An Examination of the Latin American Stocks in the Library of Congress1

The mixing of Jazz with Latin American music during the 1930s and 40s initiated a reciprocal appropriation of performance styles by both American and Latin-American musicians. Some of the resultant fusions from this exchange include the Latin Jazz genres of Cubop and Salsa. While there have been some important studies on the repertoire, few have examined the primary sources that gave birth to these genres.2

Within the vast holdings of the Library of Congress, there are thousands of period arrangements of Latin American music for gran orquesta or big band. This paper examines a selection of repertoire for Latin American big band published from 1930 to 1959 with the aim to show how these primary sources can be used today in the performances of Latin big band repertoire. These sources are in the form of band stocks and include parts, not full score, for saxophones, trombones, trumpets, and rhythm section. Many of these were arranged by the leading musicians in their day, including Ernesto Duarte, Peruchín, and Pérez Prado. While there has been much interest in the performance and scholarship of Latin Jazz, these stocks remain for the most part unexamined or unused by performers and scholars.

This study begins with a broad description of the types of stock and their location within the Library of Congress. The next part of the paper discusses four broad areas of development that include repertoires from Argentina, Brazil, Cuba and Mexico. Because of space, this paper focuses only on the latter two, Cuba and Mexico. I then proceed to examine selected samples from the holdings drawn from composers of the period including Pérez Prado, Beny Moré, and Agustín Lara. Through this examination I intend to show the value that these stocks present to scholars and performers regarding the authentic performance practice of this repertoire: a repertoire that reflects the strongest American Jazz influence of all Latin American music, and helped in the creation of Latin Jazz genres.

Description of the Holdings

The following discussion considers a few of the investigative domains that aid in the understanding of the history, nature, status, and location of these sources. While the emphasis clearly reflects this writer's own interests, it should, nevertheless, provide an idea of the path one might take in locating and accessing similar sources for the purposes of performance or scholarship. These broader topics of investigation include deposited copyrighted sources, call numbers and location in the library stacks, and limitations or scope of the study. The latter includes the historical and stylistic ranges of a study. Finally, there is a discussion of the scoring of the stocks, along with a statement on the problem that arises due to the absence of scored percussion.

Ever since the formation of copyright, the Library of Congress has kept copies of all printed material under copyright for deposit. This includes the scores of band stocks that were published for use by dance orchestras during the Golden Age of Latin American music.3 As a result, copies of these scores held in the library are available for the purposes of study and performance. Because the library has thousands upon thousands of these Latin sources, there is, to date, no comprehensive inventory of these stocks, and bibliographic control of the material will depend on the interests of specialists who work in specific collections.

The holdings are deposited according to their Library of Congress classification, and then in alphabetical order by the composer's last name. Within the Library of Congress's classification of subject headings, these stocks are found primarily under the subject heading for reduced orchestra, M1350, and the subject heading for dance orchestras and instrumental ensembles, M1356. All the stocks are kept in boxes, and accessing the material requires that patrons page a box that includes the composer's works and rummage through the container until the desired scores are located. In some cases, the collected works of a composer may span several boxes. There is no online catalog reference to the complete sources, and the card catalogs provide only a small number of works that have been indexed. The most thorough examination requires that one know the name of the composer, call up the box that holds that composer's works, and go through the contents in order to see which works are there. Some of the more popular non-Latin holdings of band music have already been grouped and catalogued by reference librarians at the Library of Congress in order to make available certain significant collections of music. Some representative collections include the Count Basie Stocks and the Melrose Syncopation Series; the latter consisting of stocks from mostly before 1935 including works by King Oliver and "Jelly Roll" Morton.

Scope

Within the holdings of M1350s and M1356s, there are thousands of arrangements of Latin American big band music. Popular compositions like "El manicero," commonly known as "The Peanut Vendor," by Moises Simón may have as many as a dozen or more arrangements for big band. Because of the Library of Congress's charge to maintain copies of all music deposited under copyright, these holdings would include arrangements made outside of the professional Latin American dance band tradition. This could include versions of Latin works by American arrangers that were targeted, for example, to the amateur community band. I mention this diversity of arrangements because when searching for a version of a popular work such as Pérez Prado's "Que rico el mambo" one finds arrangements of varying quality among the holdings.

For my own work, I look for the versions that were recorded by the artists. If they were arrangements that were used by the performers or composers, I give them a special level of significance. So, for any particular composition, it helps to know which arrangement I'm looking for so that I may be able to identify it when searching among the holdings. Other criteria to locate more authentic versions also include searching for arrangements published in Latin America as well as the names of well-known arrangers of the period.

The sources under examination in this study consist of Latin American music arranged for dance orchestras between the years 1930 to 1959. Historically it begins with editions of tango music from Argentina, continues through the rumba and samba crazes that existed in the 1940s, and culminates in the popular genres of bolero, cha cha chá and mambo. While there are many arrangements from outside of Latin America, this study discusses the sources published by Mexican, Cuban, Argentine, and Brazilian publishers, since the versions I work with come from publishers in these locales. While sources exist prior to 1930, they are infrequently encountered among the holdings. Also, for the purposes of making connections among the most important composers, performers and arrangers, the most significant work begins after 1930 when Latin American music began its period of globalization. 1959 may be an obvious terminal point in that after the rise of Fidel Castro, the Cuban sources (which are quite extensive) drop off almost entirely. Also, beginning in the late 1950s one sees a decline in the production of Golden Age genres like the rumba and cha cha chá, as they begin to be replaced with more modern and international dance genres such as Blues, Hully Gully, Jerk, the Shrug, and of course Rock and Roll. The following are a list of Latin American publishers that were active during the period.

Table 1: Latin American publishers.

Argentina

Ediciones Musicales, Buenos Aires

Editorial Musical Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires

Editorial Saraceno, Buenos Aires

Fermata, Buenos Aires

Julio Korn, Buenos Aires

Ricordi, Buenos AiresBrazil

Irmaos Vitale, Rio de Janeiro

Irmaos Vitale, Sao Paulo

Todamerica Musica, Rio de JaneiroCuba

Continental, Havana

Editora Cubana de Música, Havana

Peer, Havana

Rumbalero, HavanaMexico

Editorial Mexicana de Música Internacional (EMMI), Mexico City

Hermanos Marquez, Mexico City

Promotora Hispanoamericana de Música (PHAM), Mexico City

Southern Music, Mexico City

The majority of the Latin American stocks are arranged for saxophones, trumpets, trombones, and a rhythm section that includes piano, bass, guitar and ad lib percussion. Early in the period, there were parts given for flute, violins, and clarinet, and toward the end of the period, parts for guitar are no longer included. There are also parts for conductor or guide that are usually in the form of a piano reduction, though sometimes they may be in the form of a lead sheet. The vocal parts, when included, consist of a separate sheet of words for the singer. The notation of the vocal parts is usually supplied in small notes in the piano part or the conductor's score, without any text underlay.

Percussion parts

A brief sideline on ad lib percussion in Latin American popular music: Presumably, the main interests in these scores are the parts provided for the complicated fabric of layered percussion that one hears in recordings. The percussion battery in Latin American dance music consisted of a variety of instruments such as clave, maracas, bongos, congas, güiro and timbales. A thorough study of sources would certainly intend to engage a detailed study of how these percussion parts are performed. Unfortunately, most of the stocks do not include any performance parts for these percussion instruments. The most that is ever included is a "drums" or batteria part that gives cues for break, and perhaps an occasional abanico or drum roll. Obviously, Latin American percussionists from the period required no music, and they were expected to already know how to play the appropriate time-line pattern for their instrument.4

Regional Examination of Stocks

What follows are a sample of various stocks from the period. While I will discuss some musical sources from South America, there is greater attention given to works in my own area of interest from Mexico and Cuba. After giving some broad information on the publishing centers, I move to some selected examples in order to show more closely what these stocks may have to offer in the way of performance and performance practice of Latin American big band repertoire. I introduce the history of the sources by way of the publishing centers because these four areas produced much of the published stocks during the period. Even within the relatively narrow range of dates, 1930 to 1959, there is evidence of many changing trends during the time span. Hence, one sees a variety of musical genres appearing, flourishing, and dying through publication trends. In Havana, one sees many different styles come and go. For example, early in the period, we see many congas published by Cuban publishers. Toward the end of the period, however, there are very few congas by comparison to the large number of mambos and cha cha chás being published as a result of the popularity of the latter two dance genres in the 1950s. Yet, while the genres may change over a period of time, most of the publishers favored the genres that were most popularly associated with that country (e.g. tangos in Argentina, sambas and chôros in Brazil, etc.). Mexican publishers proved to be an exception to this. With Mexico City being the center of Latin American culture for the first half of the 20th century, and relatively few influential Mexican genres, one sees most of the popular Latin American dance types published by Mexican publishers of the period.

Argentina and Brazil

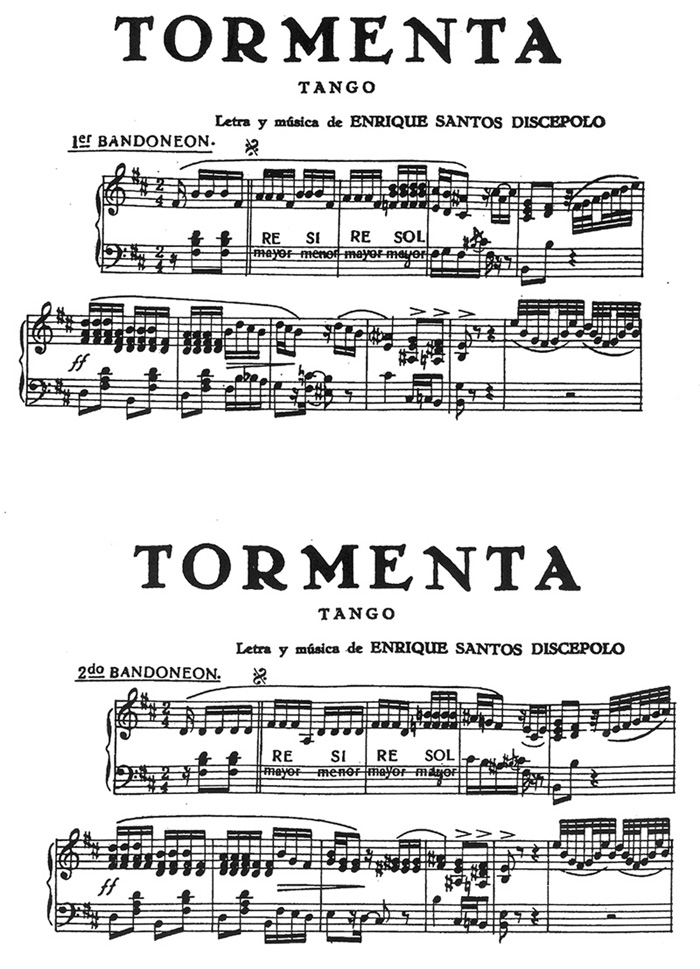

Among the earliest wave of published band parts are those from Argentina, which were a result of the massification of the tango that occurred through the 1930s. Most of these publishers were actively disseminating tangos from Buenos Aires. These sources are among the more unique in that they provide parts for violins, and bandoneon (the Argentine button accordion). While other Latin American publishers such as PHAM and Peer-Southern included tangos in their selection of stocks, they are not likely to have included the bandoneon parts, rather, they provided a standard big band arrangement that included a full set of saxes, brass, and rhythm section. Below is a portion of a bandoneon part taken from a stock from the tango repertoire. The piece is "Tormenta" by Enrique Santos Discepolo and was published by Editorial Julio Korn in 1939. The entire stock contains parts for piano, two bandoneons, three violins, cello, bass,  saxophone, and

saxophone, and  trumpet.

trumpet.

Figure 1: Bandoneon parts from "Tormenta" by Enrique Santos Discepolo.

Stocks from Brazilian publishers are numerous from about 1940 onward. Brazilian editions include the repertoire of sambas, maxixes, marchas, and batucadas. In the late 1930s and 40s, Irmaos Vitale published the majority of these sources. Most of these arrangements are scored for gran orquesta, but may also include parts for violin, flute, and clarinet. Notable among the holdings are a vast collection of works by Ary Barroso, some of which were arranged by Alfredo Vianna, who was known commonly as "Pixinguinha."

The music from Mexican and Cuban publishing houses shows a great degree of diversity among repertoire of the periods, and the choices of published repertoire follow the trends of musical popularity, not just in those locales, but throughout much of Latin America. Genres include: samba, tango, rumba, guaracha, bolero, conga, cha cha chá, mambo, canción, and Afro, among the standard types, as well as all the hybrids, bolero-cha, bolero-son, bolero-mambo, etc.

In the following section, the discussion shifts to a more detailed examination of selected pieces from the period. I begin by examining parts from a Mexican bolero arranged for gran orquesta. This allows us to see some of the details of a typical arrangement more closely. I then continue with an examination of a Cuban bolero that includes a couple of vamps at the end of the score that require some explanation regarding their performance practice. This veer into performance practice continues with a look at a Cuban mambo from the 1950s that shows how performing directions in the score inform our understanding of group vocal performance in a predominantly instrumental work. By looking at these three selected scores, we may better understand the structure and arrangement of the sources, as well as the implications for performance practice based on the information provided.

Mexico

Solamente una vez

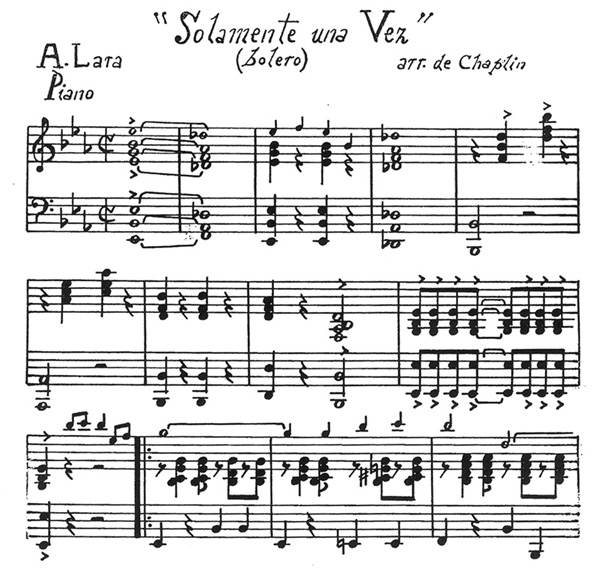

The following piece is a bolero from Mexico by Agustín Lara entitled "Solamente una vez." The piece was published in 1941 by P.H.A.M. with an arrangement by "Chaplin," which was a nom de plum for Felix Santana, a well-known arranger and composer of the period. This score is arranged for piano, three violins, four saxophones, three trumpets, two trombones, bass, and drums. As expected the vocal part is included in smaller notes in the piano part with a separate sheet for the lyrics.

Below is a portion of the piano part, which after the instrumental introduction plays a bolero accompaniment pattern during the vocals—a syncopated right hand against bass notes on beats one, three, and four. This is unlike reduction piano parts that might try and provide a composite of the band parts. Notice also the vocal line in smaller notes beginning in the third system.

Figure 2: Piano part to "Solamente una vez" illustrating a bolero rhythm, and the textless vocal part.

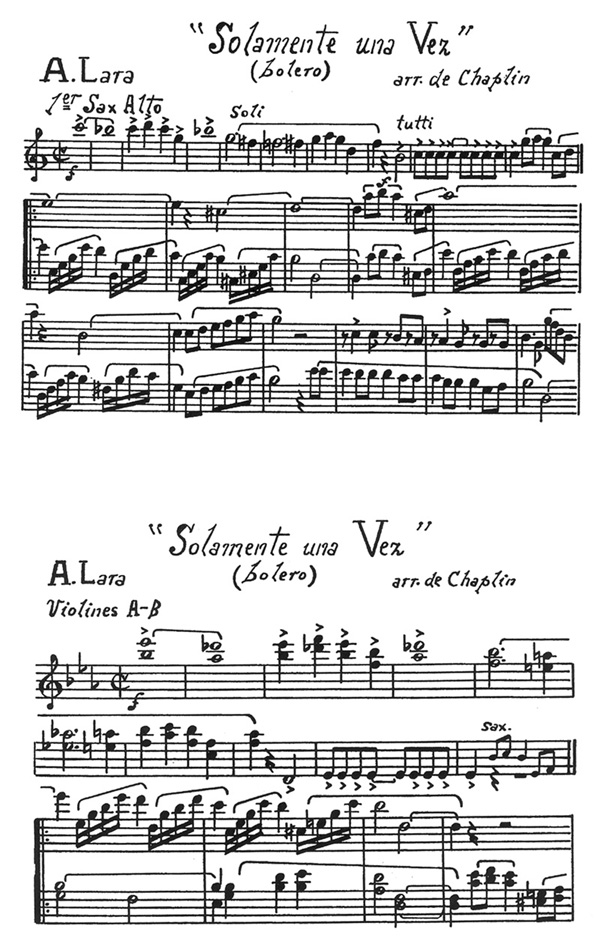

A comparison of the 1st alto saxophone and the divisi violin parts allows us to see some of the scoring during the vocal section. Notable is the exchange of the main melody and obbligato accompaniment pattern at the repeat. There are a couple of performance possibilities in this example. On the one hand, it could be used in purely instrumental performance of this song. On the other hand, it could also suggest an instrumental arrangement of the lead melody to be used during an interlude of the song.

Figure 3: Saxophone and div. violin parts illustrating lead melody/accompaniment relationships.

The drum part in "Solamente una vez" gives us an example of a typical skeletal percussion part. During the instrumental introduction, the part accents the rhythms of the instrumental parts. Beginning in measure 11, during the song proper, the drums show a rather basic reduction of the piano's rhythmic accompaniment pattern. This holding pattern is repeated in the score until the first break at measure 27, where an important break is cued in the score. The purpose of the part, too simple for any professional percussionist, is given to illustrate the breaks in the music, and any specific rhythm that contrasts from the bolero holding pattern.

Figure 4: Excerpt from the drum part to "Solamente una vez."

Lara's published works arranged for gran orquesta are quite numerous as during the period he was Mexico's greatest composer of popular songs. This one example from Mexico represents a typical Mexican bolero arrangement from the period, but a broader view shows how in Mexico, publishers released many international genres, which show the cosmopolitan influence on music dissemination that Mexican publishers were charged with in the first half of the 20th Century. Table 2 shows a short sample of the breadth of works from Mexican publishers between 1930 and 1959. This is in contrast to the music published by Cuban presses from the same period, which show a diversity of genres and styles, albeit from a local perspective.

Cuba

Amor sin fé

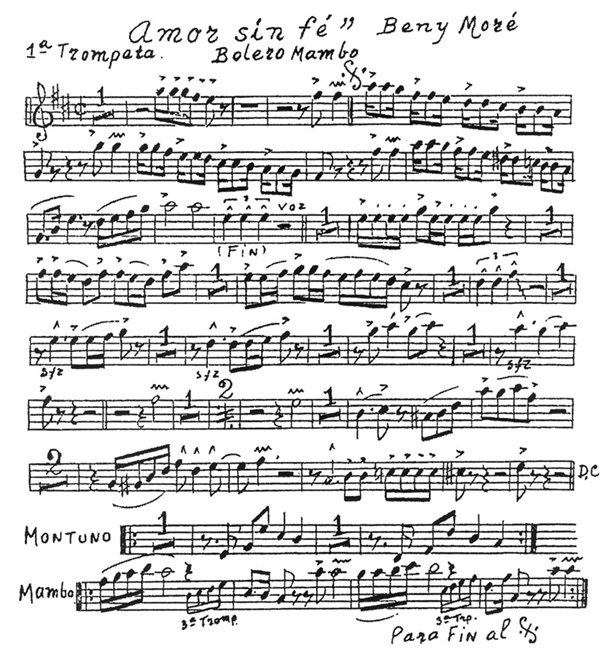

The next example is a bolero-mambo by Cuban composer and singer, Beny Moré. The work was published in 1953 by Peer-Havana, and was arranged by Ernesto R. Duarte. By now, the standard orchestration for big band or gran orquesta consists of five saxophones (two altos, two tenors, and a baritone), four trumpets, two trombones, piano, bass and ad lib percussion. The arrangement adheres to the Cuban three-part structure of song (which presents the theme or main melodies), montuno (during which there is a leader/group alternation between soloist and chorus) and mambo section (which featured a textured horn or saxophone section that was usually inserted between the previous two sections). Below is a portion of the 1st Trumpet part that shows the three sections of the piece. The first seven staves include the instrumental introduction and the song, which begins at measure 12, as is evidenced by the word "voz," which indicates the beginning of the vocal part. The eighth and ninth staves show the montuno and mambo vamps, respectively.

Figure 5: Trumpet part to "Amor sin fé" with montuno and mambo sections.

In the recorded Moré performance, "Amor sin fé" goes through the main song once and then moves directly to the four-measure montuno section, where the chorus alternates their refrain with vocal improvisation from the lead singer, in this case it is Moré himself. This section is performed four times with the chorus introducing the montuno prior to the improvised lead. The mambo section, which features layered horn lines called moñas, follows this. After the mambo section, the montuno returns with leader-group alternation for three more cycles, after which the song goes to a D.S. al fine (labeled a D.C. in the score).

In comparing the two previous bolero types from Mexican and Cuban sources, one notices a difference between the Mexican bolero by Lara and the Cuban bolero by Moré: not only the arrangement, but also the presence of Cuban elements like the montuno and mambo sections. The Moré retains the Afro-Cuban style of leader-group alternation in the montuno section, as well as the mambo section, which showcases the horns. The Lara arrangement follows the Mexican style performance for the bolero, which is more of a straight-ahead ballad style using the bolero rhythm. This style, which was made famous in Mexico by Lara, eventually became the dominant style of bolero performance in the late forties and fifties through its appropriation and international proliferation abroad by trios like Los Panchos.5

Cuba (via Mexico)

Que rico el mambo

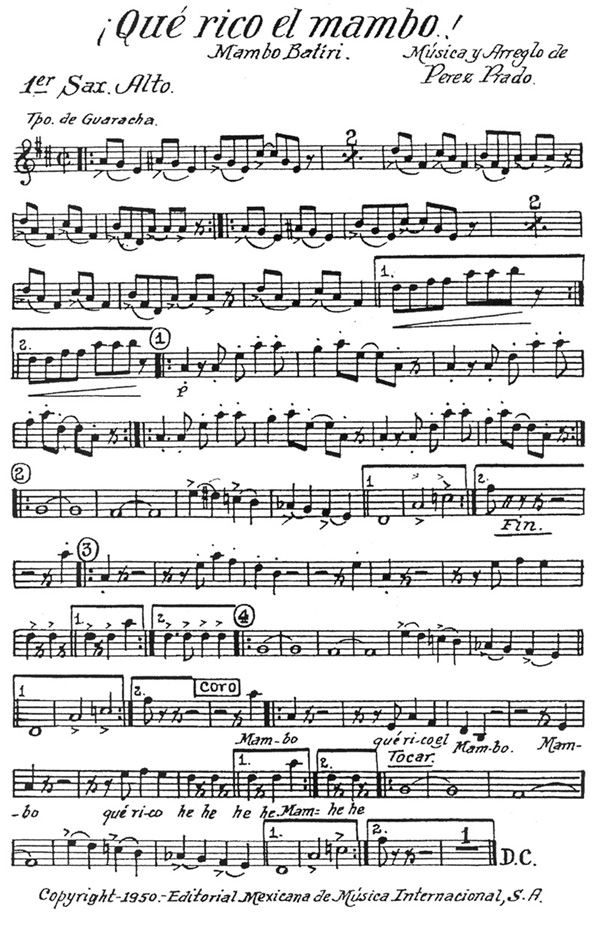

The next score from the period is "Que rico el mambo" written and arranged by Pérez Prado in 1950. This is an example of a Cuban band piece that was published in Mexico by EMMI. For professional reasons, Prado, the "Mambo King," left Cuba in 1949 for Mexico. There, as well as composing and performing, he was also featured in Mexican movies as an on-screen performer.

Figure 6: 1st Saxophone part to "Qué rico el mambo!" with text underlay and "Tocar" directions.

This piece is by far his most popular work, and became the standard mambo tune of its day. Unlike the sung mambos of Moré and other Cuban composers of the late forties and fifties, Prado excelled in an almost purely instrumental mambo style. The exception to this is the montuno toward the end of the performance where the chorus repeats the refrain "mambo, que rico el mambo." The notation during this chorus provides the montuno melody with the text underlay, which is unlike the typical notation of a vocal part. When the montuno ends, the text "Tocar," which means to play, suggests that instrumentalists like the saxophone were expected to join in singing during the chorus. This shows how these stocks are not only useful as parts, but contain important clues to performance practice.

The preceding two pieces by Cuban composers Moré and Prado demonstrate some of the details regarding performance practice that these scores offer, and the discussion of these examples presumes an adherence to the arranged parts. However, there is no reason to assume that smaller ensembles could not benefit from the structural form of the arrangements. In a recent acquisition, I inherited some personal stocks from the celebrated band leader Russel M. Goudey, who himself was active as a composer and arranger during the 1940s and 50s. In many of the scores I have found a redistribution of parts to be played by whoever was available for the individual part. In some cases the arrangement for big band was reduced to an arrangement for a quintet. The following looks at ways of tailoring these sources for smaller ensembles and also offers an alternative to the vocal leader-group alternation during the montuno section.

Performance Considerations

The sources of Latin American band stocks offer an opportunity for flexibility in performance. It is not necessary to have a complete saxophone or trumpet section to play from the scores. Indeed, it was certainly the case that certain parts may have been transposed and re-assigned in order to suit the needs of the dance ensemble. What is important is maintaining the basic texture of the pieces. For example, in the Moré example "Amor sin fé," the basic layers of activity are:

Vocal melody (playable on any lead melody instrument)

Two-measure accompanying montuno pattern in the saxophones

Punctuation of phrases (provided by the brass)

Bass

Ad-lib percussion

As long as these basic functions are maintained, the integrity of the arrangement remains intact. What this means for performance is that these sources of Latin music need not necessarily be reserved for performances by large, fully orchestrated forces. With a creative reassigning of parts, the music of any of these historical arrangements may be transferred to modern ensembles and still produce an authentic performance of a period arrangement.

Another performance consideration would be the use of instrumental improvisation during the vocal montuno section. In the Moré example, the montuno alternates between a group chorus and an improvised lead singer. It is completely reasonable to perform instrumental improvisation during these montuno sections between the declamations of the chorus. Consider the well-known piece "Mango mangue," by Machito and his Afro Cubans with Charlie Parker on saxophone from 1948.6 In this recording Parker takes the role of the vocal lead as he improvises between the montuno chorus. In the recording the chorus chants a two-measure "Manguito mangue" montuno. Normally a vocal montuno would demonstrate the singer's ability to extemporize text and melody. When played by a solo instrument, as in this Parker example, all of the attention is towards the melodic inventiveness. Interestingly, Parker's improvisations do not stay within the two measure confines determined by the length of the montuno, and at times his phrases continue into the succeeding declamations of the chorus. While this sort of continued overlap may result in a confused declamation of texts, it is not inappropriate for an instrumentalist, whereas a texted improvisation might stay more within the montuno phrase, lest there be conflicting texts between the soloist and the chorus.

The preceding two discussions show that although these sources are arranged and scored with a particular ensemble in mind, there is also room for flexibility in performance. These sources were not only published to provide a full set of parts for large ensembles that had the requisite forces, but also as resources for bandleaders and arrangers who tailored the parts to suit the needs of their ensembles and still retain the essence of the arrangements.

* * *

The sources discussed in this paper consist of four areas within the large number of the Library of Congress's Latin American band holdings. There are many different areas within these groups, and there remains a need for a major study on any one of them. Much work in the area of bibliographic control over selected areas should be conducted before further studies commence. Aside from the four geographic areas presented in this essay, there are also other groups of smaller repertoires by composers from Colombia, Haiti, and The Dominican Republic. But whatever the repertoire, if the sources were deposited for copyright, it is quite likely that there is at least one copy in the Music Division of the Library of Congress, whether the piece is still under copyright or not. Such a vast collection offers much to be gained from accessing and utilizing these vital, yet relatively unknown sources.

Table 2. Selected Sources for Latin American gran orquesta*

- Arrondo, Juan. Que pena me da. Bolero. Arr. Eduardo Cabrera. Havana: Peer, 1953.

- Call no.: m1356.A.

Notes:major

- __________. Salsa y bistec. Rumba-cha. Arr. Pepe Delgado. Havana: Peer, 1956.

- Call no.: M1356.A.

Notes:major

- Cabrera, Ramón. Manzanillo. Son montuno. Arr. Peruchín. Havana: Peer, 1953.

- Call no.: M1356.C.

Notes: C major- __________. Santiago de Cuba. Son montuno. Arr. E. Cabrera. Havana: Peer, 1954.

- Call no.: M1356.C.

Notes: C major- Cardenas, Felix. Puntillita. Son montuno. Arr. Pérez Prado. Havana: Peer, 1946.

- Call no.: M1356.C.

- Notes: F major

- Carrillo, Alvaro. Sabor a mí. Bolero. Arr. Rodolfo Villavazo Fernandez. Mexico City: PHAM, 1959.

- Call no.: M1356.C.

- Notes:

major; includes separate parts for 3 violins, viola and cello; separate part for director.

- Collazo, Bobby. Cha cha cha bar. Cha cha chá. Arr. Rafael Somavilla. Havana: Continental, 1954.

- Call no.: M1356.C.

- Notes:

major; separate part for director.

- __________. Serenata mulata. Fantasia antillana. Arr. Bobby Collazo. Havana: Peer, 1958.

- Call no.: M1356.C.

- Notes: e minor, G major; includes parts for 3 violins. Separate part for director; This "fantasia" consists of an introduction then moves from a tpo. de Afro to tpo. de beguine to a tpo. de mambo.

- Gil, Alfredo. Ni que si, ni quizá, ni que no. Bolero. Arr. E. Tafoya. Mexico City: PHAM, 1950.

- Call no.: M1356.G.

- Notes: f minor; includes parts for 3 violins and cello; separate conductor score.

- Gonzalez, Virgilio. Cachumba. Guaracha. Arr. Virgilio Gonzalez. Havana: Peer, N.D.

- Call no.: M1356.G.

- Notes: G major

- Hernandez, Rafael. Desvelo de amor. Rumba. Arr. Joe Pafumy. Mexico City: Southern Music, 1937.

- Call no.: M1350.H.

- Notes: g minor, G major,

major; includes parts for 3 violins and guitar with chord designations and slash notation.

- __________. El Cumbanchero. Conga. Arr. Felix Santana (Chaplin). Mexico City: PHAM, 1943.

- Call no.: M1350.H.

- Notes: E minor; includes 3 violin parts.

- López, Israel and Rafael Ortiz. Hasta cuando. Son montuno. Arr. Pérez Prado (El Rey del Mambo). Havana: Peer, 1947.

- Call no.: M1356.L.

- Notes: d minor

- Moré, Beny. Amor sin fé. Bolero mambo. Arr. Ernesto R. Duarte. Havana: Peer, 1953.

- Call no.: M1356.M.

- Notes: C major

- __________. Bonito y sabroso. Mambo. Arr. Rafael de la Paz. Mexico City: EMMI, 1953.

- Call no.: M1356.M.

- Notes:

major

- __________. Locas por el mambo. Mambo. Arr. Pérez Prado. Mexico City: EMMI, 1951.

- Call no.: M1356.M.

- Notes:

major.

- Rodriguez, Arsenio. Titi tu kundungo quiere papa. Cha cha chá. Arr. J. Claro Fumero. Havana: Peer, 1956.

- Call no.: M1356.R.

- Notes:

major

- Ruiz, Gabriel. Usted. Beguine. Arr. Toño Guzmán. Mexico City: PHAM, 1951.

- Call no.: M1356.R.

- Notes:

major,

major, and

major; includes parts for 3 violins, viola, and cello.

*Unless otherwise noted, the stocks use an instrumentation of trumpets; trombones; alto, tenor, and often, baritone saxophones; piano, bass and ad lib percussion. Almost all of the stocks include text for the vocalist. If provided, the director's part is usually in the piano part.

1"Stocks" are stock arrangements for big band or dance orchestra that include a full set of parts. I am grateful to Mr. Wayne Shirley, Music Specialist at the Music Division of the Library of Congress, for bringing these sources to my attention and for being very generous with his knowledge of sources.

2Notable among these studies are Lise Waxer, The City of Musical Memory: Records, Salsa Grooves and Local Popular Culture in Colombia (Hanover, NH: University Press of New England, for Wesleyan University Press, forthcoming 2002); and Situating Salsa: Global Markets and Local Meanings in Latin Popular Music, ed. Lise Waxer (New York: Routledge, 2002); John Storm Roberts, Latin Jazz: The First of the Fusions, 1880s to Today (New York: Schirmer, 1999); Steven Loza, Tito Puente and the Making of Latin Music (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1999); Christopher J. Washburne, "Salsa in New York: A Musical Ethnography" (unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Columbia University, 1999); Frances Aparicio, Listening to Salsa: Gender, Latin popular music, and Puerto Rican Cultures (Hanover, NH: University Press of New England, 1998).

3For a discussion on the history of acquisitions in the Music Division at the Library of Congress, including the historical relationship between copyright deposit and collection development see Gillian Anderson, "Putting the Experience of the World at the Nation's Command: Music at the Library of Congress, 1800-1917," Journal of the American Musicological Society 42: 1 (Spring 1989), pp. 108-144. For a study of copyright as it pertains to the music industry see David J. Moser, Music Copyright for the New Millennium (Vallejo, California: ProMusic Press, 2002).

4An exception to this are the Latin American stocks targeted at an American audience, which provide a more detailed part. A series of Brazilian compositions published in Havana (with Spanish texts!) and marketed in English through Robbins Music Co. include detailed percussion instructions in the drum part of the orchestration.

For a detailed look at layered percussion parts for period dances such as son, cha cha chá, and mambo, the reader is referred to Humberto Morales' publication Latin-American Rhythm Instruments and How to Play Them (New York: Belwin Mills, 1954 [renewed 1982]). More recent publications include Rebecca Mauleon, The Salsa Guidebook (New York: Sher Music Co., 1993); and Ed Uribe, The Essence of Afro-Cuban Percussion and Drum Set (New York: Warner Brothers, 1996).

5For further reading on the bolero see George Torres, "The Bolero Romántico: From Cuban Dance to International Popular Song," in From Tejano to Tango: Latin American Popular Music, edited by Walter Aaron Clark (New York: Routledge, 2002), pp. 151-171.

6The following comments are based on the recording "Mango Mangue," South Of The Border, 1948-52; Verve 527779.