Frank Zappa might be described as a cultural guerilla. He sees that the popular arts are propagandistic in the broad sense—even when they masquerade as rebellion they lull us into fantasy and homogenize our responses. So he infiltrates the machine and attempts to make the popular forms defeat their traditional ends—his music doesn't lull, it tries to make you think.1

Consisting of both new and older pieces arranged and performed during election year 1988, Frank Zappa's stage composition and recording Broadway the Hard Way [hereafter referred to as BTHW] sum up his view of the social, political, and artistic "State of the Union," as presented in seventeen individual numbers performed by a twelve-piece ensemble. Zappa draws on a spectrum of musical idioms, employing complex techniques of allusion, quotation, and parody to invoke sonic associations, and then manipulates those associations toward complex programmatic ends.2

Heard in its entirety, Broadway the Hard Way is a unified, savagely satirical depiction of Zappa's vision of contemporary America; its rogues' gallery of public figures, its social ills and artistic malaise, and of his—the artist's—role in that society. This article identifies musical materials, explores compositional techniques, and clarifies artistic intent and expressive impact.3

From his first commercial releases Freak Out! (1966) and Absolutely Free (1967), Frank Zappa mined parallel veins of compositional complexity, social commentary, and scatological parody. With his various performing and recording ensembles he had employed techniques of musique concrète, American vernacular styles from rock to blues to country-western to doo-wop to Dixieland jazz, comedy, sound-effects, and complex polyphonic and polyrhythmic textures. The military-industrial complex, the Los Angeles music industry, the Washington political elite, and the whims of popular culture, from "Flower-Power" through recreational drugs, disco, and the "New Age," had been targeted by his biting wit.4

By the 1980s, he and his wife Gail ran their own record label (Barking Pumpkin), video company (Honker Home Video), publishing company (Barfko-Swill), recording studio (the Utility Muffin Research Kitchen) and umbrella corporation (Intercontinental Absurdities). Zappa had composed hundreds of works for all media (rock band, jazz big-band, chamber ensembles, electronics, digital synthesizer, and orchestra) and his band had become a demanding finishing school for dozens of superb instrumentalists.

At the time of the original preparations for BTHW (1986-87), Zappa was completing a period of public political involvement: specifically, in the battle fought in the U.S. House of Representatives between conservative elements (the Parents' Music Resource Committee5) and representatives of the recording industry. It was his view that the P.M.R.C.'s campaign for mandatory labelling of record albums with "adult" content was akin to censorship, and that the record industry's reaction as a whole was inadequate and excessively pacific. The tune "Porn Wars," on Frank Zappa Meets the Mothers of Prevention (1985), combined recorded performances and digitized snippets of his testimony and House Members' responses in musique concrète style to make a defiant political statement. More recently, Zappa had begun to speak out about the political connections and economic conduct of evangelical television networks, and in the face of the coming 1988 Presidential elections had initiated a campaign to encourage voter registration.

In the 1980s, Zappa despised the degree to which pre-programmable technology (samplers and sequencers) was de-emphasizing the skillful, improvisatory, human-oriented elements of live rock performance. He expressed a desire to uphold the high standard of performance virtuosity and audience interaction which had been integral to his work in the rock world, and which he saw dying out. (Certainly no other rock composer or ensemble had the breadth of vision and skills to improvise onstage with both Nicholas Slonimsky and National Public Radio's Daniel Schorr.6) Zappa was also in demand as a composer, having received commissions from numerous ensembles, including the Ensemble Intercontemporaine and the Berkeley Philharmonic.

Throughout his career, Frank Zappa wrote music which presumed that listeners would form associations to the material presented. Rather than resist this tendency, Zappa exploited and foregrounded its presence in order to expand his expressive palette. In this approach, allusive success is dependent upon accurate replication of style traits: without a clear and recognizable representation of an idiom's technical characteristics, the associations intended by the composer are likely to be missed by the listener, and result in bad imitation, not accurate parody.7 Such accuracy is particularly essential in programmatic works intended for the stage, where listener-comprehension must be effected on first hearing. Hence, allusion-oriented composers from Ives to Mahler and Mozart to Zappa have depended on the expert replication and manipulation of definitive style characteristics.8

General Procedures

Zappa codified his idiosyncratic compositional and interpretive procedures, developing a personalized terminology which he used both for description to outsiders and as "verbal shorthand" with his players. The techniques and terminology emphasize interpretive connotations: in "Zappa-speak," the addition to a composition of allusive style traits (or "Eyebrows") is distinguished from a performer's intended interpretive "Attitude" toward the composition, and the musical texture often exploits quotation of "Archetypal American Musical Icons."9

I've developed a "formula" for what these timbres mean (to me, at least), so that when I create an arrangement . . . I can put sounds together that tell more than the story in the lyrics, especially to American listeners, [who are] raised on these subliminal clichés, shaping their audio reality from the cradle to the elevator . . . During the pre[-]tour rehearsals, the band members pencil these "extras" in next to the "real notes" so, when they finally have the show learned, they know not only the song-as-originally-written but also, superimposed on it, a flexible grid which will support a constantly mutating collage of low-rent Americana.10

Such evocation of associations in a musical context is not limited to Zappa, or to modern popular idioms, but is a significant component of programmatic music's methodology. Of Mozart's invocation of contemporaneous populist styles, Leonard Ratner says:

This rapid succession of military, peasant, brilliant, brusque, and singing manners . . . must have suggested to Mozart's listeners that he was imitating an episode from commedia dell'arte, with its slapstick effects, its darting here and there, and its play of unexpected events.11

Zappa's compositional techniques derived from his years of experience as a touring bandleader, and the experimentation and refinement of procedures that this experience afforded him. His compositional and interpretive methodology (like that of another American "compositional individualist," Duke Ellington)12 was hammered out on the bandstand; he used it because he knew that it worked. Zappa was able to write for the strengths, outside experience, and peculiarities of specific individuals, upon whom he could depend for valuable interpretive, stylistic and improvisational input.13 (Such interaction was made particularly feasible because he required that the 100 or more pieces in a given tour's repertoire list be memorized.) As a result, composition did not cease when Zappa handed over written or verbal instructions to the ensemble; rather it continued, with improvisatory, collaborative additions made throughout the rehearsal, performance, and post-performance (editing) process.

Zappa also developed an onstage vocabulary to facilitate conducted improvisation:

There are cues used on stage . . . During any song, no matter what style it was learned in, on a whim I can turn around and do something like that [give a specific visual cue], and the band will restyle the tune.14 Each guy in the band understands what the norms and "expected mannerisms" are for these different musical styles, and will instantly "translate" a song into that musical "dialect.". . . Since rehearsal is a daily two-hour occurrence while we're on the road, the arrangements can often change overnight, based on the daily news or some morsel of tour-bus folklore.15

In BTHW, such a "morsel of tour-bus folklore" is manifested in repeated, improvised interpolations of the phrase "confinement loaf." As Zappa explained in the liner notes,16 he had heard a news item which described the positive effects on violent prisoners' behavior when they were fed a diet consisting of a soybean-based processed food called "confinement loaf." For a few weeks, "confinement loaf" became for Zappa a symbol of government's proto-fascist behavior-modification.

Percussionist Ruth Underwood confirmed the centrality of conducted improvisation:

"Let me tell you, Frank was leading the band from every possible aspect and angle and vantage point. He had a series of hand signals and the body language was very important too. We all had our eyes on Frank all the time. You had to, because you never knew what was going to happen. In the middle of doing something that was very much expected and rehearsed, he could just turn around and do something, he could gesture a certain way, or make a face . . . and the whole concert would take a completely different turn."17

In addition to moment-by-moment improvisational additions, new pieces were composed and premiered while the tour was in progress: "Promiscuous" (discussed below) was written in Chicago, and performed the same evening by vocalist Ike Willis, who read the lyrics from a sheet of paper.

Allusive Techniques

The music on BTHW is explicitly and intentionally situated in a referential context. It is targeted at a certain group of listeners with some range of musical experiences held in common, and it presumes that such listeners will hear allusions and make sonic connections. This music consciously invokes associations and then manipulates those associations to expressive ends. Zappa composed for a specific time and place, for specific people, from a specific perspective.18

Archetypal American Musical Icons

Zappa referred to certain stylistic, idiomatic, and timbral elements, and his manipulation of these elements for their allusive impact as "Archetypal American Musical Icons":

I attempt to devise "language" that will describe my musical intentions, in shorthand form . . . There's an assortment of "stock modules" used in our stage arrangements . . . These "stock modules" include the "Twilight Zone" Texture (which may not be the actual Twilight Zone notes, but the same "texture"), the Mister Rogers texture, the "Jaws" texture . . . and things that sound either exactly like or very similar to "Louie Louie." These are Archetypal American Musical Icons, and their presence in an arrangement puts a spin on any lyric in their vicinity. When present, these modules "suggest" that you interpret those lyrics within parentheses.19

Use of "Archetypal American Musical Icons," then, connotes deliberate compositional incorporation of musical quotation and allusion in order to influence reception. Such allusive material can consist of or combine motivic, rhythmic, textural, timbral, textual or harmonic elements.

Archetypal American Musical Icons are employed throughout BTHW, and include mock opera ("On the Planet of the Baritone Women"), blues ("Dickie's Such An Asshole" and "What Kind of Girl?") and blues-funk ("Bacon Fat"), heavy-metal rock ("When the Lie's So Big"), pop-rock ballads ("Any Kind of Pain"), Dixieland jazz ("When the Lie's So Big"), TV and film melodrama ("The Untouchables" and "Hot Plate Heaven"), pop-funk ("Why Don't You Like Me?"), strip shows ("What Kind of Girl"), country music ("Elvis Has Just Left the Building"), and Ravel's "Bolero" ("When The Lie's So Big"). Idiomatic allusions are utilized consistently from number to number and throughout the piece: for example, the gospel hymn "Rock of Ages," connoting ostentatious Protestant fundamentalism, is quoted at the ends of the first and final numbers ("Elvis has just left the building" and "Jesus thinks you're a jerk"—see Text Transcription #3, lines 26-27).20

A specific Archetypal American Musical Icon, "The Battle Hymn of the Republic" is quoted five times in four pieces, each time with consistent allusive intent:

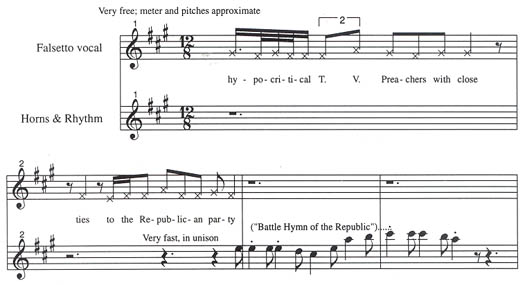

1) In "Dickie's Such An Asshole," to refer to former Republican U.S. President Richard Nixon;

Example #1. From "Dickie's such an asshole"

2) in "When the Lie's So Big," referring to Reagan-era Republican political leaders;

Example #2. From "When the Lie's So Big "

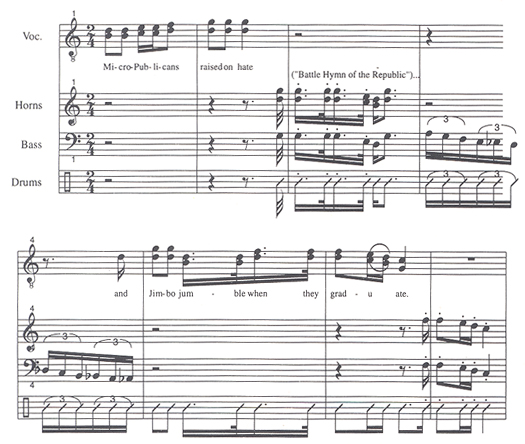

3) in "What Kind of Girl?," referring to television evangelist Pat Robertson's political affiliations; and

Example #3. From "What Kind of Girl?"

4) twice in "Jesus Thinks You're a Jerk," referring first to young members of the Republican party,

Example #4. From "Jesus Thinks You're a Jerk"

and then to lynch-mob mentality.

Example #5. From "Jesus Thinks You're a Jerk"

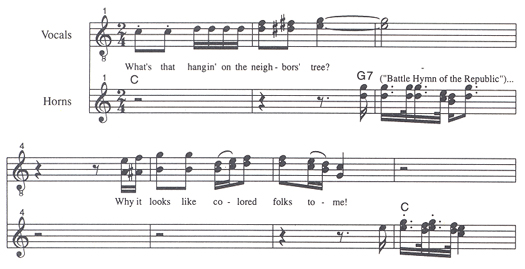

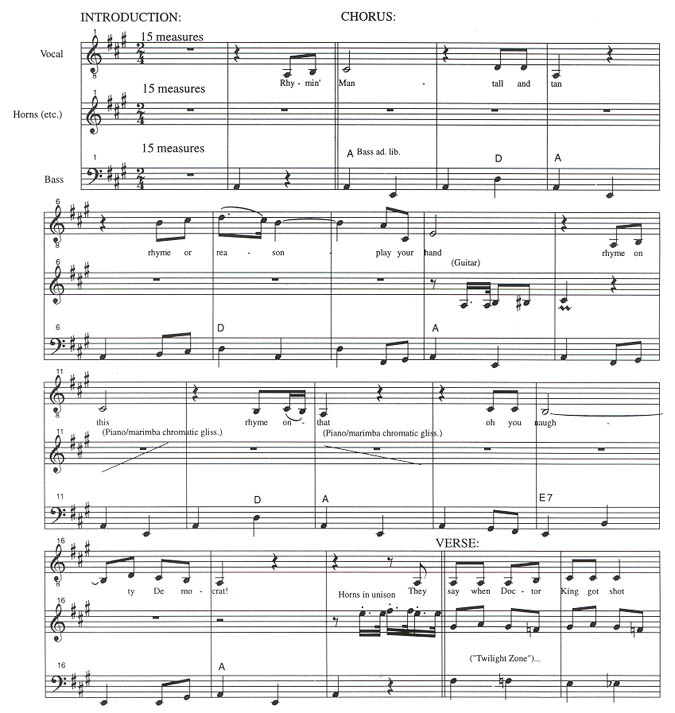

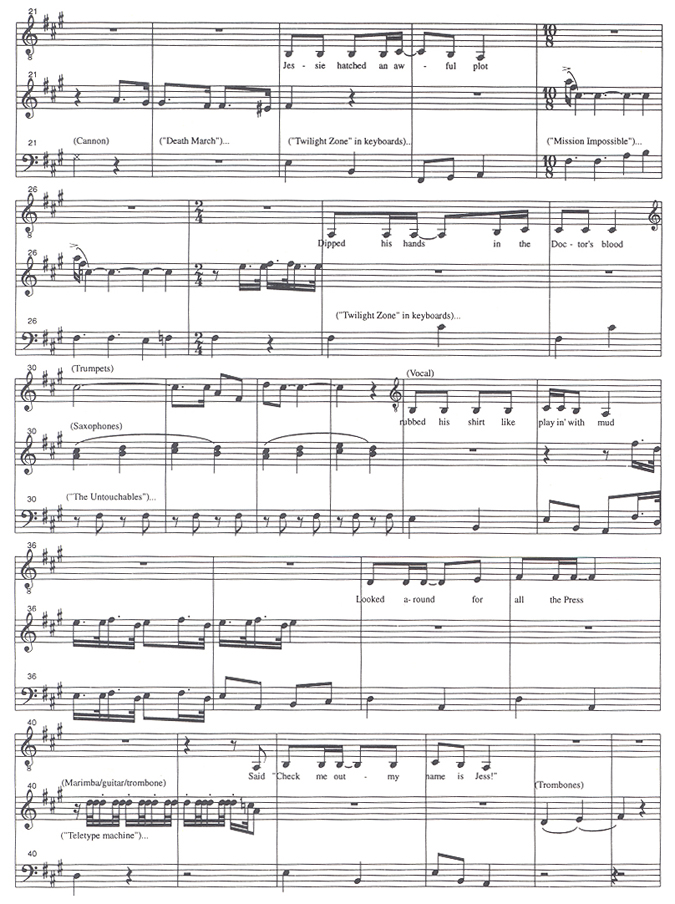

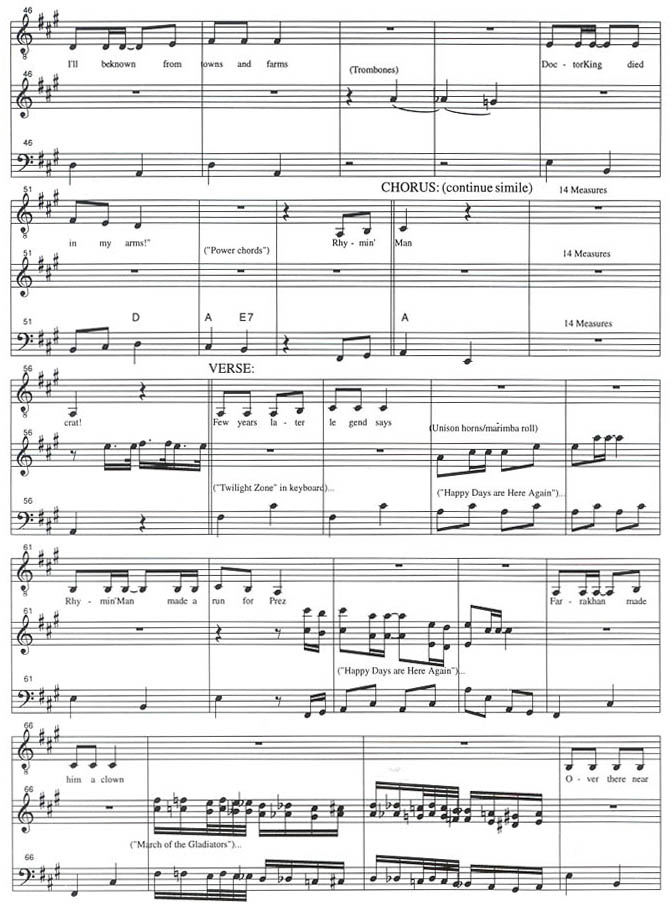

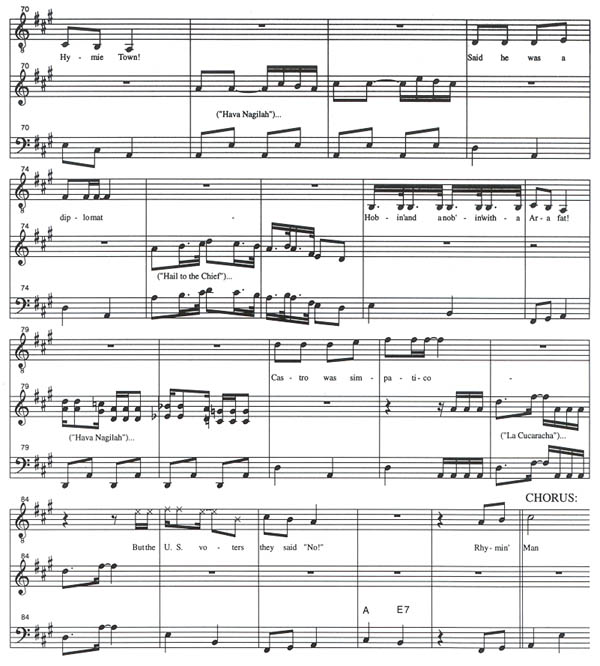

"Rhymin' Man," a savage critique of Jesse Jackson's political persona and style of discourse,21 is entirely constructed in order to facilitate the sophisticated semiotic manipulation of Archetypal American Musical Icons. The strophic structure, arpeggiated guitar licks, root/fifth-oriented bass part, and high tenor vocal harmonies are all defining characteristics of the cowboy-song genre.22 The idiom's antecedent-consequent phrase structure facilitates insertion of rapid-fire melodic allusions, including melodramatic television themes for "The Twilight Zone" (line 6: "Oh you naughty Democrat!"), "The Untouchables" (line 9: "Dipped his hands in the Doctor's blood"), and "Mission Impossible" (line 8: "Jesse hatched an awful plot"); stereotypical bits of ethnicity including "Hava Nagilah" (line 18, quoting Jackson's "Over there near Hymie-Town") and "La Cucaracha" (line 21: "Castro was simpatico"); evocations of the circus ("March of the Gladiators" at line 17: "Farrakhan made him a clown"), the Presidency ("Hail to the Chief" at line 19: "Said he was a diplomat") and the Democratic Party ("Happy Days are Here Again" at lines 15-16: "A few years later, legend says/Rhymin' Man made a run for Prez"); and the editorial implications of sound effects ("Teletype" motive at line 11: "Looked around for all the press"). All invoke associations, parody conventions, and comment on textual events. [See Music Example #6]

Example #6. Excerpt, "Rhymin' Man" by Frank Zappa (transcribed CJS)

Eyebrows

Zappa labelled and described a different type of allusive technique as follows:

Songs written with one idea in mind have been known to mutate into something completely different if I hear an "optional vocal inflection" during rehearsal . . . The "technical expression" we use in the band to describe this process is: "PUTTING THE EYEBROWS ON IT". . . You can put the eyebrows on just about anything . . . Since most Americans use a personal version of eyebrowsage in their conversational speech, why not include the technique as a "nuance" in a composition?23

"Eyebrows," then, are the sonic equivalent of the facial expressions used in the context of conversation: gestural or stylistic behaviors or inflections which color the semiotic reception of sound material.

A specific "Eyebrow" appears several times in "Jesus Thinks You're a Jerk." Each time, vocalist/guitarist Ike Willis contributes a rendition of the comedian Billy Crystal's imitation of Las Vegas entertainer Sammy Davis, Jr. Following the lines "'Specially if they [evangelists] cover it up/Saying Jesus told it to me," (lines 6-7) Zappa has "Sammy Davis" add "I mean, babe, we're tight." This is not a musical quotation, but a reference to an inflected mode of discourse, conveyed in a nutshell by imitation of a specific public figure's patterns of speech. At Zappa's direction, Ike Willis evokes the intimacy with the Deity claimed by some television evangelists, equates it with the extremely public intimacy displayed in Las Vegas stage shows, and plays the textual "tragedy" for laughs. [See Text Transcription #3, lines 7-8]

The approach of "Rhymin' Man" described earlier—quoting Archetypal American Musical Icons so densely that they saturate the texture—contrasts with the genre-oriented "Eyebrowsage" of "Promiscuous." Here, semiotic impact depends not on melodic quotation but upon accurate performance within the confines of a specific idiom: the Bronx-style rap of Run-DMC. The parodistic and absurdist juxtapositions work at both general and specific levels: the satirical target is Surgeon General C. Everett Koop, whose public persona (commanding, Caucasian, military, and patrician) is ironically framed by rap music, an idiom more usually associated with urban African-American street culture. While unexpected, the juxtaposition is an effective compositional choice: on the general level, rap's textual focus makes it a good vehicle for wordplay, and on the specific, the band's virtuoso replication of the idiom's style characteristics drives the humor home.24

Wye Jamison Allanbrook describes analogous genre humor in Don Giovanni, noting both the conceptual and the technical requirements of such parody:

[Donna Elvira] lurches in to the accompaniment of a stiff and archaic ritornello . . . Mozart takes the greatest care to make the aria seem odd and old-fashioned . . . The effect is eccentric, to say the least—a "conceptual" aria, cleverly working the archaic technique of Fortspinnung into a periodic setting . . . [which] contributes to the aria's deliberate air of obsolescence.25

Just as in Zappa's "Rhymin' Man" and "Promiscuous," Mozart's inflected use of an "Archetypal [Viennese] Musical Icon" for parodistic purposes is successful precisely because the musical texture accurately replicates and manipulates the archaic style.

Attitude

Zappa described the overall expressive intent of a composition as "Attitude":

The ultimate tweeze inflicted on the composition is determining The Attitude with which the piece is to be performed. The player is expected to comprehend The Attitude, and to perform the material with The Attitude AND The Eyebrows, consistently.26

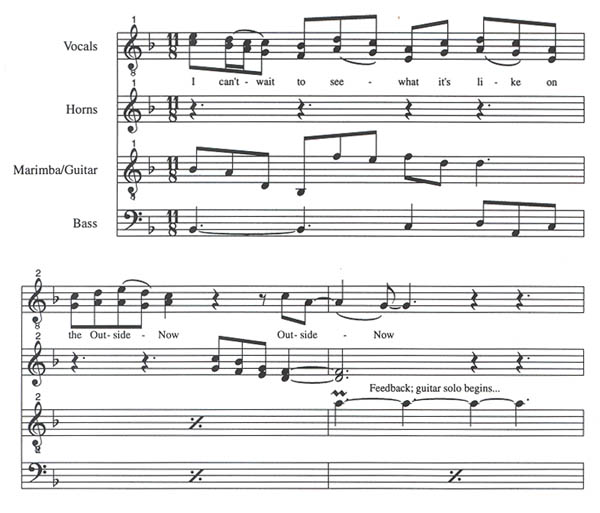

The song "Outside Now" occupies an interesting "Attitudinal" position in BTHW. The piece originally appeared in Zappa's album opera Joe's Garage, a fable of musical repression, where it was sung by the title character, an erstwhile musician who is eventually brainwashed by political officials in order to destroy his commitment to music as an expressive form.

Compositionally, it is the only number which is simultaneously devoid of the quoted "Archetypal American Musical Icons" central to "Rhymin' Man," and which avoids the genre-imitation and parody of "Promiscuous." Textually, it is the only number in which a character—a creative musician marginalized by a brutal social situation—speaks in extended first-person expression, untempered by sarcasm, comedy, or ironic distance. In the bitter, defiant lyrics, in the characterization, and most crucially in the guitar solo, the "Attitudinal" voice is that of the composer himself.

Based on a repetitive 11/8 meter [Music Example #7], "Outside Now" is compositionally structured to fit Zappa's own improvisational preferences: slow tempo, open texture, repetitive modal chord changes, and an ostinato bass line which frees the drummer to interact rhythmically with the soloist.

Example #7. From "Outside Now"

Moreover, in the 1980s context of drum machines, three-minute pop songs, and MTV lip-synching, "Outside Now's" unusual style traits are themselves a statement of iconoclastic artistic politics. In the guitar solo which is "Outside Now's" expressive core, Zappa speaks with an uncluttered, brutal eloquence, in a defiant statement of longevity, endurance, and commitment.27

In sum: "Archetypal American Musical Icons" are short quotations or allusions which invoke sonic associations, "Eyebrows" are vocal and instrumental inflections superimposed on pre-composed material, and "Attitude," the product of compositional instruction, combines the affective stance, connotations, and results intended by a given piece. In Zappa's case, such techniques derive from jazz, rock, and other oral/aural performance traditions.28 But the more general idea that a performance's expressive effectiveness depends upon the players' understanding of compositional intent, as well as instructions, reaches back to the Classical period.29 Moreover, when the procedures are part of an integrated compositional vocabulary, their enactment demands an ensemble conversant with that vocabulary.

From his earliest days as a bandleader (and especially the Dadaist performances at New York's Garrick Theater in 1967), Zappa recruited players and conducted onstage performances so as to elicit and encourage performer-performer and performer-audience interaction, to such an extent that the audience became "co-creators" of a given evening's performance. Over the years, fans who repeatedly attended concerts learned to expect extra-musical onstage business, including comedic skits, solicitations of underwear, and the ritual of the "secret word:" at a given show, Zappa would tell the audience that a given word or phrase was the "secret word for tonight," which over the course of the performance would be unexpectedly and comically inserted in place of standard texts.30

Isolation and close examination of a few of Zappa's allusive techniques illuminate connections between his stage works and others from the Euro-American tradition. I do not want to say that BTHW is, for example, "like" Don Giovanni, but to show that the two works share some goals and procedures. Composers drawing extensively on allusive approaches consistently utilize the technical characteristics of populist music styles (including motive, form, texture, orchestrational detail, text style, etc.), specifically because they invoke associations. In this way, allusive techniques situate the composition in a sonic world of musical genre, experience and memory. What results is a participatory, interactive process between composer, performers, and audience, in which reference, quotation, allusion, and parody become the signposts, and the semiotic tools, of a shared perceptual experience.

In their respective historical and personal contexts, Zappa and Mozart wrote music which successfully integrated musical and dramatic structure, melodic, harmonic, stylistic and textual allusion, and popular and vernacular culture.31 They constructed effective stage works which functioned on the level of archetypal human commentary but also of localized, allusive social-political satire. With Broadway the Hard Way, working in the carnival-funhouse environment of American popular culture careening into the 21st century, Frank Zappa realized a consistent personal, political, and expressive vision.

Appendix: Topoi from "Broadway the Hard Way"

Note: my goal in offering selective transcriptions of pieces cited in the article is threefold: 1) to facilitate understanding of the interaction of text, accompanying music, and musical quotation; 2) to convey something of the density of sonic events; and 3) to provide a key to references which may be unfamiliar. I have numbered lines to facilitate reference to the article's text.

Text Transcription #1: "Rhymin' Man" Strophic Cowboy song employing Archetypal American Musical Icons. Text as reproduced in CD notes; [brackets] indicate audio variants.

[8 measure introduction]

[Chorus]

Rhymin' Man

1. Tall and tan

2. Rhyme or reason

3. Play your hand -

4. Rhyme on this -

5. Rhyme on that -

6. Oh, you naughty Democrat!

Texture: Combines melodramatic and "nightmarish" associations of the musical theme to the "Twilight Zone" (an early-1960s science-fiction TV program) and the redundancy and simplicity of "Frère Jacques" (a repetitive, sing-song nursery rhyme familiar to most Americans from childhood)

7. They say when Doctor King got shot, "Funeral March" evokes sorrowful death

8. Jesse hatched an evil [awful] plot Theme to "Mission Impossible," a mid-1960s action/spy television program whose plots usually referenced conspiracies.

9. Dipped his hands in the Doctor's blood, Theme to the "Untouchables," an early-1960s television crime drama.

10. 'N rubbed his shirt like playin' with mud

11. Looked around for all the press, "Teletype" motive: a syncopated single-note figure often used on film soundtracks to evoke newspapers' tickertape machines.

12. 'N said: "Check me out, my name is Jess! [Trombone fill on wide, comic glissando]

13. I'll be known from towns 'n farms - [trombone fill]

14. Doctor King died in my arms!" I - V7 Power chords"32

[Chorus]

15. A few years later, legend says, Antecedent phrase to the Democratic theme song "Happy Days are here again;" alludes to Jackson's bid for the Democratic Presidential nomination

16. Rhymin' Man made a run for Prez Penultimate phrase of "Happy Days"

17. Farrakhan made him a clown, Circus associations of "March of the Gladiators"

18. Over there near Hymie-Town Antecedent phrase of "Hava Nagilah," a stereotyped Ashkenazic Jewish dance song

19. Said he was a diplomat March "Hail to the Chief;" alludes to U.S. Presidency

20. Hobbin' an-a-nobbin' with Arafat Consequent phrase:" Hava Nagilah"

21. Castro was simpatico, "La Cucaracha," battle song of Mexican revolution

22. but the U.S. voters, they said

23. No! I - V7 power chords

[Chorus]

24. Okay, here we go again! Democratic associations of "Happy Days;" also note here the literal "dissonance" of the setting (and the attempt)

25. Rhymin' Man says he's your friend Dissonant "Happy Days" (see reference above)

26. Any fool can make a rhyme - "Frère Jacques" (see allusions cited above)

27. Cowboys do it all the time "Frère Jacques" in dissonant harmony

we sure do/we sure do

28. People say "Now he's mature!" "My Sharona"33

29. Cowboys rhyme that with horse manure "My Sharona;" note also the textual rhyme "mature" & "manure"

[Sung to the melody of the Chorus]:

30. Horse manure!

31. That's for sure!

32. You been cheatin' -

33. We kept score!

34. Are you "this"?

35. Or are you "that"?

36. Oh, you naughty

37. Democrat "Hallelujah I'm a Bum"34

Text Transcription #2: "Promiscuous" Mid-1980s Bronx-style rap, employing "Eyebrows." Note evocation of rap's style characteristics: turntable "scratching," processed drum sounds, heavy metal lead guitar, and specific vocal styles and inflections. Also note the dearth of specific melodic quotations; the piece is based on style replication, compared to No.1 above, which is based on melodic quotation.

1. The Surgeon General, Doctor Koop35

2. S'posed to give you all the poop

3. But when he's with P.M.R.C.36

4. The poop he's scoopin'

5. Amazes me6. C-Span37 showed him, all dressed up

7. In his phony Doctor God get-up38

8. He looked in the camera and fixed

9. His specs

10. 'N gave a little [fascinatin'] lecture

11. 'Bout anal sex12. He says it is not good for us

13. We just can't be promiscuous39

14. He's [just] a doctor he should know

15. It's the work of the Devil, so

16. Girls, don't blow!4017. Don't blow Jimmy, don't blow Bobby

18. Get yourself another hobby

19. (If Jesus practiced medicine

20. I'm sure he'd do it

21. Just like him)4122. Is Doctor Koop a man to trust?

23. It seems at least that Reagan must

24. (But Ron's a trusting sort of guy

25. He trusts Ed Meese42

26. I wonder why?)27. The A.M.A. has just got caught

28. "For doin' stuff it [they] shouldn't ought43

29. All they do is lie and lie

30. Where's Doctor Koop?

31. He's standin' by32. Surgeon General? What's the deal?

33. Is your epidemic real?

34. Are you leaving something out?

35. Something we can't talk about?

36. A little green monkey over there44

37. Kills a million people?

38. That's not fair!

39. Did it really go that way?

40. Did you ask the C.I.A.?

41. Would they take you serious?

42. Or have THEY been promiscuous? [3x]

Text Transcription #3: "Jesus thinks you're a jerk" (excerpt) Multi-stylistic, employing quotation and allusion at all levels in a particularly complex shifting texture.

"Lounge Lizard" Texture45

1. "What if Pat46 gets in the White House Sung: "No fuckin' way, Ike, you know what I mean?"

2. [missing: And suddenly ]

3. The rights of "certain people" disappear "Mysteriously?"

4. Now, wouldn't that sort of qualify

5. As an American Tragedy? "Lounge Lizard"-style vocal (see quotation, p.6)

6. (Especially if he [they] covers [cover] it up, sayin'

7. "Jesus told it to me!")

Spoken: Sammy Davis "I mean babe, we're tight."

Momentary change to "Twilight Zone" Texture.47 Ongoing Sammy Davis "Eyebrow" within texture. Change texture back to "Lounge Lizard:"

[Following is sung by Zappa solo]48

8. I hope we never see that day,

9. In The Land of The Free

10. Or someday will we? "Twilight Zone" quotation

Spoken: "92?"49

11. Will we? "Twilight Zone" quotation

Spoken: "96?"50

12. And if you don't know by now,

13. The truth of what I'm tellin' you,

14. Then, surely I have failed somehow [repeat 3x]

15. And Jesus will think I'm a jerk, just like you "March of the Gladiators" evoking circus/carnival hucksterism.

16. If you let those TV Preachers

17. Make a monkey out of you! "Lounge Lizard" vocal fill (see above).

18. I said: "Jesus will think you're a jerk,"

19. And it will be true! Stereotypically clumsy, pop-style modulation.

Change to combined texture: "Rock of Ages"51 overlapped by "Dixie"52.

20. There's an old rugged cross

21. In the land of cotton/[the stainless maiden] "Dixie" consequent phrase

22. It's still burnin' on somebody's lawn,

"But this person looks like Tom Breeden!"53

[missing] And it still smells rotten

23. Jim and Tammy! "Louie Louie"54

24. Oh, baby!

25. You gotta go!

26. You really got to go! modulation, with "Dixie" and "Rock of Ages" played simultaneously.

[Coda: sung to the tune of "Rock of Ages:"]55

27. Jim and Tam-my got-ta go!

[Zappa] Ladies and gentlemen, this is intermission. Get your butt out there and register to vote, would ya please? See you in a half an hour.

CITATIONS

Aiken, Jim and the Editors of Guitar Player magazine. A Definitive Tribute to Frank Zappa (1993 special issue).

Allanbrook, W. Jamison. Rhythmic Gesture in Mozart: "Le Nozze Di Figaro" and "Don Giovanni." Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1983.

Editors. Musician 184 (February 1994).

Fricke, David. "Frank Talk (Interview)." Rolling Stone (November 1986).

Fricke, David. "Frank Zappa (Beacon Theater Concert)." Rolling Stone (24 March 1988).

Kart, Larry. "Frank Zappa: The Mother of Us All." Downbeat 38 (November 1969): 14-15.

Lomax, John and Alan Lomax. American Ballads and Folk Songs. New York: MacMillan, 1934.

Menn, Don and the Editors of Guitar and Keyboard magazine. Zappa! (1992 Special Issue).

Ratner, Leonard G. Classic Music: Expression, Form and Style. New York: Schirmer, 1980.

Slonimsky, Nicolas. "Meeting Zappa." Excerpt from Perfect Pitch. In Harper's Magazine, April 1988.

Watson, Ben. The Negative Dialectics of Poodle Play. London: Quartet, 1994.

Zappa, Frank. "Frank Zappa on Edgar Varèse." Interview by John Diliberto and Kimberly Haas. Downbeat 48 (November 1981): 21-23.

Zappa, Frank, with Peter Ochiogrosso. The Real Frank Zappa Book. New York: Poseidon, 1989.

Zappa, Frank. "BBC Television Tribute," The Late Show, British Broadcasting Corporation, broadcast 11 March 1993.

Zappa, Frank. Interview with Bob Marshall. Tape recording, 22 October 1988. Los Angeles, CA. Electronic file retrievable by World Wide Web Browser as filename Part01.html from "St. Alphonzo's [sic] Pancake Homepage" (http://www.fwi.uva.nl/~heederik/zappa/interviews/Bob_Marshall/).

[Personal note: Frank Zappa died in 1993, at the age of 52, after a lengthy, painful, and courageous battle with prostate cancer. Ruth Underwood, mallets player in his touring band for a number of years, articulated her sense of loss and gratitude:

Frank composed music for my hands. He composed music for my temperament, my neuroses, my humor—Frank custom-tailored those parts to me . . . I'm not a composer but I felt like one when I played Frank's music.56

A lot of people felt the loss of Frank's musical mind, humor, and fearless honesty: friends, fans, players, politicians (whom he called "the entertainment branch of industry"),—even musicologists. I am very sorry he's gone.]

1Larry Kart, "Frank Zappa: The Mother of Us All," Downbeat 38, (November 1969): 14-15.

2For the purposes of this analysis I will treat the compact disc recording of concert performances as the "work." Zappa's compositional process ranged from completely-notated complex scores to compositions constructed entirely through improvisation and/or verbal instruction. Moreover, the process extended past the original notation or instructions to include additions made in rehearsal and subsequent performances, as well as post-recording editing and sequencing decisions. Therefore it seems reasonable to treat all of this tinkering as part of the "compositional process." In the case of BTHW, no scores are publically available, and most of the material was learned aurally and played from memory, so the CD is the best and most appropriate document.

3Most analysis of rock/pop-based commercial music has tended to derive from culture studies [Greil Marcus, Lester Bangs] or sociology [Simon Frith], historical studies [Peter Guralnick], or political sciences [Ben Watson, cited ahead]. These authors and others have tended to analyze pop music as cultural expression, and to "focus outward" from the music in order to analyze the cultural context in which it is created. This has often resulted in a de-emphasis of the music itself. In contrast, in this article I am interested in a synthesis of musical-analytical techniques, an approach I feel is particularly appropriate to Zappa's work.

4There is not much in the scholarly literature on the music of Frank Zappa; though in the wake of his death new literature is appearing, most commentary on his activities has been in the popular press. Ben Watson's recent Frank Zappa: The Negative Dialectics of Poodle Play (London: Quartet, 1994) makes some attempt to redress this imbalance. However, Watson's textual orientation, and desire to analyze Zappa through the prisms of serialism, Adorno, Marxist theory, and many other topics of which the composer proudly professed ignorance, calls some of his conclusions into question. The best and most apposite text remains Zappa's own The Real Frank Zappa Book (New York: Poseidon, 1989), in which prose style, topical orientation, and general "Attitude" accurately reflect Zappa's unique perspective and style of discourse.

5A group created in 1985 by wives of prominent Congressmen ("Mrs. James Baker," "Mrs. Fritz Hollings," "Mrs. Albert Gore" were among the signatures which appeared on documents), which attempted to force the U.S. record industry to enact a self-imposed process by which record albums would be "stickered" as appropriate or not appropriate for certain age groups. The group held no official status on Capitol Hill, but did receive tax-exemption. At the P.M.R.C.'s insistence, amendments on this topic had been added to various pieces of legislation sponsored by the Science, Commerce, and Transportation Committee, on which members' Congressional spouses served. Zappa had testified before this Committee in October of 1985.

6On February 10, 1988, in Washington, D.C., the band improvised a version of "It Ain't Necessarily So," from Gershwin's Porgy and Bess, with Daniel Schorr singing the lead vocal. The performance's location, at the locus of the U.S. Federal Government, and Schorr's position as Senior Political Commentator for National Public Radio, lent additional layers of allusive meaning. The band played "Danny Boy" as Schorr came to the stage, and followed "It Ain't Necessarily So" with a brief quotation of "Summertime," also from Porgy, followed in turn by the "Royal March" from Verdi's Aida. Such multireferentiality, stylistic collisions and "chance events" were standard onstage procedures.

7This was a possibility which Zappa explicitly recognized: "In order to make fun of something everybody has to know the ground rules for the joke to work. So [for example] it would be ridiculous to make fun of punk orchestration, unless everybody else had some idea of what punk sounded like so that you can make a parody of it." Frank Zappa. Interview with Bob Marshall, lines 40-46 (Hereafter referred to as Marshall). Tape recording, 22 October 1988, Los Angeles, CA. Electronic file retrievable by World Wide Web Browser as filename Part01.html from "St. Alphonzo's [sic] Pancake Homepage" http://www.fwi.uva.nl/~heederik/zappa/interviews/Bob_Marshall/).

8In Ratner's description of Don Giovanni, if we substitute Zappa's "Broadway the Hard Way" for Mozart's "comic opera," the procedural parallels become particularly clear:

"As an autonomous genre [comic opera] could act as a lens through which the whole world was viewed, and a mask behind which bitter and subversive social comment could be delivered . . . The sense of immediacy in comic opera, the "here and now" ambiance, was achieved through a highly volatile musical idiom . . . [ranging] from sentimentality at one end to furious effervescence at the other . . . [with a] prevalence of dances, simple songs, mock-military, mock-serious, and rustic styles . . . [deployed] for extravagant or parodistic effect." Leonard Ratner, Classic Music: Expression, Form and Style (New York: Schirmer, 1980), 394.

9I focus for the sake of brevity on techniques specifically labelled by the composer. Many others are similarly and consistently identifiable, but are beyond the scope of this article.

10The Real Frank Zappa Book, 173. Here, as in all other quotations from this work, all emphases are original.

11Leonard G. Ratner, Classic Music: Expression, Form and Style (New York: Schirmer, 1980), 389.

12This performance-oriented and -derived methodology is also a significant factor in the careers of American jazz musicians like Charles Mingus and Miles Davis, New Music performers including Philip Glass, Steve Reich, and Meredith Monk, blues musicians like Muddy Waters, and folk musicians from Bill Monroe to Bob Wills.

13"For me it was always more interesting to encounter a musician who had a unique ability, find a way to showcase that, and build that unusual skill into the composition. So that for ever and ever afterward, that composition would be stamped with the personality of the person who was there when the composition was created." Frank Zappa, "BBC Television Tribute" The Late Show, British Broadcasting Corporation, broadcast 11 March 1993, (hereafter cited as BBC Television Tribute).

14A wonderful demonstration of this interaction appears in the BBC Television Tribute: Zappa is shown conducting a rehearsal with the Ensemble Moderne. At a certain moment, he drops his hand, and the orchestra shouts in unison: "AIIIEEEE!". Zappa nods with a gratified smile, saying "Now, you have to remember these things because they can happen any time."

15The Real Frank Zappa Book, 164-166.

16Frank Zappa, Liner Notes to Broadway the Hard Way LP version (1988).

17BBC Television Tribute.

18"What I have to do is make an assumption about the comprehension abilities of the people that would be the likely consumers for what I do. In other words, I have to conjure up in my brain an imaginary picture of who the guy is, how smart he is, how many references he might have that I can make through metaphorical references in a work . . . That's the data that went into building the [compositional] model." [Marshall]

Such focus on evocation and manipulation of individuals' sonic associations and recollections connects Zappa to other American composers, a connection more fully developed in my paper "Frank Zappa, Charles Ives, and the search for an American vernacular." [Unpublished]

19The Real Frank Zappa Book, 166.

20Zappa referred to such consistency of allusion, which ranges over the course of his entire career, as "Conceptual Continuity." A comprehensive analysis of this aspect of his work remains to be written, though The Negative Dialectics of Poodle Play [cited above] addresses author Ben Watson's own "Conceptual Continuity" regarding Zappa. But Watson's analysis is overwhelmingly oriented toward analysis of text, not music.

21"I did this song about the idea of communicating through nursery rhymes, as Jackson is prone to do. It rubs me the wrong way. I'm not saying that all of Jesse's ideas are bad; I agree with some of them. But I'm not confident that Jesse Jackson would be the person I would look to to implement any of them." Frank Zappa, interview in Playboy (May 2, 1993). Electronic file retrievable by World Wide Web Browser as filename Playboy.html from "St. Alphonzo's [sic] Pancake Homepage" (http://www.fwi.uva.nl/~heederik/zappa/interviews/Playboy/).

22"I Ride an Old Paint," "Cool Water," etc.

23The Real Frank Zappa Book, 162.

24The improvisational and stylistic virtuosity becomes all the more impressive when it is recognized that this version of "Promiscuous" is both the premiere, and the only extant performance: it was performed one night only, and it is that unique event which appears on BTHW.

25W. Jamison Allanbrook, Rhythmic Gesture in Mozart: "Le Nozze Di Figaro" and "Don Giovanni" (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1983), 235-237.

26The Real Frank Zappa Book, 163.

27"Outside Now" recalls elegiac improvisations by other American musicians: in particular, John Coltrane's lament "Alabama," taken from the cadences of a speech made by Martin Luther King after a Ku Klux Klan bombing [Barry Kernfeld, New Grove Dictionary of Jazz Vol. I (New York: Macmillan, 1988), 237]. In the wake of Zappa's premature death, the words of the refrain "I can't wait to see/What it's like/On the Outside Now," take on a poignant additional meaning.

28Influential American bandleader-composers working in improvisational genres—including Ellington, Mingus, Meredith Monk, Miles Davis, Laurie Anderson, Bill Monroe, Muddy Waters, Steve Reich, and Philip Glass—have emphasized the essentiality of personalized interpretive instructions, and have resisted performances not supervised by the composer.

29Discussing "Ideas of Expression" in Mozart's rhythmic conception, Ratner quotes Rousseau's Dictionnaire of 1768: "It amounts to little simply to read the notes exactly; it is necessary to enter into all the ideas of the composer, to feel and render the fire of his expression." Ratner, Ibid., 3.

30During the 1988 tour, the range of allusive "secret words," many drawn from media sound bites, included "confinement loaf," "sausage," "raffle," "sodomy," "tunafish," "jellyfish," "pizza," "Ed Meese," "Jimmy Swaggart," "Ring O' Fire," and "just the tip."

31Ratner says of Mozart's stage works: "[The work] gathers as many diverse elements as possible into a coordinated structure. In drama, Shakespeare is the epitome of this approach; for classic music, Mozart's Don Giovanni achieves this goal." Ratner, Ibid., 411.

32Distorted guitars on block chords moving in parallel harmony.

33"My Sharona," by the late 1970s band the Knack, was quoted by Zappa in a number of contexts. In an example of what he called "Conceptual Continuity," the tune is always used to evoke the redundancy, over-simplicity, and cynical monetary motives he attributed to most pop/rock styles.

34A song which comes from the U.S. Depression of the 1930s, and here perhaps evokes Democratic "tax and spend" economics which resulted in massive budget deficits:

"Hallelujah I'm a bum/Hallelujah bum again/Hallelujah give us a handout and/Revive us again." John Lomax and Alan Lomax (ed.) American Ballads and Folk Songs (New York: MacMillan, 1934), 26-28.

35C. Everett Koop, Surgeon General during Ronald Reagan's Presidency 1980-1988.

36Headed by Tipper Gore, the Parent's Music Resource Committee was an organization chaired by several wives of prominent U.S. Congressmen, who were themselves without any Congressional status. The organization insisted upon ratings for record albums, similar to the Motion Picture Association of America's ratings for films. Zappa's Jazz from Hell, an all-instrumental work, was the second album to be stickered as "obscene - not for sale to minors." He took this apparent paradox (the idea that instrumental music might carry an "obscene" message) as indicative of the organization's extra-musical, politically-manipulative goals.

37A 24-hour cable television news channel.

38Admiral Koop often wore a white U.S. Navy Uniform in official appearances as Surgeon General.

39Reference to Koop's oft-repeated dictum for AIDS prevention: "Abstinence is the only sure means of avoidance."

40To perform fellatio.

41Koop was also prominent in conservative religious circles.

42Reagan-era Attorney General indicted for lying to Congress.

43The American Medical Association sponsored a publicity campaign which attempted to discredit alternative medicine, a monopolization ploy which incensed Zappa: "The AMA is certainly nothing to brag about. They got caught with that little scam that they tried to pull against the chiropractors recently." [Frank Zappa, in Marshall.]

44Reference to an early claim that inception of AIDS in Central Africa was due to animal bites upon humans.

45Parodic imitation of mediocre nightclub "lounge" music.

46Pat Robertson, television evangelist and 1988 Presidential candidate.

47Associations of nightmarish unreality.

48The atypical but significant use of first-person case in Zappa's own singing voice suggests that he intends these lines to be taken as direct address.

49Presidential election year.

50Presidential election year.

51Associated with Fundamentalist or Evangelical Christianity.

52Evoking the "plantation culture" and social perspectives of the post-Civil War American South.

53American Congressman.

54Three-chord mid-60s garage-band anthem, a central item in Zappa's "Conceptual Continuity. See Footnotes 20 and 33.

55Note "Conceptual Continuity:" In addition to being the final melodic material and final quotation in the final number of BTHW, "Rock of Ages" was also the first quotation material heard, in "Elvis has just left the building."

56Percussionist Ruth Underwood, quoted in Musician 184 (February 1994): 20-35. With thanks to Jason Carucci for locating the quotation.