Reflections on the Relationship of Analysis and Performance1

Introduction

In their common endeavor to make and deliver personal interpretations about musical compositions, the activities and preoccupations of analysts and performers of music intersect in several notable ways. Both analysts and performers begin, presumably, with an emotional response to or fascination with an individual work that accounts for the choice of work to interpret, followed by extensive consultation with the notated score;2 both require some combination of acquired knowledge and skills as well as appropriate musical intuition; and both must make overt or covert, formal or informal, decisions about musical structure for the purpose of transmission to a reading or listening audience.

Interest in the nature of the relationship between analysis and performance has inspired great diversity in approaches to the subject. In much of the secondary literature, however, the relationship is portrayed as a didactic one in which the performer, as practitioner, takes on the role of apprentice to the analyst, who acts as the advisor on abstract matters concerning musical structure. This inequity can be viewed from two opposing angles, one from which the analyst is mentor, the other from which the analyst is servant to the performer. From either perspective, the roles of analysis and performance are not equal or balanced. In the final result, the role of analysis is ultimately one of utility to performance, even if in the position of tutor. Furthermore, most of the literature on the relationship between analysis and performance is published by scholars in theory and analysis, and appears in publications that are not routinely read by performers, and, therefore, has little influence on, or even alienates, performing musicians through its often technical language and sometimes dogmatic tone.3

In contrast to this viewpoint that indicates inequitable roles for analysis and performance, a different, but still prevalent, assumption is that a reciprocal relationship exists between them, that they are fundamentally parallel activities. As Leonard Meyer puts it:

Just as analysis is implicit in what the performer does, so every critical analysis is a more or less precise indication of how the work being analyzed should be performed. By explaining the processive and formal relationships of a composition, analysis suggests how phrases, progressions, rhythms, and higher-level structures should be shaped and articulated by the performer.4

To paraphrase and extrapolate from Meyer's words, reciprocation between analysis and performance takes place through a mutual understanding of the conventions of musical form and process; analysis implicit in performance evinces the performer's rational consideration of the design of a composition, from both small- and large-scale perspectives, while performance strategies implicit in the analyst's work reveal a sensitivity to the diachronic aspect of formal paradigms. This reciprocal view of analysis and performance may hold a measure of truth, but it is contradicted by real applications that expose underlying conflicts and tensions between the two activities and undermine any consistent reciprocity. This line of thought will be explored further later in the article.

The activities of analysts and performers also diverge from each other in notable ways. Performance, in the literal sense (that is, during the actual concert setting, disregarding for the moment the preparation for performance), is a diachronic process, unfolding in real time, while analysis, although carried out in time, is not limited in presentation by temporal duration or sequence. The analyst's interpretation is transmitted through primarily verbal and graphic means, while the performer's interpretation is transmitted aurally. The nature of both performance and analysis is such that each requires intense thought and intellectual consideration of possible alternatives to any interpretive decision, but performance includes an additional and separate physical component in that it also requires highly developed muscular actions and control, while analysis is essentially a rational pursuit of the mind. These analogies and disparities between the activities of analysis and performance bring into relief the complex and elusive nature of their relationship.

As mentioned earlier, analysis and performance are commonly understood to relate to each other didactically; the analyst, whose vocation itself involves explaining musical structures or phenomena, is placed in the role of informing the performer.5 Most musicians in all areas of specialization would surely acknowledge that the development of skills in formal and harmonic analysis as offered in undergraduate college or university curricula can be of great practical benefit to performers. Analysis, at the very least, provides a shared vocabulary of terminology in common usage to facilitate verbal discussion of musical works, and can provide a rational means for the performer to make interpretive decisions, thus contributing to a performer's understanding of musical structure in general terms. As a number of authors have remarked, a performer whose interpretation of a work is arrived at with the structural aspects of the piece in mind will be more satisfied with her or his performance decisions, and will be more likely to project the interpretation effectively. David Beach expresses this prevalent attitude succinctly:

. . . performance is based on knowledge, which is gained in part through the process of analysis. The more one knows about how a piece is put together, the greater the chance that the performance will be a convincing and accurate projection of the complex web of relationships inherent in its structure. It is the function of analysis to uncover these relationships.6

That performers can benefit from analysis of the works they perform is taken for granted, but this alone does not account for a relationship between analysis and performance. The relationship is not simple and direct, and resists straightforward definition. Beneath these common, though opposing, assumptions of service and parallelism lie a number of unanswered, and some unasked, questions about how analysis and performance relate to each other. This article is not intended to resolve these questions and issues, but, more modestly, to acknowledge them openly and to offer reflections upon some of them in an effort to come to a better understanding of the elusive nature of the relationship of analysis and performance.

Tensions between Analysis and Performance

Many performers are suspicious of analysis because of a perceived conflict between analysis as an arid intellectual preoccupation and their more immediate concerns with artistic inspiration, creativity, or intuition. I make this claim based on personal experience and discussion with performers, but documented corroboration can be found in Konrad Wolff's account of the teachings of pianist Artur Schnabel:

[Schnabel pointed out that] . . . Theoretical analysis as such is no cure-all . . . He always encouraged students to find out as much as possible about the structure, harmonies, motivic technique, etc. used in each score. But there is no basis for interpretation in most of this. Fruitful analysis is the result of spontaneous reaction to some musical detail which puzzles the musician so that he investigates what happens here in particular.7 [emphasis by Wolff]

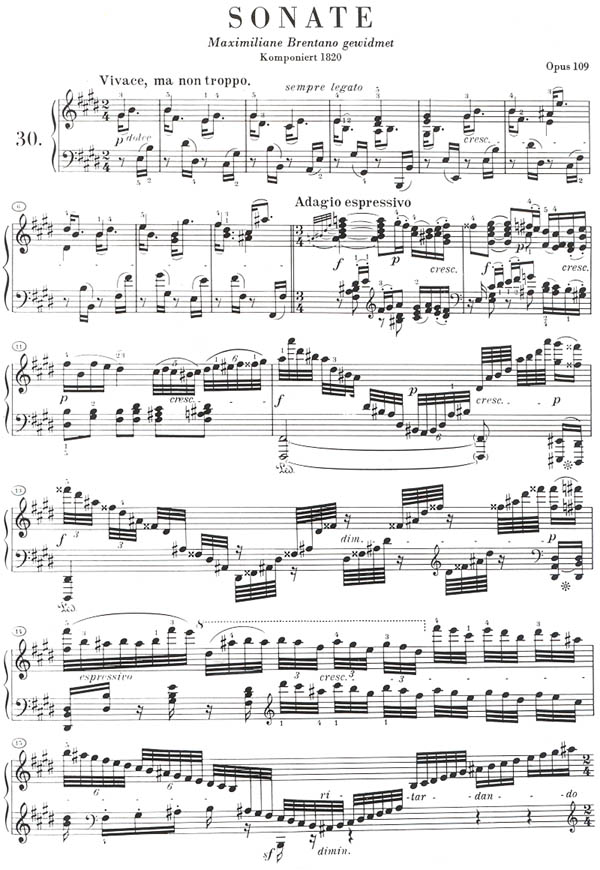

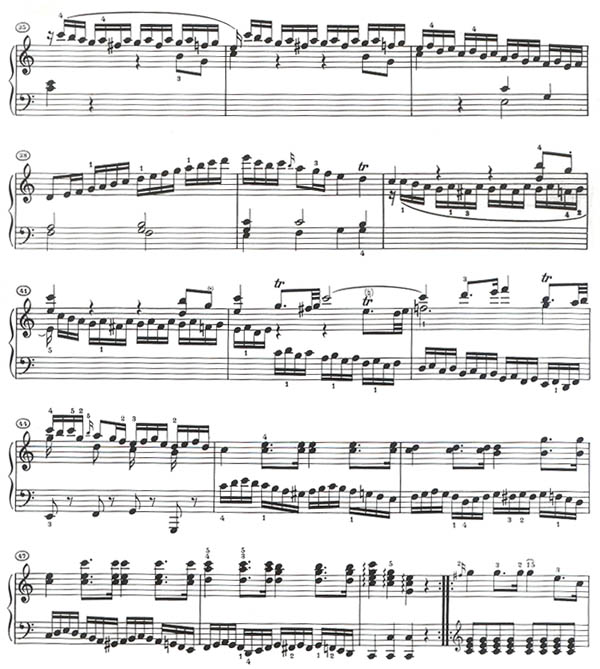

Schnabel's differentiation between theoretical and fruitful analysis suggests a degree of ambivalence about the role of analysis for the performer; analysis is encouraged, but for what purpose if there is "no basis for interpretation in most of this"? As an example of what Schnabel considered to be unproductive theoretical analysis, Wolff discusses the opening fifteen measures of Beethoven's Sonata Op.109, and his comments, cited below, reveal Schnabel's position on the role of analysis to a performer of this work. The score for these measures is reproduced in Example 1.

An academic outline analysis, as applied to the first movement of Beethoven's Sonata in E major, op.109, will establish the fact that the first eight bars constitute the first, the ensuing Adagio the second thematic group. If the pianist-interpreter lets himself be guided by this obvious fact, he will make an interruption after the first eight bars to bring out the formal contrast between the different themes and speeds. Nothing could be more wrong. There is one long line that goes from the first note to . . . [m.15] without stop or without a break of any kind. The initial E major chord opens a phrase which is continued until finally the E major key is replaced, in bar 15, by a B major chord implied in the sforzato bass on B. Schnabel formulated this as follows: "The question of form arises here only as one of the space to be conquered in one impulse, as inner necessity, as emotion put in motion, as something almost physical."8

EXAMPLE 1. Beethoven, Op. 109/I: mm. 1-15.

Reproduced from Beethoven, Klaviersonaten Band II, © 1980, with the kind permission of G. Henle Verlag, München.

Schnabel's academic or theoretical analysis reflects a particular mode of formal analysis, designating phrases or other formal units of a work by conventional terminology. This mode of analysis is essentially descriptive, not explanatory, and does not elicit any of the more interesting and dynamic features, such as voice leading, tonal structure and their interaction with design that may inform the work. A purely descriptive approach to analysis reveals no more, and possibly less, to an analyst than to a performer. (From a theorist's point of view, it is even questionable whether to regard such statements as analytical.) Schnabel does not disclose exactly what he understands by analysis that is fruitful, except to say that it supports or confirms what the performer already will have decided by musical instinct and sensitivity. He concedes that analysis can play a role in modifying a performer's instincts, but states clearly that he does not believe it has any role in producing the instincts in the first place.9

In the case at hand, the opening of Beethoven's Op.109, Schnabel (through Wolff) addresses perhaps the most fundamental issue that relates performance and analysis to each other: the segmentation of a whole into its constituent parts. For a performer, articulating the local disjunctions of smaller units while still projecting the coherence of a larger whole is a perpetual challenge, expressed eloquently by Schnabel's apprehension about losing the "long line" from mm.1-15 by overemphasizing on the disjunction between first and second theme groups at m.8. For the analyst, the selection of appropriate segments for informative analytical discussion is likewise challenging, another common touchstone linking the two activities.

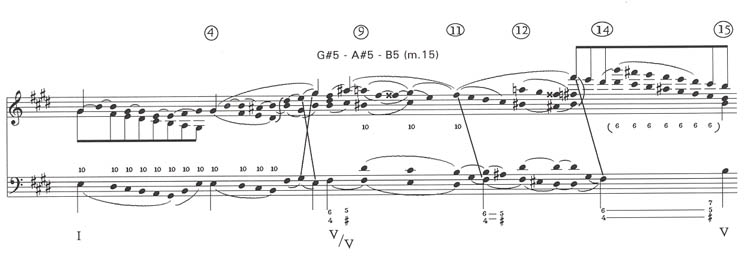

Schnabel's instincts about a "long line" extending from m.1 to m.15 can be substantiated analytically by a voice-leading graph showing the tonic harmony prolonged from m.1 to m.15, where it is supplanted at the middleground level by the dominant. (See Example 2a.)

EXAMPLE 2a. Beethoven, Op. 109/I: mm. 1-15, voice-leading graph.

Scale degree  , supported by tonic harmony, is initially prolonged through the inner-voice linear progression of an octave (

, supported by tonic harmony, is initially prolonged through the inner-voice linear progression of an octave ( 4-

4- 3) from mm.1-4, then through the register transfer from mm.4-7 (

3) from mm.1-4, then through the register transfer from mm.4-7 ( 4-

4- 5). At m.8,

5). At m.8,  5 ascends by step to

5 ascends by step to  5, which is supported by V of V. At the middleground, this

5, which is supported by V of V. At the middleground, this  5 is a passing tone whose goal is only reached in m.15, on B5, supported by V, precisely where Schnabel's (or Wolff's) intuitions had determined.10 This passing motion transcends all the changes in tempo and meter, as well as rhythmic and textural features at the surface that are introduced with the onset of the "adagio espressivo" at m.9. The prolongation of the middleground passing tone

5 is a passing tone whose goal is only reached in m.15, on B5, supported by V, precisely where Schnabel's (or Wolff's) intuitions had determined.10 This passing motion transcends all the changes in tempo and meter, as well as rhythmic and textural features at the surface that are introduced with the onset of the "adagio espressivo" at m.9. The prolongation of the middleground passing tone  5 is shown in some detail in Example 2a and summarized by the schematic reductions shown in Example 2b and 2c.

5 is shown in some detail in Example 2a and summarized by the schematic reductions shown in Example 2b and 2c.

EXAMPLE 2b, 2c.

Schnabel inferred that his analytical observations about the location of the first and second themes in Op.109/I would make an unmusical interpretation inevitable if a performer paid heed to them. Indeed, the simple identification of sectional units is sterile and does not, in itself, necessarily offer the performer great insights into interpretation. It need not, however, lead a performer to make the specific performance decision that Schnabel claims it will, and simple awareness of a formal division need not destroy the larger continuity of the entire exposition. The voice-leading graph as an analytical tool dynamically captures the essence of Schnabel's instincts about an unbroken structure from mm.1-15, but it offers more than just an assertion—certainly not an unfounded assertion, but one rooted in highly developed musical instincts—about the "long line": it also shows the means through which the prolongations at the middleground transcend the sectional divisions within a richly levelled foreground. One would hope that this mode of analysis—the voice-leading graph—might be deemed fruitful by Schnabel, as it serves to clarify his instinctive response to the piece more effectively than words alone can do. The singular impulse that Schnabel believed would be destroyed through conscious awareness of the point at which the second theme begins is reinforced as an integral component of the work.

It must be added that despite his admonishments against analysis, Wolff's book presents a rather analytical approach to teaching and interpretation on Schnabel's part. The contrast between Schnabel's strong statements quoted above and his analytical approach to such performance issues as whether dissonances should be played louder than their resolutions,11 or how meter relates to melody and harmony,12 as well as his familiarity with some of the writings of Schenker,13 suggest that despite his suspicions, his own musical instincts were not only confirmed by analytical study but also, to some extent, shaped by it.

A more recent book addressed to performers on interpretation of piano music by Kendall Taylor reveals an unabashedly positive attitude toward the benefits of analysis to the performer, while still acknowledging the apparent or perceived opposition between analysis and imagination.14 Taylor's view of the role of analyis for the performer concurs with the content of David Beach's statements quoted earlier, i.e., that the knowledge gained through analysis is indispensible for a performer. An additional concern expressed by Taylor, perhaps representative of many performers, is that analysis should assist the performer in grasping the intentions and motivations of the composer.

A detailed analysis can help the performer to grasp the inner logic and architecture of a composition, and it may lead him, with the help of intuition and informed imagination, to an understanding of the composer's vision. The value of analysis to the serious performer cannot be exaggerated. . . . The function of an analysis in depth would seem to be in some measure a reversal of the creative art (and science) of musical composition.15

Indeed, performers like Schnabel or Taylor, who have committed their ideas on interpretation to words, are driven towards rational insights and explanations that inevitably reveal the analytical bent of the author. Some, such as these two, offer insights into individual works that are often truly profound, arising from their intense familiarity with a vast repertoire, and probably do more to foster respect for the value of analysis among performers than do many of the authors of secondary literature in theoretical journals.

Analysis, either in relation to performance or in relation to composition, traditionally has been regarded as an activity that serves another activity perceived to be of a higher order. Music performance has a long history through many centuries and diverse social and iconographic contexts. Music analysis, by contrast, has a relatively short history as an independent activity, and even today many musicians outside of specialists in theory and analysis are unaware of this history. Many performers are taught to regard theory and analysis of music as primarily concerned with musical grammar and taxonomy. These are, of course, the basic materials that comprise the curricula for core undergraduate theory programs in most colleges and universities, and so are at the heart of most performers' shared experience in analysis. As important as the study of musical grammar and syntax is to the formation of a musician, and as appropriate as the theory classroom may be for acquiring this knowledge, music theory and analysis can and do aspire for more. Eugene Narmour writes:

Music theory . . . has a nobler goal than just teaching musicians how to acquire a knowledge of musical style or instructing them in the ways of reading music better. For the ultimate aim of any theory is not utilitarian or didactic but explanatory: good theories of music illuminate the various syntactic meanings inherent in a given musical relationship. They do not just classify musical materials for the practitioner's ease of consumption.16

Narmour's words bring into relief the tension between the performer's and theorist's understanding of the objectives of analysis. For the performer, analysis, as well as any other intellectual study of a work cannot help but be primarily concerned with practical and utilitarian matters, since there is an unequivocally more important goal (to the performer) to be achieved, and analysis is but one of several means to the end. For the analyst, analysis is an end, even a vocation, unto itself, or at least in tandem with music theory, and performance of a work analysed is unessential to the validity of the analysis. The underlying incompatibility between these positions is at the heart of the antipathy and alienation that exists between many performers and analysts.

Historical perspective on analysis and performance

Analysis and performance have not always been separated by the conceptual abyss that Schnabel's remarks quoted earlier reveal. Eighteenth-century figured bass and ornamentation practices constitute the prime example of a tradition in which analysis, by virtue of necessity, is integrated with, and indeed, inseparable from performance. In this context, analysis does not refer to analytical method but rather to the more general sense of conscious rational thought about music that is dependent upon theoretical knowledge for an effective performance. The continuo player realizing a figured bass relied on a degree of theoretical or analytical instruction to interpret individual figures and to understand specific voice-leading situations, special treatments of dissonant figures, and the rendering of melodic lines in the unnotated soprano and inner voices. The experienced continuo player would undoubtedly make appropriate decisions instinctively, but nevertheless depended upon prior training that was inherently analytical. Figured bass treatises were, on the whole, directed to the performing musician, but exhibited systematic and rational classification schema for figures, with rules for doublings, substitutions or possible additions for each figure. Thus, in addition to fulfilling their intended practical objectives, figured bass treatises also provided compendia of tonal simultaneities and voice-leading practices. A balance between continuo performance and analysis existed in which the performer who was equipped with the theoretical knowledge of figured bass made analytical decisions about local harmony in order to realize the figured bass, and conversely, the authors of figured bass treatises presented their theories with the practicing musician in mind. The performer was informed by prior analytical thinking and experience, not about specific pieces necessarily, but about music and music making in general.

The scope of certain figured bass treatises, notably those of C.P.E. Bach17 and Johann David Heinichen18 conspicuously extends beyond the needs of the performer to demonstrate the association of figured bass theory and composition, and consequently they amalgamate analysis and performance into a singular process within this tradition. Indeed, Heinichen's title reflects this compositional orientation explicitly. Among other things, his meticulous explanations of unusual treatments and resolutions of dissonance, particularly in the theatrical style, were undoubtedly of great interest to composers, and certainly not intended specifically for performers.19

The interdependence of performance and analysis in the figured bass tradition depended on the improvisatory aspect of continuo performance. Ex tempore performance required a knowledge of the structural framework for performance that could only be achieved through some degree of analytical understanding, perhaps internalized beyond the point of consciousness. As with figured bass realization, the same applies to improvised ornamentation. For example, Chapter XIII of Johann Quantz's famous treatise On Playing the Flute,20 entitled "Of Extempore Variations on Simple Intervals," includes over twenty-five simple melodic idioms and numerous illustrations of diminutions for each one, including arpeggiations, consonant skips, passing tones and rhythmic displacements. Examples such as these, which originated in performance practice, are invaluable as current pedagogical devices for illustrating the concept of melodic prolongation.21 They also indicate that the didactic aspect of the analysis-performance relationship need not be construed in one direction only, that is, from analysis to performance.22

Aside from the pragmatic subjects of figured bass and diminution, eighteenth-century treatises on other subjects—such as counterpoint, phrase structure, and form—were directed not to the performer but primarily to the composer, and the subject of analysis was largely the domain of the composer. With the decline of the improvisatory traditions, the role of analysis became conceived less in terms of interpretation of existing music and more in terms of inspiring the creation of new music through understanding classic formal models.23 In the twentieth century, this view of the role of analysis has been perpetuated by Arnold Schoenberg and his followers.24

Despite a small number of isolated analyses of single works from the nineteenth century that portend a wider view of analysis and a detachment of analysis from the concerns of composition, it is in the twentieth century that music analysis has evolved into an autonomous scholarly pursuit, an achievement that is largely due to Heinrich Schenker and his followers. As is well understood, Schenker strove to articulate the mechanisms of organic structure in the "masterworks" of the great tonal composers, and developed his theories over the course of his lifetime directly through his professional activities as a performer and editor.25 Perhaps the most unique feature of Schenker's theories is the absence of references to external models or theories; Schenker's theories provide a self-referential framework for analysis, in which the tonal structure of a work is defined hierarchically in its own terms. Such a theory elevates analysis of music from sterile parsing into a dynamic and creative act in which the analyst can become intimately aware of subtle and profound connections between both proximate and displaced events in a composition.

Schenkerian theory has had an enormous impact on theoretical and analytical scholarship, not only because of its own intrinsic value, but also by contributing to the impetus for the broader enterprise of developing new analytic methodologies that has preoccupied many theorists in the last half century or so. With the intellectual independence of musical analysis and the greater formalism that has entered the field of music theory in the second half of this century, the estrangement between analysts and performers is even more pronounced than in Schnabel's time, and threatens to persist.

Some Practical Illustrations

I will now turn to some practical illustrations drawn from well-known literature for solo piano (or keyboard), some of which have been the subject of discussion by other authors. The examples have been chosen in order to illustrate concisely three specific analytical issues that bear on the relationship between analysis and performance: hidden motivic connections between apparently contrasting themes; cadential elision and evasion; and motivic parallelisms. (These three issues pertain exclusively to tonal music, but the problems exposed are not necessarily restricted to a particular harmonic language.) The objective here is not to dictate how the music in question should be performed (though it is occasionally irresistible to make suggestions about how a passage should probably not be performed). The focus on these three issues will serve to underscore some of the complexities and contradictions involved in articulating the ambiguous relationship between analysis and performance.

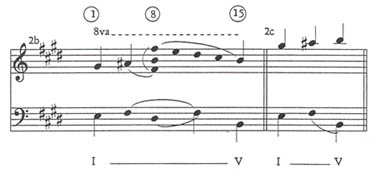

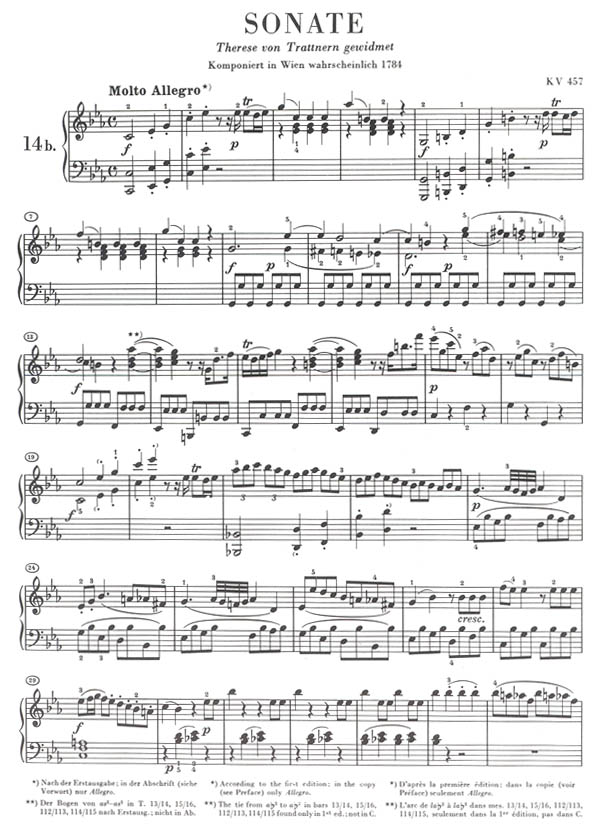

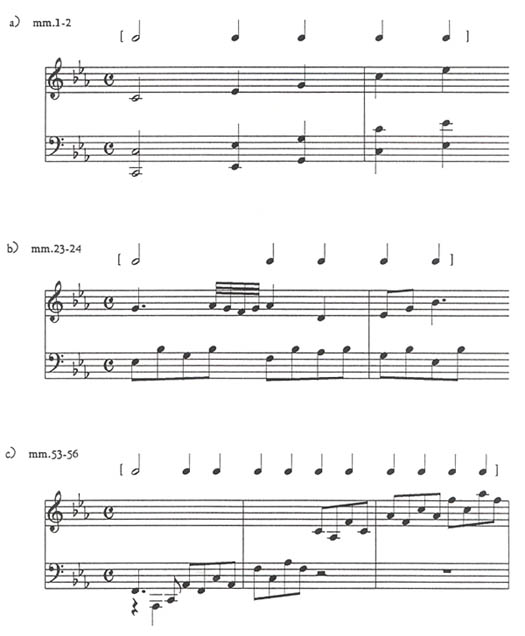

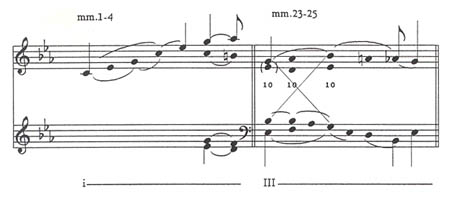

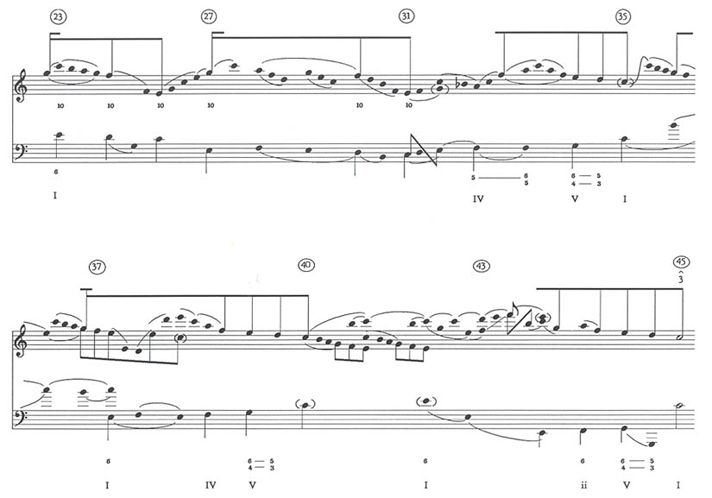

As a point of departure for discussion of the issue of hidden motivic connections between apparently contrasting themes, I will draw on a study by Roger Kamien, who points out underlying rhythmic congruities between the beginnings of the first theme and the second theme group (m.23) in the first movement of Mozart's Piano Sonata K.457.26 From this observation, Kamien suggests that the second theme be played in such a way as to bring out this connection with the work's opening gesture. (Example 3 contains the score for the opening of the movement. Example 4 shows the excerpts selected by Kamien and reproduces his rhythmic overlay.) He also includes another passage near the end of the second theme group (mm.53-56) that likewise refers to the opening in its underlying rhythmic/melodic profile, and suggests "slightly stressing the underlying quarter-note rhythmic pattern," again to draw out the connection to the first theme.27 Notwithstanding these suggestions to convey the rhythmic connections in performance, Kamien begins his article with an elegant disclaimer stating that specific analytical observations cannot lead to a specific performance strategy. He writes:

. . . the connection between analysis and performance is very complex. Analysis reveals and clarifies the multiplicity of relationships that govern a musical work. But a specific musical relationship can be projected in a variety of ways. . . Some relationships in a composition may not even require any special emphasis. The performer must choose—either consciously or unconsciously—which of the relationships are to be brought out.28

EXAMPLE 3. Mozart, K. 457/I: mm. 1-35.

Reproduced from Mozart, Klaviersonaten, © 1977, with the kind permission of G. Henle Verlag, München.

EXAMPLE 4. Mozart K. 457/I: excerpts with Kamien's rhythmic overlay.

By disregarding his own admonition, and proceeding to suggest a performance strategy for bringing out the motivic connection between mm.53-56 and the opening, Kamien reveals what is probably an irresistible urge for many performers who use analysis in preparing their interpretations—to account for their personal performance decisions, not necessarily with the intent to be prescriptive towards other performers who may not play the passage in the same way. In spite of his hortatory tone, Kamien's recommendation for a slight stress on the quarter notes in mm.53-56 need not invite other performers to do exactly the same. I would submit that Kamien's observations regarding mm.53-56 and the opening should not require "any special emphasis" to bring out, as the metric organization alone will provide the necessary weight to enunciate the quarter notes and the connection to the opening. To add any stress to the quarter-note beats could risk sounding unmusical in performance, and diminish the effect on the listener by destroying its subtlety.

Returning to the rhythmic similarities between mm.1-2 and mm.23-24, voice-leading graphs of these brief passages reveal fundamentally different contexts. (See Example 5.)

EXAMPLE 5. Mozart, K. 457/I: mm. 1-4 and mm. 23-25, voice-leading graphs.

The graph of mm.1-4 shows two arpeggiations of the tonic triad, one at the foreground level and one at the middleground. The former articulates the motion from  to

to  (C4 to

(C4 to  5 within a larger arpeggiation that constitutes the initial ascent to the entry of the primary tone

5 within a larger arpeggiation that constitutes the initial ascent to the entry of the primary tone  , G5, which arrives in m.3. The graph of mm.23-25 shows an entirely different voice-leading event, a linear progression from G4 to

, G5, which arrives in m.3. The graph of mm.23-25 shows an entirely different voice-leading event, a linear progression from G4 to  4, which serves to prolong G4. The linear progression is supported by the parallel tenths between the outer voices and a voice exchange between the alto and bass, prolonging the mediant harmony.

4, which serves to prolong G4. The linear progression is supported by the parallel tenths between the outer voices and a voice exchange between the alto and bass, prolonging the mediant harmony.

One can certainly identify a rhythmic and metric coincidence between the locations of middleground events just described in the two passages. As Kamien points out, the melodic goal of the foreground arpeggiation,  5, arrives on the second beat of m.2, just as the apex of the linear progression in parallel tenths,

5, arrives on the second beat of m.2, just as the apex of the linear progression in parallel tenths,  4, arrives on the second beat of m.24. But the nature of the underlying melodic and harmonic prolongations and the contrapuntal implications are not parallel. The

4, arrives on the second beat of m.24. But the nature of the underlying melodic and harmonic prolongations and the contrapuntal implications are not parallel. The  5 in m.2 and the

5 in m.2 and the  4 in m.24 are both subservient to the more extensive voice-leading motions described above. In melodic terms, the arpeggiation in mm.1-3 connects three distinct pitches, while the passage from mm.23-25 prolongs a single pitch, G4. Furthermore, the melodic gestures in each of these passages contrast starkly in terms of register—mm.1-3 spanning an octave and a half, mm.23-25 spanning a third. The distinctly different voice leading in each passage overrides the more superficial rhythmic similarities, and therefore the articulation of the arpeggiated tonic triad in mainly quarter note values in mm.1-3 should not be uncritically adopted as a model for the articulation of the passage from mm.23-25, as Kamien suggests. To be sure, the rhythmic connections pointed out by Kamien may constitute valid observations about underlying threads that contribute to the unity of the work, and awareness of these connections would surely contribute to a performer's appreciation of the work's intricacies. However, it is shortsighted to translate such observations facilely into specific directions to stress the rhythmic correspondences in performance, and is likely to be perceived as mechanical and counter-intuitive to many performers, not to mention listeners.

4 in m.24 are both subservient to the more extensive voice-leading motions described above. In melodic terms, the arpeggiation in mm.1-3 connects three distinct pitches, while the passage from mm.23-25 prolongs a single pitch, G4. Furthermore, the melodic gestures in each of these passages contrast starkly in terms of register—mm.1-3 spanning an octave and a half, mm.23-25 spanning a third. The distinctly different voice leading in each passage overrides the more superficial rhythmic similarities, and therefore the articulation of the arpeggiated tonic triad in mainly quarter note values in mm.1-3 should not be uncritically adopted as a model for the articulation of the passage from mm.23-25, as Kamien suggests. To be sure, the rhythmic connections pointed out by Kamien may constitute valid observations about underlying threads that contribute to the unity of the work, and awareness of these connections would surely contribute to a performer's appreciation of the work's intricacies. However, it is shortsighted to translate such observations facilely into specific directions to stress the rhythmic correspondences in performance, and is likely to be perceived as mechanical and counter-intuitive to many performers, not to mention listeners.

As Kamien intimates in the quotation above, some aspects of tonal structure are so elemental and self-referential that they should require no special emphasis or performance strategy to bring out. For example, model cadences that demarcate significant points of closure and partial closure in a work often need no special articulation, because their intrinsic structural properties define their function. In normative antecedent and consequent phrase pairings, the half cadence at the end of the antecedent phrase creates an incomplete harmonic motion that is completed by the arrival of the authentic cadence at the end of the consequent phrase. The experienced performer's familiarity with conventions of tonal rhetoric may make analytical classification of such situations seem redundant for the purpose of performance.

Not all cadences, of course, are so clearly defined in terms of their function. Two potentially ambivalent cadential situations are the elided cadence and the evaded cadence. In each of these, the conflicting functions of closure and beginning coincide at the same moment, and suggest the need for conscious deliberation by the performer in choosing which function to emphasize or planning an effective strategy for projection of both functions.

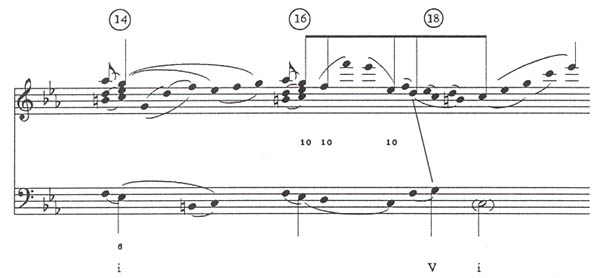

An example of an elided cadence occurs at the close of the first theme of the first movement of the sonata K.457/I by Mozart. (The score for this passage appears in Example 3.) The transition begins at m.19 with a restatement of the strident opening gesture of the work (minus the low bass reinforcement), and the C5 in m.19 functions simultaneously as the melodic closure on  of the first theme. Example 6 shows a voice-leading graph of the passage.

of the first theme. Example 6 shows a voice-leading graph of the passage.

EXAMPLE 6. Mozart, K. 457/I: mm. 14-19, voice-leading graph.

In a situation such as this, the performer may consider the dual role of the downbeat of m.19 in providing closure to the first theme and announcing the beginning of the next formal unit. The voice-leading graph shows the embellishment of the primary tone G5 with its upper neighbor  5 and the subsequent stepwise descent down to C5.29 This descent—a linear progression that replicates the fundamental line at the middleground—and its harmonic support provide the expected tonal closure to the first theme. The harmonic support for

5 and the subsequent stepwise descent down to C5.29 This descent—a linear progression that replicates the fundamental line at the middleground—and its harmonic support provide the expected tonal closure to the first theme. The harmonic support for  at the conclusion of the linear progression, however, is not literally present but implied, underlying the formal ambiguity of this moment.

at the conclusion of the linear progression, however, is not literally present but implied, underlying the formal ambiguity of this moment.

Although the voice leading clearly signifies harmonic and melodic closure by its goal-directedness to C5 at m.19, certain surface-level features at the arrival of C5 identify its simultaneous role in beginning the transition. The abrupt change in dynamic level from piano to forte suggests that priority when this moment arrives should go to projecting the restatement of the opening gesture. The absence of bass support in the appropriate register also suggests a relinquishment of the function of closure in favor of that of beginning. This evidence suggests that introducing the transition should be regarded as the primary role of the downbeat of m.19; in view of the temporal nature of the medium of performance, what is imminent, what is taking place at this moment or just about to take place, will generally be of utmost importance. The prior linear progression from G5 to C5 carries its own distinct implications, which can be conveyed and perceived even if they are weakened at the point of closure to allow the elision with the transition. The voice leading indicates a ranking of the dual functions of closure and beginning, with that of beginning taking precedence on the downbeat of m.19 in a performance situation. Up to that point, the momentum of the linear progression toward melodic and harmonic closure on the tonic can be projected. Exactly how to project this momentum while also projecting the obstruction of actual closure in favor of the new beginning—be it through a slight pause before C5, or a slight lengthening of its duration, or through other means—is an artistic decision that can only be made by the performer. Such moments in a performance can be most dramatic because of the conflict of implications and thwarted expectations, and can be exploited effectively by the performer.

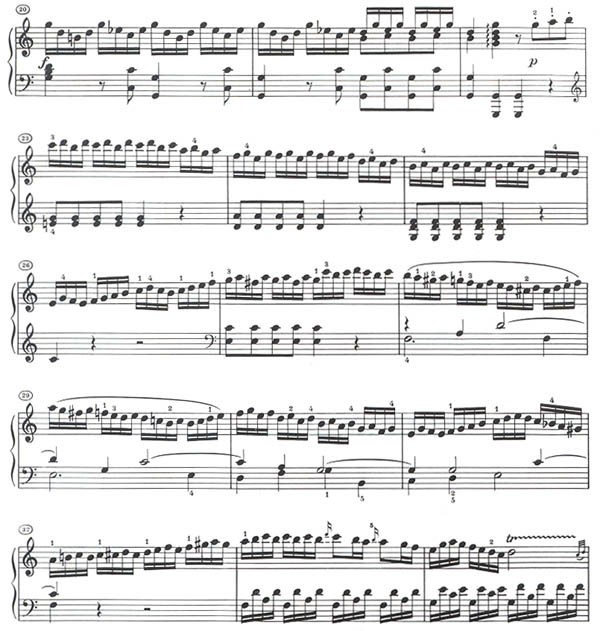

Cadential evasion is closely related to cadential elision, but in evaded cadences the function of closure is in conflict not with that of beginning, but with that of continuation. As an example, I have chosen the second theme group of Mozart's Piano Sonata K.310, mm.23-45, the score for which is given in Example 7.

EXAMPLE 7. Mozart, K. 310/I: mm. 20-50.

Reproduced from Mozart, Klaviersonaten, © 1977, with the kind permission of G. Henle Verlag, München.

In this excerpt, cadential evasion, a prominent feature of second themes in the classical sonata repertoire,30 dramatically defers the arrival of full melodic and harmonic closure at the end of two linear progressions from G5 to C5, supported by a cadential progression in the secondary key area of C major. (See the voice-leading graph in Example 8.)31

EXAMPLE 8. Mozart, K. 310/I: mm. 23-45, voice-leading graph.

The first of the linear progressions extends from mm.23-35; G5 is initially prolonged by two subsidiary third progressions, each supported by a linear intervallic pattern in parallel tenths. The melodic descent toward C5 begins in m.32 and concludes in m.35, but with an implied, rather than an actual C5. The absence of melodic closure here because of the missing C5 launches the next attempt at closure through another statement of the fifth-progression (G5-C5) from m.35 to m.40, but this time there is no harmonic closure. The bass note C4 supporting  is shown on the graph as an implied note. In each of these linear progressions closure is attempted, but then thwarted by dramatic shifts in the register of the implied melodic or bass note.

is shown on the graph as an implied note. In each of these linear progressions closure is attempted, but then thwarted by dramatic shifts in the register of the implied melodic or bass note.

The passage in mm.40-45 begins by presenting the material from mm.35-40 in freely invertible counterpoint, prolonging C6 as a cover tone above the G5 which begins its final linear progression to C5 in m.44, and concludes with both melodic and harmonic support in m.45.32 A performer who is aware of the dramatic potential in these successive frustrated attempts at closure will be able to shape the entire second theme group in a way that not only sustains the dramatic tension, but also intensifies it. David Beach illuminates this strategy:

This lack of closure in bar 35 and again in bar 40 has direct implications for performance. Quite obviously one must play through the intermediary cadences until the goal is achieved. That is, the performer must not allow the tension to release prematurely, but must carry the momentum through these points to the end.33

A performer with strong musical intuitions and experience with music of the classical repertoire may well respond to an analytical discussion such as the preceding examination of the second theme group of K.310/I by claiming that the performance strategy proposed—drawing out the dramatic potential in the passage by "playing through" the evaded (Beach's "intermediary") cadences—is obvious and instinctively well understood.34 As much as the practical value of formal analysis is widely acknowledged among performers, the advice to "play through" the evaded cadences in an example such as this is a conclusion that a sensitive pianist would be likely to arrive at intuitively without the more technical approach of the analysis. Such a tight correspondence between a conclusion arrived at independently through the performer's insight and the analysts's more protracted study, here and also in the case of the opening of Beethoven's Op.109 sonata discussed earlier, demonstrates the inadequacy of conceptualizing the relationship between analysis and performance simply in terms of how analysis can benefit the performer.

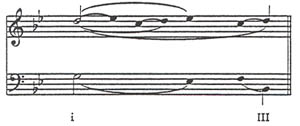

Influenced by Schenkerian theory, analysts of tonal music are often drawn to parallel recurrences of important tonal motives at the foreground and middleground. Consider, as a simple illustration, the beginning of the passacaglia theme from Handel's Seventh Suite for harpsichord, shown in Example 9.

EXAMPLE 9. Handel, Suite VII, Passacaille, mm. 1-2: score and voice-leading graph.

Reproduced from Handel, Klaviersuiten, © 1983, with the kind permission of G. Henle Verlag, München.

The foreground double neighbor figure D5- 5-C5-D5 is replicated at the middleground, as the voice-leading graph shows. The middleground double neighbor prolongs D5 (scale degree

5-C5-D5 is replicated at the middleground, as the voice-leading graph shows. The middleground double neighbor prolongs D5 (scale degree  ) as its harmonic support changes from tonic to mediant. As Schenker has demonstrated, such motivic parallelisms are common in tonal music, and are most satisfying to discover (at least for those of us with a passion for analyzing music), but of all the issues raised in this essay, this is perhaps the most troubling to assess in terms of implications for performance. The concept of motivic parallelisms engages at once both the synchronic aspect of analysis and the diachronic aspect of performance. In this excerpt, the enlarged replication of the double neighbor figure is analytically significant because of the interaction of the motivic and harmonic processes, but the performer would probably be reluctant to allocate any special emphasis or stress on the D5 in m.2 because it would detract from the momentum of the harmonic sequence.

) as its harmonic support changes from tonic to mediant. As Schenker has demonstrated, such motivic parallelisms are common in tonal music, and are most satisfying to discover (at least for those of us with a passion for analyzing music), but of all the issues raised in this essay, this is perhaps the most troubling to assess in terms of implications for performance. The concept of motivic parallelisms engages at once both the synchronic aspect of analysis and the diachronic aspect of performance. In this excerpt, the enlarged replication of the double neighbor figure is analytically significant because of the interaction of the motivic and harmonic processes, but the performer would probably be reluctant to allocate any special emphasis or stress on the D5 in m.2 because it would detract from the momentum of the harmonic sequence.

Should a performer strive to bring out such motivic parallelisms? Theorists who have broached this question are equivocal. Wallace Berry addresses the issue in regard to the Adagio introduction to the first movement of Beethoven's 4th Symphony, in which the motive of a descending third  -

- pervades the musical surface at the foreground and also informs the middleground in the first five measures.35 Berry's advice to a conductor concerning the middleground third-motive is to carefully articulate the foreground occurrences of the motive, which will enable the parallelism with the middleground to emerge. He has no specific advice concerning how, in fact, to perform the middleground motive. Charles Burkhart endorses a direct performance strategy to bring out a motivic parallelism in an example from the third movement of Beethoven's Sonata Op.7, but he also recognizes that too conspicuous an effort to bring out a motivic parallelism may violate the integrity of the piece.36 Janet Schmalfeldt offers quite specific advice for bringing out a concealed motivic parallelism, but is criticized on this point by John Rink because of the disruption that would occur in connecting non-contiguous notes that fall on strong and weak metric positions.37

pervades the musical surface at the foreground and also informs the middleground in the first five measures.35 Berry's advice to a conductor concerning the middleground third-motive is to carefully articulate the foreground occurrences of the motive, which will enable the parallelism with the middleground to emerge. He has no specific advice concerning how, in fact, to perform the middleground motive. Charles Burkhart endorses a direct performance strategy to bring out a motivic parallelism in an example from the third movement of Beethoven's Sonata Op.7, but he also recognizes that too conspicuous an effort to bring out a motivic parallelism may violate the integrity of the piece.36 Janet Schmalfeldt offers quite specific advice for bringing out a concealed motivic parallelism, but is criticized on this point by John Rink because of the disruption that would occur in connecting non-contiguous notes that fall on strong and weak metric positions.37

The concept of motivic parallelism is one that depends on specialized study of Schenkerian analytical techniques and the theory of structural levels, precluding its full appreciation by a performer without exposure to such specialized study. To this performer, the concept seems esoteric and not of direct concern. By its very nature as an analytical construct revealing large-scale connections between non-contiguous notes, and by its forward and retroactive references, motivic parallelism is detached from the linear temporal domain that is essential to performance. The question of whether such parallelisms can be perceived is one that applies more to a listener than the performer; a listener who can hear, or will herself or himself to hear, motivic parallelisms and other relationships between discrete structural levels is not dependent on the performer's effort to bring out these phenomena.

The three issues considered in this section—hidden motivic connections between apparently contrasting themes, cadential evasion and elision, and motivic parallelism—were selected to illustrate that some recommendations for interpretation that may be perceived as counter-intuitive, obvious, or esoteric may emanate from analysis, even when the analysis is inherently convincing and insightful. This is not to denigrate the seriously conceived work of authors mentioned, but to suggest that herein lies the source of at least some of the discomfiture among performers who view such recommendations by analysts as driven more toward justifying the analysis and projecting the discoveries of the analyst than illuminating the performer.

Conclusion

The ambivalence expressed in these reflections on the relationship of analysis and performance is partially attributable to the numerous and varying connotations of the term analysis. Specialists not only in music theory, but also in the disciplines of musicology, education, and other subdisciplines, as well as performance, study musical compositions and therefore make analytical observations. Analysis may be used to assist in dating works, or to classify them by genre, style, or other criteria; it does not necessarily always involve consideration of the structure of musical compositions. To a theorist, analysis can involve structural aspects of entire compositions (even entire repertoires) or can be limited to excerpts of varying lengths; it can refer variously to the formal function of passages of differing lengths, to the interpretation of the voice-leading function of individual harmonies, to local or to large-scale events; it may be restricted to relationships that center on pitch or tonal organization, or may include other parameters, such as register, articulation, instrumentation or rhythm, or may combine these in particular ways; it may reflect an existing theoretical model, or it may be utilized to demonstrate a new model. To a specialist in analysis or theory, these divergent modes of analysis will be understood, but to some performers, some of the more abstract ones may be unfamiliar and/or even distasteful, as reflected in the remarks cited earlier by Schnabel.

A number of authors have written about a relationship between analysis and performance, but there has been little research tradition or serious scholarly dialogue with any true comparison or exchange of ideas on the subject. A recent exception is John Rink's review of Wallace Berry's book, Musical Structure and Performance, which he begins by surveying some of the growing literature purporting a relationship between analysis and performance.38 Rink points out that the relationship is defined in quite different terms by different authors, resulting in a large amount of confusion and contradiction.39 The incompatibilities result, in large measure, from the differing orientations to the nature and goals of analysis on the parts of authors who are primarily theorists.

As I have said, a conspicuous inclination of authors writing about the relationship of analysis and performance is to link analysis and performance causally, citing ways in which specific analytical findings lead to specific performance directives, such as a certain note or chord should be accentuated or "brought out" in some way, or that certain dynamic treatment is intimated for a given passage.40 Wallace Berry goes so far as to state that every analytical observation has an implication for performance, adding that the implication may be one of neutrality.41 Janet Schmalfeldt expresses the more flexible attitude that more than one approach to interpretation can be adduced from a single analytical observation;42 analysis may suggest what should be brought out, but not in itself how to do it. Jonathan Dunsby states that ". . . the most helpful way to characterize analysis for the performer . . . is not as some form of absolute good, but as a problem-solving activity."43 This interaction between analysis and performance is by nature selective, in that what the analyst and the performer perceive as problems may differ considerably.

Two authors who have advocated the development of a new mode of analysis emanating specifically from the performer's concerns are John Rink and Tim Howell. John Rink appeals for an approach to analysis based on "informed intuition," an approach that would offer more practical assistance or benefit to the performer than existing modes of analysis.44 Tim Howell recommends the synthesis or amalgam of various analytical approaches as initiated by the instinctive reactions of the performer. A mode of analysis that could actively engage performers would undoubtedly be valuable, and an analytical approach based on "informed intuition" could even benefit theorists by strengthening their ties to the larger musical community and elevating their perceived role beyond that of teachers of musical grammar. This conception, however, would likely be distasteful and even alienating for the analyst, who would likely find it capricious. The most serious difficulty with implementing such a mode of analysis would be in resolving the respective exigencies of each group: the analyst's need for rigor and the performer's need for a place for intuition. And yet these exigencies are not mutually exclusive, but complementary. For many analysts, the process of analysis begins with an intuitive idea or a response to a musical work, and for many performers, the process begins with rigorous working out of technical difficulties and simply "learning the notes." The attributes of intuition and rigor belong to both analysis and performance, though not necessarily at the same stage in the process for each.45

A basic issue left unaddressed by most authors subscribing to the didactic benefits of analysis to performers is that of who is the producer of the analysis. Analyses by those who are specialists in theory and analysis are often presented in technical language and graphic means that, at least within current educational systems in North America, require specialized training only rarely assumed to the same level by performers. The analysis is then not undertaken, but responded to, by the performer.46 The interested performer will, naturally, study analysis to a certain point, but the compulsion for specialization, which enters into college curricula at an early stage, prevents most young performers from learning the skills needed to accomplish independently analyses that transcend the descriptive. The same interested and gifted performer may be able to glean a great deal from clearly conceived and presented analytical commentary and lucid graphs by a specialist in theory or analysis, and gain insights into the music that may well influence a performance, but formulating one's own analysis and responding, even thoughtfully, to someone else's are not the same thing. These circumstances reverberate with pedagogical implications involving not only the analytical techniques that are taught at the undergraduate level, but also the role of analysis among musicians of various specializations.

It is at the level of process—the process of discovery and preparation of a committed interpretation, even if subject to change—that the ontological connection between analysis and performance emerges. Although there are profound differences between the cognitive processes involved in these two activities, and conflicting ways in which to comprehend the potential influence of either one on the other, I find myself still struck by the three basic analogies outlined at the beginning of this article: the point of departure from the written score; the combination of intuition and acquired knowledge or skills; and the attempt to arrive at and convey a convincing personal interpretation of a living work of art. These powerful ontological links between the activities of performance and analysis undermine the pragmatic bias that is prevalent in the literature, and they indicate, ironically, that the conceptual independence of analysis yields the basis of their connection. At the same time, these fundamental bonds suggest that more can and should be done through research and pedagogy to amplify the points of contact between analysis and performance, and to capitalize on their symbiosis, perhaps through some format of a collaborative nature that draws on the vocational expertise of both analysts and performers. Such a format would induce greater interaction between performing and scholarly musicians as colleagues, and assuage the deleterious effects of the antipathy that exists between them. The intimacy with exquisite works of art that is attainable, through different means, in both performance and analysis is the essence of their connection. A rapprochement between performers and analysts that includes a sharing of insights gained through intimate knowledge, and a deeper commitment to learn from each other, can only lead to deeper analytical insights and more illuminating performances.

1A preliminary version of this article was prepared for the Special Theory Colloquium at the Canadian University Music Society annual meeting in Ottawa, Ontario, May 1993. I wish to express my appreciation to Richard S. Parks, who acted as respondent to that paper (and two others) at the "Analysis and Performance Relationships" session; points raised by Parks in his thoughtful response undoubtedly influenced the version presented here. Thanks are also due to pianist Joachim Segger of Edmonton, Alberta, for his comments on two earlier drafts of this article and for engaging in an extended and often provocative dialogue on the relationship of analysis and performance.

2This account of the motivation of analysts and performers to choose individual works for study is, admittedly, oversimplified. Other more pragmatic motivations for performers may include available performing resources or considerations of balance in concert programming. An analyst may be motivated by theoretical factors that point to certain repertoires or even specific pieces, as well as pragmatic factors pertaining to available resources, such as scores, or the exigencies of teaching.

3Although most of the secondary literature on this topic implicitly or explicitly addresses the question of how analysis can benefit performers, a stimulating and compelling essay by Joel Lester approaches the analysis/performance relationship conversely, exploring ways in which different performance interpretations can influence analytical interpretations. See Joel Lester, "Interactions Between Analysis and Performance," in Performance Studies, ed. John Rink (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, forthcoming). A version of this article was presented at the Fifth British Music Analysis Conference in Southampton, UK, in March 1993.

4Leonard B. Meyer, Explaining Music (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1973), 29.

5Those whose vocation is to explain musical structures are more properly referred to, of course, as theorists, not analysts. The two monikers may often apply to the same individual, but the concerns of theory and analysis differ significantly, a subject too extensive to explore in the present context. References to the "analyst" in this article will be generic, and will include the possibility for interpretation as theorist.

6David Beach, "The First Movement of Mozart's Piano Sonata in A Minor, K.310: Some Thoughts on Structure and Performance," Journal of Musicological Research 7 (1987): 157.

7Konrad Wolff, Schnabel's Interpretation of Piano Music, with a new preface by Alfred Brendel (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1979), 18-19. First edition published under the title The Teaching of Artur Schnabel (London: Faber and Faber, 1972).

8Ibid., 19.

9Ibid., 20.

10This reading diverges somewhat from an orthodox Schenkerian reading of the passage, which would place the structural arrival on  , supported by V, at m.11. (See Heinrich Schenker, Free Composition, [New York: Longman, 1979], 138.) The analysis presented here evinces a covering progression (

, supported by V, at m.11. (See Heinrich Schenker, Free Composition, [New York: Longman, 1979], 138.) The analysis presented here evinces a covering progression ( 5-

5- 5-B5) at the middleground, situated registrally above the arrival on

5-B5) at the middleground, situated registrally above the arrival on  . While not conflicting substantially with the harmonic-contrapuntal framework of the orthodox reading, aside from the interpretation of

. While not conflicting substantially with the harmonic-contrapuntal framework of the orthodox reading, aside from the interpretation of  5 as an expanded passing tone, this reading draws out the dynamic quality of the anticipated arrival on V, which is not conclusive until m.15. It accomplishes this through the registral connection from the initially prolonged

5 as an expanded passing tone, this reading draws out the dynamic quality of the anticipated arrival on V, which is not conclusive until m.15. It accomplishes this through the registral connection from the initially prolonged  5 through

5 through  5 in m.9 to B5 in m.15, creating a "long line" that is perhaps more concretely perceptible than the orthodox background paradigm of a sonata exposition.

5 in m.9 to B5 in m.15, creating a "long line" that is perhaps more concretely perceptible than the orthodox background paradigm of a sonata exposition.

11Ibid., 46-48.

12Ibid., 56-72.

13Ibid., 64, 123, 128.

14Kendall Taylor, Principles of Piano Technique and Interpretation (Borough Green, Sevenoaks, Kent: Novello, Inc., 1981), particularly Chapter V, "Analysis and Imagination."

15Ibid, 118.

16Eugene Narmour, "On the Relationship of Analytical Theory to Performance and Interpretation," in Explorations in Music, The Arts and Ideas, ed. Eugene Narmour and Ruth Solie (Stuyvesant, NY: Pendragon Press, 1988), 317.

17C.P.E. Bach, Versuch über die wahre Art das Clavier zu spielen (Berlin: 1759-1762). See also Essay on the True Art of Playing Keyboard Instruments, tr. and ed. William J. Mitchell (New York: Norton, 1949).

18Johann David Heinichen, Der General-Bass in der Composition (Freiburg: Christoph Mattheus, 1728). Facsimile edition (Hildesheim: Georg Olms, 1969).

19See George Buelow, "Heinichen's Treatment of Dissonance," Journal of Music Theory 6 (1962): 216-73.

20Johann Joachim Quantz, On Playing the Flute, tr. and ed. Edward R. Reilly (New York: Schirmer Books, 1966), 136-61.

21See Allen Forte and Stephen Gilbert, Introduction to Schenkerian Analysis (New York and London: Norton, 1982), 7-9.

22Stephen Hefling writes about performance practice and structural levels as represented in Quantz's treatise in "'Of the Manner of Playing the Adagio': Structural Levels and Performance Practice in Quantz's Versuch," Journal of Music Theory 31 (1987): 205-23.

23For a fuller discussion of the history of music analysis, see Jonathan Dunsby and Arnold Whittall, Music Analysis in Theory and Practice (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988), 11-19. See also Ian Bent, Analysis (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1987), 1-78.

24Arnold Schoenberg, The Fundamentals of Musical Composition (London: Faber & Faber, 1970). See also Erwin Ratz, Einführung in die musikalische Formenlehre, dritte erweiterte und neugestaltete Ausgabe (Wien: Universal Edition, 1973).

25For a splendid account of Schenker's views on performance, see William Rothstein, "Heinrich Schenker as an Interpreter of Beethoven's Piano Sonatas," 19th Century Music 7 (1984): 3-28. Rothstein focuses on several unpublished sources in the Oswald Jonas Memorial Collection at the University of California at Riverside.

26Roger Kamien, "Analysis and Performance: Some Preliminary Observations," Israel Journal of Musicology 3 (1983): 156-70.

27Ibid., 164.

28Ibid., 157.

29Note the motivic connection between the upper neighbor as a prefix to  in m.13 and m.15, and its appearance as a suffix in m.4 at the initial entry of the primary tone.

in m.13 and m.15, and its appearance as a suffix in m.4 at the initial entry of the primary tone.

30For a comprehensive treatment of cadential evasion as a characteristic device in eighteenth-century second theme groups, see Janet Schmalfeldt, "Cadential Processes: The Evaded Cadence and the 'One More Time Technique,'" Journal of Musicological Research 12 (1992): 1-52. See also William Caplin, "The Expanded Cadential Progression: A Category for the Analysis of Musical Form," Journal of Musicological Research 7 (1987): 215-58.

31I am indebted to David Beach's detailed article on this movement, which provides voice-leading graphs of virtually the entire movement. My graph of the passage conforms quite closely in interpretation to Beach's, differing mainly in matters of notation and a greater amount of detail from mm.40-45. Beach offers additional insights into the hypermetric organization of the second theme group. See Beach, "The First Movement of Mozart's Piano Sonata in A Minor, K.310," 165-67.

32It could be argued that harmonic closure is not achieved even at m.45 because of the disruptive registral shift of two-and-a-half octaves in the bass from the cadential dominant to tonic harmonies, but only at m.49, the final measure of the exposition.

33Beach, "The First Movement of Mozart's Piano Sonata in A Minor, K.310," 166.

34Beach's suggestion to "play through" the evaded cadences is not so much a recommendation toward a specific action, rather, an exhortation not to destroy the longer-range directedness toward the real harmonic goal in m.45.

35Wallace Berry, Musical Structure and Performance (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1989), 19.

36Charles Burkhart, "Schenker's Theory of Levels and Musical Performance," in Aspects of Schenkerian Theory, ed. David Beach (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1983), 99-105.

37Janet Schmalfeldt, "On the Relation of Analysis to Performance: Beethoven's Bagatelles Op.126, Nos. 2 and 5," Journal of Music Theory 29 (1985): 12, 18. John Rink points out Schmalfeldt's equivocalness between bringing out the concealed motivic repetition and maintaining its concealed identity, as well as the questionable results in performance from undue stress on non-contiguous notes in the effort to bring out their middleground contiguity. See John Rink, review of Musical Structure and Performance, by Wallace Berry, Music Analysis 9 (1990): 320-21.

38Rink, review of Musical Structure and Performance by Wallace Berry, 319-39.

39Ibid., 319-24.

40Rink provides several good illustrations of this found in writings by Janet Schmalfeldt, Wallace Berry, Leonard Meyer and Eugene Narmour.

41Wallace Berry, Musical Structure and Performance (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1989), 44. "Every analytical finding has an implication for performance, even when it suggests a relatively neutral execution that projects explicit, self-evident factors of structure."

42Schmalfeldt, "On the Relation of Analysis to Performance", 28.

43Jonathan Dunsby, "Guest Editorial: Performance and Analysis of Music," Music Analysis 8 (1989): 8. Dunsby connects the "interaction of pedagogy and performance" with the history of nineteenth- and twentieth-century editorial practice, at least in regard to piano repertoire.

44Rink, review of Musical Structure and Performance, by Wallace Berry. See Tim Howell, "Analysis and Performance: The Search for a Middleground," in Companion to Contemporary Musical Thought, Vol.2, ed. John Paynter, Tim Howell, Richard Orton, and Peter Seymour (London: Routledge, 1992), 679-714.

45Tim Howell discusses this point. See Howell, "Analysis and Performance," 698.

46Janet Schmalfeldt examines the roles of both the analyst and the performer in an imaginative format that allows each to act both as the presenter of and respondent to an interpretation of two short works. See Janet Schmalfeldt, "On the Relation of Analysis to Performance."