Introduction: Choral Music in Estonia

The importance of song and choral music to the cultural life of countries in the Baltic States has led to an abundance of choral music and choirs with varied voicings and purpose. From casual singing at the beginning of a town meeting to the use of song as a means for revolt against the former Soviet regime, choral singing has long been a part of Estonian culture. It has been used to maintain cultural identity throughout times when other elements of life were restricted. These songs are used to pass on the traditions and stories from one generation to the next. Estonia has been invaded and occupied numerous times during its history due to its ideal location for shipping, fishing and military bases. Folk songs and national poetry were used during these times to assist people in maintaining their cultural identity while conforming to the restrictions of the occupying government. Traditional song forms, such as regilaul, became the song style for this region.1 Choral music that focused on traditional folk songs is studied in the schools as well as small community ensembles from numerous workplace groups, such as the mechanics choir. Singing is such an important part of the culture that five percent of the Estonian population currently sings in a choir and one out of ten have sung in a choir at some point.2 Song festivals provide a way for Estonians to meet and share in their national spirit under the close watch of the government. Begun in June 1869 in Tartu, these festivals allowed Estonians to gather together in song and spirit to celebrate their unity in times of oppression.3 After the Second World War, when Estonia was forcibly incorporated into the Soviet Union, governmental restrictions dictated which songs were to be performed and there were demands to have the words of many of the traditional songs changed to fit the Soviet ideology. However, songs that were not on the prescribed list of songs allowed by the government were sung spontaneously as a unifying event for the participants. Due to the large number of singers and the inability for Soviet officials to understand the Estonian text that was being sung, these spontaneous bursts of folk songs were tolerated. Through these singing events, Estonia and the other Baltic countries were able to stand up against the Soviet government in the 1990s, and this eventually led to the so-called “Singing Revolution,” which began in 1988 with the gathering of one third of the Estonian population at Tallinn’s song festival grounds to support the populist movement.4 On August 23, 1989, on the occasion of the commemoration of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, thousands of people throughout Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, gathered to join hands and sing together. This human chain spread throughout each country by people connecting hand in hand in a chain that spanned the entire region from Tallinn, Estonia to Vilnius, Lithuania, a span of nearly four hundred miles.5 Many of the songs sung at this event became inspiration for a new generation of composers in the beginning of the twentieth century, including Ester Mägi.

Ester Mägi

Ester Mägi was born in Tallinn on January 10, 1922. Her father was a craftsman and the family lived in a house that was shared by the ambassador’s quarters in the aristocratic neighborhood of Toompea. Music was a part of their everyday life. Mägi’s first memory of music was listening to the Czech ambassador play the piano as she hid behind the window, and, with the great Dom Church nearby, the children were able to hear organ music throughout the day. Although neither of her parents were musicians, she and her brother and sister were encouraged to play and study. Her older sister studied piano and after the lesson, Mägi would try to re-create what had been played during the lesson. She also attended many song festivals as a child and was fascinated by the first well-known female composer in Estonia, Miina Härma (1864-1941). Mägi is a reserved and humble person with strong personal characteristics that express themselves in her musical style. Numerous childhood events played into the development of this deep quality. She contracted scarlet fever when she was seven years old and states that she feels as if she has not been the same person since that time. Her youthful energy never returned, even after her physical symptoms subsided. She considers herself very reserved and private and has said that being a child during World War II took a big piece of happiness out of her life. She recalls the darkening of the streets at night and seeing many of her friends leave in exile or to participate in the war. A believer in astrology, she strongly stands by her place as a Capricorn, with the tendency to be persistent and ambitious. When asked to describe herself, she responded that she views herself as cool, stern and businesslike, as a person who is friendly, but not open. She has few friends, but those that she considers friends are close to her. Many are tennis partners and musicians that have help develop her compositions.6

With a strong desire for self-realization, Mägi takes great pride in being viewed as a sincere composer, whose music has to go through a creative process and be part of an inspired thought rather than just a theoretical exercise. Even in technically challenging works, there is a focus on the feelings of the soul through the process of experimentation. She regards insincere music as superficial and although it may be beautiful, it does not reach to one’s soul. She believes that her music reflects her tendency of being introverted due to the fact that it is not quickly understood and open to the listener, but rather reveals itself only through many hearings and the rehearsal process. Mägi states, “If you explain your music too much, it takes away the opportunity from the listener to interpret their ideas based on their own experiences. Only give a small hint through the title.”7

Mägi began piano studies with her sister and advanced to study with a local piano teacher, Karin Prii, in 1938. Prii saw great potential in Ester and suggested that she enroll in the Tallinn Conservatory. Due to World War II and the necessity for many to leave due to governmental restrictions, she studied with four different teachers. Between 1938-1946, Mägi was a student of Helmi Viitol-Mohrfeldi, Artur Lemba, Anna Klas, and Erika Franz.8 In 1946, she suffered an injury to her hand that caused permanent nerve damage and forced her to stop her piano studies. She initially thought that she could no longer continue her music studies, but was then given the option to switch to composition for a temporary placement due to space restrictions in other departments. After one semester, she applied to become a full member of the department by writing two pieces the night before the exam to present for admission.9 Mägi was accepted into the composition studio of Mart Saar and studied with him from 1946-1951. She found that Saar’s personality and style of teaching suited her well and considers him to be her biggest influence. Her slow and methodical approach to composition was matched by his style and she began to create works just from conceptual ideas rather than from past forms and works by other composers. Saar also directed Mägi’s attention to the nationalistic style and to folk music, which were the focus of Soviet governmental dictates on composition during this time. Saar (1882-1963) is known as one of the fathers of Estonian national music.10 His compositions focus on the natural beauty of the area around him and are based on the folklore and songs from that area. He developed the technique of using a folk melody repeatedly in a composition while varying the melodic, harmonic, rhythmic, and textural elements that accompany it. This technique evolved to become known as the national choral symphonic sound in Estonia. Mägi accompanied him on four expeditions to collect folk melodies. She believes that collecting these melodies was the key to understanding the intonation of the nationalistic genre and heritage of the tradition and this was more valuable than duplicating exact melodies and forms. She also studied music literature extensively in order to understand the styles and forms of Western music so that she could appreciate them and apply them to her compositions. Because of her mature and innovative approach as well as the natural logic of her compositions, Mägi was considered by Saar to be much more advanced than her peers. Her innovations with respect to harmony and texture enabled her to become one of the founders of the new Estonian national music style during this time. This style is defined by polyphonic treatment of archaic melodies, but does not require that the original melodies be presented as the primary source.11

Despite her acknowledged debt to Saar, Mägi believes that her true creative path in composition began in 1950, when composers such as Artur Kapp, Cyrillus Kreek and Heino Eller influenced her when she heard their pieces being performed at concerts and song festivals. Kreek is known for his strict presentation of archaic melodies while still being innovative with other aspects of a composition. Eller represents the other end of the spectrum, with fanciful adaptations of folk melodies.12 At this time, these composers were completing their life works while composers such as Eugen Kapp, Gustav Ernesaks and Edgar Arro were emerging and leading a new generation of composers in Estonia.13 Mägi was very inspired by this evolution of style, which combined nationalistic trends with innovative techniques, and gained confidence as a composer through her great success with her Trio for Violin, Cello and Piano in d minor (Klaveritrio d-moll) in 1950. This encouraged her to continue her studies by applying to the Moscow Conservatory. Mägi studied with Vissarion Shelabin and Anatoli Aleksandrov at the Moscow Conservatory from 1951-1954. As she has reflected, it was a very insecure time of her life and she wrote numerous drafts of all of her compositions due to the challenges to her self-image and insecurity that had begun in her youth. The living and studying conditions in Moscow were crowded and noisy, so Mägi rented a work room in a private apartment to study in Moscow and often returned to Tallinn to compose. Moscow was challenging and frustrating, but she did enjoy the rich musical life and attended many concerts at which she was able to meet the performers. Her studies with Shelabin complemented and supplemented her foundational technique and style with a focus more on form. This allowed Mägi to continue the development of her own unique musical language while advancing her knowledge of form and compositional technique. She graduated with the completion of two major scores in 1954: The Concerto for Piano (Klavierikonsert) and the cantata The Journey of Kalevipoeg to Finland (Kalevipoja teekond Soome). The cantata incorporated the influences of the folk melodies, but in a very grand and expansive form. The melodic and harmonic language was advanced, and Mägi also chose to accompany the voices with full orchestra due to the grandiose nature of the subject. Although completed in 1954, The Journey of Kalevipoeg to Finland was not performed until 1961. The reasons for the delay are not known.14

After graduation, Mägi spent time in Virumaal and Saaremaal to explore and collect folk melodies. She continued her study of national intonations, which allowed her to understand the origins of their form more deeply. She returned to Tallinn as a lecturer of analysis and polyphony at the Tallinn State Conservatory until 1984 and continued to compose. Her appointment allowed her to keep updated and aware of compositional trends (while staying true to the foundations created by the past) through her exposure to the numerous professors and lecturers that visited the conservatory. She taught classes at the conservatory during the day and composed in the evenings and on weekends.15 Believing that inspiration for a composition can come at anytime, she carried her compositions with her wherever she went. Moments of inspiration were random and unpredictable: once she sketched new ideas, she took the sketches and wrote the compositions at the piano. Although she felt that there was no need to play everything that she was writing, the process of sitting at the piano helped with her concentration and completion of the musical idea.16 During this process, explorations of textures and instrumentation were married to the more traditional national and folk elements and Mägi’s compositional voice began to emerge ever more clearly and prominently.

Mägi was accepted into the Estonian Composers Union in 1952; at that time, there were only three women members. Although she is interested in the difference between the compositional styles of men and women, she believes that one should judge the value of composers based on their work, not their gender. Naturally self-critical, she does not want to talk about any piece or idea for a composition until it is completed.17 She has earned many awards and titles including: Honorary Art Worker of the Estonian SSR (1971), the Prize of the Soviet Estonia (1980), Popular Artist of the Estonian SSR (1984), the Annual Music Award of the ESSR (1985), the Estonian Culture Award (1996), Fifth Class Order of the National Coat of Arms (1998), honorary doctorate of the Estonian Academy of Music (1999), Lifetime Achievement Award of the Estonian National Culture Foundation (1999) and the Annual Award of the CEE (2001).18

Compositional Styles and Representative Works

Social and Governmental Limitations and Restrictions

At the end of the 1950s in Estonia, the trend in composition was moving away from the national-romantic Russian style, because it was perceived as being too highbrow. Composers were given the assignment by the Estonian government to rebuild the country through music. Governmental expectation stated that compositions should contain music that everyone could understand and relate to as “music for the common people.” Although the Soviet government imposed these restrictions and expectations for Soviet national music, Estonian folk music was considered acceptable because it was perceived as being music for the peasants.19 A true definition of what was national became quite blurred and many compositions were accepted or rejected based on very uneven standards. During this time, communist control over all aspects of intellectual life restricted free composition, but the financial support for scientific research allowed for the exploration of folk music and the continuation of these traditions.20 Composers were required to write works that showed everyday life through art and the music had to be optimistic and uplifting. Settings of sacred texts were prohibited due to the communist system’s belief that religion and the church had a negative influence on society and churches became governmental buildings rather than places of worship.21 Many of the choral pieces composed at this time used folk tales and other secular stories and poetry rather than sacred themes.

Most Estonian composers of this time were educated in Soviet conservatories, where they were encouraged to write in a Russian nationalistic style. All composers were required to belong to the Estonian Soviet Socialist Republic Composers Union (Eesti NSV Helillojate Liit) so that their compositions and other activities could be closely monitored. One of the Estonian composers who was completely silenced by all of the restrictions and chose to leave the country was Arvo Pärt. A devoutly religious person who felt a calling to compose music for the church, Pärt was unable to write freely and chose to emigrate to Germany.22 Although uncomfortable with the restrictions, Mägi was able to balance the restrictions of the government with her personal voice. This allowed her compositions to stay within the boundaries while she preserved her artistic integrity.

Genres

An inquisitive and curious composer, Ester Mägi has composed in every major genre except for stage music. She was asked to compose an opera on the subject of Anton H. Tammsaare’s text, The Burning Farmer (Kõrboja peremees) and accepted the commission. Soon after beginning the composition, she was told that another composer was working on an opera presenting that subject and abandoned the project immediately. Uncomfortable with the restrictions and requirements set by the Soviet regime, Mägi did not accept many requests for commissioned works. The special themes, or specific requirements with respect to ensemble or other aspects of the commission, along with the small amount of time that was given to compose was too much of a challenge for her as a composer. She preferred to have the freedom to compose works inspired from everyday things and favored creative combinations of instruments in her compositions, such as violin, vibraphone and guitar that could not accommodate specific requests. Mägi told me that she was inspired by hearing performers on various instruments at concerts and wanted to write for them to experiment with how specific instruments could be paired together.

Compositional Technique

With a desire to constantly take small bits from all that she was experiencing, Mägi’s music developed with the trends of the time while it continued to respect the strong folk traditions of the past. She tried to keep her compositions fresh and modern by not repeating forms often and internalizing and incorporating new and innovative sounds that she was hearing in other composers’ music. A painfully slow and methodical composer, Mägi stated in an interview with Virve Normet:

I keep the piece with myself and I listen again and again and then there is an explosion of thought and I am embarrassed about what I have written and I have to fix it. There needs to be time between creation and presentation to understand each piece fully.23

She believes that composing music included discussions with performers and the personal experience of rehearsals and she is known in the Estonian musical community for her numerous revisions while she is working on a piece. She believes that a composition has to completely satisfy her before she can share it with the public, so she keeps many pieces for a long period of time and she has retracted some pieces after hearing them in public performances.24 With her preference for strong logical progressions and an established form as a template, Mägi uses a laconic approach to her compositions, with concise statements of the melody and minimal repetition of text.25

At the beginning of her composing career, Mägi’s technique focused on folk melodies that were harmonized in a romantic style. This technique followed the tradition of Mart Saar’s Rahvalaule Soolohäälele (Country/Folk Solo Songs) and is represented through her piece Leidsid sõnad kalli viisi (Leaves Falling), a work whose manuscript has been lost, and also in a women’s choir piece entitled Mõistu (Allegorically). She explored the use of the Setu26 “call and response” style during this time and then returned to it throughout her compositional processes.27 As her compositional explorations progressed, she composed Tormilind (Stormbird) in 1957 for mixed choir. In this work, her harmonic thinking widened to include the use of sevenths and seconds. Plagal cadences create a melancholic mood and an extensive use of text painting portrays the feeling of the storm through the use of a rolling accompaniment in the organ and sharp chordal entrances in the voices. After Tormilind, she continued to write choral compositions, but returned to the traditional and authorized use of folk melodies and text sources. In her work, Hällelaul (Lullaby, 1949), written during this time, there is even mention of strength and unity for the good of communism. This is the only direct mention of the communist ideology in her choral music.

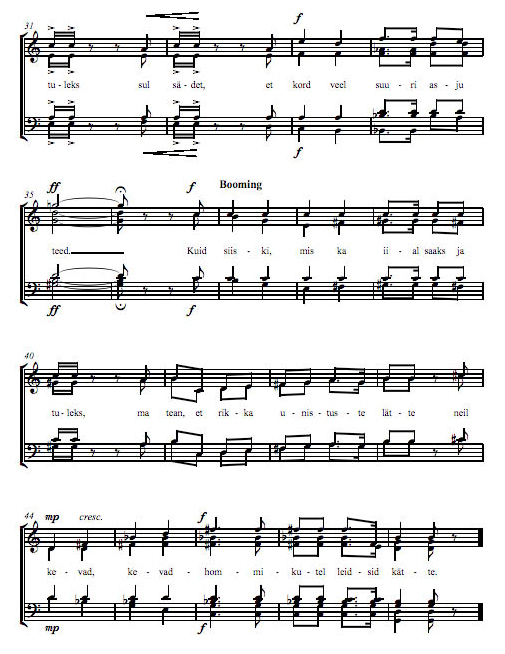

Her first public acclamation came when her composition Õhtul enne naistepäeva (On Women’s Day Eve) won a prize at the national choral competition in 1962. Although still restricted by governmental outlines, the positive public reaction to her work allowed her to feel more freedom with compositional experimentation. Kullerkupud (Globeflower), written in 1965, is based on a folk melody, whereby the melody is varied melodically and then set polyphonically with strict canonic voice pairings. There is a consistent linear movement in paired quartets and a frequent use of quartal harmonies. The use of the Dorian mode and the raised sixth and sub-dominant harmonies became a favorite “watermark” in Mägi’s works. In 1966, with the completion of Hommik (Morning), written for the tenth anniversary for the choir school’s alumni choir concert, Mägi’s compositional style was considered radically new with more complex cadences and chords and a more demanding level expected from the performing ensemble. The advanced techniques in Hommik (Example 1) were incorporated to express heroism rather than tragedy.

Example 1. Hommik, mm. 31-48.

Yet haze halts your ways, and your growth and sparkle can be lost.

As her compositional voice began to flourish, Mägi in the late 1960s and early 1970s began a period of prolific choral writing. She composed for numerous state and city choral ensembles, and many of these pieces received great accolades. Mägi became known as a composer who skillfully married text and music, with innovative and carefully completed melodic ideas. With this surge in popularity, Mägi received a request to compose for the mixed choir of Estonian Television and Radio in 1972.28 A return of focus to the folk roots in 1974 saw her compose only for women’s choir during this time. These compositions are generally diatonic and without modulations.

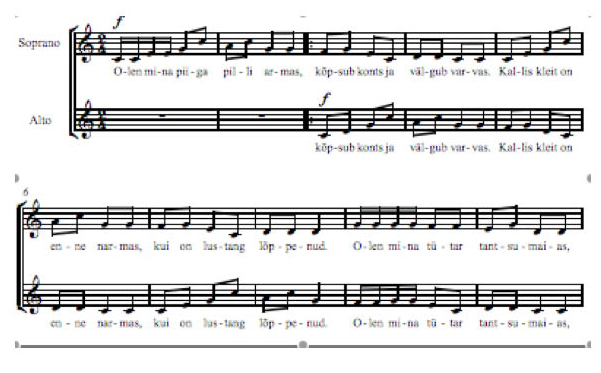

This return to simplicity fostered her use of canons. In her interview with me, she stated that the motivation for using canons was to retain the maximum joy and pleasure of a folk melody for each voice part. The creativity of the canons comes through the the manner in which the singer chooses to sing the line. Singers are allowed to change the rhythmic emphasis and shorten or elongate specific words to create an unique interpretation of the folk tune. (This approach is seen extensively in the compositions of fellow Estonian composer Veljo Tormis.29) Her return to simplicity and folk traditions was received positively, as the Estonian musicologist Karl Leichter states, “These songs have the people’s self-expression that we don’t usually meet in such works.”30 In Example 2 Olen mina piiga armas ( I am a girl who likes to dance, 1985) Mägi begins with a simple triadic canon for two voices and then continues homophonically once the initial statement is completed.

Example 2 “Olen mina piiga armas,” mm. 1-10.

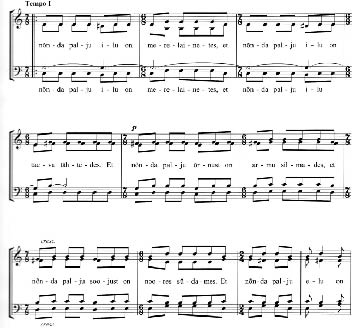

Since that time, Mägi has maintained a balance between respecting the old and exploring the new. (She considers it a great compliment to be told that her compositions sound as if a younger person had written them.)31 This is well represented in her work, Laulikutele (To the Bards, Example 3), in which she seamlessly marries the elements of folk and language with more modern harmonies and textures such as dissonances created by the use of a pedal tone and use of sevenths.

Example 3 Laulikutele, mm. 29-37.

She continued to strive to be creative and advanced in her compositions and to write works that represent the true people and life in Estonia. Due to this yearning for creativity, many of her later compositions (1993-2003) make greater demands on the singers and require a deeper understanding of harmony due to chromatic and dissonant passages. Her last published choral composition Kuugu-Kuugu (Cuckoo-Cuckoo) was completed in 2003, but a manuscript of Ketrajad (Spinning Wheel) was completed in 2005.

Conclusion

As a tribute to her contribution to the canon of Estonian choral music, this essay introduces the reader to the rich societal and artistic history of the Baltic region through the life of Ester Mägi. Magi’s music represents the varied techniques of the composers throughout this time and how these techniques have evolved due to the requirements set by the government. It is my hope that the annotated catalog and unpublished works will be used as a resource for choral conductors to encourage them to explore Estonian choral music without the fear of language and translation. I will continue with this project with the engraving of all of her works to present as a complete collection including a biographical sketch.

Bibliography

Daitz, Mimi. Ancient Song Recovered: The Life and Music of Veljo Tormis. Hillsdale, NY: Pendragon Press, 2004.

Dolan, Marian. Sacred Music of the Baltics: Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania. Minneapolis, MN: Augsburg Fortress, 2003.

Joulud tulevad eesti joululaule. Tallinn: SPMuusikaprojekt, 1998.

Kangron, Tõnu. Eesti NSV 1990. a. üldlaulupeo laule segakoorile. Tallinn: Eesti Raamat, 1988.

Kiaupa, Zigmantas, Ain Mäesalu, Ago Pajur and Gvido Straube. The History of the Baltic Countries. Tallinn: AS BIT, 2002.

Kiilaspea. A. Eesti rahvaviise segakoorile. Tallinn: Eesti Riiklik Kirjastus, 1951.

Kreutzwald, Fr. R. Kalevipoeg. Tallinn: Trükikoda Ühiselu, 1992.

______. Kalevipoeg: An Ancient Estonian Tale. Translated by Jüri Kurman. Moorestown, NJ: Symposia, 1982.

Kuusk, Priit and Mare Põldmäe. Who is Who in Estonia: Music. Tallinn: Tallinna Raamatutrükikoda, 2004.

Kölar, Anu. “Ester Mägi autoriõhtu eel.” Sirp ja vasar (November 21, 1986): 10.

Laar, Mart. Estonia’s Way. Tallinn: Kirjastus Pegasus OÜ, 2006.

Lepnurm, Hugo. “Koos edasitõttava ajaga,” Teater, muusika, kino (1982): 72-78.

Lieven, Anatol. The Baltic Revolution–Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania and the Path to Independence. 2d ed. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1994.

Lippus, Urve. Ester Mägi: Orchestral Music. Program notes. Toccata Classics TOCC 0054, 2007.

______. “Music in Soviet Estonia.” www.okupatsioon.ee/english/overviews/music.html.

Mägi, Ester. Interview with Heather MacLaughlin Garbes. March 15, 2007. Translated by Ulo Krigul. Personal collection of Heather MacLaughlin Garbes, Seattle, WA.

______. Kalevipoja Teekond Soome. Tiraaz: ETÜ, 1960.

______. Koorilaule. Tallinn: Eesti Ramaat, 1982.

______. Koorilaule. Tallinn: SPMuusikaprojekt Muusikakirjastus, 2005.

______. Rivilaul. Tallinn: PI “EKE Projekt”.

______. “Vastab Ester Mägi.” Teater, musiika, kino 1 (1992): 3-8, 94.

Normet, L. and A. Vahter. Soviet Estonian Music: Ten Aspects of Estonian Life. Tallinn: Eesti Raamat, 1967.

Normet, Virve. “ Dialoog Ester Mägi.” Muusika 6 (2003): 2-7.

Olt, Harry. Estonian Music. Tallinn: Perioodika, 1980.

Palmer, Alan. The Baltic: A New History of the Region and its People. Woodstock: NY: Overlook, 2006.

Papp, Evi. “Ester Mägi eesti muusikas.” Teater, muusika, kino. 8 (1984): 31-37.

Puusemp, Ene, Alo Ritsing and Ants Nilson. Gaudeamus 50: Estonian, Latvian and Lithuanian Students’ Song and Dance Festivals, 1956-2006. Tartu, Estonia: Tartu Üliõpilasmaja, 2006.

Ratassepp, A. Estonian Song Festivals. Tallinn: Perioodika, 1985.

Ross, Jaan and Ilse Lehiste. The Temporal Structure of Estonian Runic Songs. New York: Mouton de Gruyter, 2001.

Smidchens, Guntis. “National Heroic Narratives in the Baltics as a Sources for Nonviolent Political Action.” Slavic Review 66, no. 3 (2007).

Soots, Ants. “Ester Mägi-Heli Looja.” Eesti Päevaleht Online (January 8, 2007). www.epl.ee/artikkel/369015.

_______. “Mõtisklused Ester Mägi 85.” Teater, muusika, kino online (March, 2007). www.temuki.ee/index1.htm.

Thomson, Clare. The Singing Revolution: A Political Journey Through the Baltic States. London: Michael Joseph, 1992.

Vahter, A. and L. Normet. Music in the Estonian S.S.R. Tallinn, Eesti Raamat, 1965.

Vettik, T. Twenty Years of Estonian Music. Tallinn: The Estonian Academic Society of Musicians, 1938.

Endnotes

2Normet and Vahter, Soviet Estonian Music, 5.

3Ratassepp, Estonian Song Festivals, 5.

4Lauluväljak is the main arena where the song festivals as well as other concerts are held.

5Clare Thomson, The Singing Revolution, 15-16.

6Interview with Heather MacLaughlin Garbes, March 2007.

7Virve Normet, “Dialoog Ester Mägi,” 5.

10Vahter and Normet, Music, 12.

11Lepnurm, “Koos edasitõttava ajaga,” 112.

13Subin, “Ester Mägi,” 105-108.

14Lepnurm, “Koos edasitõttava ajaga.” 111.

15Normet, “Dialoog Ester Mägi,” 7.

18Kuusk and Põldmäe, Who is Who in Estonia: Music, 79. “CEE” stands for the Central Eastern European Association. That is the complete title of the association.

19Lepnurm, “Koos edasitõttava ajaga,” 106.

20Ross and Lehiste, Temporal Structure, 5.

24Interview with Garbes, March 2007.

25Preface by Järg, in Ester Mägi Koorilaule.

26Setumaa is an area in southeast Estonia in which folk traditions vary greatly from the rest of the traditional runic songs. Setu songs are polyphonic and are generally written for two or three independent parts. Another distinguishing characteristic is the use of a scale constructed on a half-step alternating with steps of three half-steps (D-Eb-F#-G-Bb-B). The metric structure also varies from the runic songs due to the fact that the number of feet stay the same, but combine together to form trochaic feet that incorporate trisyllabic dactylic feet. See Ross and Lehiste, Temporal Structure, 21-22.

27According to Ross and Lehiste (Ibid.) there are two types of Estonian Folk Songs: Baltic-Finnic traditional songs, called “Kalevala,” and runic songs, that is the old folk songs that were composed before the nineteenth centuriy. Both of these styles focus on the natural rhythmic stresses of the text.

28Igav liiv (Eternal Sands) was completed in 1975.