Abstract

Mozart Violin Concerto in D Major, K. 271a/271i, also known as Kolb Concerto, is less popular than other Mozart concertos due to its unsettled authenticity, and yet is a piece worth learning. In this concerto Mozart, if he wrote it, seemed to have not only maintained his previous violin concerto writing style but also started exploring new ways of writing. Aimed at college music students, violin teachers, and professional performers, this article calls attention to this rarely performed violin concerto. The author synthesizes background information, such as authenticity and viewpoints of many musicologists, about this concerto from various sources and provides practical information, such as publications and performances, for those who are interested in knowing and learning the concerto.

James A. Grymes

Leopold Mozart published his famous Treatise on the Fundamental Principles of Violin Playing in 1756, the year of Wolfgang’s birth. Being one of the most distinguished violin pedagogues of his time, Leopold naturally expected his son to be a violinist. In fact, young Wolfgang began to learn the violin at about age six, and even wrote two pieces for the instrument during that time, his Violin Sonata no. 1 in C Major (K. 6) and Violin Sonata no. 2 in D Major (K. 7), both in 1762–1764. Among many anecdotes, the following story depicts the young Mozart’s incredible talent in playing the violin. Reportedly, this happened before his formal violin training began in 1762.

Before he had received any regular lessons, his father was one day visited by a violinist named Wenzl [Hebelt], an excellent performer, for the purpose of trying over some new trios of his composition. [Johann Andreas] Schachtner the trumpeter, who tenderly loved the little musician, has related the anecdote connected with this performance. “The father,” he says, “took the bass part on the viola, Wenzl played the first violin, I the second. Little Wolfgang entreated that he might play the second violin; his father, however, would not hear of it, for as he had had no instruction, it was impossible that he could do anything to the purpose. The child replied, that to play a second violin part it was not necessary to have been taught; but the father, somewhat impatiently, bid him go away and not disturb us. At this he began to cry bitterly, and carried his little fiddle away, but I begged that he might come back and play with me. The father at last consented. ‘Well, then, you may play with Herr Schachtner, but remember, so softly that nobody can hear you, or I must immediately send you away.’ We played, and the little Mozart with me, but I soon remarked to my astonishment that I was completely superfluous. I silently laid my violin aside and looked at the father, who could not suppress his tears. Wolfgang played the whole of the six trios through with precision and neatness; and our applause at the end so emboldened him that he fancied he could play the first violin. For amusement we encouraged him to try, and laughed heartily at his manner of getting over the difficulties of this part, with incorrect and ludicrous fingering indeed, but still in such a manner that he never stuck fast” (Holmes and Hogwood 1991, 8–9).

The boy learned the violin so fast, in “lightning progress” (Banat 1986b, 9), that he was appointed Konzertmeister of the Salzburg court orchestra on November 27, 1770, when he was fourteen. Mozart’s new job might have inspired him to write violin music, since he was expected to perform solo works as the orchestra leader.

Mozart’s first major composition for the violin was his Violin Concerto no. 1 in B-flat Major (K. 207, 1773).1The original date of K. 207 is unclear from the manuscript. Some put 1775 as the composition year, while Wolfgang Plath, the Mozart handwriting specialist, suggested 1773 as the year of composition. See Gabriel Banat, “Introduction to the Autographs” in The Mozart Violin Concerti: A Facsimile Edition of the Autographs (New York: Raven, 1986), 20. At this point, Mozart’s mastery over the violin had already reached the level that he was able to sightread any violin concertos (Anderson 1966, 236). K. 207 was followed by the Concertone for Two Violins and Orchestra in C Major (K. 190/186e, 1774).2In most cases, when two Köchel numbers are given, the first number is from the first edition (1862) and the second is from the sixth edition (1964) of the Köchel Catalog. However, the subject of this article is an exception. It was not included in the first edition because Ludwig von Köchel did not know of its existence. Only in the second edition (edited by Paul von Waldersee in 1905) did the concerto make an appearance in the Köchel Catalog. See Dennis Pajot, “K271a Violin Concerto in D,” in Mozart Forum (2007), https://web.archive.org/web/20070926231550/http://www.mozartforum.com/Lore/article.php?id=096 Mozart’s crowning moment in violin concerto writing came in 1775, when he composed four violin concertos within six months. “The five violin concertos of that year [K. 207 was probably written two years earlier] tell us a great deal about Mozart’s artistic development,” Friedrich Blume (1956, 222) observed, adding, “and in the course of writing them he made extraordinarily rapid progress in composition, such as any other composer would have required decades to achieve.” All five violin concertos, together with K. 271a/271i of 1777, “demonstrate Mozart’s lively interest in the instrument at this time” (Abert 2007, 342).

Although it is regrettable, especially for violin players, that Mozart wrote no more violin concertos during his late years,3In his letter from Paris to his father (11 September 1778), Mozart declared “I shall not be kept to the violin, as I used to be. I will no longer be a fiddler.” He stopped playing the violin completely at the age of twenty-four. When he played chamber music, he would play the viola (Banat 1986, 7). seven are preserved (see Appendix A). No.1 in B-flat Major (K. 207) was written in 1773, and the next four (K. 211, K. 216, K. 218, and K. 219) were composed almost uninterruptedly between June and December in 1775. These five are known as Mozart’s genuine works, while the authenticity of the last two, K. 271a/271i (K. 271i hereafter), known as the Kolb Concerto,4It is uncertain who the “Kolb” was, since Leopold Mozart did not use the given name in his related letter of 3 August 1778 to his son. Carl Bär believed it was likely to be either Joachim or Johann Andreas Kolb, sons of Franz Xavier Kolb. See Dennis Pajot (2007). Christoph-Hellmut Mahling listed Franz Xaver Kolb in Series X (p. xx) of the Neue Mozart-Ausgabe in 1980, but Johann Anton Kolb in Series V (p. ix) in 1983; and back to Franz Xaver Kolb in the “Preface” of the Bärenreiter’s music score in 2006. See “Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Concertos,” in Neue Mozart-Ausgabe, https://dme.mozarteum.at/DME/nma/nmapub_srch.php?I=2. See also W. A. Mozart Concerto in D Major for Violin and Orchestra KV2 271a (271i): Piano Reduction Based on the Urtext of the New Mozart Edition by Martin Schelhass (New York: Bärenreiter, 2006), v. The changes seem to reflect ongoing research. and K. 268/Anh. C14.04 (K. 268 hereafter), is questioned to different degrees. This paper concentrates on K. 271i.</p

History and Background

The original manuscript of K. 271i is not extant. Maynard Solomon (1995, 310) mentioned that Mozart’s widow Constanze destroyed some sketches and drafts after Mozart’s death. Erich Hertzmann (1957, 191) also pointed out that in Constanze’s letter of 21 July 1800 to music publisher Johann Anton André, she stated that she destroyed “the unusable autographs” of Mozart. It is possible that the original K. 271i, if it ever existed, was among the destroyed manuscripts.

There are only two copies available, known as the Berlin copy and the Paris copy, neither of which are in Mozart’s hand. The Berlin copy, once in the collection of Aloys Fuchs (1799–1853), is in the Berlin State Library (the former Prussian State Library). While the source of the original manuscript from which the Berlin copy was made is unknown, it was from that copy that Breitkopf & Härtel published the work in 1907, making it available to the public for the first time.

The Paris copy is a reproduction of an autograph manuscript that is said to have been in the possession of François Antoine Habeneck (1781–1849), a French conductor, composer, and violinist. The violinist Charles Eugène Sauzay (1809–1901) made a copy from this autograph manuscript for his teacher and later father-in-law Pierre Marie François de Sales Baillot (1771–1842), the legendary violinist and influential pedagogue of the French School of violin playing. The copy contained the statement and date which Sauzay reproduced as follows: Concerto per il Violino di Wolfgango Amadeo Mozart Salisburgo Ii 16 di Luglio 1777 [Concerto for the Violin by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Salzburg, 16 July 1777]. The Paris copy, in the private collection of Charles Eugène Sauzay’s son Julien in Paris (Abert 2007, 363, f. 104), is shorter than the Berlin copy, perhaps to suit the Parisian taste.5The Parisian taste was known as fancy but concise. In a letter of 11 September 1778 to his father during his Paris visit, Mozart noted that his Salzburg symphonies were “not in the Parisian taste.” He continued, “If I have time, I shall rearrange some of my violin concertos, and shorten them. In Germany we rather like length, but after all it is better to be short and good.” See Emily Anderson, The Letters of Mozart and His Family (London: Macmillan, 1966), 615. We do not know which violin concertos were in Mozart’s mind, but the Paris copy of K. 271i is indeed shorter than the Berlin copy. Thus, Mahling considered the Berlin copy to be the “original version.” See Christoph-Hellmut Mahling, “Preface,” in W. A. Mozart Concerto in D Major for Violin and Orchestra KV2 271a (271i): Piano Reduction Based on the Urtext of the New Mozart Edition by Martin Schelhass (New York: Bärenreiter, 2006), v–vi.

The numbering of the concerto has been problematic. Abert (1923/1924/2007, 342) designated K. 271i as “a sixth.” It was also labelled as Concerto No. 6 in D Major, K. 271a in Angel’s 1963 recording (conducted and performed by Yehudi Menuhin with Bath Festival Orchestra). However, Alberto Bachmann listed K. 271i as No. 7 in his 1925 book An Encyclopedia of the Violin (Da Capo, 1986, reprint). In the Longmans Miniature Arrow Score Series (Longmans, 1940), K. 271i was similarly placed as the seventh of Mozart’s violin concertos, after K. 268. We also find the work titled Concerto No. 7 in D Major for Violin and Orchestra (K. 271a) in EPIC’s 1955 recording (performed by Arthur Gruminaux with Vienna Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Bernhard Paumgartner). The inconsistency also affects the numbering of K. 268. Carl Fischer (1916) catalogued K. 268 as No. 6, but G. Schirmer (1921) and Peters (1922) listed it as No. 7. In the 1987 Sheet Music Catalog of Shar Music, both K. 268 and K. 271a were under the title of Concerto No. 7. Overall, K. 271i is designated more often as No. 7, perhaps based on its publication date. K. 268 was first published (by Johann A. André) in 1799, while K. 271i did not appear in print until the Breitkopf & Härtel edition in 1907. The decision on the numbering might be also derived from the editor’s viewpoint. For example, if the editor considers the date of compositions, then using “No. 6” for K. 271i (1777) and “No. 7” for K. 268 (1780) seems logical. Furthermore, if the editor accepts K. 271i as Mozart’s but rejects the authenticity of K. 268, then K. 271i would be “No. 6” and there would be no “No. 7.”

Breitkopf & Härtel’s publication of K. 271i initiated a lasting debate on its authorship. Alfred Heuss (1907–1908, 125) described “the overwhelming wealth of thematic elements” of the concerto as being “genuinely Mozartian.” Abert (1923/1924/2007, 363) believed the work to be authentic because “the concerto’s traditional form is still clearly recognizable in both the overall design and the structure of the individual movements, with the usual four tuttis and three solos effortlessly identifiable in the opening movement.” He also mentioned “typically Mozartian abruptness” in the second subject of the first and third movements, concluding, “There are no grounds for doubting its authenticity: it reveals so many Mozartian features that any other composer is simply out of the question.” In responding to concerns that the presence of double-stopping in tenths and passages in the high register were atypical for Mozart, Blume (1956, 217) asked “why theses peculiarities of violin technique should be the basis for throwing doubt on the authenticity of the entire concerto.”

Other scholars, however, were not convinced that the work was Mozart’s, largely arguing that it is difficult to determine how much of the concerto is by Mozart, and how much of it might have altered by the copyist or copyists. Alfred Einstein (1945, 281) thought that K. 271i “is certainly not preserved in the form in which Mozart wrote it—if, in fact, he ever wrote it out as more than a hasty sketch.” In his biography of Mozart, Stanley Sadie (1970, 136) wrote, “No sensitive music-lover can accept K. 268 or K. 271a as pure Mozart, though there may be traces of his work in them somewhere.” Ten years, later, in The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (Sadie 1980, v. 12, 693), Sadie suggested that K. 271i and K. 268 “may include music of Mozart’s in adulterated form: their sources are dubious and their style uncharacteristic.” H. C. Robbins Landon (1988, 572) echoed the earlier concern about stylistic consistency: “what has puzzled everyone is the solo violin writing, with its high positions, double-stopping in tenths, etc., which never appear in the authentic Mozart violin concertos.”

This hesitation is expected given the unsettled authenticity issue.6For further information on the controversy, see Alfred Heuss, “Mozart’s Seventh Violin Concerto,” Monthly Journal 9 no. 1 (1907): 124–29. See also Carl Bär, “Betrachtungen zum umstrittenen Violinkonzart 271a,” in Mitteilungen der Internationalen Stiftung Mozarteum 11, no. 3/4 (1963): 11ff; Dimitri Petrovic Kolbin, “Zur Frage der Echtheit des Violinkonzerts D-Dur von W. A. Mozart (KV 271a–i),” in Musykalnoye ispolnitelstvo (Moscow, USSR, 1972): VII, 266–303; W. A. Mozarts Violinkonzerte (Konservatorija Lvov, USSR, 1973) and Christoph-Hellmut Mahling, “Bemerkungen zum Violinkonzert D-dur, KV 271i,” in Mozart und seine Unwelt (Bubingen, Germany: BRD, 1978/79): 252–68. Landon (1990) did not comment on the concerto in The Mozart Compendium. Instead, he merely listed the concerto as being “doubtful” (353). It is interesting to notice that in the first edition of New Grove (1980), Sadie listed the concerto under “Doubtful and spurious violin concertos,” together with K. 268 (v. 12, 741). In the second edition (2001), however, “Doubtful” was separated from “Spurious” (v. 17, 328), making a distinction between the two categories. Because of the regrouping, the authorship of K. 271i remained “Doubtful,” while K. 268 was moved to “Spurious,” reflecting ongoing research into these two works. The Köchel Catalogue added the concerto to the second edition (1905) as K. 271a, and changed it to K. 271i in the sixth edition (1964, edited by Franz Giegling, Gerd Sievers, and Alexander Weinmann), while moving K. 268 to Anh[ang] [Appendix] C: Doubtful and misattributed vocal and instrumental works. The Neue Mozart-Ausgabe [New Mozart Edition] excluded K. 268 but included K. 271i in the supplemental series as one of the doubtful works, implying that K. 271i was potentially genuine, or at least, the current status in research cannot designate it as an absolute forgery, like K. 268.7It is generally agreed that K. 268 was composed by Johann Friedrich Eck (1767–1838), the Munich violinist. See “Editorial Principles,” in Neue Mozart-Ausgabe, Series X: Supplement, Work Group 29: Works of Dubious Authenticity (1980): v.1, viii. At present, Christoph-Hellmut Mahling’s hypothesis of five possibilities still stands (Dennis Pajot 2007):

1. The concerto is by Mozart;

2. The concerto is Mozart’s arrangement of a violin concerto by someone else;

3. The concerto as we know it is someone else’s arrangement of a Mozart violin concerto;

4. The concerto is by someone else, but has been mistakenly attributed to Mozart;

5. The concerto is a forgery.

The “someone else” could be Baillot or Rodolphe Kreutzer (1766–1831) given the French elements in the concerto. Besides conviction and rejection about the authenticity of the work, Mahling (1980, xx) reported “an intermediate view, that Mozart had indeed created the ‘framework’ and the ‘core’ of the work, but that it had received its final appearance from a foreign hand.” He continued, “Since this version gained increasing favour in the course of time, the problem became less that of Mozart’s authorship at all but rather that of the extent of his contribution to this work.”

Editions

Unlike Mozart’s authentic violin concertos, there are not many editions of K. 271i. The first complete edition of K. 271i (1907, edited by Albert Kopfermann for the Neue Mozart-Ausgabe) was prepared from the Berlin copy. The score is now freely available online, thanks to the International Music Score Library Project. Among the later editions, Bärenreiter’s piano reduction (2006, edited by Martin Schelhaas) is of interest. Based on the scores of both the Berlin and the Paris copies, with more weight on the former, this edition includes three violin parts:

- Urtext [original version] from the Neue Mozart-Ausgabe.

- A performance version with fingerings, bowings, and comments on performance by Martin Wulfhorst.

- Cadenzas and Eingänge from both the Berlin and the Paris copies, and Martin Wulfhorst’s own cadenzas and Eingänge.

Equally valuable is the Preface by Christoph-Hellmut Mahling, who introduces the background of the concerto in detail. The Russian piano reduction (edited by I. M. Yampolskov, State Musical Publishing House, Moscow, 1949) includes dynamic markings, fingerings, and bowings, along with cadenzas by George Enescu. This edition may serve as a practical performing version. Other publications include, but are not limited to, Hans Sitt and Otto Taubmann’s edition by Breitkopf & Härtel, and Rolland Jones’s Cadenzas for the Violin Concerti Nos. 1–7 by Jones Publishing.

Possible Genesis

The five authentic concertos were likely intended for Mozart’s own use in his capacity of Konzertmeister. He probably played all or some of them. For example, in his letter of 23 October 1777 Mozart reported to his father, “in the evening, at supper-time, I played the Strassburg Violin Concerto.8Scholars have disagreed on which work was the Strassburg Concerto. Some have thought it was Concerto No. 4 in D Major, K. 218 (Louis Biancolli, The Mozart Handbook, 436; H. C. Robbins Landon and Donald Mitchell, eds, The Mozart Compendium, 215; and Stanley Sadie, Mozart, 136); while others believed it was Concerto No. 3 in G Major, K. 216 (A. Hyatt King, Mozart Wind & String Concertos, 17; Maynard Solomon, Mozart, 102; Anderson, The Letters of Mozart and His Family, 297; and The New Grove [1980], 693). It was difficult to find the answer because Mozart did not reveal any identifiable information about the concerto in his letter. The debate eventually ended in 1956, when Dénes Bartha identified that it was Concerto No. 3 in G Major, K. 216, based on a theme “Strassburger” in the third movement of K. 216. The discovery was described in detail by Gabriel Banat in his “Mozart and the Violin,” in The Mozart Violin Concerti, 14–15. Köchel lists Concerto No. 3 in G Major, K. 216 Strassburg. It went like oil. All praised the lovely pure tone” (Mersmann 1972, 39). On the other hand, Mozart might have written them and K. 271i for Antonio Brunetti (1744–1786)9Mozart often mentioned Brunetti in his letters, but did not use the given name. Some scholars believed it was Gaetano Brunetti (Biancolli, The Mozart Handbook, 609; Alfred Einstein, Mozart, “Index of Names,” 486; Max Kenyon, Mozart in Salzburg, 130; Landon and Mitchell, The Mozart Companion, 389; and Hans Mersmann, Letters of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, 273); while others thought it was Antonio Brunetti (Anderson, The Letters of Mozart and His Family, 275 f.2; Otto Erich Deutsch, Mozart: Die Dokumente seines Lebens, 1961; Cliff Eisen and Simon P. Keefe, The Cambridge Mozart Encyclopedia, 108; Mahling, The Neue Mozart-Ausgabe, ix; and Solomon, Mozart, 241, 309). It became clear when the second edition of New Grove (2001) added new entries for the Brunetti family members. It should be Antonio Brunetti. (Blume 1956, 223), who was his deputy and soloist in the Salzburg court orchestra and succeeded Mozart as Konzertmeister in 1777 when he was released from employment. It was certainly for Brunetti that Mozart composed three independent concerto movements and a sonata around that time—Adagio in F Major, K. 261 (1776), Rondo in B-flat Major, K. 269 (1775–1777), Rondo in C Major, K. 373 (1781), and Violin Sonata No. 27 in G Major, K. 379/373a (1781).

The inspiration for K. 271i is not as clear. There is no dedication indicated for the concerto, but there are some traces of historical background that we may consider as possible motivation for the composition. In Mozart’s time it was not uncommon for works to be published in sets of six. For example, in February 1766 Mozart wrote six violin sonatas (K. 26 through K. 31) and dedicated them to Princess Caroline (Banat 1986b, 10). In early 1775 he composed six piano sonatas (K. 279 through K. 284, numbers from Köchel 1) in Munich. Johann Christian Bach (1735–1782), Mozart’s contemporary, also wrote many sets of six compositions: Op. 5 (1765), Op. 11 (1772), Op. 16 (1780), Op. 17 (1780), and so on. It is therefore possible that Mozart also planned a set of six violin concertos.

Another possibility can be traced back to a historical event. During the 1770s the Mozart family had the custom of celebrating on 26 July the joint “name day” of Anna Maria, the matriarch of the family, and her daughter Maria Anna (“Nannerl”). The celebration would typically feature an evening concert, for which Mozart would compose a new work. Both Carl Bär and Dimitri Petrovic Kolbin believed that Mozart wrote the concerto for Franz Xaver Kolb to play on Nannerl’s name day on 26 July 1777 (Mahling 1980, xx). Joachim Ferdinand von Schiedenhofen (1747–1823), a friend of Mozart’s, mentioned in his diary of 25 July 1777 that the July 1777 “name day” concert would include a violin concerto which Mozart might play by himself (Deutsch 1966, 161). This could be Concerto in D Major, K. 271i, as A. Hyatt King suggested (1978, 31).

It is also possible that Mozart wrote the concerto “on the basis of his need for a display piece during his Paris visit” in 1778 (Biancolli 1954, 432), as the flashy style of the concerto suited the Parisian taste for virtuosity. When discussing the musical style in Paris during 1770s, Georges Saint-Foix (1968, 65) offered, “public demand was for ‘solo’ instruments in the symphonies, and the growing taste for virtuosity especially favored all soloists.” He suggested that the French Violin School might have played a role “in Mozart’s conception of the violin concerto” (56). Similarly, Abert (2007, 364) noticed that in this concerto, “French ideas that were aimed in essence at virtuosic brilliance are now suddenly raised to a new and higher level.” He continued, “Mozart wrote this piece with the Paris public in mind: brilliance and charm are its basic characteristics, and superficial effects, especially of a purely technical order, play a far greater role than in the earlier concertos.”

The Concerto

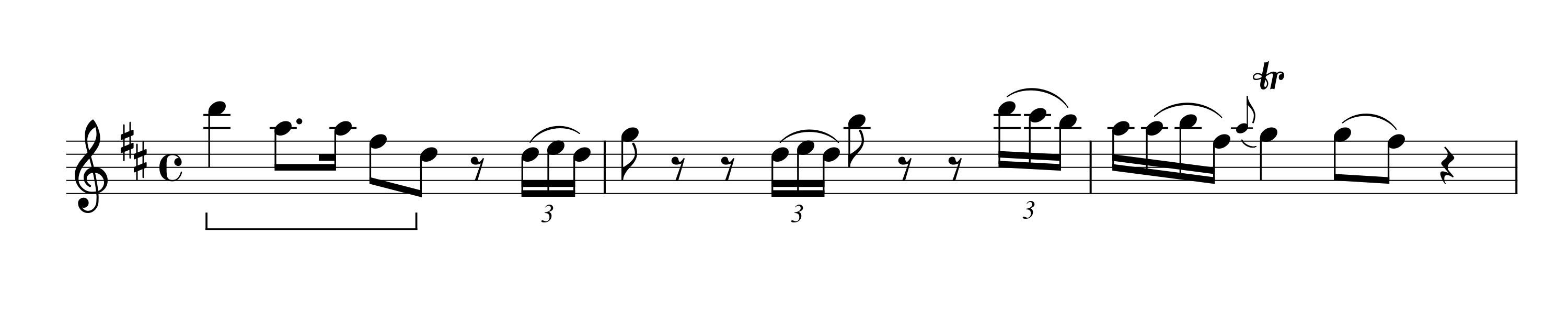

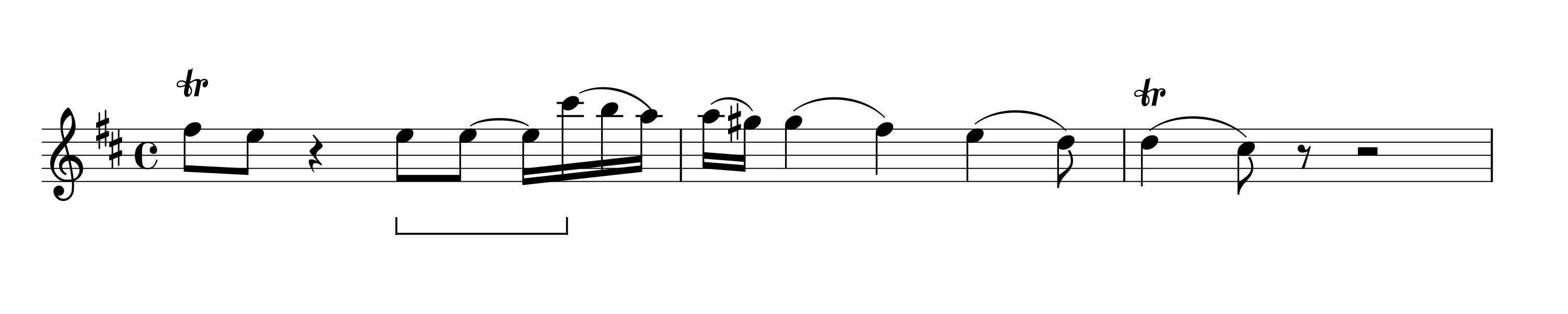

Mozart’s violin concertos present a distinguished style. Overall, they are characterized by their elegance, simplicity, virtuosity, expressive melodies, and clear form and structure. The themes are equally distributed between the solo violin and the orchestra. One recognizable feature of the Mozartian style is the use of the broken triad as a thematic motif. This particular pattern shows the connection between K. 271i and the authentic ones. (See examples 1a, 1b, 1c, 1d, 1e).

Broken triad as motif

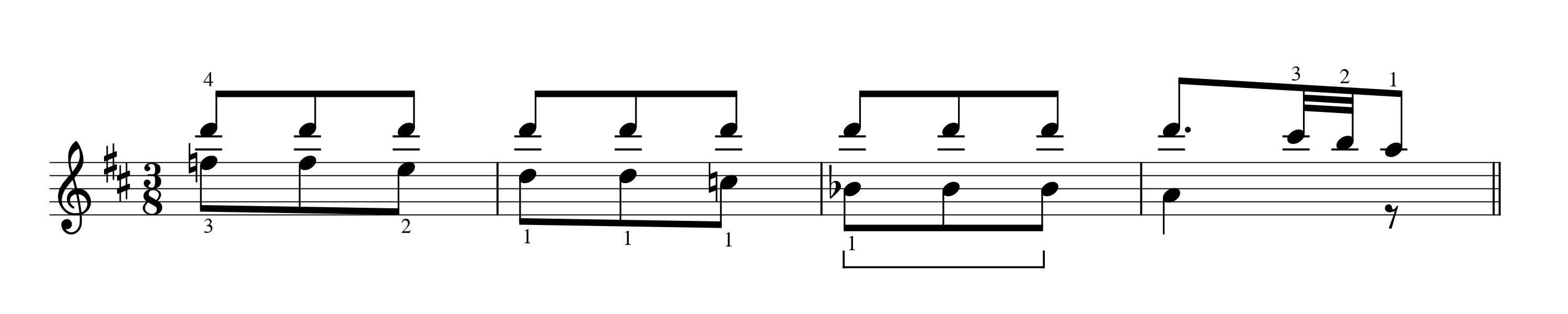

Example 1a. K. 271i, first movement, bars 27-32

Example 1b. K. 211, first movement, bar 22-24

Example 1c. K. 216, first movement, bars 51-54

Example 1d. K. 218, first movement, bars 42-45

Example 1e. K. 219, first movement, bars 40-41, 46-47

Mozart’s writing of violin concerto reached a noticeable maturity stage at No. 3 in G Major, K. 216. From then on, we see a sequence of tonality coinciding with the circle of fifths: No. 3 in G Major, K. 216, No. 4 in D Major, K. 218, and No. 5 in A Major, K. 219. One might expect that the next concerto could be in E Major. Instead, K. 271i is the third in D Major among the total of six concertos. D Major is a friendly key for the violin player because of the easy string resonance and comfortable fingering patterns. One can find a good number of famous violin concertos written in this key: Beethoven, Brahms, Paganini, Tchaikovsky, just to name a few.

Apart from the unusual technique challenges, K. 271i displays a youthful spirit often found in Mozart’s music. The French influence seen in this concerto is more of a technical matter (high positions and double-stopping) rather than musical. The orchestration is typical of Mozart. Like all five authentic concertos, K. 271i is scored two oboes, two horns, and strings. It is more idiomatic of Mozart’s arrangement than that of K. 268, the forgery, which also includes one flute and two bassoons.

The overall structure of the concerto is also Mozartian. The concerto is arranged in the order of Sonata–Allegro and Rondo–Allegro with an expressive slow movement in the middle. The plan is consistent with Mozart’s previous four (Nos. 2–5) concertos. (No. 1 has Presto instead of Rondeau for the third movement.) The similarities to violin concertos that have been definitively attributed to Mozart are clearest in the first movement of K. 271i, which resembles K. 211 not only in key but also in style. For example, both initiate the first theme with a broken (arpeggiated) tonic triad in the same direction, descending. (See examples 1a and 1b).

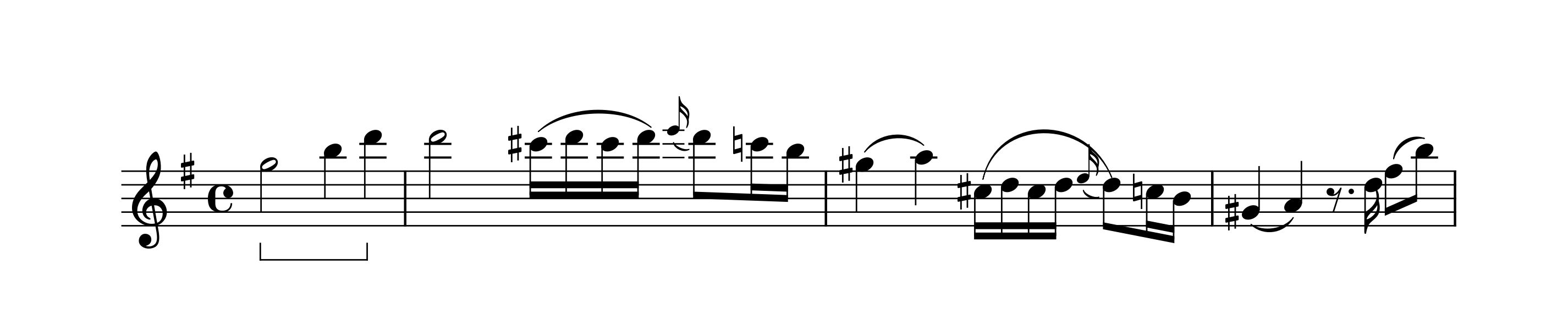

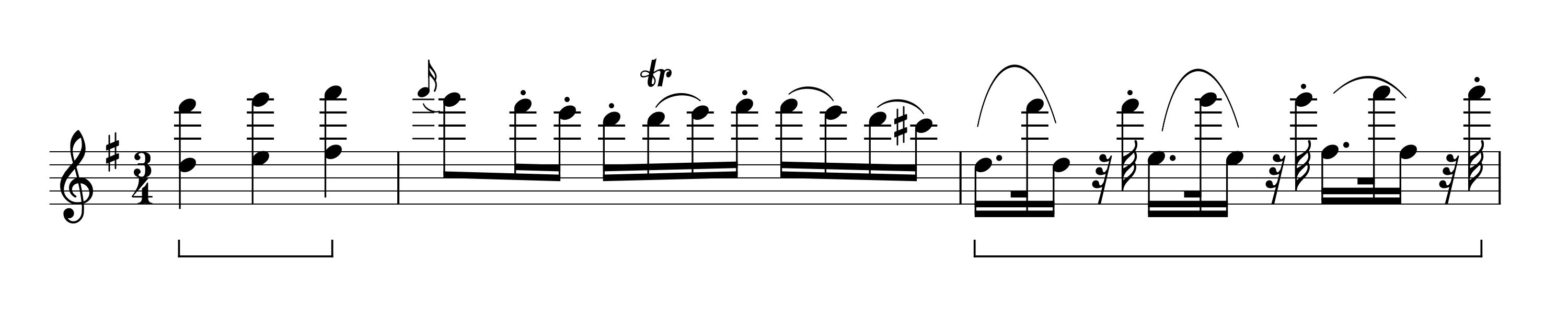

The resemblance occurs again when the second theme in both is introduced in dominant with an ascending major sixth. (See examples 2a and 2b). We also see a frequent use of triplets throughout the first movement of both K. 211 and K. 271i.

Second theme comparison

Example 2a. K, 271i, first movement, bars 49-51

Example 2b. K. 211, first movement, bars, 30-32

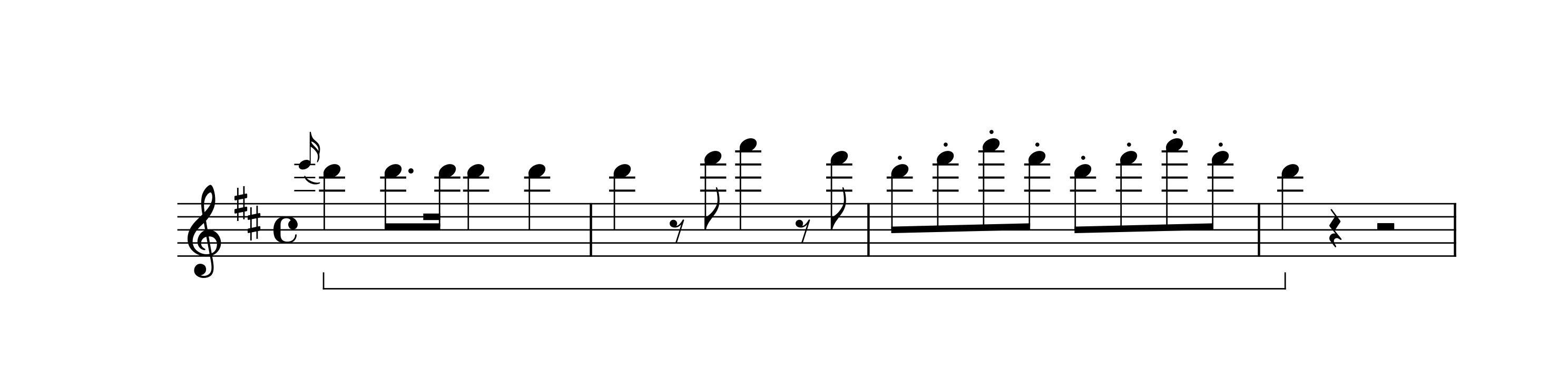

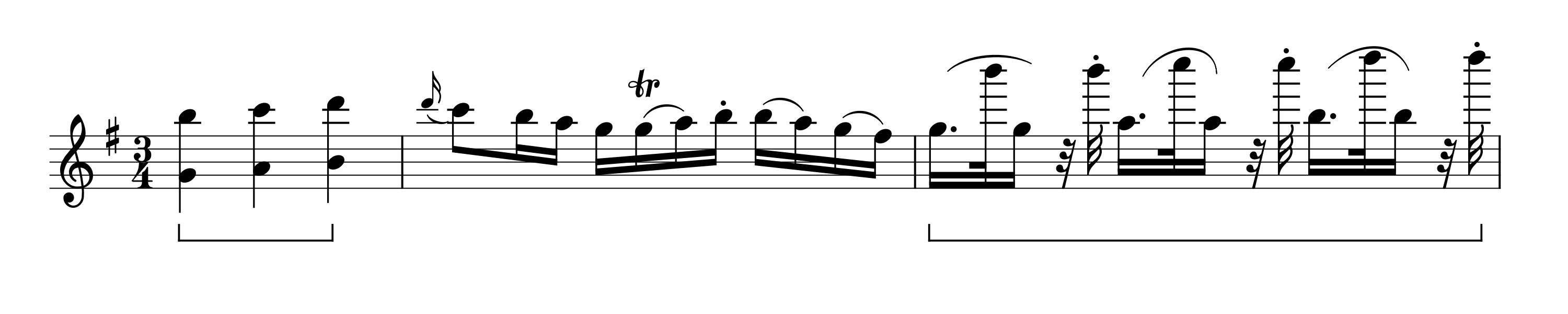

The second movement is the least conventional in several ways. The five-bar main theme of the lyrical Andante is presented four times by the string section pizzicato. The solo violin echoes the strings with its own pizzicato in the recapitulation. The use of pizzicato is quite extraordinary. As a comparison, Antonio Vivaldi (1678–1741) used pizzicato for Violin II in his Concerto for Three Violins in F Major, RV 551, for the entire second movement, but it is more of an accompaniment rather than a leading theme. Perhaps the most unusual writing is double-stopping, specifically in tenths, which Mozart had never used in his previous violin concertos. (See examples 3a and 3b).

Double-stopping in tenths

Example 3a. K. 271i, second movement, bars 39-41

Example 3b. K.271i, second movement, bars 97-99

Although evidenced in Leopold Mozart’s 1756 method book that playing tenths was in practice in Mozart’s time (see examples 4a and 4b), writing double-stopping in tenths was not particularly popular until Paganini’s time.

Exercises of tenths in double-stopping by Leopold Mozart

Example 4a. A Treatise on the Fundamental Principles of Violin Playing, page 157

Example 4b. A Treatise on the Fundamental Principles of Violin Playing, page 157

In general, people with large hands have an advantage in playing tenths. Michael Kelly, an Irish operatic singer in Vienna in Mozart’s time, described Mozart as “a remarkably small man”10Edward Holmes and Christopher Hogwood. The Life of Mozart, Including His Correspondence (London: Folio, 1991), 201. Hogwood added, “Mozart’s height is said to have been 1.5 metres [4ft 11in].” f.*. Hogwood did not point out the original source. who had “small hands.”11Holmes and Hogwood, 281. This supports the theory that Mozart might have written the concerto for someone else, such as Kolb or Brunetti.

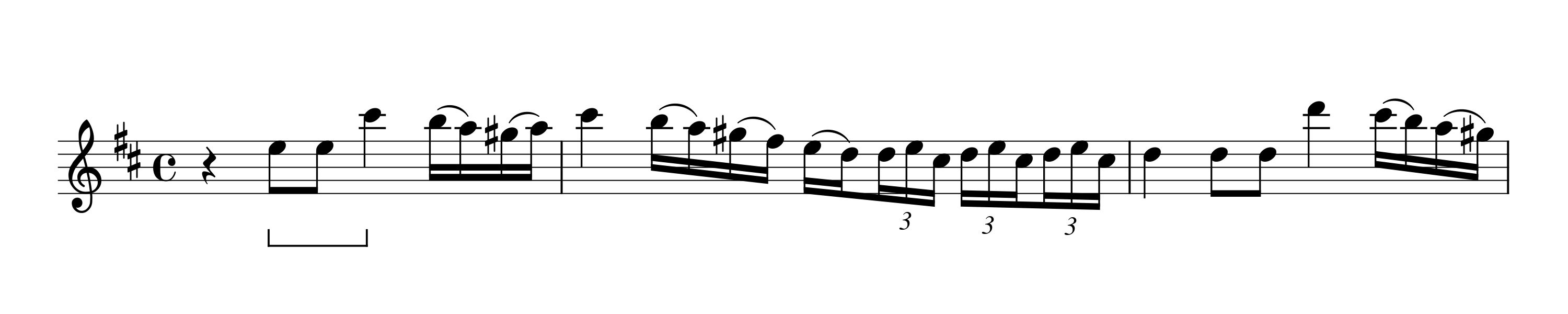

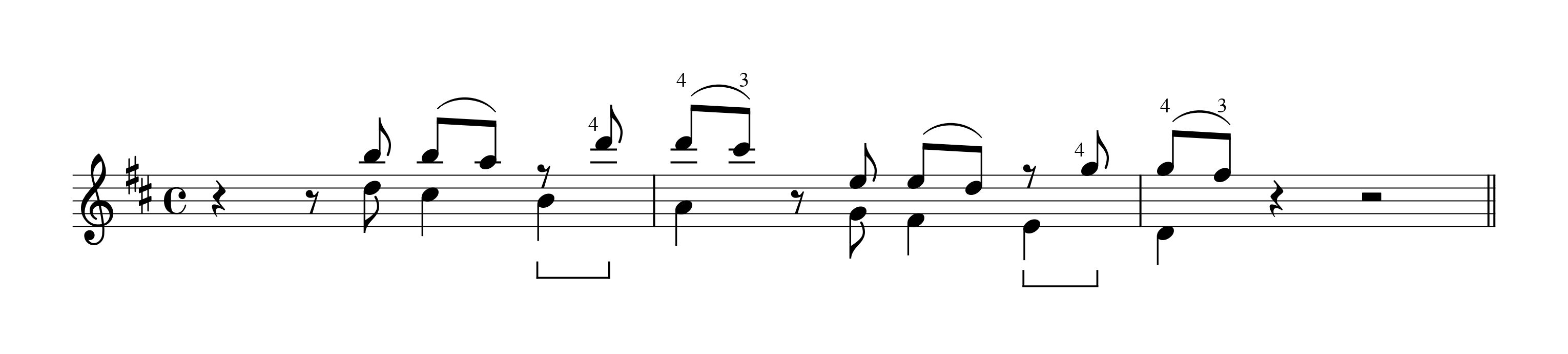

It is noticeable, as some musicologists (Heuss 1907–1908, 125; Biancolli 1954, 432; Landon and Mitchell 1969, 217) have pointed out, that the final Rondo contains a motif also used by Mozart in his ballet Les petits riens, K. 299b/Anh.10 (Paris 1778), namely No. 6 Gavotte Joyeuse. If the main themes of the first movement are similar to K. 211, this one is almost identical. (See examples 5a and 5b).

Theme comparison

Example 5a. K. 271i, third movement, bars 171-179

Example 5b. K. 299b/Anh. 10, no. 6 Gavotte Joyeuse, bars 8-16

It seems that in writing his ballet Mozart might have borrowed the thematic materials from K. 271i, which had been written a year earlier. This is strong evidence to support the view that K. 271i is authentically Mozart.

Comparing with the other rondos in Mozart’s authentic violin concertos, one remarkable thing of K. 271i’s third movement is its incredible length: 539 bars in total (502 in the Paris copy), where K. 211 has 179 bars; K. 216, 433; K. 218, 243; and K. 219, 249. Perhaps this movement was the target that Mozart wanted to trim for his Parisian audience.

Conclusion

In this concerto, we find traces of both conventional and unconventional writing styles. The music shows certain touches of alterations which are said to have been made by Sauzay and Baillot, or Kreutzer (Pajot 2007). Some scholars and violinists have rejected the work as being Mozart’s based on the high demand on technique, such as high positions and double-stopping in tenths which were not, after all, typical in Mozart’s time. However, if Mozart did indeed compose the concerto, the change of style might have come from the result of his stylistic development in general, and his “love of experimentation found particularly fertile ground in his violin concertos” (Abert 2007, 363) in particular.

When introducing K. 271i and K. 268, Louis Biancolli (1954, 432) wrote, “From a musical and technical standpoint they are markedly different from the five violin concertos of 1775 [the first one, K. 207, was actually written in 1773], although they fall comfortably enough within the general framework of what one may call a Mozartean [sic] style.” As Tovey (quoted in Hutchings, 1976, Part 2, 42) remarked, if K. 271i was indeed a forgery, “then it was a very clever one” that did not “make the mistake of imitating a generalized Mozart of no particular period.” Even though he firmly doubted the concerto’s authenticity, Landon (1988, 572) admitted, “It is a very cleverly constructed work.” He continued, “and if—as the reader will have gathered—I very much doubt whether Mozart can have been the composer, that is no reason not to play it. There are a great many concertos that are frequently performed but are not nearly so interesting as this sprightly (as I suppose) 19th century pastiche.”

This author advocates for inclusion of this concerto in our repertoire for several reasons. Firstly, the concerto has not been proven as completely inauthentic. The current status in the most authoritative reference sources, The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, The Neue Mozart-Ausgabe, and Köchel Catalog, indicates that the concerto is merely a doubtful work, not a known forgery as in the case of Concerto in E-flat Major, K. 268.

Secondly, even if the concerto might be written by someone else, it nevertheless remains an excellent example of the High Classic Style of Mozart and others. “Very close analysis reveals that K. 271a (271i) is characteristic of Mozart’s technique; and not one passage allows of any room for doubt in regard to themes, harmony, rhythm, construction, and orchestration; the structure is, in fact, directly connected with that of K. 218 and K. 219” (Blume 1956, 217). The phenomenon of “in the style of” compositions, such as Fritz Kreisler (1875–1962)’s Praeludium and Allegro in the Style of [Gaetano] Pugnani [(1731–1798)] and Henri Casadesus (1879–1947)’s Viola Concerto in the Style of J[ohann] C[hristian] Bach [(1735–1782)], among others, does not seem to diminish our pleasure of performing such works.

Lastly, the fact that some leading violinists of the twentieth century performed and recorded K. 271i shows the musical and historical value of the concerto. The first documented public performances of the concerto after Breitkopf & Härtel’s publication were held in Dresden by Henry Petri and in Leipzig by Catharina Bosch, respectively, both on November 4, 1907.12“Reviews,” Monthly Journal (The International Music Society, Leipzig, Breitkopf & Härtel) 9, no. 1 (1907): 135. It was one of the works performed by the sixteen-year-old Yehudi Menuhin under George Enescu during a visit to England in 1932. The concerto was one of Menuhin’s favorite works, as evidenced by the multiple recordings he made of it. Salvatore Accardo, under Ettore Gracis, made a fine recording at the Conservatorio di San Pietro a Majella in Italy in 1962. Josef Suk, under Libor Hlaváček, recorded all seven Mozart concertos including K. 268 and K. 271i in 1972–1973. (For more recordings see Appendices B and C). It is time for the new generations to carry on the venture, perform, and make recordings of it.

Although the authenticity issue may never be settled, we may as well enjoy this wonderful piece. The author studied this concerto as a student at conservatory with my professor. We used a Russian edition (Yampolskov, ed.). I found it fresh, compared to Mozart’s earlier violin concertos, and fun to play. There may be passages that are not by Mozart, but, to quote King (1978, 31), “such anomalies and defects are not enough to detract from enjoyment of the concerto as a whole.”

Notes

[1] The original date of K. 207 is unclear from the manuscript. Some put 1775 as the composition year, while Wolfgang Plath, the Mozart handwriting specialist, suggested 1773 as the year of composition. See Gabriel Banat, “Introduction to the Autographs” in The Mozart Violin Concerti: A Facsimile Edition of the Autographs (New York: Raven, 1986), 20.

[2] In most cases, when two Köchel numbers are given, the first number is from the first edition (1862) and the second is from the sixth edition (1964) of the Köchel Catalog. However, the subject of this article is an exception. It was not included in the first edition because Ludwig von Köchel did not know of its existence. Only in the second edition (edited by Paul von Waldersee in 1905) did the concerto make an appearance in the Köchel Catalog. See Dennis Pajot, “K271a Violin Concerto in D,” in Mozart Forum (2007), https://web.archive.org/web/20070926231550/http://www.mozartforum.com/Lore/article.php?id=096

[3] In his letter from Paris to his father (11 September 1778), Mozart declared “I shall not be kept to the violin, as I used to be. I will no longer be a fiddler.” He stopped playing the violin completely at the age of twenty-four. When he played chamber music, he would play the viola (Banat 1986, 7).

[4] It is uncertain who the “Kolb” was, since Leopold Mozart did not use the given name in his related letter of 3 August 1778 to his son. Carl Bär believed it was likely to be either Joachim or Johann Andreas Kolb, sons of Franz Xavier Kolb. See Dennis Pajot (2007). Christoph-Hellmut Mahling listed Franz Xaver Kolb in Series X (p. xx) of the Neue Mozart-Ausgabe in 1980, but Johann Anton Kolb in Series V (p. ix) in 1983; and back to Franz Xaver Kolb in the “Preface” of the Bärenreiter’s music score in 2006. See “Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Concertos,” in Neue Mozart-Ausgabe, https://dme.mozarteum.at/DME/nma/nmapub_srch.php?I=2. See also W. A. Mozart Concerto in D Major for Violin and Orchestra KV2 271a (271i): Piano Reduction Based on the Urtext of the New Mozart Edition by Martin Schelhass (New York: Bärenreiter, 2006), v. The changes seem to reflect ongoing research.

[5] The Parisian taste was known as fancy but concise. In a letter of 11 September 1778 to his father during his Paris visit, Mozart noted that his Salzburg symphonies were “not in the Parisian taste.” He continued, “If I have time, I shall rearrange some of my violin concertos, and shorten them. In Germany we rather like length, but after all it is better to be short and good.” See Emily Anderson, The Letters of Mozart and His Family (London: Macmillan, 1966), 615. We do not know which violin concertos were in Mozart’s mind, but the Paris copy of K. 271i is indeed shorter than the Berlin copy. Thus, Mahling considered the Berlin copy to be the “original version.” See Christoph-Hellmut Mahling, “Preface,” in W. A. Mozart Concerto in D Major for Violin and Orchestra KV2 271a (271i): Piano Reduction Based on the Urtext of the New Mozart Edition by Martin Schelhass (New York: Bärenreiter, 2006), v–vi.

[6] For further information on the controversy, see Alfred Heuss, “Mozart’s Seventh Violin Concerto,” Monthly Journal 9 no. 1 (1907): 124–29. See also Carl Bär, “Betrachtungen zum umstrittenen Violinkonzart 271a,” in Mitteilungen der Internationalen Stiftung Mozarteum 11, no. 3/4 (1963): 11ff; Dimitri Petrovic Kolbin, “Zur Frage der Echtheit des Violinkonzerts D-Dur von W. A. Mozart (KV 271a–i),” in Musykalnoye ispolnitelstvo (Moscow, USSR, 1972): VII, 266–303; W. A. Mozarts Violinkonzerte (Konservatorija Lvov, USSR, 1973) and Christoph-Hellmut Mahling, “Bemerkungen zum Violinkonzert D-dur, KV 271i,” in Mozart und seine Unwelt (Bubingen, Germany: BRD, 1978/79): 252–68.

[7] It is generally agreed that K. 268 was composed by Johann Friedrich Eck (1767–1838), the Munich violinist. See “Editorial Principles,” in Neue Mozart-Ausgabe, Series X: Supplement, Work Group 29: Works of Dubious Authenticity (1980): v.1, viii.

[8] Scholars have disagreed on which work was the Strassburg Concerto. Some have thought it was Concerto No. 4 in D Major, K. 218 (Louis Biancolli, The Mozart Handbook, 436; H. C. Robbins Landon and Donald Mitchell, eds, The Mozart Compendium, 215; and Stanley Sadie, Mozart, 136); while others believed it was Concerto No. 3 in G Major, K. 216 (A. Hyatt King, Mozart Wind & String Concertos, 17; Maynard Solomon, Mozart, 102; Anderson, The Letters of Mozart and His Family, 297; and The New Grove [1980], 693). It was difficult to find the answer because Mozart did not reveal any identifiable information about the concerto in his letter. The debate eventually ended in 1956, when Dénes Bartha identified that it was Concerto No. 3 in G Major, K. 216, based on a theme “Strassburger” in the third movement of K. 216. The discovery was described in detail by Gabriel Banat in his “Mozart and the Violin,” in The Mozart Violin Concerti, 14–15. Köchel lists Concerto No. 3 in G Major, K. 216 Strassburg.

[9] Mozart often mentioned Brunetti in his letters, but did not use the given name. Some scholars believed it was Gaetano Brunetti (Biancolli, The Mozart Handbook, 609; Alfred Einstein, Mozart, “Index of Names,” 486; Max Kenyon, Mozart in Salzburg, 130; Landon and Mitchell, The Mozart Companion, 389; and Hans Mersmann, Letters of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, 273); while others thought it was Antonio Brunetti (Anderson, The Letters of Mozart and His Family, 275 f.2; Otto Erich Deutsch, Mozart: Die Dokumente seines Lebens, 1961; Cliff Eisen and Simon P. Keefe, The Cambridge Mozart Encyclopedia, 108; Mahling, The Neue Mozart-Ausgabe, ix; and Solomon, Mozart, 241, 309). It became clear when the second edition of New Grove (2001) added new entries for the Brunetti family members. It should be Antonio Brunetti.

[10] Edward Holmes and Christopher Hogwood. The Life of Mozart, Including His Correspondence (London: Folio, 1991), 201. Hogwood added, “Mozart’s height is said to have been 1.5 metres [4ft 11in].” f.*. Hogwood did not point out the original source.

[11] Holmes and Hogwood, 281.

[12] “Reviews,” Monthly Journal (The International Music Society, Leipzig, Breitkopf & Härtel) 9, no. 1 (1907): 135.

References

Abert, Hermann. 2007. W.A. Mozart. Edited by Cliff Eisen. Translated by Stewart Spencer. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Originally published in German by Breitkopf & Härtel, 1923–1924.]

Anderson, Emily. 1966. The Letters of Mozart and His Family. London: Macmillan.

Banat, Gabriel. 1986a. “Introduction to the Autographs.” In The Mozart Violin Concerti: A Facsimile Edition of the Autographs, 19–28. New York: Raven.

Banat, Gabriel. 1986b. “Mozart and the Violin.” In The Mozart Violin Concerti: A Facsimile Edition of the Autographs, 7–18. New York: Raven.

Bär, Carl. 1963. “Betrachtungen zum umstrittenen Violinkonzart 271a.” [Reflections on the Controversial Violin Concerto 271a.] In Mitteilungen der Internationalen Stiftung Mozarteum [Communications of the International Mozarteum Foundation] 11, no. 3/4:11 ff.

Biancolli, Louis. 1954. The Mozart Handbook: A Guide to the Man and His Music. New York: The World.

Blume, Friedrich. 1956. “The Concertos.” In The Mozart Companion. Edited by H. C. Robbins Landon and Donald Mitchell. New York: Oxford University Press, 200–33.

Deutsch, Otto Erich. 1966. Mozart: A Documentary Biography. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Einstein, Alfred. 1945. Mozart: His Character, His Work. Translated by Arthur Mendel and Nathan Broder. New York: Oxford University Press.

Eisen, Cliff, and Simon P. Keefe. 2006. The Cambridge Mozart Encyclopedia. Edited by Cliff Eisen and Simon P. Keefe. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Hertzmann, Erich. 1957. “Mozart's Creative Process.” The Musical Quarterly 43, no. 2: 187–200.

Heuss, Alfred. 1907–1908. “Mozart's Seventh Violin Concerto.” Monthly Journal (The International Music Society, Leipzig, Breitkopf & Härtel) 9, no. 1: 124–29.

Holmes, Edward, and Christopher Hogwood. 1991. The Life of Mozart, Including His Correspondence. London: Folio.

Hutchings, Arthur. 1976. Mozart: The Man, The Musician. New York: Schirmer.

Kenyon, Max. 1979. Mozart in Salzburg: A Study and Guide. Westport: Hyperion.

King, A. Hyatt. 1978. Mozart Wind and String Concertos. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Kolbin, Dimitri Petrovic. 1973. W. A. Mozarts Violinkonzerte. [W. A. Mozart’s Violin Concertos]. USSR: Konservatorija Lvov.

Kolbin, Dimitri Petrovic. 1972. “Zur Frage der Echtheit des Violinkonzerts D-Dur von W. A. Mozart (KV 271a–i).” [The Authenticity of Mozart’s Violin Concerto in D Major, K. 271a–i]. In Musykalnoye ispolnitelstvo [Musical performance]. VII, 266–303. Moscow, USSR.

Landon, H. C. Robbins. 1988. “Controversial Köchels: On the Authenticity of Mozart’s 6th and 7th Violin Concertos.” Strad 99, no. 1179, 571–72.

Landon, H. C. Robbins. 1990. The Mozart Compendium: A Guide to Mozart's Life and Music. London: Thames and Hudson.

Landon H. C. Robbins, and Donald Mitchell, eds. 1956. The Mozart Companion. New York: Oxford University Press.

Mahling, Christoph-Hellmut. 1978/79. “Bemerkungen zum Violinkonzert D-dur, KV 271i.” [Remarks to the Violin Concerto in D Major, KV 271i]. In Mozart und seine Unwelt. [Mozart and His Environment], 252–68. Bubingen: BRD.

Mahling, Christoph-Hellmut. 1980. “Foreword.” In The Neue Mozart-Ausgabe, X/29/1, ix–xxiii. International Mozart Foundation, Online Publications. https://dme.mozarteum.at/DME/nma/nmapub_srch.php?l=2

Mahling, Christoph-Hellmut. 1983. “Foreword.” In The Neue Mozart-Ausgabe, V/14/1, viii–xiii. International Mozart Foundation, Online Publications. https://dme.mozarteum.at/DME/nma/nmapub_srch.php?l=2

Mahling, Christoph-Hellmut. 2006. “Preface.” In W. A. Mozart Concerto in D Major for Violin and Orchestra KV2 271a (271i): Piano Reduction Based on the Urtext of the New Mozart Edition by Martin Schelhass, v–vi. New York: Bärenreiter Kassel.

Mersmann, Hans. 1972. Letters of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. Translated by M. M. Bozman. New York: Dover.

Mozart, Leopold. 1756. A Treatise on the Fundamental Principles of Violin Playing. Translated by Editha Knocker. Second edition (1951). New York: Oxford University Press.

Pajot, Dennis. 2007. “K271a Violin Concerto in D.” In Mozart Forum. https://web.archive.org/web/20070926231550/http://www.mozartforum.com/Lore/article.php?id=096

Sadie, Stanley. 1970. Mozart. New York: Grossman.

Sadie, Stanley. 1980. “Mozart, Wolfgang Amadeus.” In The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. Edited by Stanley Sadie, volume 12, 680–752. London: Macmillan.

Saint-Foix, Georges. 1968. The Symphonies of Mozart. New York: Dover.

Solomon, Maynard. 1995. Mozart: A Life. New York: HarperCollins.

APPENDIX A

Mozart Violin Concertos

Violin Concerto No. 1 in B-flat Major, K. 207

Movements: Allegro moderato, Adagio, Presto

Composed: Salzburg, Spring 1773

Violin Concerto No. 2 in D Major, K. 211

Movements: Allegro moderato, Andante, Rondeau allegro

Composed: Salzburg, June 1775

Violin Concerto No. 3 in G Major, K. 216, “Strassburg”

Movements: Allegro, Adagio, Rondeau allegro

Composed: Salzburg, September 1775

Violin Concerto No. 4 in D Major, K. 218

Movements: Allegro, Andante Cantabile, Rondeau Andante grazioso – Allegro ma non troppo

Composed: Salzburg, October 1775

Violin Concerto No. 5 in A Major, K. 219, “Turkish”

Movements: Allegro aperto – Adagio – Allegro aperto, Adagio, Rondeau Tempo di menuetto – Allegro

Composed: Salzburg, December 1775

Violin Concerto in E-flat Major, Anh. C14.04

Movements: Allegro moderato, Un poco Adagio, Rondo Allegretto

Composed: Munich? 1780 or before 1790

Note: K. 268 in Köchel 1st edition; 365b in Köchel 3rd edition. Work of forgery, hence, reassigned in Köchel 6th edition as anhang [appendix] C14.04.

Violin Concerto in D Major, K. 271a/i, “Kolb”

Movements: Allegro maestoso, Andante, Rondo Allegro

Composed: Salzburg or Paris? Summer 1777

Note: 271a in Köchel 2nd edition, changed to 271i in Köchel 6th edition.

APPENDIX B

Recordings of Mozart Violin Concerto in D Major, K. 271a/i

(Arranged by date)

Yehudi Menuhin (violin), Violin Concerto in D Major, by W. A. Mozart with Orchestre Symphonique De Paris, conducted by George Enescu, recorded 1932, Warner Classics.

David Oistrakh (violin), Violin Concerto in D Major, by W. A. Mozart with USSR State Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Kirill Kondrashin, recorded 1950, The Orchard Music.

Arthur Grumiaux (violin), Violin Concerto in D Major, by W. A. Mozart with Wiener Symphoniker, conducted by Bernahrd Paumgartner, recorded 1955, Heritage.

Yehudi Menuhin (violin), Violin Concerto in D Major, by W. A. Mozart with London Mozart Players, conducted by Harry Blech, recorded 1956, Ica Classics.

Yehudi Menuhin (violin), Violin Concerto in D Major, by W. A. Mozart with Bath Festival Orchestra, conducted by Yehudi Menuhin, recorded 1963, Angel Records.

Henryk Szeryng (violin), Violin Concerto in D Major, by W. A. Mozart with New Philharmonia Orchestra, conducted by Sir Alexander Gibson, recorded 1966, Philips.

Josef Suk (violin), Violin Concerto in D Major, by W. A. Mozart with Prague Chamber Orchestra, conducted by Libor Hlaváček, recorded 1972–1973, SME (on behalf of Eurodisc).

Cho-Liang Lin (violin), Violin Concerto in D Major, by W. A. Mozart with English Chamber Orchestra, conducted by Raymond Leppard, recorded 1990, Sony.

Mela Tenenbaum (violin), Violin Concerto in D Major, by W. A. Mozart with Czech Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by Richard Kapp, recorded 1991, Supraphon.

David Garrett (violin), Violin Concerto in D Major, by W. A. Mozart with Chamber Orchestra of Europe, conducted by Claudio Abbado, recorded 1995, Deutsche Grammophon.

Christiane Edinger (violin), Violin Concerto in D Major, by W. A. Mozart with Europa Symphony, conducted by Wolfgang Gröhs, recorded 1997, Arte Nova.

Hiro Kurosaki (violin), Violin Concerto in D Major, by W. A. Mozart with Cappella Coloniensis, conducted by Hans-Martin Linde, recorded 2010, Capriccio.

Mirijam Contzen (violin), Violin Concerto in D Major, by W. A. Mozart with Bavarian Chamber Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by Reinhard Goebel, recorded 2011, Oehms.

Mayumi Fujikawa (violin), Violin Concerto in D Major, by W. A. Mozart with Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by Walter Weller, recorded 2015, Australian Eloquence.

Liya Petrova (violin), Violin Concerto in D Major, by W. A. Mozart with Sinfonia Varsovia, conducted by Jean- Jacques Kantorow, recorded 2021, Mirare.

APPENDIX C

Recordings of Mozart Violin Concerto in D major, K. 271a/i on YouTube

(Arranged by YouTube publishing date)

Diodato ‘Uto’ Ughi (violin), Violin Concerto in D Major, by W. A. Mozart with Orchestra dell'Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia, conducted by Diodato ‘Uto’ Ughi, YouTube (22 May 2013), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q-CBGP_H7K8.

Note: Live video recording

Mela Tenenbaum (violin), Violin Concerto in D Major, by W. A. Mozart with Czech Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by Richard Kapp, YouTube (3 August 2013), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4OWyj6JeaK8.

Note: ESSAY Recordings

Thomas Zehetmair (violin), Violin Concerto in D Major, by W. A. Mozart with Philharmonia Orchestra, conducted by Thomas Zehetmair, YouTube (24 September 2014), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-s8KghLOd14.

Note: ℗ 1992 Teldec Classics, a Warner Music UK Division

Arthur Grumiaux (violin), Violin Concerto in D Major, by W. A. Mozart with Vienna Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Bernhard Paumgartner, YouTube (11 November 2014), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-mWt67Rp6D0.

Note: Recording released on 15 June 2014. Saland Publishing

Henryk Szeryng (violin), Violin Concerto in D Major, by W. A. Mozart with London Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Karl Böhm, YouTube (18 January 2015), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uoaJvj9HPGg.

Note: Live recording, 5 August 1973, Salzburg, Austria

Michail Fikhtenkholz (violin), Violin Concerto in D Major, by W. A. Mozart with Moscow Philharmonic Chamber Orchestra, conducted by David Oistrakh, YouTube (19 March 2015),

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4zra9IlBg38.

Christiane Edinger (violin), Violin Concerto in D Major, by W. A. Mozart with Europa Symphony, conducted by Wolfgang Gröhs, YouTube (29 April 2015), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b7qonSjD540.

George Enescu (violin), Violin Concerto in D Major, 2nd movement, by W. A. Mozart with The Magic Key Orchestra (NBC Symphony Orchestra), conducted by Franck Jeremiah Black, YouTube (13 February 2016), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-sGfk1f35-0.

Note: NBC Radio Broadcast, live, March 14, 1937

Aïda Stucki (violin), Violin Concerto in D Major, by W. A. Mozart with Orchestre de Chambre de Lausanne, conducted by Victor Desarzens, YouTube (28 January 2017),

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GMaa1d1UO_I.

Salvatore Accardo (violin), Violin Concerto in D Major, by W. A. Mozart with ‘Alessandro Scarlatti’ Orchestra of Naples by RAI, conducted by Ettore Gracis, YouTube (21 February 2017), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KH8dLLJIqiU.

Note: Recording made at the Great Hall of the ‘San Pietro a Majella’ Conservatory on 6 March 1962

Alina Pogostkina (violin), Violin Concerto in D Major, by W. A. Mozart with WDR Sinfonieorchester Köln, conducted by Reinhard Goebel, YouTube (4 April 2017), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vTZQqHkD47g.

Note: Live Recording, 27 June 2014, Funkhaus Wallrafplatz, Cologne, Germany

David Oistrakh (violin), Violin Concerto in D Major, by W. A. Mozart with USSR State Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Kirill Kondrashin, YouTube (3 December 2017), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZIdC7zakxWk.

Note: Studio recording, Moscow, 1950. The Orchard Music

Josef Suk (violin), Violin Concerto in D Major, by W. A. Mozart with Prague Chamber Orchestra, conducted by Libor Hlaváček, YouTube (29 April 2018), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WVySGOTLa5o.

Note: SME (on behalf of Eurodisc)

David Garrett (violin), Violin Concerto in D Major, by W. A. Mozart with Chamber Orchestra of Europe, conducted by Claudio Abbado, YouTube (29 July 2018), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6PS1LvVzLgQ.

Note: ℗ 1995 Deutsche Grammophon GmbH, Berlin Released on: 1995-01-01

Henryk Szeryng (violin), Violin Concerto in D Major, by W. A. Mozart with New Philharmonia Orchestra, conducted by Alexander Gilbson, YouTube (3 June 2019), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WeSCiBRFPkc.

Yehudi Menuhin (violin), Violin Concerto in D Major, by W. A. Mozart with Paris Symphony Orchestra, conducted by George Enescu, YouTube (19 December 2019), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zWuS_DGfCWc.

Note: Recorded 4 June 1932 transferred from Jpn Victor 78s / JD-44/7(2L-374/380)

Ernst Kovacic (violin), Violin Concerto in D Major, by W. A. Mozart with Scottish Chamber Orchestra, conducted by Ernst Kovacic, YouTube (4 March 2020), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tu7Vmxm6QHE.

Henryk Szeryng (violin), Violin Concerto in D Major, by W. A. Mozart with Saarbrucken Radio Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Stanislaw Skrowaczewski, 1978, YouTube (20 May 2021), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n54N1AwfJ68.

Henryk Szeryng (violin), Violin Concerto in D Major, by W. A. Mozart with London Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Karl Böhm, YouTube (23 September 2021), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ekC3knOB9I0.

Note: Live recording, Salzburg, 5 August 1973. Recorded live by Austrian Radio

Salvatore Accardo (violin), Violin Concerto in D Major, by W. A. Mozart with Orchestra Da Camera Alessandro Scarlatti Di Napoli, conducted by Ettore Gracis, YouTube (9 July 2023), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Qs-jnQDOKLM.

Note: Recording of 1962 remastered by Nikolaos Velissiotis. ℗ 1990 Nar International Srl su licenza di Nikolaos Velissiotis