Introduction

Many teachers of music theory are intrigued by the idea of including popular music as an addition to the traditional music already taught in theory classes. Music familiar to students offers the opportunity to demonstrate a connection between academic material and music the student has already internalized. Educational theorists have long touted the idea, originally proposed by Lev Vygotsky (1987) and elaborated upon by many others, of scaffolding: working from what the student already knows toward unfamiliar material.

The teacher must, however, ensure that the music presented, if not approaching the level of Bach, Beethoven, and Mozart, at least demonstrates an acceptable level of musicianship. Scholars of popular music have indicated that the music of the Beatles does have worth that transcends their particular moment in musical history.1 In fact, the Music Educators National Conference (MENC) has indicated the Beatles song “Yesterday” is on the list of songs that everyone should know (1995). Although the Beatles themselves were not classically trained, their producer, Sir George Martin, who did have classical training, profoundly influenced the group. The influence of Martin is evident on songs such as “Lady Madonna,” “She’s Leaving Home,” and the avant-garde “I am the Walrus.”

Another hurdle in the use of popular music for instruction is inexperience of professors with the idiom. By the time the academic professional has time to reflect thoroughly on the importance of a particular genre, often the winds of popular taste have shifted so much that the music is passé. With more recent releases, the students often know more about the music than the instructor, so the teacher lacks credibility when teaching modern popular music. Beatles songs are an excellent solution to this dilemma. The songs have existed long enough to be thoroughly studied; yet, they are still known and accepted by younger people. Beatles songs transcend their history, as different generations play the recordings for each other, just as classical music transcends its place in history.

The Music

Four Beatles songs can serve as examples for elements of music theory traditionally taught using classical music or contrived material. First, the song “Her Majesty” includes a straightforward use of secondary dominants. Modulation to closely related keys is evident in the songs “I Want to Hold Your Hand” and “Yesterday.” Increasing complexity and modulation to foreign keys exist in the song “Here, There and Everywhere.” In using this material, one would assume that the student has an understanding of diatonic chords and their function. In this paper, analysis of the chord structure includes the text of the song as a reference, with chords written in modern notation above the music and Roman numeral notation below the music. Transcriptions of the pieces may differ from published versions due to either disagreements between transcribers or simplification of material in order to demonstrate better the modulation concepts.

Secondary Dominants: “Her Majesty”

Teaching the concept of modulation often begins with a demonstration of the use of secondary dominants—dominant seventh chords built on scale degrees other than the fifth—that serve to enhance the presence of the chord that follows. The Beatles song “Her Majesty,” a simple ditty almost lost as the coda to the Abbey Road album, is an excellent source of secondary dominants used in ways that are common to all types of music.

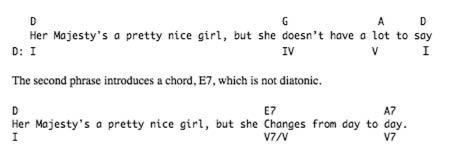

The first phrase of the song is rudimentary, establishing a D major tonality.

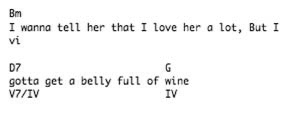

The E7 enhances the dominant A7 chord that follows. Since E7 would be the dominant in the key of A, the E7 chord “tonicizes” the A7 with an aural reference to an authentic cadence in the key of A. Instead of notating the chord as II7, the symbol V/V (five of five) demonstrates this secondary dominant function. The next phrase begins on the submediant B minor in the key of D as substitution for I. The third chord in the phrase then introduces another secondary dominant, the D7 V/IV (five of four), which enhances the subdominant chord that follows. Since the D7 would be the dominant in the key of G, the chord is notated as V7/IV (G is IV in the key of D).

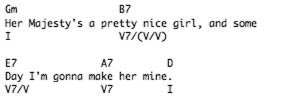

In the next line, after the pleasing chromatic harmony of G minor, the song introduces a chain of secondary dominants.

An alternative harmonic analysis redefines the function of B7.

However, since the term V7/(V/V) is awkward, and since these chains of dominants could continue {e.g. V/[V/(V/V)] . . . }, the term V/ii is simpler to notate. This use of secondary dominants highlights the chord that follows and produces a momentary aural sensation of a change in tonality. The song “Her Majesty” provides multiple representations of secondary dominants used in the most common ways—V/V, V/IV, and V7/(V/V).

Modulation to Closely Related Keys: “I Want to Hold Your Hand”

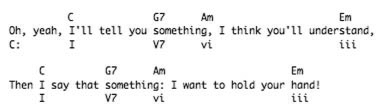

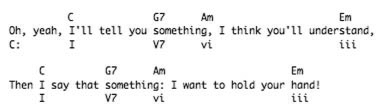

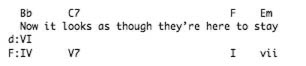

“I Want to Hold Your Hand” is an example of an uncomplicated song that modulates to the subdominant tonality in its bridge. The chord progression begins simply, as was typical of the popular music of the early Sixties.

The chorus is even more rudimentary, featuring a IV-V7-I progression.

The chorus is even more rudimentary, featuring a IV-V7-I progression.

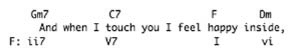

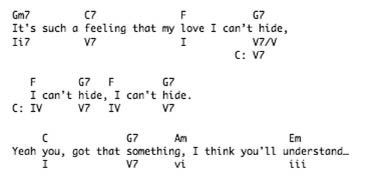

However, after the second verse, the C chord has two functions. The tonic chord serves as the dominant in the new tonality of F major, or the classic “common chord” modulation. The addition of the G minor seventh chord and the C dominant seventh chord clearly indicates the new tonality.

After continuing for a short time in F, the songwriter uses a G7 chord to modulate back to the original key.

By modulating back to the original key, the song contains elements of closed forms in classical music that start in a tonic key, modulate to a closely related tonality, and then modulate back to the original key center. Because this example has a simple set of chord changes, the process of modulation is more manifest than more complex examples. Just as when teaching modulation using classical examples, the instructor often begins with simple forms (such as binary and ternary); this early song is a demonstration of a very simple popular form that happens to modulate.

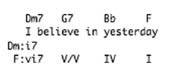

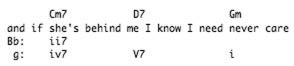

Modulation to the Relative Minor: “Yesterday”

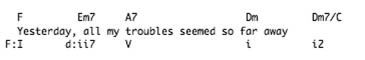

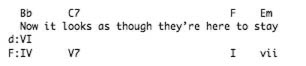

While a change to the key of the dominant is the most widely-used modulation in classical music before 1900 in a major key, in popular music a modulation to the relative minor is more likely. This change modulates to a key center that is closely related in that the new key contains the same key signature as the original. The Beatles song “Yesterday” can be an example of such a modulation. The chords of “Yesterday” move freely between the major and relative minor. Some theorists who study popular music do not analyze this movement as a modulation, but for teaching purposes, the following analysis does. The piece begins by establishing the key of F major with a series of tonic chords. However, the chords that follow, E minor seventh and A dominant seventh, are not diatonic to the key of F. Because the chord following A7 is a D minor chord, the piece seems to modulate to D minor at this point.

The possible modulation to D minor is enhanced—the music enhanced, not the analysis—by the presence of the E minor seventh chord before the A7, because in popular and jazz music, often a key change contains the presence of the supertonic followed by the dominant (ii-V). Thus, a cadence in the new key (ii-V7-i) supports the contention that a change of key center exists. In the key of D minor, however, one would expect the supertonic chord to be a half-diminished chord (Em7b5). The composer chooses the supertonic that is borrowed from D major, no doubt because Em7 is easier to finger on the guitar than Em7b5, and it serves the same function.

The key center does not stay in the new key for a long time, as a cadence in the original major key follows with the Bb chord serving as a common chord (the submediant in D minor and the subdominant in F).

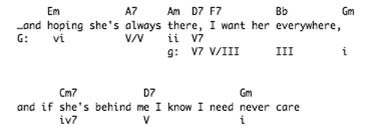

After the apparent cadence in the original key, the song seems again to modulate to d minor. One might surmise that the change back to the original relative major was not a ructural harmony at all, but simply an embellishment of the minor key. An alternate analysis might show the C7 chord as a secondary dominant:

The following phrase is problematic, because the G7 chord appears to be a secondary dominant in the original key (V/V in F), but it does not resolve to C as expected. Rather, a plagal cadence completes the phrase.

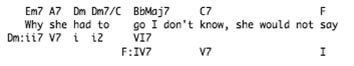

The G7 chord simply establishes a predominant harmonic status that is fulfilled by the plagal cadence rather than an authentic—a process not uncommon in classical music also. If there were any doubt as to the structural importance of the modulation to the minor tonality, one only needs to look to the bridge. The key centers alternate between the relative major and minor in each phrase, beginning in minor and modulating back to major.

“Yesterday” contains a shifting modulation between the original tonic key and its relative minor. The complexity of the Beatles’ music continuously evolved as the musicians matured from the simple pop style of their early songs such as “I Want to Hold Your Hand” to the more experimental music of the late sixties.

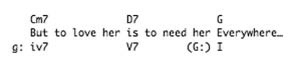

Foreign Keys: “Here, There, and Everywhere”

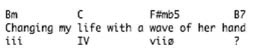

As the songwriting skills of the group matured, their songs began to venture into more complex tonal areas. Later Beatles songs, such as “Here, There, and Everywhere,” also contain of modulations to keys that are not closely related. This song first establishes the tonality of G major with a series of diatonic chords.

At the end of the second phrase a B7 chord indicates a possible secondary dominant or a change of tonality.

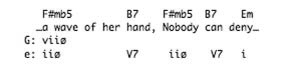

The B7 chord resolves only after a repeat of the chords F#mb5 and B7. The chord does indeed eventually resolve to the expected E minor chord. Since a string of chords now fits into the new tonality of E minor, a modulation exists using the classic iiø-V7-I progression.

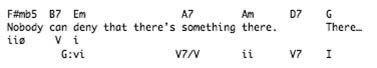

Again, the songwriter chooses the common modulation to the relative minor, as in “Yesterday.” The harmonies could be embellishing, with B7 serving as a V/vi, but since a complete cadence occurs (iiø-V-I) and the key center continues for more than a few measures, a key change is more palatable. He also again chooses to switch back to the original tonality quickly. However, the progression back to the G major is much more sophisticated than the earlier piece. An A7 chord, best analyzed as V7/V in G major, has its resolution to D7 delayed by the supertonic A minor chord. Thus the composer exploits both the strong secondary dominant function of V/V and the easily recognizable ii-V-I progression.

After a repeat of the chord changes through the second verse, the song moves to a tonality that is foreign. Instead of resolving the dominant to the expected G chord, the piece unexpectedly seems to cadence in B flat major.

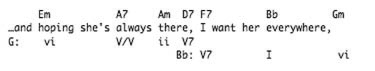

The D7 chord is troubling, because it does not seem to fit in B Flat. The next phrase could follow in the Bb tonality

but for the sake of consistency with previous analyses, this passage works better as another modulation to the tonality of the relative minor of Bb, namely G minor.

Re-analysis of the bridge in Gm reveals that the D7 is the dominant with a delayed resolution.

Since G minor is the parallel minor of G, the choice of G minor makes the mode change back to the original key quite smooth.

The composer uses the B flat tonality as a bridge to reach the parallel minor. Just as in classical music, the parallel minor is the most accessible of the foreign keys for modulation. The number of similar tones between G major and G minor make this choice of modulation pleasing to the ear, even though the scales have three notes which are different. Once again, a Beatles song can demonstrate modulation concepts common to all styles of music.

Conclusion

Beatles songs may serve as an introduction to the study of modulation. Clearly, the songwriters did not have Roman numeral analysis in mind when composing, but wrote progression that sounded good. Well-written music often obeys the conventions of traditional harmony because the rules of composition developed by classical composers came about in response to the aural recognition of what sounds pleasing. Popular music that follows musical traditions is extant in the culture. Certainly, many kinds of music exist which are not of the quality acceptable for the classroom. One could argue, however, that music from all periods contains examples of superior and inferior writing—the classical music has survived the test of time. Popular music will certainly suffer the same fate; most will be long forgotten, but some gems will survive and become part of the standard repertoire for study.

Discography

Lennon, John, and McCartney, Paul. “Her Majesty.” Abbey Road. Apple Records, 1969.

Lennon, John, and McCartney, Paul. “Here, There and Everywhere.” Revolver. Parlophone, 1966.

Lennon, John, and McCartney, Paul. “I am the Walrus.” The Beatles. Apple Records, 1968.

Lennon, John, and McCartney, Paul. “I Want To Hold Your Hand.” Meet the Beatles! Parlophone, 1963.

Lennon, John, and McCartney, Paul. “Lady Madonna.” Lady Madonna. Parlophone, 1968.

Lennon, John, and McCartney, Paul. “She’s Leaving Home.” Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. Parlophone, 1967.

Lennon, John, and McCartney, Paul. “Yesterday.” Help! Parlophone, 1965.

References

Beatleshistory.net. (2009). Beatles and Biographies, Beatles History, Beatles Books. Retrieved July 30, 2009 from http://www.beatles-history.net/beatles-and-biographies.html

Music Educator National Conference. (2009) Get America singing ... Again! Volume 1. Milwaukee, WI: Hal Leonard Corporation.

Vygotsky, Lev (Leon) Semyonovich (1987). Thinking and speech. In The Collected works of L. S. Vygotsky (vol. 1, pp. 39-285) (Robert W. Rieber & Aaron S Carton, Eds; Norris Minick, Trans.). New York: Plenum. (Original works published in 1934, 1960).

Endnotes

1An exhaustive review of the Beatles’ history is out of the scope of this paper. For those interested in documentation on the Beatles’ music and history, the reader is directed to the Web site http://www.beatles-history.net/beatles-and-biogrphies.html (Beatleshistory.net, 2009), which contains a long list of resources.