Abstract

The poem “Songs to the Dark Virgin,” composed by Langston Hughes and included in his 1926 volume The Weary Blues, presents an obscure and complex text that seems to address an ambiguous second-person entity, the “Dark Virgin.” In this article I provide a detailed critical and theoretical analysis of Florence Price’s musical setting of the poem. I explore the literary themes of racial self-hatred, concealment, and destruction that seem to be expressed in the poetic text and compare these topics to the musical structures found within Price’s composition. Patterns of hidden motivic repetition, especially through the processes of translational parallelism and prolongational parallelism, are identified in voice-leading analyses of the song and are compared to the type of expressive metaphors described by Henry Louis Gates as “signifyin(g).” These complex multi-linear continuities are also compared to the polyvalent voice-leading interpretations described by Marianne Kielian-Gilbert as theoretical (in)determinacy. I conclude that the pattern of concealment that is so ubiquitously present in the voice-leading structure of the song also corresponds to an established trope of concealment found in many early twentieth-century African American literary and musical works.

James A. Grymes

Although recent years have seen a significant revival of interest in the music of Florence Beatrice Price (1887-1953), not as much scholarly attention has been paid to the systematic or detailed analysis of her music.1The most important biographical study of Florence Price is Ray Linda Brown’s (2020) The Heart of a Woman: The Life and Music of Florence B. Price. Within approximately the past fifteen years, a number of theses and dissertations have appeared on the subject of Price and her music, including those of Scott Farrah (2007), Bethany Smith (2007), Sarah Peebles (2008), Shana Mashego (2010), Amy Broadbent (2016), Erin Hobbs (2017), Marquese Carter (2018), Meng-Chieh Hsieh (2019), Daniel Hunter (2019), Christine Jobson (2019), Samantha Ege (2020), and Elizabeth Durrant (2021). There are also some research projects that considerably predate the recent revival of interest in Price. These sources include the monograph by Mildred Green (1983) and the thesis of Carren Moham (1997) In this article I will work toward creating a meaningful body of analytical studies on the musical works of Florence Price by providing a voice-leading examination of one of the composer’s most intriguing and perhaps most expressive compositions for solo voice, “Songs to the Dark Virgin,” the setting of a poem by Langston Hughes. I begin with a structural study of the work and then suggest that various aspects of both translational and prolongational repetition create a representation of hidden motivic parallelism, similar to the possible layers of hidden meaning in Hughes original poetic text.

Songs to the Dark Virgin

The year in which Price composed “Songs to the Dark Virgin” has not been determined.2 The earliest known manuscript for the song is dated April 26, 1935. See the description of this manuscript source provided by John Michael Cooper in his introduction to the Schirmer critical edition (Price 2021, iii). It was performed regularly by Marian Anderson, beginning approximately in 1940 (Smith 2007, 95), and published by Schirmer in 1941 (Price 1941) (Smith 2007, 111–14). The song was dedicated to the composer’s daughter, Florence L. Price.3“Songs to a Dark Virgin” has been published in numerous anthologies and the complete musical text may be easily found through an internet search. The original 1941 publication by Schirmer is reproduced in the thesis of Bethany Smith (2007, 111–14). A critical edition, edited by John Michael Cooper, has recently been issued by Schirmer (Price 2021).

Hughes’s poem “Songs to the Dark Virgin” (2020 [1926], 45) appeared in his 1926 volume The Weary Blues. The poem is comprised of three stanzas, each concluding with the refrain “Thou dark one.” The poem has been interpreted as a juxtaposition of “beautiful images against the ugly reality of life for a black American in the south” (Smith 2007, 89).4Similar to Price’s musical text, Hughes’s poem “Songs to the Dark Virgin” appears in many anthologies, including The Collected Poems of Langston Hughes (Hughes 1994, 61–62), and may be easily found through an internet search. The poem is reproduced in the thesis of Bethany Smith (2007, 67–68).

Some writers, primarily musicologists who are analyzing the meaning of Price’s art song, rather than Hughes’s original poem, have interpreted the text to represent a non-ironic idealized romantic expression. Elizabeth Durrant (2021, 21) suggested a “Black feminist analysis of Price’s song, describing the protagonist as a Black woman who is addressing her lover.” In this reading, the word “annihilate” could even be a “representation of sexual pleasure . . . Although the description of destroying the virgin’s body through flame also signifies the history of violence against Black bodies” (Durrant 2021, 25). John Michael Cooper, in his introduction to the Schirmer critical edition (Price 2021, ii), briefly describes the meaning of Price’s song as “physical, romantic, and deliciously sensual love for a beloved whose beauty—in stark contrast to the racist, dehumanizing, White-centric attitudes toward beauty in much of Hughes’s and Price’s own worlds—resides precisely in Blackness.”

The ability of the poem to be interpreted in multiple ways is perhaps the central element of Hughes’s genius in this work. As Carl Van Vechten observed in his introduction to the original edition of The Weary Blues (Hughes 2020 [1926], xxv), Hughes’s poems are the “expression of an essentially sensitive and subtly illusive nature.” This potential for polyvalent interpretation is an essential aspect of the poetry that Price extended upon and complemented through her setting of the text, the ambiguous meaning of the poem being reflected in the complexity of the musical structure.

Henry Louis Gates (1988, 49–96) has suggested an approach to the critical analysis of literature from the “Harlem Renaissance,”5The “Harlem Renaissance,” also known as the “Negro Renaissance” or the “New Negro Movement,” was a revival of African American culture, especially intellectual and artistic expression, that took place primarily in New York City and other areas of the northern and midwestern United States during the 1920s and 1930s. Hughes was one of the central literary figures of the “Harlem Renaissance.” as well as African American works of art in general, for which he uses the term “signifyin(g).”6In his dissertation, which focuses on the semiotic analysis of symphonic music by African American composers, Scott Farrah (2007, 18–19) paraphrases the definition of “signifyin(g)” suggested by Samuel A Floyd (1995, 96) as “it is a way of saying one thing and meaning something else using Afro-American stylistic tropes.” This method of criticism focuses on elements that suggest racial consciousness in the works of African American poets and authors by referencing symbolic ideas in previous texts or commonly understood euphemisms. In particular, certain established literary tropes or metaphors, which may in some cases be obscure to white readers, are intended to represent the hardships routinely experienced by African Americans. In the poem “Songs to the Dark Virgin,” the most apparent of these “signifyin(g)” elements would include the frequent references to “darkness” (“dark virgin” and “thou dark one”), brokenness (“shattered jewel”), hiding/concealment (“hide thy body”), and violence (“one sharp leaping flame” and “annihilate thy body”).

In Price’s musical setting of the poem, the brightness of the jewels in the first stanza contrasts against the darkness of the body as the opening arpeggios rise from their initial low or “dark” register. In the second stanza the piano accompaniment encircles the vocal line, similar to the “folds” of the “silken garment” that “wrap around thy body” in the poem. In the final stanza the vocal line reaches its apex on the lines “But one sharp leaping flame / To annihilate thy body.”7See the discussion of symbolic musical references in this song provided by Green (1983, 35–36), Smith (2007, 89–95), and Brown (2020, 225–26). Clearly there are easily identifiable elements of text painting in Price’s very effective setting of the poem, but deeper and more structurally significant meaning, perhaps implicating a more penetrating layer of “signifyin(g),” may also be found in the song setting as well.

Prolongational and Translational Parallelism

Marianne Kielian-Gilbert (2003, 68–75) has suggested a distinction between translational parallelism, in which a specific voice-leading configuration may be repeated at a temporal location other than the original time-placement of the event,8“To translate is to ‘transfer’ or ‘transport’ a body or form of energy from one point of space to another without rotation (or from one person, place or condition to another)” (Kielian-Gilbert 2003, 69). and prolongational parallelism, in which a voice-leading configuration may be recognized at a different structural level than its original presentation.9 In some musical works the structural voice leading of an opening motivic gesture may resemble the large-scale voice-leading reduction of an entire movement or an entire formal section. Charles Burkhart (1978) provides an explanation of this process, described by the term multi-level motivic repetition. A very similar pattern of prolongational parallelism between small and large scale tonal progressions is the subject of Irene Montefiore Levenson’s (1981) dissertation, “Motivic-Harmonic Transference in the Late Works of Schubert: Chromaticism in Large and Small Spans.” The processes of both translational parallelism and prolongational parallelism require the subjective perception of either retention (the projection of conceptually past or previous elements into the present consciousness) or protention (a projection of future expectation into the present consciousness).10Retention and protention are important aspects of Edmund Husserl’s (1964 [1928]) phenomenology of temporality. See the discussion of Husserl in David Lewin’s (2006 [1986], 53–67) article “Music Theory, Phenomenology, and Modes of Perception.” The perceptual recognition of multi-level motivic repetition means that certain elements of the structural foreground may be interpreted differently by the subjective listener depending upon the level of voice-leading that is the focus of the listener’s analytical selection. The possibility that multiple conflicting analyses of a musical work may exist at the same time has been described by Kielian-Gilbert (2003, 55–57) as theoretical-experiential (in)determinacy.

Although previous discussions of “Songs to the Dark Virgin” have described various characteristic elements of the work’s text painting and literary references, I believe that the most significant aspect of meaning in the song may be found in the overt and disturbing irony between the seemingly triumphant tonal coherence of the musical text and the destructive imagery of the poetic text. As the tonic key of C major11Although the original Schirmer edition of “Songs to the Dark Virgin” (Price 1941) is in the key of A-flat major, the Schirmer critical edition (Price 2021), edited by John Michael Cooper and based on a manuscript completed in 1935, is in the key of C major. The two versions are exact transpositions of each other, with the exception of a few orthographic elements in the piano part, such as beaming, and the absence of the optional higher notes in the voice part at the end of the song in the C major version (which are included in the 1941 version). The analytical discussion and examples in this article will follow the new critical edition, edited by John Michael Cooper, except when specifically referencing aspects of the original 1941 published version. slowly emerges from the opening A minor seventh sonority, it is confirmed by the dominant ninth chord in m. 3 and finally established by the cadence on C at the conclusion of the first stanza in m. 6. This obscured initial tonality may represent an element of Gates’s (1988) notion of “signifyin(g)” that I will describe in my analysis of “Songs to the dark Virgin” as concealment.12 I use the term concealment to suggest the process of “saying one thing and meaning another,” especially through the use of established African American tropes, or perhaps also through established tropes about “Blackness.”

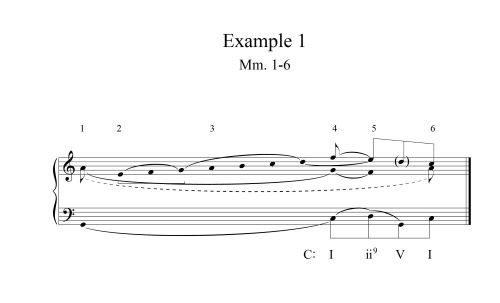

Translational parallelism may be found within the voice-leading structure of the first stanza as the prominent upper neighbor-tone appoggiatura (F resolving down to E) in m. 4 of the vocal line is repeated by the dissonant upper neighbor tone G resolving down to F in the piano (and also, rhythmically altered, in the vocal line) in m. 5. This neighbor-tone motive is then presented in its most intense form through the dissonant E in the vocal line on the word “feet” in m. 5, where it may function as the ninth of a supertonic sonority built over the D in the bass. Retrospectively, by means of retention, we may understand the A of the initial sonority in m. 1 as a dissonant upper neighbor tone, which resolves down to the tonic G in m. 4.

Example 1 provides a voice-leading graph of the first stanza (mm. 1–6). The frequent and overlapping repetition of the “upper neighbor-tone motive” is shown in the graph, as well as the theoretical resolution of the dissonant E in m. 5, which does resolve (in a lower octave) within the piano right-hand part. The voice-leading graph corroborates the C major tonal resolution of the first stanza in m. 6, although the dissonant A as an upper neighbor tone is also reestablished in m. 6.

Before continuing with a discussion of the second and third stanzas, I would like to reflect upon the general character of Price’s setting of Hughes’s poem. Having read the poem before listening to the song for the first time, I was greatly surprised by the apparent style and general affect of the musical text. The poem, at least as I interpreted it, was a brooding and sarcastic (possibly masochistic) expression of racial and perhaps homophobic self-hatred. The first-person narrator, in my reading, might be the same conscious entity as the second-person “dark virgin,” whom the narrator feels the need to “hide” and to eventually “annihilate.” Having understood the poem in this way, I was baffled by the cheerfully triumphant cadences and the unmitigated major-mode tonality of the setting by Price. An investigation of the deeper layers of parallelism within the voice-leading structure of the song reveals that a more nuanced understanding of Price’s setting of the poem is possible if multiple strands of continuity are considered to be equally and simultaneously meaningful.

From a purely postmodern perspective, it is of course the reader who determines the meaning of the poem; however, while discerning the meaning of the poem alone (and not the song by Price) I will eliminate, at least temporarily, the “feminist” reading that requires a female first-person voice, as well as the “beautifully delicious love” description of the poem. (Price’s song may incorporate some element of these interpretations.) A consistent narrative persona, and therefore a unitary first-person voice can be realistically heard in many, if not all, of the poems in The Weary Blues.13“Like Blake’s Songs of Innocence and Experience, The Weary Blues contains several companion poems spoken by the same or by similar personae” (Skansgaard 2020, 69–70). Hughes was a student of William Blake’s poetry and at least one of Hughes’s poems includes recognizable similarities to a possible model work composed by Blake (Skansgaard 2020, 69). That persona is ostensibly male and Black. The “proem” to The Weary Blues (a portmanteau of “prologue” and “poem”) begins with the words “I am a Negro” and continues soon thereafter with the consecutive lines “The Belgians cut off my hands in the Congo” and “They lynch me now in Texas” (Hughes 2020 [1926], 1).14The line “To annihilate thy body” from “Songs to the Dark Virgin” seems at first, especially in consideration of the past four hundred years of American history (Emmett Till, James Byrd Jr., George Floyd, and thousands of lynchings in the southern United States) to more directly reference the violent destruction of the Black male body than the pleasure of a female orgasm; however, the full conceit may be to “annihilate the virgin body,” which could have several “subtly illusive” meanings. We should perhaps also consider the ways in which African culture was “annihilated” during the period of slavery. Although specific meanings are never certain in Hughes’s poetics, the first-person speaker is apparently a Black male.

For many critics, the first-person voice, together with its metonymical persona, dominate the texture of The Weary Blues. According to Kevin Young, Hughes managed to “take Whitman’s American ‘I’ and write himself into it … the volume ends with one of the more memorable lines of the century … ‘I, too, am America” (Hughes 2020 [1926], xvii).15Hughes “sensed the affinity between the inclusive ‘I’ of Whitman and the inclusive ‘I’ of the spirituals” (Hutchinson 1995, 415). David Chinitz (2013, 43) has observed that the first-person perspective of The Weary Blues may sometimes represent a collective voice “the product of a romantic essentialism, evoking as it does a single racial mind or ‘soul.’” I suggest that the ubiquity of the first-person voice is clear in The Weary Blues, but that it only occasionally is intended as a metaphor. When Hughes writes “I am a Negro,” he is representing the race as a whole, but he is equally making the observation that the individual first-person narrator is a Black male.16Carl Van Vechten’s introduction to the original edition of The Weary Blues includes the perception that “Always … his [Hughes’s] stanzas are subjective, personal” (Hughes 2020 [1926], xxv). DuBose Heyward (1986 [1926], 44) also observed that Hughes’s poetry was “[always] intensely subjective.” Heyward’s comment appeared in his article “The Jazz Band’s Sob,” which originally appeared in the New York Herald Tribune Books

While interpreting the poem we must remember that the topic and setting of The Weary Blues is the realistic portrayal of “present-day African Americans in gritty urban areas” (Peters 1995, 75). We are introduced to a succession of jazz bands, exhausted musicians, prostitutes, “nude dancers, beggar boys, cabaret singers, young sailors, and everyday folk.”17The quotation is from Kevin Young’s foreword to the 2020 edition (Hughes 2020 [1926], xvi). Young also observes that “jazz bands and vulgarity weren’t easily found in poetry before Hughes wrote of them” (Hughes 2020 [1926], xiv). The narrative persona who is moving through this world of the Harlem Renaissance during the peak of the “jazz age” is an almost exact replica of the authorial persona of Hughes himself. A summary of the poet’s adventures in Africa, Europe, and the United States was included in the original 1926 edition of The Weary Blues. As Kevin Young observes, “Hughes reveled in the gray (and gay) he saw around him in his travels to Mexico, his exile in Paris, and home in his adopted Harlem” (Hughes 2020 [1926], xv). Considering all of this, we must assume that the first-person narrator is a Black male, though other interpretations always remain a possibility.18There is at least one poem in The Weary Blues, “Mother to Son” (Hughes 2020 [1926], 89), which is clearly spoken by a female voice; however, even in this poem the point of view of the general collection’s authorial persona is still present, since the poem is addressed to an African American male. The Weary Blues was dedicated to Hughes’s mother.

If the race and gender of the first-person voice is somewhat determinable in Hughes’s poem, the identity of the “dark virgin” may not be as easily resolved from a close reading of the text.19“Particularly in his poetry, Hughes produces a multiplicity of meanings, works with an ambiguity of terms, and … thereby [opens] up spaces … for gay readings” (Schwarz 2003, 72). Penelope Peters (1995) has proposed two contrasting interpretations of the poem, one in which a male speaker is addressing a woman, and one in which the “dark virgin” is a woman addressing herself, as if looking into a mirror.20“Because society (white society) has made her abhor her dark skin, she first tries to adorn herself with jewels; alas, they do not conceal enough of her loathsome dark flesh. Next, she tries to hide it in silken garments; still not sufficiently disguised, she is left with no recourse but to annihilate her body in fire. Unable to change her skin colour, in self-loathing she destroys herself. In other words, rather than having written a love poem, Hughes comments on the self-destruction of so many African Americans by their surrender to the desperation of their predicament” (Peters 1995, 80). I believe that Peters has found the essential dichotomy of the poem’s intended meaning. The “flickering reality” that the reader may never fully resolve or collapse is the question of the distance between the first-person voice and the “dark virgin.” Is the “dark virgin” an object of desire or veneration, or is the “dark virgin” the speaker himself? It seems that Peters assumed the speaker must be female if “she” is the dark virgin, but the only language that supports a female gender for the “virgin” is the word “virgin” itself, which is only found in the title, and not the text of the poem.21For a discussion of Hughes and the issue of sexual identity see Aldrich (2001, 200), Schwarz (2003, 68–88), Rampersad (1986, 69), and Rampersad (1988, 336). Harold Bloom (1999, 9) has suggested that “Whatever his sexual orientation (and it remains ambiguous), Hughes chose personal solitude, which is frequently the burden of his lyrics.” It is perhaps equally possible that the apparently feminine description of the “virgin” is a metaphorical element of the gender fluidity associated with this particular first-person voice.22A. B. Christa Schwarz (2003) has explored Hughes’s use of the word “virgin” in his short story “The Little Virgin” (Hughes 1996 [1926], 17–23), which was originally published in the Messenger (a literary journal associated with the Harlem Renaissance) in 1926, the same year in which The Weary Blues appeared in print. In the short story, a sailor “is given an insulting nickname by the crew—'Little Virgin’—which underlines his ‘inferior’ sexual status … Hughes ‘unmanly’ sailor is persecuted by other sailors who address him as ‘pink angel’ and ridicule him by calling him ‘Mama’s nice baby’ in a falsetto voice … The conclusion … seems clear: The effeminate man is not fit to be part of a ship’s ‘manly’ crew” (Schwarz 2003, 82). Similar to the title character in the short story, Hughes had served in the merchant marine and experienced an array of vicissitudes during his time as a sailor. It seems possible that Hughes is using the term “virgin” as a disparaging, shameful, and homophobic term of self-loathing in the poem “Songs to the Dark Virgin” in the same way that the term is used as an insulting slur against the protagonist in the short story published during the same year.

The meaning of these same elements may be different, or may be interpreted differently, in Price’s song than in Hughes’s poem. The authorial persona must now, to some extent, embody the possibility of a Black woman speaking in her own voice. The vulgarity, hostility, and pessimism of Hughes’s original text must be reconsidered and the caustic and heart-wrenching ironic tone, which becomes almost the standard mode of discourse in parts of The Weary Blues,23See the penultimate section of the collection with the title “Shadows in the Sun” (Hughes 2020 [1926] 66–77), especially the poem “Suicide’s Note.” Alain Locke (1986 [1926], 44) described Hughes’s use of language in The Weary Blues as “the entire absence of sentimentalism: the clean simplicity of speech, the deep terseness of mood.” Lock’s review of The Weary Blues was originally published in poetry magazine Palms. may perhaps be set aside for a new understanding of this one poem on its own terms.

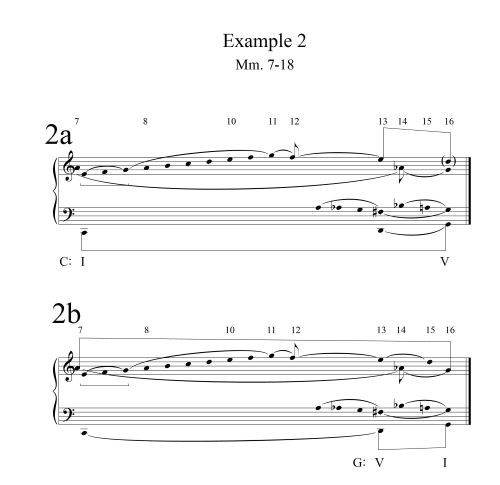

Example 2 provides two contrasting voice-leading interpretations of the second stanza (mm. 7–18). The frequent and overlapping repetitions of the “upper neighbor-tone motive” continue in the second stanza (translational parallelism), but this time the motivic pattern is intensified by the slightly more dissonant harmonization of the melodic E on the word “hold” in the vocal part in m. 13 and especially by the A-flat on the word “hide” in m. 14. Both of these important pitches are presented as members of the extended tertian sonorities in which they occur, but clearly function as dissonant appoggiaturas at a slightly deeper level of the voice-leading foreground, again emphasizing the importance of the “upper neighbor-tone motive” and its constant temporal translation. I take notice that Price’s treatment of the word “hide” in m. 14 seems to demonstrate that her understanding of the poem is not entirely jovial and optimistic. Example 2a represents the second stanza as concluding with a structural half cadence in the key of C major, while Example 2b interprets the entire second stanza as a structural auxiliary cadence in the key of G major.24The term “auxiliary cadence” refers to an incomplete progression, usually at the background or deep middleground level, that ends on the tonic. See Charles Burkhart’s (1990) article “Departures from the Norm in Two Songs from Schumann’s Liederkreis.”

We may now perhaps reconsider the feminist interpretation of the song proposed by Elizabeth Durrant (2021) and others. In a letter to the conductor Serge Koussevitzky from 1943, Price wrote that “To begin with I have two handicaps—those of sex and race. I am a woman; and I have some Negro blood in my veins” (Brown 2020, 186). From this statement it may be understood that Price would have known several meanings for the poem’s reference to “hiding the Black body.” Beyond the simple concept of modesty, which is itself probably a feminist interpretation, it also conveys various levels of meaning related to the need to hide or conceal one’s identity.25When Price began her studies at the New England Conservatory, she incorrectly listed her place of birth as Mexico, perhaps as an effort to hide her racial identity (Brown 2020, 54). The letter continues with “Knowing the worst, then, would you be good enough to hold in check the possible inclination to regard a woman’s composition as long on emotionalism but short on virility and thought content” (Brown 2020, 186).

The interpretation of the words “hide thy body” may have been different for Hughes than for Price, but for the implied authorial first-person personae of either the poem or the song it is actually a complex web of meanings that is suggested, a texture of signification (or “signifyin(g)”) that itself describes the concept of concealment. Price must have understood the vulgarity, irony, and cynicism of Hughes’s original text, but perhaps the inherent dichotomy of the text (derived from the obscure identity of the “dark virgin”) attracted Price to the possibility of layering an additional level of meaning, in this case derived from a woman’s perspective, upon a text that was already both “hiding” its meaning and “about the concept of hiding,” or concealment, itself. The musical setting of this “subtly illusive” poem, especially its multivalent harmonic structure, thus represents and exemplifies this process of concealing the “concept of hiding.”26“The tension created by symbolic references in this work are not unique—indeed, it is the vivifying attribute of a good poem—but the precise version of symbolic tension that follows from the rival interpretations defines the alienation of the African American experience. The impact of the message is overwhelming; for, the alienation simultaneously expresses the African American collective experience and provides the reason for the layered meanings—the need to conceal the sense of despair from an alien society. Hughes’s motivation for concealing the feelings and emotions of the dark virgin in an apparent love-ballad springs from the same source that compelled African Americans to use a private vocabulary in the plantation songs” (Peters 1995, 81).

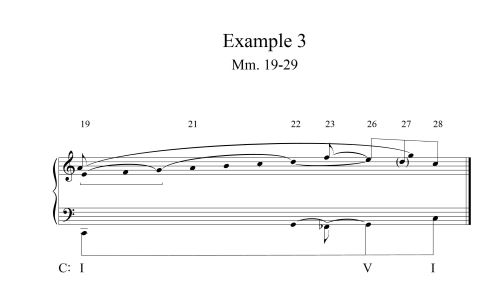

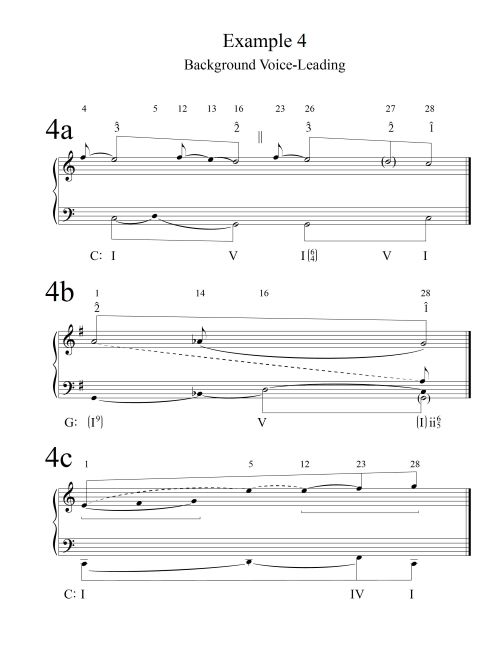

Example 3 provides a voice-leading graph of the third stanza (mm. 19–29) and Example 4 provides three different interpretations of the complete song. In Example 4a the “upper neighbor-tone motive” is expanded to the background level (prolongational parallelism) by the emphasis on the word “annihilate” in m. 23. The F in the vocal line on the stressed middle syllable of “annihilate,” probably the most important word in the poem, creates a background level appoggiatura to the E in m. 26 on the word “dark.”27The F in m. 23 is, of course, equivalent in Example 4a to the F structural appoggiatura in m. 4. In Example 4b the complete song is represented as a background-level auxiliary cadence in the key of G. The analysis in Example 4b derives primarily from perceiving a concluding G in the vocal line in m. 28 (indicated as an optional higher pitch for the vocalist in the original 1941 publication) as the background-level resolution for the dissonant A in m. 1, while also significantly reducing the importance of the apparent C major tonic in m. 28 (which still includes a dissonant and destabilizing A in the harmony). In Example 4c, both translational parallelism and prolongational parallelism may be observed in the crucial statement of the word “annihilate” in m. 23, as the F functions as the root of a structural subdominant, while the G in m. 28 represents the completion of the “rising melodic third motive,” presented originally within the foreground of m. 2. The background sketches provided in Examples 4a and 4c represent different and conflicting interpretations of the important F in m. 23, the setting of the crucial word “annihilate” in Hughes’s poem.

Multi-Linear Continuity

The multi-level motivic repetitions that create the prolongational parallelism between the foreground-level appearances of the “upper neighbor-tone motive” (or the “rising melodic third” motive) and the background-level expression of the same motive(s) represent a form of multi-linear continuity, since the subjective listener must actively perceive the similarity between the motivic repetitions at entirely different voice-leading levels in order for the motivic parallelism to be identified. Recognizing this motivic correspondence requires both retention and protention, as well as the active grouping of non-consecutive elements into structural continuities. The process of incorporating the various levels and statements of the motive into a single structural idea is a form of non-linear continuity, since each statement of the motive is unique in relation to its own specific expression.

I use the term non-linear to describe the consideration of a musical work independent of any aspect of linear continuity, that is, the musical work as a whole, as if all of the inherently successive or contrapuntal elements of the work were to take place at the same time.28 I am suggesting that the non-linear understanding of a musical work would imply the kind of perceptual consciousness that Maurice Merleau-Ponty (2012 [1945], 34–38) describes by the term “reflective analysis,” an a posteriori mode of intentionality directed away from the subject itself, rather than the subjective experience of temporal continuity that Edmund Husserl (1964 [1928], 43) describes as internal time consciousness. “But when I think of something now, the guarantee of a non-temporal synthesis is neither sufficient nor even necessary to ground my thought. It is now, in the living present, that the synthesis must be produced, otherwise thought would be cut off from its transcendental premises” (Merleau-Ponty 2012 [1945], 130). The term multi-linear refers to the listener’s subjective process for the reconstruction of linear continuities from a musical text that is fragmented or discontinuous in terms of immediately perceptible linear continuity. Since the restructuring of linear continuity from constituent and often ambiguous elements of musical form is a creative process, there are usually a plurality of possible linear continuities that may be reformulated by the listener, hence the term multi-linear continuity.29My use of the terms non-linear and multi-linear is largely derived from Jonathan D. Kramer’s (1988) use of these terms in The Time of Music.

From a non-linear point of view, all of the motivic perceptions identified in the voice-leading reductions (in the previous examples) may be understood to exist simultaneously. Since each of these perceptions is derived from its own musical event, they are each unique in terms of syntactic or functional meaning, yet they share the larger source-context of the work as a whole, and therefore, at least in a non-linear sense, equally exist as possible perceptions within the listener’s understanding of the song. Although some of the perceptions seem to logically eliminate the validity of other perceptions, they exist together as non-linear continuities.

From a multi-linear point of view, the motivic perceptions identified in the voice-leading reductions (in the previous examples) represent a group of possible events from which the listener may subjectively reconstruct a number of potential musical continuities. The recognition or understanding of these potential linear continuities is a subjective process, since it is determined by which perceptions the listener chooses to include within any particular reconstruction of the work. Just as some perceptions seem to eliminate the possibility of other perceptions, some of the possible linear reconstructions of continuity seem to eliminate other possible continuities.

I believe the most important aspect of multi-linear continuity in “Songs to the Dark Virgin” is that the pattern of hidden motivic repetition serves to obscure the fundamental voice-leading structure of the work, thereby establishing concealment as a central idea, consistent with Gates’s (1988) literary metaphor of “signifyin(g),” and similar to the element of ambiguity in Hughes’s original poem. Joseph Dubiel (1994) has analyzed the competing tonal centers of D and B-flat in the first movement of Johannes Brahms Piano Concerto No. 1 and described the B-flat sonority as “inflecting” the tonic D Minor and the tonic D Minor as also “inflecting” the contending B-flat sonority.30Dubiel’s analysis of the first movement from the Brahms D-Minor Piano Concerto differs from my analysis of “Songs to the Dark Virgin” because of Dubiel’s (1994, 85) assertion that the listener must not maintain “both interpretations of the same objects at the same time.” I propose that the listener or analyst may maintain both interpretations in a non-linear relationship with each other, or as components within different conflicting multi-linear analyses. In my interpretation of “Songs to the Dark Virgin,” I suggest that the dissonant A in m. 1 inflects and obscures (conceals) the tonic C major sonority, establishing both the importance of the “upper neighbor tone motive” (Example 1) and the possibility of an alternative background-level structure in which the A is a member of the primary dominant in the key of G major (Example 4b).31“The two possible analyses of the expanded chord correspond with the two readings—the double meaning of Hughes’s poem and the Janus-like complexity of the sonority also mirrors Price’s attempt to reconcile her natural musical heritage with the European musical tradition of her formal studies” (Peters 1995, 81–83). The “two possible analyses of the chord” identified by Peters are slightly different from the two possible functions for the sonority that I have just implied; however, Peter’s two meanings for the poem are very similar to my description of the two contrasting possible interpretations of “Songs to the Dark Virgin” as a literary text.

The A in the first measure of the piano right-hand part, which serves as an upper neighbor tone to the G in m. 4, is obscured and concealed by the F upper neighbor tone that resolves to an E in m. 4 of the vocal line. This delayed resolution of the A as an upper neighbor tone perhaps also functions as a basic motive, or Grundgestalt,32In a description of his concept of Grundgestalt, Arrnold Schoenberg (2010 [1975] [1931], 290) observed that “whatever happens in a piece of music is nothing but the endless reshaping of a basic shape … there is nothing in a piece of music but what comes from the theme, springs from it and can be traced back to it; to put it still more severely, nothing but the theme itself … all the shapes appearing in a piece of music are foreseen in the ‘theme.’” for the song as a whole. The motion from A to G is amplified in the second stanza (translational parallelism) by the prominent A-flat in m. 14 of the vocal line on the word “hide,” which resolves to the G in m. 16. There is also a small-scale repetition (through subjective retention) of the A-flat to G motive in the left-hand piano part in m. 12. I believe that the A as an upper neighbor-tone motive, may even be transferred to the background level as the A-flat in m. 14 resolves to the final G in the vocal line in m. 28 (Example 4b).

The structural function of the pitch E in the vocal line is also obscured and concealed by the pattern of hidden motivic repetition. If the song is to be interpreted as a tonal expression in the key of C major, then E must function as the structural third scale degree of the tonic within the melody line, but the actual role of E in the vocal line is often ambiguous or uncertain. In the first stanza, the E in m. 5 on the word “feet” is undermined by its foreground appearance as the ninth of a chord built on D. In the second stanza the prominent E on the word “hold” in m. 13 is again harmonized as the ninth of a chord built on D (this time a chord that includes the pitch F-sharp, rather than F-natural). In the third stanza the tonic function of the E on the word “dark” in m. 26 is greatly weakened by its foreground harmonization as part of an E minor chord in first inversion.

As shown in Example 4, it may be possible to suggest alternative background voice-leading structures (multi-linear continuities) for the musical text of “Songs to the Dark Virgin.” The analysis in Example 4a is a divided form in the key of C major, while Example 4b describes a background-level auxiliary cadence in the key of G major, with the A in m. 1 leading directly to the G in m. 26. In Example 4c the vocal line’s opening motivic gesture in m. 2 (E, F, G) is transferred to the background level through prolongational parallelism. The important aspect of these conflicting background structures is that they each work to “conceal” the other possible background analyses. According to Gates (1988, 86) the process of “signifyin(g)” requires the writer, composer, or creator to suggest an “absent meaning ambiguously ‘present’ in a carefully wrought statement.”33“Thinking about the black concept of Signifyin(g) is a bit like stumbling unaware into a hall of mirrors: the sign itself appears to be doubled, at the very least, and (re)doubled upon ever closer examination” (Gates 1988, 49).

The most common representation of the term “signifyin(g)” describes the practice of apparent duplicity when African Americans sang about the “liberation of the Jews from Egypt” or the “freedom from sin given by Christ” to secretly describe aspects of the real-world suffering of the enslaved population.34“[Black] people have been Signifyin(g), without explicitly calling it that, since slavery” (Gates 1988, 74). In a much more complex way, Hughes’s poem creates an ambiguous text that also deceives the (white) reader with an “acceptable” surface-level reading about an ode to the beauty of a Black “beloved,” while secretly supplying hidden levels of meaning about “Blackness” and “annihilation.”35“The text, in other words, is not fixed in any determinate sense; in one sense, it consists of the dynamic and indeterminate relationship between truth on one hand and understanding on the other” (Gates 1988, 29). Gates is specifically addressing a story from Yoruba mythology, but his description may equally apply to the “signifyin(g)” in Hughes’s poem. Gates (1988, 109–10) also discusses the treatment and manipulation of “signifyin(g) in Hughes’s poem “Ask Your Mama.” Price’s art song takes this double meaning and adds an additional layer of “signifyin(g)” through the apparent triumph of European heterosexual tonal music—although the actual harmonic structure may be, on closer inspection, obscure and unsettled. To complicate this veiled “signifyin(g)” even further, the poem and the song are both actually concealing the concept of “hiding” itself, which perhaps represents the central conceit of the disguised subtext. Hiding the “Black body” is certainly one of the oldest African American tropes—and one of the oldest tropes about “Blackness.” The creation of this complex art song about “Blackness” using the specialized language of Western classical music is, of course, the supreme act of “signifyin(g)” by Price.

A central aspect of “signifyin(g)” is the adoption of an emotional affect that is contrary to the meaning of the subtextual message.36Henry Louis Gates (1988, 73) quotes Frederick Douglass’s explanation that the slaves “would sing the most pathetic sentiment in the most rapturous tone, and the most rapturous sentiment in the most pathetic tone.” The quotation is from Douglass’s (1963 [1845], 13–14) Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave, Written by Himself. Gates (1988, 73) observes that “The great mistake of interpretation occurred because the blacks were using antiphonal structures to reverse their apparent meaning, as a mode of encoding for self-preservation.” Hughes’s poetry conspicuously displays this creative strategy, especially noticeable in the poet’s very frequent use of the words “laugh” and “laughter.”37In the poem “The Jester” from The Weary Blues, Hughes (2020 [1926], 35) wrote the consecutive lines “Tears are my laughter” and “Laughter is my pain.” This technique of expressive reversal is reflected in Price’s seemingly jubilant and joyful music in “Songs to the Dark Virgin,” which seems to convey a subtext about adversity and intolerance.38Gates (1988, 98) specifically describes irony as a potential aspect of “signifyin(g).” Gates (1988, 134) also explores the possibility of “signifyin(g)” as a possible element of a musical work or a musical performance, for example in the music of Count Basie and other jazz musicians who create “phrases that overlap the underlying rhythmic and harmonic structures.” There is also a description of the intertextual aspect of “signifyin(g)” in the literature of contemporary African American writers, perhaps similar to Price’s “re-writing” of Hughes’s poem. “Writers Signify upon each other’s texts by rewriting the received textual tradition. This can be accomplished by the revision of tropes. This sort of Signifyin(g) revision serves, if successful, to create a space for the revising text.” (Gates 1988, 135).

Although some writers have identified traditionally “Black” musical elements in Price’s setting of “Songs to the Dark Virgin,”39These idiomatically “Black” musical aspects would include the sustained pitch at the end of each vocal phrase (Peters 1995, 81), the frequent use of “jazz harmonies” such as extended tertian and dissonant ninth chords (Peters 1995, 80), the texture of a lyrical vocal line accompanied by large rolled chords [for example in mm. 14–18] that are typical of “church hymns and … the Negro Spiritual (Mashego 2010, 29–34), the repeated refrain “Thou dark one” at the end of each verse (Mashego 2010, 34), or the generally religious and penitential tone of the poem (especially its reference to the Virgin Mary) that references the “importance of the church within the black community” (Smith 2007, 89–90). I believe the reason for applying Gates’s analytical theory of “signifyin(g)” to this work derives more from the meaning of the text than the nature of the musical setting. For all of the text’s various possible interpretations, the concept of “Blackness” is central, as well as the idea of “hiding or annihilating” that “Blackness.” Since concealing “Blackness” is one form of “signifyin(g),” the poem, the song, and its harmonic structure seem to not only “signify,” but to be about “signifyin(g).” As Ayana Smith has observed, “Signifyin goes beyond imitation; however, to signify, the creative artist must trope in a way that comments upon the original in a new interpretive context” (Smith 2005, 148).40“Signifying, therefore, creates a new subtext through the intersection of the original with the trope that is analogous to the physical and metaphorical nature of the crossroads” (Smith 2005, 148).

Conclusion

In this article I have attempted to demonstrate that the continuous pattern of concealment in “Songs to the Dark Virgin,” primarily as it may be recognized through voice-leading structures of hidden repetition, translational parallelism, and prolongational parallelism, work to establish the kind of expressive metaphor that Gates (1988) describes as “signifyin(g).” Since more than one statement of the concealed “upper neighbor-tone motive” may be in progress at any one specific temporal location within the musical text, a non-linear or multi-linear approach to musical perception must also be recognized by the subjective listener in order to understand the concealed metaphorical expression. The idea of concealment also applies to the meaning of the poetic text itself, and to the layers of possible meaning that Price’s musical setting may create. The identity of the first-person voice and the second-person persona (whom the first-person voice overtly desires to “hide” in the second stanza) are also concealed through ambiguous textual devices. A possible solution to the concealed identity of the second-person “dark virgin” could be that the second person pronoun, “thou,” should be taken at face value, and therefore the song and the poem might be understood as directly addressing “you,” the reader—“Thou dark one.”

[1] The most important biographical study of Florence Price is Ray Linda Brown’s (2020) The Heart of a Woman: The Life and Music of Florence B. Price. Within approximately the past fifteen years, a number of theses and dissertations have appeared on the subject of Price and her music, including those of Scott Farrah (2007), Bethany Smith (2007), Sarah Peebles (2008), Shana Mashego (2010), Amy Broadbent (2016), Erin Hobbs (2017), Marquese Carter (2018), Meng-Chieh Hsieh (2019), Daniel Hunter (2019), Christine Jobson (2019), Samantha Ege (2020), and Elizabeth Durrant (2021). There are also some research projects that considerably predate the recent revival of interest in Price. These sources include the monograph by Mildred Green (1983) and the thesis of Carren Moham (1997)

[2] The earliest known manuscript for the song is dated April 26, 1935. See the description of this manuscript source provided by John Michael Cooper in his introduction to the Schirmer critical edition (Price 2021, iii).

[3] “Songs to a Dark Virgin” has been published in numerous anthologies and the complete musical text may be easily found through an internet search. The original 1941 publication by Schirmer is reproduced in the thesis of Bethany Smith (2007, 111–14). A critical edition, edited by John Michael Cooper, has recently been issued by Schirmer (Price 2021).

[4] Similar to Price’s musical text, Hughes’s poem “Songs to the Dark Virgin” appears in many anthologies, including The Collected Poems of Langston Hughes (Hughes 1994, 61–62), and may be easily found through an internet search. The poem is reproduced in the thesis of Bethany Smith (2007, 67–68).

[5] The “Harlem Renaissance,” also known as the “Negro Renaissance” or the “New Negro Movement,” was a revival of African American culture, especially intellectual and artistic expression, that took place primarily in New York City and other areas of the northern and midwestern United States during the 1920s and 1930s. Hughes was one of the central literary figures of the “Harlem Renaissance.”

[6] In his dissertation, which focuses on the semiotic analysis of symphonic music by African American composers, Scott Farrah (2007, 18–19) paraphrases the definition of “signifyin(g)” suggested by Samuel A Floyd (1995, 96) as “it is a way of saying one thing and meaning something else using Afro-American stylistic tropes.”

[7] See the discussion of symbolic musical references in this song provided by Green (1983, 35–36), Smith (2007, 89–95), and Brown (2020, 225–26).

[8] “To translate is to ‘transfer’ or ‘transport’ a body or form of energy from one point of space to another without rotation (or from one person, place or condition to another)” (Kielian-Gilbert 2003, 69).

[9] In some musical works the structural voice leading of an opening motivic gesture may resemble the large-scale voice-leading reduction of an entire movement or an entire formal section. Charles Burkhart (1978) provides an explanation of this process, described by the term multi-level motivic repetition. A very similar pattern of prolongational parallelism between small and large scale tonal progressions is the subject of Irene Montefiore Levenson’s (1981) dissertation, “Motivic-Harmonic Transference in the Late Works of Schubert: Chromaticism in Large and Small Spans.”

[10] Retention and protention are important aspects of Edmund Husserl’s (1964 [1928]) phenomenology of temporality. See the discussion of Husserl in David Lewin’s (2006 [1986], 53–67) article “Music Theory, Phenomenology, and Modes of Perception.”

[11]Although the original Schirmer edition of “Songs to the Dark Virgin” (Price 1941) is in the key of A-flat major, the Schirmer critical edition (Price 2021), edited by John Michael Cooper and based on a manuscript completed in 1935, is in the key of C major. The two versions are exact transpositions of each other, with the exception of a few orthographic elements in the piano part, such as beaming, and the absence of the optional higher notes in the voice part at the end of the song in the C major version (which are included in the 1941 version). The analytical discussion and examples in this article will follow the new critical edition, edited by John Michael Cooper, except when specifically referencing aspects of the original 1941 published version.

[12] I use the term concealment to suggest the process of “saying one thing and meaning another,” especially through the use of established African American tropes, or perhaps also through established tropes about “Blackness.”

[13]“Like Blake’s Songs of Innocence and Experience, The Weary Blues contains several companion poems spoken by the same or by similar personae” (Skansgaard 2020, 69–70). Hughes was a student of William Blake’s poetry and at least one of Hughes’s poems includes recognizable similarities to a possible model work composed by Blake (Skansgaard 2020, 69).

[14] The line “To annihilate thy body” from “Songs to the Dark Virgin” seems at first, especially in consideration of the past four hundred years of American history (Emmett Till, James Byrd Jr., George Floyd, and thousands of lynchings in the southern United States) to more directly reference the violent destruction of the Black male body than the pleasure of a female orgasm; however, the full conceit may be to “annihilate the virgin body,” which could have several “subtly illusive” meanings. We should perhaps also consider the ways in which African culture was “annihilated” during the period of slavery.

[15] Hughes “sensed the affinity between the inclusive ‘I’ of Whitman and the inclusive ‘I’ of the spirituals” (Hutchinson 1995, 415).

[16]Carl Van Vechten’s introduction to the original edition of The Weary Blues includes the perception that “Always … his [Hughes’s] stanzas are subjective, personal” (Hughes 2020 [1926], xxv). DuBose Heyward (1986 [1926], 44) also observed that Hughes’s poetry was “[always] intensely subjective.” Heyward’s comment appeared in his article “The Jazz Band’s Sob,” which originally appeared in the New York Herald Tribune Books.

[17] The quotation is from Kevin Young’s foreword to the 2020 edition (Hughes 2020 [1926], xvi). Young also observes that “jazz bands and vulgarity weren’t easily found in poetry before Hughes wrote of them” (Hughes 2020 [1926], xiv).

[18] There is at least one poem in The Weary Blues, “Mother to Son” (Hughes 2020 [1926], 89), which is clearly spoken by a female voice; however, even in this poem the point of view of the general collection’s authorial persona is still present, since the poem is addressed to an African American male. The Weary Blues was dedicated to Hughes’s mother.

[19] “Particularly in his poetry, Hughes produces a multiplicity of meanings, works with an ambiguity of terms, and … thereby [opens] up spaces … for gay readings” (Schwarz 2003, 72).

[20] “Because society (white society) has made her abhor her dark skin, she first tries to adorn herself with jewels; alas, they do not conceal enough of her loathsome dark flesh. Next, she tries to hide it in silken garments; still not sufficiently disguised, she is left with no recourse but to annihilate her body in fire. Unable to change her skin colour, in self-loathing she destroys herself. In other words, rather than having written a love poem, Hughes comments on the self-destruction of so many African Americans by their surrender to the desperation of their predicament” (Peters 1995, 80).

[21] For a discussion of Hughes and the issue of sexual identity see Aldrich (2001, 200), Schwarz (2003, 68–88), Rampersad (1986, 69), and Rampersad (1988, 336). Harold Bloom (1999, 9) has suggested that “Whatever his sexual orientation (and it remains ambiguous), Hughes chose personal solitude, which is frequently the burden of his lyrics.”

[22] A. B. Christa Schwarz (2003) has explored Hughes’s use of the word “virgin” in his short story “The Little Virgin” (Hughes 1996 [1926], 17–23), which was originally published in the Messenger (a literary journal associated with the Harlem Renaissance) in 1926, the same year in which The Weary Blues appeared in print. In the short story, a sailor “is given an insulting nickname by the crew—'Little Virgin’—which underlines his ‘inferior’ sexual status … Hughes ‘unmanly’ sailor is persecuted by other sailors who address him as ‘pink angel’ and ridicule him by calling him ‘Mama’s nice baby’ in a falsetto voice … The conclusion … seems clear: The effeminate man is not fit to be part of a ship’s ‘manly’ crew” (Schwarz 2003, 82). Similar to the title character in the short story, Hughes had served in the merchant marine and experienced an array of vicissitudes during his time as a sailor. It seems possible that Hughes is using the term “virgin” as a disparaging, shameful, and homophobic term of self-loathing in the poem “Songs to the Dark Virgin” in the same way that the term is used as an insulting slur against the protagonist in the short story published during the same year.

[23] See the penultimate section of the collection with the title “Shadows in the Sun” (Hughes 2020 [1926] 66–77), especially the poem “Suicide’s Note.” Alain Locke (1986 [1926], 44) described Hughes’s use of language in The Weary Blues as “the entire absence of sentimentalism: the clean simplicity of speech, the deep terseness of mood.” Lock’s review of The Weary Blues was originally published in poetry magazine Palms.

[24] The term “auxiliary cadence” refers to an incomplete progression, usually at the background or deep middleground level, that ends on the tonic. See Charles Burkhart’s (1990) article “Departures from the Norm in Two Songs from Schumann’s Liederkreis.”

[25] When Price began her studies at the New England Conservatory, she incorrectly listed her place of birth as Mexico, perhaps as an effort to hide her racial identity (Brown 2020, 54).

[26] “The tension created by symbolic references in this work are not unique—indeed, it is the vivifying attribute of a good poem—but the precise version of symbolic tension that follows from the rival interpretations defines the alienation of the African American experience. The impact of the message is overwhelming; for, the alienation simultaneously expresses the African American collective experience and provides the reason for the layered meanings—the need to conceal the sense of despair from an alien society. Hughes’s motivation for concealing the feelings and emotions of the dark virgin in an apparent love-ballad springs from the same source that compelled African Americans to use a private vocabulary in the plantation songs” (Peters 1995, 81).

[27] The F in m. 23 is, of course, equivalent in Example 4a to the F structural appoggiatura in m. 4.

[28] I am suggesting that the non-linear understanding of a musical work would imply the kind of perceptual consciousness that Maurice Merleau-Ponty (2012 [1945], 34–38) describes by the term “reflective analysis,” an a posteriori mode of intentionality directed away from the subject itself, rather than the subjective experience of temporal continuity that Edmund Husserl (1964 [1928], 43) describes as internal time consciousness. “But when I think of something now, the guarantee of a non-temporal synthesis is neither sufficient nor even necessary to ground my thought. It is now, in the living present, that the synthesis must be produced, otherwise thought would be cut off from its transcendental premises” (Merleau-Ponty 2012 [1945], 130).

[29] My use of the terms non-linear and multi-linear is largely derived from Jonathan D. Kramer’s (1988) use of these terms in The Time of Music.

[30]Dubiel’s analysis of the first movement from the Brahms D-Minor Piano Concerto differs from my analysis of “Songs to the Dark Virgin” because of Dubiel’s (1994, 85) assertion that the listener must not maintain “both interpretations of the same objects at the same time.” I propose that the listener or analyst may maintain both interpretations in a non-linear relationship with each other, or as components within different conflicting multi-linear analyses.

[31] “The two possible analyses of the expanded chord correspond with the two readings—the double meaning of Hughes’s poem and the Janus-like complexity of the sonority also mirrors Price’s attempt to reconcile her natural musical heritage with the European musical tradition of her formal studies” (Peters 1995, 81–83). The “two possible analyses of the chord” identified by Peters are slightly different from the two possible functions for the sonority that I have just implied; however, Peter’s two meanings for the poem are very similar to my description of the two contrasting possible interpretations of “Songs to the Dark Virgin” as a literary text.

[32] In a description of his concept of Grundgestalt, Arrnold Schoenberg (2010 [1975] [1931], 290) observed that “whatever happens in a piece of music is nothing but the endless reshaping of a basic shape … there is nothing in a piece of music but what comes from the theme, springs from it and can be traced back to it; to put it still more severely, nothing but the theme itself … all the shapes appearing in a piece of music are foreseen in the ‘theme.’”

[33] “Thinking about the black concept of Signifyin(g) is a bit like stumbling unaware into a hall of mirrors: the sign itself appears to be doubled, at the very least, and (re)doubled upon ever closer examination” (Gates 1988, 49).

[34] “[Black] people have been Signifyin(g), without explicitly calling it that, since slavery” (Gates 1988, 74).

[35] “The text, in other words, is not fixed in any determinate sense; in one sense, it consists of the dynamic and indeterminate relationship between truth on one hand and understanding on the other” (Gates 1988, 29). Gates is specifically addressing a story from Yoruba mythology, but his description may equally apply to the “signifyin(g)” in Hughes’s poem. Gates (1988, 109–10) also discusses the treatment and manipulation of “signifyin(g) in Hughes’s poem “Ask Your Mama.”

[36] Henry Louis Gates (1988, 73) quotes Frederick Douglass’s explanation that the slaves “would sing the most pathetic sentiment in the most rapturous tone, and the most rapturous sentiment in the most pathetic tone.” The quotation is from Douglass’s (1963 [1845], 13–14) Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave, Written by Himself. Gates (1988, 73) observes that “The great mistake of interpretation occurred because the blacks were using antiphonal structures to reverse their apparent meaning, as a mode of encoding for self-preservation.”

[37] In the poem “The Jester” from The Weary Blues, Hughes (2020 [1926], 35) wrote the consecutive lines “Tears are my laughter” and “Laughter is my pain.”

[38] Gates (1988, 98) specifically describes irony as a potential aspect of “signifyin(g).” Gates (1988, 134) also explores the possibility of “signifyin(g)” as a possible element of a musical work or a musical performance, for example in the music of Count Basie and other jazz musicians who create “phrases that overlap the underlying rhythmic and harmonic structures.” There is also a description of the intertextual aspect of “signifyin(g)” in the literature of contemporary African American writers, perhaps similar to Price’s “re-writing” of Hughes’s poem. “Writers Signify upon each other’s texts by rewriting the received textual tradition. This can be accomplished by the revision of tropes. This sort of Signifyin(g) revision serves, if successful, to create a space for the revising text.” (Gates 1988, 135).

[39]These idiomatically “Black” musical aspects would include the sustained pitch at the end of each vocal phrase (Peters 1995, 81), the frequent use of “jazz harmonies” such as extended tertian and dissonant ninth chords (Peters 1995, 80), the texture of a lyrical vocal line accompanied by large rolled chords [for example in mm. 14–18] that are typical of “church hymns and … the Negro Spiritual (Mashego 2010, 29–34), the repeated refrain “Thou dark one” at the end of each verse (Mashego 2010, 34), or the generally religious and penitential tone of the poem (especially its reference to the Virgin Mary) that references the “importance of the church within the black community” (Smith 2007, 89–90).

[40] “Signifying, therefore, creates a new subtext through the intersection of the original with the trope that is analogous to the physical and metaphorical nature of the crossroads” (Smith 2005, 148).

Works Cited

Aldrich, Robert. 2001. Who’s Who in Gay & Lesbian History. New York: Routledge.

Bloom, Harold. 1999. Langston Hughes: Comprehensive Research and Study Guide. Broomall, Pennsylvania: Chelsea House.

Broadbent, Amy. 2016. “The Piano Teaching Pieces of Florence B. Price: A Pedagogical and Theoretical Analysis of 11 Late Elementary Piano Teaching Pieces.” M.M. thesis, Western Illinois University.

Brown, Ray Linda. 2020. The Heart of a Woman: The Life and Music of Florence B. Price. University of Illinois Press.

Burkhart, Charles. 1978. “Schenker’s ‘Motivic Parallelisms.’” Journal of Music Theory 22: 145–75.

———. 1990. “Departures from the Norm in Two Songs from Schumann’s Liederkreis.” In Schenker Studies, ed. Hedi Siegel, 146–64. Cambridge University Press.

Carter, Marquese. 2018. “The Poet and Her Songs: Analyzing the Art Songs of Florence B. Price.” D.M. diss., Indiana University.

Chinitz, David. 2013. Which Sin to Bear? Authenticity and Compromise in Langston Hughes. Oxford University Press.

Douglass, Frederick. 1963 [1845]. Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave, Written by Himself. New York: Doubleday.

Dubiel, Joseph. 1994. “Contradictory Criteria in a Work of Brahms.” In Brahms Studies, ed. David L. Brodbeck, 81–110. University of Nebraska Press.

Durrant, Elizabeth. 2021. “Chicago Renaissance Women Black Feminism in the Careers and Songs of Florence Price and Margaret Bonds.” M.A. thesis, University of North Texas.

Ege, Samantha. 2020. “The Aesthetics of Florence Price: Negotiating the Dissonances of a New World Nationalism.” Ph.D. diss., University of York.

Farrah, Scott. 2007. “Signifyin(g): A Semiotic Analysis of Symphonic Works by William Grant Still, William Levi Dawson, and Florence B. Price.” Ph.D. diss., Florida State University.

Gates, Henry Louis. 1988. The Signifying Monkey. Oxford University Press.

Green, Mildred. 1983. Black Women Composers. Boston: Twayne Publishers.

Heyward, Dubose. 1986 [1926]. “The Jazz Band’s Sob.” In Critical Essays on Langston Hughes, ed. Edward J, Mullen, 42–44. Boston: G. K. Hall & Co.

Hobbs, Erin. 2017. “Rehearsing Florence Price: A Closer Look at Her Symphony in E Minor.” M.M. thesis, California State University at Long Beach.

Hsieh, Meng–Chieh. 2019. “A Stylistic and Comparative Analysis of Selected Art Songs by Florence Price and Margaret Bonds.” D.M.A. thesis, University of Hartford.

Hughes, Langston. 1994. The Collected Poems of Langston Hughes. Edited by Arnold Rampersad. New York: Vintage Classics.

———. 1996 [1926]. “The Little Virgin.” In The Short Stories of Langston Hughes, ed. Akiba Sullivan Harper. New York: Hill and Wang.

———. 2020 [1926]. The Weary Blues. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Hunter, Daniel. 2019. “Florence B. Price’s Compositional Style in Song Settings of Paul Lawrence Dunbar’s Dialect Poetry: A Performance Guide.” D.M.A. thesis, University of Nevada at Las Vegas.

Husserl, Edmund. 1964 [1928]. The Phenomenology of Internal Time Consciousness. Translated by J. S. Churchill. Indiana University Press.

Hutchinson, George. 1995. The Harlem Renaissance in Black and White. Harvard University Press.

Jobson, Christine. 2019. “Florence Price: An Analysis of Select Art Songs with Text by Female Poets.” D.M.A. thesis, University of Miami.

Kielian-Gilbert, Marianne. 2003. “Interpreting Schenkerian Prolongation.” Music Analysis 22: 51–104.

Kramer, Jonathan D. 1988. The Time of Music. New York: Schirmer.

Levenson, Irene Montefiore. 1981. “Motivic-Harmonic Transference in the Late Works of Schubert: Chromaticism in Large and Small Spans.” Ph.D. diss., Yale University.

Lewin, David. 2006 (1986). “Music Theory, Phenomenology, and Modes of Perception.” In Studies in Music with Text, 53–108. Oxford University Press. Originally published in Music Perception 3: 327–92.

Locke, Alain. 1986 [1926]. Review of The Weary Blues, by Langston Hughes. In Critical Essays on Langston Hughes, ed. Edward J, Mullen, 44–46. Boston: G. K. Hall & Co.

Mashego, Shana. 2010. “Music from the Soul of Woman: The Influence of the African American Presbyterian and Methodist Church Traditions on the Classical Compositions of Florence Price and Dorothy Rudd Moore.” D.M.A. thesis, University of Arizona.

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. 2012 [1945]. Phenomenology of Perception. Translated by Donald A. Landes. New York: Routledge.

Moham, Carren. 1997. “The Contributions of Four African-American Women Composers to American Art Song.” D.M.A. thesis, Ohio State University.

Peebles, Sarah. 2008. “The Use of the Spiritual in the Piano Works of Two African American Women Composers – Florence B. Price and Margaret Bonds.” D.A. thesis, University of Mississippi.

Peters, Penelope. 1995. “Deep Rivers: Selected Songs of Florence Price and Margaret Bonds.” Canadian University Music Review 16: 74–95.

Price, Florence. 1941. “Songs to the Dark Virgin.” New York: G. Schirmer.

———. 2021. Four Songs from the Weary Blues. Edited by John Michael Cooper. New York: G. Schirmer.

Rampersad, Arnold. 1986. The Life of Langston Hughes, Volume 1: I, Too, Sing America. Oxford University Press.

———. 1988. The Life of Langston Hughes, Volume 2: I Dream a World. Oxford University Press.

Skansgaard, Michael. 2020. “The Virtuosity of Langston Hughes: Persona, Rhetoric, and Iconography in The Weary Blues.” Modern Language Quarterly 81: 65–94.

Schoenberg, Arnold. 2010 [1975] 1931]. “Linear Counterpoint.” In Style and Idea, 60th Anniversary Edition, ed. Leonard Stein, 289–98. Translated by Leo Black. University of California Press.

Schwarz, A. B. Christa. 2003. Gay Voices in the Harlem Renaissance. Indiana University Press.

Smith, Ayana. 2005. “Blues, Criticism, and the Signifying Trickster.” Literature and Music 24: 179–91.

Smith, Bethany. 2007. “‘Song to the Dark Virgin:’ Race and Gender in Five Art Songs of Florence B. Price.” M.M. thesis, University of Cincinnati.