Introduction and Background

In recent years, the CMS/ATMI National Conference has consistently included a variety of presentations concerning online music instruction. Attendees return home each November armed with an assortment of innovative teaching strategies, curricular ideas, questions, and thought-provoking philosophies for online instruction. As teachers of an online theory fundamentals class, we reassess the effectiveness of our own online teaching practices by combining reflections on our classes with our recently-acquired conference perspectives and studies from recent literature. Our self-examination of teaching practices integrates points of view from within our sub-discipline as well as those from other musical sub-disciplines, making our contemplation of online pedagogy overwhelming at times.

In 2013, we decided to take a step back and ask ourselves, “What is online in music instruction?” With so many disparate pieces of information connected to online music teaching and learning available, we realized the need for a single, broad illustration of what is being taught online. This expansive viewpoint would serve two functions: it would succinctly provide a report of what is being done, and it would help contextualize our music theory practices within the larger arena of online music instruction.

This two-part article reports on both macro and micro-perspectives of online music instruction. After a brief review of literature demonstrating the growth and increasingly vast scope of online music instruction, Part I of this article will present the results of two national surveys on online music courses conducted in 2013 and 2016. The section will compare data regarding the nature of recently offered online courses in music and how they are taught. It will identify practices and trends over the three-year period. Part II of this article will offer a case study of our own online Music Theory Fundamentals course at the University of Tennessee-Knoxville. It will provide specific examples of what we have done online, and connect student grades and retention rates relative to decisions we have made while building and modifying the course. The combination of these perspectives will serve as a helpful resource for those interested in online music instruction.

The Growth of Online (Distance) Learning and its Literature

In general, online education continues to grow each year. Elaine Allen and Jeff Seaman’s often-cited study tracking U.S. online courses offered during fall semesters from 2002 – 2011 reported the positive growth rate of students taking at least one online course through the years. In 2002, they found that 9.6% of the total enrollment in degree-granting postsecondary institutions took at least one course online; by 2011, the figure had increased to 32%.1Allen and Seaman, Changing Course: Ten Years of Tracking Online Education in the United States, 36. A more recent study by Allen, Seaman, Russell Poulin, and Terri Taylor Straut found that distance education enrollments had a 7% increase from fall 2012 to fall 2014, and noted that many institutions are increasing the number of distance education programs and are creating new ones even though campus-based and overall enrollments are decreasing.2Allen, Seaman, Poulin, and Straut, Online Report Card: Tracking Online Education in the United States, 13. This study, the thirteenth annual report in a series originally called the Sloan Surveys of Online Learning, refers to “online learning” synonymously to “distance education.” For consistency and simplicity, this article will use the term “online learning” to refer to courses offered partially or entirely online. Judith Bowman’s Online Learning in Music: Foundations, Frameworks, and Practices (2014, 4-7) calls attention to the thorny issue of names associated with online learning in the section entitled “Defining Distance and Online Education: What’s in a Name?” where she references online proportion-based names as defined by the Sloan Consortium and points out NASM’s definition of distance learning: “Distance learning involves programs of study delivered entirely or partially away from regular face-to-face interactions between teachers and students in studios, classrooms, tutorials, laboratories, and rehearsals associated with coursework, degrees, and programs on the campus. Normally, distance learning uses technologies to deliver instruction and support systems, and enables substantive interaction between instructor and student.” (NASM, 78) They observed that in the fall 2014 semester 2,858,792 students took exclusively distance courses while another 2,970,034 students enrolled in at least one distance course.3Ibid, 43. Their reports also asked respondents to express the level of their agreement with the question, “is online education critical to the long-term strategy of your institution?” In 2002, 48.8% agreed, 38.1% were neutral, and 13.1% disagreed; by 2014, 70.8% agreed, 20.6% were neutral and only 8.6% disagreed with the statement.4Ibid, 45. Not only do these results illustrate the growth of online education, but they suggest the changing perception that online learning will continue to be important in the future.

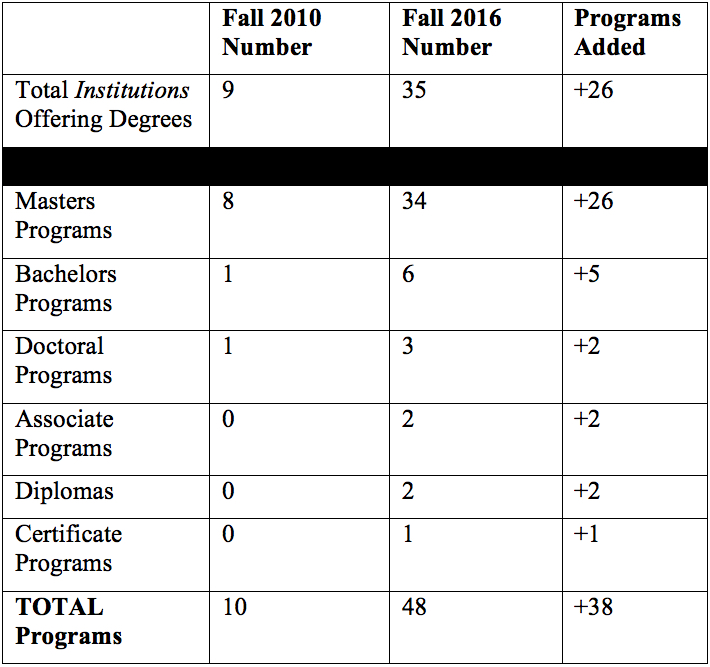

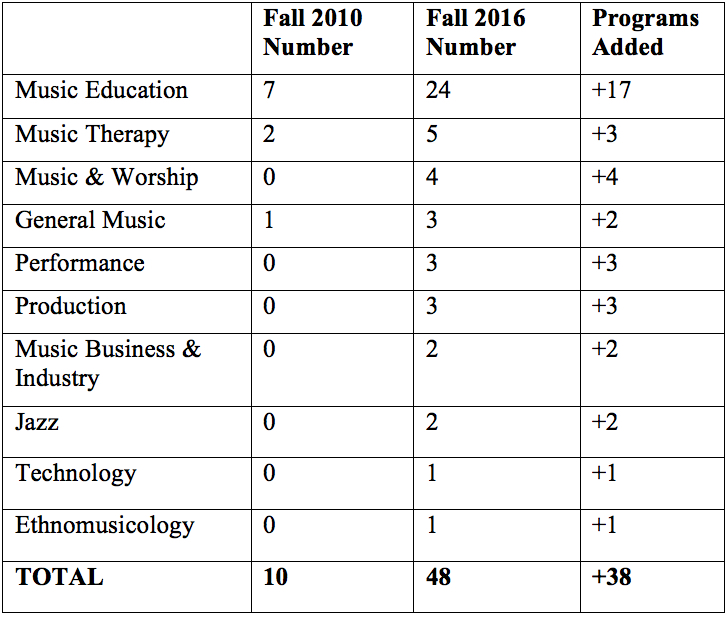

Online learning in music continues to grow as well. The National Association of Schools of Music (NASM) maintains lists of accredited institutions that offer distance learning programs, and their data shows that all degree levels have increased offerings in the past six years (see Table 1a).5Data available from NASM; see https://nasm.arts-accredit.org. We compare 2010 to 2016 because NASM informed us that 2010 was the earliest list available for information on both institutions and degree titles. Their data shows that, though counts for degree types in 2007 and 2013 were not available, in 2007 there were 5 total institutions offering distance learning degrees, in 2010 there were 9, in 2013 there were 15, and in 2016 there were 35. As Table 1a illustrates, thirty-eight new online programs were created in the six-year period from 2010 to 2016, and the most notable increase has been in the number of master’s degrees (i.e. 26). Table 1b provides a comparison of distance learning degree sub-disciplines offered in 2010 and 2016; by far the most common sub-discipline to be taught online remains in music education.

Table 1a: Total Number of NASM Institutions with Online Programs, and Program Levels: 2010 & 2016

Table 1b: Comparison of NASM-Accredited Distance Learning Degree Sub-disciplines, all Degree Levels: 2010 & 2016

Though reports similar to the Allen, Seaman, Poulin, and Straut survey do not currently exist for music, there is certainly increasing interest in online learning, further demonstrated by a variety of articles dedicated to examining specific online curricula and degree programs. Specific curriculum/degree program studies within sub-disciplines provide a window into the types of courses and programs being offered online, suggesting most of them concern music education and music therapy.

Timothy Groulx and Patrick Hernly examined nine online NASM-accredited music education programs6This 2010 article examines 9 online master’s degrees in music education, though NASM reported that only seven music education distance learning degrees existed in 2010. NASM is not sure why this discrepancy in information exists. to “compare a variety of aspects such as curriculum, acceptance information, enrollment numbers, tuition, the type of professors who teach the courses (adjunct or full-time), what types of students take advantage of these online degree opportunities, and other pertinent information.”7Groulx and Hernly, “Online Master’s Degrees in Music Education: The Growing Pains of a Tool to Reach a Larger Community,” 60. Their study provided many details of online program design, such as course types, and did not consider the online degrees as either better or worse than traditional programs. They found that online programs may not be best for every student or professional situation, but they can be important in reaching a broader community of students who may encounter logistical problems enrolling in an on-campus program.8Ibid, 68.

Victoria Vega and Keith Douglas surveyed the “breadth and depth of online learning” in music therapy programs across the United States.9Vega and Douglas, “A Survey of Online Courses in Music Therapy,” 176. They found that most online courses in these programs are in therapy theory and research, and that while many courses include online discussions, assignments, lectures, and video presentations, the “experiential classes” are not as likely to be taught as prominently online as “didactic classes.”10Ibid, 176, 181.

Theano Koutsoupidou studied online education programs by examining them through the perspectives of the instructors teaching in them.11Koutsoupidou, “Online Distance Learning and Music Training: Benefits, Drawbacks, and Challenges,” 247. She interviewed seven instructors from four different countries about their experiences teaching in online programs and courses, and identified important advantages (e.g. programs with diverse student backgrounds and experiences) as well as drawbacks (e.g. online discussion settings not well embraced by students).

Daniel Albert took a phenomenological approach to studying the online graduate music education degree; he interviewed one student enrolled in an online Masters of Music Education (MME) and another in a traditional MME program in effort to observe why the two matriculated students chose their respective degree programs. Among the factors that determined their decisions were professional and financial responsibilities, building relationships with faculty, observed flexibility of the online program, and growth of musicianship.12Albert, “Online Versus Traditional Master of Music in Music Education Degree Programs: Students’ Reasons for Choosing,” 52. Other program examinations exist as well,13See Vogel, Seong-Hi, and Ho-Hyung Cho-Schmidt, "Washington Global University (WGUNIV) German Institute of Music Therapy-Master of Arts-Online-Curriculum," 153-54; Hebert “Five Challenges and Solutions in Online Music Teacher Education;”1-10; and Fung, "Perception of the Need for Introducing Flexible Learning in Graduate Studies in Music Education: A Case Study," 107-120. and it will be important for these types of inquiries to expand to other sub-disciplines as programs in their fields sustain further development.

Recent empirical and theoretical studies centering on online course designs, implementation strategies, and creative pedagogies also suggest growth as well as advance our understanding of what is occurring online. The amount of literature regarding these topics is indeed vast, and readers should begin investigations with Judith Bowman’s 2014 book Online Learning in Music: Foundations, Frameworks, and Practices, a definitive tool when considering the body of research in online music learning. Her broad literature review coalesces a variety of studies connected to the above topics and results in her own grounded suggestions regarding course development, best practices, trends, tools, and techniques.

Within specific sub-disciplines, findings by Pamela Pike and Kristen Shoemaker offer interesting approaches to teaching applied music online. Their 2013 study evaluated the acquisition of sight-reading skills in beginning piano students in two groups: a control (face-to-face) group and an experimental (live video instruction) group. They determined that, though there was no significant difference between the two groups’ improvement levels, the online group was more engaged with the instructor and the content during lessons.14Pike and Shoemaker, “The Effect of Distance Learning on Acquisition of Piano Sight-reading Skills,” 159. Their 2015 work included instructor and student perspectives of teaching and learning piano skills online, providing helpful viewpoints for those considering online applied lessons. While Pike, the instructor, found that teaching online piano lessons brought “a renewed sense of discovery and energy” to teaching, Shoemaker, the student, reported that online lessons provided greater flexibility for her schedule and the technology was not difficult to use.15Pike and Shoemaker, “Online Piano Lessons: a Teacher's Journey into an Emerging 21st-century Virtual Teaching Environment,” 12. Other recommended studies regarding online applied training include Kruse et. al., "Skype Music Lessons in the Academy: Intersections of Music Education, Applied Music and Technology,” 43-60, and Pike, "Improving Music Teaching and Learning through Online Service: A Case Study of a Synchronous Online Teaching Internship,” 227-242.

Keith Dye’s recent study is similar to that of Pike and Shoemaker’s 2013 article, though Dye recorded both student and instructor (music education majors) behaviors during online applied lessons. Results suggested that “instructors in this study chose to use questioning more and modeling less, while students demonstrated less and use verbal responses more than in prior studies when compared to face-to-face lessons.”16Dye, “Student and Instructor Behaviors in Online Music Lessons: an Exploratory Study,” 161.

In the area of music theory, Michael Lively called for consistent evaluation of pedagogical approaches so that fully online music theory classes could provide the same academic experiences as those in a traditional classroom.17Lively, “The Development, Implementation, and Supervision of Online Music Theory Courses,” 1+. His work built “top ten” lists of issues that arise in developing, implementing, and supervising online music theory courses, drawing on his and other instructors’ and administrators’ experiences with online courses.18Other suggested studies regarding online music theory course design include McCandless and Stephan-Robinson, “Video and Podcasting Tools for Blended, Flipped, and Fully-Online Music Theory Courses,” 1-14, and Chong "Blogging Transforming Music Learning and Teaching: Reflections of a Teacher-researcher," 167-181.

In the area of music education, Sharon Lierse’s proposal of using Participatory Action Research methodology to deliver online music and arts education courses included four steps: “planning a change, acting and observing the processes and consequences of change, reflecting on the processes and consequences, and re-planning to start the cycle again.”19Lierse, “Developing Fully Online Pre-service Music and Arts Education Courses,” 29. Other suggested articles regarding general online music education course designs and perspectives include Reese (2013) and Ruthmann and Hebert (2012). Her methodology is certainly applicable to a variety of music courses.

These studies, though a small sample, provide individual snapshots of the types of programs and courses being offered online in various music sub-disciplines. The work of these scholars has facilitated the growth in online music learning, especially in the areas of music education, music theory, and music appreciation. However, we felt the survey comparison could provide a broader perspective of what is presently occurring online.

Current Surveys

Part I: 2013 and 2016 Survey Comparisons

In 2013 and again in 2016, we distributed a survey whose purpose was to discover what music classes were being taught online. In addition to questions about the institution, the survey asked a series of questions about the five online classes that had the highest enrollment or were offered the most often. The participants were free to report on what they considered to be an online class, whether they be hybrid or fully online classes. The results of the two surveys will be described below.

Participants

Invitations to participate in both surveys were sent to Association for Technology in Music Instruction (ATMI) and (National Association of Schools of Music) NASM members. In 2016, we also sent the survey through CMS Surveys to members that identified themselves as interested in online education; we also distributed the survey through various social media venues. In addition, in 2016 we sent special letters of invitation to schools identified as having a strong online education presence. These schools were identified through a search of schools with distance learning degrees on the NASM website, which resulted in the names of 35 schools.20By NASM standards, distance learning degrees must have at least 40% of their requirements delivered through distance learning. (NASM Handbook 2016-17, III.H.3.b) Potential participants were sent an invitation email with a link to the survey. The survey itself was administered through Constant Contact in 2013 and via Qualtrics in 2016.

Results & Discussion

In 2013, there were 58 respondents, while in 2016 there were only 43 respondents. The characteristics of the schools participating were similar: four-year (2013: 83.7%; 2016: 88.4%)21In 2016, the question was split into the number of 4-year institutions (25.6%) and 4-year institutions that had Master and Doctorate degrees (62.8%). public institutions (2013: 47.4%, 2016: 62.8%). In 2016, more schools offered higher degrees than in the earlier survey; 11 schools reported their highest degree was a doctoral degree and 14 reported the highest degree was the master’s degrees in 2016, versus 6 doctoral programs and 10 master’s programs in 2013.

Although the number of respondents was down in 2016, the number of courses reported rose in number; respondents reported 67 online courses in 2013 and 76 classes in 2016. Even though there were more classes, the most basic properties of the courses did not change. Most classes were 3-credit hour classes (2013: 79%, 2016: 72.4%), were 15 weeks in length (2013: 54.2%, 2016: 39.4%), and were offered in the fall, spring, and summer (2013: Fa-29.3%, Sp-24.1%, Su-41.6%, 2016: Fa-27.2%, Sp-26.5%, Su-32.5%). It is interesting to note that the largest number of online classes were offered in the summer, most likely when more students are studying from home or juggling jobs with school. In both years, more classes are at the undergraduate level (2013: 84.3%, 2016: 89.3%), with the largest percentage being lower division undergraduate classes (2013: 80%, 2016: 85.1%).

Some properties of the classes did change, however. While, in general, class sizes remained small (2013: 79.5% had less than 50 students; 2016: 72.4% below 50 students), the percentage of classes with 75 or more students rose significantly from 8.9% in 2013 to 21.1% in 2016. It is unknown whether the number of students in the classes rose because they were offered online or whether the number of online classes rose because the size of the classes grew larger. This question would provide a compelling investigation for future surveys.

Another factor that changed was the type of instructor teaching the classes. The percentage of classes taught by non-tenure track faculty rose from 8% in 2013 to 19.6% in 2016, while the number of classes taught by tenure-track faculty fell by 6% (2013: 54%, 2016: 48%) and the number taught by adjunct faculty dropped by 4.8% (2013: 33.3%, 2016: 28.5%). This change could reflect a more general change in higher education and not just a change in online classes.

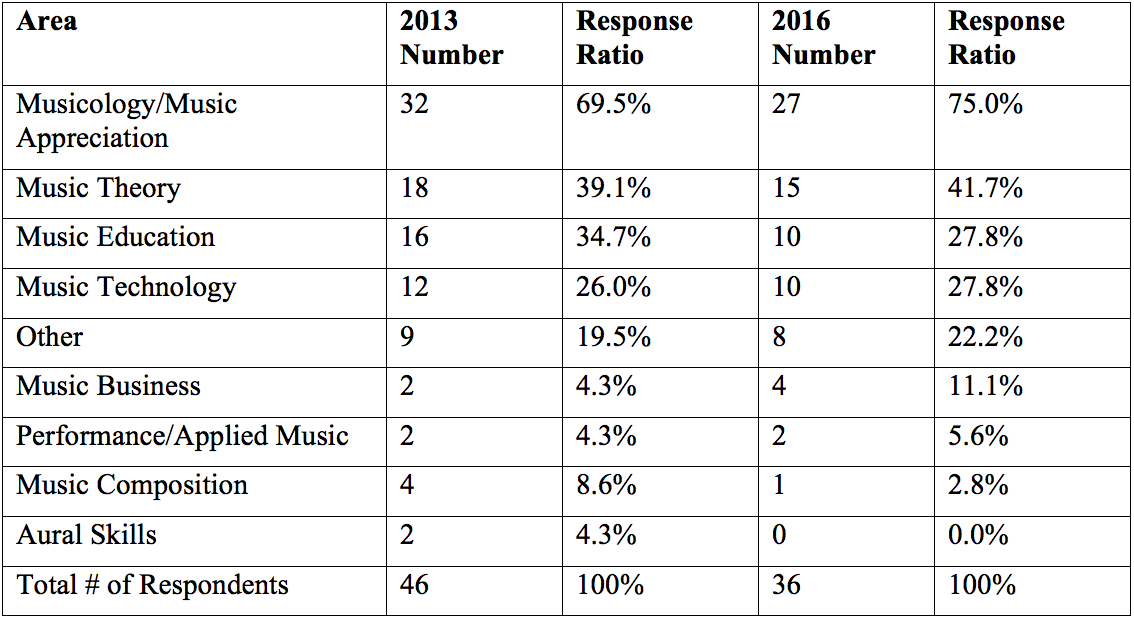

The music sub-disciplines for the most prevalent online courses (see Table 2) did not vary between 2013 and 2016. Most online courses are in musicology/music appreciation (2013: 69.6%, 2016: 75%), music theory (2013: 39.1%, 2016: 41.7%), music education (2013: 34.7%, 2016: 27.8%), and music technology (2013: 26%, 2016: 27.8%). The topics for the classes within these sub-disciplines, however, were more varied in 2016. Titles such as The History of Electronic Music and Video Game Music were added in musicology, Music Theory Analysis for the Educator was added in music theory, and Technology for Music Educators and Practicum in Music Education were added in music education. The most notable changes of titles were in music business classes; in 2013, classes in this area focused on particular computer software programs (i.e., Finale, Sibelius, ProTools), while in 2016 the titles were much more general in nature (e.g., Survey of Music Technology, Expressing Music Through Technology, Digital Music Pedagogy).

Table 2: Areas for Online Courses

Not all sub-disciplines offer online classes, however. While the number of classes in music business rose 100% (from 2 classes in 2013 to 4 classes in 2016), the number of online courses in music composition fell from 4 to 1 and online courses in aural skills became non-existent (i.e., their number fell from 2 to 0). These numbers provide support for the notion that online courses moved away from skills-based topics and moved toward knowledge-based topics.

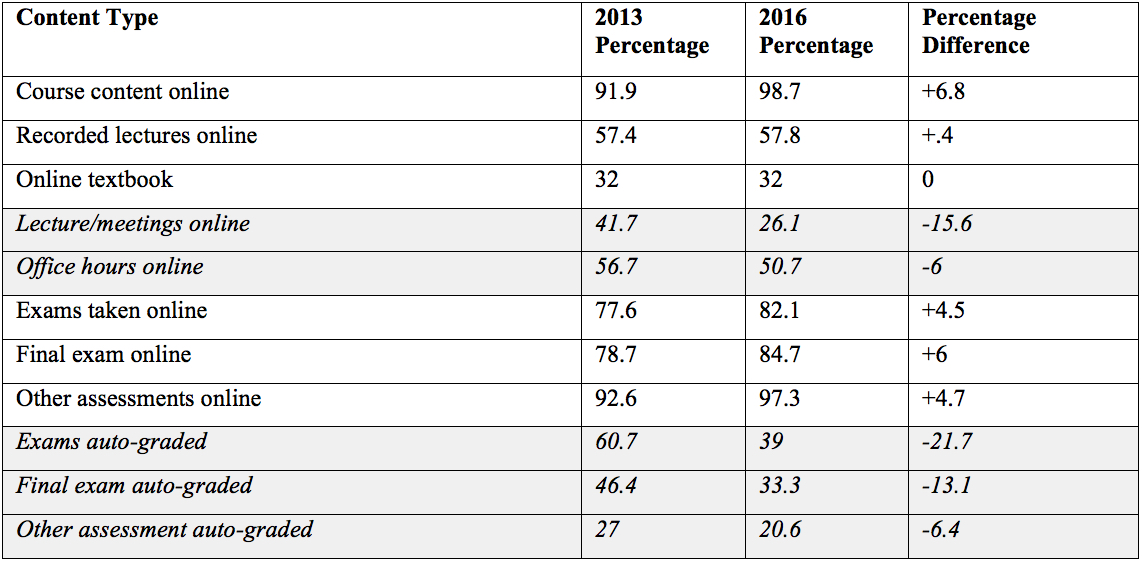

The content of online classes also changed from 2013 to 2016 (see Table 3). Although more course content was presented online (+6.8% difference), the percentage of classes using an online text did not change at all. Online classes also used more online assessments; the percentage of exams, final exams, and other assessments all rose from 2013 to 2016. However, the number of assessments that were auto-graded fell significantly with the largest percentage differences in exams auto-graded (-21.7%) and final exams auto-graded (-13.1%). Either teachers did not like or agree with the computer evaluation or the types of questions given on the exams changed from easily-graded objective questions to more subjective measures, such as essay questions. The percentage of courses with meetings that occurred online also fell by large margins; the percentage of lecture/class meetings fell by 15.6% and the percentage of online office hours fell by 6%. The reasons for this decrease in online meetings is not known, but would be an excellent question for a follow-up survey.

Table 3: Content of Online Courses

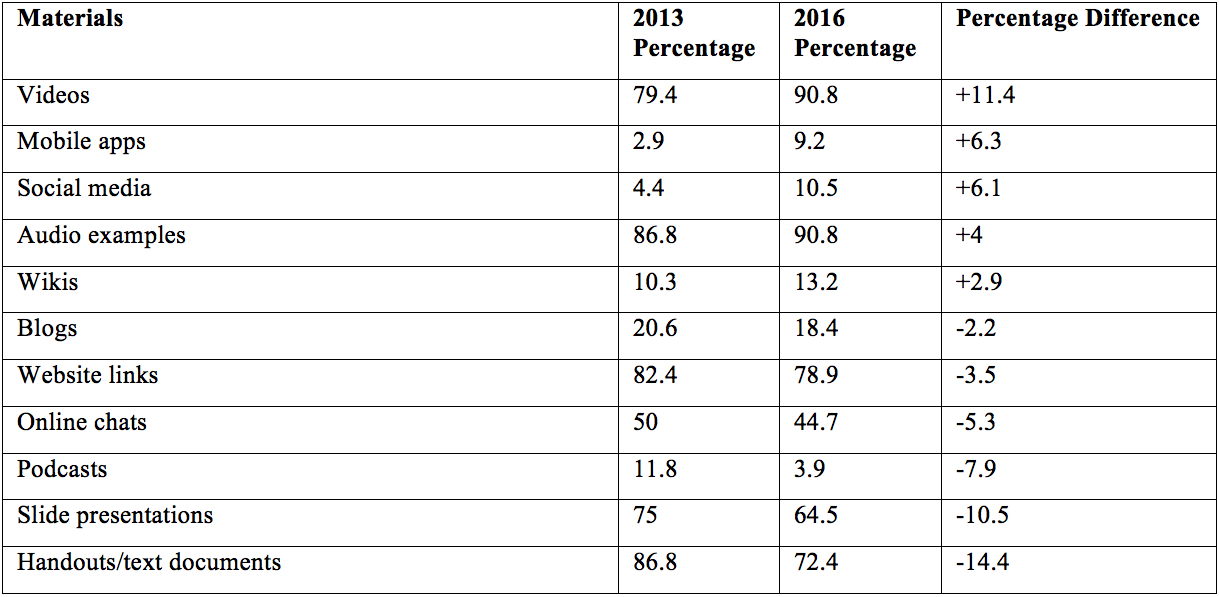

The types of materials used in online classes, in general, did not change from 2013 to 2016 (see Table 4). Videos, audio examples, website links, slide presentations (e.g., PowerPoint, Keynote, and Prezi presentations), and handouts/text documents all remained the most common types of material; well over half of the classes reported using these materials. However, in some cases, there was a large change in the percentage of classes that used these types of materials. The highest increases were in the use of videos (up 11.4%), mobile apps (up 6.3%) and social media (up 6.1%). The largest percentage decreases were in the use of podcasts (down 7.9%); slide presentations (down 10.5%); and handouts and text documents (down 14.4%). The changes in online materials may reflect the increasing popularity of web videos, social media, and mobile devices, and a predilection for more active rather than passive learning.

Table 4: Materials used in Online Course

The development of online courses underwent a significant change in the three years between the surveys. In 2013, 18.8% of online courses were developed by publishers and professional authors. In 2016, this number fell to 4%, with no online classes developed by publishers. Instead, more faculty developed the courses (2013: 78.2%, 2016: 93.3%). It is not known whether the faculty developing the classes are the ones teaching the classes, or whether the developers are tenure track or non-tenure track faculty. It would be interesting to know whether the change in the type of instructors teaching the class is reflected in the authorship of the courses.

The development time for online courses also changed. In 2013, 95.5% of online courses were developed in less than a year, with most classes (45.5%) being written in three to five months. By 2016, the percentage of online courses developed in a year or less fell to 84.9%, with the percentage of courses taking one to two years rising 6.6% and the percentage of classes taking 2 to 3 years rose from 0% to 4.1%. We would think that development time would shrink given there are more development tools available. However, development time might increase given the fact that faculty have other responsibilities and cannot devote large periods of time to this activity.

In general, the surveys showed that online courses did not seem to change drastically during the period between our surveys. The basic properties and types of classes and general class content used have been mostly consistent over the years. However, the types of materials used and the methods of presentation have been refined over time. This has certainly been true for the online course in Music Fundamentals that we have offered at our university.

Part II: A Case Study - Music Theory Fundamentals Online: 2012 – 2016

Brief Background of Music Theory 100 Online

Issues facing our School of Music in 2009 were the impetus for moving our Fundamentals of Music course (Music Theory 100) online. First, the economic downturn of 2008 prompted our College of Arts & Sciences to increase the number of instructional credit hours delivered by tenure-line faculty by 15%. By offering Music Theory 100 fully online, our department could maintain the ability to offer the same number of lower division courses, as well as the upper division and graduate courses needed by our music majors and graduate students, and have tenure-track faculty teach the classes. Second, we believed offering Music Theory 100 online might help us with recruiting and retention. We thought that offering a class online would make our school more enticing to prospective students. We envisioned high school students taking our online class allowing them to become familiar with our school and faculty and assist in the recruitment of these students. We also believe that music theory classes should not be a catalyst for changing or dropping the music major, and we thought that, if students who had never taken theory classes before started these classes earlier, they would have a better chance of staying on schedule to graduate in four years.

We knew that we wanted to put all course content online in a new way; we did not want just pages of text. We also knew that we wanted to have all assessments online and as many as possible auto-graded. The development of our course took over two years and several grants, including one for developmental assistance from our Innovative Technology Center and another to fund a research assistant. By the time the course was first offered, we had all content and assessments online, as well as online office hours using Skype. The course content, presented as slides, included text, images, audio, and animation. The course also included flashcards for drill and practice, as well as quizzes and tests that pulled from nearly 100 question banks containing over 4,000 questions. The following description of this course will not engage topics specific to music theory fundamentals, such as what approach is best for teaching intervals or scales; rather, this case study will concentrate on general course decisions and their potential impact on student achievement.

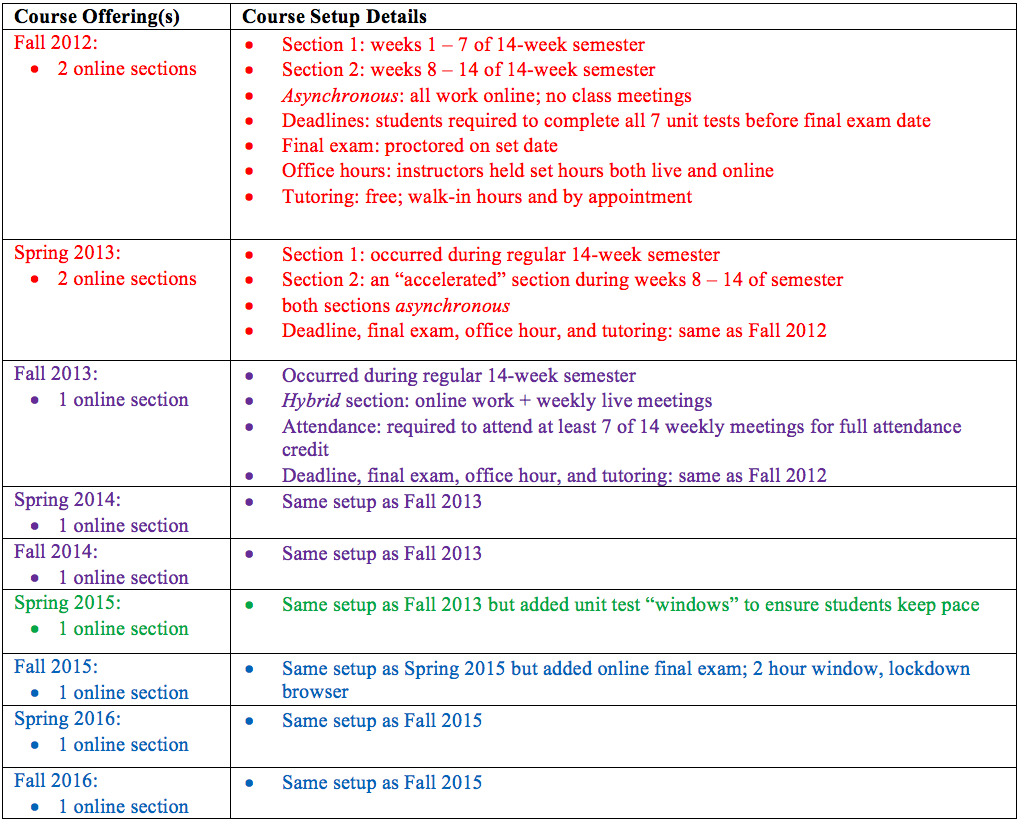

Class Structure: Fall 2012 – Fall 2016

Table 5 provides details regarding the course properties since its first fall offering in 2012. As mentioned, the class was originally conceived to be fully asynchronous as it would be taught as an overload for tenure-line faculty members. During the 2012 – 2013 academic year (AY), it was indeed asynchronous with two online sections per semester; they occurred during both 14-week and 7-week periods (see Table 5 in red). During the asynchronous sections, we saw the students only during office hours and at the final exam; there were no face-to-face (F2F) class meetings. From Fall 2013 through Fall 2014, the course was offered as a single, hybrid section with required attendances and one live meeting per week. In Spring 2015, we altered the course again, adding unit test “windows;” students were required to finish Unit 1 by the end of the first week, Unit 2 by the end of the second week, Unit 3 by the fourth week, etc. The amount of time within the windows expanded as units grew increasingly larger and the topics more involved. Finally, in Fall 2015, we made another adjustment to the course by putting the final exam online.

Table 5: Music Theory 100 Online 2012-2016

Trends and Discussion

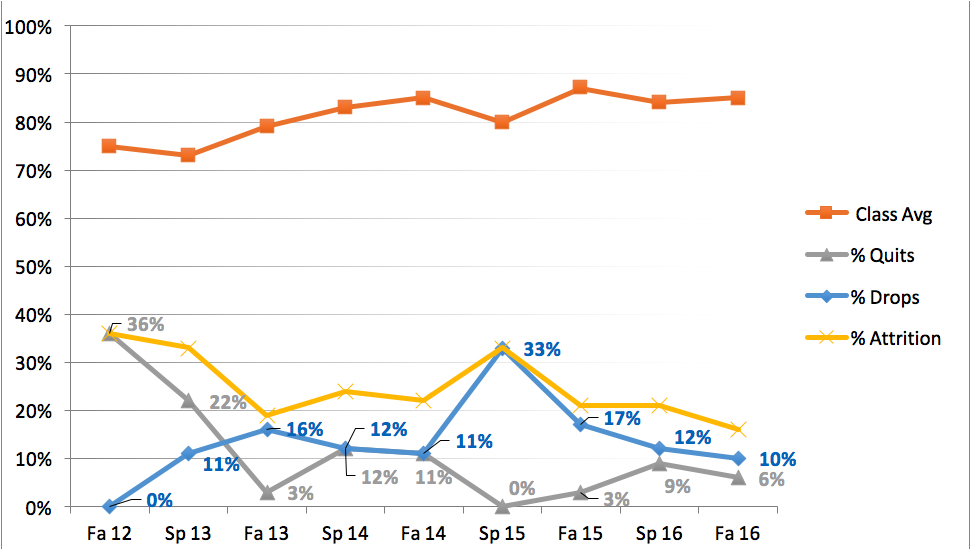

Each adjustment to the class was made to improve the learning experience for our students, and we believe much progress has been made since the course’s initial launch. Each semester we kept track of significant data points to observe trends in retention and success. Figure 1 provides a graphic analysis of grades (i.e., class average), “quits,” drops, and total attrition (i.e., sum of quits and legal drops).22Class averages are calculated using only students who did not drop or quit the course. Using averages of quits would create wide grade discrepancies and standard deviations, as these students could have completed anywhere from 1 – 5 of the unit tests and may or may not have taken the final exam. We define “quits” as students who took the class and did not take the final exam and/or complete 5 of the 7 unit tests, but did not legally drop the course. “Quits” have never passed the course.

Figure 1: Music Theory 100 Trends, 2012 – 2016

By the end of AY 2012 – 2013 we realized the originally-conceived asynchronous setting was not best for our students. Analysis of the sections23Semesters where two online sections occurred used the same instructors, textbook, and course setup. Only the length of the course changed from 15 weeks to 7 weeks. within each semester revealed high rates of attrition (Fall 2012: 36%; Spring 2013: 33%) and lower class grade averages (Fall 2012: 75%; Spring 2013: 73%) relative to concurrent live/traditional Music Theory 100 sections (81% average in both Fall 2012 and Spring 2013 semesters). Most alarming was the amount of “quits” vs. the number of legal drops in the online class. In Fall 2012, no one dropped the course yet 36% of students quit; in Spring 2013, 22% quit while only 11% dropped. Since Music Theory 100 is frequently populated by non-majors, we knew there would be students who dropped the class, but the high percentage of quitters was unsettling, and, coupled with the fact that those students who actually finished the course were in the low to middle C grade range, we knew a change was necessary. The course modifications in Fall 2013 (Table 5), therefore, integrated a modest amount of F2F meetings which we believe helped us move towards higher retention rates (i.e. lower attrition rates). F2F interaction in the now hybrid section, though limited as compared to our traditional live classes, seemed to promote improved communication between student and instructor and resulted in more questions and discussions about the difficulties students encountered. Students were not easily able to become “anonymous” in the hybrid setting.

In their 2013 study, Allen and Seaman stated that chief academic officers at all institutional levels reported that online growth is disrupted by lower retention rates.24Allen and Seaman, Changing Course: Ten years of tracking online education in the United States, 6. This sentiment echoed our concerns in 2013, which prompted the significant change to the course. After a low quit rate in Fall 2013 (3%), we observed several semesters of somewhat higher quit rates (Spring 2014: 12%, Fall 2014: 11%) and the overall attrition rate was still above 20% (Spring 2014: 24%, Fall 2014: 22%). Therefore, we adjusted the course again, adding testing “windows” in Spring 2015 (see Table 5), which proved to be another positive modification to the course since the percentage of “quits” has not gone above 10% since this change.

Allen and Seaman also found that academic leaders had concerns about the need for more student discipline in order to overcome a potential barrier to the growth of online learning.25Ibid, 6. We agree, and our testing windows created periodic milestones in the course and established student accountability for staying on schedule with their work. A final course tweak was made in Fall 2015; at this point we changed to an online final exam. Though we monitor for any potential incidents of academic dishonesty which can arise with an unproctored online exam, we have not witnessed any yet.

When comparing data from our Fall 2012 semester with our Fall 2016 semester, we are confident positive steps have been taken to improve the course. In Fall 2012, communication with students was not effective in conveying the level of self-discipline required in online courses. Therefore, over a third of the students quit, students who should have dropped did not, and the average grade of those who didn’t quit was a C. By Fall 2016, students who should drop the course do, and each semester our drops outnumber our quits. More students are finishing their work and class averages now consistently reside in the B range.

We have also paid attention to student evaluations of the course over time; not only have reporting rates for our evaluations increased since 2012, students are more pleased with the course. Quantitative results from our Fall 2016 semester were generally quite positive (mean scores above 4 in all categories on a 5-point scale) and qualitative feedback was both positive and helpful. One student remarked, “This was an online course, so it was left mostly up to the students to do the work on your own. With that being said we had weekly meetings and the professors taught well and gave me a better understanding of the subject.” Another comment, “This course required a lot of time management in order to succeed,” was encouraging since it suggested that we have made changes that have made the students more aware of their responsibilities as a student in an online course.

Closing Thoughts

These surveys and the analysis of their results provide helpful perspectives on online music teaching and learning. We hope that the case study of our online music fundamentals course offers insights on the types of course organization and policies that work online. We think the next step in the study of online courses should be a more comprehensive inquiry addressing specific teaching strategies, pedagogical frameworks, and curricular approaches that are generating successful online music courses in various sub-disciplines and degrees. Bowman echoes this suggestion:

It would seem that now is the time to reconsider the broader musical, educational, and technological contexts in which online education in music is implemented; to conduct qualitative studies of how people learn in online environments; to investigate specific strategies for online learning in music; and to direct more attention toward development of appropriate instructional models and practical teaching approaches.26Bowman, Online Learning in Music: Foundations, Frameworks, and Practices, 50.

Such a study, as well as a continued self-examination of our own online offerings and blended learning course components, will ensure we are taking the best steps towards more effective education in music.

Notes

1 Allen and Seaman, Changing Course: Ten Years of Tracking Online Education in the United States, 36.

2 Allen, Seaman, Poulin, and Straut, Online Report Card: Tracking Online Education in the United States, 13. This study, the thirteenth annual report in a series originally called the Sloan Surveys of Online Learning, refers to “online learning” synonymously to “distance education.” For consistency and simplicity, this article will use the term “online learning” to refer to courses offered partially or entirely online. Judith Bowman’s Online Learning in Music: Foundations, Frameworks, and Practices (2014, 4-7) calls attention to the thorny issue of names associated with online learning in the section entitled “Defining Distance and Online Education: What’s in a Name?” where she references online proportion-based names as defined by the Sloan Consortium and points out NASM’s definition of distance learning: “Distance learning involves programs of study delivered entirely or partially away from regular face-to-face interactions between teachers and students in studios, classrooms, tutorials, laboratories, and rehearsals associated with coursework, degrees, and programs on the campus. Normally, distance learning uses technologies to deliver instruction and support systems, and enables substantive interaction between instructor and student.” (NASM, 78)

3 Ibid, 43.

4 Ibid, 45.

5 Data available from NASM; see https://nasm.arts-accredit.org. We compare 2010 to 2016 because NASM informed us that 2010 was the earliest list available for information on both institutions and degree titles.

6 This 2010 article examines 9 online master’s degrees in music education, though NASM reported that only seven music education distance learning degrees existed in 2010. NASM is not sure why this discrepancy in information exists.

7 Groulx and Hernly, “Online Master’s Degrees in Music Education: The Growing Pains of a Tool to Reach a Larger Community,” 60.

8 Ibid, 68.

9 Vega and Douglas, “A Survey of Online Courses in Music Therapy,” 176.

10 Ibid, 176, 181.

11 Koutsoupidou, “Online Distance Learning and Music Training: Benefits, Drawbacks, and Challenges,” 247.

12 Albert, “Online Versus Traditional Master of Music in Music Education Degree Programs: Students’ Reasons for Choosing,” 52.

13 See Vogel, Seong-Hi, and Ho-Hyung Cho-Schmidt, "Washington Global University (WGUNIV) German Institute of Music Therapy-Master of Arts-Online-Curriculum," 153-54; Hebert “Five Challenges and Solutions in Online Music Teacher Education;”1-10; and Fung, "Perception of the Need for Introducing Flexible Learning in Graduate Studies in Music Education: A Case Study," 107-120.

14 Pike and Shoemaker, “The Effect of Distance Learning on Acquisition of Piano Sight-reading Skills,” 159.

15 Pike and Shoemaker, “Online Piano Lessons: a Teacher's Journey into an Emerging 21st-century Virtual Teaching Environment,” 12. Other recommended studies regarding online applied training include Kruse et. al., "Skype Music Lessons in the Academy: Intersections of Music Education, Applied Music and Technology,” 43-60, and Pike, "Improving Music Teaching and Learning through Online Service: A Case Study of a Synchronous Online Teaching Internship,” 227-242.

16 Dye, “Student and Instructor Behaviors in Online Music Lessons: an Exploratory Study,” 161.

17 Lively, “The Development, Implementation, and Supervision of Online Music Theory Courses,” 1+.

18 Other suggested studies regarding online music theory course design include McCandless and Stephan-Robinson, “Video and Podcasting Tools for Blended, Flipped, and Fully-Online Music Theory Courses,” 1-14, and Chong "Blogging Transforming Music Learning and Teaching: Reflections of a Teacher-researcher," 167-181.

19 Lierse, “Developing Fully Online Pre-service Music and Arts Education Courses,” 29. Other suggested articles regarding general online music education course designs and perspectives include Reese (2013) and Ruthmann and Hebert (2012).

20 By NASM standards, distance learning degrees must have at least 40% of their requirements delivered through distance learning. (NASM Handbook 2016-17, III.H.3.b)

21 In 2016, the question was split into the number of 4-year institutions (25.6%) and 4-year institutions that had Master and Doctorate degrees (62.8%).

22 Class averages are calculated using only students who did not drop or quit the course. Using averages of quits would create wide grade discrepancies and standard deviations, as these students could have completed anywhere from 1 – 5 of the unit tests and may or may not have taken the final exam.

23 Semesters where two online sections occurred used the same instructors, textbook, and course setup. Only the length of the course changed from 15 weeks to 7 weeks.

24 Allen and Seaman, Changing Course: Ten years of tracking online education in the United States, 6.

25 Ibid, 6.

26 Bowman, Online Learning in Music: Foundations, Frameworks, and Practices, 50.

Bibliography

Albert, Daniel J. “Online Versus Traditional Master of Music in Music Education Degree Programs.” Journal of Music Teacher Education 25, no. 1 (2015): 52-64.

Allen, I. E., and Seaman, J. Changing Course: Ten Years of Tracking Online Education in the United States. Babson Survey Research Group and Quahog Research Group, LLC, 2013. Retrieved from http://sloanconsortium.org/publications/survey/index.asp

Allen, I. A., J. Seaman, R. Poulin, and T. T. Straut. "Online Report Card—Tracking Online Education in the United States. Babson Survey Research Group and Quahog Research Group," 2016. Available at http://onlinelearningconsortium.org/read/online-report-card-tracking-online-education-united-states-2015

Bowman, Judith. Online Learning in Music: Foundations, Frameworks, and Practices. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014.

Chong, Eddy KM. "Blogging Transforming Music Learning and Teaching: Reflections of a Teacher-researcher." Journal of Music, Technology & Education 3, no. 2-3 (2011): 167-181.

Dye, Keith. “Student and Instructor Behaviors in Online Music Lessons: an Exploratory Study.” International Journal of Music Education 34, no. 2 (2016): 161-170.

Fung, C. Victor. "Perception of the Need for Introducing Flexible Learning in Graduate Studies in Music Education: A Case Study." College Music Symposium 44 (2004): 107-120.

Groulx, Timothy J. and Patrick Hernly. “Online Master’s Degrees in Music Education: The Growing Pains of a Tool to Reach a Larger Community.” Update: Applications of Research in Music Education 28, no. 2 (2010), pp. 60-70.

Hebert, David. “Five Challenges and Solutions in Online Music Teacher Education.” Research and Issues in Music Education 5, No. 1 (2007): 1-10.

Koutsoupidou, Theano. "Online Distance Learning and Music Training: Benefits, Drawbacks and Challenges." Open Learning: The Journal of Open, Distance and e-Learning 29, no. 3 (2014): 243-255.

Kruse, Nathan B., Steven C. Harlos, Russell M. Callahan, and Michelle L. Herring. "Skype Music Lessons in the Academy: Intersections of Music Education, Applied Music and Technology." Journal of Music, Technology & Education 6, no. 1 (2013): 43-60.

Lierse, Sharon. “Developing Fully Online Pre-service Music and Arts Education Courses [online].” Victorian Journal of Music Education 1 (2015): 29-34.

Lively, Michael. “The Development, Implementation, and Supervision of Online Music Theory Courses” College Music Society Symposium 56, May 2016. https://doi.org/10.18177/sym.2016.56.itm.11125

McCandless, Gregory R. and Anna Stephan-Robinson. “Video and Podcasting Tools for Blended, Flipped, and Fully-Online Music Theory Courses.” Journal of Music Theory Pedagogy e-Journal 4 (2014): 1-14. Retrieved from https://music.appstate.edu/about/jmtp/ejournal

National Association of Schools of Music. Handbook 2016 – 17. Retrieved from https://nasm.arts-accredit.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2015/11/NASM_HANDBOOK_2016-17.pdf

Reese, Jill A. "Online Status: Virtual Field Experiences and Mentoring During an Elementary General Music Methods Course." Journal of Music Teacher Education 24, no. 2 (2015): 23-39.

Ruthmann, S. Alex and David Hebert. “Music Learning and New Media in Virtual and Online Environments.” In The Oxford Handbook of Music Education, Volume 2, edited by Gary E. McPherson and Graham F. Welch, 567 – 583. New York, NY: Oxford, 2012.

Pike, Pamela D. "Improving Music Teaching and Learning through Online Service: A Case Study of a Synchronous Online Teaching Internship." International Journal of Music Education 8, no. 3 (2015): 227-242.

Pike, Pamela D., and Kristin Shoemaker. “Online Piano Lessons: a Teacher's Journey into an Emerging 21st-century Virtual Teaching Environment, American Music Teacher. 65, no. 1 (2015): 12.

____________. "The Effect of Distance Learning on Acquisition of Piano Sight-reading Skills." Journal of Music, Technology & Education 6, no. 2 (2013): 147-162.

Vega, Victoria P., and Douglas Keith. "A Survey of Online Courses in Music Therapy." Music Therapy Perspectives 30, no. 2 (2012): 176-182.

Vogel, Seong-Hi, and Ho-Hyung Cho-Schmidt. "Washington Global University (WGUNIV) German Institute of Music Therapy-Master of Arts-Online-Curriculum." Nordic Journal of Music Therapy 25, no. 1 (2016): 153-154.