One model of the relation between analysis and performance asserts that analysis, because it is a rational endeavor, is in a position to preside over performance—to determine how it should be—because performance is by nature more intuitive and emotive. In this model, a performance must rely upon, and defer to, the preexisting notions of an analysis in order to arrive at a valid structural interpretation of a work.1 Theorists have grown increasingly resistant to this hegemonic model, sometimes retorting that a performer can arrive intuitively at a compelling reading of a piece's structure, and thus that performance can influence analytical understanding as much as the reverse. In this view, performance and analysis stand in a symmetrical relationship relative to the work, each capable of realizing its potentialities and of offering equally valid interpretations.2

I believe this to be true, but would like to suggest another way to deconstruct the problematic dichotomy asserted by the first model. This is to demonstrate that analysis, far from consisting solely of abstract claims that must somehow be instantiated in performance, has itself sensuous and emotive aspects or connotations. In this view, analysis stands on common ground with performance and is naturally oriented toward it. When analysis is viewed in this way, proceeding from analysis to interpretation is no longer problematic, as the performance is no longer expected to assimilate something foreign to it, i.e., abstract concepts, but merely to draw from a well of sensuous and emotive experience common to analysis and performance alike. Moreover, I believe advantages accrue to the performer from following an independent analysis (especially if he undertakes it himself). Attaining insight into non-obvious structural relationships is often difficult to achieve at the instrument and often requires separate analytical activity.

I believe Schenkerian analysis is particularly suited to this alternative model. For one thing, many of its constructs are somatic in orientation; for another, these somatic aspects often have distinct emotive connotations. It is due precisely to these physical and emotive features of Schenkerian analysis, features in which performance is also patently grounded, that Schenkerian analysis is inherently compatible with and naturally applicable to performance. I shall elaborate this assertion in this paper, first by considering the metaphorical nature of Schenkerian analysis generally and by outlining particular analytic metaphors within this system that are of potential relevance to performance. Then, I shall analyze the theme from the first movement of Mozart's Piano Sonata in A major, K. 331 and the first section of Chopin's Nocturne in C Minor, op. 48, no. 1, in each case discussing performance implications that arise from the analysis.

Schenkerian Analysis as Metaphor

Susanne Langer identifies two basic kinds of symbols. Discursive, or linguistic, symbols refer to the rational order of experience due to their linear syntax and denotative capacity. Presentational symbols, on the other hand, such as artworks, because of their multi-dimensionality and ability to present simultaneities, can symbolize extremely subtle and complex mental and emotional states that language cannot capture.3 Music, in her view, is a presentational symbol. In its rhythmic motion, patterns of tension and release, hierarchical complexity, etc., music is a logical analogy for feelings and other inner states.4 In other words, music and other art forms do not refer to dimensions of internal experience but present and embody them.

Can the same be said for systems of music analysis? In particular, does a Schenkerian analysis function primarily discursively, as an assertion of propositional fact, or presentationally, as an artistic embodiment of human states (in a manner analogous to the music itself)? In other words, is it better understood rationally or experientially? Certainly, components of a graphic analysis are often read for the information they convey; for example, an Ursatz can be read as the musical equivalent to the proposition "this piece is governed by a fifth progression," or, "this piece embellishes a fifth progression in successive stages of diminution," etc. But could one postulate that the Ursatz and other Schenkerian constructs also embody tangibly physical and expressive qualities, or more precisely, embody the potential for the materialization of such qualities in performance?5 I believe one can, but before arguing for this directly, I would first like to consider, for the sake of comparison, two ways in which Schenkerian analysis is often treated discursively and literally, rather than presentationally and metaphorically, at least when such analysis is considered in the context of performance.

A study by Cynthia Folio exemplifies the first trend.6 She aims to give a practical account of how analysis can be applied to performance, utilizing the first movement of Bach's Sonata in E Major for flute and harpsichord as her central example. Some of the pervasive features of this piece that she derives from structural analysis are parallel tenths governing relatively long stretches of music, embedded double neighbor motives, and motivic connections between flute and harpsichord. Her main advice to performers is to emphasize or "bring out" (dynamically or agogically) the notes that comprise these underlying lines and motives, and to highlight long-range structural and registral connections by dynamically "matching" the notes that comprise such connections.7 In this account, the analysis itself, while not overtly reductive in orientation, ultimately betrays such an orientation by using performance to cut through foreground phenomena in order to project structural lines. This reductive methodology, in turn, equates with a discursive, or propositional one; that is, it is tantamount to stating a supposed fact, i.e., that a structural entity exists, rather than, in a presentational manner, pointing to the qualities the entity possesses. Folio thus employs the conjunction of analysis and performance discursively: the foreground, via performance, is reduced to structural fact.

Another literalist application of Schenkerian principles to performance involves rendering "long lines" as supposedly implied by the Urlinie (and perhaps Zug as well). To be sure, the Urlinie and Zug relate mostly non-contiguous pitches, exposing a musical logic that is operative over extended time spans. Yet, proponents of this approach misconstrue this metaphorical notion of aural or conceptual connection as implying or entailing literal (i.e., physical) connection, that is, as a mandate to create a "long line."8 In other words, the musical unity that Schenkerian constructs potentially expose is often misconstrued by performers as uniformity of articulation (and frequently of tempo as well).9

Certainly, it is sometimes appropriate and desirable to project structural tones or create long, legato lines. Yet, the fundamental shortcoming of these literalist approaches is that they are not conducive to manifesting the quality of organic coherence that Schenkerian constructs were intended to expose. That is, simply demarcating or connecting structural pitches by itself does nothing to ensure or create meaningful relationships among these pitches. This can only be achieved by the strategic and insightful use of articulation, dynamics, and tempo gradations—the performer's essential resources. More crucially, the particular pitches that comprise the Urlinie and Zug are hardly the point; rather, their significance derives from their interaction with the surface, from their function as a backdrop in relation to which foreground particularities are expressively salient.10 In brief, these discursive/literalist strategies simply do not go far enough; by focusing on the supposed fact, the mere existence, of structural lines, they limit the creative uses to which such constructs can be put.

Some attributes of a presentational alternative should already be clear from the preceding discussion. Such an approach would view a structural progression not as a musical fact—as actual pitches to which surface details are reduced11 and which need to be projected and connected in performance—but as a metaphorical construct that can be applied to, interact with, and illuminate the music. Nicholas Cook, for example, argues that Schenkerian analysis offers not an objective presentation of musical structure, but rather a metaphor of Fuxian counterpoint in terms of which we are supposed to perceive the music.12 In other words, through a Schenkerian filter, we listen to a piece as if it were a prolongation of the prototypes of species counterpoint.13 The point is not to state an objective fact about the piece, e.g., "it elaborates this contrapuntal configuration," but rather to ask, "what would it be like to hear the piece as an elaboration of this contrapuntal configuration—what particular details come to light at a result?" Analysis, in this view, is not primarily an assertion of fact but rather a catalyst for imaginative perception.14

Moreover, viewing an analytical system as a metaphorical, rather than explanatory, apparatus adjoined to the music ("hear the music as if . . . ") ensures a continual engagement with the musical surface, with the particular ways in which the foreground manifests, embellishes, and deviates from contrapuntal prototypes and underlying structural lines. In this scenario, analysis sustains immediacy by using, in Pieter Van Den Toorn's words, "the general as a foil for the sensed particular."15 I contend that the most fruitful ramifications of Schenkerian structure for performance involve precisely these particular interactions between foreground and deeper levels, for it is these interactions, rather than structural entities per se, that are laden with the somatic and expressive connotations that can be readily actualized in performance. In other words, what is most applicable to performance are not the tones of the Urlinie or Zug themselves, but the expressive details that emerge from understanding or hearing the musical surface in relation to these longer lines.

I hope to have established at this point the essentially metaphorical nature of Schenkerian analysis, or at least the considerable advantages of thinking of and using Schenkerian analysis in a metaphorical fashion. Now let us recall some concepts and tools within the system whose metaphorical nature is well established. On a broad level, the notion of structural levels employs a spatial metaphor, whereby mostly non-contiguous pitches are collected into various spaces (conceptual categories and physical spaces on the page) indicative of their structural significance;16 also, the concept of voice-leading is at once spatial and somatic, involving the motion of an entity through tonal space toward a goal.17 Other metaphors are less central to the system, but perhaps even more immediately applicable to performance; these include unfolding, registral transfer, reaching over, and motivic processes such as expansion and compression (these last two, while perhaps not properly Schenkerian concepts, often arise from Schenkerian readings). All of these rely upon the metaphor of musical space and of an agent physically engaging such space in various ways. In light of how abundant physical metaphors are in Schenker's system, and of the patently physical nature of performance, the body is an obvious point of contact between Schenkerian analysis and performance. I shall demonstrate that one can readily apply analytical insights to performance by actualizing, in sound and time, the spatial/somatic metaphors that underlie and are connoted by Schenkerian constructs.

Hence, my methodology in the forthcoming analyses will be to uncover the interactions between surface and structure, consider their physical and expressive dimensions, and then outline ways in which these dimensions can be exploited in performance. For the Mozart, I shall focus only on spatial-somatic metaphors. For the Chopin, I shall focus more on the emotive connotations of such metaphors. Also, whereas in the Mozart I shall focus on more or less isolated states, in the Chopin I shall extend my methodology by interrelating these states, in other words, by suggesting a musical narrative, from which will emerge higher-level, more complex affective states that can be embodied in performance.

A Reading of Mozart, K. 331 (Theme)

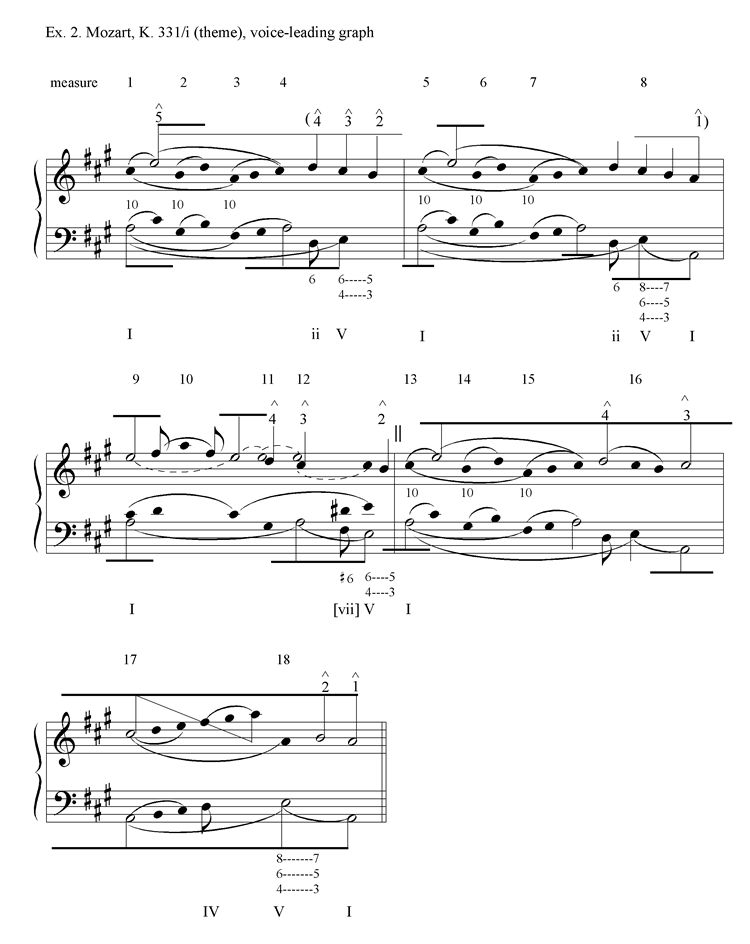

Ex. 2 provides a voice-leading graph of the theme, shown in Ex. 1. In mm. 1-4, each tone of the 3Zug is approached from a third below; the last tone, C-sharp, is delayed because its approaching third is filled in by step. One senses here an expansive quality: that an inevitable pitch (C-sharp) is being deferred, and that more time is needed in order to accommodate more linear detail.18 Conversely, m. 4 compresses the structural tones  -

- -

- into a smaller space; that is, they occur within a much shorter time span (1 1/3 beats) than that in which

into a smaller space; that is, they occur within a much shorter time span (1 1/3 beats) than that in which  unfolds (6 2/3 beats). (This structural acceleration toward the end of a phrase is, of course, prototypical.)19 M. 7, like m. 3, fills in the third motive, but unlike m. 3, it does so within the established time frame of 1 1/3 beats (as in mm. 1 and 2); it is thus an acceleration relative to m. 3 (this acceleration is needed in order to reach an authentic cadence by the next bar). M. 9 is thematically analogous to m. 1, but whereas m. 1 states both a neighbor (Nb.) and a third motion, m. 9 defers the third motion (which is compressed into the grace notes leading into m. 10), and thus has an expansive quality. Conversely, the third motion that is excluded from m. 9 is then fit into the grace notes leading into m. 10. Finally, in m. 17, C-sharp (

unfolds (6 2/3 beats). (This structural acceleration toward the end of a phrase is, of course, prototypical.)19 M. 7, like m. 3, fills in the third motive, but unlike m. 3, it does so within the established time frame of 1 1/3 beats (as in mm. 1 and 2); it is thus an acceleration relative to m. 3 (this acceleration is needed in order to reach an authentic cadence by the next bar). M. 9 is thematically analogous to m. 1, but whereas m. 1 states both a neighbor (Nb.) and a third motion, m. 9 defers the third motion (which is compressed into the grace notes leading into m. 10), and thus has an expansive quality. Conversely, the third motion that is excluded from m. 9 is then fit into the grace notes leading into m. 10. Finally, in m. 17, C-sharp ( of the primary line) is unfolded by an expansion of the ascending linear third motive to a sixth; this is a more gradual and purposeful ascent to the A5 that was reached so casually in m. 10.

of the primary line) is unfolded by an expansion of the ascending linear third motive to a sixth; this is a more gradual and purposeful ascent to the A5 that was reached so casually in m. 10.

A couple of foreground details project the underlying temporality as implicit in the motivic processes just described. First, notice the sixteenth notes in m. 4 that result from the E appoggiatura attached to the  -

- -

- descent. This E, in turn, creates not merely rhythmic acceleration, but also motivic compression; that is, it creates a surface parallelism of the

descent. This E, in turn, creates not merely rhythmic acceleration, but also motivic compression; that is, it creates a surface parallelism of the  -

- -

- -

- of mm. 1-4, compressing it into a mere 1 1/3 beats (see bracket in Ex. 1). Hence, in terms of both foreground rhythm and motivic parallelism, m. 4 truly expresses and emphasizes the structural acceleration that underlies it. Likewise, the expansive motivic process in mm. 3-4, i.e., the filling in of the third space, is rendered easily audible on the surface by a repetition of the y motive (see Ex. 1), which creates a broader, slower effect relative to the previous two measures.

of mm. 1-4, compressing it into a mere 1 1/3 beats (see bracket in Ex. 1). Hence, in terms of both foreground rhythm and motivic parallelism, m. 4 truly expresses and emphasizes the structural acceleration that underlies it. Likewise, the expansive motivic process in mm. 3-4, i.e., the filling in of the third space, is rendered easily audible on the surface by a repetition of the y motive (see Ex. 1), which creates a broader, slower effect relative to the previous two measures.

In these couple of cases, then, Mozart's foreground rhythmic processes actualize the temporal implications of the underlying voice-leading and motivic processes. The acceleration implied by the structural unfolding in m. 4 is instantiated on the foreground by quicker rhythms (and a compressed parallelism), while the sense of elongation implied by the linearization of the third is instantiated by slower rhythms. Put another way, structural properties here are exemplified on the foreground.20 Generally, such exemplifications occur quite often, in the guises of foreground rhythm and motivic parallelism, which provide perceptual windows into the structural underpinning of a phrase, section, or entire piece. Not all structural phenomena, of course, receive surface exemplification; music often thrives on a disparity between the foreground and deeper levels. When such exemplification does occur, however, it may serve as a convenient cue to the performer to materialize a structural quality. Where a performer takes this cue, her exemplification of structure may be seen as an extension of that which already occurs on, or is implied by, the foreground. In this respect, structure, foreground, and performance can be seen as components of a single, indivisible process—links on a chain.

Thus, for example, the performer can manifest the underlying motivic expansion in mm. 3-41 by playing the broader rhythms even more broadly, at a slightly slower tempo than the preceding bars. Likewise, he can manifest the structural acceleration in m. 4 with a slight acceleration that conveys the impression of having to fit more notes into less space; here, the subtle tempo fluctuation will intensify the inbuilt rhythmic thrust, which in turn exemplifies the underlying structural acceleration. Furthermore, one can accelerate m. 7 in relation to m. 3, for the reason cited above. One may also differentiate the sforzando in m. 4 from that in m. 8. The first sforzando signals compression, and thus has the connotation of being sharp and abrupt, an effect that can be easily conveyed with a sharp tone and quick attack. The second is quite the opposite, signaling being comfortably in place, more than ready for the awaited resolution; this can be conveyed with a slower attack and less pronounced forte.21 In m. 10, the grace notes can be played with tonal substance to convey their motivic import, and at the same time very hurriedly to convey the sense that they are trying, almost futilely, to fit in the third motive by the next downbeat. One can also exemplify the phrase expansion in mm. 16-17 by playing more expansively, or broadly, and connecting those two measures in order to suggest a longer phrase.22 The motivic extension itself in m. 18 necessitates a sense of building, of going beyond the third space; such a crescendo and slight ritardando arriving upon the A5 will be especially intense by virtue of working against (to borrow a term from Narmour) the "counter-cumulative" rhythm.

This example demonstrates how conducive spatial/somatic analytical constructs are to realization in performance. While a performance cannot be expected to convey propositions about structure that perceivers will be consciously aware of, it can express the visceral qualities associated with structural processes; it is the somatic qualities that underlie analysis, rather than the more recondite claims of analysis, that the performer can express and the perceiver experience. Hence, while the average perceiver will not likely be conscious of motivic expansions and compressions per se, he will, in listening to a performance following the above guidelines, grasp on some level their sensuous effect. In this respect, uncovering structural entities is the starting rather than ending point, a point of departure from which to develop a succession of tangible qualities. Indeed, most or all analytical assertions have the capacity to be absorbed by, or assimilated to, the purely perceptible medium of sound and time.23

Objections

A few possible objections must be answered at this point. One is that the rhythmic features I cite (that enact or exemplify motivic manipulations) are objectively present or "built into" the music and thus need not be emphasized in performance. One might argue, for example, that in mm. 3-41, the delay of C sharp and the motivic expansion are evident in the rhythmic broadness, so one need not broaden the tempo further to render the motivic expansion evident. Likewise, in m. 4, the structural acceleration is exemplified by the sixteenth notes, so one need not additionally accelerate. I would rebut that the somatic dimension of analysis is primarily qualitative, not quantitative, and that rhythms as played exactly, or metronomically, cannot by themselves convey somatic qualities. For example, in mm. 3-41 the tangible quality of delay and expansion, and the associated one of tension, can only be expressed by subtle and almost unquantifiable tempo and dynamic manipulations; a mechanistic rendering will express mere plodding, not these qualities. Likewise, the sixteenth notes in m. 4 by themselves, i.e., played metronomically, will express speed, but not the quality of hurriedness or compression that is implied here. In short, spatial/somatic qualities are never objectively present in rhythms per se, but must be expressed by the subtle rhythmic and dynamic variances of a performer.

A related objection might be that the tempo fluctuations I recommend are not explicitly indicated by the composer; while musicians generally accept tempo rubato when applied to works of the romantic period, many are skeptical when it is applied too liberally to works of the classical period. While in the classical period uniform tempo was indeed the norm, treatises and other writings of the period paint a picture of a much more flexible "uniformity" than that embraced by performers of today; Turk and C. P. E. Bach, for example, acknowledge numerous instances where tempo deviations (notated and non-notated) are called for.24 More importantly, however, I would argue that such historical justification is scarcely needed in this context, for if we sanction (and we generally do) the anachronistic application of Schenkerian analysis to works of this period—to which many of Schenker's aesthetic precepts are completely foreign—we should also sanction a mode of performance which, as I am arguing, follows from that type of analysis.

A final objection might be that the guidelines I advocate (as in the above example) are too broad to have any precise or predictable impact upon performance; this I concede. Indeed, the metaphorical qualities I discuss are quite broad and are not susceptible to quantification. Consequently, the ways in which they may be expressed will also encompass a broad range of tempo and dynamic fluctuation whose limit will be determined more by artistic taste and viability than by correctness. In other words, if we value an analytic insight not for its fixed, propositional content, but rather for its imaginative potential, we must also grant a wide array of realizations of such potential (conversely, those who conceive of an analytic insight as propositional often prescribe a fixed way of playing, of realizing that insight). Yet, I view such flexibility as desirable because it is within this wide range afforded to performers that many colorful and creative things happen—qualities and relations that express but also invariably exceed their analytic impetus. A corollary of this position is that, since there is no singular thing a performer must do to instantiate an analytic insight, I see little need to measure precisely a performer's tempo fluctuations—a fashionable methodology in current performance studies—since that tells us little about the sensuous qualities expressed by a performance (analytically derived or not). In short, the ways in which analysis can be appropriated by a performer can be neither exhaustively prescribed nor precisely represented after the fact. Indeed, even as I attempt to locate common ground between analysis and performance, I must also concede an inevitable gap between them; no one-to-one correlation exists between the two domains.

A Reading of Chopin, Nocturne, op. 48, no. 1

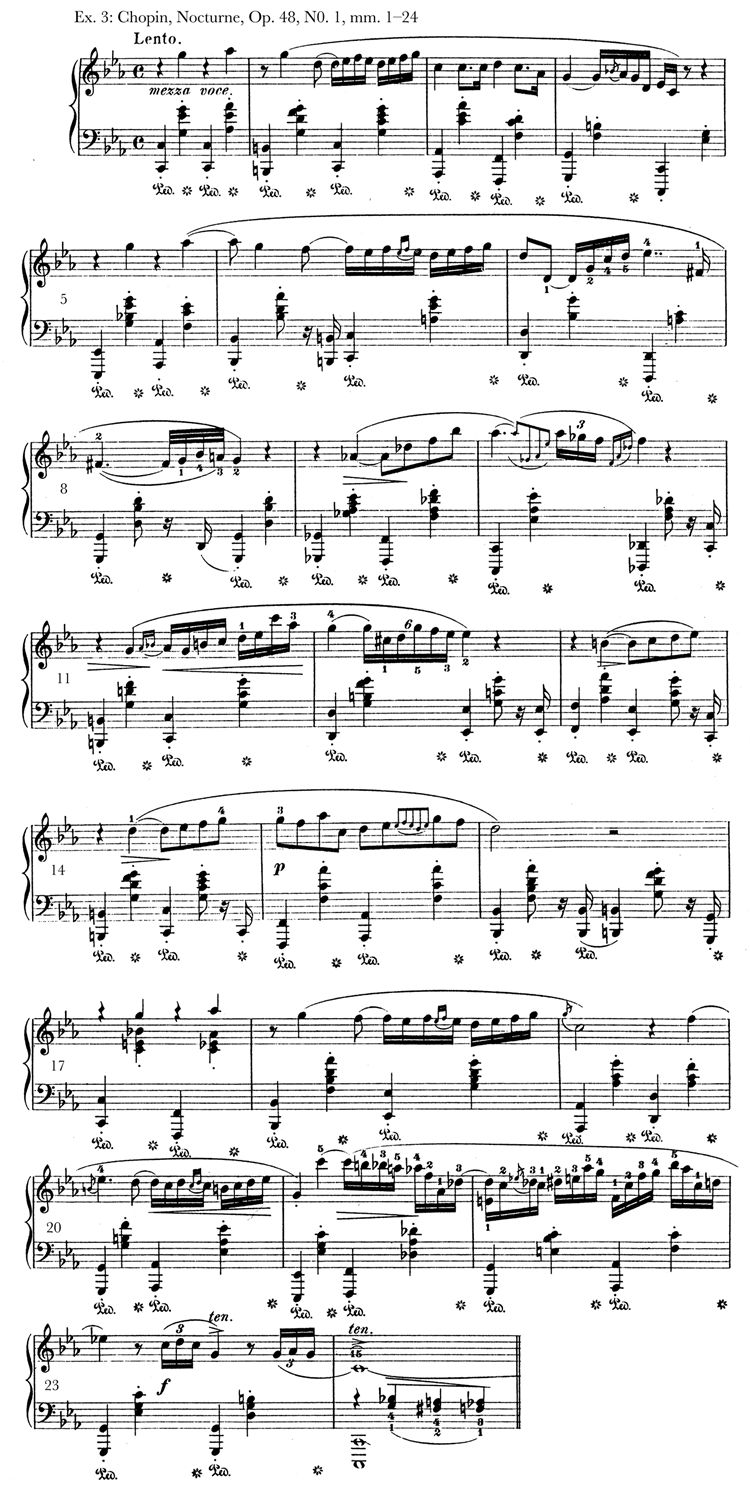

The spatial/somatic and emotive are fundamentally intertwined, such that one can often start in either domain and easily be led to the other. We witness this connection in Schenkerian analysis no less than in other realms. For example, the spatial/somatic notion of descent (as in the descending Urlinie) connotes other spatial/somatic notions such as closure and stability, which in turn have positive and reassuring associations. Ascent, by contrast, often has less comforting connotations of striving, struggle, and tension. These emotive associations derive from our experience of the physical world, in which succumbing to gravity and conforming to natural laws affords one a reassuring sense of resolution and comfort (as when an airplane lands), while resisting gravity can be unpleasant or unsettling (as when one takes off). Of course, in other contexts, the roles are reversed, but the point remains: physical motions have emotive correlates or consequences. Hence, if Schenkerian analysis frames musical processes in terms of our physical engagement with the world, it implicitly frames them in terms of our emotional reactions to such engagement.25 Moreover, Schenker himself often renders the emotive potential of his own theory explicit in narrative, anthropomorphic analyses that belie the formalist disposition with which he is commonly associated.26 Such a narrative approach is bound to render analysis even more relevant to performance than an examination of isolated physical and emotive dispositions, for it will expose a more multidimensional, complex human condition that the performer can more readily identify with, physically embody, and musically project through sound, touch, and time. I shall attempt such a narrative analysis of the first section of Chopin's Nocturne, op. 48, no. 1 (Example 3).

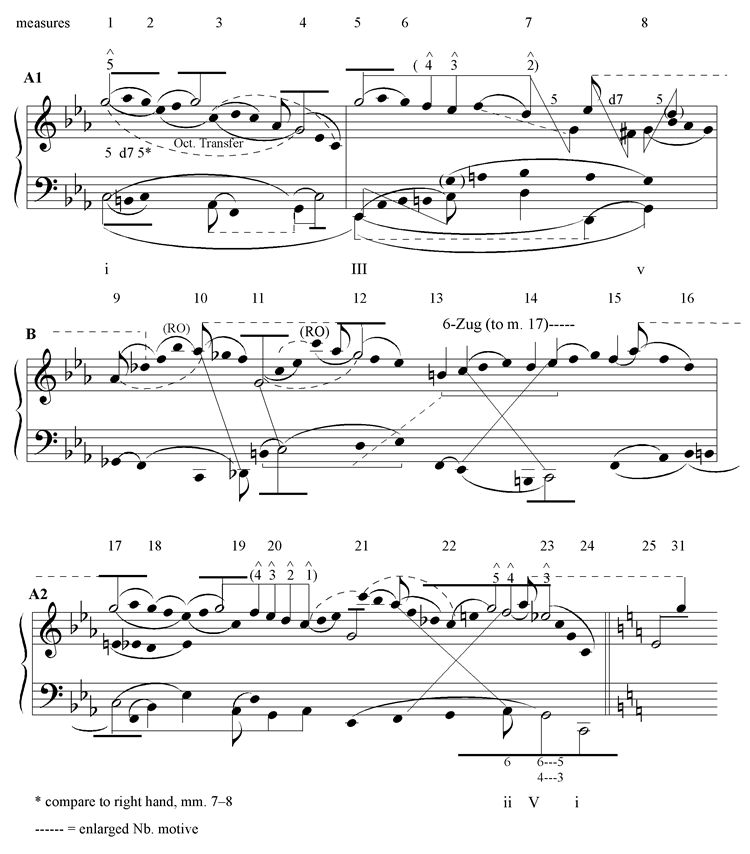

First phrase, mm. 1-4: Analysis

Mm. 1-2 establish an upper neighbor (Nb.) motive consisting of G-A-flat-G ( -

- -

- ), which is mirrored by a lower neighbor motive in the bass (C-B-C). The Nb. motive embellishes the G Kopfton, which is then unfolded by a

), which is mirrored by a lower neighbor motive in the bass (C-B-C). The Nb. motive embellishes the G Kopfton, which is then unfolded by a  -

- -

- arpeggiation (mm. 1-31) (Ex. 4). The potential tonic support of the C5 that ends this arpeggiation is undermined by the A-flat in the bass; additionally, C5 itself is overshadowed by the emphasis on the Kopfton (and Nb. motive) at the beginning and end of the phrase and by the octave transfer the Kopfton undergoes over the course of the phrase. Hence, the tonic pitch on m. 31 is subtly weakened both locally due to its harmonization and more globally due to its subsumption by the octave transfer of G. The quality of weakness that is established and exemplified by this suggestive detail is differently manifested at the end of the phrase: in m. 4, C4 (itself octave-transferred from C5 in m. 3) is now harmonized by i, but such potential strength and resolution is undermined by C's own transience, resulting from the accelerated and abruptly terminated rhythm. The C, a mere sixteenth note placed off the beat, evaporates into thin air. Moreover, neither tonic pitch in the melody is approached via a linear descent; in other words, the Kopfton G is prolonged solely by arpeggiations rather than by linear progressions. Thus, both tonic pitches in the melody of this phrase fail to achieve a sense of stability or closure. As we shall see, the search for these qualities will provide a narrative arch throughout this section.

arpeggiation (mm. 1-31) (Ex. 4). The potential tonic support of the C5 that ends this arpeggiation is undermined by the A-flat in the bass; additionally, C5 itself is overshadowed by the emphasis on the Kopfton (and Nb. motive) at the beginning and end of the phrase and by the octave transfer the Kopfton undergoes over the course of the phrase. Hence, the tonic pitch on m. 31 is subtly weakened both locally due to its harmonization and more globally due to its subsumption by the octave transfer of G. The quality of weakness that is established and exemplified by this suggestive detail is differently manifested at the end of the phrase: in m. 4, C4 (itself octave-transferred from C5 in m. 3) is now harmonized by i, but such potential strength and resolution is undermined by C's own transience, resulting from the accelerated and abruptly terminated rhythm. The C, a mere sixteenth note placed off the beat, evaporates into thin air. Moreover, neither tonic pitch in the melody is approached via a linear descent; in other words, the Kopfton G is prolonged solely by arpeggiations rather than by linear progressions. Thus, both tonic pitches in the melody of this phrase fail to achieve a sense of stability or closure. As we shall see, the search for these qualities will provide a narrative arch throughout this section.

The quality of weakness as implied by the voice-leading is amply exemplified by foreground elements. The  -

- motive found in mm. 1-2 is a quintessential, romantic motive of longing and anxiety; as presented here, with its curious rhythmic setting dominated by strong-beat rests, it establishes, along with the minor key, a reticent, anxious, and ambivalent mood at the outset (hence contradicting the qualities of stability and clarity conventionally associated with a beginning). This motive shifts to the bass in mm. 3-4; as a larger-scale bass motion, it has the capacity to permeate more of the phrase with its sullen mood; being in the bass also allows the motive to affect other, namely melodic, elements—specifically, it is responsible for the weak harmonization of C in m. 3. It is as if this anxious emotion is initially conscious (i.e., the melody, mm. 1-2) and subsequently descends to a deeper, more unconscious level (i.e., the bass, mm. 3-4), creating a more deleterious effect. Another foreground element is the melody's descending fifth (G-C) into m. 3,27 which can be construed as a sigh motive, and thus directly anticipates the more substantive shift toward weakness that occurs on the downbeat of m. 3. What follows is a funeral march topic, which constitutes the zenith of pathos within the phrase. Both the sigh and funereal motives exemplify the structural qualities of weakness and instability.28 The end of the phrase, as mentioned, contains a rhythmic thrust that contributes to the lack of closure; the stretto indicated in some editions serves to exemplify the inbuilt acceleration and consequent tonal irresolution. In sum, the features of mode, motive, topos, and rhythm all have affective associations that exemplify those implicit in the voice-leading analysis.

motive found in mm. 1-2 is a quintessential, romantic motive of longing and anxiety; as presented here, with its curious rhythmic setting dominated by strong-beat rests, it establishes, along with the minor key, a reticent, anxious, and ambivalent mood at the outset (hence contradicting the qualities of stability and clarity conventionally associated with a beginning). This motive shifts to the bass in mm. 3-4; as a larger-scale bass motion, it has the capacity to permeate more of the phrase with its sullen mood; being in the bass also allows the motive to affect other, namely melodic, elements—specifically, it is responsible for the weak harmonization of C in m. 3. It is as if this anxious emotion is initially conscious (i.e., the melody, mm. 1-2) and subsequently descends to a deeper, more unconscious level (i.e., the bass, mm. 3-4), creating a more deleterious effect. Another foreground element is the melody's descending fifth (G-C) into m. 3,27 which can be construed as a sigh motive, and thus directly anticipates the more substantive shift toward weakness that occurs on the downbeat of m. 3. What follows is a funeral march topic, which constitutes the zenith of pathos within the phrase. Both the sigh and funereal motives exemplify the structural qualities of weakness and instability.28 The end of the phrase, as mentioned, contains a rhythmic thrust that contributes to the lack of closure; the stretto indicated in some editions serves to exemplify the inbuilt acceleration and consequent tonal irresolution. In sum, the features of mode, motive, topos, and rhythm all have affective associations that exemplify those implicit in the voice-leading analysis.

First Phrase: Performance

The structure and surface signify a constellation of related affects we may variously describe as weakness, tentativeness, anxiety, tension, pessimism, etc.29 On a general level, these qualities can be expressed through slightly unsteady timing and a weak sound. More specifically, the absence of a linear dynamic trajectory, i.e., a steady crescendo leading to a distinct point of arrival, will directly exemplify the absence of voice-leading linearity and tonal resolution. Incidentally, the pianist may also gently accelerate in m. 2, in order to exemplify the acceleration from a quarter-note to an eighth-note to a sixteenth-note pulse, and then pull back decisively in m. 3 in order to consolidate the new, morose feeling.

Second phrase, mm. 5-8: Analysis

The previous gap between G and E-flat (as part of the arpeggiation, mm. 1-3) is now filled by F (m. 6), which establishes a line that continues to D in m. 7. This  -

- -

- -

- progression thus supplies the linearity that was conspicuously absent from the first phrase, and seems to promise a resolution to and proper harmonic support of

progression thus supplies the linearity that was conspicuously absent from the first phrase, and seems to promise a resolution to and proper harmonic support of  (especially when the tonality turns abruptly from the relative major back to the home key in m. 63). This promise, however, is quickly broken: no sooner does D arrive than we shift toward the key of g (v), and hence are not in a tonal position from which to resolve to C. Instead, D ascends to E-flat, which reinforces the denial of closure in two ways. First, it is part of an implied

(especially when the tonality turns abruptly from the relative major back to the home key in m. 63). This promise, however, is quickly broken: no sooner does D arrive than we shift toward the key of g (v), and hence are not in a tonal position from which to resolve to C. Instead, D ascends to E-flat, which reinforces the denial of closure in two ways. First, it is part of an implied  -

- motive (within the key of v), whose signification of tension here seems to emanate from and comment upon the voice-leading predicament. Second, the E-flat (m. 7) is conspicuously isolated in terms of register and does not resolve directly to the expected D, but rather (arguably) to D-flat in next phrase, m. 9 (see dotted line in graph). Hence, the promise of even local linearity is foiled and deferred.

motive (within the key of v), whose signification of tension here seems to emanate from and comment upon the voice-leading predicament. Second, the E-flat (m. 7) is conspicuously isolated in terms of register and does not resolve directly to the expected D, but rather (arguably) to D-flat in next phrase, m. 9 (see dotted line in graph). Hence, the promise of even local linearity is foiled and deferred.

The above-cited tonicization of v is preceded by one of III. On a surface level, III coincides with the increased linearity; together, they connote amelioration and optimism. By contrast, v coincides with the loss of linearity, and consequently of hope. Yet, on a deeper level, III can be understood as a long-range neighbor to the v/v (forming another Nb. motive in the bass, as in the first phrase; see Ex. 4). III is thus subsumed on a deeper level by v; analogously, the hope it signifies is subverted by the anxiety signified by the minor mode. For that matter, the initial three Stufen of i-III-v taken together can be seen as an unfolding of the tonic triad, suggesting perhaps that the essentially pessimistic mood of the minor tonic underlies the entire section, rendering any change of mood suggested by III illusory.

As for foreground features, the tied A-flat in mm. 5-6 precludes a recurrence of the rest that had occurred in m. 21, and thus directly exemplifies the broader qualities of connectedness and directionality associated with voice-leading linearity. That is, the more abstract process by which a melodic gap is subsequently filled is exemplified by the more tangible process by which a rest is filled with sound. Second, the loss of linearity and hope in m. 7 is immediately presaged by the rhythmically conspicuous B-C motive in the bass of m. 6, which recalls the initial phrase and its predicament and also serves as a pivot upon which we begin the transition back to a minor key (v). The motive can be seen as representing a psychological shift, an intrusion of memory, which recalls an undesirable state and is conducive to reverting to it. Finally, following that unpropitious motive, all hope of linearity is immediately quashed with the octave drop at the beginning of m. 7 and the resultant disillusionment is then topically reinforced by a sigh figure (E-flat5-F-sharp4)—which is all the more potent because it occurs on the expressively charged  (due to its association with the Nb. motive).

(due to its association with the Nb. motive).

Second Phrase: Performance

Hence, unlike the initial phrase that expresses basically a single emotional state, this phrase expresses two: attainment then loss of hope (of achieving stability and fulfillment). A performer following this reading would thus sharply dichotomize this phrase, playing the first half with a distinct sense of security and linearity, the second in a more disoriented, erratic manner. The emotional shift as represented by B-C in the bass of m. 6 can be played abruptly and intrusively. Transcending this break, however, is the  -

- -

- -

- line that arrives on m. 71. The performer can express this ephemeral linearity by exaggerating the sense of line, both by playing molto legato (perhaps even elongating the initial G5 in m. 5 to anticipate the imminent over-the-bar connection) and by applying directional dynamics, arriving decisively upon D5 m. 7; it is crucial, I think, to differentiate dynamically between the arrival on that note and the one on E-flat (m. 73), as the former connotes affirmation, the latter anxious deviation. The E-flat is the longest note in the phrase and undoubtedly the climax of the piece thus far; it fully consolidates the initial state and is all the more indignant for having seen a glimpse of a solution. This one note, therefore, played with sufficient intensity, can encapsulate a complex mental state. A subito piano on F-sharp (last note, m. 7) will have a threefold purpose: to express the sigh figure, to isolate dynamically the E-flat5 (i.e., to exemplify directly its registral isolation and in turn the loss of linearity), and to induce a soft dynamic for the end of the phrase, which will foreground the lack of closure.30

line that arrives on m. 71. The performer can express this ephemeral linearity by exaggerating the sense of line, both by playing molto legato (perhaps even elongating the initial G5 in m. 5 to anticipate the imminent over-the-bar connection) and by applying directional dynamics, arriving decisively upon D5 m. 7; it is crucial, I think, to differentiate dynamically between the arrival on that note and the one on E-flat (m. 73), as the former connotes affirmation, the latter anxious deviation. The E-flat is the longest note in the phrase and undoubtedly the climax of the piece thus far; it fully consolidates the initial state and is all the more indignant for having seen a glimpse of a solution. This one note, therefore, played with sufficient intensity, can encapsulate a complex mental state. A subito piano on F-sharp (last note, m. 7) will have a threefold purpose: to express the sigh figure, to isolate dynamically the E-flat5 (i.e., to exemplify directly its registral isolation and in turn the loss of linearity), and to induce a soft dynamic for the end of the phrase, which will foreground the lack of closure.30

The ambiguity of III presents a considerable challenge to the performer: how does she handle its multiple connotations? On a surface level, as we have seen, it expresses optimism and resolution, while on a deeper level, it is subsumed by pathos and instability. Of course, one could simply express the latter on account of the former being in some sense illusory—perhaps by resisting the temptation to brighten the color on m. 5 but instead retaining the general sound of the previous phrase, exemplifying the subsumption of III by i. Alternatively, one could fully indulge in the glimmer of hope and not express in any way its subsumption by i nor anticipate its motion to v. Yet a third option, which I think preferable, would be somehow to capture the polysemy of the moment, perhaps by furnishing a bright color, but at the same time, resisting too firm a grounding in that key, instead projecting its inherent instability and mobility as an upper neighbor within v. In this rendition, the performer will not feel or allow the listener to feel metrically grounded in the section, but will infuse the passage with a sense of imminent slippage or unease. In short, this moment surrounding III is a small but revealing example of the potential correlation between structural and emotional complexity: to expose structural levels is to expose the various affective levels to be conveyed.

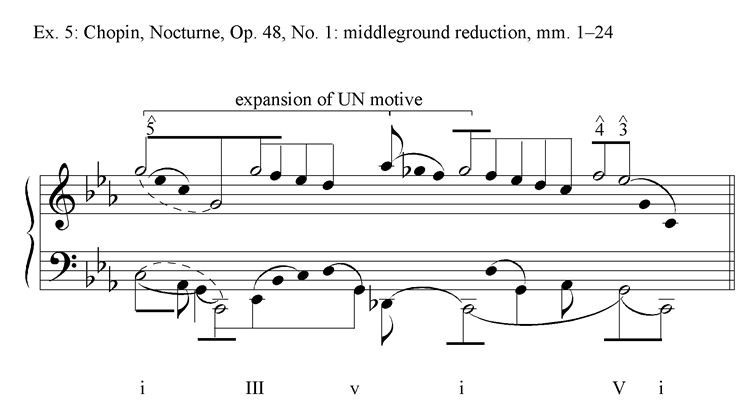

Third phrase, mm. 9-16: Analysis

Up to this point, the analysis has yielded qualities that inextricably link the physical and emotive. The lack of linear resolution in the first phrase intimated both physical and emotional weakness, while the initial presence of linearity in the second phrase intimated both physical and emotional security. This phrase, however, seems to foreground purely physical qualities (as perhaps befits its developmental function as a ternary B section), boasting no fewer than four distinct somatic/spatial techniques, some of which have multiple instances.

(1) Motivic Enlargement: The

-

(A-flat-G) motive is enlarged over the span of four measures (mm. 9-12); mm. 1-12 thus constitute an enlargement of the complete Nb. motive of mm. 1-2 (G-A-flat-G) (see Example 5).

(2) Octave Displacement and Alternation: Each pitch of the Nb. motive (A-flat and G, mm. 9-12) is octave-transferred (see Example 4). This event frames the more extensive registral play that occurs in m. 10, where a descending third motion of A-flat-G-flat-F is played out in two registers simultaneously (Example 6). Chopin apparently wanted this registral dialogue to be audible, given the downward stems he notates.

(3) Reaching Over: The A-flat of the Nb. motive receives its own neighbor (B-flat5) in m. 9, which is a reaching over (a second in the middleground is compounded to a ninth in the foreground). This maneuver creates the space for additional motivic content31 and recaptures the obligatory register. Likewise, C6 on the last eighth of m. 11 reaches over the upper voice containing A-flat5 (it is an octave displacement of the inner voice C5 three notes prior).

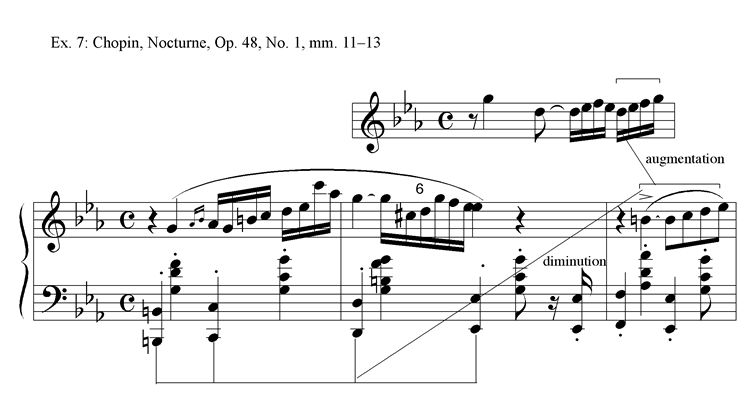

(4) Motivic Compression: There are at least four instances of motivic compression. First, the octave alternation in m. 10 referred to above can be seen as a compression of the broader octave alternation of the tones of the Nb. motive by which it is surrounded (see Example 6). Second, the motion of A-flat5-G into m. 12 is a slight parallelism and compression of the Nb. motive, an audible exemplification of the larger Nb. motive that governs the four-bar phrase. Third, the right hand of m. 13 constitutes a parallelism of the bass line of the previous two measures (see bracket in Example 4). However, notice that this figure can also be understood as an augmentation of the ascending fourth cell of the theme (m. 24). This figure is thus a diminution and an augmentation simultaneously (Example 7), creating a sense of ambiguity. Finally, the melismatic ornamentation of m. 15 (leading into beat 4) encapsulates the melodic configuration of the last half of m. 2 and m. 6; this subtly prepares for the thematic return of m. 17.

Example 4. Chopin, Nocturne, Op. 48, no. 1, mm. 1-25: Voice Leading Analysis

Third Phrase: Performance

Generally, this section is marked by expansiveness, in terms of both the exploration of vertical, registral space and the linear expansion of the Nb. motive. The performer can express this quality, in general, by employing a broader spectrum of dynamic and tempo fluctuations than he has hitherto employed, and by expressing a sense of strain and of resisting gravity (with subtle ritardandos) on the octave transfers and reachings over. (M. 10, by contrast, involves considerable compression, and can thus be played with a hurried quality.) For a more specific recommendation, one can highlight the bass line in mm. 11-12 due to its motivic significance, and so the listener can perceive its subsequent imitation by the right hand in m. 13 (bearing in mind that to "highlight" the bass is not merely to bring out the individual pitches, but to shape them as a coherent line). That imitation, in turn, because of its rhythmic ambiguity as explained above, can perhaps be played with a sense of push and pull, as if not knowing whether to be fast or slow.

Fourth phrase, mm. 17-24: Analysis

The opening is quite fluid harmonically; it employs a descending fifth sequence that touches upon both initial Stufen (i and III).32 It also recalls the elements of disconnection and connection associated with those respective Stufen, namely, the downbeat rest of the second measure is reinstated, recalling the first phrase associated with i. On the other hand, the G-E- flat gap is filled by F, recalling the second phrase associated with III. In this way, this phrase compresses events or elements that previously belonged to separate phrases into a single phrase. Our narrative is reaching a climax; the conflicting elements of linearity and non-linearity are coming to a head within an intensified harmonic motion that seems to signal a more fervent desire and active search for a resolution of the predicament. At long last, we arrive upon  via a linear descent (m. 20), but it still does not receive definitive, tonic support, as it is once again weakly supported by the upper-neighbor A-flat. As in m. 7, the lack of closure is immediately reinforced by a registral gap, this time, by the audacious melodic leap of an ascending eleventh; a probing musical soliloquy (mm. 21-23) then explores the space opened by that leap, as if futilely searching for something affirmational to cling to within this chasm. Such intrinsic logic and linearity is actually to be found concealed within the intricate folds of this melisma; as the graph reveals, this passage embeds a fragment of the initial melody (G-A-flat-G-F-E-flat), bringing the fundamental line down as far as E-flat, but not reaching C.33 In its searching, circuitous contour, within which is nested a comprehensible melodic line, this passage can thus be read as a peroration on the search for closure and the problematics and obstacles involved in such a search; it intensely encapsulates the dialectic of resolution and tension, connection and alienation, played out since the beginning.

via a linear descent (m. 20), but it still does not receive definitive, tonic support, as it is once again weakly supported by the upper-neighbor A-flat. As in m. 7, the lack of closure is immediately reinforced by a registral gap, this time, by the audacious melodic leap of an ascending eleventh; a probing musical soliloquy (mm. 21-23) then explores the space opened by that leap, as if futilely searching for something affirmational to cling to within this chasm. Such intrinsic logic and linearity is actually to be found concealed within the intricate folds of this melisma; as the graph reveals, this passage embeds a fragment of the initial melody (G-A-flat-G-F-E-flat), bringing the fundamental line down as far as E-flat, but not reaching C.33 In its searching, circuitous contour, within which is nested a comprehensible melodic line, this passage can thus be read as a peroration on the search for closure and the problematics and obstacles involved in such a search; it intensely encapsulates the dialectic of resolution and tension, connection and alienation, played out since the beginning.

Fourth Phrase: Performance

The beginning of this phrase, I feel, strongly calls for being played with a sense of forward motion, to indicate both the compression of events and the intensified search and yearning for closure. The figuration in mm. 21-231 is the most difficult interpretively, but an awareness of its underlying thematic contour should afford the performer some basis on which to shape it. But again, it is not primarily a matter of bringing out the embedded thematic notes but of responding to the emotive and narrative significance of their embedding: that is, the fervent desire for a sense of a linear orientation and rationality in the midst of a seemingly insoluble predicament. The dialectic of underlying motive and foreground figuration, because of the emotional complexity it embodies, will yield far more substantive and numerous interpretive possibilities than the underlying motive itself (and the imperative to "project it"). Overall, this phrase, in its juxtaposition of elements, effusive figuration, and equivocal resolution, encodes the most complex mental state in the piece thus far. Moreover, the more multidimensional the state is, the more a sheer recognition of it via structural analysis will naturally affect a performer and the less one can prescribe how it will. This is why my performance recommendations for this phrase were rather general.

The end of the piece (Example 8) fares no better in terms of achieving decisive closure, for it lacks a full-fledged linear descent into the final tonic of the melody, and harmonically, the expected perfect authentic cadence in m. 72 is subverted (evaded) by a brazen 4/2 chord.34 In the end, then, we have an incomplete linear progression—merely the  -

- -

- of a

of a  -line Urlinie. While such a reading is inconsistent with standard Schenkerian practice, I believe it is consistent with the events of the piece in particular, Chopin's style in general.35 The incomplete Urlinie serves as a structural metaphor for, and embodiment of, the sense of physical and emotional debility that is the piece's expressive core. The sense of a gap, as epitomized by the feeble opening measure with its conspicuous rests, is shown to operate on the largest scale by the incomplete Urlinie, with its gap in large-scale structure, i.e., the gap between where we actually end and where we know we could or should be, between what we have and what we wish to attain.36

-line Urlinie. While such a reading is inconsistent with standard Schenkerian practice, I believe it is consistent with the events of the piece in particular, Chopin's style in general.35 The incomplete Urlinie serves as a structural metaphor for, and embodiment of, the sense of physical and emotional debility that is the piece's expressive core. The sense of a gap, as epitomized by the feeble opening measure with its conspicuous rests, is shown to operate on the largest scale by the incomplete Urlinie, with its gap in large-scale structure, i.e., the gap between where we actually end and where we know we could or should be, between what we have and what we wish to attain.36

The Nocturne, then, as perceived through the filter of my Schenkerian and semiotic reading, is a veritable character study. It portrays a persona who in his essence is feeble and uncertain, perhaps afraid, but who more locally undergoes a range of feelings and corresponding physical stances. The pianist following this reading would, like an actor, simultaneously embody and convey the most deep-seated as well as the more transient emotive states.37 Importantly, the narrative premise of weakness and striving for stability, perhaps no more than a potentiality within the piece (at times strong, at other times somewhat faint), is consolidated by the application of the Urlinie, Zug, and other Schenkerian constructs. Without a Schenkerian reading, such a potentiality might easily remain latent; indeed, I believe a Schenkerian reading of any piece is at root a mandate to imagine precisely such a search for closure, and the many obstacles and deviations encountered along the way—Schenkerian analysis is ideally suited to elicit this particular mode of engagement with the work.

Conclusion

I hope to have shown that Schenkerian analysis and performance are by their nature deeply compatible. While the former is not itself a material medium, it nonetheless strongly embodies the potential for such materiality, which is realized in performance. Somatic and affective experience conditions the formulation of Schenkerian concepts and constructs, and such experience can be recovered and actualized in performance. To be unabashedly metaphorical, it is as if Schenker's metaphors freeze real experience and thaw upon contact with the warmth of the performed music to which they are applied, becoming actual again. I have also suggested that the potential for Schenkerian analysis to function somatically and expressively has as much to do—if not more—with the way it is used as with the internal components of the system itself. That is, one must appropriate its constructs as meaningful only insofar as they are conjoined to the musical surface. That is, if we choose Schenkerian analysis based on its rich potential for performance, we would want to employ it for readings that exploit such potential—that reveal the human states embodied by a piece.

I have also suggested that the more anthropomorphically we read a piece, the more naturally it can be applied to performance. Once the pianist uncovers the affects connoted by analytical constructs, and then identifies with these feelings on some level (assuming she can), they will inevitably and naturally affect her rendering of the passage. This is because the pianist who truly empathizes with (if not actually feels) these human states will be likely to project the sense of sound and movement that typifies such states. Indeed, a Schenkerian analysis, employed in a metaphorical spirit, exposes states that are so fundamentally human and that elicit such empathy from the performer that little deliberate "application" from analysis to performance need be done. In other words, the ideal use of analysis, in my view, is to arrive at an exegesis of a piece that is itself so experiential, so implicative of a physical and expressive stance, as to obviate any need for conscious or rational translation.38

Yet, as I have also suggested, such an approach, as rooted as it is in mutual consonances between analysis and performance, paradoxically foregrounds the ineluctable tensions between them.39 For the metaphorical qualities that arise from my methodology are general, and thus will inevitably receive very different realizations from different performers. Moreover, a human-oriented approach to analysis will need to allow for the subjective inclinations of the performer, for the possibility that she will realize a structural quality in an unexpected way, adding nuances that modify established meanings and even lead to new ones. Simply put, while a broad correlation exists between Schenkerian analysis and performance in that both thrive on physical and expressive qualities, no exact, predictable, and measurable correlation does; this should not be a source of regret.40

List of References

Agawu, Kofi. Playing with Signs: A Semiotic Interpretation of Classic Music. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1991.

Bach, C. P. E., Essay on the True Art of Playing Keyboard Instruments [1753], trans. William J. Mitchell. New York: W. W. Norton, 1949.

Berry, Wallace. Musical Structure and Performance. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1989.

Cook, Nicholas. "Analysing Performance and Performing Analysis." In Rethinking Music, ed. Nicholas Cook and Mark Everist. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999, pp. 239-61.

_____. "Music Theory and 'Good Comparison': A Viennese Perspective," Journal of Music Theory, 33/1: 117-42.

Eigeldinger, Jean-Jacques. Chopin Pianist and Teacher As Seen by His Pupils. Cam- bridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986.

Folio, Cynthia. "Analysis and Performance of the Flute Sonatas of J. S. Bach: A Sample Lesson Plan," Journal of Music Theory Pedagogy, 5/2 (1991): 133-59.

Keiler, Allan R. "On Some Properties of Schenker's Pitch Derivations," Music Perception 1/2 (1983-84): 200-28.

Langer, Susanne K. Feeling and Form. New York: Charles Scribner and Sons, 1953.

_____. Philosophy in a New Key: A Study in the Symbolism of Reason, Rite, and Art. 3rd ed. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1957.

Lester, Joel. "Performance and Analysis: Interaction and Interpretation" In The Practice of Performance: Studies in Musical Interpretation, ed. John Rink. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995, pp. 197-216.

Meyer, Leonard B. Explaining Music: Essays and Explorations. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1973.

Narmour, Eugene. "On the Relationship of Analytical Theory to Performance and Interpretation." In Explorations in Music, The Arts, and Ideas: Essays in Honor of Leonard B. Meyer. Stuyvesant: Pendragon, 1988, pp. 317-40.

Nolan, Catherine. "Reflections on the Relationship of Analysis and Performance," College Music Symposium, 33/34 (1993-94): 112-39.

Pierce, Alexandra. "Developing Schenkerian Hearing and Performing," Intégral 8 (1994): 51-123.

____. Spanning: Essays on Music Theory, Performance, and Movement. Redlands: The Center of Balance Press, 1983.

Proctor, Gregory. Review of Schenker, Free Composition, Notes 36/4, 879-81.

Rosenblum, Sandra P. Performance Practices in Classic Piano Music. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1988.

Rothstein, William. "Heinrich Schenker as an Interpreter of Beethoven's Piano Sonatas," 19th-Century Music, 8/1 (1984): 3-28.

Samson, Jim. "Chopin's Alternatives to Monotonality: A Historical Perspective." In The Second Practice of Nineteenth-Century Tonality, eds. William Kinderman and Harald Krebs. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1996, 34-44.

Saslaw, Janna K. "Life Forces: Conceptual Structures in Schenker's Free Composition and Schoenberg's The Musical Idea," Theory and Practice, 22/23 (1997-98): 17-33.

Schachter, Carl. "20th-Century Analysis and Mozart Performance," Early Music, 19/4 (1991): 620-25.

_____. "Taking Care of the Sense: A Schenkerian Pedagogy for Performers," Tijdscrift Voor Muziektheorie, 6/3 (2001): 159-70.

Schenker, Heinrich. "Abolish the Phrasing Slur," trans. William Drabkin, The Masterwork in Music: A Yearbook. Vol. I. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994, pp. 20-30.

_____. The Art of Performance, trans. Irene Schreier Scott. New York: Oxford University Press, 2000.

_____. Die letzten fünf Sonaten von Beethoven: Kritische Ausgabe mit Einführung und Erläuterung. [Sonate As dur op. 110.] Vienna: Universal Edition, 1914.

_____. Free Composition (Der freie Satz). Trans. and ed. Ernst Oster. New York: Schirmer, 1935.

_____. "Further Considerations of the Urlinie I," trans. John Rothgeb, The Masterwork in Music. Vol. 1, ed. William Drabkin. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994, pp. 104-11.

Smith, Charles J. "Musical Form and Fundamental Structure: An Investigation of Schenker's 'Formenlehre'," Music Analysis, 15/2-3 (1996): 191-297.

Snarrenberg, Robert. Schenker's Interpretive Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

Swinkin, Jeffrey. "Reference and Schenkerian Structure: Toward a Theory of Varia- tion," Indiana Theory Review, 25 (2004): 177-221.

Van Den Toorn, Pieter C. Music, Politics, and the Academy. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995.

Zbikowski, Lawrence M. Conceptualizing Music: Cognitive Structure, Theory, and Analysis. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002.

Endnotes

1Wallace Berry embraces this model in Musical Structure and Performance. Eugene Narmour seems to as well, for, in his "On the Relationship of Analytical Theory," he often speaks of "correct" or "incorrect" performances, based on their conformity, or lack thereof, to a correct analysis.

2As a consequence, one can compare an analysis and a performance in a manner similar to comparing two analyses; Joel Lester does precisely that in "Performance and Analysis," in which he compares Schenker's and Horowitz's structural readings of the second movement of Mozart's Piano Sonata, K. 331.

3Langer, Philosophy in a New Key, 53-78.

4Langer, Feeling and Form, 104-48.

5I cannot provide a full-fledged philosophy of Schenkerian analysis here, but suffice it to say that all writers on Schenkerian analysis espouse either the discursive or presentational approach, or some dialectic of the two, whether consciously and explicitly or not. For an explicit testament to the former, see Agawu, Playing With Signs, 134: "Where analysis has recourse to music notation—as in Schenkerian graphs—the metalinguistic status of the analysis must be understood not as the expression of an idea 'in' music, but as the expression of a (necessarily) verbal idea in a notation that bears an iconic relation to the object-language." An explicit testament to the latter comes from Schenker himself, who adumbrates the artistic nature of analysis with the following oft-quoted statement at the beginning of Free Composition (xxiii): "The musical examples which accompany this volume are not merely practical aids; they have the same power and conviction as the visual aspect of the printed composition itself (the foreground). That is, the graphic representation is part of the actual composition, not merely an educational means."

6Folio, "Analysis and Performance of the Flute Sonatas."

7Ibid., Figures 4 and 5, 142-43.

8Needless to say, the long line phenomenon does not at root emanate from a literalistic construal of Schenkerian theory, as is evident by its popularity among performers and studio teachers, few of whom are directly influenced by Schenkerian analysis. Rather, I believe the reverse is more often the case: performers often come to Schenkerian analysis with a predilection for playing with a long line and construe the implications of the Urlinie in such a way as to validate that stance.

9See Schenker's diatribe against the substitution of uniformity for true unity in "Abolish the Phrasing Slur," 30. In this essay, as Schachter aptly summarizes, "he was urging performers to discard the featureless continuous legato suggested by 'phrasing slurs' of corrupt editions in favour of the varied and lively articulation shown in the composers' autograph." "20th-Century Analysis," 620.

10Proctor goes so far as to assert that "structural levels [are] ideas of reasonable musical processes . . . not . . . some of the notes in a piece; quoted in Smith, "Musical Form and Fundamental Structure," 278-79, which goes on to claim that the structural pitch itself is not nearly as important as "the formal-contrapuntal-harmonic process in which that pitch participates." Finally, Schachter states, "identifying structural elements should never become a goal in itself; the goal is to discover how those elements participate in what Schenker called 'das Drama des Ursatzes'—the drama of the fundamental structure." "Taking Care of the Sense," 168.

11Schenker himself viewed the structural levels as generative rather than reductive in nature; he seems to have viewed the generative process as the true artistic one (see "Further Consideration of the Urlinie I," esp. 107; discussed at length in Keiler, "On Some Properties"). In the terms of my current argument, what mattered most to Schenker was the Urlinie not as a factual end-product, but as a generator of musical content; any structural construct will be meaningful only insofar as it eventuates inis inextricably bound to the actual music.

12Cook, "Music Theory and Good Comparison."

13Of course, this is not as arbitrary as it sounds, for there is a reasonably good fit between the domains of species counterpoint and free composition; the Schenkerian metaphor thus seizes upon what is objectively present in music even as it extends it metaphorically. Clearly, not every metaphorical model will fit music equally well.

14In another instance, Cook describes analysis as "performative"—as entailing implicit assertions as to how the music should be heard or played; it is "an action disguised as fact," "Analysing Performance," 252. It is in this sense, perhaps, that analysis is "part of" the work, as Schenker contends (see fn. 5). That is, it is integral to the piece because it mandates how we are to hear certain of its aspects.

15Van Den Toorn, Music, Politics, and the Academy, 55.

16In the more explicit terms of Mark Johnson, Lawrence Zbikowski, and others, the source domain of space is mapped onto the target domain of time, serving to render it more tangible. See Zbikowski, Conceptualizing Music.

17Schenker associates the Urlinie with the notion of tone-space in Free Composition, 14. This second, voice-leading metaphor is also anthropomorphic in nature; most music-somatic metaphors will be, since the physicality ascribed to a musical process is more easily envisaged as enacted by an implicit musical persona rather than as motion in general. Saslaw expounds the somatic-metaphorical dimension of Schenker's (and Schoenberg's) theory in much greater depth in "Life Forces."

18Alternatively, mm. 3-41 could be viewed as an inversion of the lower third motion (C sharp-B-A) in mm. 1-31, in which case it would actually be an acceleration. In my view, the rhythmic broadness in m. 3 (relative to mm. 1 and 2) renders this reading less compelling.

19Cf. Snarrenberg's explication (Schenker's Interpretive Practice, 39-40) of Schenker's interpretation of this acceleration in his Free Composition graph (Fig. 141; Cf. Fig. 157).

20For more on the semiotics of musical exemplification, see my "Reference and Schenkerian Structure."

21Cf. Meyer's interesting interpretation of the second sf as actualizing for the first time in the theme a latent upbeat tendency. In this scenario, the performer would lead that chord decisively into the next bar. Explaining Music, 35.

22Schachter advocates a similar strategy in another context in "Taking Care of the Sense," 162.

23This is analogous to Langer's view that everything in a musical work serves music's most essential illusion of audible time and image of human feeling; even the text of a song, upon entering the domain of the musical work, ceases to be separately perceived as language and becomes yet another musical component. I believe the same can be said of analytical assertions. On this "principle of assimilation," see Feeling and Form, 149-68.

24C. P. E. Bach, to cite just one example, advocates what Sandra P. Rosenblum calls "contrametric rubato," in which one hand (usually the left) keeps strict time while the other plays more freely, and thus in which the two hands are out of sync within a measure. See Essay on the True Art, 161-62. Rosenblum outlines numerous situations in which performer-supplied tempo variance was sanctioned, such as when approaching a fermata or a structural joint, in order to characterize a contrasting theme, and within transitional sections. Performance Practices, 362-92.

25As Snarrenberg points out, Schenker himself posits an inextricable link between musical motion and emotion in the movement of Züge. Schenker's Interpretive Practice, 120.

26In particular, see his Erläuterungausgabe of Beethoven, op. 110, whose narrative premise—that of an enervated persona striving for greater vitality—is similar to my own in my reading of the Nocturne. See Snarrenberg's discussion of Schenker's reading, 108-20.

27This gesture can be seen as an intervallic expansion of the G5-D5 in m. 2.

28I owe the strategy of discerning relationships (congruence as well as disparity) between voice-leading structure and foreground topoi to Agawu's Playing with Signs.

29These words do not all mean the same thing of course, and by invoking them all I mean to convey not that the feeling of the passage is unclear, but that words can only approximately describe rather than precisely denote a musical affect.

30This interpretation is reinforced by the fingering that Chopin recommended to his student Dubois of 4 on E flat5 and 3 on F sharp4, suggesting that the two notes would be detached and isolated from each other, and that the second note would be played with a weaker dynamic, since whatever intensity had accumulated by the climax on E flat would be dissipated by the detachment. Eigeldinger, Chopin Pianist and Teacher, 264.

31The figure in m. 9 can be viewed as an intervallic expansion and augmentation of that in m. 7 (beginning on the second note).

32To be precise, the i here is replaced by V/IV, which, however, serves as a tonic substitute. An alternate harmonic reading might assert that, since the previous phrase cadenced on what is arguably a V/III (m. 161), and since we return to III in m. 18, the C7 chord here is subsumed by a prolongation of III (mm. 16-18)its tonicity thus denied. I shall not pursue the narrative or performance implications of this reading here.

33 One might posit a  in m. 23—not the one actually present in the music after beat 2, of course, which is merely an upper neighbor to C, but rather a mentally supplied pitch. However, I think the highly disjunct figuration in that measure does not lend itself to such a reading; a sense of linearity is palpably absent.

in m. 23—not the one actually present in the music after beat 2, of course, which is merely an upper neighbor to C, but rather a mentally supplied pitch. However, I think the highly disjunct figuration in that measure does not lend itself to such a reading; a sense of linearity is palpably absent.

34This chord arises from a descending chromatic motive in the bass, such as occurred in mm. 84-9.

35Chopin, as is well known, often expresses a somewhat anxious attitude toward the notion of closure, both in his bitonal pieces (as the Ballade, op. 38) and his frenetic, idiosyncratic codas (as in the Ballade, op. 52). On the former, see Samson, "Chopin's Alternatives to Monotonality."

36See Smith's call for an enlarged repository of Ursätze in order to relate inner structure and outer form more convincingly as well as to account for the peculiarities of nineteenth-century music ("Musical Form and Fundamental Structure," esp. 263 and 266). I would add that a larger range of structural prototypes would provide structural metaphors for a greater range of emotive and existential circumstances as embodied in music.

37On a pedagogical approach to embodying expressive states that derive from Schenkerian analysis, see Pierce, "Developing Schenkerian Hearing and Performing"; see Spanning for a broader overview of Pierce's approach to performance and movement.

38Schenker himself seems to have advocated this unself-conscious approach to the relation between analysis and performance. Rothstein, for example, suggests that Schenker conveyed many of his recommendations for performance based upon analytical insights (regarding dynamics, articulation, phrasing, etc.) in the form of fingerings (as in his edition of the Beethoven piano sonatas) as opposed to more explicit indications, so that the pianist would relate to these insights on a kinesthetic level, thus executing them naturally, without cognitive mediation or exaggeration. "Heinrich Schenker as an Interpreter."

39See Nolan, "Reflections on the Relationship of Analysis and Performance."

40I would like to thank my colleague Rachael Hutchings and my student James Bovee for their very thoughtful and helpful comments on earlier drafts of this paper.