"But I don't hear it that way!" This phrase is used often by students, and on occasion by theory instructors themselves, to object to a particular analysis. When one of our colleagues uses that phrase, we expect it to be followed by an analytical interpretation different than the one s/he has just been presented. All too often, however, when one of our students uses the phrase, we assume that it is based on some sort of aural naiveté. We may even take the phrase as a signal that the student has some misunderstanding that needs to be corrected. I would like to suggest here that theory instructors consider an alternate response to students' use of the phrase in the theory class, and treat it as an opportunity for student-generated learning.

Even when the phrase indicates a wrong answer on the part of the student, a more open-minded response can change the atmosphere in the class. For example, when writing the answer to a given melodic dictation on the board I have heard students say the ear-training variation of the phrase, "but I didn't hear that." One's initial reaction might be to respond, "Of course you heard that—the whole class heard the same melody, you merely thought about it the wrong way." While such a response may be true, in many cases it immediately stops any desire on the part of the student to learn the difference between what s/he heard and what s/he thought s/he heard. I have found it much better to ask the student, "What did you hear?" (One might also ask "what did you think you heard" or "what did you write down as the melody" if there is the fear of encouraging the belief that each student could have heard a different melody.) Writing the student's melody on the board below the correct solution and performing both melodies allows everyone in the class to see and hear difference between them. A discussion or a series of drills can follow to focus on any problems this student (or others in the class) may have had. Even though everyone in the class knows that the student's melody is a wrong answer, they realize that it has become the generator of the class discussion. Other students become much more willing to share responses, and it is easier for the instructor to find and correct student problems.

The "but I don't hear it that way" phrase arises much more frequently in theory classes, especially during harmonic analysis. While it is difficult to justify a mislabeled chord with the phrase, there are times that the phrase introduces a valid differing point of view. The following example offers a simple illustration. Most students will label the third chord in the first measure as a root position supertonic triad and consider the tenor c-sharp as an unaccented passing tone.1

Example 1. Bach, Chorale 367, mm. 1-2

Occasionally a perceptive student will respond with the "but I don't hear it that way" phrase and will want to label the chord as a first inversion leading tone triad, considering the tenor B as an accented passing tone.

The student-generated discussion that ensues could be a high-level one that involves much more than chord labeling. Addressing the function of the chord in its immediate context—a passing chord between I6 and I—might lead the students to discover that the first five chords represent an opening prolongation of the tonic. By calling their attention to the subdominant triad in measure one, I would help them discover how it should be understood as a neighboring chord to the tonic rather than as a dominant-preparation chord. Students who typically consider the subdominant and supertonic triads as having similar dominant-preparation functions may begin to discuss if these two chords can also have a similar tonic-prolongation function. From previous class discussions, some students will observe that the vii more typically functions as a passing chord. Inevitably some perceptive student will point out that the chord on beat three of measure one sounds different than the chord on beat one of measure two—a first inversion supertonic seventh chord. This observation may lead to the discovery that, at the level of the phrase, the opening tonic prolongation ends as this chord signals the cadence.2

more typically functions as a passing chord. Inevitably some perceptive student will point out that the chord on beat three of measure one sounds different than the chord on beat one of measure two—a first inversion supertonic seventh chord. This observation may lead to the discovery that, at the level of the phrase, the opening tonic prolongation ends as this chord signals the cadence.2

At some point a student will offer the compromise of labeling two chords on the third beat of measure one. This suggestion could initiate a discussion of harmonic rhythm. If the students are instructed to place a single Roman numeral beneath this chord, perhaps someone will counter with the argument that s/he is being forced to make a decision (ii or vii ) that Bach did not make because his eighth-note motion actually sounds both chords. While it may be rare, occasionally someone will observe that ii-vii

) that Bach did not make because his eighth-note motion actually sounds both chords. While it may be rare, occasionally someone will observe that ii-vii -I—a progression at the eighth-note level—anticipates the following ii

-I—a progression at the eighth-note level—anticipates the following ii -V-I progresion at the quarter-note level in measure two.

-V-I progresion at the quarter-note level in measure two.

Although it is uncommon for all of the preceding hypothetical class discussion to unfold entirely in the manner presented above, I have had many of these types of discussions in my freshman and sophomore theory classes. At one time or another, students in these classes made most of the observations that appear above. If a student utters the "but I don't hear it that way" phrase and I turn to the rest of the class and ask them what they think; the type of discussion above almost always follows. It is during these types of class meetings that the theory professor takes on the role of facilitator rather than instructor.

In the remainder of this article, rather than present numerous isolated anecdotes that provide examples of student-generated learning in my classroom, I would like to present a single example for a more in-depth examination. The example, a passage from the middle of a Schumann song, is part of an assignment that I made in my chromatic harmony class—a second semester freshman or first semester sophomore class required of all undergraduate music majors. While going over the assignment in class, a student stopped me with the "but I don't hear it that way" phrase. The next section of this article will examine exactly what transpired in the classroom. The final section of this article will examine what I could have done to continue and expand upon the opportunity presented by this phrase.

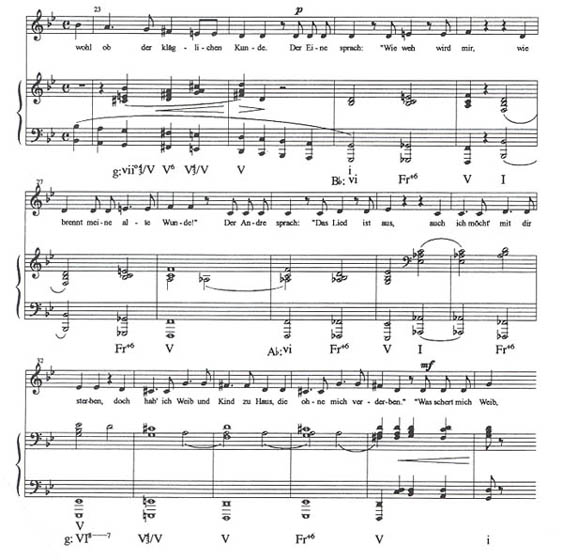

The assignment for that day included, among other musical excerpts for harmonic analysis, measures 23-37 from Robert Schumann's Die beiden Grenadiere, Op. 49, No. 1. (See Example 2.) The following instructions appeared with the passage: "This excerpt begins and ends in g minor, but it contains modulations to two other keys (or tonicizations of two other chords). How do these keys relate to the 'parent' tonality of g minor?"3 From the placement of the assignment in the workbook (in the first of two chapters on augmented sixth chords4) and from the directions preceding the passage, the desired chord labeling (as it appears in Example 2) is obvious.5

Example 2. Schumann, "Die beiden Grenadiere," mm. 23-27

The "but I don't hear it that way" issue arose when several students claimed to hear the areas tonicized as F major and E-flat major rather than B-flat major and A-flat major. Each of these students knew (and had produced) the analysis that was "expected," but each of them expressed the frustration that the Roman numeral analysis that they wrote (and knew was "right") did not match their aural experience of the passage. My response to these students (and my invitation to the rest of the class) was, "Let's find out why you hear it the way you do."

When challenged to defend why they heard F and E-flat as the tonicized keys (rather than B-flat and A-flat), these students were able to offer several concrete reasons. They argued that if B-flat and A-flat were considered tonics, the phrases analyzed would end with half cadences that are never "answered" with authentic cadences in those keys. The chords that followed the F major triad in measure 26 and the E-flat major triad in measure 30 did not sound like tonic chords to them, but rather subdominant chords that lead to repetitions of authentic cadences in F major (measures 27-28) and E-flat major (measures 31-32).

Again I challenged them to tell me why they heard the cadences the way they described them, and again they produced concrete musical reasons. A reading of the passages in F major and E-flat major can be defended with a "metrical" argument—the tonic chords are always on the downbeats of measures and the authentic cadences always occur "across the barline." A reading of the passages in F major and E-flat major also allows a "diatonic" reading of the melody. The melody in these passages would consist of the diatonic scale degrees  -

-  -

-  rather than the chromatic

rather than the chromatic  -

-  -

-  in B-flat major and A-flat major. This melodic observation led the students to compare the chords beginning measures 25 and 27. An F-major interpretation of these measures demonstrates the possibility of harmonizing scale degree

in B-flat major and A-flat major. This melodic observation led the students to compare the chords beginning measures 25 and 27. An F-major interpretation of these measures demonstrates the possibility of harmonizing scale degree  with either ii (in measure 25) or IV (measure 27) and permits a harmonic analysis in which the same melodic idea (

with either ii (in measure 25) or IV (measure 27) and permits a harmonic analysis in which the same melodic idea ( -

-  -

-  ) is harmonized with similar function chords. (The same observation holds true for measures 29 and 31 in the key of E-flat.)

) is harmonized with similar function chords. (The same observation holds true for measures 29 and 31 in the key of E-flat.)

Yet another compelling argument presented by the students was based on the pitches introduced in the second halves of measures 28 and 32. In the first instance the inner voice A of the F major triad becomes A-flat. Whether analyzing this passage in B-flat major or F major, one would describe the A-flat as a result of modal mixture. The students observed that the lowering of the third of the chord through modal mixture is much more likely to occur in the tonic triad than the dominant triad. In the second instance the top voice E-flat of the E-flat major triad descends to D. If this passage were in the key of A-flat, the D-natural would have to be a chromatically altered pitch. A reading of this passage in the key of E-flat, however, allows for a diatonic interpretation of the D. In both cases, what follows the F major and E-flat major triads seems to confirm them as tonic triads rather than dominant triads.6

After informing the students that they had convinced me that analyzing these passages, as toncizations of F major and E-flat major was equally valid to analyzing them in B-flat major and A-flat major, I suggested that we discuss the implications of their analysis. The first issue that I asked them to address concerned the chords prior to the F major and E-flat major triads. I asked them what Roman numeral/inversion symbol I should place under the second chords of measures 25, 27, 29, and 31. I explained to them that if I analyzed these passages in B-flat major and A-flat major, I could label these chords as French augmented sixth chords in those keys. The students knew that if the chords preceding those in question were supertonic or subdominant chords and the ones following them were tonic chords, the chords in question must be dominant function chords. After some discussion of the function and attempting to view the structure as superimposed thirds, the class decided that it must be some altered version of a dominant seventh chord. On their own the class had discovered the dominant seventh chord with lowered fifth, several weeks ahead of when I had scheduled that topic! This discussion then led the class to compare the function of the various augmented sixth chords with the family of secondary dominants applied to the dominant. The class seemed to have a much better understanding of the chromatic principles that we had been working on for the previous two months.

The next issue that I asked the students to address involved key relationships. If the passages in question were analyzed in B-flat major and A-flat major, the tonicized keys would be the relative major and the Neapolitan. If the passages in question were analyzed in F major and E-flat major, the tonicized keys would be the subtonic and the submediant. While all of the students acknowledged that it seemed to work out "neater" with the first interpretation (in terms of the topics that we had been studying in class), they were quick to point out that both of the latter keys were closely related keys and only one of the former keys was a closely related key.7 Since all four of these key areas could logically appear in this song, we decided to examine the context of this passage to see if it could provide any help.

During this particular class we did not have the music or recording of the complete song, so we could not determine how measures 22-37 related to what preceded and what followed. We could, however, try to relate the tonicizations in measures 25-28 and measures 29-32 to the measures that preceded and followed these toncizations. The class decided that the overall harmonic motion of the passage could be viewed as a motion from the tonic in measure 22 to an authentic cadence from measure 36 to measure 37. I asked the class to treat each tonicized area as a prolonged harmony to determine if either one made more sense as a large-scale progression. We decided that either progression was possible. With the tonicized keys of B-flat major and A-flat major, the harmonic progression would be I-III- -V-I.8 With the tonicized keys of F major and B-flat major, the harmonic progression would be I-VII-VI-V-I. Several students again observed that the first harmonic progression worked out "neater" in terms of what we had been studying, but almost everyone in the class felt that the second progression (when played on the piano) sounded more like the actual song. One of the students who opted for the "neater" analysis observed that even within the tonicized keys of B-flat and A-flat the "goal" chords were the dominants of those keys and the second progression above emphasizes that relationship.

-V-I.8 With the tonicized keys of F major and B-flat major, the harmonic progression would be I-VII-VI-V-I. Several students again observed that the first harmonic progression worked out "neater" in terms of what we had been studying, but almost everyone in the class felt that the second progression (when played on the piano) sounded more like the actual song. One of the students who opted for the "neater" analysis observed that even within the tonicized keys of B-flat and A-flat the "goal" chords were the dominants of those keys and the second progression above emphasizes that relationship.

I then suggested to the class that we try to think about what other aspects of the song might help our decision. Before we could consider any other topics, one of the students who was tiring of our detailed discussion about sixteen measures of music challenged me to justify how such an approach might help her understand the music any better. Since this student happened to be a singer, I asked her what she thought about when preparing to perform a song. She responded that one of the first things she thinks about is the text, and criticized our discussion for not mentioning the text at all. I thanked her for making that observation and told the class that we should attempt to relate our harmonic discussion to the setting of the text.

Before we examined the text, however, I asked the class how the two harmonic interpretations might affect their performance of the passage. After a comparison of these two analyses, the class decided that the main difference between the B-flat major/A-flat major interpretation and the F major/E-flat major interpretation was the cadence. The first interpretation created a series of half cadences and the second interpretation created a series of authentic cadences. The class thought that the performance should emphasize either the incompleteness (of the half cadences) or the completeness (of the authentic cadences). Now we were ready to address the text.

The passage of the song that we had in class set portions of three stanzas of a nine-stanza poem.9 Below is a translation of these three stanzas in their entirety. The bracketed portions were not available to use in that class, and the italicized portions are the lines set in the two tonicized areas.

[Da weinten zusammen die Grenadier']

Wohl ob der kläglichen Kunde.

Der Eine sprach: "Wie weh wird mir,

Wie Brennt meine alte Wunde!"

Der Andre sprach: "Das Lied ist aus,

Auch ich möcht' mit dir sterben,

Doch hab' ich Weib und Kind zu Haus,

Die ohne mich verderben."

"Was schert mich Weib, [was schert mich Kind,

Ich trage weit besser Verlangen:

Lass sie betteln gehn, wenn sie hundgrig sind,

Mein Kaiser, men Kaiser gefangen!][Then the grenadiers wept together]

At those hard tidings,

One said: "It goes ill with me,

How my old wound is burning!"

The other said: "The song is sung,

Would I could die with you,

Without me they would perish."

But I have wife and child at home,

"What are wife [and child to me?

I have far nobler desires;

Let them beg if they are hungry,

My Emperor, My Emperor captured!]10

Considering the text added a new dimension to our discussion of the harmony and enticed a few additional students to enter into the discussion. The class was divided on whether the italicized text above should be performed with "statement-ending" authentic cadences or "needing continuation" half cadences. After a very lively discussion the class seemed to reach some consensus. Most of the students felt that the F major/E-flat major, authentic cadence interpretation was the better solution. They thought that the italicized text included statements (rather than questions) that should conclude with authentic cadences. The fact that these cadences were not in the tonic, however, provided the "harmonic incompleteness" that led the listener to the next passage of text.

Having reached some degree of closure we ended our discussion of this passage. The discussion lasted much longer than I had anticipated, and we did not have the opportunity to discuss all of the previous night's assignment. We had, however, covered much more material in much more depth than I had anticipated. And, most importantly, the discussion was lively and the learning was student-generated. It would be nearly impossible to plan for these types of spontaneous, student-generated class discussions. After reflecting on what transpired in that class, I began to think about how I could take advantage of the discussion in a subsequent class meeting. In the final section of this article, I would like to present some ways that I might have continued and expanded upon the enthusiastic class discussion.

In the class session in which this Schumann song was discussed, the students considered only the text of the passage we analyzed harmonically. A more thorough treatment of the text of the song could have occurred at the beginning of a follow-up class session. The poem is a ballad by Heinrich Heine (1797?-1856). That simple observation might require some brief discussion of the poet and the term "ballad." I would probably want to take into class the poem, titled Die Grenadiere by Heine, and a good translation side-by-side. The story of this ballad is about

two soldiers returning from Russian captivity after Napoleon's ill-started winter campaign in 1812, to learn that the Emperor had been captured and his valiant army decimated.11 Badly wounded, one of the grenadiers asks his companion to take his body back to France and bury him in French soil. The poem rises almost to ecstasy as the wounded warrior envisages the Emperor riding over his grave, from which he is sure that he will rise to guard his leader.12

In the discussion of Heine and this poem, the students might find it interesting that he "was always an enthusiastic supporter of Napoleon, who for him stood for progress, liberalism, tolerance of religious minorities (not, however, of the majority), and general enlightenment. Even toward the end of Napoleon's career, when he emerged as something less than a benefactor, Heine retained his attitude of hero worship."13 Also worthy of note is the fact that Heine lived much of his life in Paris and thought that "French Culture was infinitely superior to German; many of his poems praise the former at the expense of the latter, which he once pictured as a lumbering dancing bear."14

I would also want the students to hear and have the music for the whole song. Discussing the musical context of the passage in question might affect the students' interpretation of the passage. On the first hearing of the entire song, the class would probably want to discuss Schumann's use of the Marseillaise for the setting of the last two stanzas. Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau refers to "the triumphal entry of the 'Marseillaise' at the end" as "the high point of the piece."15 Wagner, who also set the same Heine poem, used the Marseillaise at the end.

When Wagner heard of Schumann's composition he wrote an anxious letter from Paris. "I hear that you have set Heine's Grenadiers to music and that it ends with the "Marseillaise." Last winter I set the same poem to music and also used the "Marseillaise" as the conclusion. That is of some significance!"16

Jack Stein writes that Schumann's adaptation of the Marseillaise is brilliant and causes the song to culminate "in a highly theatrical, indeed sensational, vision of the dying French soldier who expects to rise from his grave and join Napoleon as he rides once more to victory."17

While the previous observations are interesting and serve to provide a historical context in which to consider this song, they do little to aid our understanding of the harmony of the passage in question. A logical next step would include a study of the formal structure of the song, how the form of the song relates to the structure and meaning of the poem, and an examination of how the passage under consideration relates to the structure of both the song and the poem.

The passage quoted in Example 2 consists of sixteen measures (measures 23-37) of an eighty-two measure, through-composed song. As Fischer-Dieskau observes, however, "within the 'through-composed' form of the piece, there are hints at strophic, repeated patterns."18 While the melodic and harmonic material from measures 25-36 are not used anywhere else in the song, the texture of these measures (half-notes in the piano accompanying a recitative-like melody in the voice) is found in measures 11-18 and ornamented in measures 45-52.19 This half-note, homophonic texture is also used in the piano during the last six measures. The measures that begin Example 2 (measures 23-24) are an exact repetition of measures 5-6, 9-10, 39-40, and varied slightly in measures 43-44. Additionally measure 18 is a slightly varied form of measure 24. Taking into consideration the preceding repeated textures and melodic/harmonic patterns, one might outline the form of the song in the following manner:

measures

1-9

10-18

19-24

25-36

37-44

45-52

53-60

61-78

78-82form

A: funeral-march character

B: recitative-like character

A

B'

A

B

march-like accompaniment/ recitative-like melody

Marseillaise melody

Coda: piano alone with "B texture"key

g

g (Bb/c)*

g

g (Bb/Ab) or g (F/Eb)

g

g (Bb/c)

g

G

Gpoem stanza/lines

1

2

3/1-2

3/3-4 & 4

5

6

7

8-9* Keys in parentheses indicate brief tonicizations.

Given the formal structures of the song and the poem, I would then expect the students to notice that the song's musical form seems to coincide with the poem's form with one exception. The beginning of stanza three is set with the "A texture" and the end of stanza three is set with the "B texture." I would also expect the students to notice that this occurs during the passage that began our study of this song. I would then point out that stanza three is a significant turning point in the song. During the first two and one-half stanzas of the poem, the narrator is "speaking." During the third and fourth lines of the stanza, one of the grenadiers speaks for the first time. This is the only stanza that is divided between narrator and grenadier. The fourth stanza is the only stanza in which the second grenadier speaks; during the remainder of the poem (stanzas five through nine) only the first grenadier speaks. I would remind the students that the music of measures 25-35 is used nowhere else in the song and suggest that since this passage sets the only text in which both grenadiers speak, Schumann might have based his compositional decision on a close reading of the poem.

The class might then consider other elements of the form and harmony and their relationship to the text of the poem. Some of the class observations should be the same as those in James Hall's discussion of this song:

The effect of Schumann's setting is that of music which is constantly shaping itself to fit the dramatic narrative, that is, as durchkomponiert dramatic ballad. In truth the strong and martial theme, A, used to introduce the characters, and its musical complement, B, m. 10-19, with accompaniment in grave-appearing half-notes, return, and with slight variation seem meant exactly for the conversation of the soldiers. Note the variation of the accompaniment as A enters the third time, "Was schert mich Weib;" the growing intensity is marshaled by increasing speed, the new triplet figuration in the accompaniment of B, and finally by volume. Repeated four times and serving as transition is the two-measure phrase, m. 53-54, with its syncopated accompaniment of but a measure's length, the bass of the second an octave higher.

Then as a symbol of French patriotism, Schumann has the grenadier swear his loyalty to the tune of La Marseillaise, the accompaniment marching along in sturdy column-like chords, and the major mode most brilliant. Twice woven into this is an extension of the sixteenth-note motive of m. 2. Probably Schumann had in mind this climax and made his first theme such that the introduction of the national hymn seems musically inevitable. The last six measures offer another illustration of the way in which the musician reads between the lines of the poet. There is nothing in Heine's poem to indicate anything other than a heroic ending, as the soldier visions his Emperor again the victor; and thus it is usually treated by the singer-actor. But the soldier has twice told us that his time is near. He has been buoyed up by his excitement, but his strength is not sufficient. His last phrase Schumann marked not allargando, but ritardando. This is not a heroic ending of grandeur, but a transition and decline to the slow, sustained, drooping chords of the epilogue, whose last two measures are adagio.20

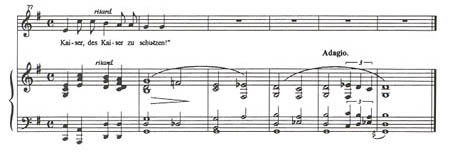

In addition to the last six measures offering "another illustration of the way in which the musician reads between the lines of the poet," these measures would also provide some harmonic interest for the theory class. As one can see in Example 3, early in the coda of this song there is an applied dominant of the subdominant. (See the second chord of measure 78.)

Example 3. Schumann, "Die beiden Grenadiere," mm. 77-82

What might interest the class is the fact that this applied dominant is an altered dominant seventh chord—a dominant seventh chord with lowered fifth. This is the same version of the dominant seventh chord that appears in measures 25, 27, 29, and 31 from the passage that originally began the class discussion. The chord in measure 78 appears in the same metric position (beats 3-4) and in the same half-note texture as the previous passage. The students might want to consider this passage in support of their F major/E-flat major interpretation of the earlier passage.

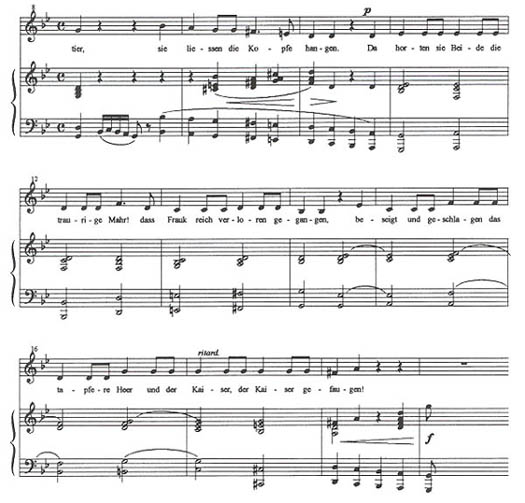

Additional support for the F major/E-flat major interpretation of measures 24-32 might be found by comparing this passage to the previous "B section" that has the same half-note accompaniment texture. The previous B section begins with a tonicization of B-flat major achieved by the chords IV -V

-V -I. (See measures 11-12 in Example 4.) One could argue that the tonicizations of these two passages are similar, with subdominant and dominant chords preceding the chord tonicized.

-I. (See measures 11-12 in Example 4.) One could argue that the tonicizations of these two passages are similar, with subdominant and dominant chords preceding the chord tonicized.

Example 4. Schumann, "Die beiden Grenadiere," mm. 8-18

Before leaving this song and returning the class to our more traditional approach to chromatic harmony, I would want to call their attention to the measures that begin Example 2 (measures 23-24) and remind them that these measures are an exact repetition of measures 5-6, 9-10, and 39-40, with a varied repetition in measures 43-44 and a varied repetition of the second measure in measure 18. I might suggest that the class examine the text of the poem set by these passages in the following manner:

measures

3-4

9-10

18

23-24

39-40

43-44line of poem

2

4

8

10

18

20last word of the line

gefangen

hangen

gefangen

Kunde

Verlangen

gefangen

I would point out to the students that "the rhyme with line 2 (gefangen: hangen) is repeated in 6, 8, 18, and 20."21 I would also want them to know that this is the only rhyme scheme that is repeated in the poem, so it is probably significant that Schumann set five of the six rhyming words with the same music. It is also interesting that the only time this music is not used to set one of the six rhyming words is in the passage that initiated the discussion of this song.

If I were able to spend an additional class period examining Schumann's Die beiden Grenadiere, I would hope that the students would have a better understanding of how Schumann's reading of a poetic text might have influenced his compositional decisions. I would also hope that they could see how a closer examination of the text and the complete song could provide insights that could influence analytical decisions of a passage within the song. Additionally, the students in this class would learn a valuable lesson seeing how their analytical conclusions can call into question the authority of the printed text.

It is unlikely that many of us would have enough time in an undergraduate core theory course to allow two or more class periods to continue to expand upon an enthusiastic class discussion in a manner that I have described here. What I would like to suggest here is that theory instructors consider an alternate response to the student use of the "but I don't hear it that way" phrase in the theory class, and treat it as an opportunity for student-generated learning. When the theory professor takes on the role of facilitator rather than instructor, the class discussion is almost always livelier and the students seem to have a much better (and more permanent) grasp of the material.

1I am considering here only the first phrase of this chorale harmonization and labeling the chords in the key of D major.

2The more perceptive students will notice that the tonic triad at the cadence has the same soprano and bass tones as the other tonic triads in the first phrase. This observation may lead to a discussion of levels of prolongation.

3Stephan Kostka and Dorothy Payne, Workbook for Tonal Harmony with an Introduction to Twentieth-Century Music, 4th ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2000), p. 223.

4Stephan Kostka and Dorothy Payne, Tonal Harmony with an Introduction to Twentieth-Century Music, 4th ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2000). See Chapter 23: Augmented Sixth Chords I and Chapter 24: Augmented Sixth Chords II.

5The harmonic analysis in Example 2 is the one provided by the textbook authors. See Stephan Kostka and Dorothy Payne, Instructor's Manual to Accompany Workbook for Tonal Harmony with an Introduction to Twentieth-Century Music, 4th ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2000), p. 135.

6What followed in class was a very brief discussion of "simplest interpretation." The class was interested in why we would prefer to think of (and hear) a passage as diatonic rather than chromatic. We tried to think of other examples where this concept applied. I played the pitches C followed by an A-flat on the piano and asked them to identify the interval. After they all agreed that it was a consonant minor sixth, I played an arpeggiated C augmented triad. Now they began to question the consonance of the outer interval and thought that it might be a dissonant augmented fifth. On the board, I wrote the pitches C, F-flat, and A-flat. I asked them why they did not continue to assume that the C to A-flat was consonant and the added pitch introduced a dissonant F-flat. We discussed that in each case they assumed the "simplest interpretation." This then led to a discussion of how the context determines our aural interpretation and then why in interval dictation the tritone cannot be identified more specifically. The students often learn a significant lesson in this type of tangential class discussion.

7We discussed as an aside how the key of the Neapolitan was closely related even if it did not fit into the textbook's definition of "closely related keys."

8The class had a brief discussion about the imperfect analogy of progressions involving key areas and progressions involving chords. In this chord progression, for example, one would expect a first inversion Neapolitan triad. Successive root position triads of these chords would be less likely.

9At the time of the class discussion we did not know the number of stanzas or how the text fit in with the rest of the poem.

10Text and translation from Robert Schumann, Heine-Lieder, performed by Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau and Jörg Demus (Deutsche Grammophon Gesellschaft 139110, 1966).

11One might discuss whether Schumann and Heine had different views of how badly the French army was defeated. For Heine the valiant army was "besieght und zerchlagen" (defeated and battered), while for Schumann the valiant army was "besieght und geschlagen" (defeated and "merely" beaten). This word is the only one changed by Schumann in his setting of Heine's poem.

12Kenneth Whitton, Lieder: An Introduction to German Song (London: Julia MacRae Books, 1984), p. 143.

13Elaine Brody and Robert A. Fowkes, The German Lied and Its Poetry (New York: New York University Press, 1971), p. 173.

14Whitton, Lieder: An Introduction to German Song, p. 143.

15Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, Robert Schumann Words and Musicthe Vocal Compositions, trans. by Reinhard G. Pauly (Portland, OR: Amadeus Press, 1988), p. 69.

16Ibid., p. 70. Wagner used a French translation of the poem. Fischer-Dieskau observes that Wagner "also used the 'Marsellaise' as its finale, but not so successfully as did Schumann" (p. 69).

17Jack Stein, Poem and Music in the German Lied from Gluck to Hugo Wolf (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1971), p. 104.

18Fischer-Dieskau, Robert Schumann Words and Musicthe Vocal Compositions, p. 69.

19Measures 45-52 are a varied repetition of measures 11-18. The chords used in both passages are exactly the same.

20James Husst Hall, The Art Song (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1953), p. 68.

21Brody and Fowkes, The German Lied and Its Poetry, p. 173.