Throughout the twentieth-century musical composition was characterized by the evolution of two distinct traditions that developed simultaneously and in opposition to one another. As a number of critics and historians have noted, these traditions together defined what has come to be known as Modernism.1 One was an extension of the organicism of the late nineteenth century, in which form arises from the direct interaction of artist with materials, and form is seen as inherent in its materials. In an organic conception of form content and form are one; form is a direct product of the innate qualities of the materials used in its creation. With respect to organic form, nothing exists apriori. In contrast, another, very different, less organic approach emerged in which materials and form were treated as independent of one another. In the latter, form arose not from the nature of its materials but rather as an abstraction that exists independent of any specific characteristics of the materials from which it was made. Neither tradition alone is sufficient to account for the richness and diversity of creative activity in the Modern era. Each is an equal, though opposite, component of the music of that epoch, and each gives meaning to its counterpart.

I believe that, among early twentieth-century composers, Erik Satie most consistently embodies the inorganic approach. Indeed, I believe that he is the key figure in the emergence of this significant branch of the Modernist tradition. At one point in my recent study of John Cage’s Amores, I made what some may perceive as a provocative statement that, with regard to a history of early Modernism in music, only a “naïve or biased examination of [this era in] music would ignore Satie when considering Schoenberg (or vice-versa); just as one would never ignore either Gertrude Stein or T. S. Eliot when considering early Modern poetry.”2 It is this belief that has led me to the present study, an attempt to identify the ways in which Satie’s music exemplifies this second tradition and lays the foundation for the music of many of the most significant composers after the Second World War, including Cage, Morton Feldman, Earle Brown, Christian Wolff, and Alvin Lucier, to name but a few. Indeed, Cage himself makes this connection through his own path-breaking essay on Satie in his book Silence (1973), as well as through his gloss on Satie’s masterpiece Socrate in a series of compositions entitled Cheap Imitation (in versions for piano solo, 1969; orchestra,1972; violin solo,1977).3

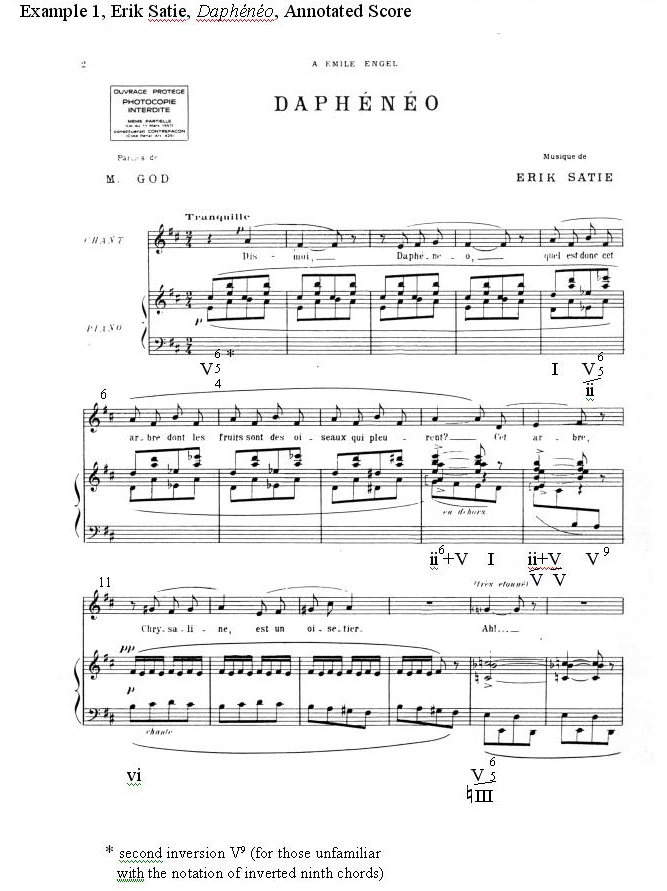

In this essay, I will examine, in detail, the song Daphénéo, the second of a set of three songs entitled Trois Mélodies that Satie composed in 1916 (Example 1).4 For the purpose of comparison, I will conclude by contrasting Satie’s methods with an example of the more organic approach to composition drawn from the same period, the opening of Alban Berg’s well known Piano Sonata, Op. 1 (1907-08).5 A comparison of the very different treatment of harmony, voice leading and rhythm by these two composers will highlight the differences between their styles.

Example 1, Erik Satie, Dapheneo, Annotated Score

Daphénéo

The poem Daphénéo was written by Mimie Godebska (cited on the score as M. God) the seventeen year old daughter of Cipa and Ida Godebski, friends of Satie and many other composers and artists of the day. (Indeed, Mimie and her brother Jean were the dedicatees of Maurice Ravel’s Ma Mère l’Oye.) According to René Chalupt, a contemporary of Satie, the Godebski’s “famous Sunday salon on the rue d’Athènes was, for many years, the meeting place for the best artists in Paris, both foreign and Parisian.”6

The poem is “a charming conceit utterly dependent for its effect on the confusion of like-sounding words [. . . ]”7

Dis-moi, Daphénéo, quel est donc cet arbre

Dont les fruits sont des oiseaux qui pleurent?

Cet arbre, Chrysaline, est un oisetier.

Ah! Je croyais que les noisetiers

Donnaient des noisettes, Daphénéo.

Oui, Chrysaline, les noisetiers donnent des noisettes,

Mais les oisetiers donnent des oiseaux qui pleurent.

Ah!...

Tell me, Daphénéo, what is that tree

The fruits of which are birds that cry?

That tree, Chrysaline, is a bird-tree.

Ah! I thought hazelnut-trees

Gave hazelnuts, Daphénéo.

Yes, Chrysaline, hazelnut-trees give hazelnuts,

But bird-trees give birds that cry.

Ah!...

The key words of this sound-play are oiseaux, oisetiers, noisettes, noisetiers, (which, unfortunately, do not preserve the same sonic connections when translated into English (birds, bird-trees, hazelnuts, hazelnut trees).

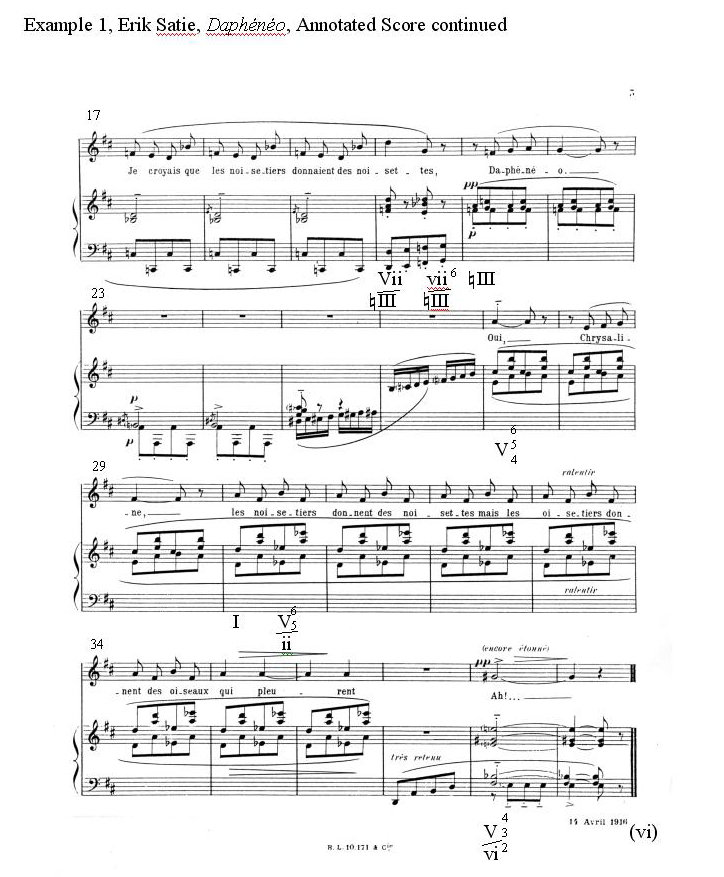

Form

The form of the song is fairly simple (Example 2). Sections and sub-sections are generally constructed in units of two, four, and eight measures. However, the two main sections, A and A’, are so contrived as to comprise ten measures: A is subdivided 4+4+2, while A’ exhibits a more irregular subdivision of 3+7 (certainly more irregular in the context of this composition). The song concludes, in a rather surprising manner, with an odd three-measure unit (which, as we will see reflects the unsettling nature of both text and harmony at this point). This three-measure unit is prepared both in section C as well as the first subdivision of A’. One might see the introduction of the three-measure subdivision in C as the catalyst for the transformation of the more typical two- and four-measure units of A into the irregular three- and seven-measure units of A’, resulting in a destabilization of A upon its return. As we will see, this resonates with the text in section C and prepares the listener for the ending, which seems to destabilize the entire song in numerous ways.

Example 2, Dapheneo, Form

Rhythm

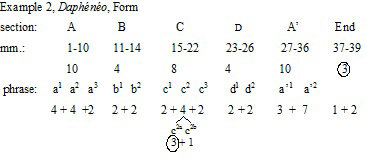

According to Robert Orledge: “First and foremost [Satie] was a man of ideas who questioned every aspect of inherited nineteenth-century tradition and rejected its conceptions of Romantic expressiveness and thematic development.”8 More specifically, during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries Satie explored “the significance of a flat, repetitive, and uninflected surface, freed of the personal expression engendered by any organic interaction with materials.”9 He achieved such a surface primarily through his pervasive use of the ostinato. This device enabled him to create what Robert Morgan has described as a “mosaic-like structure, in which various more or less ‘fixed’ musical units are combined into apparently random successions with no strictly logical connections among them. . . ”10 Indeed, throughout his career, the ostinato provided just such a “fixed” musical unit for Satie.

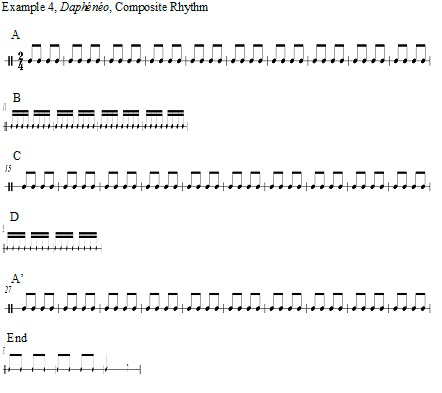

Satie’s use of ostinati in Daphénéo is indeed pervasive (Example 3). All but eight of the thirty-nine measures in the song contain an ostinato in at least one instrumental part and on three occasions we find ostinati in both piano and voice parts simultaneously (a2, c2a and a’2). As revealed in its composite rhythm (Example 4), the degree of rhythmic regularity and repetition that saturates the song is quite striking, and reminiscent of the work of such later composers as Steve Reich and Philip Glass. This composite rhythm reveals quite vividly the block-like organization noted by Morgan. It also underscores the noticeably non-progressive temporal design of the song, for the rhythmic formations within each section are quite static. Thus, in terms of rhythm, one experiences little sense of change or development and, therefore, little sense of movement or growth. Rhythmic patterms are chosen more to fill time rather than evolve through time.

Example 3, Dapheneo, Repetitive and Non-Repetitive Rhythmic Patterns

Example 4, Dapheneo, Composite Rhythm

The composite rhythm chart also clearly shows that there are three main sections in the song, A, C and A’, which are equal in duration: ten measures of continuous eighth notes. Of the other sections, two, B and D, are filled with continuous streams of sixteenth notes, while in the final section Satie returns to continuous eighth notes through its first two measures before finally coming to rest on a dotted quarter in the last measure of the piece. Moreover, B and D become progressively shorter. Thus, not only are these intervening sections characterized by shorter note values, but also by a progressive reduction in total duration. Perhaps this is intended to underscore the unstable harmonic nature of these sections. The transitory nature of each of these two sections is reflected in both their speed of pulsation and brevity.

Harmony

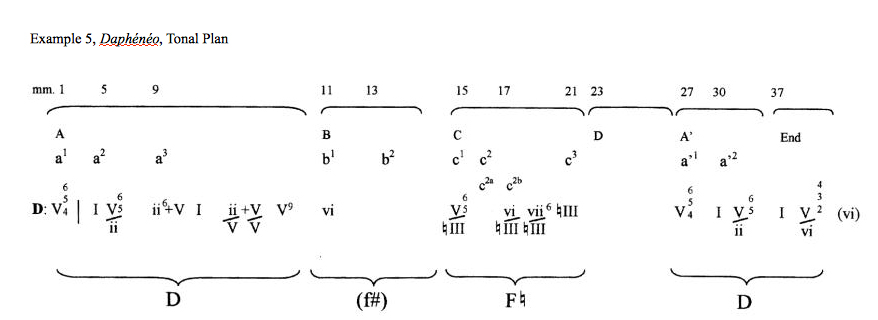

The song is in D major, but it projects an overall harmonic evolution from D to F major (not F#), and then back to D (Example 1, Example 5). The music touches upon f# minor (section B, mm. 13-14), but the real point of tonal contrast is the strong cadence on F natural in measure 21. This engenders a play of major and minor tonalities: the mediant triad of D major is, of course, f# minor, for which Satie substitutes F major. Of course, the succession of a D based tonality followed by an F natural key center suggests a possibly deeper unfolding of a d minor triad. As we will see, all of this confusion of mode (D major vs. D minor; f# minor vs. F Major) reflects the confusion engendered by the unique word-play in the text.

Example 5, Dapheneo, Tonal Plan

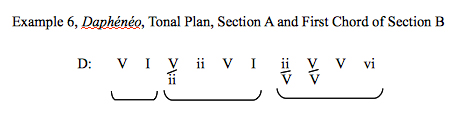

Section A and the initial chord of section B project a succession of very straightforward harmonic progressions in D major (Example 6). However, in several ways, Satie thwarts their ability to clearly establish and reinforce this tonality. For example, the initial V is a V9 placed in second inversion (Example 1 and Example 5.). Its dissonance is completely unprepared—unlike music of the common practice, where the 9th in an inverted dominant 9th chord is typically the result of voice leading (anticipation or suspension). Moreover, this 9th chord is presented without its 7th (which appears only once as a neighbor note in the vocal part in measure 3).11

Example 6, Dapheneo, Tonal Plan, Section A and First Chord of Section B

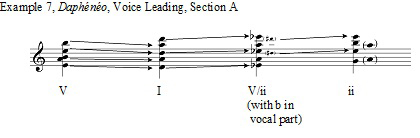

Between the V, I, V/ii and ii chords, we encounter very weak voice leading, especially in the piano part and, thus, are denied any strong sense of harmonic motion (Example 7). Indeed, throughout this passage there is no true functional voice leading. For example, there are numerous parallel octaves (between successive Es, Ds and Ebs (D#s). This draws attention to the chromaticism between the I and V/ii chords. In addition, the 7th of the secondary dominant chord in the second half of each of measures 5-8 remains unresolved. Finally, the full cadence that occurs at the end of section A (m. 9) occurs on the last eighth note of the measure. Though some may argue that Satie simply was not well versed in traditional voice leading—which may indeed have been true in his early years—he did in fact enroll in the Scola Cantorum in Paris late in life. He graduated with honors in 1908 with a Diploma in Counterpoint, his teachers having included a number of distinguished composers and scholars of the day such as Vincent d’Indy, Auguste Sérieyx and Albert Roussel!12 It seems clear that in works such as Daphénéo, composed eight years after his graduation from the Scola Cantorum, he knew exactly what he was doing and was deliberately trying to negate the power of traditional voice leading to link harmonies and push them forward toward a cadence.

Example 7, Dapheneo, Voice Leading, Section A

Perhaps most striking, however, is the way that chords are grouped together throughout the section. In the second phrase of (mm. 5-8), I and V/ii are bound together within a repeating ostinato pattern. These chords have no clear harmonic connection to one another (obviously the V/ii would normally be linked to ii). Consequently, the passage tends to highlight the chromaticism that arises when these two chords are linked to one another (especially through he aforementioned projection of parallel octaves between successive Ds and Ebs, which are reiterated over and over on strong beats), rather than any harmonic connection between chords. In this phrase we seem to lose any sense of D major, indeed any sense of tonality itself.

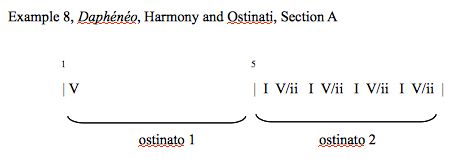

The obvious cadence of the V chord of the first phrase to the I at the start of the second is immediately negated by the many factors outlined above: the dissonant inversion of the V9, the excessive parallelism in the voice leading and, most importantly, the juxtaposition of I with V/ii rather than, as one might expect V with I and V/ii with ii. As such, the harmonic progressions of the passage do not so much evolve toward one another as merely follow one another, with little sense of inevitability as would typically associate with such straightforward progressions. Indeed, everything about the passage seems to negate any sense of the forward thrust characteristic of tonal motion. Harmony, in part, provides the means to fill up blocks of time, albeit with uniquely identifying sonorous qualities. Of course, the aforementioned ostinati support this treatment of harmony. The ostinati make each phrase static and non-generative, further stripping the underlying harmonic progressions of any sense of movement. The first ostinato of the composition (piano, phrase 1) articulates the V9 chord while the second ostinato binds the I and V/ii chords into one, harmonically incompatible unit (Example 8). These first two blocks sever normal tonal connections and replace them with juxtapositions of seemingly unrelated chords!

Example 8, Dapheneo, Harmony and Ostinati, Section A

The final cadence of section A is itself further compromised by the presence of the note A in measure 9, superimposing V onto ii (Example 1 and Example 5). One could see the chord on the downbeat of measure 9 simply as a V9 in third inversion, but this would deny the sense of resolution of the previous V/ii and the strong connection between the repeated D#s of the previous measures and the Es of measure 9. I believe the situation is more complex and we hear ii and V superimposed upon one another at this moment.

In the final measures of A (mm. 9-10) potentially strong cadential points arrive at very weak rhythmic points (I on the last eighth note of measure 9, and V9 on the last eighth note of measure 10). Furthermore, these points are subsumed within the sequential patterns that characterize these measures, ultimately thwarting any sense of finality.

Section B begins with a resolution of the V9 that concluded section A to a deceptive vi (m. 11, Example 1). The passage seems to move to a dominant (V/vi) in its final measures but, once again, its rhythmic placement on the last eighth note of each measure robs the passage of a clear sense of finality or goal (mm. 13 and 14).

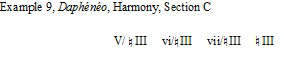

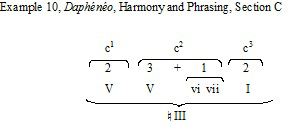

Section C projects the most straightforward harmonic progression of the song, though, ironically, in a harmonic region far from the home key of D major, that of F major (Example 9). It is also the section in which harmonic motion is most clearly supported by rhythm; for the first time in the song, a cadence falls on a downbeat (m. 21, Example 1). Until this moment in the song, Satie’s block like design tended to neutralize tonal attractions and sever their connections. In section C, however, this same block-like design seems to reinforce harmonic motion. In the first phrase of C, the dominant of F is sustained by its own ostinato. In the second phrase, the first three measures continue this support of the dominant; then in the final measure of the phrase we hear in rapid succession a deceptive motion to VI of F then vii of F and finally in the last phrase of the section a clear resolution to F which is also sustained for two measures with an ostinato (Example 10).

Example 9, Dapheneo, Harmony, Section C

Example 10, Dapheneo, Harmony and Phrasing, Section C

Section D, in contrast, constitutes the most harmonically ambiguous passage of the piece. In measures 23-24 we find a continuation of the octave eighth notes heard throughout section C, though now on A, the third of the previous F major chord. This A prepares us for the subsequent return of D major four measures later (section A’, m. 27). Superimposed on top of this A is the major third B-D#.These two tones anticipate the chord sounded on the downbeat of measure 25, which closely resembles an augmented 6th chord (either a German 6th with B rather than Bb, or an Italian 6th with one added tone). The typical German 6th in D major would contain the augmented 6th,Bb-D#, which would then resolve to octave As, the dominant of D. Satie’s chord, however, contains the augmented 6th Eb-C# and so pulls directly to octave Ds. As such, it still seems to point back to D, though, once again, as one might expect, in a rather irregular manner. However, Satie does not give us these Ds at this point; in the forthcoming reprise of the A section we are greeted first with the return of the dominant of D before the tonic is heard. Thus, the song lurches toward a return of D major in a very disjointed manner, in which local connections are never quite what are expected.

This quasi-augmented 6th chord is superimposed upon a fragment of a chromatic scale that fills in the space of the chord with half steps, seeming to wipe away all its harmonic implications—regular or otherwise.13 This chromatic scale turns into a b minor scale in the following measure (measure 26), somewhat reminiscent of section B where Satie took us to vi of D major (b minor chord), the result of a deceptive motion at the end of section A (and which, we shall see, also anticipates the unresolved V/vi chord at the end of the entire song). Of course, this turn of events could explain the presence of the B natural in the quasi-German 6th chord rather than the expected Bb.

Section A’ constitutes a varied reprise of A. A’ begins, as before, with the inverted V9, though it is curious that, at this point, the second inversion dominant 9th feels more stable. It is a testament to Satie’s ability to disrupt our normal tonal expectations that the dominant seems to be the goal of this reprise rather than a lead in to the subsequent tonic. As noted earlier, the phrasing of A’ is less square than A. Unlike A, section A’ consists of only two phrases, a1 and a2, which correspond to the first two four-measure phrases of section A. However, here a1 is truncated from four measures to three while a2 is expanded from four measures to seven. Such irregular phrase lengths add to the sense of instability conveyed by this passage.

The end consists of an open fifth D-A, signaling, however briefly, a resolution of the V9 chord that opened section A’, followed by a minor third B-D, perhaps suggesting an incomplete vi. This is followed by a completely unresolved third inversion dominant 9th chord of vi; its 7th, which sounds so prominently in the bass, is tripled, while its unresolved 9th is equally exposed as it is held by the singer. It is curious, however, that the A# of this chord is spelled as Bb. Perhaps Satie is trying to show that the chord contains an augmented 6th G#-Bb, which, as mentioned above, would be present in a true German 6th chord of D major. Clearly, however, Satie is trying to leave the composition sounding open and unresolved at its conclusion.

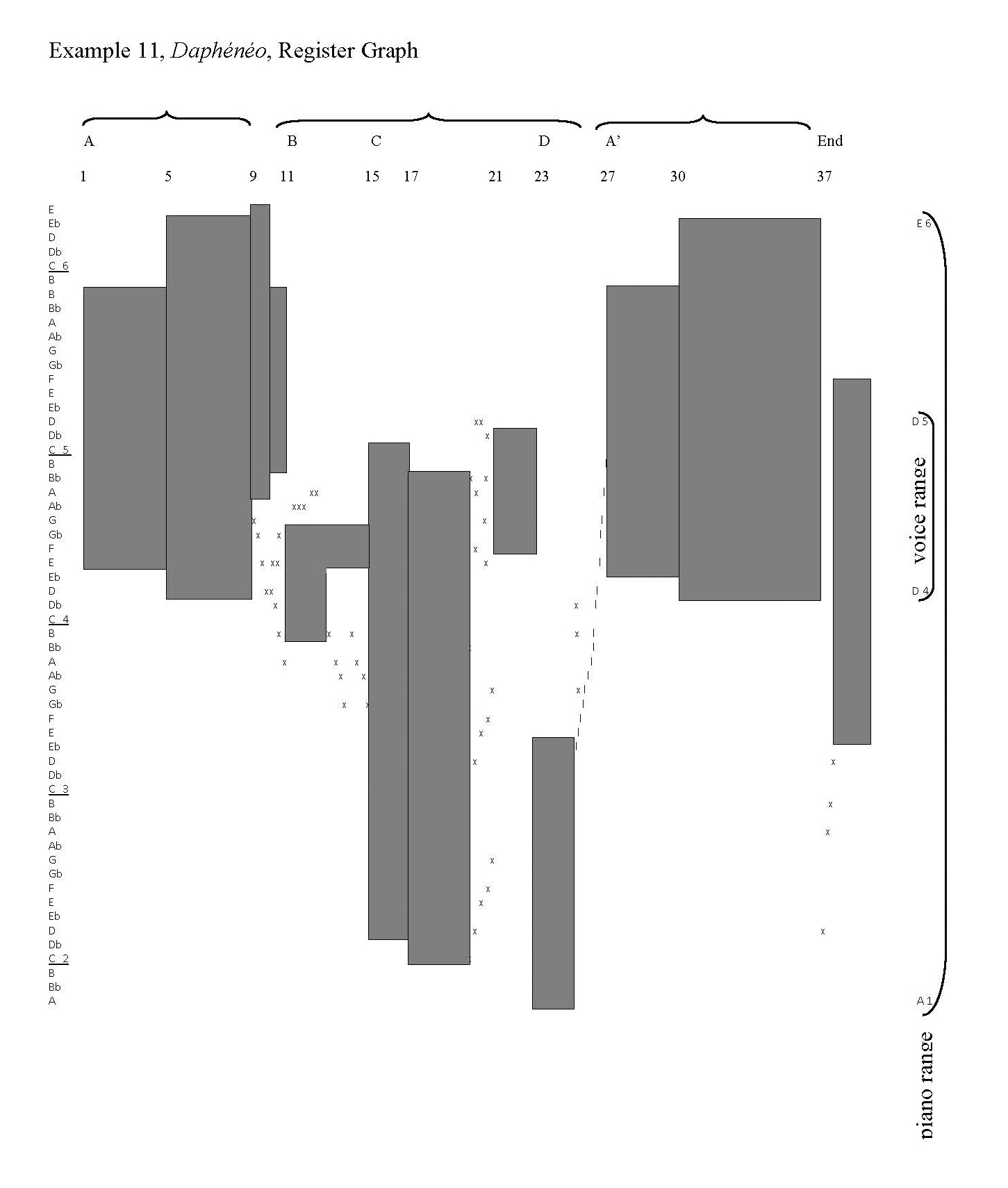

Register

Daphénéo exhibits a very sophisticated spatial design (Example 11; in this example all regions blocked off in gray represent sections and phrases of the song that are filled with ostinati). Clearly sections A and A’ occupy distinctly higher spatial regions than sections B, C, and D. Through this inverted arch-shaped motion Satie differentiates the sections that are in D major from those that veer off course tonally. It seems clear, too, that the block-like design engendered by the extensive use of ostinati is enhanced by this spatial design.

Example 11, Dapheneo, Register Graph

Text

The text is distributed throughout the song in the following way:

A a1 Dis-moi, Daphénéo,

a2 quel est donc cet arbre

Dont les fruits sont des oiseaux qui pleu-

a3 -rent?

Cet arbre,

B b1 Chrysaline, est un

b2 oisetier.

C c1 Ah!

c2 Je croyais que les noisetiers

Donnaient des noisettes,

c3 Daphénéo.

A’ a’1Oui, Chrysaline,

a’2les noisetiers donnent des noisettes,

Mais les oisetiers donnent des oiseaux qui pleurent.

End Ah!...

Satie presents the text through a simple vocal line devoid of excessive motion, a fine example of his ‘uninflected surface.’ This is most obvious in passages like the second phrase of section A, in which both the piano and voice repeat the same material over and over with no attempt to underscore the meaning of the words or dramatize them in any way. Here, Satie distances the text from its musical support, draining each moment of emotional resonance and motivation.

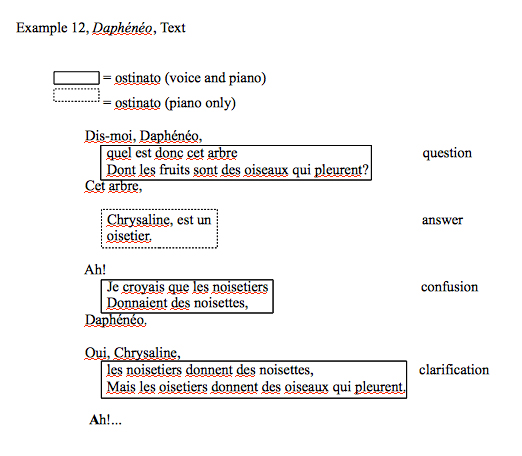

The text is essentially a dialog between two girls, Daphénéo and Chrysaline. This dialog contains four key moments consisting in turn of a question, an answer, some resulting confusion and a final clarification (Example 12). Each of these four moments is articulated musically with an ostinato, either in the piano and vocal parts together (question, confusion and clarification) or in the piano part alone (answer). Each of these moments carries the argument of the text forward—a simple confusion of meaning based upon its word play. The ostinati rob each moment in this dialog of any intensity. They become flat, uninflected, non-goal oriented passages, not unlike some late twentieth-century poetry or prose in which language is stripped of its dramatic resonance altogether.14

Example 12, Dapheneo, Text

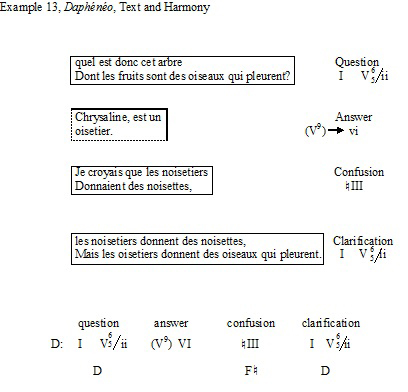

Harmony also underscores this confusion (Example 13). Satie outlines a minor third D-F within a piece in D major and the surprising appearance of F major coincides precisely where the confusion is created by the word play of oisetiers and noisetiers. Moreover, we sense that the answer to the initial question (Chrysaline, est un oisetier) does not quite ring true as it is set to the deceptive vi. The final word of the song (Ah!) is set to music that pulls us away from the central tonality (mm. 38-39), leaving the piece open and unresolved at its conclusion, perhaps a reference back to the initial answer offered by Daphénéo. In the end, we are left with a playful sense that the general confusion may not be clarified after all.

Example 13, Dapheneo, Text and Harmony

Alban Berg, Piano Sonata (1907-08)

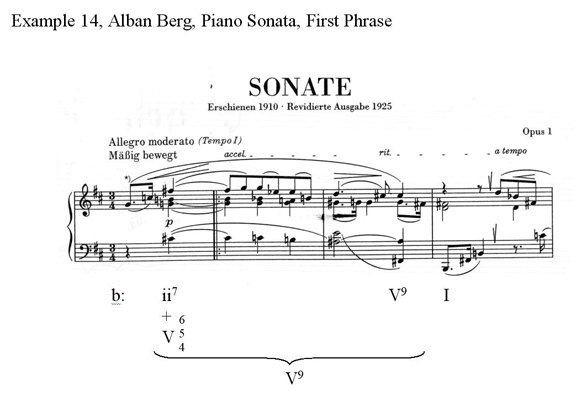

A comparison of Daphénéo with an oft-discussed contemporaneous piece, the Piano Sonata of Alban Berg, will highlight the many distinctive qualities of Satie’s style as well as the branch of Modernism that his style exemplifies. It is undoubtedly coincidental that both Satie’s song and Berg’s sonata begin with a V9 in second inversion. However, the fact that they each chose to initiate their compositions with the same material affords an opportunity to highlight the differences in their compositional approaches, as well as that of the Modernist traditions that their styles embody.

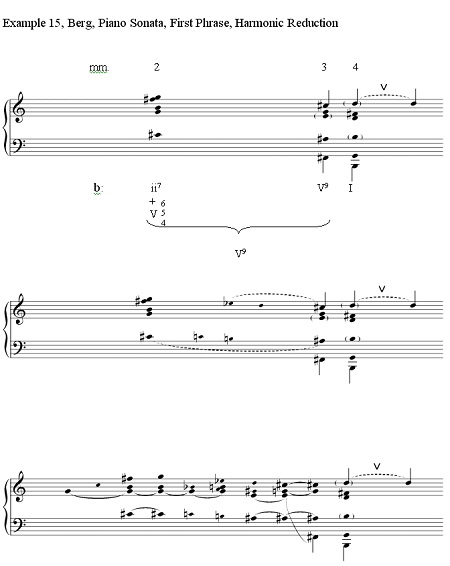

A cursory examination of the first phrase of Berg’s sonata clearly shows the underlying evolution of the harmony and voice leading of the passage (Examples 14 and 15).15 The substance of the first phrase is the very formation of a V9 chord, which, when it finally crystallizes, closes immediately to I. The first chord is clearly a conflation of ii7 and V9 in second inversion. It has been argued that the sonata opens solely with a ii7, but this strikes me as an oversimplification that misses the sense of an emerging tonality that shapes this phrase.16 In this initial conflation of ii7 and V9 each chord is compromised in some significant way. For example, the F# in the upper voice is stronger both in terms of rhythmic placement and duration than the G to which it would supposedly resolve if viewed merely as an appoggiatura to that note. Indeed, by the time this G finally receives some rhythmic weight (when it appears on the second beat of measure 2) the C# and B of the ii7 chord already have been replaced by C and Bb. The presence of V9 in the first measure is clarified in another significant way. The C# in measure 2 passes down chromatically to A# in measure 3. This A# does not then fall to F# in the bass at the end of the third measure. It simply holds through the measure. As Berg clearly shows through his slurring in that measure, the F# in the bass emerges from the E on the down-beat of the third measure. Thus, the initial C# of the composition seems to be part of an inner voice moving from the fifth of the V chord (C#) to the third of that chord (A#), though this is only revealed as the phrase approaches its cadence.

Example 14, Alban Berg, Piano Sonata, First Phrase

Example 15, Berg, Piano Sonata, First Phrase, Harmonic Reduction

I dwell on this point because this conflation of ii7 and V9 at the outset of this sonata is, in my view, very important. Within the highly chromatic context of the opening measures of this sonata ii7 alone would not strongly point us toward I, especially given the prominence of F# in the melodic line. However, the conflation of ii7 and V9 (due to the prominence of that very same F#), while still unfocused for the reasons outlined above, starts to point the listener toward b minor a bit more. 17 Gradually, the tonal basis for the passage becomes clear as these two chords slowly start to untangle themselves from one another and finally achieve a cadence. In a sense, at the moment of cadence the listener discovers the inherent tonality of the passage. It is only by the first cadence in measure 4 that we realize that the means for making that cadence were present in the preceding materials and were gradually coalescing in a way in which their potential tonal functions could be realized. One can think of few more vivid examples of the immanence of a musical language within an unfolding composition than the opening of this sonata.

The first phrase of this sonata presents a wonderful example of organic evolution, at least with respect to its emerging sense of tonality. The b cadence in measure 4 is literally engendered by the preceding movement of pitches as they shift from a rather unfocused sense of tonal center toward a more defined alignment of tones which can be truly understood as meaningful in a tonal sense, defining b minor clearly as a functioning musical language. Here, tonality does not exist until the possibility of cadence, immanent within the pitches themselves, is revealed and then achieved. Thus, in this piece, V does not exist a priori. It must be formed, as if from nothing and its formation constitutes the form (shape) of the phrase—makes the phrase, literally; and the process of forming the phrase is the process of forming its language.18 This is its organic nature.

In Satie’s song, the initial V chord exists unchanged from the start and is used to fill a specified block of time. Its formation does not engender that block of time. Rather, it constitutes pre-existing material used to articulate a predetermined period of time. (Much like a color fills a tile in a mosaic; the color does not create the shape of the tile, the shape pre-exists it.) In the second phrase of Daphénéo I and V/ii are blocked together, thwarting, as we have discussed earlier, their natural connections to other chords around them. These two chords, which do not themselves have any strong tonal connections to one another, are tied together in a seemingly arbitrary way (giving measures 5-8 an almost non-tonal quality when taken out of context of the surrounding measures). Harmonies in Satie are presented, but do not evolve, nor do they lead to one another. Units of time (phrases, sections) are not formed by the evolution of the harmonic material contained within them, they exist separate from those materials and are merely containers for them. In this sense, then, Satie’s compositional style is not organic.

Conclusion

Satie’s style clearly represents a significant break with nineteenth-century European practice, both in terms of its refutation of the power of directed motion inherent in common practice tonality, and the sense of directed rhythmic motion that supported that practice. Through his systematic negation of the connective tissue of common practice voice leading, his use of unexpected, tonally ambiguous and unresolved dissonances, as well as the non-propulsive rhythmic stasis produced by his pervasive use of ostinati, Satie’s music projects a sense of non-directionality (or perhaps, multi-directionality) which leads inevitably to a displacement of the listener’s expectations as conditioned by traditional compositional practice, and ultimately, as sense of non-inevitability, arbitrariness, indeterminacy. As such, Satie’s music stands in opposition to the organic conception of form which Berg and his like-minded contemporaries inherited from nineteenth-century practice. Satie’s music epitomized an important branch of modernism that continues well into the twenty-first-century, and set the stage for the creative breakthroughs in the middle of the twentieth-century through the so-called “Postmodernism“ of the late twentieth and early twenty-first-centuries. Satie and his successors followed a special path through the Modern era, which paralleled that of composers such as Schoenberg and Berg whose work epitomized an extension of the organicism of the Romantic era into the twentieth-century. It is only through an understanding of the complementary nature of these two branches of Modernism that we can finally begin to formulate a comprehensive view of the music of our time.

Bibliography

Aldwell, Edward and Carl Schachter. Harmony and Voice Leading. Belmont, CA: Schirmer, 2003.

Berg, Alban. Piano Sonata, Op. 1. Munich: Henle Verlag, 2006.

Cage, John. “Erik Satie.” In Silence. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1974.

DeLio, Thomas. The Amores of John Cage. Hillsdale, NY: Pendragon, 2010.

___. “Language and Form in an Early Atonal Composition: Schoenberg's Op. 19 No. 2.” The Indiana Theory Review 15, no. 2 (1994): 17‒20.

Gillmor, Alan M. Erik Satie. New York: W. W. Norton, 1988.

Headlam, David. The Music of Alban Berg. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1996.

Jarman, Douglas. The Music of Alban Berg. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1979.

Morgan, Robert P. Twentieth Century Music: A History of Musical Style in Modern Europe and America. New York: W. W. Norton, 1991.

Orledge, Robert. Satie Remembered. London: Faber and Faber, 1995.

Perloff, Marjorie. The Poetics of Indeterminacy: Rimbaud to Cage. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1983.

Rameau, Jean-Philippe. Treatise on Harmony. New York: Dover Publications, 1971.

Satie, Erik. “Daphénéo.” From Trois Mélodies. Paris: Editions Salabert, 1917.

Schmalfeldt, Janet. “Berg’s Path to Atonality: The Piano Sonata, Op. 1.” In Alban Berg: Historical and Analytical Perspectives. Edited by Robert P. Morgan and David Gable/ Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991.

Shattuck, Roger. The Banquet Years. NY: Vintage Books, 1968.

Sheldon, David A. “The Ninth Chord in German Theory.” Journal of Music Theory 26, no. 1 (Spring 1982): 61-100.

Webern, Anton. The Path to the New Music. Edited by Willi Reich, translated by Leo Black. Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania: Theodore Presser Co., in Association with Universal Edition. Reprinted London: Universal Edition, 1975.

Endnotes

1In my book, The Amores of John Cage, I outlined these two branches of the Modern era, discussed their evolution, and noted the long history of criticism supporting this view.

3Cage, “Erik Satie,” in Silence, 76‒82.

5Berg, Piano Sonata, Op. 1. This view of the organic nature of the compositional process was established by Anton Webern, who, in his lectures The Path to the New Music argued that the music of his mentor and teacher Schoenberg and his students led to an intensification of organic unity in composition. Webern, The Path to the New Music, ed. Willi Reich, trans. Leo Black.

6Orledge, Satie Remembered, 145.

9DeLio, The Amores of John Cage, 7.

10Morgan, Twentieth Century Music, 52.

11See Adwell and Schachter, Harmony and Voice Leading, 477‒78. Also see Sheldon, “The Ninth Chord in German Theory” for an excellent summary of the treatment of the ninth chord by German theorists in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. In contrast see Jean-Philippe Rameau’s consideration of the ninth chord in his famous Treatise on Harmony.

12See Gillmor, Erik Satie, 134‒139 for an excellent discussion of Satie’s initial shortcomings and later education at the Scola Cantorum. (I disagree thoroughly with his opinion of Satie’s ability as an orchestrator; there are numerous instances in his late ballets of a very masterful, though unorthodox treatment of orchestration).

13In his book The Banquet Years, Roger Shattuck notes that, in Satie’s Socrate, after a modulation Satie often “wipes the slate clean with a scalewise passage…and starts again.” Shattuck, The Banquet Years, 164.

14For a brilliant examination of this branch of twentieth-century literature see Perloff, The Poetics of Indeterminacy.

15For several analytical views of the Berg Sonata see Schmalfeldt, “Berg’s Path to Atonality”; Headlam, The Music of Alban Berg; Jarman, The Music of Alban Berg.

16See, for example, Schmalfeldt, 91‒92.

17The more simplistic view of the opening as a ii-V-I progression leads Janet Schmalfeldt to the rather contradictory notion that “…the primary melodic tone of the work, 5, enters as an appoggiatura…”, graphed as an unsupported open-head F#. See Example 2c in Schmalfeldt, “Berg’s Path to Atonality,” 92. The F# is melodically just as strong as the subsequent G to which it supposedly “resolves.” I see this as a chord that telescopes ii7 and V9.

18Thomas DeLio, “Language and Form in an Early Atonal Composition: Schoenberg's Op. 19 No. 2," 17‒20.