Japanese composer Koji Nakano, like many young Asian composers, left his native country to continue his study of music composition techniques in the Western art tradition. Although he was exposed to various kinds of Japanese traditional music throughout his childhood in Japan, it was not until much later in his studies in the United States that he began to consciously incorporate non-Western elements into his music. Nakano explains his own personal rediscovery of his native culture and how it has affected him as a composer.

When I finished my study with Louis Andriessen as the Japanese Government Overseas Study Program Artist in 2003, I went back to the University of California, San Diego to complete my Ph.D. degree. My mentor Chinary Ung told me “you seem to master one of two cups, the Western compositional techniques, but you forgot to fulfill another cup, your Asian musical heritage, to complete your total vision.” What Chinary told me was an eye opening experience. I realized that I had to start understanding and researching my own original culture and other musical cultures to fulfill the missing cup.1

Nakano realizes that many questions that concern cross-cultural borrowing must be seriously considered before integrating non-Western aesthetics into the Western art tradition. It is also not only necessary to study the music of a specific culture, but attempt to find a deeper understanding of the music by studying the various customs and spiritual meanings behind the music. Nakano believes that some elements from different musical cultures blend well, and some do not. In Time Song II, he juxtaposes culturally distinct elements with three different intentions:

- Essence of musical cultures—loosely interpreted and abstract adaptation of traditional Japanese instruments to a Western compositional language

- Coexistence of musical cultures—a layering of musical elements in a kind of counterpoint to one another, letting them interlock without losing their separate identities.

- Fusion of Musical cultures—joining two or more things together to form a new, single, and distinct entity.2

Vocal techniques and aesthetics in Time Song II

As a singer who has been trained in the bel canto tradition, I have invested many years to establish a reliable technique that not only corresponds to the aesthetic that is expected in Western opera and concert music, but also allows me to maintain healthy vocal cords. Although I am a performer of standard repertoire, I have an interest in singing music that goes beyond the traditional techniques of the Western art-music tradition. I have become interested in music that integrates these different aesthetics because of my attraction to the unconventional use of vocal timbre to produce emotional and dramatic effects. This means that I must find a way to interpret extended techniques in a way that is not harmful to my voice. I believe that with a firm technical foundation, one can explore these expressive vocal timbres.

One of the biggest challenges in this piece for me is accessing the very low notes that Nakano incorporates in the vocal part. I do train the lower register of my voice every day as I believe it is the foundation for the entire instrument. Many of Mozart’s arias, for example demand an easy chest register as well as an easy top. One may look at the role of Fiordiligi in Cosi fan tutte to discover that Mozart uses abrupt changes in registers, sometimes jumping an interval of a twelfth. One must have a secure vocal technique to be able to master this type of writing in performance.

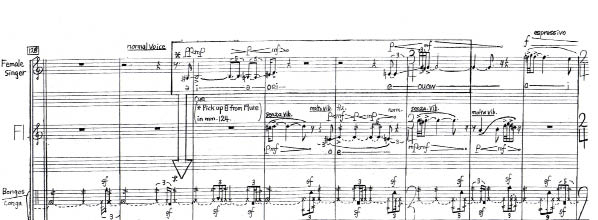

The first phrase that I sing in Time Song II is at measure 113 in the second movement. Nakano asks for a low G below middle C, moving up to the middle register A4, and then returning to the low G. My voice does not particularly shine in the low chest area. However, I believe the composer is looking for a vocal gesture or an effect rather than a beautiful resonating tone. Nakano also asks for some sprechstimme at the end of the phrase, an example of a vocal gesture where one must be careful to execute the sprechstimme with proper breath support to avoid any excess tension on the vocal cords.

Figure 1.

One of Nakano’s primary inspirations for the vocal parts of all three performers is from the vocal and instrumental techniques of the traditional Satsuma-Biwa player, as well as various folk singings and vocalisms heard in Japanese traditional music.3 Nakano describes his intent to use the essence of some of the Satsuma-Biwa techniques in which there are high and low intervallic leaps and sudden changes in vocal registers. He states that “for the very low vocal parts in particular, he was especially thinking about some characteristics from traditional singings which have various pitch inflections and ornamentations with deep and melancholic sounds from one’s chest/throat voice.”4

Nakano describes measures 129-134 in Stage III as another example of his use of essence as a compositional technique. The melody in the vocal line is based on a gagaku tuning piece but is given a new musical syntax through its primitive and guttural treatment of the voice. In addition to the essence of the gagaku melody, the bongos and conga played in these same measures give the essence of kotsutsumi drumming in Japanese Noh theatre. The essence of the gagaku melody and the essence of kotsutsumi create a co-existence of musical cultures that creates a kind of layering whereby each element retains its own identity. Fusion of musical cultures also plays a role in this particular example as the flute part presents a new layer of shakuhachi-like vibrato and pitch bends to the entire ensemble and becomes a kind of glue that binds these materials together.5

Figure 2.

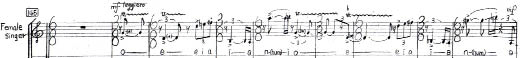

Stage III contains many dramatic contrasts for the voice as the composer often incorporates large intervallic leaps from the low chest register up into the second passaggio and high voice. The singer must be able to execute these leaps with ease and precision while moving between percussive inflections in the middle and chest register to legato melodies in the top. Nakano challenges the singer by asking her to sing a low A in chest voice, jump up to G#5, and then move to a B5 on a hum at measure 153. The singer must then return into chest voice on a low A in the same bar.

igure 3.

In addition to the specific references to the gagaku melodies and traditional narrative style of singing, Nakano asks for vocal inflections that are inspired by various types of traditional Japanese instruments. The singer is required to bend pitches and sing microtones in a style similar to what may be played on the shakuhachi or ryuuteki. In addition to these various pitch inflections, Nakano asks for sliding glissandi that often occur between large intervals. Percussive accents, as well as howling gestures that are inspired by Taiko drumming and the composer’s image of society during the Joomon period in Japan, are also incorporated into the vocal lines. The challenge for the singer is to be able to execute these contrasts of percussive accents and legato singing in a relatively short amount of time.

Figure 4.

Nakano asks for an even more dramatic type of howling beginning at measure 210: he requires the singer to do hand trills through the second passaggio. These hand trills are similar to what Luciano Berio asks for in Sequenza III—the tapping of one hand against the mouth to create a sound that mimics a traditional vocal trill by producing a rapid oscillation between two notes, and an alternation between a normal and muted sound.

Figure 5.

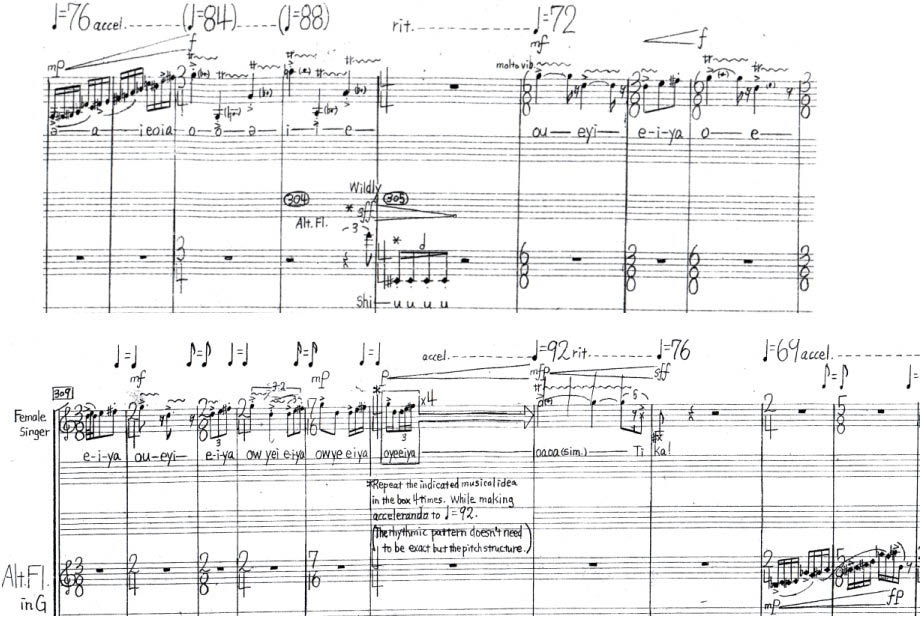

The most difficult part of the piece for the singer begins at measure 301 and continues through the end of the movement. The singer begins here on a low F3 and is required to execute a type of coloratura gesture up to G5. These next moments of the piece are very reminiscent of Western opera, as the singer is required to display a kind of vocal virtuosity that one might find in an operatic cadenza. Nakano however, asks for molto vibrato on the trills, perhaps almost to the point of an intended wobble. These vocal gestures are mirrored by the flutist, who must alternate between a frenzied character and one with a calm and lyrical disposition.

Figure 6.

The movement concludes with a final coloratura passage from the extreme bottom of the voice up to a tongue trill on high C#6. The tongue trill on such a high note presents a difficult challenge to find a way to successfully execute the effect, yet maintain an open throat in order to sing the C#. The tongue is connected to the larynx and thus must typically be in a relaxed and low position in order to sing a high note: A high larynx position is simply not conducive for singing at the top of one’s range. In order to perform a tongue trill, the tongue must vibrate on the hard palette thus the larynx is pulled to a higher position. I have found a solution to phonate on the high C# with the tongue trill, but it takes a certain amount of coordination!

Figure 7.

Spirituality and Ritual

The composer’s intention to express the spiritual side of Japanese traditional music is an essential element of this work. Performers are asked to progress through various emotional and spiritual states throughout the piece that are reminiscent of rituals associated with Japanese ceremonies. Nakano was inspired by ritual ceremonies found in (1) Shintoism, and its music that originated from ancient native music, as well as (2) Buddhism, (3) bugaku, and (4) the ritual aspect of music for taiko drum ensemble.6 It is through his experience in observing a variety of Asian traditional music that he has learned that the origin of the music has always been rooted as part of ceremonies and rituals. In addition to these spiritual influences, Nakano’s decision to use only syllables for a text rather than a text in a recognized language gives the piece a raw kind of primitivism. Time Song II was composed as Nakano’s own imaginative ritual or ceremony.

I believe that this piece has been carefully planned with regard to a confluence of Japanese and Western aesthetics. The composer has considered each musical element and how it should be incorporated through three different compositional approaches. He has also gone beyond the music and composed something that is motivated by a deeper spiritual meaning, similar to what he has experienced when observing various forms of traditional Japanese music. The piece not only contains direct quotations from this music but combines a variety of aesthetics to create something that is expressive, musical, highly evocative, and most importantly, new and innovative. It is a pleasure to perform a work that not only challenges the technical prowess of the performer, but also envelopes a truly spiritual experience and understanding towards a universal culture.

Endnotes

1Nakano, Koji. An interview conducted by Dr. Stacey Fraser via e-mail in February of 2007.

2Dr. Nakano attributes these three compositional techniques to his teacher and mentor, Professor Chinary Ung.

3All three players in Time Song II are required to sing and to play percussion in addition to their conventional roles on their respective instruments. One of Nakano’s reasons for having the percussionist and flutist sing was inspired by an analogy he draws from various forms of Japanese traditional music. “In my initial sketches of the vocalizations, I was especially focused on exploring various vocal techniques heard in traditional Japanese instrumental performance. For example, one of my musical inspirations came from the Satsuma-style Biwa player who sings and plays to tell a tragic story. I was amazed how his singing and playing interplayed continuously, intermingling, blending, and often contrasting each other. Another musical inspiration came from a recording of an Ondeko ensemble, in which several Taiko drummers play different sized Taiko drums with different rhythmic ratios. Ondeko is especially famous for its strong, energetic and virtuosic drumming with the use of thick wooden sticks. I was particularly attracted to how Taiko drummers communicate to each other by shouting random words or phrases; which functions doubly as a cue to play together as an ensemble, as well as being in the same direction and emotional stage in the music.”

4Nakano, Koji. An interview conducted by Dr. Stacey Fraser via e-mail in February of 2007.

5It is necessary to mention that there might be varying degrees of essence, coexistence and fusion and each listener may perceive these three techniques differently depending on how they hear the different layers of multi-culturalism. The lines between these three compositional techniques can perhaps become blurred.

6All over Japan, different sizes and kinds of Taiko drums are played outside as part of ritual ceremonies and festivals to swipe away evil sprits, to call for rain or to pray for a good harvest year.