Abstract

The water protectors of the Standing Rock Sioux captured public attention with their opposition to the Dakota Access Pipeline. Yet their actions are only the most recent in a long history of indigenous resistance to resource extraction and treaty violations on native land. Often these struggles have involved indigenous music. In this article, I compare two folk songs, “Our Vinland” by the neo-Nazi band, Prussian Blue, and “Treaty” by the Haudenosaunee Iroquois vocalist, Joanne Shenandoah. I argue that these songs respectively express the current resurgence of settler colonial nativism and the indigenous spirit of resistance to it witnessed at Standing Rock.

On Politics, Music, and Indigeneity

To some scholars, music may seem far removed from politics. Many political scientists relegate music to background context or exclude it from politics altogether. Mainstream definitions of politics typically emphasize political institutions, electoral processes, and rational, self-interested decision making. By comparison, musical sounds engage a broader range and deeper level of human experiences, including affective experiences, bodily movements, and visceral responses. These extra-rational features of music can–and do--motivate people to act politically. However, the political effects of music are not easily controlled or measured. This is partly because music flows across the various borders that mark categories and identities, including groups, nations, and peoples. Although these features may make music seem marginal in mainstream politics, they also constitute its political power. Coercive regimes have used music in state-sponsored cultural projects to manipulate mass publics into sub- or unconscious conformity and compliance. Historically oppressed groups have used it to disrupt politics-as-usual, mobilize political support, and transform political norms and practices. To exclude music from the study of politics is, then, to overlook an important aspect of political communication.1Love, “Politics and Music.”

Politics, as I have already suggested, is productively defined as reaching beyond government institutions and electoral processes to include the arts and culture, especially music. Music, in turn, is far more than an aesthetic object created for receptive listeners. Christopher Small refers to “musicking” to convey “what humans are actually doing when they ‘music.’2Quoted in Laurence, “Music and Empathy,” 14. Small defines “musicking” as follows: “To music is to take part, in any capacity, in a musical performance, whether by performing, by listening, by rehearsing or practicing, by providing material for performance (what is called composing), or by dancing.”3Quoted in Ibid. The shift from music (noun) to musicking (verb) highlights how musical practices participate in relations of knowledge and power. When musicking is understood in cultural-political context, the relevant questions become not whether music is political, but how it is political and why some still regard it as non-political.

I came to the study of music and politics via Jürgen Habermas when I noticed his tendency to employ musical metaphors at crucial junctures in his theory of public discourse. Some of those metaphors are: cacophony, dissonance, harmony, resonance, symphony, and especially, voice.4On Habermas’s musical metaphors, see Love, Musical Democracy, ch. 2. Habermas uses musical metaphors to bridge the gaps between the voices of subcultural (and wild(er)) publics and the rational(ized) systems of capitalist markets and the administrative state. By metaphorically invoking music, Habermas implicitly concurs with Iris Young on the need to pluralize modes of political communication to counter processes of “internal exclusion.”5Young, Democracy and Inclusion, 53-57. Internal exclusions refer to cultural and structural norms that define the terms of public discourse in ways that privilege some groups and dismiss, ignore, or even silence others. Young’s primary target was the tendency of deliberative democrats (like Habermas) to privilege rational argument, a mode of public discourse historically associated with educated, propertied, white males in western democracies.6 Habermas, The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere. To counter this tendency and facilitate cross-cultural understanding, she proposed three additional and complementary modes of public discourse: greeting, rhetoric, and story-telling. Young includes music in her discussion of rhetoric, and mentions that “chanting and singing for a cause” were among her greatest joys of democratic participation and collective solidarity.7 Young, Democracy and Inclusion, 13. Reading Habermas with Young, I saw how his musical metaphors revealed the internal exclusions of his theory of rational communication and prefigured a more inclusive public discourse.

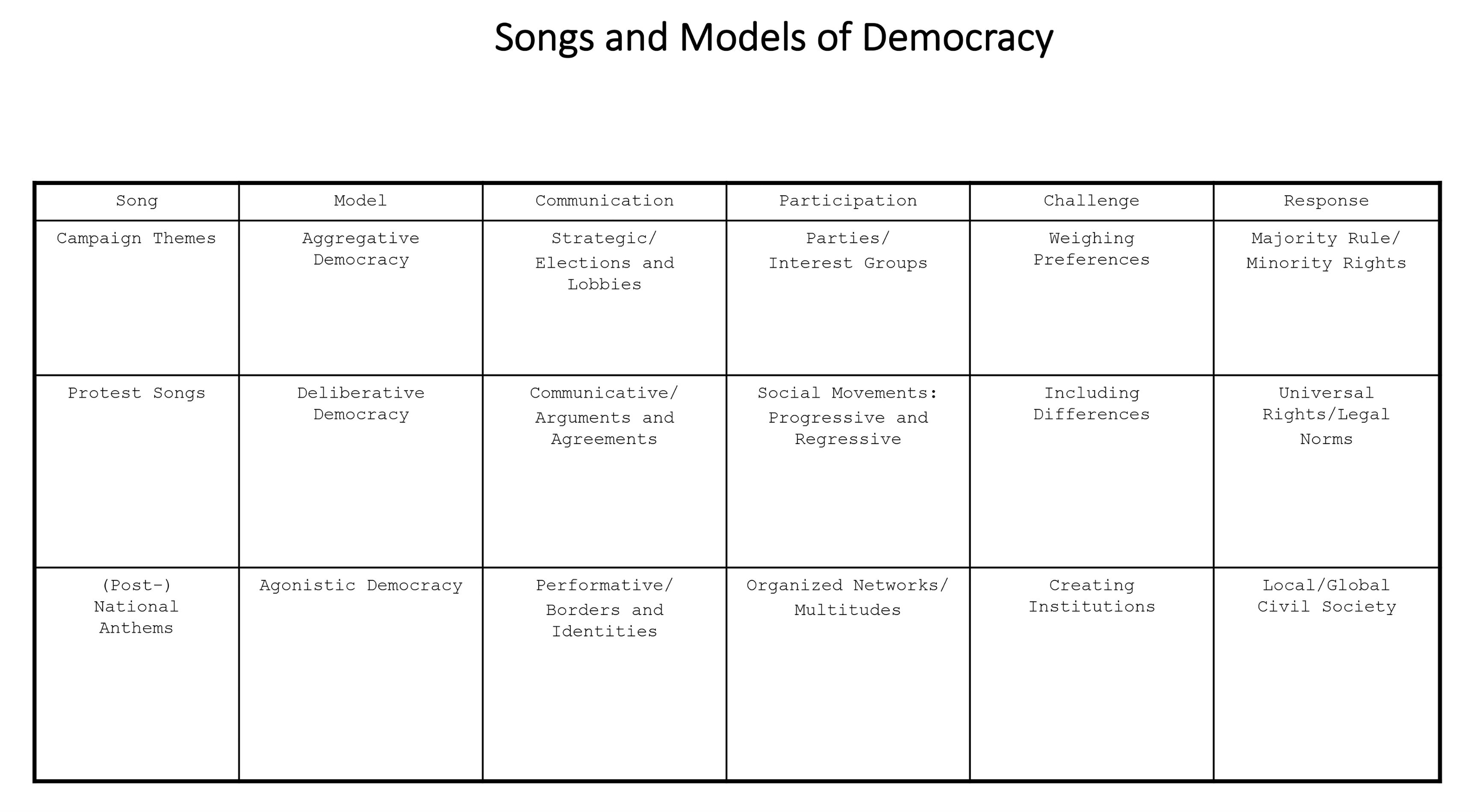

In her work, Young emphasizes three models of democracy: aggregative, deliberative, and agonistic. I have argued elsewhere that music or, more precisely, musicking performs a different role in each model.8 According to Young, those types are: aggregative (“a process of aggregating the preferences of citizens in choosing public officials and policies,” 19); deliberative (“a means of collective problem-solving which depends for its legitimacy and wisdom on the expression and criticism of the diverse opinions of all the members of the society,” 6); and agonistic (“a struggle…a [contested] process of communicative engagement of citizens with one another,” 50). This chart provides an admittedly simplified overview of each type of democracy, and the respective roles of music in politics.

Others have written eloquently about the role of music in campaigns and elections, and I have explored how protest music contributes to deliberative democracy.9 Schoening and Kasper, Don’t Stop Thinking About the Music: The Politics of Songs and Musicians in Presidential Campaigns. Here, I focus on agonistic politics, specifically the political struggles expressed by nativist/settler and native/indigenous activist musicians. In settler colonial states, white immigrants have repeatedly sought the “disappearance” of indigenous peoples through a series of practices ranging from assimilation to genocide. This history includes ongoing efforts to impose Anglo-European ideas about property, religion, and government on Native Americans/American Indians. At Standing Rock, the water protectors’ efforts to stop the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) reveal another political agon, an indigenous struggle that links music, politics, and peace. This article compares two folk songs: “Our Vinland,” by the neo-Nazi folk/pop band Prussian Blue, and “Treaty,” by the Haudenosaunee Six Nations Iroquois vocalist, Joanne Shenandoah. Their music respectively represents the current resurgence of settler colonialism and the indigenous spirit of resistance to it as witnessed at Standing Rock.

Imagined Communities in Nativist and Native Music

Folk music is most typically associated with protest songs of social justice movements – civil rights, environmental, feminist, labor, and peace.10 Eyerman and Jamison, Music and Social Movements, Mobilizing Traditions in the Twentieth Century, 52. However, folk music also expresses the cultural identity of isolated, and hence presumably authentic linguistic, racial, and/or national groups.11 Miller, Segregating Sound: Inventing Folk and Pop Music in the Age of Jim Crow. 52. In the United States, the folk music scene has historically been predominantly white, a concern for many social justice advocates.12 The social justice musician Ani DiFranco says, “It’s amazing…you go to a folk festival and there’s so many white people out in the field that it’s hard to keep track of them all. I mean, I like folk music because it tends to span generations, but it does tend to be a white thing and that’s kind of a drag. It’s kind of a drag that the world is so segregated….” [Quoted in Quirino, Ani Di Franco: Righteous Babe Revisited, 41.] An extreme version of this phenomenon is neo-Nazi folk music represented here by Prussian Blue’s white nationalist song, “Our Vinland.” “Our Vinland,” Prussian Blue, and Settler Colonialism13 For a more extensive discussion, see my Trendy Fascism: White Power Music and the Future of Democracy , ch. 3. Also see, my “Privileged Intersections: The Race, Class, and Gender Politics of Prussian Blue.”

For those unfamiliar with Prussian Blue, the band consisted of twin teenage girls – Lamb and Lynx Gaede – who first performed together in 2001 when they were nine years old at the white nationalist festival, “Eurofest,” and quickly became white nationalist folk/pop stars. Many songs on their first CD, Fragment of the Future, released in 2004, are white nationalist folk ballads written by others. Others are settings of famous poems, for example, Rudyard Kipling’s “The Stranger,” and some songs on their 2005 CD, The Path We Chose, were composed by the teens themselves. In 2006 with financial support from the National Democratic Party of Europe (NPD) the band released a compilation album, For the Fatherland. In 2007, the band toured Europe performing at white nationalist festivals. After several years, Prussian Blue disbanded and the girls began to distance themselves from their previous white supremacist views. It remains to be seen whether they will reemerge in the white power or possibly another music scene.

Prussian Blue’s neo-Nazi folk songs join, coopt, and shift the long-standing reformist tradition of white folk music in America. They embrace folk music as a racially-pure expression of white culture and use it to reinvoke an imagined – now transnational -- white community. According to Benedict Anderson, who coined the term, the nation "is imagined because the members of even the smallest nation will never know most of their fellow-members, meet them, or even hear of them, yet in the minds of each lives the image of their communion."14Anderson, Imagined Communities, 6-7. The imagined transnational community invoked by Prussian Blue is marked by a racial(ized) hierarchy. A national family, with birth requirements for naturalized citizenship, claims an American “homeland,” a protected white space in a dangerous, globalizing world. “Home” functions here as a nativist metaphor for mother country, and efforts to maintain privatized familial and racial(lized) national spaces often overlap. The underlying logic is that everything has its place, a logic that stresses the need to maintain borders and exclude “Others.”15 Collins, “It’s All in the Family: Intersections of Gender, Race, and Nation.” The Gaede’s consistently have claimed that they are white separatists, not white supremacists. According to April Gaede, the twins’ mother and manager, white supremacy only makes sense when races are already mixed and must remain so. A better option is to segregate the races either voluntarily or, if necessary, by the government, so that each has (and knows) their own place in the world.

In “Our Vinland,” Prussian Blue calls the white homeland Leif Erikson’s name for North America and a poetic Norse term for the Danish island of Sjelland, or Pasture Island. Vinland is a pastoral homeland of almost unbearable beauty: “Our hearts are filled with Love and Pride for Vinland is our home/ The hills and dales are in our souls and the forests ours to roam.”16Prussian Blue, “Our Vinland.” They compare Vinland to Valhalla, or the afterworld where their white ancestors live on to feast with the gods. Calling on the living and the dead to protect the(ir) white homeland, they ask, “Will we stand and watch them [the government] taking our freedom away?”17Ibid. Conspicuously absent in “Our Vinland” [emphasis mine] is any reference to First Nations peoples, the indigenous inhabitants of the United States. For indigenous peoples, settler colonialism has made “white separatist or white supremacist” into a distinction without a difference.

This “disappearance” of indigenous peoples typifies settler colonial narratives. Colonialism typically involves settlers who encounter local inhabitants, who they presume are lesser beings and whose lands they conquer and labor they exploit. With settler colonialism, these racialized hierarchies persist, but with different implications. According to Lorenzo Veracini, the settler colonialist constructs a narrative of “non-encounter” with the conquered that is motivated by “a recurring need to disavow the presence of indigenous others.”18 Veracini, “Introducing Settler Colonial Studies,” 2. The disappearance of native peoples often occurs over a period of many years and it takes multiple forms, such as “being physically eliminated or displaced, having one’s cultural practices erased, being ‘absorbed,’ ‘assimilated’ or ‘amalgamated’ in the wider population.” 19 Ibid. Settler colonists need indigenous inhabitants to “go away” in order to declare themselves permanently settled in their new homeland. By erasing any historical memory of the(ir) original conquest, settler colonists can legitimate their property rights and political sovereignty. For this reason, settler colonialism is typically most evident in its early phases when it is least developed. Once settler colonialism prevails, a postcolonial/postracial era can seemingly begin.

Today, Prussian Blue’s “Our Vinland” represents not only a mythic white past, but also a desired future. It is a theme song for an updated settler colonialism, the Pioneer Little Europe movement that seeks to found a global network of white ethnic communities. The Pioneer Little Europe Prospectus compares these “new” white ethnic settlements to “American Indian tribes [who] have held their own right to hold community living space for a much longer period of time.”20Barrett, The Pioneer Little Europe Prospectus. For example, April Gaede claims that “apparently only White people cannot work for the advancement of their race…. What if the 14 words said, ‘We must secure the existence of our race and a future for Native American children’ instead of ‘We must secure the existence of our race and a future for White children.’ Would human rights activists call that racist?”21Quoted in Holthouse, “High Country Extremism: Pioneering Hate.” This troubling analogy not only ignores the original European settlers’ invasion of Native American lands. It also falsely presents Indian reservations as voluntary arrangements, as separate homelands created by the US government to protect Native Americans and their cultures.22See Keeler, “On Cliven Bundy’s ‘Ancestral Rights’: If the Nevada rancher is forced to pay taxes or grazing fees, he should pay them to the Shoshone.”

With such analogies, white Anglo-European immigrants reenact the disappearance of indigenous inhabitants that typifies settler colonial nations. Descendants of the original European settlers now must fight nonwhite immigrants, who are invading “their” white(ned) American homeland. These later generation white settlers are the new victims today, the US citizens whose group rights and cultural identity are supposedly endangered. Their deepest fears of white extinction are now displaced onto an “Other,” whether original indigenous inhabitants or more recent immigrants to America. I turn now to Joanne Shenandoah’s song “Treaty,” and the struggle at Standing Rock.

“Treaty,” Joanne Shenandoah, and Standing Rock

In 2016, the Standing Rock Sioux and their supporters captured public attention and received international support in opposition to the Dakota Access Pipeline. At this writing, they and other tribes have litigated four cases, collectively known as Standing Rock I-IV, against the US Army Corps of Engineers in their attempt to stop the pipeline.23Those cases are: I. Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, et al., Plaintiffs, v. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, et al., Defendants, Civil Action # 16-1534; II. Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, Plaintiff, and Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe, Plaintiff-Intervenor, v. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Defendant, and Dakota Access, LLC, Defendant-Intervenor and Cross-Claimant, No. 16-1534 (JEB); III. Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, et al., Plaintiffs, v. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, et al., Defendants, Civil Action No. 16-1534 (JEB); IV. Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, et al., Plaintiffs, v. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, et al., Defendants, Civil Action #16-1534 (JEB). For “Field Notes” on “religion, indigeneity, and activism” at Standing Rock, see Johnson and Kraft, “Standing on the Sacred: Ceremony, Discourse, and Resistance in the Fight against the Black Snake.” International support included divestment in the pipeline by foreign banks,24” a UN resolution against the use of unreasonable force,25Tribal Chairman David Archambault II testified before the UN Human Rights Commission in Geneva about the destruction of sacred sites and the potential for pollution from the pipeline: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dWod_WsuLoY . In November 2016, the UN Special Rapporteur condemned the use of excessive force against the Sioux water protectors, and in May 2017, the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues did the same. and the Songs for Standing Rock project, which has raised over $330,000 primarily to cover legal fees.26The Songs for Standing Rock website includes the following statement: “Artists Unite, Water is Life, Activate Now.” The project description reads: “Donated by each artist, the music illustrates how art directly connects to the landscape of what is happening in society and how the artists are willing to put their songs, their voice, and their beliefs into the airwaves in support of what they believe to be right. To date, the project has issued six CDs, which are available on Amazon, ITunes, and Spotify. The latest CD was released in June 2017. https://www.songsforstandingrock.com/ The water protectors’ struggle at Standing Rock continues the long history of indigenous resistance to resource extraction and treaty violations on native lands. Often these indigenous struggles have involved native music, including the reunion of the Great Sioux Nation -- Lakota, Dakota, and Nakota – through a series of Black Hills Unity Concerts.27 On these concerts, see http://theunityconcert.wixsite.com/blackhillsnotforsa-1 President Obama (aka Barack Black Eagle), the first President to campaign on an Indian reservation and an adopted member of the Crow Nation, challenged the Sioux to reunite when he refused to negotiate over the Black Hills and DAPL with individual tribes.

Joanne Shenandoah, a member of the Haudenosaunee Wolf Clan and the Oneida-Iroquois Nation, performed at the 1980 Paha Sapa (Black Hills) Festival, which marked the US Supreme Court ruling that the Black Hills were illegally taken from the Sioux. She also performed at the 2013 gathering in Spearfish, South Dakota of the International Council of the Thirteen Indigenous Grandmothers on the anniversary of Crazy Horse’s assassination. Although I am not Native American, I participated in this Council gathering, which focused on education of, by, and for Native Americans. The Grandmother’s Council was the vision of my Seneca-Iroquois teacher, Twylah Nitsch. Given the long history of white appropriation, I do not speak or write of these matters without permission.

In contrast to Prussian Blue’s nativist “Our Vinland,” Joanne Shenandoah sings from the peace traditions of the Iroquois Confederacy which helped shape the American founding.28 Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin were among the founders who held dual citizenship in the Iroquois Confederacy and the Haudenosaunee Great Law of Peace inspired the original Articles of Confederation. See Johansen, Forgotten Founders: How the American Indian Helped Shape Democracy; Gunn Allen, The Sacred Hoop: Recovering the Feminine in American Indian Traditions. For the story of the Iroquois peacemaker, see: Shenandoah The Peacemaker’s Journey.Her song, “Treaty,” cultivates respect for the land and all our relations. Media reports of the DAPL controversy often stressed that the pipeline, which was rerouted to bypass the Missouri River north of Bismarck, North Dakota, was not on reservation land. However, as the courts recognized, the pipeline crosses native lands unceded by the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie, pipeline construction excavated native Nation historic sites, including burial grounds, and, most important, the pipeline’s path desecrates the ceremonial waters of Lake Oahe. In her song, “Treaty,” Shenandoah disparages treaties based on European settlers’ understanding of land ownership. She affirms another treaty between human beings, other living creatures, and the earth herself: “Remember the treaty you have made with me. /As long as grass grows and the sky is blue and rivers run free. /Does this not mean forever? Or did we not agree? /Will lies and broken promises be your legacy?”29Shenandoah, “Treaty.”

This latter treaty refuses ownership of the land. The Lakota invoked it when they responded to the proposed 1980 legal settlement offer by insisting that the “Black Hills are not for sale.”30 Hopkins, “Reclaiming the Sacred Black Hills,” Indian Country Today, June 28, 2014; Cook, “If They’re Not For Sale, What Are the Black Hills For?” Indian Country Today, September 4, 2016. More recently, when the veterans arrived at Standing Rock, General Wesley Clark Jr. asked forgiveness of Arvol Looking Horse, keeper of the sacred peace pipe, and declared their service to the Standing Rock Sioux. In response, Looking Horse offered a teaching on peace, world peace: “We do not own the land, the land owns us.”31 See Chief Arvol Looking Horse, et al., https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1PH7fOpgxOA

According to Julian Brave Noisecat, indigenous peoples share a relationship to the land and water “as sacred, living relatives, ancestors, places of origin or any combination of the above.”32 Noisecat, “The western idea of private property is flawed. Indigenous peoples have it right.” Shenandoah’s “Treaty” represents this relationship between politics, land, and the sacred. Although treaties with the US government can serve as imperfect affirmations of tribal sovereignty, tribal law stipulates that they cannot be made solely by a tribal majority or even by its leaders.33 For a fascinating comparison of the nation as “imagined community and this “treaty imaginary",” see Rifkin, Beyond Settler Time.

Shenandoah instead invokes a Council gathering of the buffalo, the eagle, the forest, the trees, the oceans, and the children, and she implores, “Hear me, Mr. President... This is Sacred Ground. You cannot own my Spirit, though you might lay me down. You cannot take my Spirit... This is Sacred Ground.”34 Shenandoah, “Treaty.” With these lyrics, Shenandoah reinvokes a connection to the land that was broken by European settlers, whom she accuses of “destroying creation that came before their words” – and, I would add, deeds.

Shenandoah tells the story of this destruction in “One Silver, One Gold,” another song about two serpents who were lost at sea and saved by native peoples. These silver and gold serpents were the European refugees who sailed across the Atlantic to America. After they arrived in the(ir) “new” world, “They left a trail of destruction/Cut through the mountains, rivers, and streams/They scarred the earth as they devoured/Our children and ancient dreams.”35 Shenandoah, “One Silver, One Gold.” For a discussion of these silver and gold serpents, see George-Kanentlio, “Iroquois Prophecy and the People at Standing Rock.” On restoring the earth connections of spiritually-disconnected peoples, see “Chief Arvol Looking Horse Speaks.” Also see Chief Looking Horse’s December 7, 2005 Letter to the US Department of the Interior in which he writes the following: “My work has focused on educating the International communities of the importance of protecting and preserving the remaining Sacred Sites. These Sites are viewed as the energy points or the umbilical cords to our Grandmother Earth, which usually have precious elements deposited deep below or above. These are elements now exploited causing an unbalance in all living things.” As a result, indigenous peoples and the earth herself are now in mortal danger. In “Mother Earth Speaks,” Shenandoah describes natural resource extraction as the rape and theft of Mother Earth. The song affirms the earth as a living being with a beating heart. Shenandoah’s refrain, “Don’t steal my thunder/Don’t break my heart. I’m your mother/Hear my beating heart,” again invokes prophecy: the lightning strikes of the thunder beings are meant to keep the destructive serpents underground.36Shenandoah, “Mother Earth Speaks.” Today those serpents (the black snake) have emerged in the pipeline that carries the oily remains of earlier European serpents and other decayed organisms.

After centuries of settlers extracting precious metals and now black gold, Shenandoah’s “Treaty” recreates a spiritual connection to the earth. Her music becomes a life force whose sounds flow like water and links language to the earth. “Treaty” resists the tendency of language to dichotomize, essentialize, or universalize Otherness, and to resolve differences by making the Many into One. Another indigenous musician, Joy Harjo, responds this way when asked why Native American languages have no word for music:

It's probably because [music is] so integrated into life, you know; it’s like breathing. It’s a whole different relationship. You don’t have artist/audience. You have participant. It’s more like participation, not set up [as] artist/admirers…. Everyone is a participant and it’s a whole different way to think of your place in the world as a human, and as someone who sings.37Quoted in Diamond, “Native American Contemporary Music: The Women,” 31.

Shenandoah, whose native name is She Sings,38 Shenandoah discusses her name and the role of Iroquois elders in naming children in the following interview: “An interview with Joanne Shenandoah,” Cultural Survival Quarterly (June 2000). and who began singing when she was five, similarly articulates the role of song for the Iroquois: “There are songs for when a new baby is born…and songs for when someone is passing into the spirit world. We sing for the plants, the medicines, the animals, and the harvest. There are hundreds and hundreds of songs.”39 Quoted in Harris, Heartbeat, Warble, and the Electric Powwow: American Indian Music, 88. Although Shenandoah sings some songs, including those quoted here, in English, others are sung in Iroquois dialect and with vocables. Because Shenandoah invokes a sense of creation before words for her listeners, she refuses to translate these songs, saying “Some people ask me for the translation of songs…but I tell them that they’re about a nonliteral place. I don’t want to call it a ‘trance,’ but it’s a ritual, not something that we need to define or dissect, just a way to put ourselves into a circle of well-being.”40Quoted in Ibid., 89.

Hearing the Music and Becoming a Peace Warrior

The Songs for Standing Rock website claims that the many musicians, who performed for Standing Rock, helped create a “forcefield of sound” to protect the water protectors, the water, and the earth.41https://www.songsforstandingrock.com/ Yet some who joined the Standing Rock Sioux at the Oceti Sakowin camp did not respect native traditions and, given their lack of understanding, became a burden on the tribes. In November 2016, Alicia Smith sounded an alarm, stating that, “White people are colonizing the camps. I mean that seriously. Plymouth rock seriously.”42Quoted in O’Connor, “Standing Rock: North Dakota access pipeline demonstrators say white people are ‘treating protest like Burning Man’” Others noted that “complaints grow over whites turning Dakota Access protest into hippie festival,” like Burning Man or the Rainbow Tribe Festival.43Richardson, “Complaints grow over whites running Dakota Access protest into hippie festival.” Mr. Archambault II, Former Tribal Chairman of the Standing Rock Sioux, compared human contamination of the flood plain where Oceti Sakowin was located to the pollution from the pipeline itself. In spite of tribal resistance to the Army Corps of Engineer’s eviction order, he called for the main camp to be closed. Eventually, those who stayed were evicted and their shelters burned, according to native traditions. At this writing, the pipeline is operational, oil spills have already occurred, and the struggle continues in the courts and at the UN.

Within the folk genre, the contrast between Prussian Blue’s “Our Vinland” and Shenandoah’s “Treaty” is striking.44It is important to recognize that native music today, including Shenandoah’s, is not traditional in any simple way. Indigenous music reflects the influences of multiple cultures and involves far more that “chants, drums, and flutes.” For a discussion of tensions between traditional and modern in Native American music, see Ullestad, “American Indian Rap and Reggae: Dancing ‘To the Beat of a Different Drummer.’” Prussian Blue promotes fear of an “Other” and white fight or flight with its repeated question, “Will we stand and watch them taking our freedom away?” Shenandoah instead invokes a sense of balance within individuals, and between cultures and species. Regarding the “micro-politics of peace,” music therapists have found that Shenandoah’s music promotes not “fight or flight” responses, but an alternative they call the “relaxation response.”45 Xueli et. al., “The Interplay of Preference, Familiarity and Psychophysical Properties in Defining Relaxation Music.” Music that prompts the relaxation response has “sustained melodic lines, non-percussive, quiet, and even and simple rhythms with lots of repetition” (152). On the macro-level, by unsettling the categories and values of the white West, “Treaty” expresses a shared (human) identity and a sense of (earthly) place. In so doing, it promotes a non-violent approach to cultural and linguistic differences consistent with the Haudenosaunee Great Law of Peace.46When Shenandoah was asked to open Woodstock ’94, she chose the song, “America.” As she describes it, “We opened with a song that I wrote, ‘America,’ about the tree of peace, the four directions, and people of all colors coming together.” [Quoted in Harris, 89.]

One of Shenandoah’s first songs, “They Didn’t Listen,” expresses the harsh reality for indigenous peoples today of living simultaneously in two profoundly different worlds: native and settler. The song presents the cycle of destruction unleashed by white men: they first dig for gold; next the eagle dies, leaving no keeper of the land; then machines pollute the sky and the sea. The final verse circles back: “I told them of the day foretold, for if they did the eagle would die,” and the chorus repeats “They didn’t listen/They didn’t listen to me.”47Shenandoah, “They Didn’t Listen.”

Of course, ethnomusicologists have long listened to native music, recording and transcribing it for posterity. In Modernity’s Ear: Listening to Race and Gender in World Music, Roshanak Kheshti argues that “the aural imaginary” of white listeners has thrived on the assimilation, appropriation, and most important, incorporation of indigenous music. Female “song catchers,” she argues, often performed the “talking machine ‘cure,’” bringing indigenous Others into modern civilization with recording devices that served as phallus substitutes.48Perhaps the most famous example is the ethnomusicologist, Frances Densmore, the author of Teton Sioux Music and Culture. Kheshti discusses Densmore’s work and the film, “The Song Catcher,” about the fictitious Lily Penleric, a prototypical female musicologist, in Appalachia. [Khesti, Modernity’s Ear: Listening to Race and Gender in World Music] Like Jonathan Sterne, Kheshti associates the use of modern recording technology with the feminization of listening; the conical orifice of the human ear, like the early Victrola, performs the incorporation of sound.49Sterne, The Audible Past: Cultural Origins of Sound Reproduction.

It is not enough, then, for the descendants of white settlers merely to listen to indigenous music. Although listening may increase cultural understanding, more is required of the white listener – male or female – who would actually hear the music. What would it mean for Shenandoah’s “Treaty” and her other songs to be heard by the descendants of white settlers who reside in America today? Kheshti discusses several examples of what she calls “radical listening,” an alternative to the incorporation of indigenous music by modernity’s ear. Most relevant here is her discussion of the methodology of refusal that Audre Simpson articulates in Mohawk Interruptus: Political Life across the Borders of Settler States.50 Simpson, Mohawk Interruptus: Political Life Across the Borders of Settler States. For Simpson, the refusal of ethnographers and their subjects to “tell all” asserts that “sovereignty matters”; it expresses “a calculus ethnography of what you need to know and what I refuse to write in.”51 Quoted in Khesti, 131. By refusing to expose her indigenous subjects and herself to the disciplinary (in its many senses) norms of cultural anthropology, Simpson challenges the “ethnographic gaze” -- I would add, “ear” – and the dominant power/knowledge regime.

What, though might radical listening mean for the descendants of white settlers who reside in America today? In closing, I would apply Simpson’s methodological insights to several of my experiences at the gathering of the International Council of the Thirteen Indigenous Grandmothers. The first is an interruption of the dominant narrative: during one native prayer ceremony, many white participants began softly to hum and sing “Amazing Grace” together. The second, a refusal to presume access: after the pipe ceremony, I had a chance to speak with Arvol Looking Horse, and said only “I am here to honor you.” The third, a heartfelt prayer: driving across South Dakota to the Council gathering, I prayed at the gravesite of my ancestor who fought in the Civil War and the Indian Wars that our family would someday become the ancestors of warriors for peace. The fourth, an intergenerational promise: a young native woman closed the Council gathering by teaching participants the Lakota woman warrior song, which we then sang together.

Did I hear the music at the Council gathering I attended? I like to think so, at least some of it. What I know is that I no longer merely apologize for white nativism and white supremacy, but instead expose it and act with indigenous peoples. In Responsibility for Justice, Iris Young distinguishes between assigning blame and taking responsibility. Unlike blame, which is backward looking, responsibility is forward looking and brings change. She writes: “Those who are beneficiaries of racialized structures with unjust outcomes…can properly be called to a special moral and political responsibility to recognize our privilege, to acknowledge its continuities with historical injustice, and to act on an obligation to work on transforming the institutions that offer this privilege, even if this means worsening one’s own conditions and opportunities compared to what they would have been.“52 Young, Responsibility for Justice, 187. For me, hearing native voices has meant accepting the responsibility to change the cognitive frameworks, embodied experiences, and institutional structures of white power and privilege. There are many ways to do this work, including remembering the songs and stories of the indigenous peoples who foretold of these times on earth.

Doug George Kanentiio, an Akwesasne Mohawk, and Joanne Shenandoah’s husband, explicitly links Iroquois prophecy to Standing Rock, saying “His [the Peacemaker’s] instruction was clear: to use whatever means available to teach the principles of the Great Law of Peace and thereby bring an end of warfare among all nations and to show the world that harmony between the natural world and human beings was possible.”53 Kanetiio, “Iroquois Prophecy and the People at Standing Rock.” The Haudenosaunee flag flew at the #noDAPL protests in Washington, DC to carry this message to the people at Standing Rock: “There is hope, there is light as long as they hold onto the principles of peace and unity. The ancestors will respond in ways unforeseen and remarkable.”54Ibid. I close with these words from the Haudenosaunee Great Law of Peace:

I, Deganawida, and the United Chiefs, now uproot the tallest tree and into the hole thereby made, we cast all weapons of war. Into the depths of the earth, down into the deep underneath currents of water flowing to unknown regions we cast all the weapons of strife. We bury them from sight and we plant again the tree. Thus, shall the Great Peace be established and hostilities shall no longer be known between the Five Nations, but peace to the United People.55For the complete text, see http://www.ganienkeh.net/thelaw.html

Notes

1 Love, “Politics and Music.”

2 Quoted in Laurence, “Music and Empathy,” 14.

3 Quoted in Ibid.

4 On Habermas’s musical metaphors, see Love, Musical Democracy, ch. 2.

5 Young, Democracy and Inclusion, 53-57.

6 Habermas, The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere.

7 Young, Democracy and Inclusion, 13.

8 According to Young, those types are: aggregative (“a process of aggregating the preferences of citizens in choosing public officials and policies,” 19); deliberative (“a means of collective problem-solving which depends for its legitimacy and wisdom on the expression and criticism of the diverse opinions of all the members of the society,” 6); and agonistic (“a struggle…a [contested] process of communicative engagement of citizens with one another,” 50).

9 Schoening and Kasper, Don’t Stop Thinking About the Music: The Politics of Songs and Musicians in Presidential Campaigns.

10 Eyerman and Jamison, Music and Social Movements, Mobilizing Traditions in the Twentieth Century, 52.

11 Miller, Segregating Sound: Inventing Folk and Pop Music in the Age of Jim Crow.

12 The social justice musician Ani DiFranco says, “It’s amazing…you go to a folk festival and there’s so many white people out in the field that it’s hard to keep track of them all. I mean, I like folk music because it tends to span generations, but it does tend to be a white thing and that’s kind of a drag. It’s kind of a drag that the world is so segregated….” [Quoted in Quirino, Ani Di Franco: Righteous Babe Revisited, 41.]

13 For a more extensive discussion, see my Trendy Fascism: White Power Music and the Future of Democracy, ch. 3. Also see, my “Privileged Intersections: The Race, Class, and Gender Politics of Prussian Blue.”

14 Anderson, Imagined Communities, 6-7.

15 Collins, “It’s All in the Family: Intersections of Gender, Race, and Nation.”

16 Prussian Blue, “Our Vinland.”

17 Ibid.

18 Veracini, “Introducing Settler Colonial Studies,” 2.

19 Ibid.

20 Barrett, The Pioneer Little Europe Prospectus.

21 Quoted in Holthouse, “High Country Extremism: Pioneering Hate.”

22 See Keeler, “On Cliven Bundy’s ‘Ancestral Rights’: If the Nevada rancher is forced to pay taxes or grazing fees, he should pay them to the Shoshone.”

23 Those cases are: I. Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, et al., Plaintiffs, v. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, et al., Defendants, Civil Action # 16-1534; II. Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, Plaintiff, and Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe, Plaintiff-Intervenor, v. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Defendant, and Dakota Access, LLC, Defendant-Intervenor and Cross-Claimant, No. 16-1534 (JEB); III. Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, et al., Plaintiffs, v. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, et al., Defendants, Civil Action No. 16-1534 (JEB); IV. Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, et al., Plaintiffs, v. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, et al., Defendants, Civil Action #16-1534 (JEB). For “Field Notes” on “religion, indigeneity, and activism” at Standing Rock, see Johnson and Kraft, “Standing on the Sacred: Ceremony, Discourse, and Resistance in the Fight against the Black Snake.”

24 Energy Transfer Partners includes four subsidiaries (Energy Transfer Equity, Sunoco, PennTex, and Phillips 66). See http://www.energytransfer.com/company_overview.aspx. Thirty-five banks supported the companies building the pipeline with $10.25 billion in loans and credit. They include: Bank of Nova Scotia, Citizen’s Bank, Comerica Bank, US Bank, PNC Bank, Barclays, JP Morgan Chase, Bank of America, Deutsche Bank, Credit Suisse, Royal Bank of Canada, UBS, Goldman-Sachs, and Morgan Stanley. The Norwegian pension fund KLP divested over $68 million in the pipeline due to pressure from the Sami peoples of Norway, among others. Seattle, Washington and Davis, California have also divested from Wells Fargo due to its support for DAPL. On divestment, see: http://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2017/03/17/520545209/norwegian-pension-fund-divests-from-companies-behind-dapl .

25 Tribal Chairman David Archambault II testified before the UN Human Rights Commission in Geneva about the destruction of sacred sites and the potential for pollution from the pipeline: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dWod_WsuLoY. In November 2016, the UN Special Rapporteur condemned the use of excessive force against the Sioux water protectors, and in May 2017, the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues did the same.

26 The Songs for Standing Rock website includes the following statement: “Artists Unite, Water is Life, Activate Now.” The project description reads: “Donated by each artist, the music illustrates how art directly connects to the landscape of what is happening in society and how the artists are willing to put their songs, their voice, and their beliefs into the airwaves in support of what they believe to be right. To date, the project has issued six CDs, which are available on Amazon, ITunes, and Spotify. The latest CD was released in June 2017. https://www.songsforstandingrock.com/

27 On these concerts, see http://theunityconcert.wixsite.com/blackhillsnotforsa-1

28 Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin were among the founders who held dual citizenship in the Iroquois Confederacy and the Haudenosaunee Great Law of Peace inspired the original Articles of Confederation. See Johansen, Forgotten Founders: How the American Indian Helped Shape Democracy; Gunn Allen, The Sacred Hoop: Recovering the Feminine in American Indian Traditions. For the story of the Iroquois peacemaker, see: Shenandoah The Peacemaker’s Journey.

29 Shenandoah, “Treaty.”

30 Hopkins, “Reclaiming the Sacred Black Hills,” Indian Country Today, June 28, 2014; Cook, “If They’re Not For Sale, What Are the Black Hills For?” Indian Country Today, September 4, 2016.

31 See Chief Arvol Looking Horse, et al., https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1PH7fOpgxOA

32 Noisecat, “The western idea of private property is flawed. Indigenous peoples have it right.”

33 For a fascinating comparison of the nation as “imagined community and this “treaty imaginary,” see Rifkin, Beyond Settler Time.

34 Shenandoah, “Treaty.”

35 Shenandoah, “One Silver, One Gold.” For a discussion of these silver and gold serpents, see George-Kanentlio, “Iroquois Prophecy and the People at Standing Rock.” On restoring the earth connections of spiritually-disconnected peoples, see “Chief Arvol Looking Horse Speaks.” Also see Chief Looking Horse’s December 7, 2005 Letter to the US Department of the Interior in which he writes the following: “My work has focused on educating the International communities of the importance of protecting and preserving the remaining Sacred Sites. These Sites are viewed as the energy points or the umbilical cords to our Grandmother Earth, which usually have precious elements deposited deep below or above. These are elements now exploited causing an unbalance in all living things.”

36 Shenandoah, “Mother Earth Speaks.”

37 Quoted in Diamond, “Native American Contemporary Music: The Women,” 31.

38 Shenandoah discusses her name and the role of Iroquois elders in naming children in the following interview: “An interview with Joanne Shenandoah,” Cultural Survival Quarterly (June

2000).

39 Quoted in Harris, Heartbeat, Warble, and the Electric Powwow: American Indian Music, 88.

40 Quoted in Ibid., 89.

41 https://www.songsforstandingrock.com/

42 Quoted in O’Connor, “Standing Rock: North Dakota access pipeline demonstrators say white people are ‘treating protest like Burning Man’”

43 Richardson, “Complaints grow over whites running Dakota Access protest into hippie festival.”

44 It is important to recognize that native music today, including Shenandoah’s, is not traditional in any simple way. Indigenous music reflects the influences of multiple cultures and involves far more that “chants, drums, and flutes.” For a discussion of tensions between traditional and modern in Native American music, see Ullestad, “American Indian Rap and Reggae: Dancing ‘To the Beat of a Different Drummer.’”

45 Xueli et. al., “The Interplay of Preference, Familiarity and Psychophysical Properties in Defining Relaxation Music.” Music that prompts the relaxation response has “sustained melodic lines, non-percussive, quiet, and even and simple rhythms with lots of repetition” (152).

46 When Shenandoah was asked to open Woodstock ’94, she chose the song, “America.” As she describes it, “We opened with a song that I wrote, ‘America,’ about the tree of peace, the four directions, and people of all colors coming together.” [Quoted in Harris, 89.]

47 Shenandoah, “They Didn’t Listen.”

48 Perhaps the most famous example is the ethnomusicologist, Frances Densmore, the author of Teton Sioux Music and Culture. Kheshti discusses Densmore’s work and the film, “The Song Catcher,” about the fictitious Lily Penleric, a prototypical female musicologist, in Appalachia. [Khesti, Modernity’s Ear: Listening to Race and Gender in World Music]

49 Sterne, The Audible Past: Cultural Origins of Sound Reproduction.

50 Simpson, Mohawk Interruptus: Political Life Across the Borders of Settler States.

51 Quoted in Khesti, 131.

52 Young, Responsibility for Justice, 187.

53 Kanetiio, “Iroquois Prophecy and the People at Standing Rock.”

54 Ibid.

55 For the complete text, see http://www.ganienkeh.net/thelaw.html

Bibliography

Anderson, Benedict. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. New York, NY: Verso, 2016.

Archambault II, David. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dWod_WsuLoY

Barrett, Michael H. Pioneer Little Europe Prospectus. https://archive.org/details/pleprospectus

Black Hills Unity Concerts. http://theunityconcert.wixsite.com/blackhillsnotforsa-1

Chappell, Bill. “2 Cities to Pull More Than 3 Billion from Wells Fargo Over Dakota Access Pipeline.” The Two Way: Breaking News from NPR, February 8, 2017. http://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2017/02/08/514133514/two-cities-vote-to-pull-more-htan-3-billion-from-wells-fargo-over-dakota-pipelin

Collins, Patricia Hill. “It’s All in the Family: Intersections of Gender, Race, and Nation.” Hypatia: Journal of Feminist Philosophy 13, no. 3 (1998): 62-82. doi:10.2979/hyp.1998.13.3.62.

Cook, Tom. “If They’re Not For Sale, What Are the Black Hills For?” Indian Country Today, September 4, 2016.

Densmore, Frances. Teton Sioux Music and Culture. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1981.

Diamond, Beverley. “Native American Contemporary Music: The Women.” In The World of Music, Indigenous Popular Music in North America: Continuations and Innovations 44:1 (2002): 11-39.

Domonoske, Camilia. “Norwegian Pension Fund Divests from Companies Behind DAPL.” The Two Way: Breaking News From NPR, March 17, 2017. http://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2017/03/17/520545209/norwegian-pension-fund-divests-from-companies-behind-dapl

Eyerman, Ron and Andrew Jamison. Music and Social Movements, Mobilizing Traditions in the Twentieth Century. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Great Law of Peace. http://www.ganienkeh.net/thelaw.html

Gunn Allen, Paula. The Sacred Hoop: Recovering the Feminine in American Indian Traditions. Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 1992.

Johnson, Greg and Siv Ellen Kraft, “Standing on the Sacred: Ceremony, Discourse, and Resistance in the Fight against the Black Snake.” Journal for the Study of Religion, Nature, and Culture, 11.1 (2017): 131-147. doi:10.1558/jsrnc.32617.

Habermas, Jürgen. The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society. Translated by Thomas Burger with the assistance of Frederick Lawrence. Boston, MA: The MIT Press, 1991.

Harris, Craig. Heartbeat, Warble, and the Electric Powwow: American Indian Music. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2016.

Holthouse, David. “High Country Extremism: Pioneering Hate.” Part 2, November 16, 2011. https://www.mediamatters.org/blog/2011/11/15/high-country-extremism-pioneering-hate/154613 .

Hopkins, Ruth. “Reclaiming the Sacred Black Hills” Indian Country Today, June 28, 2014.

Johansen, Bruce. Forgotten Founders: How the American Indian Helped Shape Democracy. Boston, MA: Harvard Common Press, 1982.

Kanetiio, Doug George. “Iroquois Prophecy and the People at Standing Rock,” indianz.com, September 15, 2016. http://www.indianz.com/News/2016/09/15/doug-georgekanentiio-prophecy-and-the-pe.asp

Keeler, Jacqueline. “On Cliven Bundy’s ‘Ancestral Rights’: If the Nevada Rancher is Forced to Pay Taxes or Grazing Fees, He Should Pay them to the Shoshone,” The Nation, April 29, 2014, http://www.thenation.com/article/179561/cliven-bundys-ancestral-rights

Khesti, Roshanak. Modernity’s Ear: Listening to Race and Gender in World Music. New York, NY: New York University Press, 2015.

Laurence, Felicity. “Music and Empathy." In Music and Conflict Transformation: Harmonies and Dissonances in GeoPolitics, edited by Olivier Urbain, 13-25. London, UK: I.B. Tauris, 2015.

Looking Horse, Arvol Chief, Letter to the US Department of the Interior, December 5, 2015.

_____. “Chief Arvol Looking Horse Speaks,” Manataka American Indian Council, May 20, 2015. http://www.manataka.org/page_2834.html.

Love, Nancy S. Trendy Fascism: White Power Music and the Future of Democracy. Albany, NY: SUNY Press, 2016.

_____. “Politics and Music.” In Encyclopedia of Political Thought, edited by Michael Gibbons, et al., London, UK: Wiley-Blackwell, 2014.

_____. “Privileged Intersections: The Race, Class, and Gender Politics of Prussian Blue,” Music and Politics, no. 1 (Winter 2012), n.p., http://quod.lib.umich.edu/m/mp/ doi:10.3998/mp.9460447.0006.102.

_____. Musical Democracy. Albany, NY: SUNY Press, 2006.

Miller, Karl Hagstrom. Segregating Sound: Inventing Folk and Pop Music in the Age of Jim Crow. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010.

Noisecat, Julian Brave. “The Western Idea of Private Property is Flawed. Indigenous peoples Have it Right,” The Guardian, March 27, 2017.

O’Connor, Roisin. “Standing Rock: North Dakota Access Pipeline Demonstrators Say White People are ‘Treating Protest like Burning Man.’” Independent, Monday, November 28, 2016.

Quirino, Raffaele. Ani Di Franco: Righteous Babe Revisited. Kingston, Ontario: Fox Music Books, 2004.

Richardson, Valerie. “Complaints Grow Over Whites Running Dakota Access Protest into Hippie Festival,” Washington Times, Monday, November 28, 1016.

Rifkin, Mark. Beyond Settler Time: Temporal Sovereignty and Indigenous Self-Determination. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017.

Schoening, Benjamin S. and Eric T. Kasper. Don’t Stop Thinking About the Music: The Politics of Songs and Musicians in Presidential Campaigns. New York, NY: Lexington, 2011.

Shenandoah, Joanne. “An Interview with Joanne Shenandoah,” Cultural Survival Quarterly (June 2000): n.p.

Simpson, Audre. Mohawk Interruptus: Political Life Across the Borders of Settler States. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2014.

Songs for Standing Rock Project. https://www.songsforstandingrock.com/

Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, et al., Plaintiffs, v. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, et al., Defendants, Civil Action # 16-1534, June 14, 2017.

_____. Civil Action No. 16-1534 (JEB), April 7, 2017

_____. Civil Action #16-1534 (JEB), September 9, 2016

Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, Plaintiff, and Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe, Plaintiff-Intervenor, v. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Defendant, and Dakota Access, LLC, Defendant-Intervenor and Cross-Claimant, Civil Action No. 16-1534 (JEB), March 7, 2017.

Sterne, Jonathan. The Audible Past: Cultural Origins of Sound Reproduction. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2003.

Ullestad, Neal. “American Indian Rap and Reggae: Dancing ’To the Beat of a Different Drummer.’” Popular Music and Society 23:2 (Summer 1999): 63-90. doi:10.1080/03007769908591733.

Veracini, Lorenzo. “Introducing Settler Colonial Studies.” Settler Colonial Studies, 1:1 (Feb. 2013): 1-12.

Xueli, Tan, and Charles J. Yowler, Dennis M. Super, Richard B. Fratianne. “The Interplay of Preference, Familiarity and Psychophysical Properties in Defining Relaxation Music.” Journal of Music Therapy 49:2 (2012): 150-179. doi:10.1093/jmt/49.2.150.

Young, Iris. Responsibility for Justice. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2013.

_____. Democracy and Inclusion. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2000.

Discography

Prussian Blue. “Our Vinland,” Fragment of the Future, CD, Resistance Records, 2004.

Joanne Shenandoah. The Peacemaker’s Journey, Silver Wave, 2000, Audio CD, ASIN: B00004R8PY.

Shenandoah, Joanne. “Treaty.” On Eagle Cries, 2016.

__________. “One Silver, One Gold.” On Eagle Cries, 2016

__________. “America.” On Once in a Red Moon, 2016.

__________. “Mother Earth Speaks.” On Once in a Red Moon, 2016.

__________. “They Didn’t Listen.” On Joanne Shenandoah, 1989.