfigured into the well remembered trombone quintuplet motto previously cited (Ex. 5b).

My discourse has inevitably taken a tangent, and I want to pull it back toward the central argument by looking now at the tonal attitude toward phrase construction in the opening theme of the Danse (142-148). Then I will proceed to the recurrence of this theme at 167 and venture an interpretation for Stravinsky's opting to state it at the alternate pitch center he has chosen. Earlier I spent some effort to break the Danse chord—the first four bars of 142—into two components, subdominant in the form of the German sixth and dominant in the form of the V7. This particular color characterizes the entire—what I will now call—antecedent phrase of the theme, and may be described as a chromatic expression of the IV-V fusion, owing to the semi-tonal adjustment made upon the fourth-scale degree. For the consequent portion of the phrase—measure 144 through the first two bars of 145—the music moves from an implied g minor to its relative,  major. Where in the antecedent the central function was V7 of g, in the consequent it becomes V of the

major. Where in the antecedent the central function was V7 of g, in the consequent it becomes V of the  , the relative major; the pitch f is strong in the outer parts. (Save for the abortive

, the relative major; the pitch f is strong in the outer parts. (Save for the abortive  at the end of their figure, the horns map out the descending

at the end of their figure, the horns map out the descending  major pentachord 5-4-3-2-[1, implied] two times in this passage.) Enriching the parallel between the two phrases, the consequent answers the chromatic combination of subdominant and dominant chord functions used in the antecedent with a diatonic realization of the basic paradigm. Namely, at the outset of 144, the plain iv6 of

major pentachord 5-4-3-2-[1, implied] two times in this passage.) Enriching the parallel between the two phrases, the consequent answers the chromatic combination of subdominant and dominant chord functions used in the antecedent with a diatonic realization of the basic paradigm. Namely, at the outset of 144, the plain iv6 of  is crushed together with notes of the V, an ingenious maneuver that keeps consistent the concept while varying the color.

is crushed together with notes of the V, an ingenious maneuver that keeps consistent the concept while varying the color.

The opening material of the Danse sacrale recapitulates "falsely" at 167 a semi-tone lower than its original statement. To this problem several observations can be addressed. First, Stravinsky noticeably predicts this structural event in the movement of harmonies selected for the initial measures of the Danse at segment 142 his D 7 + German augmented sixth chord of the first four bars shifts down a half-step on the second beat of the fifth bar to  7 + [

7 + [ -minor] German augmented sixth elements. He supports the choice contextually. The passage from measures 162 through 166 is bracketed by—at the beginning—an f-based harmony, and—at the end—a c-rooted harmony (written as

-minor] German augmented sixth elements. He supports the choice contextually. The passage from measures 162 through 166 is bracketed by—at the beginning—an f-based harmony, and—at the end—a c-rooted harmony (written as  , but enharmonic spelling does not necessarily hold importance), or, in functional terms, a I-V progression in F major. Crossing the bar into 167 the modified V function goes to the

, but enharmonic spelling does not necessarily hold importance), or, in functional terms, a I-V progression in F major. Crossing the bar into 167 the modified V function goes to the  (

( ) oriented transposition of the "fusion chord," substituting it in the manner of a borrowed sub-mediant for any return to I. The phrase connection, in other words, formulates itself using the model of the traditional deceptive cadence. Admittedly, this shies away from sufficiently explaining the

) oriented transposition of the "fusion chord," substituting it in the manner of a borrowed sub-mediant for any return to I. The phrase connection, in other words, formulates itself using the model of the traditional deceptive cadence. Admittedly, this shies away from sufficiently explaining the  level—or lowered sixth scale degree—for a deceptive cadence could be accomplished using the major sixth degree—

level—or lowered sixth scale degree—for a deceptive cadence could be accomplished using the major sixth degree— , the original pitch level—equally well. Only examination of the transitional passage in chromatic harmony of 165-166 , and its earlier correlative form 157-158 can afford a full understanding.

, the original pitch level—equally well. Only examination of the transitional passage in chromatic harmony of 165-166 , and its earlier correlative form 157-158 can afford a full understanding.

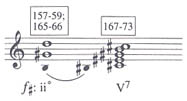

I have asserted that at the outset the fusion chord gravitates upon a V7 of g minor. Therefore, when the recapitulation at the lower semi-tone occurs, one must speak of the chord in terms of a V7 of  minor (despite the spelling). How is the V7/

minor (despite the spelling). How is the V7/ prepared? Functionally, dominant is prepared by subdominant, so some form of the subdominant of

prepared? Functionally, dominant is prepared by subdominant, so some form of the subdominant of  minor prior to the recapitulation on the V7 should be sought. A close accounting of the transitional chords at 157-158 and 165-166 labelled a through h in Example 2, reveals, along with conspicuous F (albeit) major melodic outlines in the bass which welcome the coming tonal area, that all but chords f and h contain the tritone component

minor prior to the recapitulation on the V7 should be sought. A close accounting of the transitional chords at 157-158 and 165-166 labelled a through h in Example 2, reveals, along with conspicuous F (albeit) major melodic outlines in the bass which welcome the coming tonal area, that all but chords f and h contain the tritone component  /

/ , representing the ii° of f minor, with chord f actually rooted on the second scale degree (

, representing the ii° of f minor, with chord f actually rooted on the second scale degree ( ). Chord h is the only one devoid of these subdominant pitches. However, if we now allow ourselves to consider the specific spelling of its bass note—

). Chord h is the only one devoid of these subdominant pitches. However, if we now allow ourselves to consider the specific spelling of its bass note— —we appreciate that Stravinsky wants it to be thought of, as well, as a subdominant—perhaps the subdominant—built on the raised fourth degree of the f minor scale. (We should not mistakenly neglect to note that all of the chords a through h contain the fourth scale degree either in the form of

—we appreciate that Stravinsky wants it to be thought of, as well, as a subdominant—perhaps the subdominant—built on the raised fourth degree of the f minor scale. (We should not mistakenly neglect to note that all of the chords a through h contain the fourth scale degree either in the form of  or

or  .) In sum, the transitions, conceived around subdominant harmonies, yearn for arrival on the V7, and Stravinsky delivers the object of this yearning by placing the recapitulation at the appropriate transpositional level3 (see Example 6).

.) In sum, the transitions, conceived around subdominant harmonies, yearn for arrival on the V7, and Stravinsky delivers the object of this yearning by placing the recapitulation at the appropriate transpositional level3 (see Example 6).

Example 6

Now that we have a clear sense of the means and purpose that occasion the false recapitulation of the Danse theme, the next question can be posed. How does the composer "correct" the substitution and reset the tonal direction? Once we answer this, we can construct a schematic tracing the tonal movement for the entire Danse, and then move on to the final topic. The full recapitulation happens upon an enhanced  harmony (see especially the cello part) during 173 which plugs into a circle-of-fifths cadence formula in d taken up at measure 174. Identified as a sub-mediant, the

harmony (see especially the cello part) during 173 which plugs into a circle-of-fifths cadence formula in d taken up at measure 174. Identified as a sub-mediant, the  chord progresses to a broken chromaticized form of the super-tonic in 174 which repeatedly falls into the dominant (again, follow the cello and contrabass parts). From here the music builds, articulating contrapuntally the simultaneous fusion of functions. Subdominant, dominant and tonic (see the horns) are set into polyphonic strata generating a continuum (sub-mediant is brought in as well by the timpani). The melody of the horns outlines the interval

chord progresses to a broken chromaticized form of the super-tonic in 174 which repeatedly falls into the dominant (again, follow the cello and contrabass parts). From here the music builds, articulating contrapuntally the simultaneous fusion of functions. Subdominant, dominant and tonic (see the horns) are set into polyphonic strata generating a continuum (sub-mediant is brought in as well by the timpani). The melody of the horns outlines the interval  /

/ , the same interval that served as an

, the same interval that served as an  minor ii° in the previous section (

minor ii° in the previous section ( instead of

instead of  in that passage), forged here into the image of a two-pronged tonic.

in that passage), forged here into the image of a two-pronged tonic.

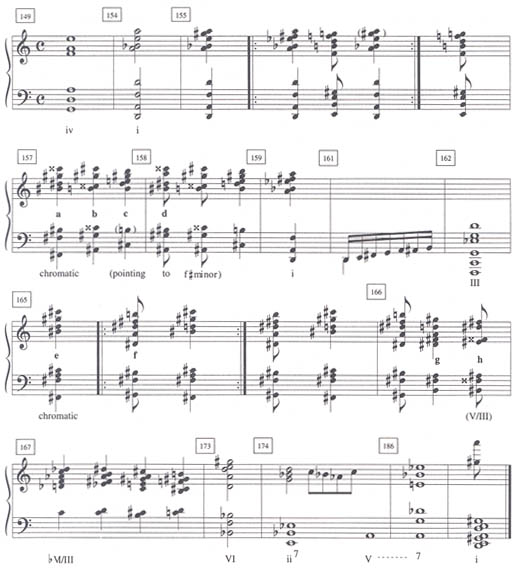

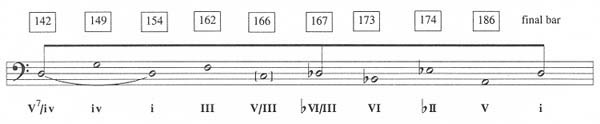

An overview of tonal progression in the Danse sacrale graphs as in Example 7.

Example 7

Thinking in d minor, 142 holds primarily to an enriched form of i, i.e., the V7/iv. At 149 resolution is made to the iv area. Return to the real i occurs in 154 and during this section, ornamental fluctuations enter the picture. A chromatic transition carries us to the relative major area at 162. The section in F winds its way toward a half-cadence on V, and a deceptive resolution links this passage with the recapitulation on  at 167. By the conclusion of the recapitulation at 173, the sub-mediant is reached, and the piece follows through a circle-of-fifths formula to its close. The true simplicity of the plan can be witnessed in the consistent motion of tonal centers by fourths and fifths, and its beauty can be grasped in the elegant contrast achieved by the exploration of one distantly related region at 167.

at 167. By the conclusion of the recapitulation at 173, the sub-mediant is reached, and the piece follows through a circle-of-fifths formula to its close. The true simplicity of the plan can be witnessed in the consistent motion of tonal centers by fourths and fifths, and its beauty can be grasped in the elegant contrast achieved by the exploration of one distantly related region at 167.

I believe that such planning extends over the entirety of The Rite of Spring. To close this discussion, it seems apropos to take stock briefly of the way the succession of tableaux pitch centers fits within the spectrum of tonal order. The Adoration begins with an introduction whose focal point is a minor, as demonstrated earlier. At 12 a false return of the opening bassoon call a semi-tone down in a minor leads into the Augers of Spring, Dances of the Young Girls at 13. The false statement is the hinge-pin that opens the piece up and invites extension. From 13 all the way through 56, passing through the Ritual of Abduction and Spring Rounds, the music pulls toward the  region (major and later minor), the tritone substitute area for a. At times it bows toward c minor (e.g., at rehearsal 54), plays with bitonal effects or adopts the octatonic vocabulary (37), but in general, pitch class

region (major and later minor), the tritone substitute area for a. At times it bows toward c minor (e.g., at rehearsal 54), plays with bitonal effects or adopts the octatonic vocabulary (37), but in general, pitch class  remains pervasively central. From the Ritual of the Rival Tribes through the finish of Part I, c takes charge as the new center. Often it is paired with

remains pervasively central. From the Ritual of the Rival Tribes through the finish of Part I, c takes charge as the new center. Often it is paired with  , or is colored in some other way; frequently its nearly related neighbors F major and G major provide pitch material for a passage; of course d as an important pedal tone causes an interruption at The Procession of the Sage, and The Sage (a scant four bars of Lento) sits upon

, or is colored in some other way; frequently its nearly related neighbors F major and G major provide pitch material for a passage; of course d as an important pedal tone causes an interruption at The Procession of the Sage, and The Sage (a scant four bars of Lento) sits upon  .4 But c regains control at 72 and presses on to the end of the first part. In retrospect it becomes clear that from 52 Stravinsky has maintained it as the principal tonal area to which all others ultimately defer. In short, Part I commences in a, substitutes

.4 But c regains control at 72 and presses on to the end of the first part. In retrospect it becomes clear that from 52 Stravinsky has maintained it as the principal tonal area to which all others ultimately defer. In short, Part I commences in a, substitutes  for a, and concludes in C, the relative of the original tonality.

for a, and concludes in C, the relative of the original tonality.

D minor is the broad tonality of the second part. Surely there is tonal oscillation to secondary areas from 89 through 128, though much of the Glorification, with its a pedal, already points back to d as a dominant, the  of the Evocation defining as the tritone substitute for that dominant. (The choice of b minor for the Mystic Circles, within the overall scheme of d minor, makes a particularly haunting key shift.) If we agree on d as the fundamental key of The Sacrifice, I am sure the reader has beat me to my conclusion: the Adoration, beginning in a and ending firmly in the relative, C, acts as a macro-dominant to the key region of the second part.

of the Evocation defining as the tritone substitute for that dominant. (The choice of b minor for the Mystic Circles, within the overall scheme of d minor, makes a particularly haunting key shift.) If we agree on d as the fundamental key of The Sacrifice, I am sure the reader has beat me to my conclusion: the Adoration, beginning in a and ending firmly in the relative, C, acts as a macro-dominant to the key region of the second part.

Where is the scandal in all this? Perhaps, the furor ignited by the Paris premiere in 1913 had more to do with Nijinsky's radical choreography than with Stravinsky's music. The second performance, conservatively choreographed by Massine, aroused no such response. It is possible that the story of initial outrage has been over-amplified through the decades, reinforcing one aspect of the music's ingenuity to the exclusion of others equally important. Taruskin has recently shown to what incontestable degree Stravinsky drew from Russian folk song in creating the work,5 and in so doing emphasizes its fundamental human quality. In a similar way, and toward a more balanced appreciation, what I hope to have suggested here is how deeply immersed the composer was, hearing through and working out his materials and his form, in the sensations and principles of traditional tonal harmony.6 The genius of the work lies not merely in its barbarous rhythms or convulsive orchestration,7nor does it reside in the much touted casting away of voice-leading or rejection of tonality, accusations far opposite the truth. It required a superior and sensitive mastery to produce the voice-leading in Example 5, and a remarkable foresight and tonal memory to lay out the broad key scheme as I have described it. Even the cluster or fusion chords point to an origin in the acciaccature of Scarlatti and other composers much earlier in the tradition. In no way can The Rite of Spring be dismissed as a heap of special effects, as some have alleged. The real miracle of The Rite of Spring which no hype or hurly-burly could presume to further enhance, is that the radical, new expressions and mannerisms contained within it burst forth out of a deeply marrowed feeling for the nature of voice-leading and tonal relations as manifest in Stravinsky's furthering of traditional intensities to a next more heightened level. No better argument speaks to support this than the fact that the most orchestrally exotic, wild and indeterminate section, the Introduction, and the most fiercely pagan and rhythmically determined section, the Danse sacrale, are both shaped by functional movement around the circle-of-fifths, and that these two functionally tonal segments, exclusive in their style with respect to all other sections, serve to bracket and cornerstone the whole expansive architecture.

1Rehearsal numbers are quoted as they appear in the 1967 reengraved edition, Boosey and Hawkes score No. 638.

2As early as 1959, Travis in his article, "Towards a New Concept of Tonality," discusses the d orientation of the Danse (Journal of Music Theory 3:257). He also proposes renaissance cadence patterns as prototypes for some spots in the Introduction, a compelling notion which might be more persuasively argued. Forte, in his The Harmonic Organization of The Rite of Spring, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1978) along with his critics—Craft, Moevs, and others—concurs that d functions as a tonal center for the Danse.

3I explain the half-step lower recapitulation as a local feature of the theme being magnified to the structural level, and as the natural culmination of carefully controlled functional implications. Also its reference to traditional deceptive cadence patterns is in evidence. While the applicability of these analytical viewpoints remains without question, yet another supporting factor needs to be mentioned. That is the pure notion of semitonal restatement as an end in itself. The half-step transposition between 142 and 167 already has its precedent in the relationship between the transpositional levels of the bassoon melody of the very introduction to Part I at 1 and 12—first the tune is stated in a minor, later a half-step lower in  minor.

minor.

4Mark how The Procession and The Sage are situated symmetrically on neighboring tones d and  , respectively, equidistant from the principal pedal tone c.

, respectively, equidistant from the principal pedal tone c.

5See Richard Taruskin, "Russian Folk Melodies in The Rite of Spring," Journal of The American Musicological Society 33: 501-543.

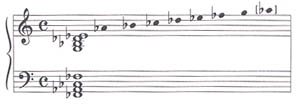

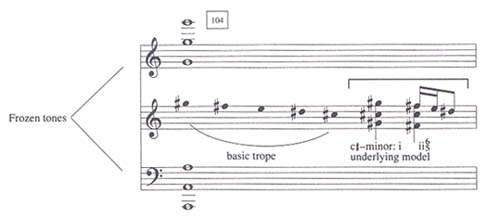

6Motives of other sections still manage to derive from traditional progressions. Two examples illustrate this. When x-rayed, the Glorification subject at 104 reveals a familiar skeletal progression from i to ii in

in  minor. Example 8 establishes the model by separating the added colorational tones a and

minor. Example 8 establishes the model by separating the added colorational tones a and  from the true functional chord pattern.

from the true functional chord pattern.

Example 8a

On the melodic level, it can be seen that the i-ii oscillation harmonizes the descending pentachordal trope made of scale degrees 5, 4, 3, 2, and 1 in the key of

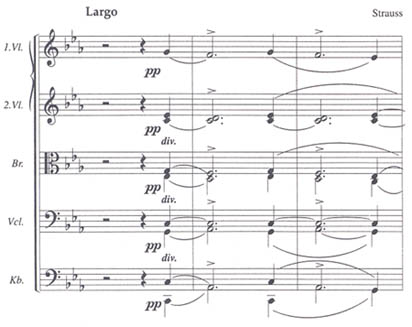

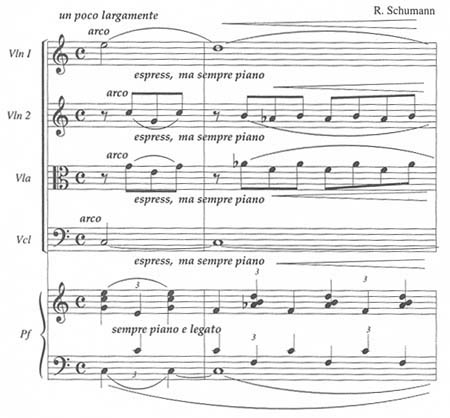

oscillation harmonizes the descending pentachordal trope made of scale degrees 5, 4, 3, 2, and 1 in the key of  minor. The underlying model here is common to many themes reaching back historically. Three immediately spring to mind, quoted below: the opening subject of Death and Transfiguration by Strauss, the principal theme of the first movement of Brahms' piano quartet Op. 60, and the B section subject from the second movement of Schumann's piano quintet, Op. 44. Note the kinship in tempo and declamation between the Brahms and Stravinsky.

minor. The underlying model here is common to many themes reaching back historically. Three immediately spring to mind, quoted below: the opening subject of Death and Transfiguration by Strauss, the principal theme of the first movement of Brahms' piano quartet Op. 60, and the B section subject from the second movement of Schumann's piano quintet, Op. 44. Note the kinship in tempo and declamation between the Brahms and Stravinsky.

Example 8b

Example 8c

Example 8d

Example 9 demonstrates that the playful motif at 135 from The Ritual Action of the Ancestors belongs to a lineage of I-V6-I progressions.

Example 9a

Example 9b

The bare prototype is classical in expression. Brahms would color it by changing the major V chord to an augmented sound—the quotation from the last movement of his G major violin/piano sonata exemplifies my point. Stravinsky carries the model a step further by adding further chromaticism.

7Texts such as Joseph Kerman's book, Listen, still tend to teach the work as hard-edged and assaulting:

What is conspicuously absent from The Rite of Spring is emotionality. Tough, precise, and barbaric, this music is as far removed from Debussy's impressionism or Berg's expressionism as it is from the old-line romantic sentiment of Strauss or Mahler . . . the music . . . is turned off as though by a switch . . . We may indeed regard this as a "primitive" treatment of musical form. Rhythm was at the heart . . . . (New York: Worth, 1972:313)

Such assertions at the very least require qualification. In matters of orchestration, is Stravinsky any more adventuresome than Berlioz in his particular epoch? Isn't he far less gratuitous than many instances in Strauss? In truth there is much Debussy in the work (all the best and worst parts, said the composer), and the opening, with its woodwind emphasis and descending chromatic bass line easily has as a precursor the opening of Ravel's Daphnis and Chloe Suite No. 2. Who is to determine "emotionality?" Stravinsky was, in his own words, the vessel through which The Rite of Spring passed. "Vessel" serves as metaphor for "medium," in the sense of "prophet," a person trained and conditioned to receive and effectively communicate a message from a higher source. My contention in this essay is that the inspiration of the Rite channelled itself through Stravinsky's finely tuned sense of tonal hierarchies and their affective powers, in which musical emotion is in fact rooted. I show in other notes here that Stravinsky's chord changes emulate very closely those found in music of 19th and 18th century composers of the mainstream tradition. His harmonic-emotional language divorces itself from earlier models not at all. Face it, there are gigantic V-I and IV-I effects straddling extended sections of the work, chosen precisely for the emotional response they will elicit. (Augers, Dances of the Young Girls and Ritual of Abduction link together on this principle, to offer one example). "Primitivistic form?" Superficially it may seem so, but a great deal of intricate calculation went in to determining at what moment to terminate a section, and by what pattern materials alternate within a section. Cone wrote a lengthy essay on stratification of diverse materials in Symphonies of Wind Instruments, and one could produce a paper of similar scope solely on the phrase organization of the fourteen bar section 135 -137 in the Rite. And what of the repetitiveness of many passages? Had not Beethoven already set the stage for that in the Pastoral Symphony? And who could deny that for Beethoven as for Stravinsky, rhythm provided a musical core? Compare the dissonant, repeated staccato chords in the Eroica first movement development section with those of the Augers of Spring.