Introduction

It would be difficult to overstate the impact the blues had on American music in the twentieth century. In his 1993 book, The Land Where the Blues Began, Alan Lomax states,

Although this has been called the age of anxiety, it might better be termed the century of the blues, after the moody song style that was born sometime around 1900 in the Mississippi Delta. . . . Nowadays everyone sings and dances to bluesy music, and the mighty river of the blues uncoils in the ear of the planet.1

Lomax also notes, "Every one of the world-renowned black American genres from ragtime to rap bears the mark of this 'folk' heritage."2 One reason the blues form has exerted such far-reaching influence has been its ability to morph in order to suit a wide variety of musical visions, a malleability that can clearly be seen in jazz. From the early rural blues, to the urban blues of the 1920s, to the use of the blues in modern-day jazz, the form has exhibited notable flexibility while still retaining its basic structure. I will discuss this characteristic through the use of descriptive analyses of recordings that represent early jazz, big band jazz, bebop, hard bop, free jazz, modal jazz, and the jazz of the last thirty years. The artists who will be discussed are Ma Rainey, Jimmy Rushing with the Count Basie Orchestra, Charlie Parker, Horace Silver, Eric Dolphy, Chick Corea, Dave Holland, The Dirty Dozen Brass Band, and Carla Bley.3 In addition, this article will briefly examine the roots of the blues and explain what defines the blues.

The Twelve-Bar Blues: Background Information

The roots of the blues predate the phonograph and other sound reproduction devices4 and there is no known written notation of the earliest blues. "The African music from which the blues ultimately derives came to what is now the southern United States with the first African slaves."5 Even though slaves were largely prevented from singing the music from their homelands, the musical forms that they were permitted to perform were imbued with African performance practices. These nineteenth-century precursors to the blues include field hollers, work songs, folk ballads, ring shouts, and spirituals. Around the 1890s, the country blues form began to coalesce. Other forms that continued to shape the blues beyond this decade include vaudeville songs, ragtime,6 and minstrel songs. "Blues certainly had roots in earlier Southern styles, but its trunk and many of its most fruitful branches were in Chicago and New York—and later in Los Angeles—in the recording studios and vaudeville theaters."7

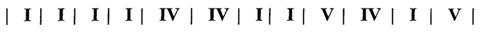

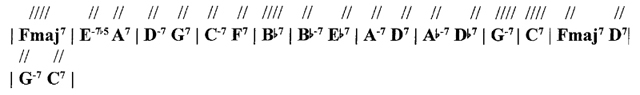

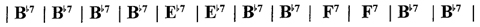

Though some eight-bar, sixteen-bar, and other variations exist, this paper will concentrate on the form most commonly heard in jazz, the twelve-bar blues. Harmonically, one of the frequently-heard early twelve-bar blues looks like this:

A well-known example of this harmonic progression can be heard in the 1936 Robert Johnson recording, "I Believe I'll Dust My Broom." By the time Johnson had made this record, countless urban and country blues performers had been using this twelve-bar blues form as a vehicle for vocal and instrumental story telling. I have chosen to highlight this particular recording because it so clearly exhibits the harmonic and lyric schemes that will be discussed in this article.

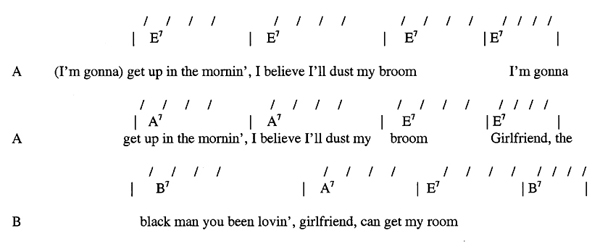

The lyrics that are sung over the chords shown above consist of a four-bar phrase which is repeated and then answered by a second four-bar phrase. This creates an AAB vocal pattern that is clearly seen in Johnson's blues:

| A | I'm gonna get up in the mornin', I believe I'll dust my broom | |

| A | I'm gonna get up in the mornin', I believe I'll dust my broom | |

| B | Girlfriend, the black man you been lovin', girlfriend, can get my room | |

| A | I'm gonna write a letter, telephone every town I know | |

| A | I'm gonna write a letter, telephone every town I know | |

| B | If I can't find her in West Helena, she must be in East Monroe, I know | |

| A | I don't want no woman, wants every downtown man she meet | |

| A | I don't want no woman, wants every downtown man she meet | |

| B | She's a no good doney, they shouldn't allow her on the street | |

| A | I believe, I believe I'll go back home | |

| A | I believe, I believe I'll go back home | |

| B | You can mistreat me here, babe, but you can't when I go home | |

| A | And I'm gettin' up in the mornin', I believe I'll dust my broom | |

| A | I'm gettin' up in the mornin', I believe I'll dust my broom | |

| B | Girlfriend, the black man you been lovin', girlfriend, can get my room | |

| A | I'm gonna call up Chiney, she is my good girl over there | |

| A | I'm gonna call up China, she is my good girl over there | |

| B | If I can't find her on Phillipine's Island, she must be in Ethiopia somewhere8 |

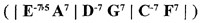

As seen below, the first vocal line (A) is sung over the I chord. When it is repeated, it begins over the IV chord. The reply (B) begins on the V chord and resolves back to the I chord. This configuration creates a simple and effective dramatic device: When the first line of the song is repeated, the harmony changes, adding emphasis to the lyrics' content. The reply (B) occurs over the V chord which creates the most tension and allows for a resolution on the I chord at the end of the verse9:

This configuration is representative of a template that continues to be used by blues musicians to this day. More importantly for the sake of this paper, this structure became the foundation on which innumerable jazz pieces were written.

A Sampling of Recorded Jazz from a Variety of Style Periods That Utilizes the Twelve-Bar Blues

Since its conception, jazz was a vehicle for group improvisation in the 1920s; a popular dance music in the 1930s; a showcase for individual virtuoso improvisers in the 1940s; a groove-oriented music in the 1950s; a protest medium in the 1960s; part of a fusion partnership with rock in the 1970s; and an often highly cross-pollinated and stylistically splintered genre over the last thirty years. While labeling the style periods of jazz in this manner greatly oversimplifies matters, it is one way of making some sense out of a complex, ever-evolving art form.

A good demonstration of group improvisation in jazz can be heard in Ma Rainey's 1924 recording of "Booze and Blues," which retains the twelve-bar form and AAB vocal scheme found in the earlier country blues:

| A | Went to bed last night, at four o'clock I was in my beer | |

| A | Went to bed last night, at four o'clock I was in my beer | |

| B | Woke up this mornin', the police was shakin' me | |

| A | I went to the jailhouse, drunk and blue as I could be | |

| A | I went to the jailhouse, drunk and blue as I could be | |

| B | But that cruel old judge sent my man away from me | |

| A | They carried me to the courthouse, oh Lordy how I was cryin' | |

| A | They carried me to the courthouse, oh Lordy how I was cryin' | |

| B | They gave me sixty days in jail and money couldn't pay my fine | |

| A | Sixty days ain't long when you can spend them as you choose | |

| A | Sixty days ain't long when you can spend them as you choose | |

| B | But they seemed like years in a cell where there ain't no booze | |

| A | My life is full of misery when I cannot get my booze | |

| A | My life is full of misery when I cannot get my booze | |

| B | I can't live without my liquor, got to have the booze to kill these blues |

In addition to being an excellent example of an urban blues, "Booze and Blues" is unmistakably a jazz piece as well. The banjo player keeps a steady pulse while the trombone, clarinet, and cornet players expertly improvise around Rainey's singing without interfering with the lyrics or each other. The improvisation is done in the polyphonic style of 1920s New Orleans jazz and it is a highly capable instrumental jazz performance that compliments Rainey's potent singing and story-telling ability. The horn players' use of dynamics is conspicuous; when Rainey sings, they play softly, and when she rests, they move to the forefront, a technique that highlights the call and response nature of the blues. She sings with emotion informed by the blues tradition,10 uses vibrato sparingly, and uses her voice to create a strong sense of swing.

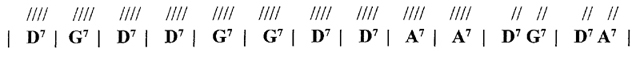

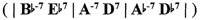

Rainey's composition incorporated some harmonic elements that would become staples of most jazz blues for the rest of the century. Of truly great importance is the use by blues composers of a major-minor 7th chord for the tonic. A great deal of popular music in the twentieth century was impacted by this innovation and also used this chord as the tonic.11 Another harmonic twist heard in the blues by this time was a brief shift to the IV7 (major-minor) chord in the second measure. This is what the resulting harmony looks like:

The lyrics to both "I Believe I'll Dust My Broom" and "Booze and Blues" are emblematic of the thematic material often heard in the blues. Lomax talks of "the melancholy dissatisfaction that weighed upon the hearts of the black people of the Mississippi Delta, the land where the blues began. Feelings of anomie and alienation, of orphaning and rootlessness—the sense of being a commodity rather than a person; the loss of love and of family and of place—this modern syndrome was the norm for the cotton farmers and the transient laborers of the Deep South a hundred years ago."12

* * *

In "Goin' to Chicago" (1941) by Count Basie and Jimmy Rushing, the harmony is virtually identical to Rainey's tune, and the AAB vocal form remains intact:

| A | Goin' to Chicago—Sorry that I can't take you | |

| A | Goin' to Chicago—Sorry that I can't take you | |

| B | There's nothin' in Chicago that a monkey woman can do | |

| A | When you see me comin', raise your window high | |

| A | When you see me comin', raise your window high | |

| B | When you see me passin' baby, hang your head and cry | |

| A | Hurry down sunshine, see what tomorrow brings | |

| A | Hurry down sunshine, see what tomorrow brings | |

| B | The sun went down, tomorrow brought us rain | |

| A | You're so mean and evil, you do things you ought not do | |

| A | You're so mean and evil, you do things you ought not do | |

| B | You've got my brand of honey, guess I'll have to put up with you |

The nearly identical harmonic and lyric schemes of the Rainey and Basie tunes contrast sharply with the widely differing approaches to accompaniment, arranging, instrumentation, improvisational styles, and rhythmic conception—an example of how the twelve-bar blues is able to facilitate diverse musical conceptions. On the Basie blues, Freddie Green's guitar, Walter Page's bass, and Jo Jones's drums all define the pulse while the four trumpets, three trombones, and five saxophones are manipulated by the arranger Buck Clayton to create a variety of timbral color. The blues form is also used to help create what Gunther Schuller calls the Basie band's "larger than life sound and projection."13 As opposed to "Booze and Blues" in which the horn players were able to improvise their responses to Rainey's singing, the arranger is now in control of the call and response aspect of the Basie blues.14

While almost all of the horn playing in Rainey's version is improvised, the horn solo in the Basie version is relegated to just two choruses before the singer enters. This blues solo highlights important trends that occurred in jazz in the 1930s and 40s. Instead of the improvised polyphony commonly heard in the 1920s, the trumpeter Buck Clayton improvises by himself over two choruses to create a highly personal statement.15 As for Rushing's performance, the first few notes he sings are bent blue notes similar to Rainey's, and there is a strong sense of rhythmic propulsion in his vocal delivery and a comparable use of vibrato.

* * *

When Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, and others developed bebop in the 1940s, the structure of the twelve-bar blues, while still evident, was partially obscured by a new type of jazz virtuosity. The use of a singer, something not always found in big band jazz, became even rarer in bebop; the stories were no longer told in the English language, but in the abstract language of instrumental jazz. Another change that helped mask the blues form was the extremely fast tempos at which the tunes were sometimes played.16

Parker's "Now's the Time," recorded in 1953, has become a well known jazz standard and was based on a form similar to the Rainey and Basie blues, but a few more harmonic twists had since been added. These include a iii-7-VI7-ii-7-V7 progression in mm. 8-10, and a new set of chords (the turnaround) is seen in the last two measures:

Despite the radical new melodic language that was heard over these chords, many important elements that helped to define Rainey's and Basie's blues are still intact:17

- an abstracted, instrumental version of the AAB form on the head

- the use of the twelve-bar form

- the use of a 7th chord for a I chord

- the use of a IV7 chord in the fifth measure

- the return to the I7 chord in the beginning of the eleventh measure

Parker's harmonic and melodic concepts have had an enormous influence on jazz composers since the early 1950s. Without delving into the music theory behind Parker's improvisation, it is still clear that Parker's solo on "Now's the Time" is melodically more complex than the previous examples we have examined in this paper. Yet despite Parker's complexity and virtuosity, the emotion of the blues that we heard in Rainey's, and Basie's music is unmistakably present.

The small group instrumentation on "Now's the Time," which consists of saxophone, piano, bass, and drums, sits in sharp contrast to Basie's big band and reflects a shift in emphasis from large group arrangements to the improvised solos. In his solo, Parker's ideas are clear, perfectly executed, varied, creative, and emotionally potent—some of the attributes from which Parker gained his status as one of the icons of jazz. The others in the group—Al Haig on piano, Percy Heath on bass, and Max Roach on drums—all do an adept job of framing Parker's solo and go on to take well-crafted solos themselves.

* * *

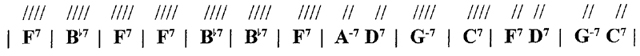

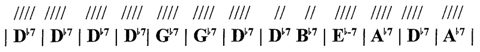

Perhaps the blues form was harmonically stretched the furthest from its origins by Parker's composition, "Blues for Alice," which exhibited major harmonic innovations. As heard in the 1951 recording, Parker changed the I chord from a major-minor 7th chord to a major-major 7th chord. Second, his masterful re-harmonization of the blues travels through seven key changes in its twelve bars. The new progression looks like this:

Despite these considerable harmonic changes and the fact that the AAB form of the head has now disappeared, Parker still retains the most essential elements from the standard jazz blues form:

- starting on a I chord (albeit a different type of 7th chord)

- the movement to the IV7 chord in the fifth bar

- the return to the I chord at the beginning of the eleventh bar

These three signposts of the blues are the anchors around which Parker weaves the remaining harmony. To bridge the harmonic distance between measures one and four, he uses a series of ii-7-V7 progressions  that descend in whole steps. To bridge the distance between measures six and nine, he employs a series of ii-7-V7 progressions

that descend in whole steps. To bridge the distance between measures six and nine, he employs a series of ii-7-V7 progressions  that descend chromatically. Even though the form of the blues is partially obscured by Parker's complex treatment of the harmony, a listener can still hear the twelve bar structure. As was the case with "Now's the Time," the head-solos-head arrangement emphasizes the improvised solos.

that descend chromatically. Even though the form of the blues is partially obscured by Parker's complex treatment of the harmony, a listener can still hear the twelve bar structure. As was the case with "Now's the Time," the head-solos-head arrangement emphasizes the improvised solos.

* * *

After Parker and the bebop practitioners had brought so much harmonic and melodic complexity to jazz, there was a trend later in the 1950s to bring the rhythmic attributes of the blues back to the forefront. Simpler blues riffs often replaced complex melodies as a way to create a stronger sense of rhythm in the heads. A great example of this more laid-back, groove-oriented approach is Horace Silver's hard-bop composition, "Doodlin'," which was recorded in 1954.

The harmony of "Doodlin'" once again resembles a standard jazz blues, the AAB form returns in the head, and Silver avoids the IV7 chord in the second measure, a choice that highlights his roots-oriented composition:

The tempo is relaxed and Silver's piano accompaniment is deeply informed by an authentic blues feel. Despite the similarity in the form to Rainey's blues, Basie's blues, and Parker's "Now's the Time," Silver's instrumental has a feel all its own. There's a coolness that contrasts with Parker's blues. It lacks the power of Basie's big band, yet it sets aside specific choruses for individual solos, as opposed to the group soloing heard in "Booze and Blues."

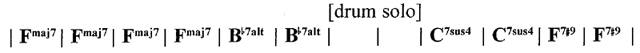

Silver takes the first solo in his signature laid-back, bluesy style. Hank Mobley takes the second solo on tenor saxophone and mixes in Parker-influenced lines. Kenny Dorham's trumpet solo follows, displaying a marked story-telling ability and a strong swing feel. Art Blakey takes a drum solo that displays some of his own recognizable musical vocabulary before the group returns to the head of the blues.

* * *

"Bird's Mother," a composition by pianist Jaki Byard which features Eric Dolphy, merges free jazz techniques with a twelve-bar blues that is similar in harmonic structure to Silver's "Doodlin'." The head to "Bird's Mother" sounds like a bebop blues, but Dolphy's unconventional instrument of choice (the bass clarinet) and Byard's jittery comping act as foreshadowing for an interpretation that pushes the form into new territory. During Booker Little's first chorus on trumpet, Dolphy disrupts the flow with some dissonant background figures while Byard adds some jagged chords. In his bass clarinet solo Dolphy fully demonstrates how the blues can support and merge with free jazz concepts. The first chorus of his solo has a singsong quality that is highlighted by his caustic note choices. As his solo progresses, he mixes in fast bebop lines with sharp-edged free jazz melodic concepts. Underneath Dolphy's solo, the rhythm section continues to delineate the blues's twelve-bar form but is much freer in interpreting the harmony when compared to Parker's, Silver's, or any of the other blues discussed in this article up to this point. As Dolphy's solo grows increasingly dissonant and playful, Ron Carter's bass lines becomes more angular, Byard's comping gets more skittish, and Roy Haynes's drumming gets busier without losing its sense of swing. Here is the harmony to "Bird's Mother" as heard on the head of the 1960 recording:

* * *

Chick Corea's approach to his jazz blues composition "Matrix," is as different from a standard jazz blues as was Parker's "Blues for Alice," but for different reasons. While Parker used the same chord progression each time through the form, Corea's solo quickly turns into a modal excursion, allowing for quick, subtle and unexpected shifts in harmonic color. It is a piece that hints at free jazz but never loses the twelve-bar form and always returns to F as a home tonality. The feel of the blues is partially lost due to the harmonic vagueness and fast tempo. The harmony on the head sounds something like this:

The members of the trio—Corea on piano, Miroslav Vitous on bass, and Roy Haynes on drums—work as a cohesive unit from the beginning of the track. Corea's solo lines have a unique contour to them, Haynes propels the group with his controlled chaos and Vitous's comparably less busy conception allows Corea and Haynes more flexibility during their improvisations. For Vitous's solo, Haynes and Corea lay out completely, allowing him plenty of space in which to maneuver. Corea and Haynes trade twelves, highlighting the twelve-bar form of the blues while stamping it with a musical vision far removed from early roots of the blues.

* * *

The Dave Holland Trio (Dave Holland on bass, Steve Coleman on alto saxophone, and Jack DeJohnette on drums) redirect the blues form with their 1988 rendition of Duke Ellington's "Take the Coltrane." The head to Ellington's tune uses standard jazz blues harmony and a four-bar phrase three times, creating an AAA form (as opposed to the more commonly heard AAB form). Despite the virtuosity of the musicians, there is a sense of playfulness that pervades the recording. Early in the saxophone solo, DeJohnette and Holland de-emphasize the beat while Coleman weaves in and out the fragmented pulse. This builds for three choruses creating a sense of release when DeJohnette and Holland break into a hard-swinging groove. All three players explore melodic and rhythmic avenues that are far removed from some of the earlier recordings discussed in this paper.

The serious playfulness of the group is fully revealed when Coleman and DeJohnette trade off. Instead of trading equal phrase lengths, Coleman takes eight measures, DeJohnette four, Coleman eight, DeJohnette four, etc. This odd configuration gets more uneven as they proceed. It is hard to tell if they keep the harmonic rhythm completely intact throughout this section, and that fact underlines the important issue here: the journey that started with a clearly delineated twelve-bar form has morphed into an exuberant romp with unpredictable results.

* * *

One trend in the jazz world within approximately the last twenty-five years is the reexamination of the music of older style periods. No matter how small the sub-genre of jazz, someone has figuratively or literally prefixed it with "neo" to reinvent or recreate it. The Dirty Dozen Brass Band is one of a number of New Orleans groups that has arisen and found its niche by reinventing the brass band—one of the genres that was influential in the formation of jazz in New Orleans early in the twentieth century. On the 1993 CD, The Dirty Dozen Brass Band Plays Jelly Roll Morton, the group pays tribute to an important early jazz composer and arranger. One cut on the CD, "New Orleans Blues," mixes a New Orleans second-line dance rhythm18 with a twelve-bar blues.

On "New Orleans Blues," Keith Anderson's sousaphone playing both outlines the blues form and helps create the second-line groove. After a four-bar introduction, the head appears and Efrem Towns on trumpet takes a solo informed by New Orleans performance practices.19 Before the tenor saxophone solo by Kevin Harris, the arranger Tom McDermott has inserted a four-bar section harmonized in fourths, harmonies that are more commonly associated with jazz styles of the 1960s and beyond than with the music of Jelly Roll Morton's time. Through their performance of "New Orleans Blues," The Dirty Dozen Brass Band reminds us that the blues, which arose out of hardship and pain, also became a medium to express celebration and transcendent joy.

* * *

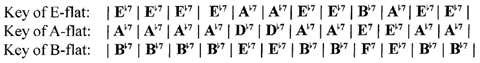

There are quite a few jazz arrangers who create complex sound sculptures that revel in their own density and intricacy. For over thirty years, Carla Bley has resisted that trend by composing and arranging deceptively complex music that is balanced with lucidity and a sardonic sense of humor. These characteristics are evident in her composition, "Blues in 12 Bars/Blues in 12 other Bars." But Bley also forces her sidemen to pay close attention to an arrangement that changes key, tempo, rhythmic feel, harmonic structure, and instrumentation, while occasionally interspersing contrasting non-blues sections into an opus that runs over fourteen minutes.

As heard on the CD that was recorded in 2000, the first chorus of Bley's blues is in the key of E-flat, the second chorus is in A-flat, and the third is in B-flat. This key scheme is a reflection of the I, IV, and V chords that were found in many of the blues examined in this study. In other words, Bley creates a matrix in which the I, IV, V progression of the blues is used on a larger scale to create a reflective key scheme:20

Bley uses this chord progression for the head of "Blues in 12 Bars/Blues in 12 other Bars" which uses sparse and humorous call and response riffs (a reference to earlier blues) between the bass, keyboards and horns. After the head, alto saxophonist Wolfgang Puschnig improvises over all thirty-six bars before an interlude leads to a trumpet solo by Lew Soloff. Bley creates more variety by remaining in E-flat for two choruses and then introducing a contrasting section for the last twelve bars of the trumpet solo.

Bley begins the second half of the piece by playing a slow gospel-influenced blues on piano. Steve Swallow, the bass player, takes a solo while Bley and the drummer Victor Lewis create interest with stop-time figures. For Larry Goldings's organ solo, the group shifts back and forth from an R&B/rock riff to a double-time feel before returning to the tempo and chord scheme that Bley had begun with thirteen minutes earlier. Although the blues still stands on its own as a vital musical form and vehicle of expression, in Bley's hands it has become artfully integrated into a much larger musical work.

* * *

This article illuminates how the blues form largely retained its identity while jazz artists from different periods used it as a foundation on which to build differing musical visions. Even as the instrumentation, harmonic and melodic languages, performance practices, and rhythmic feel of jazz evolved, there was always a high level of respect paid to the blues form. This respect has afforded the blues the ability to help shape the jazz language as jazz approaches its first century as an essential American art form.

References

Lomax, Alan. The Land Where the Blues Began. New York: Dell, 1993.

Oliver, Paul. The Blues Tradition. New York: Oak Publications, 1970.

Palmer, Robert. Deep Blues. New York: Viking Press, 1981.

Schuller, Gunther. Early Jazz. New York: Oxford University Press, 1968.

Wald, Elijah. Escaping the Delta. New York: HarperCollins, 2004.

Discography

Basie, Count. Count Basie—Ken Burns Jazz. Verve 314 549 090-2 (2000). Recorded in 1941.

Basie, Count. The Essential Count Basie, Volume 1. Columbia CK 40608 (1987). Recorded in 1939.

Bley, Carla. 4×4. Watt/30 012159 547-2 (2000).

Corea, Chick. Now He Sings, Now He Sobs. Blue Note 7243 5 38265 2 9 (2002). Recorded in 1968.

The Dirty Dozen Brass Band. The Dirty Dozen Brass Band Plays Jelly Roll Morton. Columbia CK 53214 (1993).

Dolphy, Eric. Far Cry. New Jazz 8270 (1960). Recorded in 1960.

Dave Holland Trio. Triplicate. ECM 1373 (1988).

Johnson, Robert. The Complete Recordings. Columbia/Legacy C2K 64916 (1990). Recorded in 1936.

Parker, Charlie. The Original Recordings of Charlie Parker. Verve 837 176-2 (1988). Recorded in 1951.

Parker, Charlie. Yardbird Suite—The Ultimate Charlie Parker Collection. Rhino R2 72260 (1997). Recorded in 1947.

Rainey, Ma. Ma Rainey's Black Bottom. Yazoo 1071 (1990). Recorded in 1924.

Silver, Horace. Horace Silver and the Jazz Messengers. Blue Note CDP 7 46140 2 (1987). Recorded in 1953.

1Lomax, Where the Blues Began, xiii.

2Ibid., xviii.

3With the exception of "Blues for Alice," all twelve recordings that I discuss reflect the chronological order in which they were recorded.

4Edison's invention occurred in 1877 and many of the precursors to the blues listed below date back to the 1840s.

5Palmer, Deep Blues, 26-27.

6Here, I am using the term "ragtime" in the way that Wald uses it on page 10 of Escaping the Delta, "as a catchall term for older African-American music."

7Wald, Escaping the Delta, 9.

8These lyrics were copied from the liner notes. (See the Robert Johnson CD in the discography.)

9The placement of the chords and slash notation in relation to the lyrics is approximated. On the recording, Johnson's phrases and the harmonic rhythm are, at times, considerably imprecise. This imprecision, which arose from a lack of "formal" musical training, renders a literal transcription problematic.

10My use of the term "blues tradition" is in line with Lomax's view when he discusses the "melancholy dissatisfaction . . . ." Lomax, Where the Blues Began, xiii. As the blues continued evolving throughout the twentieth-century, the form supported stories that conveyed a wide range of expressions including joy, humor, etc.

11Some early twentieth-century composers did occasionally use major-major 7th chords or minor-minor 7th chords for tonics. For example, Ravel's "Jeux d'eau" starts and ends on a major-major 7th chord and his "Une barque sur l'océan" begins on a minor-minor 7th chord. But composers in the European classical tradition shied away from the use of the major-minor 7th chords as tonic chords. Sometimes major-minor 7th chords were used non-functionally as in Debussy's use of chord planing techniques, but in functional harmony, major-minor 7th chords always maintained a dominant function. By the time twentieth-century composers such as Scriabin were using major-minor 7th chords to establish a "tonic" harmony, their functionality as tonics was clouded at best.

12Lomax, Where the Blues Began, xiii.

13Schuller, Early Jazz, 55.

14An earlier Basie/Rushing recording of "Goin' to Chicago" in which the instrumental responses to the vocals are improvised can be found on The Essential Count Basie, Volume 1 (see discography).

15There are plenty of examples of individual improvisers from the 1920s and group improvisation in the 1930s, but in general the trend moved from group improvisation in the 1920s to individual improvisation in the 1930s.

16A good example of this can be heard on a recording of "The Hymn," by Parker on Yardbird Suite (see discography). At tempos such as this (300 b.p.m.), the pianist's comping often gets sparser. As a result, the harmony is outlined primarily by the bassist and the soloists' improvised lines.

17During the second measure of "Now's the Time," the bassist stays on the I chord and the piano seems to imply the IV chord.

18The term "second line" originally referred to the crowd that followed a parade. (The parade itself was the first line; the crowd was the second.) The term has become synonymous with the rhythms played by the drummer and tuba player to which the crowd dances.

19Towns uses growls (flutter tonguing) and a liberal use of blues notes.

20In the ninth measure of the A-flat blues, Bley adds a  7 chord, not unlike an augmented sixth found in classical music.

7 chord, not unlike an augmented sixth found in classical music.