John Harbison's Mirabai Songs are musical settings of six poems by an Indian princess, Mirabai Rathor, who lived during the first half of the sixteenth century.1 Written in 1982, the songs were originally conceived for soprano and piano, and later reworked in a version for soprano and chamber orchestra.2 Given the viewpoints related by the poems and their historical and present-day place in Indian society, as well as the nature of Harbison's musical settings, a study of these songs offers an opportunity for broad, interdisciplinary explorations in the music theory classroom. Focusing on the first three songs, this article will outline aspects of the poetry, its setting, and the interaction between text and music that might be discussed in an undergraduate class, along with possibilities for exploring the poems as windows to Indian culture, history, and feminist thought.

Mirabai lived in the northwestern region of Rajasthan, but she is considered a saint by people from all regions of India. Historical accounts of her life differ, perhaps because of the controversial nature of her actions, as well as the variety of perspectives from which her story has been told. Because significant spans of history lack any written records of Mirabai, and because the multiple written and oral traditions regarding her story vary considerably, there is no true historical biography of Mirabai.3 The following outline of Mirabai's biography is based on a combination of written versions and oral "retellings"of her story, including the songs frequently attributed to her.4

Mirabai was a religious person from childhood, owning a murti, or likeness of her god, Krishna, from perhaps as early as the age of five.5 In accordance with Indian custom, Mira's marriage was arranged by her family when she was a young woman.6

She was to marry the son of the ruler of a neighboring clan, but she objected, saying that she was already married to Krishna. Her mate was likely chosen, in part, for the purpose of strengthening political ties in the feudal society in which she lived. Most retellings of Mira's story agree that she was an unwilling participant in her wedding ceremony, and that she experienced the hostility of her parents-in-law when she arrived at their home, refusing to worship their god or to consummate her marriage. Her father-in-law demanded that she live in a separate area of the palace, where she worshipped Krishna privately. She also left the palace to worship and meet with holy men in the temples, and perhaps to mingle with low-caste people, offering them food and clothing. In this way, she broke the social rules of purdah, a practice in which a woman of a royal household is expected to remain veiled and is restricted in her movements outside the household.7

According to some versions of Mira's story, her husband died when she was still a young woman. She refused to commit sati, a practice in which a wife sits on the funeral pyre of her husband and is burned alive along with his body. Instead, she sang that since her real husband, Krishna, lives eternally, there was no reason for her to commit sati, a practice of widows.8 In addition to functioning as a verb, the term sati is also used as a noun, referring to a virtuous wife who is completely dedicated to her husband. Instead of the traditional view that a woman's earthly husband is her lord, Mira believed that ultimately, Krishna would be the "husband" and lord of all people, regardless of gender.9

Mira's family-in-law conceived various plots to murder her, acting to avenge the shame she had brought to them with her socially unacceptable actions.10 The rana [ruler] sent a cup of poison to her, claiming that it was holy water. She drank it, but was not injured, because the liquid was transformed into nectar through Krishna's intervention. At the ruler's command, a poisonous snake was delivered to her, but when she opened the basket containing it, she found a diamond necklace instead. Finally, the rana attempted to murder her with his own sword, but when he entered her chambers, he saw four different Miras, and so he left without attacking her, since he was unsure which one was real. These and other miracles included in the oral traditions of her life story are viewed as evidence of her status as a saint.11 After these attempts on her life, Mira left her family and travelled to pilgrimage sites considered sacred by the followers of Krishna, dancing and singing her songs of praise in the streets, as well as in the temples.

Years later, the rana sent priests to the city of Dwarka, in order that they might find Mirabai and ask her to return home. His motivations are not known. He may have wished to apologize to Mira and to reconcile with her, or he may have done this for political purposes: his men had lost many battles and some people felt that these military losses were occurring as punishment for his persecution of Mira. By this point, she had become famous as a religious figure, and so she could have been a valuable political asset. When the priests arrived, she refused to leave until they began fasting, and then she agreed to go with them only after she spent one more night in the temple. The priests waited outside, while Mira sang and danced for Krishna that night. When they entered the temple the next morning, they found only her clothing wrapped around her idol of Krishna, who had responded to her plea and incorporated her into himself.12

Mirabai practiced bhakti, or "devotion," a fervent type of worship that grew from the Vaishnava branch of Hinduism. Bhakti is sometimes described as a "passionate and intoxicating love" for a personal god that is "spontaneous yet cultivated through ritual and song."13 The bhakti movement developed in southern India in the seventh century, and it represents a shift from religious practice mediated by priests, who were often paid for their direct interventions with God on behalf of others, to a personal relationship between the human and the deity. The movement is also marked by a shift from the elite language of Sanskrit to local vernacular languages. Religious leaders were determined by their experience rather than heredity, and they included women and people of all classes. A primary tenet of the bhakti movement is the belief that all people are considered equal in the eyes of God, and thus traditional caste rules of purity are not acknowledged by the devotees.14

Bhakti is characterized by levels that describe metaphorically the human-divine relationship. Listing these in order of increasing strength in the bond between human and deity, they are a state of peacefulness, love of a servant, love of a friend, love of a parent, and erotic love.15 Thus, the highest form of worship is considered to be a mixture of the spiritual and sensual. The goal of bhakti is to experience increasingly greater depths of love for God, and the physical and spiritual desire of a woman for Krishna represents metaphorically the soul's desire for union with God.16 In discussing Mirabai's poetry, John Harbison has said that "the ambiguity between the sacred and the erotic . . . . is very important" and that relating to it is a significant aspect of singing this kind of text.17

The poems that serve as the basis of Harbison's songs describe the full range of Mira's emotions regarding Krishna, from her longing for his presence to her defiant defense of her own actions as one of his followers. The text of the first song, "It's True, I Went to the Market," is given below.18

"It's True, I Went to the Market"

My friend, I went to the market and bought the Dark One.

You claim by night, I claim by day.

Actually I was beating a drum all the time I was buying him.

You say I gave too much; I say too little.

Actually I put him on the scale before I bought him.

What I paid was my social body, my town body, my family body, and all my inherited jewels.

Mirabai says: The Dark One is my husband now.

Be with me when I lie down; you promised me this in an earlier life.

The poem reflects metaphorically the price Mirabai paid for Krishna, renunciation of her own royal status and exile from her family and from society in general: "What I paid was my social body, my town body, my family body, and all my inherited jewels." She also indicates that for her, no price is too great, that the "purchase" was a deliberate and even proud act, as it occurred by daylight, after "weighing" her decision, and while beating a drum—or done publicly and without shame.

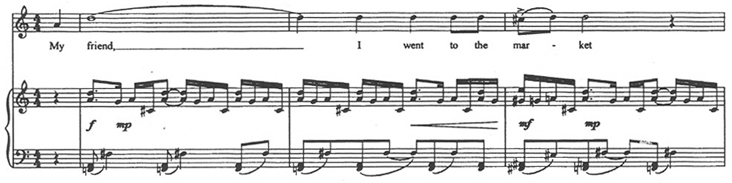

Harbison highlights the text's comparisons between popular opinions and Mira's opinions of her "purchase" by reversing the order in which similar segments of an interval cycle are given. As shown in example 1, pitch collections organized with 3-1-3 intervallic content sound at the end of each comparison in the text.

Example 1: "It's True, I Went to the Market," mm. 7-10 and 17-20, organized with 3-1-3 intervallic content.

The four pitch collections are summarized in a linear fashion in example 1, illustrating how they may be combined and arranged to create a 3-1-3 interval cycle, with some segments held in common among the four collections. The conclusion of the second negative line, "You say I gave too much," is balanced by the positive response of the first comparison, "I claim by day," each containing a triad with a split (or combined) major and minor third, and thus two instances of trichord (014). The conclusion of the first negative line, "You claim by night," (m. 8) is analogous to the positive response in a subsequent comparison, "I say [I gave] too little" (m. 20), with the pitch collections occurring on the words "night" and "little" each containing five occurrences of the subset (014). The passages in example 1 are also shaped by traditional voice-leading. For example, the B minor harmony sounding on the downbeats of measures 17 and 19 is alternated with the intervening  minor harmony (downbeat of m. 18), followed by contrary, chromatic motion in the underlying voice-leading as the left hand of the accompaniment shifts from D and

minor harmony (downbeat of m. 18), followed by contrary, chromatic motion in the underlying voice-leading as the left hand of the accompaniment shifts from D and  to

to  and G at measure 20, while the vocal line descends from B to

and G at measure 20, while the vocal line descends from B to  . In the first half of measures 17 and 19, the B triads contain a split third, like the intervening triad on

. In the first half of measures 17 and 19, the B triads contain a split third, like the intervening triad on  (m. 18) labeled on example 1.

(m. 18) labeled on example 1.

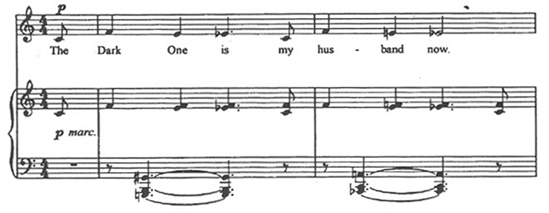

Example 2a illustrates how the song is characterized at times by an overt usage of elements of tonality, such as the opening passage that is organized around the pitch center D with the vocal line's traditional melodic gesture and the split third harmony on D that creates set-class (014): D, F, and  .

.

Example 2: Excerpts from "It's True, I Went to the Market."

a. mm. 1-3

b. mm. 27-29

c. mm. 43-44

d. 3-1 Intervallic relationship among pitch centers

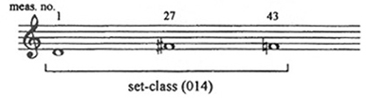

This set-class also occurs at the largest level of the song's organization, with each of these members of the opening harmony acting as a pitch center (example 2). There is no closure on D at the song's conclusion, as the ostinato figure associated with F recurs just prior to the last three harmonies, and the pitch-class  is emphasized as much as D. The song's tonal elements coexist with the intervallic organization, such as the 3-1-3 cycle described above. Some of the resulting harmonies may be considered as extended tertian harmonies, or as tertian harmonies with "split" members or added pitches, but the intervallic perspective applies as well, and so the use of various analytical tools may offer the best approach in the classroom. Because the song is characterized by a combination of familiar tonal elements and clear, recurrent intervallic patterns, it may provide a transitional link among tonal and post-tonal works studied in an undergraduate theory class, while also enabling a simple, straightforward introduction to some of the tools of set theory.

is emphasized as much as D. The song's tonal elements coexist with the intervallic organization, such as the 3-1-3 cycle described above. Some of the resulting harmonies may be considered as extended tertian harmonies, or as tertian harmonies with "split" members or added pitches, but the intervallic perspective applies as well, and so the use of various analytical tools may offer the best approach in the classroom. Because the song is characterized by a combination of familiar tonal elements and clear, recurrent intervallic patterns, it may provide a transitional link among tonal and post-tonal works studied in an undergraduate theory class, while also enabling a simple, straightforward introduction to some of the tools of set theory.

This song, like the others in Harbison's set, concludes with a typical Indian device, a signature line that identifies the poet:

Mira says: The Dark One is my husband now

Be with me when I lie down;

You promised me this in an earlier life.

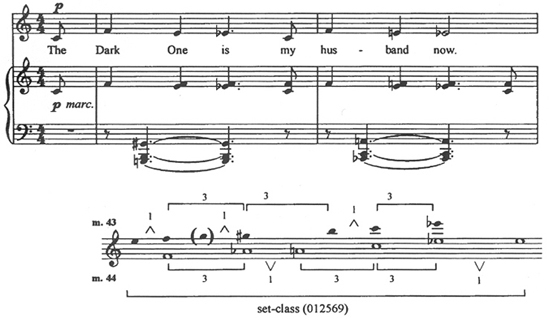

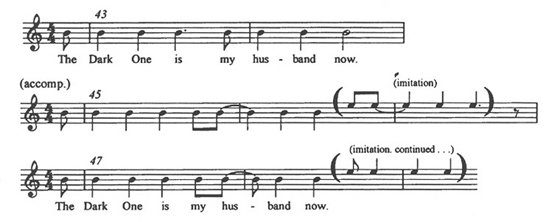

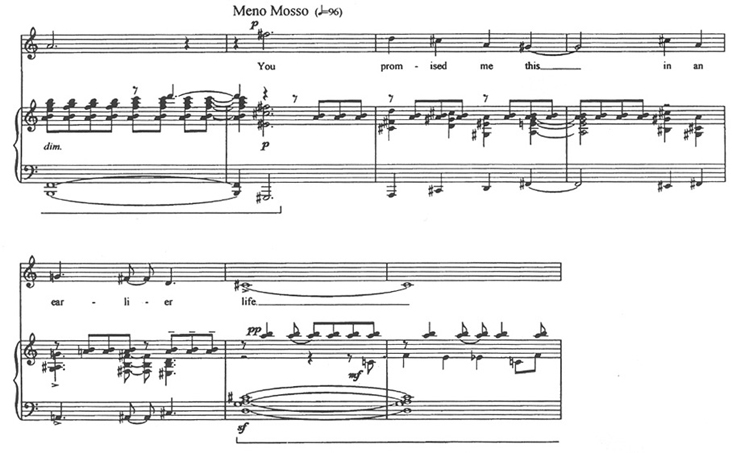

This plea for Krishna's presence is an example of a mantra that Mira would have chanted repeatedly, and Harbison's setting exudes the trance-like atmosphere created in this deep state of worship, with the combination of hexachords based on set-class (014) and the use of two ostinato figures. In the first ostinato (mm. 43-44), hexachord (012569), which contains the 3-1-3 intervallic pattern and is thus saturated with subset (014), sounds in each measure, setting the text "The Dark One is my husband now" (example 3a).

Example 3: "It's True, I Went to the Market."

a. "Husband" ostinato (mm. 43-44), organization with 3-1 intervallic pattern

b. Rhythmic evolution of "husband" ostinato (version for chamber ensemble)

c. Imitative treatment of "Be with me" ostinato (version for chamber ensemble)

In measure 43, this hexachord excludes  , but this pitch-class represents interval-class 1 in its relationship to

, but this pitch-class represents interval-class 1 in its relationship to  and belongs to an occurrence of subset (014), so it is related to the cycle as labeled on example 3a. This intervallic consistency, together with the gradual evolution of the ostinato's rhythmic motives, creates a hypnotic effect (see example 3b). The second ostinato is identified by its rhythmic organization, as it consists of the repetition of a single pitch with the text "Be with me when I lie down." The imitative and fragmentary uses of this rhythmic ostinato are shown on example 3c.

and belongs to an occurrence of subset (014), so it is related to the cycle as labeled on example 3a. This intervallic consistency, together with the gradual evolution of the ostinato's rhythmic motives, creates a hypnotic effect (see example 3b). The second ostinato is identified by its rhythmic organization, as it consists of the repetition of a single pitch with the text "Be with me when I lie down." The imitative and fragmentary uses of this rhythmic ostinato are shown on example 3c.

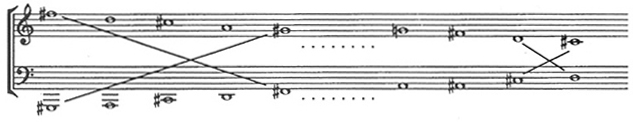

These ostinato figures are layered and woven into the texture until the end of the song, expressing a sense of eternally repeating life cycles referenced in the final line of text. This reference to cycles of rebirth so characteristic of Hindu beliefs is also expressed through other musical means, as seen in example 4: a symmetrical soprano and bass voice-exchange is created by the retrograde relationship between these voices (mm. 56-58), set-class (015) is used in a circular manner in both voices, the outer voices converge on the exchanged pitch-classes D and  at the downbeat of measure 60, and the two ostinato patterns illustrated above are used continually until the final cadence.

at the downbeat of measure 60, and the two ostinato patterns illustrated above are used continually until the final cadence.

Example 4: "It's True, I Went to the Market."

a. mm. 55-61

b. Soprano and bass voice exchanges, mm. 56-60

c. Circular convergence of (015) trichords, mm. 56-60

The second poem set by Harbison is quoted below.

"All I Was Doing Was Breathing"

Something has reached out and taken in the beams of my eyes.

There is a longing, it is for his body, for every hair of that dark body.

All I was doing was being, and the Dancing Energy came by my house.

His face looks curiously like the moon, I saw it from the side, smiling.

My family says: "Don't ever see him again!" And imply things in a low voice.

But my eyes have their own life: they laugh at rules, and know whose they are.

I believe I can bear on my shoulders whatever you want to say of me.

Mira says: Without the energy that moves mountains, how am I to live?

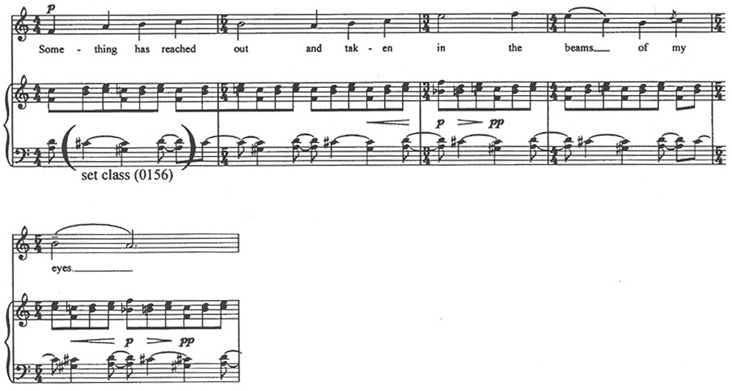

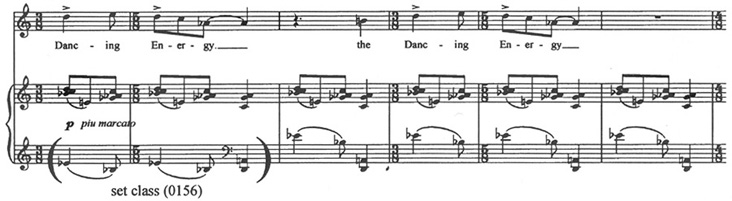

This song draws much of its pitch content from set-class (0156), which is often disposed in the accompaniment as the combination of two perfect fourths separated by a half-step (example 5).

Example 5: "All I Was Doing Was Breathing," mm. 5-9.

The song opens with this set-class given explicitly in the ostinato figure of the piano part (left hand), while the vocal line has a lydian modal organization and emphasizes (0156), as well. The opening vocal line stresses pitch-classes B and C through their frequent use and pitch-classes E and F through their placement as the first (F, m. 5) and highest (E and F, mm. 7-8) pitch-classes. Together, these pitch-classes (B, C, E, F) form another occurrence of (0156), which is reinforced by the content of the piano's right-hand ostinato (mm. 5-6, for example). Much of the song's accompaniment is derived from the same set-class in a manner that maximizes variety in pitch-class content. In measures 1-28, nearly every one of the twelve possible transpositions of the set occurs in the left hand ostinato except for T1 of its original statement, or pitch-classes A- -D-

-D- . Harbison reserves this transpositional level for setting the important text, "Dancing Energy," a reference to Krishna, and he combines it with whole-tone material in the vocal line and right hand of the piano accompaniment (example 6).

. Harbison reserves this transpositional level for setting the important text, "Dancing Energy," a reference to Krishna, and he combines it with whole-tone material in the vocal line and right hand of the piano accompaniment (example 6).

Example 6: "All I Was Doing Was Breathing," mm. 29-34.

The alternating groupings of three and two eighth notes beginning in measure 30 also emphasize this passage by contrasting strongly with the static effect created by constant repetitions of the same rhythmic ostinato pattern before this point. This passage underlines the general notion of dance as a form of worship. In discussing these songs, Harbison has emphasized the fact that these poems were originally sung and danced events, with the melodies being secondary in importance. According to him, the text and dance are the primary factors in the songs of Mirabai.19

The song's opening line, "Something has reached out and taken in the beams of my eyes," and a subsequent line, "My eyes have their own life, and they know whose they are," are references to darsan, or sight. As Martin-Kershaw explains, "sight, to see and be seen, stands as a central metaphor" in this tradition. Metaphors relating to sight and to a separate life occurring within one's eyes are found frequently in Mira's poems; some additional examples are given below.20

Live in my eyes for a little while my amorous Krishna,

admiring Krishna dwell in Mira's heart.

(regarding separation from Krishna:)

My two eyes will not listen to what I say;

Overflowing like rivers in the rainy season.

My eyes don't blink without your darsan.

You are my life breath lover, how can I live?

My heart is not diverted for a moment without your darsan. . . .

My eyes are lost in weeping, my life lost . . .

Sweeping down the path and gazing down the road,

Mira says, Lord when will we meet? Meeting you I find such joy.

from a modern version of "It's True, I Went to the Market"

(as sung by Indira Devi)I keep my lover in my eyes now, behind the screen of my lids.

The enemy world cannot snatch Him away in an instant;

time cannot steal Him.

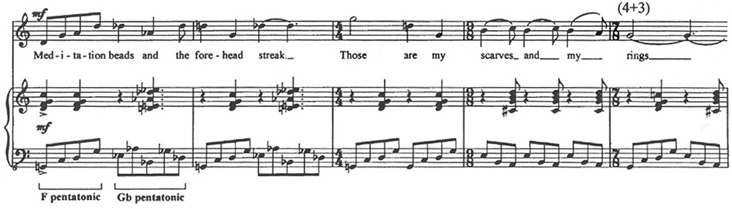

The third song, "Why Mira Can't Go Back to her Old House," offers a stark contrast between worldly values and the life Mira seeks as one devoted to Krishna. The song's opening lines contrast these two views with metaphors describing how Mira's "feminine wiles" are not jewelry and scarves, but symbols and actions pertaining to her relationship with Krishna (example 7).

Example 7: "Why Mira Can't Go Back to Her Old House," mm. 15-19.

These lines of text are supported with alternations between different pentatonic collections, often times those sharing no common tones. Pitch collections containing F and  pentatonic scales are alternated (mm. 15-17), stressing contrast in pitch content, just as the poem draws its emphatic distinctions. Changes in meter, and especially the repeated groupings of three eighth notes occurring on the words "scarves and my" also emphasize the contrast being drawn in the text.

pentatonic scales are alternated (mm. 15-17), stressing contrast in pitch content, just as the poem draws its emphatic distinctions. Changes in meter, and especially the repeated groupings of three eighth notes occurring on the words "scarves and my" also emphasize the contrast being drawn in the text.

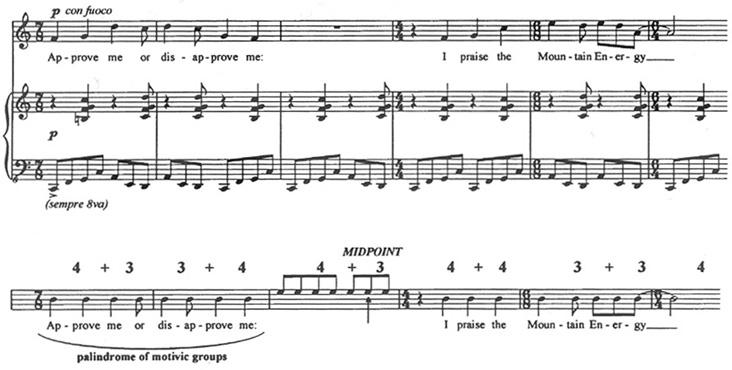

This song is the most interesting of the set in terms of rhythm and meter: additive processes create irregularity in metric patterns, patterns of phrase rhythm are altered in ways that emphasize aspects of the poem, and rhythmic grouping patterns support the meaning of the text. In measure 30 and following, the defiant statement, "Approve me or disapprove me, I praise the Mountain Energy," is set with a symmetrical pattern (example 8).

Example 8: "Why Mira Can't Go Back to Her Old House," mm. 30-35.

At the level of rhythmic motives, the text "Approve me or disapprove me" is set in palindromic fashion. At a larger level, the durations of rhythmic groupings within measures 30-35 combine to create a symmetrical setting for the two lines of text, the midpoint of which occurs in measure 32. Harbison's musical use of symmetry underlines the fact that Mira's devotion is constant, regardless of public opinion.

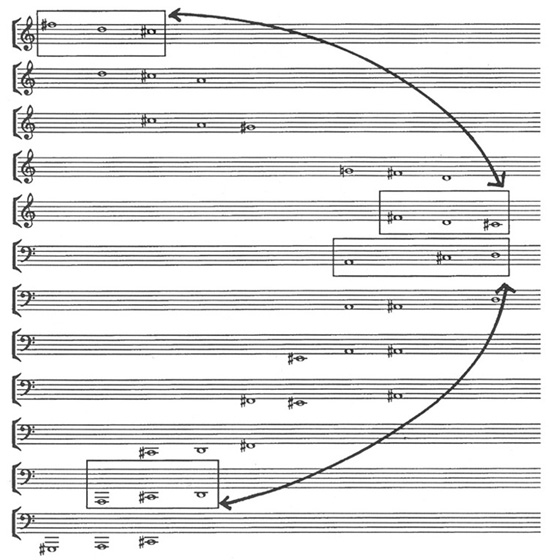

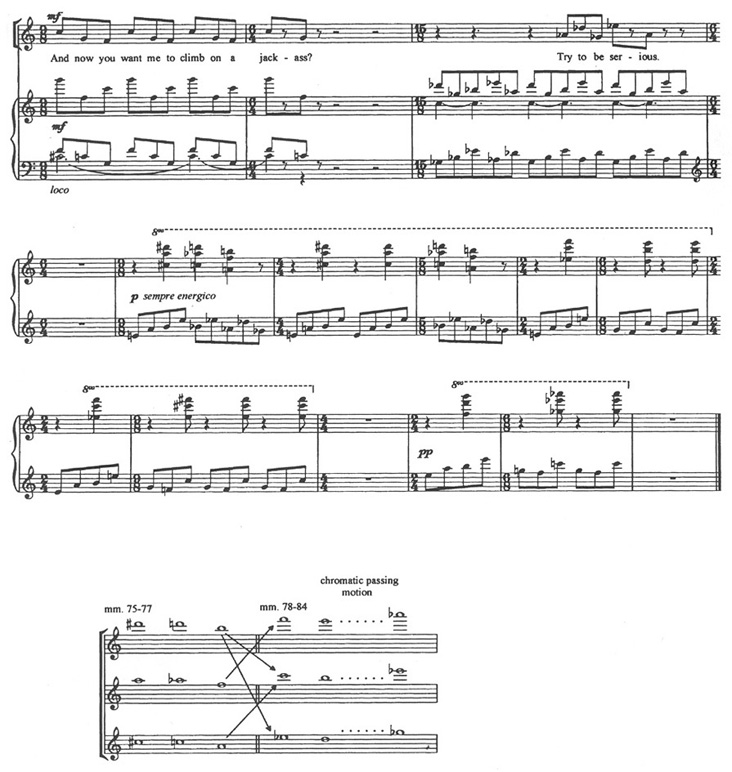

Several passages of the song employ rotations of motives. In measures 71-72, a trichordal subset of the pentatonic scale is sung and played in each possible rotation simultaneously (example 9).

Example 9: "Why Mira Can't Go Back to Her Old House," mm. 71-85.

A similar treatment of the full pentatonic scale on  occurs in measure 73. Further, the instrumental postlude is organized in such a manner that the melodic trichords of measures 75-77, each of which belongs to set-class (014), combine symmetrically with an adjacent voice part in measures 78-84. The pairings of melodic trichords related by inversion contain two invariant pitch-classes (only the pairing of the lowest voice with the inner voice contains one common tone [C]). Each pair of trichords is labeled with an arrow on example 9.

occurs in measure 73. Further, the instrumental postlude is organized in such a manner that the melodic trichords of measures 75-77, each of which belongs to set-class (014), combine symmetrically with an adjacent voice part in measures 78-84. The pairings of melodic trichords related by inversion contain two invariant pitch-classes (only the pairing of the lowest voice with the inner voice contains one common tone [C]). Each pair of trichords is labeled with an arrow on example 9.

The concluding text of this song is perhaps the most sarcastic in Mira's comparison between a relationship with Krishna and that with an earthly husband: "I have felt the swaying of the elephant's shoulders; and now you want me to climb on a jackass? Try to be serious." The chromatic motion and melismatic setting of the words "swaying" and "shoulders" associated with an elephant are strongly contrasted with the syllabic, pentatonic phrase associated with the donkey. Ironically, these lines of text were used to criticize Mira during her own lifetime. When a member of a religious sect visited her and others devoted to Krishna, another member of his sect sent a letter to the man, chiding him for leaving them and their male guru in order to spend time studying and worshipping with Mira—accusing the man of "exchanging an elephant for a jackass." Upon receipt of the letter, the man left immediately, returning to his guru. This story highlights the fact that although Mira was respected by many sects, she was officially related to none.21

Another version of this poem differs from the one set by Harbison through its inclusion of additional lines (compare the two versions given below, the first of which was translated by Bly and set by Harbison).

"Why Mira Can't Go Back to Her Old House"

The colors of the Dark One have penetrated Mira's body; all the other colors washed out.

Making love with the Dark One and eating little, those are my pearls and my carnelians.

Meditation beads and the forehead streak, those are my scarves and my rings.

That's enough feminine wiles for me. My teacher taught me this.

Approve me or disapprove me: I praise the Mountain Energy night and day.

I take the path that ecstatic human beings have taken for centuries.

I don't steal money. I don't hit anyone. What will you charge me with?

I have felt the swaying of the elephant's shoulders; and now you want me to climb on a jackass?

Try to be serious.

Mira is dyed in Hari's color, blocking out every other hue.22

I will sing for the Mountain Bearer, I will not be a sati.

My mind is charmed by the one named for the clouds.

Ranaji, our relationship is no longer brother-in-law, sister-in-law,

You are servant and I master.

Give me [only] bangles, tilak and rosary to wear, the vow of chastity is my ornament.

Other ornaments do not please me, Ranaji; this guru's knowledge is mine.

Some condemn me, some praise me—I will sing of the attributes of Govind.23

The path which the saints travel, that road I will take.

I neither steal nor hurt any creature, what can anyone do to me?

The one who has mounted an elephant will not climb up on an ass!

Such a thing cannot be.

Those who rule are hell dwellers; pleasure seekers are taken by the God of Death.

Those who engage in devotion win release; those who do yoga live.

The Mountain Bearer is my husband and my family;

The Mountain Bearer my mother, father, son, brother.

Rana, you are without depth [and] I am weary of this place, says Mirabai.

The most notable addition in the second version is the second line, "I will sing for the Mountain Bearer; I will not be a sati." Here Mira overtly refuses to follow the pressures of society to end her own life because of the death of her husband. This significant difference between the two versions of Mira's poem raises the issue of the "remaking" of Mira, or reshaping of her story as one of an obedient wife who turned to bhakti only after her husband's death. Nineteenth- and early twentieth-century accounts of her story, in particular, often omit references to her socially unacceptable behavior. As British political and cultural dominance over India became more pervasive in the late nineteenth century, a nationalist Indian response included an effort to reshape the Hindu identity, and even an attempt to "remake" Krishna as a non-pagan god "who would not humiliate his devotees in front of the progressive Westerners" by dismissing ancient descriptions of him that did not fit the current standards for political, social, and sexual norms.24 Mirabai may have been subjected to the same type of transformation—being "made over" into an ideal wife and model woman by those who simply refuted or ignored any of her traits or actions that did not fit the politically correct ideal.25

As a saint, Mira's wide popularity spans across the centuries and across India, extending to people of both Muslim and Hindu faiths. In recent years, her story has been told in several films. She is even the subject of a series of comic books, in which she emerges as a heroine after encountering various challenges; however, she is still portrayed as obedient to her husband and the other men around her.26 As a religious figure, Mira is nearly always praised; as a woman, however, she is regarded with ambivalence, even today. For an Indian woman to be referred to as "Mira" today is often considered a term of abuse—as a reference to a woman who does not accept what her family says, or cannot be controlled. If used as a term for a young woman who dances, sings or writes poetry, or as a name for a widow who begins a life of religious commitment after her husband's death, the name is used as a compliment.27 The name "Mira" is often used to refer to a woman "who resists social definitions of women's roles and behavior . . . who meets men as an equal in religious or other intellectual discourse; who renounces a life of privilege for a higher cause . . ." Her story functions ultimately as "an assertion of a woman's individual and spiritual potential that resonates across the hierarchy of caste and by implication as a demand for recognition of the dignity and humanity of anyone who suffers at the hands of a 'rana' [ruler] of any kind."28

In summary, the Mirabai Songs may serve as a vehicle for broad, interdisciplinary investigations in an undergraduate theory class. Freshman and sophomore students generally find the songs accessible and compelling, and the texts arouse their curiosity. Musically, the songs offer opportunities to explore topics frequently discussed in a sophomore theory class. Because the songs encompass elements of tonality but also other types of pitch organization based on intervallic cycles or pitch collections such as whole-tone and pentatonic scales and modes, they may serve as a good source for discussions on a broad range of topics associated with pitch organization, including tonality and centricity, and an introduction to the tools of set theory. Study of the rhythmic and metric aspects of the text and its setting could also be supplemented with an ethnomusicological perspective of rhythm, meter, and dance in Indian music—especially since Mira's songs are still being sung and recorded there today.

Mirabai's poems are fascinating, even apart from their musical settings. Their use of religious metaphors and aspects of traditional folk and classical poetry offers windows into Hindu beliefs and Indian culture. For example, the myths surrounding Krishna as the Mountain Bearer and most importantly, as a divine lover, are frequently incorporated within her poems. In some cases, such as the poem that was set in the first of Harbison's songs, "It's True, I Went to the Market," Mira even refers to herself as being Radha (who is described in the myths as Krishna's favorite wife) in a former life. The reshaping of Mira's story throughout the centuries enables an historical perspective of India, especially in its response to Western colonialism in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Comparisons of different versions of her biography and of her poetry, such as the two versions of "Why Mira Can't Go Back to her Old House" given above, provide a view of the different time periods and cultural contexts in which a poem was recorded and also the varied religious and political value systems of those who recorded it. Mirabai's poetry also offers a feminist perspective through its criticisms of the caste system and of the exclusion of women from full participation in religious customs. Any thoughtful study of her life and poetry requires reflection on women's issues in Indian culture past and present, including the practice of sati and reactions to its recent occurrence (1987) described above. The Mirabai Songs invite careful consideration of a number of interesting musical, cultural, and even ethical issues, and call for an awareness of a culture other than our own. Developing this breadth of perspective and applying critical thought to these issues would seem to be worthy goals for an undergraduate experience.

1An earlier version of this article was presented as part of a CMS paper session at the joint Musical Intersections conference in Toronto, in November, 2000.

2Claire Olanda Vangelisti, "John Harbison's Mirabai Songs: A Poetic and Musical Analysis" (D.M.A. treatise, University of Texas at Austin, 1997), 78. Permission to reprint musical excerpts from Mirabai Songs granted by G. Schirmer, Inc., and Associated Music Publishers, Inc. Copyright © 1983 by Associated Music Publishers, Inc. International Copyright Secured. All Rights Reserved. Reprinted by Permission.

3Nancy Martin-Kershaw, "Mirabai in the Academy and the Politics of Identity," in Faces of the Feminine in Ancient, Medieval, and Modern India, ed. Mandakranta Bose (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000), 166.

4The many versions of Mirabai's story, including both a survey of pertinent historical records and an overview of oral traditions (based in part on recent field work in India) are summarized in Nancy Martin-Kershaw, "Dyed in the Color of her Lord: Multiple Representations in the Mirabai Tradition" (Ph.D. diss., Graduate Theological Union, 1995).

5This idol represents Krishna lifting a mountain, which is a reference to a myth in which he protects his followers from the storms created by an angry rain god by lifting a mountain above them like an umbrella, and sheltering them in this way for several days. Mira's poems often refer to Krishna as the "Mountain Bearer." See Vangelisti, 93-4.

6For a discussion of the continued practice of arranged marriages and ways in which the custom has been modified in recent years, see Elisabeth Bumiller, May You Be the Mother of a Hundred Sons: A Journey among the Women of India (New York: Ballantine, 1990), 24-43.

7Martin-Kershaw, "Dyed in the Color," 63.

8Ibid., 53. As early as the fourth century, B.C.E., examples of sati can be found in northwestern India, but the tradition of validating the practice did not begin until around the eighth century. The actual practice of sati was not widespread. See Mandakranta Bose, "Sati: the Event and the Ideology," in Faces of the Feminine, 21-32.

The practice of sati has been illegal since 1829; however, as recently as 1987 an eighteen-year-old Rajput woman, Roop Kanwar, was immolated on the funeral pyre of her husband. Thousands witnessed her death, and crowds of several thousand people responded to the event with both celebrations and protests in the following weeks. The meaning of her death and its polarizing effect on the Indian population is still widely debated. See Veena Talwar Oldenburg, "The Roop Kanwar Case: Feminist Responses," in Sati, the Blessing and the Curse: The Burning of Wives in India, ed. John Stratton Hawley (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), 101-30.

9As Bose notes, previous debates have focused on the interpretation of religious law and whether historical precedents serve as validation for the act of sati. She suggests that a more appropriate question is how the practice should be viewed—whether it is voluntary or coerced. Bose raises the question of whether a woman who cannot choose her mate or make other major decisions about her own life can really decide anything for herself. "Indoctrination is as coercive as brute force, which is why we have to look at the nature of the ideology that hangs over the heads of Indian women and, for that matter, women everywhere else." Bose, "Sati," 29.

10These accounts are not necessarily directly related to those of her husband's death. The murder plots are described as a response to Mira's insistence on worshipping Krishna and her socially unacceptable practice of conversing with holy men outside the family. Martin-Kershaw, "Mirabai and the Academy," 163.

11Vangelisti, 52-3, and Martin-Kershaw, "Dyed in the Color," 2-3.

12Vangelisti, 53-4.

13Martin-Kershaw, "Dyed in the Color," 6.

14J.L. Brockington, The Sacred Thread: Hinduism in its Continuity and Diversity (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1981), 130; Vangelisti, 57-8; and Martin-Kershaw, "Dyed in the Color," 7.

15Martin-Kershaw, "Dyed in the Color," 399.

16Vangelisti, 61.

17Ibid., 220.

18The translations of Mira's poems that were set by John Harbison are located in Robert Bly's Mirabai Versions (New York: Red Ozier Press, 1984) and reprinted in Vangelisti. The composer incorporated only a few minor textual changes in his musical settings. Unless specified otherwise, all translations of the poems set by Harbison and cited here are drawn from this source. In an interview with Claire Vangelisti (recorded in her dissertation), Harbison mentions his knowledge of Bly's translations of Mirabai's poems through an earlier collection of Bly's, which also included her poems; see Bly, News of the Universe: Poems of Twofold Consciousness (San Francisco: Sierra Club, 1980).

19Vangelisti, 218.

20Martin-Kershaw, "Dyed in the Color," 181; translations of these excerpts are by Martin-Kershaw and are drawn from the same source, pages 270, 269, 276, and 359-60, respectively. The last excerpt is drawn from Indira Devi's twentieth-century version of the poem set by Harbison as the first of the Mirabai Songs ("It's True, I Went to the Market"); the translation is based on Indira Devi, "Govind Lino Mol," in Shrutanjali (Pondicherry: Sri Aurobindo Ashram, 1951), 94.

21Martin-Kershaw, "Dyed in the Color," 75.

22Ibid., 80. The translation is by Martin-Kershaw. In the third line, Mira is referring to Krishna, who is sometimes called Dhana Shyam, the "Dark Cloud," due to both his dark complexion and the clouds that signify the rainy season, which is also considered to be the season of love. The fifth of the six Mirabai Songs, "The Clouds," is based on another poem that incorporates the same metaphors. Ranaji, or rana (line 4), is a term for the ruler of Mewar. Some versions of Mira's story claim that her brother-in-law filled this role after her father-in-law and husband were killed in a war.

23Govind is another name for Krishna.

24Ashis Nandy, The Intimate Enemy: Loss and Recovery of Self Under Colonialism (Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1983), 24.

25Martin-Kershaw, "Mirabai in the Academy," 167.

26Vangelisti, 45.

27Martin-Kershaw, "Dyed in the Color," 414-18.

28Ibid., 468-69 and 484.