Playing Beyond the Notes: A Pianist’s Guide to Musical Interpretation, by Deborah Rambo Sinn. New York: Oxford University Press, 2013. ISBN-13: 978-0199859504.

Playing Beyond the Notes: A Pianist’s Guide to Musical Interpretation, by Deborah Rambo Sinn. New York: Oxford University Press, 2013. ISBN-13: 978-0199859504.

Piano teachers often say things like “play with more feeling” or “make that line sound like a clarinet” or “use a joyful forte, not an angry forte.” Students may find these instructions frustrating; it is not at all clear how to evoke joy or a clarinet by pressing down piano keys. Teachers persist in employing vague metaphors because many do not fully understand principles of piano sound. They may know the result they want to hear but cannot give students practical steps toward that goal.

Deborah Rambo Sinn studied with Menachem Pressler and James Tocco, earning her doctorate from Indiana University. She teaches, performs, and presents workshops in the northwestern United States. Her new book Playing Beyond the Notes: A Pianist’s Guide to Musical Interpretation seeks to provide clear principles of piano interpretation for teachers and students, avoiding poetic vagaries in favor of plain and analytical instruction. To assist in this goal, each chapter includes printed musical examples, some of which are also available as audio recordings online.

In the first few chapters she considers the inherent limitations of musical scores, historical performance practice, and the effects of meter. After these cursory introductions, she devotes sustained attention to the precise pacing of ritardandi. She is surprisingly precise, going so far as to illustrate exact moments when a ritardando begins, when it reaches maximum intensity, and when it tapers off. This approach could seem stilted, but as good teachers know, certain students need to be shown how music goes in exhaustive detail. Sinn is capable of explaining a ritardando’s life cycle with exquisite precision.

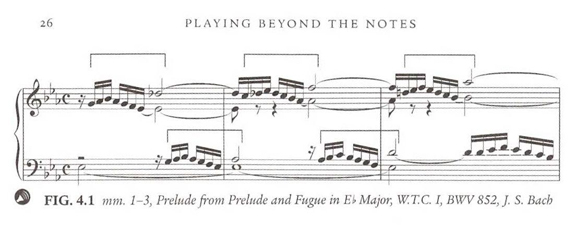

The author also devotes a chapter to the problem of beams and barlines breaking up phrases. She rightly notes that “composers have struggled for years to push past the barline and to communicate these wishes to musicians, but sometimes the music writing conventions of the times thwart their best efforts” (p. 25). She gives many examples of how musical ideas almost always cross the beams and barlines to arrive at the next strong beat. In the following example the author shows with brackets the manner in which each sub-phrase crosses over beams or barlines:

The chapter on voicing recommends dividing the piano sound into melody, bass, and inner voices (in that order of priority). At this point the reader begins to sense the limitations of a book that is about sound. Pianists who already understand voicing will immediately understand and agree with the author; students who do not create good tone production are likely to miss the point. Piano voicing needs to be taught and demonstrated with a vividness that is probably not possible within the pages of a book.

The chapter on ornamentation encounters the same problem: it is difficult to explain sound in words. Sinn describes a particular ornament as clearly as possible but in mild desperation concludes that “care should be taken to handle the grace note with, well, grace” (p. 59). As in the case of voicing, most of the instruction on ornamentation will make sense to someone who already knows how good ornaments are played. The website offers a few audio examples of both voicing and ornamentation, and while these may be helpful to students, perhaps they are best seen as a starting point rather than as comprehensive instruction.

Sinn devotes a chapter to phrase structure in which she illustrates how larger phrases are built up from shorter ones: ultimately, the strong-weak relationship of the two-note phrase. The theoretical foundations of her teaching are admirable and perhaps too rare among pianists. Likewise, the chapter on pedaling is free of sentimental nonsense. She sweeps aside several generations of tradition (“A pianist should disregard almost all pedaling indications in scores”) and enumerates clear and practical principles of using the damper pedal on the piano.

The numerous musical examples throughout the book are helpful, and recordings on the publisher’s website demonstrate many of the author’s points. The audio examples are generally good, except that they are recorded at too low a level. Nuances of phrasing and tone can be lost even at maximum volume. This oversight could be easily corrected with audio software. Occasionally the examples do not quite illustrate the author’s point; in a few cases the printed musical example shows, for instance, a certain dynamic or phrasing plan that the recording does not quite carry out. In one example (from Beethoven’s Piano Sonata in A Major, Op. 101) the dotted rhythms are unfortunately played as triplets. Nonetheless, the vast majority of recordings are musically excellent; Sinn is a good pianist and capable of “walking her talk.” Indeed, one might wish for longer recorded examples or complete pieces.

The book would have benefited from closer editing for occasional awkward phrasing (“metronome markings are the single-most least-reliable element of any score”), graphic layout (a misplaced musical example in one instance), and for the very rare actual music theory mistake (claiming that the Neapolitan chord is “exceptionally unusual” in Schumann’s music).

The musical examples are all taken from the standard repertoire, and lean toward frequently performed Classical and Romantic literature. The difficulty level is aimed at pre-college or early college students. This choice represents an understandable compromise: readers who need this book are more likely to follow if the examples are drawn from familiar repertoire (though others may lament that the book appears to reinforce the calcification of the classical repertoire).

Sinn’s book could be helpful in giving teachers and students a working vocabulary of musical terms. Simply having terminology for various musical events will cause teachers and students to become aware of those events and address them more intelligently. Checklists provide a summary of each chapter’s ideas; these could serve as useful guides for group discussions among students. Ideally, the concepts in the book should be reinforced with live teaching and demonstration.

The author makes no claim of comprehensive instruction in interpretation, intending instead that multiple examples in the text will spark the student’s own analytical fire. This is a good approach, since the author herself regularly encounters the problem of articulating broadly-applicable principles of musical interpretation: “When the bass line comprises a steady stream of sixteenth notes, there are several options to consider. Should a performer bring out all of the notes, just the first note of each set, or something in between? In different passages, any of these could be a good answer.” Likewise: “In pieces such as these, the best plan is to experiment and find a balance of notes that fits well with one’s overall interpretation of the piece.”

Playing Beyond the Notes is a useful and intelligently written book and seems to represent years of accumulated teaching wisdom. Sinn is tireless in the pursuit of solving passages unto the last sixteenth note, and often refreshingly precise in her explanations. If the book is any indication, she is likely a fine teacher. Despite some inevitable limitations of writing about sound, the book will allow teachers and students to think analytically about common interpretive situations at the piano.