Discrimination against women employed in higher education is receiving increased attention as our nation strives to correct gender inequities deeply entrenched in society. It is disturbing to imagine that different realities exist for males and females on our country's campuses in what is purported to be a society of equal opportunity.1 Although research results have been inconclusive regarding the relationship between inequality in society and inequalities within the education system, it stands to reason that as generations of young men and women observe individual and institutional role models in higher education they may be imprinting the values of those institutions. Those values continue intentionally or accidently to erect barriers to female participation in what are traditionally male roles on college faculties.

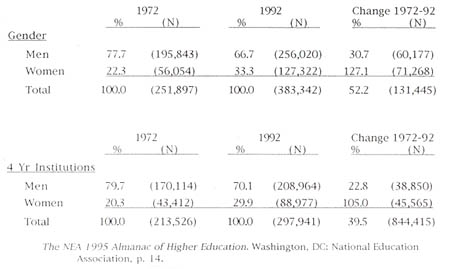

In 1972 the federal government enacted numerous laws and policies, most notably Title VII, designed to eliminate sexual discrimination in the workplace. Since that time the proportion of all full-time university faculty who are female has grown from 22% in 1972, to 33% in 1992—a 105% increase over the twenty year period2 (See Table 1).

Table 1. Distribution of U.S. higher education faculty by gender, institution type and change 1972-1992

Although this increase is encouraging, most of the gains have occurred primarily in lower ranks and in community colleges. Women are still under-represented in many disciplines. Women also continue to be employed in a relatively narrow number of academic departments, such as English, nursing, foreign languages, home economics, and education.3

Since at least two-thirds of our faculty members continue to be male, it appears that changes in legislation and policy over the past twenty-three years have not produced equal opportunity for women in higher education. As Sandler speculated:

Many people believe that campus discrimination against women has ended. They see the abolition of most overtly discriminatory policies, as well as an increasing number of women in graduate school and as faculty—albeit at the lower levels. They see women treated pleasantly by men, and perhaps they see one or two highly-placed women administrators. Thus, it is easy for many to assume that discriminatory treatment is no longer a significant problem for women in higher education.4

If the academic community has become de-sensitized to the issue of gender equity, it becomes increasingly important to persist in research efforts which will illustrate discrimination in employment, salary, and promotion in higher education, and ascertain the underlying social and cultural causes which continue to support such imbalances.

Financial equity problems have surfaced in studies in California, Pennsylvania, Virginia, Minnesota, Illinois, Florida, Massachusetts, and New Hampshire, where female university faculty members continue to receive approximately 15% less salary than their male counterparts with similar job assignments.5 Subsequent research also found that the primary determinants of faculty salary, regardless of institution size or discipline, were time spent on research, seniority, and being male.6

Gender and Music

Examinations investigating the influence of gender on various musical issues have provided limited and often conflicting information. Trollinger analyzed four scholarly music journals and determined that during the past twenty-five years, gender had been used as a dependent variable in a total of 104 research efforts using a variety of age levels, topics, and designs. She reported that females differed from males in the areas of vocal skills, motor skills, and instrument preference, musical ability, aural skills, tonal memory, anxiety, and positive attitudes toward music. A total of twenty-four studies on many of these same variables found no differences based on gender and nineteen studies achieved mixed results between the sexes on certain variables. She also concluded that recent research has been ineffective in assessing causes for these differences aside from broad theories of acculturation and maturation. Trollinger went on to say it appeared that sex-role stereotypes common in society have transferred to musical issues through the historical view that singing and music instruction are primarily feminine pursuits. She also suggested that biological influences need more study as a cause for gender differences in music.7

Public school music teachers are influential role models for young musicians. A recent survey of arts programs in public secondary schools found that 57% of public school choral teachers were female and 43% were male. It was also noted that while public secondary school choral music teachers were primarily female, instrumental music teachers were overwhelmingly male (80%).8

One of the arguments defending the male majority in university faculties is the assertion that few women are qualified to hold a tenure-track position. This assertion is not supported by Renton, who compared women in music with women in the general working population. She found that the number of females who earned advanced degrees in music was over 23% and concluded that a viable number of qualified candidates existed for positions on university faculties.9 Neuls-Bates also reported that while women had earned almost 50% of all master's degrees and nearly 15% of all doctoral degrees in music, they nonetheless continued to be excluded at the upper ranks on university faculties. She also reported that more women had achieved advanced degrees in music than in many other fields.10 Steinel reported that while only 3,018 graduate music degrees were awarded to women in 1972, this number had increased to 7,205 by 1988.11

Block noted only minor improvements in the status of women on music faculties during the period 1976-1986 even though the pool of qualified female candidates had greatly increased. She surmised that the reasons for the continued scarcity of women at higher ranks on music faculties might therefore be attributed to long-standing discriminatory practices rather than a lack of qualified women.12

Weaver surveyed Big Ten Conference universities regarding faculty gender, rank and salary and found inequities in both rank and salary based on gender. She found that females were more equally represented at lower ranks, but that as rank progressed the proportion of males increased. Women faculty were also found to have median salaries below overall median salaries at all ranks. This was especially true at the assistant and full professor levels.13

Method

This study analyzed music faculties using the 1993-1994 Directory of Music Faculties in Colleges and Universities, U.S. and Canada compiled by The College Music Society.14 The study population consisted of all U.S. four-year and graduate institutions included in the Directory who listed faculty above the rank of lecturer (N=1,101). Institutions who listed faculty without designating rank, two-year institutions and community colleges were excluded from the study (N=707). Each of the study institutions was analyzed to determine the exact number of tenure-track employees who held the rank of Assistant Professor, Associate Professor, and Professor. Females serving as adjunct, part-time, emeritus, lecturer, instructor, graduate assistant, and artist-in-residence faculty from each of the institutions (N=19,582) were also included in the study only for comparisons as a non-tenured "other" group.

For each of the study institutions, female faculty were then identified by rank and level of education using given name recognition. Female names included those listed in American Given Names, by George Stewart, and The Jonathan David Dictionary of First Names, by Alfred Kolatch. Unusual or foreign names, listings which included only first name initials, and names which may be either male or female (e.g. Billie, Caroll, Chris) as listed in the above references, were assumed to be male. To insure accuracy in the identification process, a random check of identified females in ten institutions was completed by two outside researchers and checked via telephone with the institutions. Interjudge reliability was determined to be acceptable (r=.96).

A comparison of remaining faculty (N=11,077) within the three ranks was then made to determine the current status of music faculty by gender and rank. Data on specific subject assignment categories and the level of education achieved by female music faculty was compiled. Subject assignments for females identified in the study were then correlated to listings by six subject areas in the Directory.

Results

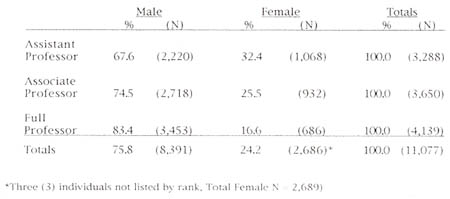

Full-time female music faculty comprised only 24% of all faculty in the study institutions, well below the 33% statistic for academic females nationally. As indicated by the research in other areas, females on music faculties also hold lower ranks than their male counterparts with only 17% of professor ranks being occupied by women. Unlike the national trend in other areas, males in the present study also dominated lower ranks with 68% of all assistant professor and 75% of all associate professor positions in music being held by men (see Table 2).

Table 2. Distribution of Music Faculties 1993-1994 by Gender and Rank

A majority of all female music faculty (N=2,689) in the study had earned doctoral degrees (49%, N=1,320) or master's degrees (44%, N=1,194). A small number of females were reported with only a bachelor's degree or diploma (3%, N=102). This reflects the rising standard in the job market in academia regarding job requirements as well as the increased number of advanced degrees awarded each year. Degree listings were not provided for the remainder of females (3%, N=73) in the study.

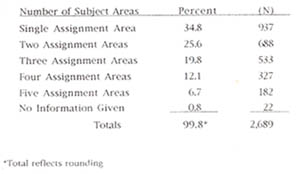

The Directory lists faculty members by as many as five assigned subject areas. A total of 34.8% (N=937) females in the study were determined to be assigned to only one subject area while 7% were assigned to five subject areas (N=182) (See Table 3).

Table 3. Distribution of Female Tenure-Track Music Faculty 1993-1994 by Number of Assignment Areas

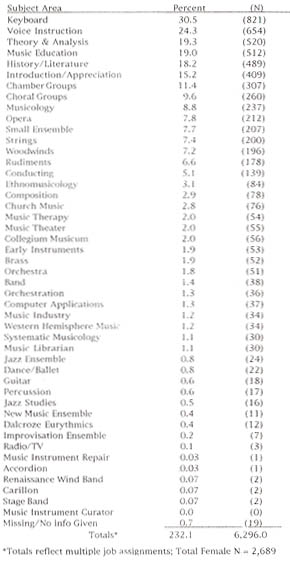

Within the female population on music faculties, job assignment areas were spread across forty-five of the forty-six areas listed in the directory. The distribution of females by number of subject assignments showed that the highest number of women was assigned to only one subject area (34.8%) followed by two subject areas (25.6%) and three subject areas (19.8%). The greatest number of females were found to be teaching in the areas of keyboard (30%), voice (24.4%), theory and analysis (19.3%), and music education (19%). No females in the study were listed as music instrument curator (see Table 4).

Table 4. Distribution of Female Tenure-Track Music Faculty 1993-1994 by Area

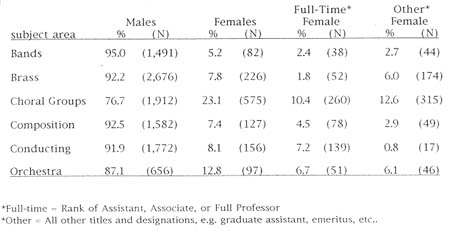

Six subject areas were selected for gender comparison—Bands, Brass (trumpet, horn, trombone, low brass), Choral Groups, Composition, Conducting, and Orchestra. Full-time females in all six areas were found to be faring poorly in comparison to their male colleagues (See Table 5).

Table 5. Gender Distribution of Music Faculties 1993-1994 by Selected Subject Areas

Summary and Discussion

The results of the present study illustrate that although female faculty have made progress since the enactment of Title VII in 1972, a significant gender gap exists in the employment of females on college and university music faculties. The Directory of Music Faculties in Colleges and Universities 1993-94 lists 30,582 faculty in all institutions and reports that 33.6% (N=10,282) of these positions are held by women. A total of 7,673 females are listed in the Directory but excluded from the study. This means that almost 75% of all females on higher education music faculties continue to be at two-year institutions, community colleges, or in part-time, unranked positions. Since, as Renton reported, females account for 23% of advanced degrees in music and this percentage is almost exactly the percentage of full-time female faculty nationally (24%), we may hypothesize that full-time employment for females in higher education is not normally possible without an advanced degree.15 Further research is needed to investigate the correlation between level of education and faculty rank for both males and females.

If Trollinger and other researchers are correct in their view that musical pursuits, more so than other fields of study, are stereotyped as feminine, it is perhaps even more confusing to find females so under-represented in college and university music faculties since the opposite would reflect the stereotype. Since future interest in music is initiated during childhood and nurtured through school experiences taught primarily by males, gender discrepancies found in the influential role models in public school music teaching may help explain the stereotypes that develop as students progress through the educational process and ultimately choose a vocation.

Graduate students are frequently counseled to be prepared to teach outside of their primary field of study during entry level positions. No information is available on the number of female faculty assigned to teach more than five subject areas, since the Directory limits this information. Further research is needed to determine if the same statistics hold true for males and non-tenure-track females and how closely related second subject areas are to the major field of study. Several of the subject areas might be grouped by similarities to simplify comparisons in future research (e.g. Rudiments + Theory/Analysis; Jazz Ensemble + Jazz Studies).

Of the tenure-track females in the present study, the top two areas of employment are keyboard (31%) and vocal instruction (24%). Other subject areas seem sparsely populated in comparison. More than 95% of all females are assigned to only fifteen of the forty-six areas.

The gender percentages in presumably influential role models present in secondary music programs in the public schools have not transferred to higher education. Although 57% of all secondary public school choral conductors are female, only 10% are tenure-track females at the university level. This disparity is even more pronounced in the instrumental area where 20% of secondary public instrumental teachers are female yet only 2% are tenure-track female college band directors.

Related research regarding instrument preferences and sex-stereotypes16 which suggests that brass instruments are perceived primarily as male is supported by the results of the present study. University faculty teaching brass instruments in this study are overwhelmingly male (92%).

Research efforts on the effects of maturation on musical abilities have implied that although females show significantly better musical abilities and higher interest at early ages, males may in effect "catch up" as they grow older.17 Further research is needed to determine the extent of this effect, if any, on skill development or motivation which might explain subsequent gender discrepancies in higher education.

An additional explanation for bias, as Betty Atterbury surmises, is the problem created by women who attempt to maintain demanding female roles within the family while also pursuing traditionally male full-time positions in academia. She points out that attempting to be "superwomen" can lead to stress and burn-out, creating the perception in male-dominated academia that women are unable to handle academic assignments and the long hours associated with the pursuit of creative works and tenure.18

The numbers and salaries of female faculty are only a small portion of the gender issue. Discriminatory perceptions or "micro-inequities" can ultimately affect every aspect of a female faculty member's working environment.19 Sandler includes in this category, the following behaviors:

1. Focusing on a woman's appearance and other personal attributes rather than on accomplishments.

2. Addressing women by social terms such as "sweetie", "dear", or "young lady".

3. Focusing undue attention on women's personal lives.

4. Presuming that the husband is the primary contributor.

5. Expecting women to behave in typically feminine ways.

6. Downgrading women's accomplishments when equal or superior to males.

7. Assigning women heavier workloads.

8. Refusing to collaborate with a female colleague.

9. Discrediting or trivializing work on women's issues.20

Viewed individually, these micro-inequities may be only minor irritations, but collectively they serve to undermine the confidence and productivity of female faculty who must expend time and energy coping and countering this discrimination. As this researcher has noted, it appears that women must be "twice as good" as male colleagues to look "as good."

Reversing this phenomenon will require additional research to identify underlying causes and successful interventions. Perhaps as the primarily all-male faculty reaches retirement age and is replaced, we will see the gender gap diminish further. Annual status reports should be disseminated to all institutions to increase awareness and assess progress. Female graduate students need to receive guidance on feminist issues in higher education, which will enable them to develop strategies for combatting the discrimination in salary and promotion and micro-inequities they may face as future members of academia.

The Directory is a substantial resource but contains numerous errors and omissions which hindered the goals of this particular study. It would be helpful for subsequent editions to encourage institutions submitting updated information to be more conscientious about accuracy and include a category specifying gender for all faculty.

Affirmative action is in crisis across the United States, as witnessed by the recent abolishment of policies protecting gender and race quotas in public educational institutions in the State of California. Research documenting gender imbalances and examining the extent to which they are the result of discriminatory practices is essential to the future of women musicians in American higher education.

References

______ The NEA 1995 Almanac of Higher Education. Washington, D.C.: National Education Association, 1995, 14.

Abeles, Hal. and Porter, Susan. "The sex-stereotyping of musical instruments," Journal of Research in Music Education 26/2, (1990), 65-75.

Atterbury, Betty. "What do women want?" The Quarterly Journal of Music Teaching and Learning (Winter, 1993), 100-104.

Block, Adrienne. The Status of Women in College Music, 1986-87: A Statistical Report. College Music Society, 1988.

Delzell, Judith and Leppla, David. "The effects of musical discrimination training in beginning instrumental music class," Journal of Research in Music Education 37 (1978), 21-31.

Directory of Music Faculties in Colleges and Universities, U.S. and Canada 1993-94. Missoula, MT: College Music Society, 1994.

Fairweather, James. "The value of teaching, research, and service," The NEA 1994 Almanac of Higher Education. Washington, D.C.: National Education Association, 1994, 39-58.

Gray, Mary. "Using regression to study faculty salaries," Thought and Action, 7/2 (191), 55-100.

Kolatch, Alfred. The Jonathan David Dictionary of First Names. Middle Village, NY: J. David Publishers, 1980.

Neuls-Bates, Carol. The Status of Women in College Music: Preliminary Studies. Manhattan, KS: Ag Press 1976.

Renton, Barbara. The Status of Women in College Music: 1976-1977: A Statistical Report. Boulder, CO: College Music Society Report, Number 2, 1980.

Sandler, Bernice. "The campus climate revisited: Chilly for women faculty, administrators, and graduate students," Glazer, Judith; Bensimon, Estela and Townsend, Barbara, Women in Higher Education: A Feminist Perspective. Needham Heights, MA: Ginn Press, 1993.

Steinel, Daniel. (Ed.) Data on music education. Reston, VA: Music Educators National Conference, 1990.

Stewart, George. American Given Names. New York: Oxford University Press, 1979.

Trollinger, Laree. "Sex/Gender research in music education: A review," The Quarterly Journal of Music Teaching and Learning (Winter, 1993), 22-39.

Weaver, Molly. "A survey of Big Ten institutions: Gender distinctions regarding faculty ranks and salaries in schools, divisions, and departments of music," The Quarterly Journal of Music Teaching and Learning (Winter, 1993), 91-99.

1Atterbury, Betty. "What do women want?" The Quarterly Journal of Music Teaching and Learning (Winter, 1993), 100-104.

2The NEA 1995 Almanac of Higher Education (Washington, D.C.: National Education Association, 1995), 14.

3Sandler, Bernice. "The campus climate revisited: Chilly for women faculty, administrators, and graduate students," Glazer, Judith; Bensimon, Estela and Townsend, Barbara, Women in Higher Education: A Feminist Perspective (Needham Heights, MA: Ginn Press, 1993).

4Ibid., p. 175.

5Gray, Mary. "Using regression to study faculty salaries," Thought and Action 7/2 (1991), 55-100.

6Fairweather, James. "The value of teaching, research, and service," The NEA 1994 Almanac of Higher Education (Washington, D.C.: NEA Publishing, 1994), 39-58.

7Trollinger, Laree. "Sex/Gender research in music education: A review," The Quarterly Journal of Music Teaching and Learning (Winter, 1993), 22-39.

8Leonhard, Charles. Status of Arts Education in American Public Schools (Urbana, IL: Council for Research in Music Education, 1991).

9Renton, Barbara. The Status of Women in College Music: A Statistical Report (Boulder, CO: College Music Society Report, Number 2, 1980).

10Neuls-Bates, Carol. The Status of Women in College Music: Preliminary Studies (Manhattan, KS: Ag Press, 1976).

11Steinel, Daniel. (Ed.) Data on Music Education (Reston, VA: Music Educators National Conference, 1990).

12Block, Adrienne. The Status of Women in College Music, 1986-87: A Statistical Report (College Music Society, 1988).

13Weaver, Molly. "A survey of Big Ten institutions: Gender distinctions regarding faculty ranks and salaries in schools, divisions, and departments of music," The Quarterly Journal of Music Teaching and Learning (Winter, 1993), 91-99.

14Directory of Music Faculties in Colleges and Universities, U.S. and Canada 1993-94 (Missoula, MT: College Music Society, 1994).

15Renton, Barbara. The Status of Women in College Music: 1976-1977: A Statistical Report (Boulder, CO: College Music Society Report, Number 2, 1980).

16See Abeles, Hal. and Porter, Susan, "The sex-stereotyping of musical instruments." Journal of Research in Music Education 26/2 (1990), 65-75, and Delzell, J. and Leppla, D. "The effects of musical discrimination training in beginning instrumental music class," Journal of Research in Music Education 37 (1978), 21-39.

17As cited in: Trollinger, Laree. "Sex/Gender research in music education: A review," The Quarterly Journal of Music Teaching and Learning (Winter, 1993), 22-39.

18Atterbury, Betty. "What do women want?" The Quarterly Journal of Music Teaching and Learning (Winter, 1993), 100-104.

19Sandler, Bernice. "The campus climate revisited: Chilly for women faculty, administrators, and graduate students," Glazer, Judith; Bensimon, Estela and Townsend, Barbara, Women in Higher Education: A Feminist Perspective (Needham Heights, MA: Ginn Press, 1993).

20Ibid., 178-180.