The Allure of Tango

Tango. The word alone conjures up alluring and exciting images associated with passion, sensuality, drama, gender archetypes, a national Argentine identity, a by-gone era, and an art form. The allure of tango has compelled both art-music composers to write stylized tangos and performers to play them. The late pianist and professor of music at The University of Buffalo, Yvar Mikhashoff (1941-1993), himself a tango aficionado, initiated the International Tango Collection in 1983, and the project culminated in a total of 126 short art-music tangos for solo piano by composers from over thirty countries.1 Since Mikhashoff specifically asked for them by name, I assert that these solo piano works are tangos, although they range in style from pieces that incorporate recognizable tango rhythms, melodic gestures, and phrase structure, to pieces that evoke memories of tango, to pieces with virtually no recognizable tango elements. The challenge for a performer is how effectively to project these stylized pieces as tangos.

A two-part analytical process that may help a musician to project a convincing interpretation of any stylized popular form should include: (1) familiarity with the form's original character; and (2) an understanding of how these characteristics are grafted onto or integrated into the stylized composition. Thus, in order to project a convincing performance of the stylized tangos in the Mikhashoff Collection, a pianist should ideally first understand the musical roots of tango and then in turn analyze these pieces in terms of the tango musical elements they contain. Furthermore, understanding the roots of tango may illuminate the interpretation of a contemporary composer's innovations in the tradition. In this article, I will discuss the two analytical steps crucial to a good performance of four tangos from the Mikhashoff Collection: Fromage Dangereux by William Schimmel (b. 1946), Tango No Tango by Jackson Hill (b. 1941), Tango Voices by William Duckworth (b. 1943), and Perpetual Tango by John Cage (1912-1992).2

What Makes It a Tango?

The first and fundamental question is: What are the stylistic features of tango music? In other words, how do you know a tango when you hear one? Of course, rhythm and meter are primal to this dance form. Early tangos from roughly 1900-1920 are in 2/4 meter, while later tangos from the 1920s-1940s were often in a slower 4/4. Two typical rhythmic features in tango include the habanera and the síncopa. The habanera, a classic Latin accompanimental rhythm of a dotted-eighth-16th note followed by two 8th notes, transferred to the early tango via an older Argentine folk-form called the milonga. I will hereafter refer to this pattern as the tango-milonga rhythm, and it is often syncopated with the 16th note of the first beat tied to the next 8th note. The síncopa is a distinct syncopated rhythm of 16th-8th-16th used in both tango melodies and accompaniment. To dissipate the syncopation, rhythm will often march along in steady 16th notes, punctuated by a marcato quarter-note accompaniment. Phrases classically divide into 4- and 8-bar groups, and harmonies tend to center around tonic, dominant and subdominant. With mostly lyrical and expressive melodies, distinct tango melodic gestures often include the linear 5-6-5 and triplet neighbor-note figures.

Examples 1 a, b, and c, illustrate the opening bars of three tangos para piano (tangos for piano) from the guardia vieja, or old-guard period of tango, around 1910: El Choclo by Angel Villoldo (1861-1919), El Marne by Eduardo Arolas (1892-1924), and Ojos Negros by Vicente Greco (1888-1924), where we can observe some of the classic rhythmic, metric, melodic, and phrase-structure elements that define tango. Although they portray a stereotypical reduction of the tangos played by the orquesta típicas in Argentina that classically included bandoneóns, violins, bass, maybe a guitar, and piano, these simple tango renditions published in the teens and 20s were often (and still are) the only printed tango music available for foreigners.

Example 1. Tangos para piano from the guardia vieja.

a. El Choclo by Angel Villoldo

b. El Marne by Eduardo Arolas

c. Ojos Negros by Vicente Greco

The basic texture in all three excerpts is a simple melody and accompaniment, where the left hand plays the bass line and chords in the tango-milonga rhythm, and the right hand plays mostly a single-line melody. The meter is 2/4, and the phrases mostly fall into 4- and 8-bar groups (Ojos Negros has a beautiful and more complex structure, where the first two phrases divide three bars). While the tango-milonga rhythm persists in the accompaniment of all three examples, the equally important rhythmic element of the síncopa is found in both El Marne, mm. 1,2, and 4 and Ojos Negros, mm. 2 and 6. A triplet neighbor-note figure, another important melodic and rhythmic element in tango, is found in El Choclo, as well as a steady stream of 16th notes. Although these examples only illustrate the opening phrases of each excerpt, I should add that their complete formal structures illustrate the typical tango form of closed 3-part structures with a Trio in the parallel major.

Many tango lyrics describe tragic and dramatic life situations, such as the plight of an immigrant's life or, more often, lost or betrayed love. Many tangos are in minor keys, and fittingly the classic lament figure of the linear 5-6-5 is embedded in many tango melodies. Note how all three tango excerpts in Example 1 in are in minor keys, and they all incorporate the linear 5-6-5 figure.

Tango Elements in the Stylized Tangos of the International Tango Collection

We may now turn to the pieces from the International Tango Collection, with an analytical eye for how they may incorporate tango elements, and/or fuse them with more contemporary musical styles and gestures.

Fromage Dangereux (1985) by William Schimmel

One of the foremost accordionists in the world, William Schimmel, has been a key figure in the tango revival in North America over the past 20 years. He co-founded the Tango Project in 1982 in New York City, a trio of accordion, violin, and piano, which performed the music for the tango scene in the film Scent of a Woman (directed by Martin Brest, 1992) and has produced four CDs to date of traditional tangos and tango hybrids. The first eight measures of his contribution to the International Tango Collection is shown in Example 2.

Example 2. Fromage Dangereux by William Schimmel, page 1. Used by the permission of the composer.

Fromage Dangereux is modeled on a tango para piano with its typical melody and accompaniment texture and its persistent tango-milonga rhythm in the accompaniment. Other classic tango features include the 2/4 meter, the lament 5-6-5 figure in the opening, and the síncopa in m. 3. Phrases fall into typical 4 + 4 making larger 8-bar groups, and the harmony centers on tonic, dominant, and subdominant areas. The Trio, not shown here, is in the key of C major. Only a few improvised melodic flourishes suggest that this piece was written by a contemporary composer.

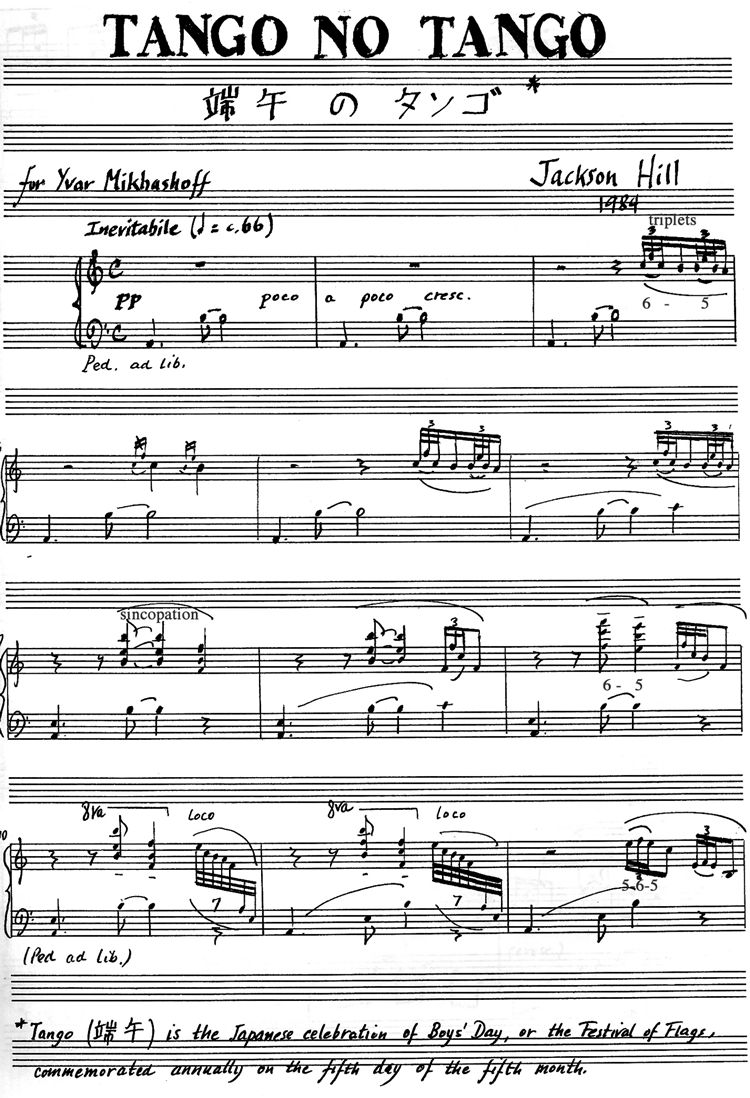

Tango No Tango (1984) by Jackson Hill

American composer and musicologist Jackson Hill has taught at Bucknell University in Lewisburg, Pennsylvania since 1968. One of his primary compositional influences is traditional Japanese music, and he projects his Asian aesthetic in his Tango No Tango. Note the composer explains the double meaning of the title at the bottom of p. 1 of the score: Tango is the Japanese celebration of Boys' Day, or the Festival of Flags, commemorated annually on the fifth day of the fifth month." (See Example 3.)

Example 3. Tango No Tango by Jackson Hill, page 1 of the score with annotations. Used by the permission of the composer.

The static harmony and absence of rhythmic drive create a tranquil atmosphere, making this piece more of a "no tango" than a tango. Yet, Hill makes distinct references to tango music, and they can be accentuated in performance. The opening syncopated rhythm in the bass, which continues through most of the piece, hints at the typical tango-milonga rhythm in augmentation. Although the quick melodic flourishes seem to evoke a Japanese flute more than a tango melody, the triplet idea is drawn from the typical tango melodic embellishment, heard in El Choclo (Ex. 1a). Also, the linear 6-5, the classic "lament" figure, lies behind these triplet flourishes as the F-E over the A pedal in the bass. The harmony is distinctly not tango, and its atmosphere evokes a Zen temple more than a tango dance hall. Using the minor pentatonic mode as a pitch resource, Hill carefully avoids the pitch D in the first fourteen bars until the sustained A minor harmony finally moves to D minor in m. 15. The harmony shifts throughout between A minor and D minor, tonic and subdominant, and the composer intentionally avoids the note G altogether to create his distinctive modal atmosphere. The phrase structure and form of Hill's piece also illustrate the "no tango" aspect of the title. Unlike Schimmel's tango, which adheres to the traditional 4+4 phrase groupings and a distinct three-part structure, Hill's tango is an organic one-part form with phrases that flow seamlessly from gesture to gesture over a static harmony.

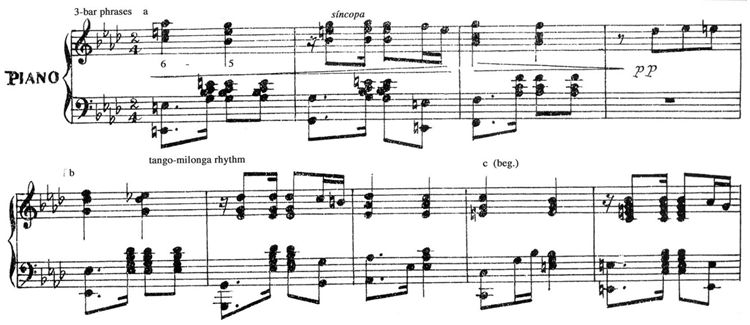

Tango Voices (1984) by William Duckworth

A contemporary and colleague of Jackson Hill at Bucknell University, William Duckworth contributed a piece to the Mikhashoff Collection even further removed from traditional tango than Hill's Tango No Tango. Yet, through the title Tango Voices, it's syncopated rhythms, and the anacrusis 5-6-5 melodic motion (G-A-G over the pedal C) that initiates the opening phrases (marked a and b in the score; see Example 4), a pianist could project the composer's evocation of a tango memory. Certainly the rise and fall of the phrase waves, coupled with the rhythmic syncopation, give this piece a breathless exuberance. Duckworth's irregular phrase structure, minimalist compositional style, and modal harmonic language remove this piece from traditional tango music. Yet, as noted in concert programs in the Mikhashoff Archives, Mikhashoff liked Duckworth's Tango Voices so much that after he premiered it in Oslo, Norway on Aug. 19, 1984, he performed it in Toronto and Tokyo in 1984; in London and Buffalo; for a Dance Theatre Workshop in New York City in 1986; and in Warsaw, Poland in 1988.

Example 4. Tango Voices (MSS 52) ©1984 by William Duckworth, p. 1 of the score with annotations. Used by permission of Monroe Street Music, Box 4006, Park Avenue Station, West New York, NJ 07093. All rights reserved.

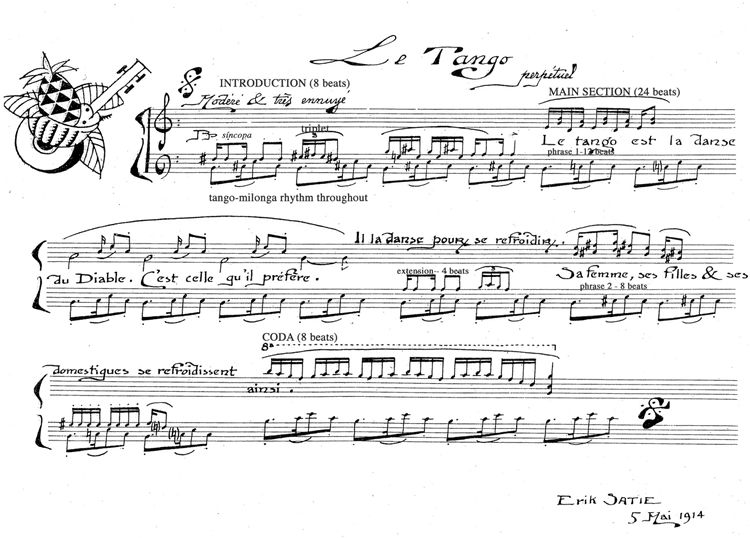

Perpetual Tango (1984) by John Cage

Finally, I will consider Perpetual Tango by John Cage. Although it presents the player with a mystery and a game, it also incorporates some basic tango elements that a performer should be aware of. Cage's contribution to the Mikhashoff collection is actually a re-working of Erik Satie's Le Tango pertétuel, dated May 5, 1914, the height of the tango craze in Paris, from his collection Sports et Divertissements, a set of twenty witty and imaginative miniature character pieces. Cage initialed his score, dated it 2/17/84, and added "seventy years after." Like Satie, Cage inscribed a text in his manuscript about tango, and in fact his text paraphrases the older composer's description of tango as a dance of the devil. Following is a comparison of the two:

Example 5. Le Tango Perpétuel by Erik Satie.

Text by Satie and Translation

Le tango est la danse du Diable. C'est celle qu'il préfère. Il la danse pour se refroidir. Sa femme, ses filles & ses servants refroidissent ainsi.

The tango is the dance of the Devil. It is the one he prefers. He dances it to cool himself off. His wife, daughters, and servants also cool themselves off.

Text by Cage

ThE Devil neveR takes tIme to thinK he juSt tAngos insTead he Is quitE cool hE his daughteRs wIfe and servants Know they'll never Stop dAncing They never do It's vEry hot

In case there is any doubt his tango is a reworking of Satie's, Cage capitalizes the letters that spell out "Erik Satie" twice in the two lines of his text.

Since Cage's tango shadows Satie's in form, phrase structure, rhythm, and even pitch material, let us first take a look at the French composer's miniature score.

Although Satie avoids a time signature and bar-lines in his score, an underlying 2/4 meter is evident based on the barring of notes, and phrases fall into classic multiples of 2, 4, and 8-beat groups. I read the structure as follows:

8-beat Introduction, establishing a simple two-voiced texture, two-beat metric groupings, incessant left-hand accompaniment in the tango-milonga rhythm, and tango rhythmic patterns of the sncopa, 16th-note triplet followed by an 8th note, and steady 16th notes in the right-hand

24-beat Main Section, divided into 2 phrases, where Satie underlays his text

Phrase 1: 12 beats (Le tango est la danse du Diable. C'est celle qu'il préfère.) + 4-beat extension (Il la danse pour se refroidir.), making a larger 16-beat group

Phrase 2: 8 beats (Sa femme, ses filles & ses domestiques se refroidissent ainsi.)8-beat Coda, shift into upper register

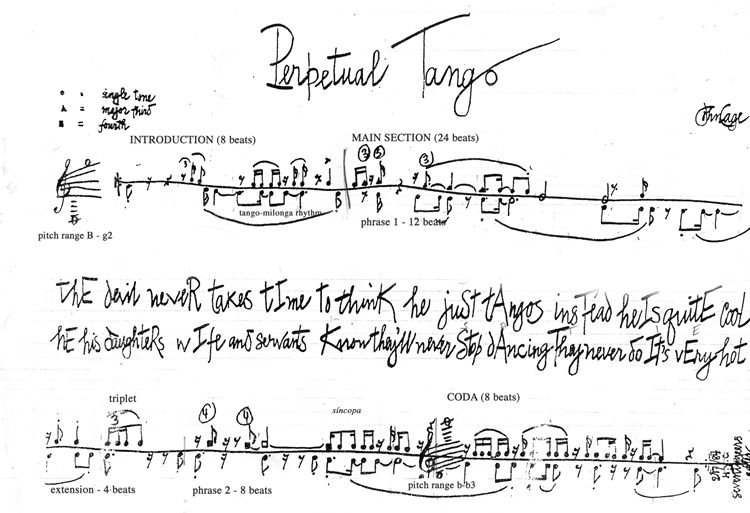

Now let us turn to Cage's Perpetual Tango (see Example 6, Cage's score with analytical markings). Like Satie, Cage omits a time signature and bar lines. He maintains Satie's basic two-voiced texture in the right-hand and left-hand, but only notates the rhythms, articulations, and phrases above and below a single line.

Example 6. Perpetual Tango by John Cage. ©1984 Henmar Press Inc. sole selling agent C.F. Peters Corp. All rights reserved. Used by permission.

Although the rhythmic groupings are not as obvious as Satie's with beams, Cage, in fact, maps out Satie's underlying structure in his tango of an eight-beat introduction, a twenty-four-beat main section, and an eight-beat coda. To illustrate, I have added broken and solid bar lines to indicate phrases and sections in the score in Example 6. Thus, the form follows Satie's:

8-beat Introduction

24-beat Main Section, subdivided into two phrases of

1) 12 beats + 4-beat of extension and

2) 8 beats8-beat Coda, shift into upper register

Cage transfers many pitch and rhythmic events from Satie's tango to his Perpetual Tango. Although specific pitches in Cage's tango are "indeterminate" and various note-head shapes indicate whether to play a single pitch (round), a major triad (triangle), or the interval of a 4th (square), the composer twice indicates the range from which to choose notes. Cages's first indicated range of notes, B - g2, defines Satie's lowest and highest notes in the Introduction and two main phrases in beats 1-32; the second indicated range, b - b3, coincides with Satie's shift in pitch register for the "coda." What's more, Cages's indications to play triads and 4ths coincide exactly with Satie's use of the same harmonic structures in the main section: the triads in the first phrase and the 4ths in the second. Also, Cage's half-notes coincide with Satie's inner-voice descending line A-G-F in half-notes in the first phrase of the main section.

While Cage does not use specific tango references in terms of pitch, he shadows many of Satie's tango rhythms, including the tango-milonga pattern, the síncopa, and steady 16th notes. Furthermore, Cage places his only use of the 16th-note triplet - 8th note figure in the first "measure" of the second line exactly where Satie did, perhaps signifying a point of closure or formal segmentation cue in both Satie and Cage.3

Conclusion

Pieces in Yvar Mikhashoff's International Tango Collection range in musical language from tonal to atonal to neotonal, and in compositional style from popular to minimalistic to aleatoric. Some, in fact, resemble stylized tango caricatures from the tango craze of the 1910s, either the gentrified tango music that landed in Paris around 1912, which Satie surely heard in 1914 and transferred to Cage, or the simplified tangos para piano published in Argentina, which must have been a source for Schimmel and other more traditional composers represented in the Collection. All of these pieces, however, bear the title of "tango," and a convincing performance should project those metric, rhythmic, melodic, and phrase-structure elements that distinctly make them one.

Endnotes

1The Yvar Mikhashoff Collection of Tangos, 1983-1991, Mus. Arc. 1.10 is housed in the Music Library at the University at Buffalo. I am grateful to music librarians John Bewley and Amy Ward for their help navigating through the Archives in March 2005. The URL to the finding aid is

2All four of these pieces are included in Mikhashoff's recording Incitation to Desire NA073CD New Albion, 1995.

3Thanks to Robert Hatten for this observation.