Lessons from a World: Balinese Applied Music Instruction and the Teaching of Western "Art" Music1

The teacher does not seem to teach, certainly not from our standpoint. He is merely the transmitter; he simply makes concrete the musical idea which is to be handed on, sets the example before the pupils and leaves the rest to them. It is as though, in teaching drawing, a complex design were hung on the wall and one said to the students, "Copy that." No allowance is made for the youth of the musicians; it never occurs to the teacher to employ any method other than the one he is accustomed to use [sic] when teaching adult groups. He explains nothing, since for him, there is nothing to explain.2

The above passage describes an approach to applied music instruction far removed from that experienced by musicians trained in the world of Western "art" music performance. Indeed, "from our standpoint," as the author phrases it, what is described hardly might be categorized as music teaching at all. Yet the passage accurately and evocatively portrays a method of teaching music that has been practiced for centuries on the small Indonesian island of Bali, where it continues today to function as the primary form of music pedagogy in a culture renowned the world over for the brilliance of its music and the virtuosity of its musicians.3 Balinese musicians refer to their model-and-copy approach to music instruction as maguru panggul, which means, literally, "teaching with the mallet."4 It is an oral/aural tradition approach which does not employ music notation and which relies almost exclusively on a holistic demonstration/imitation mode of transmitting musical knowledge from teacher to student.

In this article, I present a preliminary cross-cultural comparative study between the Balinese maguru panggul method and applied music instruction in the world of Western "art" music, and propose ways in which the effectiveness of music teaching in the West5 might be enhanced through the application of certain Balinese-inspired teaching methods and philosophies. The majority of the work is devoted to a descriptive analysis of maguru panggul in Balinese drumming instruction. This descriptive analysis is followed by a brief comparative consideration of fundamental differences between Western and Balinese music pedagogy concepts and strategies and, finally, by a list of practical suggestions for Western music educators interested in incorporating Balinese-informed methods and ideas into their own teaching approaches. Through the application of a more "Balinese approach," I propose that Western "art" music teachers can promote greater self-reliance, enhanced stylistic comprehension, improved ensemble playing, a better sense of musical continuity and flow, and better memorization skills among their students.

I would like to note at the outset that my discussion is decidedly "unilateral," focusing exclusively upon how Western music teachers might benefit from the influence of Balinese pedagogical ideas and methods while ignoring the many advantages conventional Western methods have to offer with respect to the teaching of Western music. This unilateral orientation may lead some readers to the impression that I am out to show that Western pedagogical approaches are fundamentally flawed, and that the "Balinese way" is better suited overall to the demands of teaching Western music than established Western teaching methods themselves. This is definitely not my position. Given a choice between advocating either a strictly "Western" or a strictly "Balinese" pedagogical approach for applied instruction in Western music, I would certainly advocate the former. Fortunately, however, such absolute choices do not have to be made. We are free to learn from each other, and my purposes here are to discuss an interesting and effective way of teaching and learning music that radically contrasts with those familiar to us in the West, and to propose some ways in which we might learn from our Balinese counterparts in the music teaching profession.

Ethnomusicology and the Color of Musical Waters

I have approached this essay as an ethnomusicologist who specializes in the study of Balinese music, but also as a university music educator, performing musician (percussionist), applied music instructor, and culture-bearer of the Western "art" music tradition motivated by a desire to make my "specialized ethnomusicological knowledge" relevant and useful not only to those in my own field, but also to colleagues and peers in other music teaching disciplines. I am especially interested in reaching the educator whose work is involved at some level with the teaching of Western music performance, regardless of whether or not that person has an interest in Balinese music per se.

Ethnomusicologists are not typically expected (nor encouraged) to involve themselves in the business of how the performance of Western "art" music might best be taught.6 Here, I am venturing to involve myself in such business, believing that an ethnomusicological perspective on applied music pedagogy offers an interesting, provocative, and potentially valuable view not only of cultural and musical "others" but of ourselves as well: as musicians, as people, and specifically in this instance, as music teachers. Borrowing an analogy from Richard Kennell, in ". . . the same way that the color of the water may be invisible to the swimming fish,"7 the methods we conventionally use to teach music may become so familiar and entrenched as to become essentially invisible to us; and when we lose sight of just what it is we do, we risk the loss of critical vision that compels us to grow creatively.

Examining the way music is taught and learned in another culture can help us to bring our own teaching practices back into conscious view. From that perspective, we may be inclined to reassess our pedagogical approaches, consider alternative ways of doing things, and look for new solutions to old problems. My own experiences with Balinese music pedagogy have prompted such reassessment and exploration, and in writing this article I hope to inspire the reader to reflect upon what it means to "teach music" and to explore possibilities for teaching music effectively in new ways.

Lessons from a World Versus Lessons from the World

One scholar who has been involved actively in the business of how pedagogical methods of other cultures can serve to enhance the way we in the West teach Western music is Patricia Shehan Campbell.8 Her book, Lessons from the World,9 represents a landmark contribution to the literature on cross-cultural music pedagogy, and the present essay can be seen as a response to and extension of that work, as its title suggests.

In Lessons from the World, Campbell provides a compelling argument for placing greater emphasis on "aural skills and creative musical expression" in the education and training of young musicians and offers music teachers practical suggestions on how these goals might be achieved.10 In support of her argument, she draws heavily upon research concerning music teaching strategies in a number of non-Western cultures: Japan, India, Thailand, China, Indonesia, the Middle East, and Africa, as well as traditional folk musics of Europe, and American jazz.11

Referring to applied music instruction, she states, "The private studio lesson, the standard forum for instruction in Western classical music, could become more effective if teachers developed an understanding of universal patterns of music teaching and learning behaviors and applied these to their teaching."12 This statement nicely articulates my central premise here, except that I am interested in potential transferability to the Western context of one culture-specific pattern of music teaching and learning behaviors rather than "universal" ones. Thus, I am interested in lessons from a particular musical world rather than the world at large.

By limiting the scope of my discussion to just two music cultures, I hope to find a middleground between the broadly general scope of a work like Lessons from the World,13 on the one hand, and specialized ethnomusicological writings with little practical relation to the needs and interests of Western music educators not involved in the teaching of music of "foreign" world cultures, on the other. In seeking such a middleground, I hope to contribute to the locating of a productive space in which increased interaction between ethnomusicologists and other music educators can take place.

Comparing Bali and the West: The Issue of Music Notation

Western applied music teachers teach pieces that are notated. Balinese teachers who use the maguru panggul method teach pieces that are not notated. This "literate vs. aural" dichotomy may lead some to question the value of exploring the potential transferability of Balinese pedagogical methods into a Western context. However, similarities between the musicianship demands inherent in the musical repertoires of the two cultures override the significance of the notated/non-notated music issue.

Taking representative instrumental ensemble repertoires as a basis for comparison, the principal task of Western and Balinese teachers alike is to facilitate the student's ability to perform long, complex, pre-composed pieces of music with the utmost technical precision, appropriate musical style and expression, and ensemble sensitivity. Whether notated or not, compositions in both instances are "fixed," in the sense that rhythms, pitches, textures, timbres, and many other features of the music are for the most part predetermined. While improvisation plays an important role in the Balinese music learning process, it occurs relatively rarely in actual performance.14 While reading music notation plays an important role in the Western music learning process, actual performance situations very often demand that music be memorized, or be so nearly memorized that the score serves as little more than a general memory aid.

In short, a look beneath the surfaces of musical and cultural difference reveals that the technical and conceptual requirements faced by musical performers in Bali and the West are in fact closely related. That the Balinese musician is able to meet such requirements without the use of notation should render Balinese pedagogical models all the more interesting to Western music educators, especially given the current interest in non-notation-bound aural and kinesthetic methods for teaching music.15

"The teacher does not seem to teach, certainly not from our standpoint."16

The passage quoted at the outset of this paper was written by the late Canadian-American composer and ethnomusicologist Colin McPhee, whose passionate love for the music, culture, and people of Bali led him to establish residence there for about eight years during the 1930s. McPhee's musicological research and activities during that period resulted in a series of books and other publications that defined the field of Balinese music studies and set a standard for all subsequent scholarship in that area.17

McPhee was more than an exceptional music scholar and musician. He was also a gifted writer who possessed a talent for pulling the reader into his world of thoughts and images with but a single well-chosen phrase. His above-cited reference to the Balinese music teacher who "does not seem to teach, certainly not from our standpoint" is such a phrase, and it is a provocative remark that points in one way or another to all of the central questions to be addressed in this essay.

It begs the reader to ask: If the Balinese teacher does not teach, then how does the Balinese student learn to play music, and in the process, to develop skills quite readily in key areas of musicianship that Western students tend to find highly problematic, such as memory retention, comprehension of appropriate musical style and expression, musical continuity and flow, and ensemble playing sensitivity? It also prompts us to question just what, "from our standpoint," a teacher does when teaching music. What makes it seem like teaching when we do it, yet appear as something completely different within a context such as the Balinese one described by McPhee? Both Western and Balinese musicians are faced with the challenges of musical repertoires that feature complex, virtuosic, pre-composed, multipart works. Yet the differences between means of transmitting and acquiring the necessary skills to perform such works are so great that even to recognize the Balinese teacher as a teacher presents a challenge for the Western analyst. This makes for an interesting comparative situation. Similar ends achieved through vastly different means always make for interesting comparisons.

Let us now turn our attention to the Balinese world of gamelan music and examine the processes through which students there learn to play music from teachers who "do not seem to teach."

Balinese Gamelan and the Gamelan Baleganjur

As anthropologist Clifford Geertz has eloquently stated, Bali is a land whose "most famous cultural attribute is her artistic genius."18 There is perhaps nowhere on Earth where the arts flourish as they do in Bali. On this small, densely populated, primarily Hindu island in the center of the Indonesian archipelago, spectacular pageants, elaborate dance-dramas, evocative shadow puppet plays, and the captivating sounds of music ensembles known as gamelan are as essential to human existence as eating and sleeping.

Gamelan is the generic term for a variety of percussion-dominated Indonesian orchestras which characteristically feature bronze gongs, gong-chimes, and metallophones of various sizes and pitch ranges, as well as drums and cymbals. End-blown bamboo flutes (suling) and spike fiddle (rebab) may also be included, as well as zithers, bell-trees, and other instruments. While distinctive forms of gamelan are to be found on a number of the Indonesian islands, the best-known are those of the islands of Java and Bali.19

Bali is home to over twenty distinct forms of gamelan, each with particular associations to specific rituals or other performance contexts.20 The gamelan baleganjur, or "gamelan of walking warriors," is an ensemble consisting exclusively of hanging gongs and smaller hand-held gong-type instruments, multiple pairs of crash cymbals (cengceng), and a pair of drums (kendang), one "male" (lanang) and one "female" (wadon), each of which is played by a single player.21 It has been a traditional processional ensemble of war and death rituals for centuries and, since 1986, has also been used for a special type of music contest which features a flashy and virtuosic neo-traditional musical style, kreasi baleganjur—"creative" or "new creation" baleganjur.22

The lead instrument or "conductor" of the gamelan baleganjur is always the "male" drum. His part is inextricably tied to that of the lower-pitched (!) "female" drum, and the two drummers engage in extremely intricate and complex rhythmic interlocking throughout a kreasi baleganjur composition. Together, the male and female drums create one composite drum part through a type of imitative hocketing in which both drummers play almost the exact same part, but at a "sixteenth-note" interval of rhythmic displacement.23 A more delightfully difficult form of "rhythmic canon" would be hard to imagine. So integrally related are the drum parts that drummers will never practice alone. They will only practice together with a partner.

The drums, known as kendang, are double-headed and are held horizontally. Each drummer plays with a mallet (panggul) in his24 right hand, which is used to strike the larger, lower-pitched drum head. The smaller, left-hand head is struck by the open palm. A variety of stick, palm, and finger strokes create a rich mosaic of percussive timbres and syncopated accents between the two drums.

A kreasi baleganjur composition consists of a series of pre-composed variations, each known as a pukulan (literally, "beat"). The individual pukulan are presented within a large-scale, fast-slow-fast framework of "movements." Tempo and dynamics change frequently and sometimes dramatically during the course of a piece, and there is a good deal of musical contrast between the different sections. The lead drummer directs all musical changes and transitions as he plays.

Private music lessons, that is, one-on-one sessions between a teacher and student, are a rarity in Bali. As a rule, music learning takes place in full ensemble rehearsals. The major exceptions to this rule are private drum lessons, which occur with some frequency. The technical difficulties which drum parts present, together with the ensemble leadership responsibilities of the drummer, often necessitate that drumming be learned during individualized sessions between a student and a master teacher prior to full group rehearsals, especially in the case of "contest" genres like kreasi baleganjur, which feature newly composed pieces with extremely challenging drum parts. Most often, the drum teacher is also the composer of the work he teaches.

Because of the drum lesson's somewhat unique status in Bali as a pedagogical context in which private music lessons take place, and because of kreasi baleganjur's status as a musical genre that features one of the more demanding Balinese drumming styles, the baleganjur drum lesson provides an excellent case study for an illustration of the maguru panggul pedagogical method, and this will be our focus here.25

One of the leading teachers, composers, and drummers in the kreasi baleganjur movement since its inception in 1986 has been I Ketut Sukarata (see Figure 3), who was my principal teacher in Bali. The descriptive analysis of maguru panggul which follows is based primarily upon detailed observation, documentation, and videotape analysis of drum lessons taught by Sukarata in Bali from June to September 1992. While observation of lessons given by Sukarata to his Balinese students provided the main source of data, insights gained through my own course of study with him in the art of baleganjur drumming represent another important source of knowledge and understanding.

Interlude: Balinese Conceptions of Balinese Pedagogy

As was noted earlier, the term maguru panggul, as defined by the esteemed Balinese ethnomusicologist I Ketut Gede Asnawa (see Figure 3), means "teaching with the mallet." This is a term used with specific reference to the modeling/imitation based pedagogical method that one observes in the teaching of gamelan, whether within a formal or informal learning environment. A related term with broader applications is nuwutin, defined by another leading Balinese ethnomusicologist, I Wayan Dibia, as a "traditional teaching method emphasizing on [sic] imitating rather than analyzing."26 This term can be said to apply not only to music instruction but to a Balinese approach to education which informs virtually every aspect of cultural life, from dancing to painting to the harvesting of rice.

The terms maguru panggul and nuwutin, as they are defined by Balinese scholars, both indicate accurately what takes place in interactions between Balinese drum teachers and students, and also offer insights into the pedagogical values and concepts underlying such interactions. The central role of the mallet as a transmitter of musical information implied by maguru panggul, and the "either/or" distinction between imitation and analysis implied in Dibia's definition of nuwutin provide important clues concerning basic differences between Balinese and Western conceptions of what it means to teach music. The Balinese teacher functions as a modeler of ideal music whose methods are decisively anti-analytical. In the way he conveys music to the student and in the way he orients the entire learning process, his consistent aim is to present the musical whole without drawing undue attention to the parts of which it is composed. As we shall see, this "holistic" orientation fundamentally distinguishes the Balinese maguru panggul teaching method from more analytical and intervention-oriented pedagogical approaches familiar to us in the West, and helps to explain some of the potential advantages that a more "Balinese" approach may provide for those involved with the teaching of Western music.

The Baleganjur Drum Lesson:

A Case Study of the "Teaching With the Mallet" Method

"Teaching with the mallet"—maguru panggul—describes a process which quite literally captures the essence of interaction between teacher and student in a Balinese baleganjur drum lesson, and, in fact, in virtually any gamelan teaching situation. The mallet, or panggul, is the implement which connects player to instrument, turning a dance of playing motion into musically-patterned sound. More than his words or the sounds he produces when he plays, it is the teacher's mallet which first "tells" the student what he must know in order to play the music. The ability of the student to follow and mimic the motion of the teacher's mallet as he plays represents the first step on a complex path to musical competence and musicality.

In observing a baleganjur drum lesson in Bali, the first thing that strikes the Western observer is the absence of notated music. The teacher's performance demonstration of the musical material he teaches is the only "score" available to the student as he attempts to come to grips with the exact and highly complex musical materials he faces. Making matters all the more difficult and perplexing, at least from a Western perspective, is the fact that the teacher makes little or no attempt to tailor his demonstrations to the individual student's learning capacity. Rather than playing a few "measures" or even a single complete phrase of a musical passage and building up from there, the teacher plays through an entire pukulan, a complete "variation" section of a musical composition, which may be over a minute long. Right from the start, the passage is played as it would be in an actual performance: in full, with neither reduction in tempo nor any other modifications that might make the musical material more "manageable" for the student to comprehend and process. McPhee's assessment that the Balinese teacher ". . . simply makes concrete the musical idea which is to be handed on, sets the example before the pupils and leaves the rest to them"27 is supported by my own research findings.

Learning from the Mallet

As the demonstration performance of the pukulan begins, the student very intently focuses his gaze upon the mallet held in the teacher's right hand. As soon as the teacher begins to play on his drum, the student joins in immediately on his own, trying to follow and reproduce the guiding motion of the teacher's mallet as he plays. Mimicking the motion of the mallet is the first and key element in a process that will see the student gradually move towards re-creating the entire kinesthetic-musical "performance" of the teacher. The motion of the teacher's mallet is the closest thing in Bali to a notated version of the music—a symbolic code containing visually discernible musical data. In the early stages of learning, the student does not so much aspire towards capturing the sound and musical structure of what he hears in the teacher's playing as the physical manner and expression of what he sees.

As "the music" is transported from the teacher's mind and soul through his body, into his hands, and through his mallet, and is ultimately brought to life by the drum—which is itself thought of as no mere inanimate object but rather as a living being with a soul of its own—it enters the student's body and consciousness through an inverse process. As his mallet begins to approximate the movements of the teacher's, first the hands, then arms and body follow suit. Before he can play anything that sounds even remotely like "the actual notes" of the music, he is generally in full command of a vocabulary of movement and a style of playing that captures the essence of the musical passage while lacking most of its structural musical "content." In other words, the gestalt of the performance is intact before the specific notes and patterns begin to fall into place. In gestalt terms, the student's response to what he sees and hears the teacher play is based, at least initially, on perception of ". . . a complete and unanalyzable whole rather than a sum of . . . specific elements in the situation."28

Learning Without Listening: Direct and Immediate Imitation

Learning primarily through kinesthetic imitation, the student does not really listen to the teacher's initial demonstration of the pukulan. Instead, he jumps directly to the act of playing as soon as the demonstration begins, without concern for knowing what the music is "supposed to sound like" before attempting to perform it. This propensity for "jumping in" should not be unfamiliar to those who have taught music to small children. Anyone who has attempted to convince a class full of six-year-olds with plastic tambourines in hand to listen to a demonstration of a rhythm before they try to play it themselves is surely familiar with the "jumping in" phenomenon.

The natural impulse of children to play along with what they hear rather than to listen first and imitate later is extremely powerful. In the West, we teach children to suppress this "childish impulse." The tendency of a child to "interrupt" a music teacher's demonstration with "noise-making" is generally seen as a problem in need of corrective measures. The child's excitement and exuberance, however endearing, must ultimately be subdued if productive learning is to take place.

In Bali, the impulse to jump in right away and play along with the teacher is encouraged rather than discouraged, and in fact becomes the foundation of the learning method, for small children first encountering music and advanced students alike.29 Balinese imitative learning is imitative in the truest and most direct sense. Our own "rote learning" or "imitative" methods tend to be more analytical in orientation. In listening first and then playing back what is heard, the Western student actually "analyzes" music before attempting to play it. There is always a mediation between receiving the musical gesture from the teacher and realizing it in the physical act of playing; a mediation which occurs during the space of time between the demonstration and imitation performance acts.

Compared to the highly analytical mediation which takes place in the translation of notated symbols into musical sounds, the low-level analytical mediation involved in learning by imitation as generally practiced in the West seems refreshingly organic and natural.30 From a Balinese perspective, however, Western methods of imitative instruction appear excessively analytical. This is perhaps why Dibia, writing for a largely Western readership in his Ph.D. dissertation, defines the term nuwutin not only as a traditional Balinese method of instruction emphasizing imitation, but as a traditional Balinese method of instruction emphasizing imitation rather than analysis.31 The definition implies an important distinction between Balinese and Western conceptions of "imitative learning," which I suspect Dibia emphasized intentionally.

To the Balinese music teacher, the student's immediate transformation of music from a mode of reception to one of production is seen as normal and productive rather than problematic and disruptive. Mediation between the receptive and productive act, which in the West may take the form of reference to a notated score or any number of other types of intervention, is highly uncharacteristic in Bali, at least in the early stages of music learning. Michael Tenzer, in describing how Balinese students learn to play their parts on melodic metallophone gamelan instruments, states:

The musicians learn both by listening to what [the teacher] plays and, just as importantly, by watching the direction his mallet takes across the keys . . . . Reading music is a process of translating symbols into sounds; Balinese musicians bypass this stage entirely and learn music by transforming a received musical gesture directly into the physical act of playing.32

From Mimetic Imitation to Conceptual Learning

In the baleganjur drum lesson, we have seen that the transformation from "received musical gesture directly into the physical act of playing" described by Tenzer occurs initially at the level of the student's imitation of the teacher's mallet motion. This imitative motion initiates a process of learning which, through a series of stages, will ideally convert the purely imitative and "musically meaningless" physical actions performed by the student in the beginning into a well-executed, stylistically appropriate, and expressive performance of the pukulan modeled on the teacher's performance.

Building from the motion of his mallet, the student must transform a mimetic physical act of playing into precise and expressive musical performance. This transformation occurs as the accuracy and comprehensiveness of imitation increases until, in the later stages of learning, pure imitation gives way to the creative devising of more "conceptual" learning strategies which attend to the details of musical content. The teacher repeats his performance demonstration of the pukulan over and over again, and with each successive repetition the student moves closer to the ideal of musical competence.

Through the first several repetitions of the teacher's performance demonstration, proper movement and style begin to emerge in the student's imitative performances. His mallet guides his hand, and his hand guides his arm and then his body towards production of the proper sound-generating motions. As the "dance" of musical motion is mastered, the music as a form of expressive performance crystallizes before the passage has been fully "learned," that is, in our sense of learning correct notes, rhythms, stroke patterns, and the like.

Listening to what the student plays at this level of development, one hears a kind of "rhythmic rambling." This rambling is analogous to the "expressive jargon" phase of prelinguistic speech "spoken" by children during the second year of infancy. At this stage of linguistic development, the child produces ". . . a string of utterances that sound like sentences, with pause, inflections, and rhythms, but that are made up of 'words' that, for the most part, are nothing more than meaningless gibberish."33

Command of "the notes" does not develop until relatively late in the learning process and comes about in a highly nonlinear way. Small, scattered fragments of properly executed "patches" of notes begin to emerge here and there out of the student's semi-improvised, semi-imitative "rhythmic ramblings." One repetition after another, the patches of correct notes gradually become longer, and more of them start to pop out from the rambling texture until finally the musical structure begins to take shape and be recognizable. Mastery of "the notes," however, does not follow a linear progression. The accurate phrases are not achieved sequentially. Rather, they appear as small gems scattered sporadically throughout the pukulan, connected to one another by the stylistically recognizable, yet literally incomprehensible, rhythmic ramblings of sections not yet mastered.

At the point in the learning process when correctly played patches of music first begin to emerge out of rhythmic rambling, one notices that the student begins to listen to the teacher's demonstrations more often without playing along. This is because as focus shifts from the overall shape and style of the pukulan to specific details of its musical structure and form, learning strategies become more conceptual and analytical and less purely mimetic. The teacher does not respond to or explicitly guide the transformation of the student's learning strategies, however. His critical evaluations of student performance are generally limited to an overall assessment of "pas" or "belum pas," that is, "correct" or "not yet correct." An assessment of "not yet correct" results in a repeat of the demonstration and little more. Occasionally, the teacher will make use of physical gestures such as nodding of the head or exaggerated arm motions to draw attention to a particular problem area with which the student is struggling. He may even highlight his gestures with a sudden increase in dynamic level, but beyond such attention-focusing strategies, no concessions are made to the holistic integrity of the music. The pukulan continues to be demonstrated in an idealized, fully-realized form in each of the many repetitions the teacher provides.

Stock Phrases: An Instance of More "Conceptual" Learning

The lack of linearity in the transformation from rhythmic rambling to correct execution of musical material may appear as a random filling in of patches of music to an outside observer, but increased familiarity with Balinese musical repertoire reveals a more orderly learning process than is initially evident. The patches that are learned first are usually what I will call "stock phrases". These are standard patterns idiomatic to a genre which often cross between genres, as well. For those familiar with jazz terminology, such stock phrases might be compared to jazz "licks." They may range in length from a short, cadential flourish to a complete section of a pukulan, perhaps sixteen "measures" long, which is inserted into the piece as a kind of trope. The more extensive a student's musical repertoire is, the more stock phrases he will have in his memory bank, and the more quickly he will learn.

Once recognized by the student, located within the structure of the new pukulan, and incorporated into his performance, a stock phrase becomes a kind of structural pillar around which the pukulan as a whole begins to take shape. Sections of the pukulan directly leading up to and away from this pillar are mastered more quickly than others further away. A single pukulan may contain two, three, or even four stock phrases, and the latter stages of learning involve a strategic process of linking these phrases together with ever-increasing accuracy and refinement. The stock phrases provide points of orientation and direction within the larger musical design, enabling the student to progress from mere mimicry of the teacher's motions to a combination of imitation and cognitive structuring strategies that help to gradually turn rhythmic rambling into correct technical execution. Since stylistic and "interpretive" learning of the music precede "note learning," by the time the student can finally play the notes, he is already playing musically. Because of the teacher's lack of intervention, the student's progression to this level of competence requires an extremely high level of self-reliance and problem-solving ingenuity.

Engendering A Holistic Conception of Music:

Interlocking, Run-Throughs, and Ensemble Environments

Promoting self-reliance on the part of the student is an important goal of the Balinese teacher's approach to teaching, and this may help us to understand the "logic" behind his unfamiliar ways. Even more significant in this regard is the grounding of teaching methods in a central philosophy that stresses the importance of inculcating in the student a holistic conception of the music he learns. This philosophy is manifest in the holistic approach to teacher performance demonstrations of pukulan discussed thus far, and also in the reluctance of the teacher to analyze and "break down" music for the student's sake, since analysis by definition draws attention to specific aspects of the music rather than to the musical whole. It is manifest in other aspects of Balinese baleganjur drumming instruction as well, including the pedagogical tendencies of the teacher to interlock rather than play in unison with the student whenever possible, to insist upon complete run-throughs of musical compositions throughout the learning process, and to foster an ensemble environment even in "private" drum lessons. A brief look at these three tendencies of baleganjur drumming pedagogy will help to clarify the relationship between holistic ideals and Balinese music teaching practices.

We will begin with the issue of "interlocking." Throughout his teaching of a pukulan, the teacher functions almost exclusively as a provider of repeated "ideal" musical demonstrations. What he actually plays, however, changes in successive repetitions as the student's competence increases in later stages of the learning process. Recalling that the "male" and "female" drum parts are conceived of as inseparable components of a unified whole, one finds that from the teacher's standpoint, either one of the two parts played in isolation is essentially meaningless musically. Thus, as soon as any musical patch within the pukulan being taught is even tentatively mastered by the student, the teacher automatically shifts from the part he has been demonstrating to the other, complementary part, so as to make the music as complete and as whole as possible. He then proceeds to shift back and forth between the two parts throughout the rest of the lesson, demonstrating the student's part in sections not yet learned and playing the interlocking part in those already fully or even just partially learned. By interlocking with the student at the earliest possible moment, rather than playing together with him in unison, the teacher aims to divert the student's attention away from exclusive focus on his own part, and towards a holistic perception of the complete drumming texture.

Once this aim has been achieved, the next objective is to divert the student's attention away from the pukulan itself. When the student's command of the pukulan finally enables him to play it through from beginning to end while the teacher plays the interlocking drum part, the pukulan immediately ceases to be treated as a discrete musical entity. Just as the student is not to conceive of the drum part he learns as possessing a separate musical identity, he is not to conceive of the individual pukulan as having a separate identity either. The pukulan becomes an integral and inseparable part of the piece to which it belongs, never to be played in isolation again. After the initial process of learning, it is generally only played in the context of run-throughs.

Outside of learning new musical material, practicing and rehearsing music for Balinese musicians consists of run-throughs and little else. Pieces are almost always played from start to finish, or, in the case of compositions that are still being learned, from start to whatever point in the piece has already been covered. The run-throughs are characteristically played at full tempo, and it is extremely rare for the teacher to isolate specific problem spots or sections to work on independent of the rest of the piece. If a mistake is committed that causes the student to stop playing, he must return to the beginning of the piece and try again. The question of picking up from somewhere in the middle does not arise.

So much time and energy is spent on repetition and full run-throughs that the piece is eventually committed to the student's memory as something like a solid block of musical material, rather than as a connected sequence of sections of music. In Western music performance, transitions are usually perceived as the most "dangerous" points in a piece; as moments where memory lapses most often occur, mistakes are most frequently committed, and the tightness of ensemble playing is most vulnerable. Multiple repetitions of "top to bottom" renditions of a piece largely alleviate such problems in the Balinese context.

We have so far seen how the teacher's ideal of holistic musical presentation applies to music demonstration methods, treatment of complementary interlocking parts, and the linear integrity of musical compositions. This same ideal applies to his efforts to furnish a learning environment, even in "private" lessons, wherein the student must immediately attend to the demands of playing in an ensemble context. Drum lessons generally take place out-of-doors. Passers-by from the village who stop to watch and listen are characteristically invited to join in and play. Instruments are usually close at hand, and it is not uncommon to observe a "private" drum lesson in which the teacher and drumming student end up being accompanied by six or seven other players, sometimes including young children, who busy themselves marking strokes on the gongs, hammering out an ostinato melody, or beating time on a small kettle-gong called kempli. The more extra players join in, the better. There is no closing of the studio door so that teacher and student can concentrate their attention fully on their musical objectives, free of outside distraction. Rather, an ensemble environment is created whenever possible.

Summary of Maguru Panggul in Baleganjur Drumming Instruction

Having explored the maguru panggul method within the kreasi baleganjur drum lesson context, it will now be helpful to summarize five of its most important features before continuing the discussion. In maguru panggul, the following features are evident:

(1) No musical notation is used. The teacher relies exclusively on performance demonstrations to present musical material to the student.

(2) The teacher's demonstrations always aim to present the music to be learned in a format that is as complete and as polished as possible. Thus, very long musical passages demonstrated at full tempo in "concert performance style" are the norm. The demonstration functions as an idealized model to be emulated by the student.

(3) The student's principal method of learning involves direct imitation of the teacher's model-performance demonstration, which is repeated as many times as necessary. Imitation of the visible-kinesthetic aspects of the teacher's performance, beginning with the motion of his mallet, precedes the student's comprehension of aural-musical aspects, and command of musical style and expression precede mastery of musical content (i.e., "the notes").

(4) The teacher provides repeated model-demonstration performances and determines when a musical passage has been adequately learned, but offers little in the way of specific criticisms, potential problem-solving methods, or other forms of guidance to the student. As a result, the student must be highly self-reliant in devising learning strategies. These strategies tend to be purely imitative during the early stages of the learning process but become more conceptual and detail-oriented later on.

(5) The teacher's primary goal is to enable the student to conceive of the entire musical composition holistically. He achieves this goal through presentation of "ideal" performance demonstrations, attempts at "filling out" the musical texture to the greatest extent possible, and avoidance of forms of intervention and analysis that might draw attention away from the musical whole by focusing attention on its constituent parts.

Applied Music Pedagogy, "from our standpoint" and from Theirs

As transmitters of their own musical heritage, teachers shape the musicianship of their students, demonstrating through their own performance the standards for tone quality and technique. They listen to students and respond to their individual needs regarding sound production, phrasing, and articulation. They offer ways to improve students' literacy skills, including sight reading ability, and define new symbols as they occur in the notated repertoire. They recommend methods of practice, advise means for memorizing a work, and suggest opportunities for the creative expression and interpretation of a piece.34

The above passage by Campbell provides a nice overview of what teachers who do seem to teach "from our standpoint" do when they teach.35 Western music teachers, like Balinese teachers, employ performance demonstrations—although in a more limited and problem-focused way than do their Balinese counterparts—but there the similarity apparently ends. Western teachers are very actively committed to an objective of teaching their students how to learn. They respond in a unique manner to the capabilities and limitations of each student, provide recommendations, offer advice, and make suggestions. They intervene on behalf of their students in a wide variety of ways, and their critical insights, analytical skills, task-setting and problem-solving abilities, and powers of explanation are central to their effectiveness. While the student is ultimately responsible for learning, the teacher takes on the responsibility of creating, mapping out, and monitoring an individualized instructional program aimed at maximizing the student's learning potential. This is the antithesis of McPhee's archetypal Balinese music teacher, who ". . . sets the example before the pupils and leaves the rest to them. . . ," who ". . . explains nothing, since for him, there is nothing to explain" and who, in the end, "does not seem to teach," since he does so few of the things that we expect a music teacher to do.

And yet, the Balinese teacher definitely does teach. The difference between him and his Western counterpart is one of philosophy, not commitment. His methods are not grounded in analysis and intervention, but in the holistic transmission of the music he teaches. If, from our standpoint, the Balinese "teacher does not seem to teach," from a Balinese standpoint, we perhaps teach too much. In any case, the Balinese music student certainly seems to learn—to learn very well, in fact—and readily to develop skills and capacities in key areas of musicianship which we in the West often find frustratingly elusive and difficult to master ourselves, let alone to convey effectively to our students: memory retention, musical continuity and flow, stylistically appropriate and expressive playing, and ensemble sensitivity.

The advantages of the maguru panggul method with respect to development of musical skills in these and other areas is to be found in its holistic orientation. By presenting the music to the student's consciousness in a form that is always as close to an ideal and uncompromised performance as possible, the Balinese teacher teaches his student how the music should be played rather than how to play it, and the student learns what the music should sound like but must teach himself how to learn it. As a result, he develops both a capacity for seeing the "big picture" and a degree of self-reliance that enable him to excel in domains of music learning which tend to present greater challenges for his Western counterpart.

My fieldwork training in gamelan performance in Bali, and especially my studies of baleganjur drumming with I Ketut Sukarata, frequently presented situations where I found myself studying the same music over the course of the same time period as Balinese fellow student-musicians, most of whom were only teenagers. Each of these situations led to essentially the same result. Armed with highly-developed percussion technique, the seemingly "magical" ability (from a Balinese point of view) to transcribe, notate, and read music, and an arsenal of learning and performance strategies imported into the Balinese context from my training and experience as a professional "classical" percussionist and jazz drummer, I was able to learn much faster than the Balinese students through the early going. In fact, I often found it difficult even to watch their lessons, since progress was so painfully slow. However, as time wore on, my rate of learning leveled off, while theirs accelerated dramatically. Within a week or two, they caught up to me and zoomed right on past; but it was not the quantity of material they were able to learn so much as the quality of their learning that most impressed me. The maturity, self-assurance, and effortlessness of their playing was remarkable, especially given their youth and the fact that what I would hear them play one day with such style and panache had been nothing more than a chaotic mess of sound just a day or two before. Furthermore, once they learned something they never seemed to forget it, which was more than I could say for myself; and their performances of long, multipart works flowed seamlessly from one section to the next, whereas mine tended to plod much more deliberately and self-consciously from one part to another.

In retrospect, it was my reflections upon this oft-repeated pattern of inferior learning on my part, combined with insights gained through countless hours analyzing videotapes of Balinese drum lessons, that sparked the curiosity from which this article has arisen. In trying to make sense of the pattern, one explanation I came up with was that what I was dealing with was essentially a cultural phenomenon—this was, after all, Balinese music, and it was only logical that Balinese musicians would end up playing it better than I could, regardless of how hard I worked or how much culturally-translated musical ability I brought to the situation. I still maintain that this theory is at least partially true.

Another explanation, however, stemming more from analysis than reflection, was that the way in which the Balinese students learned music was at least as important a contributing factor to their achievements as the cultural and musical "insider" status they brought to the music-learning challenges we shared in common. Entertaining this possibility led me to theorize that, as a general rather than culture-specific method, the traditional Balinese way of learning music presented some distinct advantages which transcended the Balinese context, that these advantages would be particularly relevant to the concerns of Western "classical" musicians, and that to a certain degree, they were accessible to us and cross-culturally transferable. Certainly, there were practical constraints that limited this potential transferability. One major constraint was to be found in the conventional format of Western applied music instruction itself. In one one-hour private lesson per week, the potential effectiveness of teaching methods based largely upon demonstration, imitation, repetition, and aural learning were more limited than in the Balinese pedagogical context, where teachers and their students often worked together several times a week. Nonetheless, I held to a belief that intelligent adaptation of Balinese pedagogical methods, if not full-scale adoption of such methods, could be of great value.

My own experiments with Balinese-inspired approaches over the past couple of years, both as a teacher and player, have supported my theories, and by way of conclusion, I would like to offer a list of ten suggestions for Western music teachers with an interest in incorporating maguru panggul-influenced methods and ideas into their teaching. Application of these suggestions should ultimately result in greater emphasis on demonstration/imitation-based pedagogical methods, modification of established Western "rote" teaching and learning approaches, a reduced level of teacher input and feedback relative to student problem-solving challenges, and development of strategies that encourage students to conceive of the music they learn more holistically and less analytically. I acknowledge that my suggestions have their origins in hypothesis and personal experience rather than in conclusive experimental findings. Large-scale assessment of their effectiveness will require a long-term controlled study that awaits future research.

Ten Suggested Balinese-Derived Methods for the Teaching of Western "Art" Music

(1) Increase the amount of time spent on direct model-and-imitation teaching methods relative to that spent on methods of learning which involve music reading. This suggestion applies to the teaching of advanced students as well as to less advanced students.

(2) In providing demonstration models of musical passages, experiment with playing long passages of material all at once rather than breaking passages down into single measures or phrases. By presenting musical material in a more holistic way, you will allow the student to work from "the big picture" to the level of detail, rather than vice-versa. This will engender a better sense of musical continuity and will lessen the likelihood of problems such as memory lapses.

(3) When demonstrating musical material for the student, do not hesitate to play passages as you would in actual concert performance: at full tempo, with all appropriate ornamentation and other forms of nuance, and in a musically expressive manner. Again, a more holistic manner of presentation will ultimately result in the student's development of a more holistic musical conception.

(4) When teaching young and inexperienced students, refrain from discouraging "interruptions" and "playing along" during your performance demonstrations. Whether you are teaching advanced or less advanced students, encourage students' attempts to mimic your performance as you play and instruct them to strive to capture the style and flow of the work before becoming concerned with "the notes." This suggestion will be especially challenging for the college-level music teacher, whose students' learning strategies and conditioning are so fundamentally centered around a listen-before-playing and notes-before-interpretation approach.

(5) Facilitate approaches to imitative learning that are as attendant to physical actions of movement and gesture as they are to the musical sounds, pitches, and rhythms which that motion produces. Comprehension and command of the kinesthetic dimension of musical performance are important first steps towards the development of both stylistic and technical musical competence.

(6) Be more judicious in the assigning of exercises and other interventive methods aimed at providing the student with strategies for solving musical problems. Compel the student to become more self-reliant and creative as a problem-solver by not offering guidance and advice in every situation where you feel that you can.

(7) Be less concerned with setting carefully-calibrated and "manageable" tasks and goals for the student and more concerned with presenting musical materials in a holistic manner right from the outset. Rather than helping to build up the student's knowledge and command of a piece in a sequential, step-by-step manner, try presenting large "chunks" of music at a time, and entrust the development of musical competence to modeling, imitation, repetition, and the student's own creative resourcefulness.

(8) Have the student play from the beginning to the end of works as often as possible, and in the case of pieces that are not yet fully learned, from the beginning to the point already studied. This strategy will help improve memory skills and musical flow and continuity.

(9) Create an "ensemble environment" for student learning whenever possible. Play duets, provide accompaniment on piano (or other instruments), and create and seek out opportunities for student ensemble playing experiences outside the lesson. In these ways, you will help the student to develop better ensemble playing skills, to conceive of what she or he plays in context rather than in isolation, and to experience the joys of creating music as a social and interactive experience.

(10) Play more and talk less. Major research studies on applied music instruction in the West have shown that demonstration-only methods of teaching are significantly more effective than either verbal-description-only methods or methods which combine demonstration and verbal description, but that in actual practice applied music teachers talk four times as often as they play when they teach.36 Such findings need to be taken with a grain of salt and certainly should not prompt us to dispense with "verbal" methods that have long proven effective in our teaching. Nonetheless, the "apparent contradiction"37 between theory and practice suggested by these studies indicates that we should at least experiment with approaches to teaching which put greater emphasis on nonverbal methods, and that we might look to performance demonstration-intensive models like maguru panggul for ideas and strategies relating to their implementation.

Conclusion

The Balinese maguru panggul method represents an approach to applied music pedagogy which, for all intents and purposes, turns conventional Western standards of good music teaching upside-down. Indeed, the Balinese teacher "does not seem to teach, certainly not from our standpoint," but if we allow ourselves to move away from that standpoint and look at things from a different angle, we discover that the Balinese teacher's unfamiliar methods and the holistic philosophy towards music which underlies them are relevant not only within the context of his own musical world but in ours as well. I neither expect nor desire to revolutionize applied music instruction in the West with this essay, but I do hope that those who read it will be inspired to think again about what it means to "teach music," and will find something of practical value in the described methods of master Balinese music teachers like I Ketut Sukarata, who may not seem to teach, but who most certainly do.

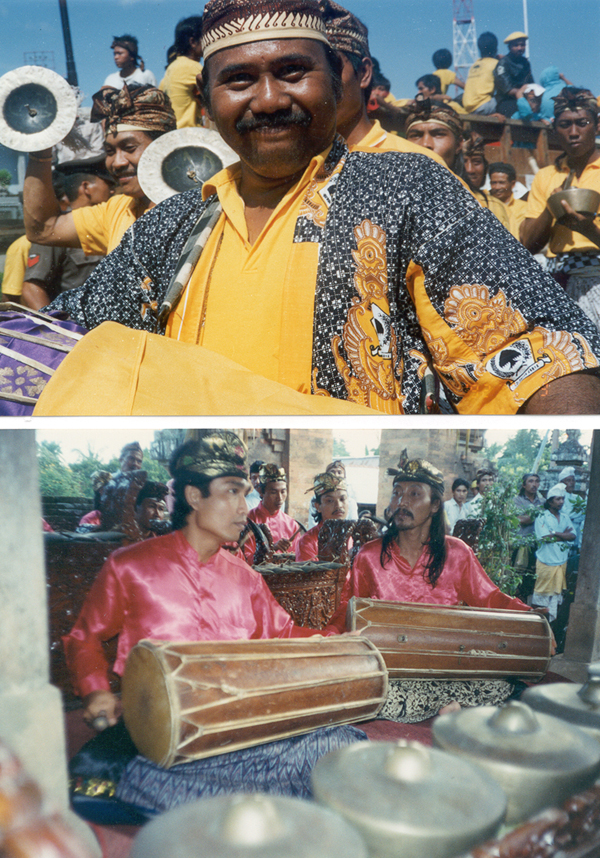

Figure 1. Drummers leading a performance at a baleganjur contest in Kintamani, Bali.

Figure 2. The lead drummer directs the cymbal (cengceng) section.

Figure 3. I Ketut Sukarata (top) and I Ketut Gede Asnawa (bottom left)

1I would like to thank Dale Olsen, Douglass Seaton, Jeffery Kite-Powell, Lee Riggins, Richard Kennell, Jane Clendinning, Paul, Rita, and Joel Bakan, and Marilyn Campbell for their criticisms, suggestions, and support.

2Colin McPhee, "Children and Music in Bali," in Traditional Balinese Culture, ed. Jane Belo (New York: Columbia University Press, 1970), 232-33.

3The introduction of a Western-inspired Balinese music notation system and other Western influences of recent decades have had an impact on teaching methods used in the Balinese performing arts conservatories such as Sekolah Tinggi Seni Indonesia (STSI), but beyond these exclusive environs the traditional aural methods described in the opening quotation and throughout this essay have remained largely intact throughout Bali. For an insightful discussion of the impact of Western-inspired music notation systems on Javanese music culture, see Judith Becker, Traditional Music in Modern Java (Honolulu: The University Press of Hawaii, 1981). This book is also recommended for its inclusion of important information relating to various aspects of Javanese music pedagogy.

4This translation was provided by I Ketut Gede Asnawa during an August 1992 interview with the author in Denpasar, Bali.

5Following Campbell's model, the terms "West" and "Western" will be used to refer to European and European-derived "art" music, and to the cultural ideas and practices surrounding this music. See Patricia Shehan Campbell, Lessons from the World (New York: Schirmer Books, 1991), xiii n.

6Ethnomusicologists have, however, involved themselves in the business of how the musicological study of Western "art" music might best be approached, and also have concerned themselves with the issue of what should be included in a standard curriculum for education and training in Western music by advocating the inclusion of musics from outside the Western "mainstream" and providing teaching materials that facilitate such inclusion. For an example of the former, see Bruno Nettl, "Mozart and the Ethnomusicological Study of Western Culture: An Essay in Four Movements," Yearbook for Traditional Music 21 (1989): 1-16. For two of many examples of the latter, see Dale A. Olsen and Selwyn Ahyoung, "Latin America and the Caribbean," and Han Kuo-Huang, Ricardo Trimillos, and William M. Anderson, "East Asia," in Multicultural Perspectives in Music Education, eds. William M. Anderson and Patricia Shehan Campbell (Reston, Virginia: Music Educators National Conference, 1989), 78-117, 238-78.

7Richard Kennell, "Towards a Theory of Applied Music Instruction," The Quarterly Journal of Music Teaching and Learning 3, no. 2 (1992): 7.

8Another is John Blacking, although his concern is more with theoretical conceptions of human musicality than with providing practical directives for music educators. See Blacking, How Musical Is Man? (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1973), 89-116.

9Patricia Shehan Campbell, Lessons from the World (New York: Schirmer Books, 1991).

10Ibid., 305.

11Ibid., 101-206.

12Ibid., 278.

13The vast cross-cultural scope of Lessons from the World makes it an extremely valuable resource for music educators, but at the same time presents problems. I agree with Dale Olsen, who, in reviewing the book for Music Library Association Notes 49, no. 1 (September 1992): 165-66, states that his ". . . only criticism is that such a grandiose undertaking by one author understandably leads to some oversimplifications (165)." Examples of such oversimplifications occur in the section on Indonesian music (143-149), where Campbell does not clearly distinguish between her references to the music cultures of Java and Bali, and, by essentially "meshing" these two related but distinctive music cultures into one, ends up drawing conclusions that are not always entirely accurate (see pp. 144 and 147). Cross-cultural comparative work of any kind can never fully avoid the pitfalls of oversimplification and broad generalization, and the present article is certainly not immune from such problems. Attempts at "universalist" and "global" approaches to cross-cultural comparison are especially problematic, however, and I tend to support ethnomusicologist Steven Feld's claim that in cross-cultural research, ". . . broad meaningful comparisons will have to be based on accurate, detailed, careful local ethnographic models." See Feld, "Sound Structure as Social Structure," Ethnomusicology 28, no. 3 (1984): 385.

14This is at least true within the context of particular musical genres such as kreasi baleganjur, which will be the focus here.

15See Campbell, Lessons from the World, for a comprehensive overview of such methods.

16McPhee, "Children and Music in Bali," 232-33.

17McPhee's two most influential publications relating to Balinese music and culture are Music in Bali (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1966), the most comprehensive English-language study of Balinese music available, and the charming, autobiographical A House in Bali (1947; Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1991), in which the author recounts his experiences in Bali during the 1930s and, in the process, offers some wonderful narrative descriptions of Balinese musical activities of that period.

18Clifford Geertz, The Interpretation of Cultures (New York: Basic Books, 1973), 400.

19For accessible introductory surveys of Javanese and Balinese gamelan traditions, see Neil Sorrell, A Guide to the Gamelan (London and Boston: Faber and Faber, 1990), which deals with the Central Javanese tradition; Michael Tenzer, Balinese Music (Berkeley and Singapore: Periplus Editions, 1991); and Ward Keeler, "Musical Encounter in Java and Bali," Indonesia 19 (1975): 85-126.

20See Michael Tenzer, "KOKAR Den Pasar: An Annotated List of Gamelan on Campus," Balungan 1, no. 3 (1985): 12.

22For a comprehensive study of the gamelan baleganjur, see Michael B. Bakan, "Balinese Kreasi Baleganjur: An Ethnography of Musical Experience" (Ph.D. diss., University of California, Los Angeles, 1993).

23The parts for melodic instruments of Balinese gamelan music such as instruments of the gangsa type (keyed metallophones) are structured on a similar male-female imitative interlocking principle. The composite interlocking melodic parts are known as kotekan. The individual instrument parts which make up a kotekan are called sangsih and polos (corollary to the lanang and wadon drum parts). Kotekan function as embellishments or "flowers" of the main, slow-moving nuclear melody (pokok). For more on kotekan and other melodic aspects of Balinese gamelan music, see Wayne Vitale, "Kotekan: The Technique of Interlocking Parts in Balinese Music," Balungan 4, no. 2 (1990): 2-15, Michael Tenzer, Balinese Music (Berkeley and Singapore: Periplus Editions, 1991), 41-47, and Jeanne Bamberger and Evan Ziporyn, "Getting It Wrong," The World of Music 34, no. 3 (1992): 22-56, in which Ziporyn presents an interesting reflective case study relating to his own experiences as a student of Balinese music.

24Since the Balinese drumming style discussed here is performed and taught only by males, I have chosen to use male pronouns for "generic" individuals throughout in my description and analysis of Balinese music pedagogy. It should be noted, however, that in Balinese musical genres other than baleganjur, and especially in gong kebyar, there has been a movement involving the establishment of all-female gamelan groups in recent years.

25Although the case study concerns drumming specifically, I am not really dealing with "instrument-specific" pedagogical techniques or strategies. Rather, the focus is upon a pedagogical method which stresses specific approaches to imitative learning and holistic musical presentation. The transferability of such methods should have as much relevance to the concerns of flute, violin, or piano teachers (and even voice teachers) as to those of teachers of "non-pitched" percussion instruments, and should also be of interest to classroom instructors involved in the teaching of ear training. Just as the surface differences between Balinese and Western music mask strong fundamental similarities relating to basic demands of musicianship, the surface differences between melodic instruments and non-melodic percussion instruments can lead to a highly exaggerated and sometimes inappropriate sense of pedagogical differentiation on the part of Western music educators. In the West, some are inclined to believe that non-pitched percussion instruments do not pose the same kinds of teaching and learning challenges as melodic instruments. This is certainly not the case in Bali, where the art of drumming represents the ultimate challenge of instrumental performance.

26I Wayan Dibia, "Arja: A Sung Dance-Drama of Bali; A Study of Change and Transformation" (Ph.D. diss., University of California, Los Angeles, 1992), 383.

27This quotation comes from the passage of Colin McPhee's "Children and Music in Bali," 232-33, found at the beginning of this article (see note 2). Subsequent excerpts from this same passage included in the remaining portion of the text will be placed in quotation marks but not cited.

28Webster's New Twentieth-Century Dictionary of the English Language, 2nd ed., s.v. "Gestalt psychology."

29This seems to be true for many other world music cultures as well, including Bulgaria. See Timothy Rice, May It Fill Your Soul: Experiencing Bulgarian Music (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994), 65-66.

30For an overview of imitative learning approaches in Western music pedagogy, see Campbell, Lessons from the World, especially the first part of Chapter 11 (212-27), "The Music Learning of Children," which discusses the Dalcroze, Orff and Kodaly "classic" methods, and a section later in the book on the Suzuki method (285-87).

31Dibia, "Arja: A Sung Dance-Drama of Bali; A Study of Change and Transformation," 383.

32Michael Tenzer, Balinese Music (Berkeley and Singapore: Periplus Editions, 1991), 106.

33Diane E. Papalia and Sally W. Olds, A Child's World (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1975), 92.

34Campbell, Lessons from the World, 276.

35For a number of interesting case studies of applied music lessons at the university/conservatory level, see Henry A. Kingsbury, Music, Talent, and Performance: A Conservatory Cultural System (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1988).

36See Kennell, "Towards a Theory of Applied Music Instruction," 7.

37Ibid., 7.