It has been almost fifty years since Louis Armstrong's Hot Five and Hot Seven recordings of 1925-19281 were first recognized in print as a watershed of jazz history and the means by which the trumpeter emerged as the style's first transcendent figure.2 Since then these views have only intensified. The Hot Fives and Hot Sevens have come to be regarded as harbingers of all jazz since, with Armstrong's status as the “single most creative and innovative force in jazz history” and an “American genius” now well beyond dispute.3 This study does not question these claims but seeks, rather, to determine the hitherto uninvestigated origin of such a seminal event and to suggest that Armstrong's genius was present from the beginning of the project.

Illustration 1: Louis Armstrong and His Hot Five

I. Historical Background

The seeds of the idea that germinated into the Hot Five and Hot Seven may have been sown in the early morning hours of June 8, 1923 at the Convention of Applied Music Trades in Chicago's Drake Hotel. On that date King Oliver's Creole Jazz Band, one of several groups hired to entertain the conventioneers at a “midnight frolic,” was scheduled at three a.m. For a twenty-minute set, which, by repeated calls for encores from the band's “mob of admirers,” grew to almost two hours. But typical of the racial climate of the time, twenty-one-year old Louis Armstrong, in his first known mention by the white press, impressed the reporter more by his appearance than by his playing: “The 'dark horse' orchestra of the whole bunch was sure dark. Especially the little frog-mouthed boy who played the cornet.”4

Two weeks later Oliver recorded for Okeh Records, and, in the Windy City's annual Elks Parade the following month, his band rolled through town on a flatbed truck advertising the special release of “Dippermouth Blues” and “Where Did You Stay Last Night?” Posters of Okeh race artists were prominently displayed along the line of march, with the placarding of the colored district personally supervised by E. A. Fearn, “who spared no expense in this work.”5 Thus are introduced in the Hot Five/Hot Seven story two names indissolubly linked—OKeh and Elmer [E. A.] Fearn—without which the recordings would never have been made.

Okeh was formed in 1918 by Otto Heineman, president of the prosperous Heineman Phonograph Supply Company (later reorganized into The General Phonograph Corporation), to complement and expand his business of manufacturing high-quality phonograph motors, needles, and parts. Ostensibly derived from the “original spelling of the initials—OkeH.6 The company's accidental creation of the race record market—i.e., black music for black audiences—with the serendipitous success of Mamie Smith's “Crazy Blues” in 1920 need not be recounted here,7 other than noting that by the time Armstrong formally joined Okeh in late 1925, the firm was the race market leader with dozens of black artists signed to exclusive contracts.

A technological leader of the industry as well, Okeh set standards for recording quality under the supervision of C. L. Hibbard, recognized as “one of the foremost recording engineers in the country” and the inventor of a number of new recording methods and devices, including the first portable recording studio. In 1925 Hibbard perfected the “Truetone” process which enhanced the tone quality of sound recordings. Success of the process and Hibbard's technical ingenuity may explain the company's somewhat delayed transition from acoustic to electronic [microphone] recording in 1927.8

E. A. Fearn, a native of Chicago, formed Consolidated Talking Machine Company from five smaller firms with himself at age thirty as president in 1918, and undertook the business of phonograph sale and repair and of record distribution from his downtown store at 227 W. Lake Street. Displaying early on a flair for promotion that was to distinguish his career, Fearn became the sponsor of an “Okeh Record Football Team” with a mammoth Okeh disk as its official team mascot. Five years after its founding Fearn's enterprise moved from West Lake into a four-story building at 227-229 W. Washington, added branches in Detroit and Minneapolis, and boasted a local sales force of fourteen, plus several “road men.” Consolidated Talking Machine had by now grown to be “one of the most successful Okeh jobbers in the country” and its president generally regarded “as one of the best-posted wholesale men in the country,” whose observations about the industry were frequently sought by the head of Okeh's parent firm, Mr. Heineman himself.9

The King Oliver recordings of June 22-23, 1923 were the first to be made by Okeh in Chicago. Although the notice in Talking Machine World failed to specify the location of the temporary recording laboratory for the first Oliver dates, it was almost certainly situated in the fourth floor stockroom of Consolidated Talking Machine where Oliver recorded his second Okeh session the following October. Consolidated hosted Okeh's next visit to the Windy City in early February 1924 while temporarily housed at 216 N. Michigan because of a fire that damaged the top two floors of its headquarters the previous December. By mid-1924, Fearn's company, long back into its remodeled facilities, was the sole OKeh jobber with its president celebrated by company executives in New York for his splendid achievements in the development of the label's business. A year later an “elaborate and scientifically constructed recording laboratory” was permanently installed on the fourth floor of Consolidated's facilities, thereby eliminating the necessity for transporting recording equipment from New York as in the past.10

Meanwhile Armstrong had fallen in love with the Creole Band's pianist, Lil Hardin. After obtaining divorces from their respective mates—Daisy, still in New Orleans, and singer, Jimmy Johnson—the couple married in early February 1924 and spent their honeymoon with the Oliver band playing one-nighters on an “extended tour on big time” throughout the Midwest.11 Upon their return to Chicago in June, Lil talked her husband into leaving Oliver, with whom he was playing second cornet, to seek a more suitable showcase for his burgeoning talent. After being rejected by society band-leader, Sammy Stewart, Armstrong played briefly with Ollie Powers before accepting an offer in September 1924 from Fletcher Henderson in New York City. A year later Lil summoned her husband back home to join her band at the Dreamland, the premier cabaret on The Stroll or center of black nightlife in South Chicago. Armstrong, having vomited on his leader's “nice clean tuxedo shirt” from overzealous partying on his last night in New York, arrived in Chicago in early November to begin living up to his advertised reputation as the “World's Greatest Jazz Cornetist.”12 Within days of his return the Hot Five sessions began, and three years later, jazz, by universal consent, was forever transformed.

II: The Hot Five

Who deserves credit for the Hot Five idea? Lil speculated that the Okeh representative responsible for the Hot Five sessions was Tommy [T.G.] Rockwell, who came to Chicago from the West Coast around the time of the first Hot Five recordings. But Rockwell's new position as manager of the recording department for Columbia's local branch would seem to preclude his hiring of Armstrong for a rival company. Later, however, after moving to Okeh as director of recording (despite a reputed “tin ear”) in the spring of 1927, as an Okeh executive in New York in 1929, and as Armstrong's first manager from 1929-1931, Rockwell, indeed, exerted considerable influence on the trumpeter's career.13

Of Chicago saxophonist Bud Jacobson's claim to have persuaded E. A. Fearn to record an all-star quintet under Armstrong's direction, very little can be ascertained. While primarily a retailer and promoter, Fearn could sign up Okeh artists (while not having the authority to release their recordings), but his being significantly influenced by Jacobson, then nineteen and one of the white Chicagoans hanging out with members of the Austin Hill Gang, seems implausible. Jacobson and his bunch, however, haunted the Dreamland when Armstrong was there, and he and a friend were “the only whites” at the Okeh Cabaret and Style Show, which featured an appearance by the Hot Five in June, 1926.14

Johnny St. Cyr, the guitar-banjoist15 of the original Hot Five, thought Fearn hired Armstrong directly: “Having recorded on numerous occasions with King Oliver for the Okeh label, Louis became well known to Mr. Fern [sic] who was the recording engineer [sic] for that company at the time. . . .Mr. Fern insisted that Louis record only his own compositions, and persuaded him to sign a five year contract, which Lil and I had advised Louis not to do.”16 Armstrong in a 1951 interview implied something similar: “The minute Mr. Fern (the President [sic] of the Okeh Company) gave me the go sign, I hit the phone and called the Musician's Union, and asked permission to hire Edward “Kid” Ory (trombone), Johnny St. Cyr [guitar-banjo], and Johnny Dodds [clarinet].”17 Ory, on the other hand, credited Richard “Myknee” Jones, Okeh's Race Division manager in Chicago since mid-1923,18 to have arranged the Hot Five dates. Since Jones could not have negotiated with Okeh on his own, Fearn, his supervisor, presumably hired the personnel, perhaps with additional pressure from Lil, a good friend of Jones.19

But regardless of speculations about a Chicago contract, Armstrong's initial agreement with Okeh had to have been made in New York. Ory, in California, remembered receiving a letter from Louis in New York saying that he had offers to play in the Dreamland and to record for Okeh. The money Armstrong mentioned sounded attractive so Ory broke up his band and hurried to the Windy City, arriving “a few weeks” before Louis.20 Okeh in New York also wired Richard Jones to prepare Armstrong to record with Bertha “Chippie” Hill in Chicago, which the cornetist did on November 9.21

The critical link between Armstrong and Okeh appears to have been Ralph Peer, Okeh's Director of Production and, after December 1925, the company's General Sales Manager. Peer entered the record business as a teenager by working for his father, a Columbia dealer in Independence, Missouri, eventually landing a position with the Columbia organization in Kansas City. After brief service in the Navy towards the end of WWI, Peer returned to his old job in Kansas City, but shortly thereafter was hired by his former Columbia boss, who had in the meantime joined Okeh in New York. Rising quickly to a position of authority in sales, Peer was the first in the record business to act on the implications of the “Crazy Blues” phenomenon. Claiming to have coined the term, “race record,” Peer began a separate number series and catalog for these recordings, which he was to do later for “hillbilly” music as well. Soon he was scouring the country for race and hillbilly artists with Hibbard and his portable recording studio in tow.22 It was to Peer that Lil Armstrong appealed on her husband's behalf:

I used to go to Chicago frequently [on sales trips] while I was with Okeh. I would go out late at night to the Royal Gardens [where] I got acquainted with Armstrong and his wife [who] came up to me and said “Louis has an offer to go to New York [with Henderson's Orchestra]. Could you give us recording work there?” . . . so we used a pickup orchestra with Louis Armstrong on trumpet . . .Whenever we needed a New York trumpet player our first choice would be Louis Armstrong. So this went on for a year or so and finally [Lil] came to see me again and said, “[Louis] can't stand it in New York.” And I said, “Well, now if he goes back to Chicago, I will do this for you. We will create an Armstrong orchestra so that we can give you some work” . . . [He] went back to Chicago and we sent a recording outfit to an old warehouse there . . . and rented a floor . . . I got the best musician's that you could get . . . because I liked Louis . . . I okeyed the musicians, all of whom I knew . . . I'd really set up the dates around Louis. I really did it to get him enough money so he could pay his way up there . . .that was the beginning of Louis Armstrong.23

The Hot Five recordings were usually made in the morning between the completion of members' regular or doubled gigs and their heading home for a few hours sleep. St. Cyr's regular job with Doc Cooke, for example, lasted from eight until midnight after which he doubled at the Apex Club with Jimmy Noone from one until six a.m. Armstrong, during much of the Hot Five period, started work with Erskine Tate at the Vendome Theater at seven every evening before doubling at the Dreamland or Sunset until three or four in the morning.24 Ory described the routine at the studio:

Our recording sessions would start this way: the Okeh people would call up Louis and say they wanted so many sides. They never told him what numbers they wanted or how they wanted them. Then Louis would give us the date, and sometimes he'd call me and say I'm short of a number for this next session. Do you think you can get one together? . . . We would get to the studio at nine or ten in the morning. . . .If we were going to do a new number, we'd run over it a couple of times before we recorded it. . . . We spoiled very few records, only sometimes when one of us would forget the routine or the frame-up, and didn't come in when he was supposed to.25

The earliest Hot Five recordings were made acoustically, which required the performers to gather around a large horn at varying distances to achieve balance.26 The horn funneled the sounds to a stylus which cut them directly on to a rotating wax disc. Mistakes required starting a new disc. Dodds could not play hot without loudly tapping his right foot, under which Mr. Fearn was obliged to place a pillow to keep from ruining the cuts. The band members were so acclimated to each other's playing that they soon came to rehearse and time the numbers in the studio, thereby eliminating tests and managing to cut a master on the first take.27 Both Ory and St. Cyr remembered the Hot Five sessions as happy, relaxed, and fun, with Louis as a “wonderful” leader who respected his sidemen and put the band before his personal acclaim. Most importantly for posterity's sake, Okeh avoided trying to “expert” the musician's, allowing them almost complete artistic freedom within the studio.28

III. The Music

On November 12, 1925, the first of the Hot Fives were recorded in Okeh's portable studio at the Consolidated Talking Machine Company (Illustration 1 [1926 Okeh publicity shot of Armstrong's Hot Five]).29 Although “no earthshaking jazz” may have resulted,30 the band performed with the confidence and assurance that one might expect from players who had known each other personally and professionally for years. Not surprisingly, the musical style of the first two numbers, “My Heart” and “Yes! I'm in the Barrel,” recalled the players' New Orleans origins and King Oliver's recordings of two years earlier with their ragtime rhythms and ensemble-dominated textures. Although the youngest of the group at twenty-four, Armstrong nevertheless exerted his musical authority by his swinging leads, innovative solos, and hot breaks.

The third cut of the first Hot Five session, “Gut Bucket Blues,” best typified its successors. The number was created at the studio in response to Mr. Fearn's request for a blues to round out the set. When Armstrong complained that all their blues sounded alike, St. Cyr suggested beginning with a banjo solo:

So we made a short rehearsal and cut the number. When Mr. Fern [sic] asked, “What shall we name it?,” Louis thought for a while and then said, “Call it 'The Gut Bucket.'” Louis could not explain the meaning of the name. He said it just came to him. But I will explain it. In the fish markets in New Orleans the fish cleaners keep a large bucket under the table where they clean the fish, and as they do this they rake the guts in this bucket. Thence “The Gut Bucket,” which makes it a low down blues.31

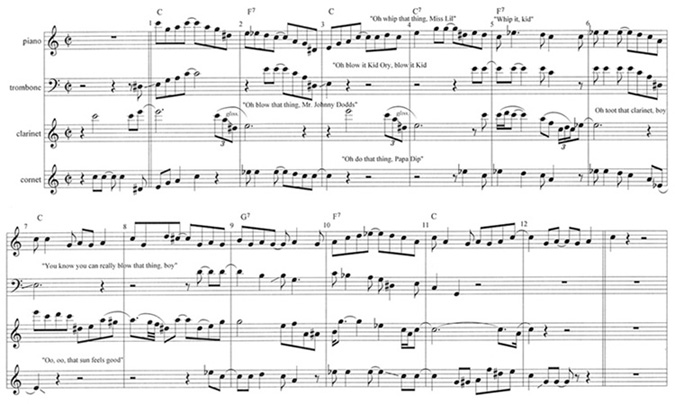

The simple structure of “Gut Bucket Blues” heralds the organization of later Hot Fives—a string of ensemble and solo choruses increasingly showcasing Armstrong. In “Gut Bucket,” however, everyone solos—each urged by the leader to “whip it” or “do that thing.” But when it came time for Dodds to introduce “Papa Dip,” he froze in front of the horn, ruining several takes before finally turning the line over to Ory.32

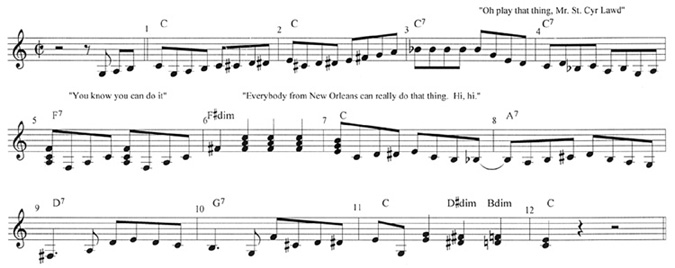

The formal simplicity of “Gut Bucket Blues” belies its sophisticated musical content. St. Cyr's introductory solo, one of his most extensive on record, reveals deft technique and a nicely crafted melodic line spiced with chromaticism rising to a prominent blue seventh (Bb) in bar 3. A passing diminished chord in bar 6, a series of secondary dominants (A7 in bar 8 to D7 in bar 9) before arriving at the dominant (G) in bar 10, constitute a few embellishments of the standard blues progression (Example 1). St. Cyr's progression differs, in fact, from that followed in the rest of the piece: C-F7-C-C7/F7-F7-C-A7/G7-F7-C-C.

Example 1: St. Cyr's Opening solo in “Gut Bucket Blues.”

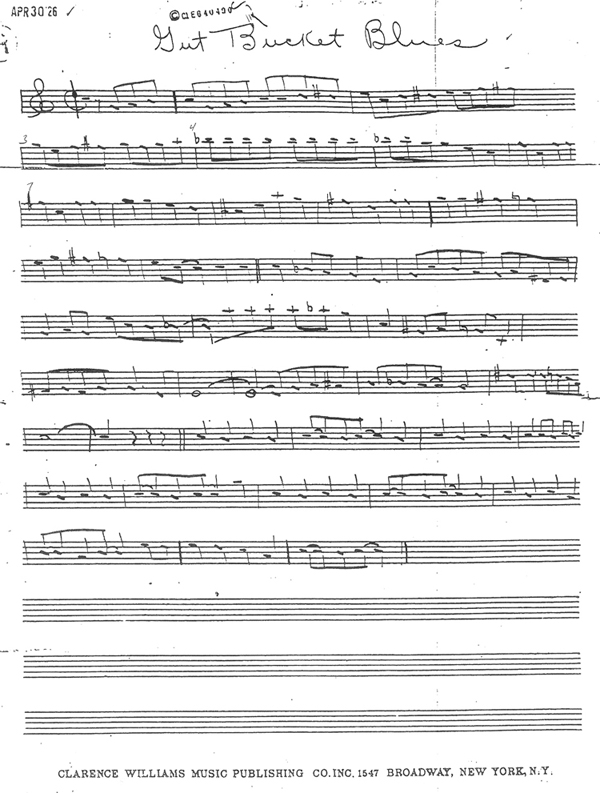

Incidently, the copyright deposit of “Gut Bucket Blues” offers no compositional insights. Submitted several months after the recording, it is a descriptive lead-sheet incorrectly transcribed by Lil from the recording or from memory (Illustration 2 [“Gut Bucket Blues” copyright deposit]).33 The introduction has thirteen bars instead of twelve and bars 1-2 and bars 5-6 of the first ensemble chorus alone resemble Armstrong's recorded cornet lead. The second ensemble chorus, four solo choruses, and Armstrong's solo tag are not included. Only the final ensemble chorus and a few bars of the introduction actually duplicate the recording. Interestingly, Lil's version of St.. Cyr's solo improves the structure of the original by inserting the fifth (G) in its arpeggiation of the C7 harmony, thereby delaying the seventh (Bb) until its expected appearance in bar 4. On the recording, St. Cyr reaches Bb prematurely, making a prolongation of C7 necessary before the move to the subdominant (F) in bar 5. Lil's inclusion of the C7 prolongation from the original (or her interpolation of an arpeggiation on G) produced the introduction's extra bar.

Illustration 2: “Gut Bucket Blues”

On the recording, however, the series of solos after the two ensemble choruses provides a study in motivic development (Example 2).34 Lil introduces a descending five-note motive (C-A-G-D#-E) in bars 1-2, which she repeats twice in bars 2-3, the second time inverted. Blue notes (Ebs) occur frequently as the seventh of the subdominant (F7) but not as the third of the tonic (C) and she refers to the implied A7 from bar 8 of St. Cyr's introduction, a harmonic detail overlooked or ignored by her successors. In sharp contrast, Ory's chorus is less complex and more “primitive.” Avoiding blue notes entirely, he repeats literal statements of Lil's motive, disregarding the Eb/E dissonance with the sounding F7 in bars 2 and 5-6, while Dodds, on the other hand, develops the motive rhythmically in bars 1 and 3 and melodically in bars 7-8. Aside from bar 2, Dodds favors blue notes as sevenths of the subdominant harmonies in 6 and 10.

Example 2: Comparison of Solos from “Gut Bucket Blues”

As the conclusion of the set of solos, Armstrong's performance might be heard as an extension of his colleagues' efforts and a wry reflection on Ory's in particular. Beginning like the trombonist with a motivic statement, he “corrects” Ory's missed or ignored F7 changes in bars 2, 5-6.35 Then, after stating Lil's motive on the second half of bar 6 as Ory had done, Armstrong elects to leave the D# unresolved, thus transforming the pitch into a blue third (Eb) against tonic harmony in bar 7—a clever thwarting of a voice-leading expectation (D#-E) introduced by St. Cyr in his opening solo and repeatedly reinforced by all succeeding soloists.

Armstrong's solo tag after the final ensemble chorus summarizes and synthesizes “Gut Bucket Blues” rhythmically, melodically, and harmonically (Example 3). With a combination of syncopated and unsyncopated rhythms beginning with a characteristic rip up to high A on beat 4, he recalls the blue third and blue seventh, the A-Eb tritone, and the Eb/E conflict so central to the piece. Such details of nuance and creativity thus distinguish Armstrong from the rest of the Hot Five and serve as a prelude to his increasing musical dominance of the later recordings.

Example 3: Armstrong's solo tag in “Gut Bucket Blues”

IV: Coda

Except for a single public performance for publicity purposes36 the Hot Five was strictly a studio band throughout its existence while undergoing two major incarnations. For five sessions in May 1927, the Hot Five became the Hot Seven with the addition of tuba and drums, and in June-July 1928 Armstrong replaced the four original members and added drums to make the Hot Five, in numbers if not in name, a “Hot Six.”

The second Hot Five session on February 22, 1926 yielded a somewhat maligned performance of Luis Russell's and Paul Barbarin's “Come Back Sweet Papa,”37 but the third session four days later made Armstrong a star. Three of its six selections became jazz classics: Kid Ory's “Muskrat Ramble,”38 Armstrong's own “Cornet Chop Suey,” and Boyd Adkins' “Heebie Jeebies.” Armstrong's first recorded vocal and improvised scatting on “Heebie Jeebies” in particular caused a sensation. After its release in May, and for months thereafter “you would hear cats greeting each other with Louis's riffs when they met around town--'I got the heebies' one would yell out, and the other would answer 'I got the jeebies,' and the next minute they were scatting in each other's face.”39 Reportedly selling 40,000 copies, the record was the first Hot Five hit and the first to attract a substantial white audience. Its popularity prompted the publication of a sheet music version, additional recordings by singers of both races, and the creation of an associated dance which competed with the Charleston and Black Bottom in contests across the country. Soon fans were purchasing Heebie Jeebies shoes, doffing Heebie Jeebies hats, and devouring Heebie Jeebies sandwiches.40

More classics followed--”Big Butter and Egg Man,” “Wild Man Blues,” “Potato Head Blues,” “Struttin' With Some Barbeque,” “Hotter Than That,” “West End Blues,” “Weather Bird”--each to be subsequently and repeatedly anthologized, analyzed, and acclaimed as masterpieces of their kind. Each, too, reflected the musical characteristics first displayed in “Gut Bucket Blues” while comprising only the most conspicuous portion of a priceless legacy indebted to the fortuitous circumstances that united a “tin-eared” record executive with “the world's greatest jazz cornetist.”

Endnotes

1A somewhat unexpected problem in dealing with Armstrong's Hot Fives and Hot Sevens is determining the body of literature to be considered. In addition to the fifty-three titles released as Hot Fives or Hot Sevens between November 1925 and July 1928, Armstrong recorded almost two dozen more with the same or similar personnel/instrumentation as Lil's Hot Shots, Johnny Dodd's Black Bottom Stompers, Jimmy Bertrand's Washboard Wizards, Carroll Dickerson's Savoyagers, Armstrong's Stompers, Armstrong's Orchestra, and Armstrong's Savoy Ballroom Five. Some or all of these groups and more besides have been considered by various authors and compilers to fall under the Hot Five/Hot Seven rubric. The most inclusive collection yet, Louis Armstrong: The Complete Hot Five and Hot Seven Recordings (Sony Music Entertainment Inc., 2000), contains, with alternate takes, eighty-nine cuts.

2Andre Hodeir, Jazz, Its Evolution and Essence, trans. David Noakes (New York: Grove Press, 1956), 49, 62.

3Gary Giddins, Satchmo (New York: Doubleday, 1988), 86; James Collier, Louis Armstrong, An American Genius (New York: Oxford University, 1983).

4Talking Machine World [hereafter TMW] 19/7 (June 15, 1923), 73; TMW 19/8 (August 15, 1923),103; William Kenney, Chicago Jazz: A Cultural History, 1904-1930 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), 131. The Creole Band, probably representing Gennett for which they recorded in April, was the only black band on the program that included, among others, Benson's Orchestra (Victor), Albert E. Short's Tivoli Syncopators (Vocalion), Guyon's Paradise Orchestra (Okeh), Yerkes' S. S. Flotilla Orchestra (Vocalion), and Isham Jones' Orchestra (Brunswick).

5TMW 19/9 (September 15, 1923), 102.

7For the “Crazy Blues” story, see Samuel B. Charters and Leonard Kunstadt, Jazz: A History of the New York Scene (Garden City, N. Y.: Doubleday, 1962), 82-94; David A. Jasen and Gene Jones, Spreadin' Rhythm Around: Black Songwriters, 1880-1930 (New York: Schirmer, 1998), 263-269; and Brian Rust, The American Record Label Book (New York: Da Capo Press, 1984), 212-217.

8TMW 20/2 (February 15, 1924), 120; 21/5 (May 15, 1925), 1; 22/1 (January 15, 1926), 1; Lillian Borgeson, “Interview with Ralph Peer,” (January – May, 1958). Okeh's first TMW ad for electronic recordings appeared in the April 1927 issue, calling into question Panassie's claim of the process being used on the Hot Five cuts the previous November (Hugues Panassie, Louis Armstrong [New York: Charles Scribner, 1972], 73). The earliest electrical jazz recordings commercially released may have been the Jelly Roll Morton and King Oliver duets cut around December, 1924 by Autograph (Laurie Wright, Mr. Jelly Lord [Chigwell, Essex: Storyville, 1980], 30; Rust, The American Record Label Book, 21-22).

9TMW 14/12 (December 15, 1918), 90; 19/6 (June 15, 1923), 73; 19/10 (October 15, 1923), 58; E. A. Fearn entry, 1920 Census-United States, City of Chicago, E. D. 1692; E. A. Fearn obituary, Alton [Illinois] Evening Telegraph (July 20, 1953). Although native to Illinois, Fearn's family may have resided for a time in Kansas, where his older brother John was born according to his obituary in TMW 21/4 (April 15, 1925), 132.

10TMW 19/6 (June 15, 1923), 104; 19/11 (November 15, 1923), 112-114; 20/1 (January 15, 1924), 120; 20/2 (February 15, 1924), 120-121; 20/5 (May 15, 1924)120; 21/6 (June 15, 1925), 115.

11Chicago Defender, September 9, 1922 and February 16, 1924; Louis Armstrong, Louis Armstrong, In His Own Words, Thomas Brothers, ed. (New York: Oxford University, 1999), 86, 91; Lil Armstrong, “Satchmo and Me,” Riverside RLP 12-120. For the Oliver Band tour, see Walter Allen and Brian Rust, “King” Oliver, rev. Laurie Wright (Chigwell, Essex: Storyville, 1987), 38-41.

12Louis Armstrong, in His Own Words, 94; Chicago Defender, City Edition (November 7, 1925).

13Lil Armstrong, “Satchmo and Me”; TMW 21/11 (November 15, 1925), 134; TMW 22/5 (May 15, 1925), 134; TMW 22/5 (May 15, 1927),108; Collier, 179, 203-205. Rockwell's move to Okeh was undoubtedly connected with Columbia's purchase of the Okeh-Odeon record division from Heineman's General Phonograph Corporation in late 1926 (TMW 22/11 [November 15, 1926], 1).

14Max Jones and John Chilton, Louis: The Louis Armstrong Story, 1900-1971 (New York: Da Capo, 1988), 114; TMW 19/11 (November 15, 1923), 114; Bill Russell, New Orleans Style (New Orleans: Jazzology, 1994), 70; Ann Banks, ed., First Person America (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1980), 227. See also note 36.

15St. Cyr played a hybrid guitar-banjo purchased in 1919 which he used on all his Hot Five recordings (Johnny St. Cyr, “Jazz As I Remember It, Part Three: The Riverboats,” Jazz Journal 19/11 [November, 1966], 9). On the guitar-banjo see John Bright, “Idle Musings on a Banjo Theme: Johnny St. Cyr,” New Orleans Music 8/4 (December, 1999), 6-9.

16Johnny St. Cyr, “The Original Hot Five,” Second Line 5/9-10 (September-October, 1955), 1.

17Louis Armstrong, in His Own Words, 130.

18Christopher Hillman and Roy Middleton, Richard M. Jones: Forgotten Men of Jazz (Tavistock, England: Cygnet Publications, 1997), 8.

19Edward “Kid” Ory (as told to Lester Koenig), “The Hot Five Sessions,” The Record Changer (July-August, 1950), 17; Johnny St. Cyr, “Jazz As I Remember It, Part 4: Chicago Days,” Jazz Journal 20/1 (January, 1967), 15; Jones and Chilton, 114; Collier, 169-170. The relationship between Okeh and Consolidated Talking Machine is unclear. In the Defender Jones was called the “Western Recording Manager” for Consolidated Music Publishers (an apparent publisher of convenience for Consolidated Talking Machine Co.) during the time of the Hot Fives until he resigned the “dictatorship of the race record department” in early 1927 (Chicago Defender, November 6, 1926; February 19, 1927). By the time of the Hot Sevens Jones was on the staff of Okeh which was now a subsidiary of Columbia (Chicago Defender, May 7, 1927).

20Ory, Ibid.

21Hillman and Middleton, 10.

22TMW 21/12 (December 15, 1925); Borgeson, “Interview with Ralph Peer”; Ronald Foreman, “Jazz and Race Records, 1920-32” Their Origins and Their Significance for the Record Industry and Society” (Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Illinois, 1968), 92.

23 Borgeson, “Interview with Ralph Peer.”

24New Orleans Style, 71; Louis Armstrong, Swing That Music (New York: Da Capo, 1993), 85.

25Ory, “The Hot Five Sessions,” 17, 45.

26See Rick Kennedy, Jelly Roll, Bix, and Hoagy (Bloomington: Indiana University, 1994), no page number, for illustrations of Bix Beiderbecke and the Rhythm Jugglers making acoustic recordings for Gennett in 1925.

27St. Cyr, “The Original Hot Five,” 1-2; Bill Russell interview of Lil Armstrong, Chicago, July 1, 1959, Tulane Jazz Archive.

28Ory, “The Hot Five Sessions,” 45.

29To the author's knowledge, this publicity photo of the original Hot Five has not been previously published in the United States. The author thanks Klaus-Uwe Dürr for this copy, which Mr. Dürr obtained from John Dodds Jr., eldest son of Johnny Dodds.

30Gunther Schuller, Early Jazz: Its Roots and Musical Development (New York: Oxford University, 1968), 98.

31St. Cyr, “The Original Hot Five,” 2.

32Interview with Bill Rand for WERE Radio, Cleveland, c. 1953 (Cassette 26, Louis Armstrong Archives, Queens College, New York).

33Louis Armstrong, “Gut Bucket Blues” Copyright Deposit, E640490, April 30, 1926, Music Division, Library of Congress. Although listed in the Music Division's catalog, the copyright deposit for “Gut Bucket Blues” cannot presently be located. The author thanks David Chevan for providing the photocopy reproduced in Illustration 1. The submission is in Lil Armstrong's hand according to Chevan, “Written Music in Early Jazz” (Ph. D. dissertation, CUNY, 1997), 273-274.

34All musical transcriptions in this article are by the author. Other published transcriptions of Armstrong's “Gut Bucket” solo are in Lee Castle, ed. and trans., Satchmo's Solos (New York: International, 1958), 12-13; Gerald Poe, “An Examination of Four Selected Solos Recorded by Louis Armstrong Between 1925-1928,” NACWPI Journal (Fall, 1975), 3-5; and Peter Ecklund, ed. and trans., Louis Armstrong: Great Trumpet Solos (New York: Charles Colin, 1995), 4. A transcription of Johnny Dodd's solo is in Bill Russell, “Play That Thing, Mr. Johnny Dodds,” Jazz Information (August 23, 1940), 11. For evidence of King Oliver's influence on Armstrong's “Gut Bucket” solo, see Edward Brooks, Influence and Assimilation in Louis Armstrong's Cornet and Trumpet Work (1923-1928) (Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellen, 2000), 62.

35Armstrong's heightened sense of harmonic sensitivity in comparison to that of his musical colleagues is already evident on Chimes Blues, his first recorded solo with the Creole Jazz Band in 1923 (Schuller, Early Jazz, 83).

36Advertisements for the June 12, 1926 OKeh Cabaret and Style Show at the Chicago Coliseum organized by E. A. Fearn proclaimed that the Hot Five would perform several of its recent recordings and wax “Heebie Jeebies” live on stage (Chicago Defender, June 12, 1926), a publicity stunt employed before by OKeh in Detroit and New York City (TMW 21/2 [February 15, 1925], 118; TMW 21/10 [October 15, 1925], 92). Although the Hot Five “broke up the big ball June 12 with their hot playing,” the record-making demonstration apparently did not materialize (Chicago Defender, June 19, 1926). Armstrong seems to have appeared as a solo artist at the OKeh Race Record Artists Night, an earlier Fearn extravaganza on February 27, 1926 (Chicago Defender, January 30, 1926 and March 6, 1926).

37Hodeir, 52-53.

38Although copyrighted by Ory, Armstrong claimed composer credit in an interview with Dan Morgenstern in Downbeat (July 15, 1965), 18.

39Mezz Mezzrow and Bernard Wolfe, Really the Blues (New York: Citadel Press, 1990), 120.

40Collier, 173; TMW 22/11 (November 15, 1926), 128.