Dear Squeak and Blat:

Hola! I just read Blat’s column in the latest CMS Newsletter about the successful pre-conference on technology at the last national conference in Minneapolis. He spoke about the next one of these coming up at the Richmond, Virginia, meeting next fall on the subject of technology and its assistance with interdisciplinary teaching in music. This sounds kind of interesting to me and wondered if I could get a head start with this idea before the conference. I have been reading a good deal about the CMP days during the late 1960s when schools of music were experimenting with teaching theory, history, and music performance in integrated ways. It would be nice to get back to something like that as we try to breathe new life into college curricula, especially in preparing teachers for today’s public and private schools. How can technology help?

Professor Manuel Integración, Professor of Music History

Comprehensive University

Dear Manuel:

I am excited to see this letter to us. I have been thinking a lot about this lately since my own University is going through an exercise in curriculum reform and strategic planning. I began teaching shortly after the CMP movement and remember studying it and trying to make the ideas happen in my first teaching job. I also am teaching near the state of Wisconsin where many of the public school teachers are experimenting actively with this model and it’s exciting to see this effort taking shape there.

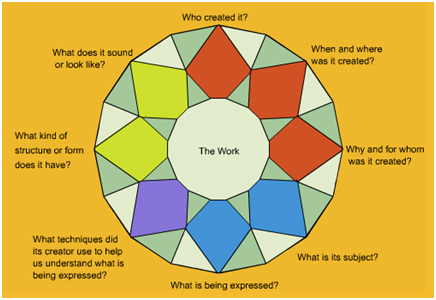

I will put forth a few ideas here that might get you started and my good friend Squeak will take a shot at this, too. A good place to get started is to adopt some kind of structural model for such an effort; I like the Facets Model created by Barrett, McCoy, & Veblen in their excellent book, Sound Ways of Knowing: Music in the Interdisciplinary Curriculum, published by Schirmer, 1997. It looks like this:

At the heart of the model is the piece of music (or any art work) and around the outside are several approaches (or facets) to the study of the work. Each question—such as “who created it” or “what is being expressed” or “what kind of structure or form does it have”—leads to multiple ways to consider the object. One can imagine several additional questions that you might pose for your students to consider as they might be preparing to perform to work. Such a model (and others, too) can form the basis for some interesting curricular efforts that might use technology.

For example, suppose the concert choir at your university is scheduled to perform the Brahms Requiem in the spring. As a music history professor, knowing that your sophomore music history students will be involved, you might consider a class project that uses the Facets Model to study the music from many perspectives. To organize this, you might consider collaborating with both your colleagues in music theory and music education to help with the effort. Imagine an interactive, social networking approach where the key is to encourage blogging or WIKI building. You might consider using Google Sites, a free service that allows the creation of an interactive site to be shared with only specific people, to serve as a place for students and professors to contribute ideas, graphics, sound files, links to places on the web, and video. Instead of a traditional “term paper” that is done by a single person, create small groups of three or four students and charge them with building content on the site that addresses some of the questions in the Facets Model. The work would require documentation, reasoned argument, and the development of a perspective about the work based on scholarship. Results could be shared with all members of the class and other professors could be guest commentators. Groups could be formed with students from the same major, such as music education students or music performance majors in voice; another strategy could be to mix the groups so that students from different majors could bring their perspectives to the group. Besides the gathering of information from the Internet and many other sources, a creative project might be required such as an original podcast, digital movie, a new arrangement of the music, or some other assignment that might use technology tools to demonstrate the group’s understanding of theoretical, historical, or performance practice issues. By doing a project like this, the technology provides the means for students to construct meaning in a comprehensive way and show evidence that they can think across traditional boundaries.

– Blat

Manuel, Blat has provided some wonderful insight into this topic and your question. There are a few points that I might be able to add to this discussion. A recent book greatly informed my thinking on how curriculum and the structure of universities may look in the future. The book is Crisis on Campus: A Bold Plan for Reforming Our Colleges and Universities by Mark C. Taylor at Columbia University. I strongly recommend this to anyone examining curriculum reform in higher education.

Taylor encourages us to move away from a “world of walls and grids” to a networked world: grids are closed, networks are open. As he suggests, “an understanding of how networks operate prepares the way for reconceiving what universities should do and how they should do it.” To create this openness in our curriculum and in the ways we teach depends on tools provided by technology and by those offered through the Internet, especially social networking tools. He provides examples from his own teaching at Williams College and Columbia University that are quite helpful.

Taylor also shares the development of “emerging zones” of study at Columbia as a way to offer new courses of study that bring together expertise from a wide array of disciplines. The “emerging zone” curriculum is seen as extending beyond the traditional three divisions of the natural sciences, social sciences, and arts and humanities. As he explains, Columbia has “begun by developing interdisciplinary programs in five zones of inquiry: Time and Modernities, Space, Transmission, Body, and Media,” all exciting and innovative lines of inquiry that break away from traditional labeling of our specializations and encourage, by their very nature, interdisciplinary sharing of expertise and inquiry.

This concept encourages us as musicians and music educators to consider building bridges for dialogue and discourse across our sub-disciplines in music, but it also encourages us to think much more broadly to bridging to disciplines outside of music. Imagine in this vein a seminar devoted to the influence of music in society (perhaps under the zone of “time and modernities”) where a historian, philosopher, physicist, and sociologist on campus (or invited in via video conferencing) would interact with students in the seminar along with a composer, music educator, ethnomusicologist, and music historian from the music faculty.

I’ve often felt, personally, that the ideal course of study in higher education would be one that permitted a student to choose who to study with at any university in the world with a personal plan of coursework motivated by the student’s sense of inquiry and felt need for research and scholarship. Certainly, there are administrative issues in permitting such academic largesse, but technology and the openness provided by today’s networked world makes such a notion reasonable, not fanciful.

As to how we use technology within our instruction, many of us are focusing on technology-based music instruction. The thinking here draws from the work of Mishra & Koehler (Teachers College Record, June 2006) and their TPCK model (Technological, Pedagogical, Content, and Knowledge ) where technology is an integral component in support of our learning goals and strategies.

As an example, I used the TPCK model in teaching a required graduate research class, integrating technology tools available for research and writing. These tools included online library search engines, bibliographic software aids, enhanced features of word processors, and alternative modes of written expression including blogs and Wikis. The course encouraged open discussion about such topics as plagiarism, copyright, and most importantly, the authentication of authority be it authorship of printed or electronic reference sources.

To return to Taylor’s book, he suggests, “the insistence on narrow research and formats like traditional doctoral dissertations and heavily footnoted scholarly articles unnecessarily limits the creative possibilities for writing and critical thinking.” Our challenge is to find ways to guide our students, retaining the quality of scholarship from the formats of the past, while letting them explore new and innovative forms of expression.

Manuel, I think you will find The College Music Society a wonderfully nurturing organization for these types of discussions. The diversity of our members and their interests, the many opportunities at our events for dialogue, and our close association with ATMI ensures healthy and informative discourse about curriculum revision and innovation that finds creative solutions for using technology in support of music learning.

– Squeak