Abstract

Over the past few years, employment opportunities and working conditions for marginalized populations—including women, people of color, and individuals with disabilities—have considerably improved in the United States. While many researchers have specifically examined workplace gender differences in wages, occupations, training, and attrition, there are discrepancies regarding whether women are treated fairly at work. Unfortunately, about a quarter of university faculty contend they have faced gender discrimination (Robst et al., 2003), and women are largely underrepresented in senior university positions (Bakker & Jacobs, 2016), so much work remains to be done.

Despite women working to meet the qualifications necessary to progress in their careers, they still encounter pay-gap inequalities and other barriers related to advancement. Such gender biases may prevent qualified women from advancing to deserved positions (Baumgartner & Schneider, 2010). It is beneficial for those involved in higher education music settings to understand the needs, perceptions, and experiences of all faculty, particularly women.

James A. Grymes

Women’s Perceptions of Advancement Opportunities in Higher Education Music Settings: A Mixed Methods Study

Literature Review

When considering the experiences of women in the workplace and university music settings specifically, some of the most prevalent topics found in the related literature include: success beliefs; institutional failings; social challenges; work-life balance inequities; and bias, discrimination, and human rights violations.

Success Beliefs

Women’s beliefs about the glass ceiling may impact their work engagement and performance (Tanure et al., 2014). A glass ceiling is a “transparent barrier” that prevents women from “rising above a certain level in corporations” (Morrison et al., 1987, p. 13). If women do not believe they have opportunities for advancement, they may experience career burnout, including “exhaustion, cynicism, and reduced professional efficacy” (Balasubramanian & Lathabhavan, 2017, p. 1131).

In academia, agency refers to a faculty member’s beliefs about the potential for advancement and the actions that can be taken to reach those goals (Terosky et al., 2014). Though women aspire to complete research and publication necessary for advancement, the reality of their “overloaded plates” (Terosky et al., 2014, p. 64) includes many other administrative and service tasks. As a result, some decide to stop pursuing advancement while others explore non-academic jobs.

Institutional Failings

Women in higher education may experience gender-specific barriers to career advancement. The percentage of women who advance in higher education remains low compared to men and “the proportion of women declines at each level of the academic hierarchy” (Bessett et al., 2021, p. 49; Johnson, 2017). Women occupy 47% of full-time faculty positions, but are predominately placed in non-tenure track positions (AAUP, 2022). In the United States, “across all academic disciplines, women constitute 24% of full professors, 38% of associates, 46% of assistants, and 56% of lecturers/instructors” (Monroe et al., 2014, p. 419). Despite increasingly earning more advanced degrees than men, women may not be “holding positions with higher faculty rank, salary, or prestige” (Johnson, 2017, p. 6).

Twenty-three percent of female faculty have indicated they do not experience the same opportunities for advancement as their male colleagues with similar experience and performance levels, and 28% of women in academia have reported they have not been promoted nor received advancement opportunities strictly because of their gender (Marken, 2022). Women experiencing this holding pattern of prohibitive opportunities for advancement may be impacted by demographic inertia. This refers to the slow process of faculty turnover since many full professors are men and most often constitute the hiring body for new faculty, perpetuating the cycle (Laursen & Austin, 2020).

Academic intuitions may also fail to implement equitable recruitment, retention, and promotion processes (Laursen & Austin, 2020). Too often, academics express frustration of ambiguity over unclear paths and a lack of criteria for advancement, which lead to “expectations [that] did not always match reality” (Gardner, 2013, p. 359). Boyd et al. (2010) described the tenure process as “confusing and contradictory” (p. 11) with unrealistic expectations for teaching, research, advising, and a lack of opportunity to collaborate with senior faculty.

Social Challenges

Positive mentorship is a consistent contributing factor to the success of women (Grant, 2000); however, there is a lack of quality mentorship available for women seeking academic career advancement (Bergonzi et al., 2015; Boyd et al., 2010; Driscoll et al., 2009; Grant, 2000; Terosky et al., 2014). This lack of collegial support impedes understanding of the work necessary for career advancement (Terosky et al., 2014) and may contribute to unclear tenure expectations (Driscoll et al., 2009).

Women tend to have fewer networking opportunities than men (Hennekam et al., 2020; Macarthur et al., 2017), increasing feelings of isolation (Boyd et al., 2010). Less networking opportunities for women may even lead to a lack of support for their other female colleagues (Macarthur et al., 2017, p. 88). Howe (2009) wrote that “women pay a price for joining academia because they become estranged from each other and distance themselves from ‘women’s lived experience’ as they adopt the language of academia” (p. 178).

Women may also experience backlash for self-promoting (Rogus-Pulia et al., 2018). Women who strive to advocate for themselves professionally, or proactively explore ways to strengthen their professional credentials, may experience disapproval or negative consequences from peers (Hennekam et al., 2020).

Work-Life Balance Inequities

While there tends to be an overall “lack of institutional support for faculty with any family responsibilities” (Boyd et al., 2010, p. 8.), women in academia may experience the additional challenge of not being taken seriously if they are balancing professional work with caring responsibilities (Hennekam et al., 2020). Boyd et al. (2010) reported that the “academy’s hostility towards female faculty members as caregivers – particularly as mothers – persists” (pp. 15-16), with a clear indication that institutions may be strongly unsupportive of women with family or dependents. Though women often intend to return to work following the fulfillment of family responsibilities, the interruption of their career can create anxiety as women question whether the required level of performance ability can be maintained or resumed (Bennett, 2008).

While women’s childbearing years tend to overlap with opportunities for advancement, men tend to gain momentum during this same period of their lives (AAUW, 2022; Macarthur et al., 2017). Armenti (2004) reported that women “hid their desire to have children…hid maternal desires to meet an unwritten profession standard that is geared toward the male life course,” dubbed as the “hidden pregnancy phenomenon” (p. 219). Some women decide not to have children at a time when “their male peers are emerging” (Macarthur et al., 2017, p. 85) or change their career goals entirely (Bennett et al., 2018).

In addition to challenges with caregiver responsibilities outside of work, women experience larger service obligations at work which can limit advancement opportunities (Bessett et al., 2021; Boyd et al., 2010; Johnson, 2017; Terosky et al., 2014). Women and people of color are asked to accept more service roles to satisfy the need for greater committee representation, limiting time to publish and conduct research (Bradley et al., 2017). Women tend to be assigned to more difficult committees, often bear more of the workload on committees, and show more concern regarding the impact of the decisions made by the committees than men (Bessett et al., 2021). This “service trap” (Terosky et al., 2014, p. 65) may hinder opportunities for publication and promotion, thereby threatening one to remain at a lower rank or position.

Bias, Discrimination, and Human Rights Violations

Despite calls for gender equity, little change has occurred in academia (Rogus-Pulia et al., 2018). Isaac et al. (2009) reported that gender bias was the observed difference between evaluations of men and women who demonstrated “identical qualifications” (p. 1440), while Carson (2001) reported that student evaluations demonstrate more gender bias against women professors than men. Gender bias in evaluations for research funding and awards may also disadvantage women (Rogus-Pulia et al., 2018). A 2022 AAUW report noted that “women are disproportionately published less and receive less credit than male authors” (para. 7).

Women also continue to experience professional wage disparity. While this gap may be narrowing, Midkiff (2015) calculated only an increase of “one-half of 1%” (p. 378) from 2000 to 2010. For women in higher education, this pay gap may be augmented, particularly if they are in caregiving roles. Crittenden (2002) discussed the “mommy tax” phenomenon, where female caregivers experience a lifetime “average of $659,139 in lost wages,” in addition to other costs of caregiving such as being passed up for promotions, having to “use up sick leave and vacations, reduce workloads to part-time, and in many cases even quit their paid jobs altogether” (p. 91). Crittenden (2002) stressed that this tax may be more pronounced for women who are well-educated and seeking tenure.

Women in workplaces with a high male-dominated ratio may encounter greater instances of sexual harassment (Robst et al., 2003; Schmalenberger & Maddox, 2019). Dey et al. (1996) reported that female victims of sexual harassment tend to be single women of higher rank, have fewer female colleagues, and work at public institutions. As the proportion of women at the institution increases, the possibility of being a victim of sexual harassment decreases, suggesting that the treatment of women becomes better as more women are hired (Dey et al., 1996).

Some faculty members who have encountered sexual harassment do not share or report their experience for fear of “disrupting their career and day-to-day life” (Kirkner et al., 2022, p. 209). They may also choose not to report for fear that peers may side with the male colleague, a phenomenon that Manne (2018) called himpathy – the “flow of sympathy away from female victims toward their male victimizers” (p. 23). Schmalenberger and Maddox (2019) found that 43% of female brass players who experienced sexual harassment in the workplace said it negatively affected their performance ability, caused changes to their playing, and oftentimes led to giving up playing their instrument altogether. This results in an unfortunate and unnecessary loss of the unique work and innovation of female musicians in the profession (Hisama, 2021).

Prior research documents the different experiences women face in the workplace, including in academia. However, there appears to be a lack of information related to how women in higher education music settings specifically perceive their experiences. This study aims to fill the gap in the literature related to women’s perspectives of faculty advancement in higher education music settings. It is important that university stakeholders develop an understanding of faculty members’ perceived experiences to best determine faculty needs, support structures, professional development opportunities, and suitable evaluation techniques intended for workplace advancement that is free from bias or discrimination.

The purpose of this convergent mixed methods research study was to examine the experiences of collegiate music faculty and determine whether factors such as barriers, capabilities, acceptance, work-life balance, advancement, and success beliefs influence perceptions of advancement opportunities in higher education music settings. We addressed the following research questions:

- What are the perceptions of collegiate music faculty related to their positions and experiences working in higher education?

- In what ways do faculty believe they are supported in their collegiate music positions and in what ways do they feel support could be improved?

- Is there a statistically significant difference between women’s perceptions of their experiences in collegiate music positions and those of men?

- Is there a statistically significant relationship between the perceptions of collegiate music faculty members’ experiences and their advancement opportunities (i.e., title/rank/role) and if so, what is the nature and strength of the relationship?

Methodology

Participants

Participants in this study included music faculty employed at higher education institutions in the United States who were part-time, adjunct, or full-time, as well as those who held a variety of academic ranks and titles, including tenured, tenure-leading, and non-tenure track positions. We distributed the survey instrument to 2,917 members of the College Music Society (CMS) and 1,690 members of the National Association for Music Education (NAfME) who identified as teaching collegiate music. We received a total of 126 responses--100 valid data sets used in the quantitative analysis and 77 participant responses to the open-ended questions for qualitative analysis. The sample size was large enough to meet assumptions for the statistical analyses we performed; therefore, results are generalizable to the overall population of collegiate music faculty.

Respondents described their gender identity as male (35.0%), female (62.5%), or non-binary/third gender (2.5%), and their biological sex as male (36.4%) or female (63.6%). Though we would like to capture the experiences of participants who identify as non-binary, the small number of participants in this group did not yield any statistically significant results in the quantitative analysis, so we focused our examination on biological sex rather than gender identity for this study.

Equipment and Materials

Based on a review of the literature, an examination of various related questionnaires, and feedback generated from a panel of experts in collegiate music settings, we created a modified version of the Advancement Opportunities Questionnaire (Moosa, 2016) that we named the Faculty Opportunities for Advancement in Music (FOAM) Questionnaire [available as a supplemental file].

Using a Likert-type rating scale, 28 items were scored with a range from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree and an option for “unable to answer.” The questionnaire intended to measure the extent that advancement, barriers, support, acceptance, capabilities, success beliefs, and work-life balance contribute to music faculty members’ perceptions of their advancement opportunities in higher education institutions. In addition, participants were asked to provide open-ended written responses to questions regarding advancement, perceptions of support, and experiences in higher education based on their individual characteristics.

Assessment of the Survey Instruments

To measure the instrument’s accuracy by testing its content validity, we reviewed the related literature, examined existing questionnaires that gathered data similar to the information needed for the current study, and modeled survey items after previously existing questions. In addition, a panel of experts in higher education music positions reviewed the FOAM questionnaire to determine content and face validity.

After receiving IRB approval, we conducted a pilot test before distributing the questionnaire to a small group of higher education music faculty. In the final distribution of the survey, before performing additional statistical analyses, we checked reliability using the participants’ data to confirm the questionnaire performed as intended. Using SPSS, the calculated Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.842, suggesting a relatively high internal consistency. Since the reliability estimate encompasses all items on the questionnaire without considering the subgroups of each of our constructs or the interaction among them, the score may be underestimated.

Procedure

The Marshall University Institutional Review Board granted approval to conduct the study (ID #1861621-1). Participants received an email distributed through CMS and NAfME containing a link to the FOAM Questionnaire in Qualtrics. CMS and NAfME distributed the survey during February and March of 2022 to all members of the organizations that identified as currently employed as a music faculty member in a higher education institution. We ensured that participants’ identities were kept confidential and anonymous in reporting results.

Integration

We chose a mixed methods research design to provide additional support to each methodology (Greene et al., 1989). An important element in mixed methods research is the point of interface--the point at which the two methodologies are integrated--offering support for each strand. In this study, the point of interface occurred at interpretation where all results were merged together. Integrating the results at the interpretation stage allowed us to answer the research questions more thoroughly than could have been accomplished with only one methodology (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2011).

Validation Strategies

We employed triangulation and disconfirming evidence to enhance the validity of this project. Triangulation occurred by utilizing qualitative and quantitative data to answer research questions and by having each researcher code the qualitative data separately (Flick, 2018). We also reported disconfirming evidence, a process of including contrasting information, to ensure we included all participant views. A reflexivity statement is included below to enhance the validity of the accounts reported in this project (Creswell, 2013; Stake, 1995).

Reflexivity

All three researchers identify as cisgender women. While we each have experienced varying levels of sexism in our workplaces and personal interactions, we have also experienced support and encouragement from male-identifying peers and mentors. As such, the coding of the data, which all three researchers executed, may have included bias. We worked to acknowledge and eliminate bias, including codes and quotes from all respondents with equal measure to present the lived experiences of all participants.

Data Analysis and Results

After obtaining participant survey responses online through Qualtrics, we uploaded data to SPSS for analysis. The Nebraska Evaluation and Research (NEAR) Center assisted in analyzing the data. The qualitative component of this convergent mixed methods research study included four open-ended response questions at the conclusion of the questionnaire. Responses to each question were moved to four independent Word documents. Margins to the left and right were altered to allow space in the left-hand margin to list codes and space in the right-hand margin to identify quotes that were highlighted in the text. Each researcher used the same documents and independently coded the data. In vivo codes, which are words of the participants, were used as often as possible. Final codes were uploaded independently by each researcher to a shared spreadsheet. Codes were reduced across all three researchers and then collapsed—a process completed synchronously by all researchers. We then grouped the codes to create themes.

Research Question 1

Quantitative Results

To determine collegiate music faculty members’ perceptions of their positions and experiences working in higher education, participants responded to 28 items on the FOAM Questionnaire. We categorized seven items as Barriers, Support, and Acceptance (BSA) (items 7, 8, 10, 14, 23, 24, 25), six items as Capabilities and Success Beliefs (CAS) (items 1, 4, 5, 21, 22, 26), six items as Work-life Balance (WLB) (items 11, 12, 15, 16, 17, 20), seven items as Advancement (ADV) (items 2, 3, 6, 9, 13, 27, 28), and two Unique items that did not fit our constructs above, but that we felt would yield relevant data for the study (items 18, 19). We calculated descriptive statistics for each of the 28 items and reported the data in frequency distributions [available as a supplemental file]. We also calculated descriptive statistics for demographic information and reported the data in frequency distributions [available as a supplemental file].

Qualitative Results

Participants responded to the first and fourth open-ended questions to answer the first research question. First, participants were asked to “Please describe your own personal experiences with advancement opportunities, rank, title, and promotion related to the position(s) you have held in higher education music settings.” The themes that emerged included Support and Advancement obstructions.

Support. Several respondents described feeling well-supported by their institutions and encouraged toward advancement. One participant stated, “I feel that it is easy for me to take advantage of opportunities…to advance my career and gain promotion,” while another said, “I have felt well-supported by my area in this endeavor.” One found their “progress was smooth,” while another felt “lucky in a couple of instances” because they “happened to be in the right place at the right time.” Another found the “advancement processes were rigorous but smooth.”

Aspects that seemed to aid advancement included clear promotion and tenure guidelines along with mentoring support. One respondent stated, “Tenure and promotion policies and procedures are clear and fairly straightforward in my department. Formal mentoring is available as are opportunities for research release before and after tenure.” Financial assistance has also proven beneficial to some faculty working toward advancement with “greater support afforded to pre-tenure faculty than tenured faculty.” Encouragement from senior faculty can offer additional levels of support to new faculty. As one participant stated, “I had a lot of support from Senior [sic] colleagues outside music education, across the country and within my institution.” Another said, “I felt guided along the way and had confidence I would be promoted.”

Advancement obstructions. While expectations for promotion and tenure are clearly defined at some institutions, other faculty have encountered ceilings to advancement, unclear guidelines for promotion and tenure, and inequities in salary and workload. One respondent stated their “experience with service work, particularly administrative responsibilities, has not been positive,” while another stated, “You have to conform, you can’t be an individual. If you don’t fit the mold, it is hard to succeed.”

Many institutions hold faculty “to brutally high expectations relative to the support.” One respondent stated, “I will likely delay or possibly forgo having more children at this time.” Another shared, “Women are much more likely to be given service and ‘secretarial’ work than men.” In contrast, a different woman added, “I can definitely see women working harder than men to attain promotion. The biggest challenge is in the service category, where we are overburdened.” One participant mentioned, “I have had senior male faculty members ask me to take on work outside of the scope of my position (usually part of theirs) and use the line ‘but this will help you earn good grace towards tenure.’”

The many demands placed on faculty can also hinder advancement. As one participant stated, “The main challenge currently is a constant stream of administrative work and teaching overloads that highly limit my research time. This, plus being continually asked and sometimes coerced to participate on multiple committees, has absolutely hindered my advancement toward full professor.” Another noted, “The current culture seems to now rely more and more upon adjunct professors to do the important artistic and technical educating,” yet place a ceiling on advancement “due to [a] limited number of full-time ‘slots.’”

The fourth open-ended response question on the FOAM Questionnaire asked participants to “Please describe any positive or negative experiences you have had in your higher education music position(s) based on your individual characteristics (i.e., age, race, ethnicity, gender identity, biological sex, sexual orientation, relationship status, religious affiliation, etc.).” The themes that emerged from this question were Inequity, Human rights violations, Disheartening, and Positive experience.

Inequity. Several respondents commented on inequities, mainly gender inequity, faced in their respective positions. One woman commented, “When my department chair asked me to help out at a conference, he told me to go home and ask my husband about it first.” Another participant recounted an experience observing a student teacher and shared, “The (male) band director said to me ‘why on earth did they hire a woman for this job?’ He then told me that he would no longer accept student teachers from our (very large and flagship) program.” One respondent stated, “It was startling to …see the stark differences in load (particularly service) between my male and female colleagues.” This was echoed by other participants, one of whom pointed out that women are “disproportionately voted into service positions” while men are “disproportionately given leadership positions.” Another participant wrote that women are often “expected to carry the emotional load for all that students bring to the table” and are “punished in very tangible ways (time) for being empathetic, good listeners, and empowering” to students.

Another stated, “Sexism has been a negative experience my whole life. As a woman, you have to do twice as much to get half as far as a man. Men fail upward while women can succeed only to fail because of age and gender.” Another said, “My male colleagues sometimes give less credit to the contributions of my female colleagues in meetings.”

The issue of inequity went beyond gender as one participant mentioned that a colleague assumed she “would be weak, pliable, easily controlled” as the only black faculty or staff member in her department. An Asian female also stated, “There has been a baked-in expectation of both excellence and deference on my part, (i.e., that I won’t demand anything, or complain).” Another participant felt that their sexuality kept them from advancement, stating, “I felt that colleagues unknowingly and possibly knowingly used my sexuality as a hindrance to fulfilling my goals.”

Human rights violations. A group of participants mentioned experiences that would be considered violations of their human rights within a workplace. Inappropriate comments from male faculty toward female colleagues were the most mentioned offenses, though other violations were also included. One woman stated, “My direct supervisor is a bully and treats women as though we were back in the 50s. It is disheartening. I am the only female faculty member in my area. I have to keep tight records and have reported two incidents to HR. Nothing has been done in terms of apologies or consequences.” Another participant was told she would not be considered for department chair because she was female, while another woman recounted one of “many” experiences, stating, “I once had a colleague tell me that a male student in my class…was being rude because I wasn’t being assertive enough. ‘Sometimes you just need to take them from behind,’ he said.”

In addition to sexual harassment experienced by women in higher education, one participant pointed out, “When I was on maternity leave, my department still contacted me to ask me to do work.” Another said, “Colleagues with power over my review have used the wrong pronouns and basically asked me to apologize to them for their mistakes. It took nearly 4 [sic] years to have access to a gender-neutral bathroom in my building. During a debrief after a peer observation, I was taught how to give an aggressive, masculine handshake to ‘more effectively dominate’ interactions with local teachers.”

Marital status and male-to-female power dynamics were also discussed. One man shared, “When pre-tenured, I got divorced and a senior faculty member told me I should not remarry until AFTER [sic] I got tenure.” Another faculty member pointed out that she was “bullied by male full professors” when serving as department head.

Disheartening. In addition to inequities and human rights violations experienced by faculty in the workplace, disheartening byproducts of a career in higher education can range from delaying having children, putting off advancement to have children, and challenges faced when seeking a healthy work-life balance. Both men and women appear to face these issues. For example, one man stated, “My career advancement was definitely delayed during the time I had young children. There was no support for young fathers…I had to figure it out as I went along.”

Additional difficulties faced by female faculty working with some male colleagues also emerged. One respondent stated, “The double bind applies: making a contribution or voicing an opinion (particularly a strong one) means I’ll be regarded as intelligent and competent but unlikable. Or I can conform to gender expectations and be soft and kind–and then be presumed to not be very intelligent or competent. Additionally, I’m aware that I am never, ever allowed to raise my voice or demonstrate emotion…I’m supposed to smile all the time, which I’m not good at. It’s exhausting.” Another mentioned their “complaint is with a male colleague who continues to exert his male supremacy over the women who work much harder and more effectively than he.”

General disrespect and unfair stereotypes toward faculty may also undermine the confidence of faculty. One respondent stated, “I am non-binary, gender non-conforming, and have to constantly ‘prove’ my expertise, whereas expertise is expected from my male colleagues.” A “small, white woman” pointed out that many people don’t believe she deserves “the same level of respect as others.”

Some faculty feel unseen or that they need to hide components of their personal lives. One participant stated, “I have lied and referred to my partner that passed as my brother,” while another person stated they have “been mocked and belittled” by colleagues because of their Christian faith. Another mentioned being “looked down on” due to their religious affiliation, while an older white woman stated, “I am invisible to some of my colleagues.”

Though feelings of invisibility or irrelevance can be challenging to overcome, one male participant pointed out that there exists “an overwhelming feeling of negativity towards white males in today’s professional world. Academia has become so saturated with leftist ideals they have almost ‘overcompensated’ for injustices done to others. There is now more emphasis placed on age, race, and ethnicity than values, experience, and mutual respect.” Another participant pointed out unfairness in teaching assignments due to demographic factors such as being “expected to teach 8:00 am classes” because they “do not have any children” and are also “expected to serve on committees over the summer” because they live locally.

Positive experience. While negative experiences of faculty members comprised the majority of responses, several had positive things to say about advancement and their overall experiences in higher education music settings. One faculty member had several “raises based on equity initiatives,” while another stated their institution and administration are “adamant about inclusion,” so they “haven’t seen anyone negatively affected.” An openly gay professor has not received “any negative experiences” with their LGBTQ research interests and their “advocacy work has been fully supported” within the department.

One person of color mentioned that “parents of students are often surprised to see a black person in my position,” which they see as a positive as they can be “a role model to minority students.” Another respondent pointed out that they “have always had positive experiences” and “have been so lucky” to work with “truly wonderful people.”

The remaining positive experiences come from white men who acknowledged their privilege and how that has allowed them to advance in their careers. One stated, “Since I present as a cis-het white male, I rarely encounter anyone doubting my qualifications.” Another mentioned that while they “benefit from subtle privileges for white (passing) and male heteronormative individuals” at an institution where “equity actions are present and effective…there is still work to do.” One participant said, “As a white, straight, cisgender male, I have been fortunate to not face any negative experience in earning or carrying out my position” and recognizes “the privileges that come with it.” Another male respondent said that although he has “reasonably good interpersonal skills” and is a “pretty good match for any job or team” he “definitely” gets “that privilege bump.”

Research Question 2

To determine how faculty believe they are supported in their collegiate music positions and how they feel support could be improved, we qualitatively analyzed participant responses to the second and third open-ended questions in the FOAM Questionnaire. The themes that emerged from analysis of the second question were Encouragement to grow and Good collegial environment, while themes from the third question included Institutional failings and Workload.

Encouragement to grow. Many faculty commented on various institutional supports in achieving advancement. Financial support to pursue research interests was seen as an important asset to several participants, with “faculty mentorship” also proving beneficial to several respondents seeking promotion and tenure. Faculty have also benefited from professional development training offered by their institutions or at specialized off-campus conferences. “Clear policies for how faculty are evaluated for promotion and tenure” was also seen to support faculty, along with administrators providing “space and time to grow” into positions.

Good collegial environment. A positive work environment with encouraging colleagues and administrators seemed beneficial to participants. Respondents appreciated “Support from…departmental colleagues” and “Encouragement to improve.” One participant mentioned that their “institution has a very good collegial environment” while another said they have been “respected as a professor.” Some found their administration open to “changes in curriculum and assessment” and provided them with “autonomy to…work.” Faculty were particularly vocal about how important it was to feel that the work they do is valued not only by their peers, but their superiors as well.

Institutional failings. While some faculty were able to highlight ways in which they have been supported, those experiences are inconsistent across institutions of higher education in music settings. Some faculty feel “limited due partially to the lack of funds available,” and others would like “release time to engage in research opportunities” to advance in their careers.

Participants also pointed to a lack of leadership and diversity in their departments. One respondent who is the only untenured female in her area said, “My research, though nationally and internationally recognized, is not seen as important in my area. I am given ‘secretarial’ tasks…while other tenured male faculty assign themselves tasks that bring in the most recognition, esteem, or reward. I really just want to be compensated fairly for the work I do and treated like an equal among my colleagues.” Failings in leadership also make for a hostile work environment for some, as multiple women in one institution have filed complaints against a male “colleague who has continually harassed and taken inappropriate action against women” only to have seen him “protected by his…male Dean” and “never brought up in a formal manner. He is now tenured, still behaving in this manner.” Faculty would like to see “more oversight and involvement on the part of…administrative leadership.”

Workload. Another challenge faculty face is the workload associated with positions in higher education. Some feel more can be done in “lessening service for POC and female faculty.”

Adjunct faculty are particularly concerned about their respective workloads and the uncertainty of their positions. One wrote, “It is difficult to feel a sense of community and ownership completely over my work if I am told every year that I may not be returning.” Another mentioned that their job requires they “continue to maintain multiple memberships in national organizations, continue to participate in professional development, and invest in” their own artistic performance without adequate compensation.

Some feel that “administrative duties are constantly falling on faculty” and that there are often “not enough faculty” for school’s needs. One participant wrote that “tenured faculty must not hold tenure-leading faculty to higher standards with regard to research and creative activities, service, and collegiality.” Another said, “Senior faculty do not take on much service work, so it falls on the tenure-track members struggling to get research done and cover more course preps.”

Research Question 3

To determine whether a statistically significant difference exists in the perceptions of women compared to men in higher education music settings, we conducted a one-way multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) to compare mean scores of constructs within the FOAM Questionnaire reported by women (n = 63) and men (n = 37). We chose a MANOVA analysis because it can handle variables that are somewhat correlated. The dependent variables or fixed factors were the construct groupings (BSA, CAS, WLB, ADV, and Unique), and the independent variable was biological sex. Excluding missing data, our total sample size was n = 100.

Prior to conducting the MANOVA, we checked to ensure assumptions were met. Although we did not violate assumptions for BSA, WLB, ADV, or the Unique groupings, the assumption of homogeneity of variance was violated for CAS and, therefore, for the overall FOAM mean score. To accommodate, we used the corrected model when examining the tests of between-subjects effects.

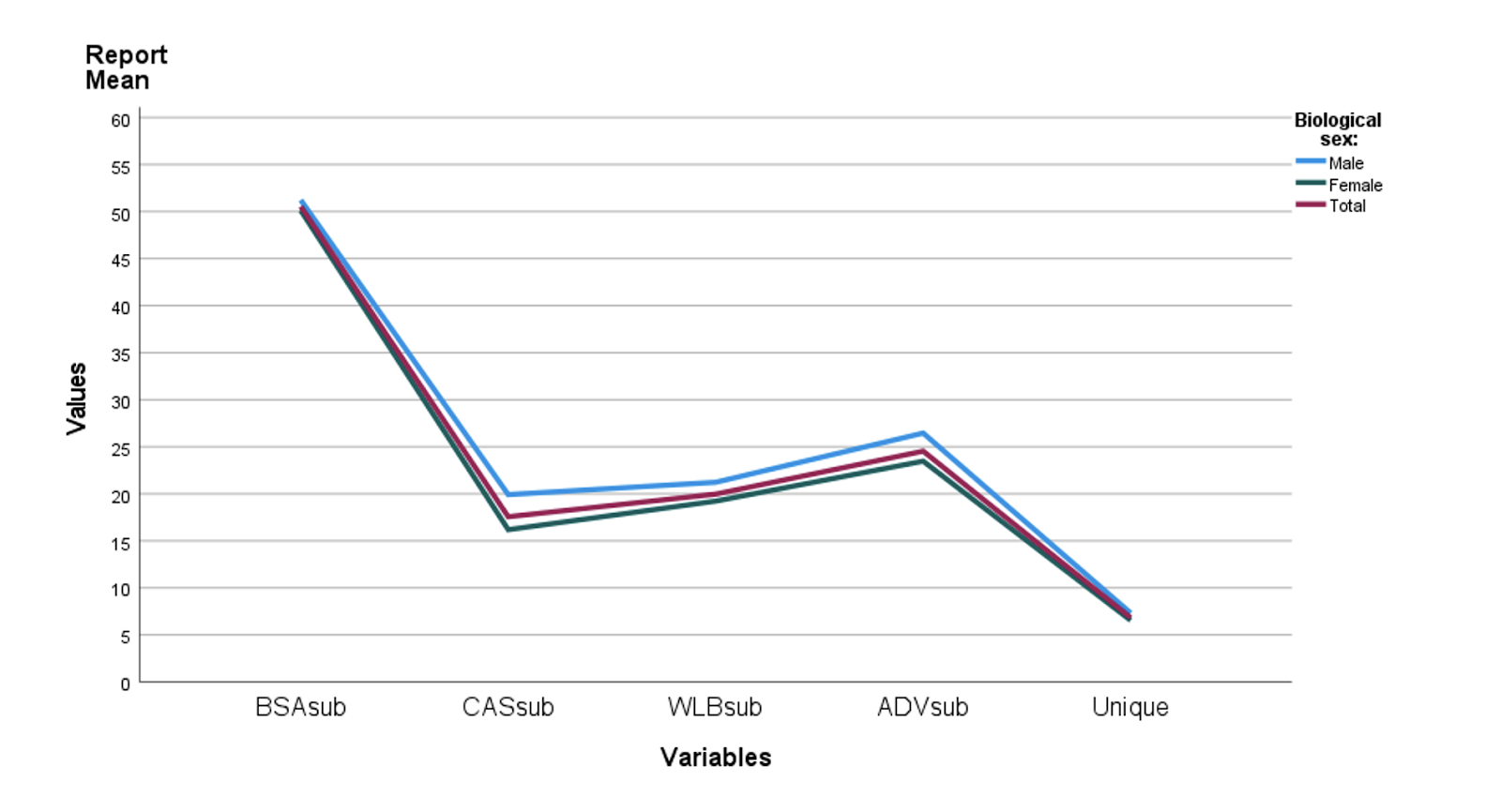

Results of the one-way MANOVA revealed statistically significant differences between men and women in their responses to the FOAM Questionnaire (Wilks’ lambda = 0.802, F (6.0, 93.0) = 3.834, p = 0.002) with an effect size of partial eta squared = 0.198, indicating a large effect (Huck, 2012). Figure 1 illustrates the overall mean differences between men and women in their responses to the FOAM Questionnaire.

Figure 1

Overall Mean Differences of FOAM by Biological Sex

Because the MANOVA revealed a significant difference, we conducted tests of between-subjects effects as a post hoc investigation to determine where the differences among our dependent variables occurred. Examination of the corrected model using the p < 0.05 level of significance revealed significant results within the constructs of Capabilities and Success Beliefs [F (1, 98) = 16.894, p < 0.001, η² = 0.147], Work-Life Balance [F (1, 98) = 4.626, p = 0.034, η² = 0.045], and Advancement [F (1, 98) = 12.270, p < 0.001, η² = 0.111]. However, there were no significant differences between the responses of men and women within the Barriers, Support, and Acceptance [F (1, 98) = 1.261, p = 0.264] or Unique constructs [F (1, 98) = 1.933, p = 0.168]. Figure 2 illustrates the mean differences of FOAM constructs by biological sex.

Figure 2

Mean Differences of FOAM Constructs by Biological Sex

Research Question 4

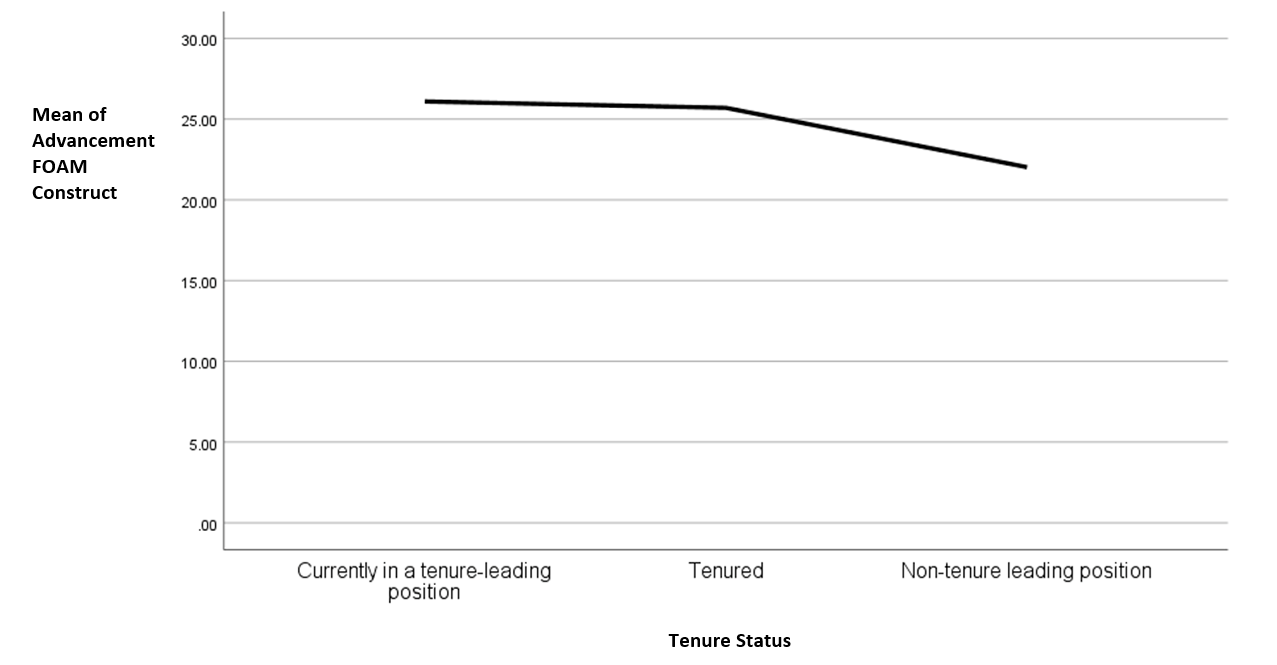

To determine the nature and strength of the relationship between the perceptions of collegiate music faculty members’ experiences and their advancement opportunities (i.e., title/rank/role), we calculated a Pearson’s correlation coefficient. Using participant responses from the FOAM Questionnaire, we compared the variables of tenure status obtained from the demographic portion of the survey (currently in a tenure-leading position, tenured, or currently in a non-tenure leading position) and responses to items within the Advancement construct. Using SPSS, we first examined the scatter plot to ensure the relationship was not curvilinear or influenced by outliers that would skew the results. The correlation was -0.375 (p < 0.01, two-tailed), indicating a moderate, statistically significant negative linear relationship between tenure status and advancement perceptions. Figure 3 illustrates the negative correlation between tenure status and faculty perceptions of advancement.

Figure 3

Correlation Between Tenure Status and Faculty Perceptions of Advancement

Discussion

In this convergent mixed methods study, we examined the perceptions of collegiate music faculty toward their opportunities for advancement. We determined a statistically significant difference between the perceptions of men and women based on their responses. Women’s perceptions of their opportunities for advancement were statistically more negative, with significant results within the constructs of Capabilities and Success Beliefs, Work-Life Balance, and Advancement. However, no statistically significant differences were found between men and women within the constructs of Barriers, Support, and Acceptance and Unique. We also found a statistically significant negative linear relationship between tenure status and self-reported perceptions of advancement opportunities. Based on analysis of participant open-ended responses, results indicated that collegiate music faculty members’ descriptions of their personal experiences with advancement include overall themes of Support, Advancement obstructions, Inequity, Human rights violations, Disheartening, and Positive experience. When asked how participants have been supported and how support could be improved, the themes that emerged were Encouragement to grow, Good collegial environment, Institutional failings, and Workload.

Demographic Implications

Data were collected in 2022 with the largest group of participants between 30-39 years old (31%). They included many participants who have worked in higher education for five years or less (23%), with the greatest number of respondents working in their current position for less than five years (41.3%). Therefore, the concerns addressed by the collegiate music faculty in this study appear to be current and relevant. Though demographic data encompassed faculty members throughout all academic career stages, many participants can be considered junior faculty. In other words, concerns with gender-related opportunities for advancement in academia are not issues contained to past generations–they continue to be the issues of today.

Interestingly, most participants were female (59.5%), and the number of respondents decreased incrementally with each advancing age group. This statistic contradicts a report by the National Association of Schools of Music (NASM) that claimed a faculty ratio of 68% males to 32% females among accredited schools (Overland, 2016). It is possible that, of all people who received the invitation to participate in the study, women felt most compelled to reply based on the topic. The results led us to wonder why there were not more women who participated with more years of experience, who represented older age groups, and with more advanced titles or positions. For future studies, it may be worth exploring how many people–particularly women–are leaving academia and not coming back, and why. Perhaps there are experiences we could not capture in the snapshot of this study because those voices already departed higher education.

Additionally, most respondents were in non-tenure earning or non-tenured positions (60.3%) compared to those in tenured positions (34.9%). Therefore, of the total participants in this study, most were younger women in the early stages of their careers in higher education who have been hired into non-tenure track positions or who have not yet advanced to tenured positions. Our conclusions echo previous findings that women are more likely to be hired into non-tenure leading roles (AAUP, 2022; Monroe et al., 2014; Johnson 2017), less likely to advance if hired into a tenure-leading role (Bessett et al., 2021; Bakker & Jacobs, 2016), and perhaps denied opportunities for advancement due to their gender, despite having similar experiences and performance abilities as men (Marken, 2022). Although many participants belonged to these demographics, there were nonetheless statistically significant findings with a large effect size. Hence, the results of this study are generalizable to the wider population of higher education music faculty.

Need to Promote a Positive Work-Life Balance

Concerns with work-life balance yielded a statistically significant mean difference between the responses of men and women in this study. Several participants wrote that challenges within their higher education music positions made it difficult to balance work and family responsibilities, care for dependents, or to even become a parent. Existing literature supports the concern that collegiate environments fail to provide adequate support for maternity leave (Maxwell et al., 2019) and family responsibilities (Boyd et al., 2010), resulting in negative performance ability (Bennett, 2008) and decisions by some to change their career goals entirely to be caretakers (Bennett et al., 2018; Crittenden, 2002) or to not have children at all (Macarthur et al., 2017).

Based on the results of this study, it also appears that women and minorities are unfairly and disproportionately assigned heavier service responsibilities, overloads in teaching, and experience a lack of scholarly or research support compared to men. These findings are congruent with prior research that suggests minorities, including women, are overburdened with service responsibilities (Bessett et al., 2021; Boyd et al., 2010; Johnson, 2017; Terosky et al., 2014) and lack financial support for research (Gardner, 2013). Since, in most university settings, a successful record of research and scholarly activity is recognized as a leading contributor towards advancement, men may hold more of an advantage toward promotion and tenure over women who do not have the time and support to conduct research (or other scholarly or creative activity) due to their busier teaching schedules and service work. Also, it appears as though more women are hired into non-tenure leading positions–with more teaching responsibilities, less research, and fewer pathways toward promotion–while men are more likely to be hired into tenure-leading positions. Therefore, universities can improve the advancement opportunities of women by ensuring that men and women are hired at an equal ratio to both non-tenure track and tenure-track positions, as well as ensuring an equitable distribution of service assignments, teaching load, and research support.

Financial impacts within higher education, including the elimination of tenure-track lines (Bergonzi et al., 2015; Finkelstein, et al., 2017) can make it difficult to find the work-life balance necessary to achieve advancement. Faculty can feel like they are expected to do increasingly excellent work with decreasing amounts of compensation and support. Budget cuts, loss of staff and faculty lines, and lack of teaching support for faculty who go on leave of absences place additional burdens on the faculty who remain. As financial trends within higher education demonstrate increasingly less promise for improvement in the future, workload will likely continue to increase for everyone.

Demand Zero Tolerance for Workplace Sexual Harassment and Discrimination

Though some participants reported positive experiences regarding their advancement opportunities, most responses were overwhelmingly negative. Of the participants who indicated they felt supported in their pursuit or achievement of advancement, many described their career progression as happenstance and “have been so lucky,” “lucky compared to others,” “lucky to be supported by men,” or that they just “happened to be in the right place at the right time.” This description of success as a matter of luck might suggest that the status quo is unlucky for women and that it is more common not to feel supported by men in the workplace.

Other reports of positive experiences appeared to come from white, heterosexual men who “benefit from subtle privileges,” “rarely encounter anyone doubting [their] qualifications,” and “definitely” get “that privilege bump.” This seems to imply an awareness among men that their success in academic advancement may be boosted by their gender, race, and sexual orientation. It also suggests an implicit acknowledgement that advancement in higher education is more difficult for others who are not like them. Laursen and Austin (2020) agreed that the “old boys’ network” is a “barrier woven into the fabric of academic workplaces” (p. 6) and can limit career advancement for women (Grant, 2000; Macarthur et al., 2017). When such men advance in rank and title to senior positions, is it possible they help perpetuate the advancement of other men who share their characteristics?

Results from this study indicated that inappropriate comments from male faculty toward female colleagues appeared to be the most common offenses, a finding supported by previous literature (Loots & Walker, 2015). Prior research suggests that a higher ratio of men in the workplace leads to greater instances of sexual harassment and discrimination (Dey et al., 1996; Robst et al., 2003; Schmalenberger & Maddox, 2019). Therefore, it may be important for universities to apply hiring practices that ensure a balanced, equitable ratio between men and women.

A Call to Action

Higher education institutions may discriminate against women more than in other professions (Robst et al., 2003) due to the slow process of faculty turnover, as higher-ranking positions are dominated by men (Laursen & Austin, 2020). Because women’s experiences in academic music settings with professional exclusion, bullying, discrimination, sexual harassment, and assault are not often brought to public awareness (Hisama, 2021), collegiate music departments may be of a disproportionally high risk for sexual assault (Jacobs, 2013). Attempts to bring such negative incidents to light in efforts to make change are not frequently met with success. Indeed, one woman in our study said that when she reported instances of bullying, “nothing has been done in terms of apologies or consequences.” Experiencing sexual harassment or assault can negatively impact performance ability and lead women towards abandoning the profession (Hisama, 2021; Schmalenberger & Maddox, 2019).

Though some efforts have been made in recent years to help with concerns such as wage disparity, improvements in correcting the pay gap have been largely negligible (Midkiff, 2015). While equal pay is one area where there is room for improvement, so much more also needs to be done. Women should be compensated fairly and treated without discrimination, bias, and harassment in the workplace. As Kuhn (1987) pointed out, discrimination is often not related to wage and can include differences in benefits and workplace treatment. Therefore, solely examining wage disparities is unlikely to encompass most discrimination women believe they encounter on the job.

Based on the results of this study, steps that collegiate stakeholders can take to improve working conditions include: executing hiring practices that guarantee an equitable ratio of men to women faculty among tenure-leading and non-tenure leading positions, setting clear guidelines for advancement, encouraging mentor support and positive networking opportunities, offering balanced financial assistance for research and scholarly work that leads toward promotion, ensuring equitable pay and workload between men and women holding comparable positions, and enforcing zero tolerance for sexual harassment or other human rights violations by taking timely, appropriate, necessary, and visible action. Training and professional development may be needed for those involved to become aware of women’s experiences and understand how to promote unbiased conditions effectively. Only through cooperative efforts of everyone in higher education music settings can workplace environments for all be improved.

References

American Association of University Professors (AAUP). (2022, November 3). Data Snapshot: Full-Time Women Faculty and Faculty of Color.

American Association of University Women (AAUW). (2022, September 25). Fast Facts: Women Working in Academia. https://www.aauw.org/resources/article/fast-facts-academia/

Armenti, C. (2004). May babies and post tenure babies: Maternal decisions of women professors. Review of Higher Education, 27(2), 211-231. https://doi.org/10.1353/rhe.2003.0046

Bakker, M. M., & Jacobs, M. H. (2016). Tenure track policy increases representation of women in senior academic positions but is insufficient to achieve gender balance. PLoS One, 11 (9): e0163376.

Balasubramanian, S. A., & Lathabhavan, R. (2017). Women’s glass ceiling beliefs predict work engagement and burnout. Journal of Management Development, 36(9), 1125-1136. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMD-12-2016-0282

Baumgartner, M. S., & Schneider, D. E. (2010). Perceptions of women in management: A thematic analysis of razing the glass ceiling. Journal of Career Development, 37(2), 559–576.

Bennett, D. (2008). A gendered study of the working patterns of classical musicians: Implications for practice. International Journal of Music Education, 26(1), 89-100.

Bennett, D., Macarthur, S., Hope, C., Goh, T., & Hennekam, S. (2018). Creating a career as a woman composer: Implications for music in higher education. British Journal of Music Education, 35(3), 237-253.

Bergonzi, L., Yerichuk, D., Galway, K., & Gould, E. (2015). Demographics of tenure-stream music faculty in Canadian post-secondary institutions. Intersections (Toronto. 2006), 35(1), 79-104. https://doi.org/10.7202/1038945ar

Bessett, D., Jenkins, L. D., Jones, K. C., Koshoffer, A., Peplow, A. B., Sadre-Orafai, S., & Weinstein, V. (2021). Women's perceptions of explicit and implicit criteria for promotion to full professor. The Journal of Faculty Development, 35(1), 49-56.

Boyd, T., Cintrón, R., & Alexander-Snow, M. (2010). The experience of being a junior minority female faculty member. Forum on Public Policy: A Journal of the Oxford Round Table 2:1–23.

Bradley, D., Yerichuk, D., Dolloff, L. A., Galway, K., Robinson, K., Stark, J., & Gould, E. (2017, January). Examining equity in tenure processes at higher education music programs: An institutional ethnography. In College Music Symposium (Vol. 57). The College Music Society.

Carson, L. (2001). Gender relations in higher education: Exploring lecturers’ perceptions of student evaluations of teaching. Research Papers in Education, 16(4), 337–358. https://doi-org.libproxy.unl.edu/10.1080/02671520152731990

Crittenden, A. (2002). The price of motherhood: Why the most important job in the world is still the least valued. Macmillan.

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among the five approaches (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2011). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Dey, E. L., Korn, J. S., & Sax, L. J. (1996). Betrayed by the academy: The sexual harassment of women college faculty. Journal of Higher Education, 67, pp. 149-173

Driscoll, L. G., Parkes, K. A., Tilley‐Lubbs, G. A., Brill, J. M., & Pitts Bannister, V. R. (2009). Navigating the lonely sea: Peer mentoring and collaboration among aspiring women scholars. Mentoring & tutoring: Partnership in learning, 17(1), 5-21.

Finkelstein, M. J., Conley, V. M., & Schuster, J. H. (2017). Whither the faculty? Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning, 49(4), 43-51.

Flick, U. (2018). Triangulation. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of qualitative research (5th ed., pp.444-461). SAGE.

Gardner, S. K. (2013). Women faculty departures from a striving institution. Between a rock and a hard place. The Review of Higher Education, 36(3), 349-370. DOI: 10.1353/rhe.2013.0025

Grant, D. E. (2000). The impact of mentoring and gender -specific role models on women college band directors at four different career stages (Order No. 9966225). Available from ProQuest One Academic. (304608713). Retrieved from https://www.libproxy.uwyo.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/impact-mentoring-gender-specific-role-models-on/docview/304608713/se-2

Greene, J. C., Caracelli, V. J., & Graham, W. F. (1989). Toward a conceptual framework for mixed-method evaluation designs. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 11(3), 255-274.

Hennekam, S., Macarthur, S., Bennett, D., Hope, C., & Goh, T. (2020). Women composers’ use of online communities of practice to build and support their careers. Personnel Review, 49(1), 215-230. https://doi-org.libproxy.uwyo.edu/10.1108/PR-02-2018-0059

Hisama, E. M. (2021). Getting to count. Music Theory Spectrum, 43(2), 349-363.

Howe, S.W. (2009). A historical view of women in music education careers. Philosophy of Music Education Review 17(2), 162-183. https://www.muse.jhu.edu/article/366957.

Huck, S. W. (2012). Reading Statistics and Research (6th ed.). Pearson Education.

Isaac, C., Lee, B., & Carnes, M. (2009). Interventions that affect gender bias in hiring: A systematic review. Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 84(10), 1440.

Jacobs, P. (2013). Music students may be subject to a disproportionally high rate of sexual abuse by teachers. Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved September 28, 2022 from https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2013/07/30/could-music-students-be-more-risk-sexual-misconduct-professors

Johnson, H. L. (2017). Pipelines, pathways, and institutional leadership: An update on the status of women in higher education. American Council on Education.

Kirkner, A. C., Lorenz, K., & Mazar, L. (2022). Faculty and staff reporting & disclosure of sexual harassment in higher education. Gender and Education, 34(2), 199-215.

Kuhn, P. J. (1987). Sex discrimination in labor markets: The role of statistical evidence. American Economic Review, 77, pp. 567-583.

Laursen, S., & Austin, A. E. (2020). Building gender equity in the academy: Institutional strategies for change. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Loots, S., & Walker, M. (2015). Shaping a gender equality policy in higher education: Which human capabilities matter? Gender and Education, 27(4), 361-375.

Manne, K. (2018). Down girl: The logic of misogyny. Oxford University Press.

Macarthur, S., Bennett, D., Goh, T., Hennekam, S. & Hope, C. (2017). The rise and fall, and the rise (again) of feminist research in music: ‘What goes around comes around.’ Musicology Australia, 39, 73–95.

Marken, S., (2022, March 29). 28% of women in academia say gender limits their advancement. Gallup.

Maxwell, N., Connolly, L., & Ní Laoire, C. (2019). Informality, emotion and gendered career paths: The hidden toll of maternity leave on female academics and researchers. Gender, Work & Organization, 26(2), 140-157.

Midkiff, B. (2015). Exploring women faculty’s experiences and perceptions in higher education: The effects of feminism? Gender & Education, 27(4), 376–392 https://doi-org.libproxy.unl.edu/10.1080/09540253.2015.1028902

Monroe, K. R., Choi, J., Howell, E., Lampros-Monroe, C., Trejo, C., & Perez, V. (2014). Gender equality in the ivory tower, and how best to achieve it. PS: Political Science & Politics, 47(2), 418-426.

Moosa, M. (2016). The retention of women from a leadership perspective in a higher education institution. (Unpublished Master’s thesis) [University of South Africa]. http://uir.unisa.ac.za/handle/10500/23144

Morrison, A. M., White, R. P., White, R. P., & Van Velsor, E. (1987). Breaking the glass ceiling: Can women reach the top of America's largest corporations? Pearson Education.

Overland, C. (2016). Gender composition and salary of the music faculty in NASM accredited universities: 2000–2014. College Music Symposium, 56. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26574424

Robst, J., VanGilder, J., & Polachek, S. (2003). Perceptions of female faculty treatment in higher education: Which institutions treat women more fairly? Economics of Education Review, 22(1), 59. https://doi-org.libproxy.unl.edu/10.1016/S0272-7757(01)00056-5

Rogus-Pulia, N., Humbert, I., Kolehmainen, C., & Carnes, M. (2018). How gender stereotypes may limit female faculty advancement in communication sciences and disorders. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 27(4), 1598-1611.

Schmalenberger, S., & Maddox, P. (2019). Female brass musicians address gender parity, gender equity, and sexual harassment: A preliminary report on data from the brass bodies study. Societies (Basel, Switzerland), 9(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc9010020

Stake, R. (1995). The art of case study research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Tanure, B., Neto, A.C., & Mota-Santos, C. (2014). Pride and prejudice beyond the glass ceiling: Brazilian female executives’ psychological type. Revista de Ciências da Administração, 16(39), 210-223.

Terosky, A. L., O'Meara, K., & Campbell, C. M. (2014). Enabling possibility: Women associate professors’ sense of agency in career advancement. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 7(1), 58–76. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035775