It may well be asked why, after almost 30 years, questions should arise regarding the reconstruction of Bela Bartok's posthumous Viola Concerto. After all, the composition has long ago occupied its proper place among the concertos of first rank in contemporary standard repertoire. Not only has the Viola Concerto been recorded many times since the first recording in October, 1950, with William Primrose, myself conducting, and the composer's son Peter Bartok as engineer, under the label of "Bartok Records"; but even violinists such as Yehudi Menuhin temporarily changed instruments to join the legions of artists who have recorded as well as performed the composition.

Yet as the years have gone by and the concerto has gained more and more fame, reports have continued to spread that a good part, perhaps even most, of the posthumous Viola Concerto (would that it were so!) is the creation of its reconstructor. For an example, as recently as January, 1974, I was sent a review of a number of performances of the Viola Concerto with the Philadelphia Orchestra. It bears the following caption: "Disputed Bartok Concerto Given an Undisputably Fine Rendition." The review begins: "Did Bela Bartok really write the Viola Concerto credited to him? . . . Bartok scholars, such as the author of the Bartok article in the Grove's Dictionary, the musician's bible, reject the Serly version as not Bartok at all."1 The review itself, which happens to be favorable, is not our concern. But it is of great moment that light be cast on this work now in the standard repertoire for over a quarter century.

During the first years before and after the reconstruction, I remember being inundated by phone calls, letters, and requests for interviews asking for detailed information on both the Viola Concerto and the Third Piano Concerto. I should have had a secretary to assist me, but there was no one to pay the cost. Nevertheless, I gladly answered all inquiries and spent hours with almost any musician interested, describing to them what was being done, even as the grueling task was still in progress. Moreover, the original manuscript, though carefully guarded by me, was nevertheless always open for inspection to sincere musicians. As it turned out, most of them were only curiosity-motivated; what they wanted was a bird's-eye view, not the precise facts. True, I did not realize at the time that what was to me just a grueling, painstaking job appeared to most others more formidable than a Chinese crossword puzzle.2

Curiously enough, no so-called authority of note, no musicologist, historian, composer, or biographer showed the least interest in personally seeing me to examine and discuss the manuscript in detail, except one person by correspondence, Professor Halsey Stevens, whose name was unfamiliar to me at that time. As I recall it, he asked a few routine questions about the Viola Concerto, to which I replied to the best of my knowledge.

Then, almost immediately after the posthumous Viola Concerto's successful radio premiere by William Primrose and Ernest Ansermet with the NBC Symphony in January, 1950, whisperings about the authenticity of the concerto began to circulate. First came the music reviewers who raised the questions directly or inferentially. How much is Bartok's? How much is Serly's? Were any parts really completed? Which came first, the Third Piano Concerto or the Viola Concerto? What parts were finished by Bartok, and when? Ad infinitum.

But it was only sometime after the "experts"—most of them "Johnny-come-latelys" to whom I paid little attention—got busy that a lot of rumors, more fancy than fact and solely based on the printed score, began to accumulate regarding the concerto. Some of these alleged Bartok experts declared their ultimate opinions as though they had dissected the original manuscript from end to end. Though I was strongly tempted to give some kind of rebuttal to these mischievous merrymakings, I contented myself with the thought: Better to let time be the final judge.

It was, therefore, sad for me to discover that once Halsey Stevens' biography was issued in print,3 the essay written by him on Bartok's last two posthumous concertos was accepted without further inquiry as gospel, at least to the English-speaking music world. Hence, I feel it incumbent upon me, before it is too late, to explain for the first time in print, how I came to do the reconstruction and to express my own evaluation and explanation of the posthumous Viola Concerto, and a measure by measure exposé of the concerto before and after its reconstruction.

But before doing so, let me give a summary of Halsey Stevens' version. The pattern is first set early in his general assessment of Bartok's concertos (p. 228): "At this point the Viola Concerto cannot be properly evaluated, since it was completed by another hand. No matter how skillful the reconstruction, it must be admitted that no one but the composer himself could have decided exactly how it was to be done; and for that reason there will always be reluctance to accept the Viola Concerto as an authentic work of Bartok." I must interrupt this statement at once to express most emphatically that had I not been convinced that the concerto was completed according to Bartok's sketches, I would have either so stated publicly, or would not have undertaken the task of its reconstruction. And by the term reconstruction I do mean return to the original state.

Stevens continues later (pp. 253-254): "Primrose considers the Viola Concerto 'a sensitive and inspired work and a real contribution to the literature of the viola.' It would be pleasant to record that it is Bartok's crowning achievement; it is, unfortunately, nothing of the kind. Even with access to the original sketches it is impossible to draw more than tentative conclusions."

In his analysis of the concerto, naturally based on the printed score, Stevens makes short work of the first two movements: "The first movement, Moderato, is a fairly conventional sonata-form structure, throughout much of which there is little Bartokian distinction, though Bartokian devices are everywhere to be observed. . . . Certain sections are like caricatures of pages written more strikingly elsewhere. . . . Even the canonic writing, so largely entrusted with the elements of suspense and culmination in Bartok's music, becomes dry and somewhat scholastic here." I interject that of the three movements, the first is the longest and most complete.4 And of the slow movement, Stevens continues: "The second movement, an Adagio religioso, like that of the Third Piano Concerto, lacks the distinctiveness of its counterpart." Then, of all things, he juxtaposes and compares Bartok's Fifth and Sixth Quartets with the Viola Concerto: ". . . the piangendo motive of the viola and the supporting thirty-second note scales seem borrowed from the Fifth String Quartet, where they were much more effectively employed. [See my later notes on this part.] . . . The three movements of the concerto are connected by interludes. . . . Despite this device the movements appear disconnected. The signature theme of the Sixth Quartet accomplishes its purpose economically and convincingly. The interludes of the Viola Concerto, on the other hand, have no cumulative function, and their use appears arbitrary rather than purposeful." To compare the fantastic and unique "cyclic motto theme" in Bartok's Sixth Quartet with the Viola Concerto, written specifically to display the virtuoso qualities of the instrument, is an absurdity completely out of context. It is like estimating the relative balance between Brahms's Fifth Hungarian Dance and his Fourth Symphony.5 I cannot refrain from adding at this point that, in my opinion, the remarkable cyclic motto theme of the Sixth Quartet is a new and innovational structural form never used by Bartok either before or after the Sixth Quartet.

Coming to the third movement, Stevens concedes: "It is only in the Finale movement that one feels a trace of authenticity. . . . Its themes are lively and rhythmic; and here at last Serly has let the orchestra be heard." It is almost ironic that Stevens gives credit and authenticity to the only movement which, though completed to the last measure, was nevertheless rushed through, with a good part of the movement consisting merely of a single melody line. "The only serious fault," he continues, "is its extreme brevity; the four and a half minutes it occupies leave an impression of truncation.6 . . . The defects of the Viola Concerto—aside from any inadequacies that may have resulted from its completion by another hand—no doubt betray the painful circumstances of its completion." Stevens then ends his narration of the last movement with a misleading statement, based on a partial quote from notes of my last conversation with Bartok on the night of September 21, 1945: "Bartok worked on the last two concertos simultaneously, but left the Viola Concerto in sketch while he completed, save for the last few bars, the Third Piano Concerto apparently intended as a legacy for his wife. It is natural, therefore, that the latter work, upon which he lavished the last ounces of strength, should be the more convincing."7

Before presenting as closely as is possible the accurate and true story of the Viola Concerto's reconstruction, followed by my own assessment of the last two concertos, a few words must be said in review to Stevens' implications as to who did what—the composer or the reconstructor—in the Viola Concerto. Notwithstanding his low opinion of the first and second movements, I can state with unequivocal certainty that both of these movements were completed by Bartok and are his music from the first to the last measures. Ironically, the part of the concerto which Mr. Stevens claims to be the only "real" Bartok, the Finale movement, was the one most incomplete in Bartok's sketches.

Professor Stevens is, of course, fully entitled to his opinion of Bartok's posthumous Viola Concerto, but time and the facts point the other way. Now in its twenty-fifth year since the premiere performance took place in Minneapolis in 1949, it has, according to statistics recently given me, become the most frequently performed concerto ever written for the instrument. Moreover, it is used by many orchestra conductors as one of the "musts" for violists when auditioning for a position in a symphony orchestra. Therefore, a competent violist can hardly function without being familiar with the concerto. It is the first work that truly broke the barrier of prejudice most conductors had in the past against the viola as a full-fledged solo instrument. It is doubtful if there exists a professional orchestra or even a competent student ensemble in the world where it has not been performed. Now one of the popular standard concertos for any instrument, it gives promise to continue so for many more years to come.

Meantime, I think it most important, and it is my fervent desire, that sometime soon the trustees of the Bartok estate and his publishers will make available in print—or at least in reproduction—the original sketches, for all serious musicians desirous of making a minute study of this important document. In this way in due time, scrupulously careful and scholarly experts will certify that the contents of the Viola Concerto as printed are totally Bartok's music. Until such time, I feel it incumbent upon me to recount to the best of my recollection, aided by some almost-forgotten notes, my version of the reconstruction, followed by my assessment of the concerto. At the same time, I cannot close this part of my story without mentioning that the very few competent musicians who had the patience to retrace with me, step by step, the progress of the reconstruction agreed that the task which fell upon me was well-nigh an impossible one. Nevertheless, I must confess that without some inexplicable, intuitive grasp into the inner mind of the departed composer—call it E.S.P., though I have no belief in such practice—I would have given up. However that may be, I did virtually live for over two years day and night with those thirteen mottled pages. So in a sense it could be considered a sort of re-incarnation of a work lost. Therefore, the reconstruction of the Viola Concerto has no parallel in history to any of the past known situations of posthumously-completed works such as, for example, Süssmayr and Mozart's Requiem. For mine was a task of completing a major work already concluded, if one can use such a paradoxical expression.

Now, to rectify the question of the "cello version," referred to as follows in Steven's biography (p. 253): "Although it had been commissioned by William Primrose, because of 'apparently insurmountable difficulties' with the Bartok estate he had given up hope of receiving it when, in January, 1949, Ernest Ansermet told him that the Concerto was being rewritten for violoncello."

But the facts behind the rumor of a cello version of the Viola Concerto are more involved than this brief statement implies. After I had examined the manuscript thoroughly (October, 1945 and into 1946), it occurred to me that, in view of Bartok's statement to Primrose, "Most probably some passages will prove uncomfortable or unplayable" (and indeed there were such), and remembering Bartok's setting of his own Rhapsody No. 1 for both violin and cello (1928), I decided from the start that I would work on a double version, one for viola and another for violoncello. And so, when both versions were simultaneously completed in the fall of 1948, I immediately arranged for a violist and cellist among my friends to learn the concerto. The two fine young artists who volunteered turned out to be Burton Fisch, violist, and David Soyer, cellist, with the excellent pianist, the late Lucy Brown, providing the reduced orchestra accompaniment. An evening was arranged at my New York studio to which sixteen relatives, friends, admirers, and musicians, all of whom were close to Bartok, were invited to listen and give their views. They were requested to jot down on a piece of paper which version they favored, the viola or cello. If my memory serves me well, surprisingly the vote was eight to six in favor of the cello version, and two did not wish to commit themselves. In any case, though this may now seem paradoxical the cello received the slightly higher vote. Nevertheless, it was later rightly decided that the original agreement with William Primrose be honored.

Subsequently Primrose and I got together. After many sessions spent ironing out technical details, for which we all must be grateful to him, the premiere was arranged and took place with the Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra in December of 1949; and, shortly after, the radio broadcast took place with the NBC Symphony. But previous to the premiere performances, another delicate question had come up between the Bartok Estate, Boosey and Hawkes, and myself. This was the problem of how the publication should be inscribed. Was the printed score to read: "Reconstructed by Tibor Serly"?, "Arranged by—"?, "In collaboration with—"?, "Posthumously Completed by—"?, etc. It is well known that an arrangement of another composer's work commonly receives equal credits such as: Bach-Stokowski, Moussorgsky-Ravel, etc. In this instance no name recognition is allotted except in program notes, and radio performances simply list Viola Concerto—Bartok. Be that as it may, after a number of conferences I was persuaded to accept the phrase, "Prepared for publication by Tibor Serly."

But for me it was a labor of love and admiration for the man that impelled me to take on this formidable task, which took almost three years of my time during which my own work lay fallow. Thus the circumstances remain as one of the most enigmatic questions ever posed for resolution. For there is no precedent in the history of music where one composer had to put his mind, body, and soul, as it were, into another composer's being. Small wonder that within a short time, even as the Concerto was gaining more favor and popularity, misconceptions and provoking innuendos became rampant. These, then, were the auspices under which Bartok's Posthumous Viola Concerto was presented a quarter of a century ago to the music world.

II

A MEASURE BY MEASURE EXPOSITION OF THE RECONSTRUCTION OF BELA BARTOK'S VIOLA CONCERTO

First Movement

From the beginning of the first movement, m. 1 to m. 1688 (slightly more than two-thirds of the longest movement in the concerto), every note including the melodic, harmonic, and contrapuntal parts was completed by Bartok, with the exception of two separate measures. M. 73 (Ex. 1) is a repetition of m. 74, an octave lower.

Ex. 1

This extension was added to provide more brilliance in the viola's climb to the high G-sharp. Bartok's manuscript indicates some indecision here. And m. 143 (Ex. 2) is a partial repeat of m. 142.

Ex. 2

Both William Primrose and I felt the necessity of an extra measure of timing to resolve into the tranquil re-entrance of the orchestra after the long viola cadenza. M. 168 to m. 184—with one different measure, the 4/4 m. 172 added by Bartok—are obviously the recapitulation (slightly modified) of m. 48 to m. 60. This includes the reprise of the orchestra tutti, now a fifth lower, in conformity with the classical tonic and dominant relationship. The contrapuntal voices, however, had not been put in, and the reprise of the tutti, m. 175 to m. 183, though clearly implied, had to be orchestrally filled in. True, the second time Bartok might have altered this tutti more than I dared to chance. But an essential goal in the reconstruction of the entire concerto was to avoid, if possible, any original music of mine. Happily, except for a few repeated or modified repeat measures, this turned out to be unnecessary in any of the three movements. So, for example, the sixteenth-note figure ending the recapitulation of the tutti was extended from seven to nine measures, in order to slacken the speed (see mm. 182-183), but the figure remains precisely the same. Mm. 185-186 were empty except for the viola melody and a whole-note "A" in the lower staff. Therefore, m. 184 (Ex. 3) was added to enable the unobtrusive return to the now more poignantly varied reprise of the second theme, which is also more elaborately worked out by Bartok than before.

Ex. 3

From m. 185 to m. 220, all is exactly as written by Bartok. It is interesting to note that, despite the ultra-chromatic guise of the second theme recapitulation, the only time in the entire concerto the orchestral background progresses downwards through the complete chromatic scale is starting on E-flat, m. 197, and ending on the low E-flat at m. 200.

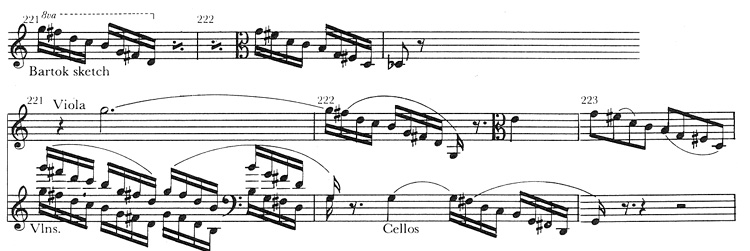

The most daring adjustment was made near the end of the movement. M. 221 and m. 222, originally written for viola solo alone in Bartok's sketch, were converted into a combined orchestra and viola passage and extended one more measure to m. 223 (Ex. 4).

Ex. 4

On this my judgment may be faulted, but the original figure for solo viola seemed to me abrupt and uncertain. Again, however, there are no changes in the actual notes in the passage. The extra measure was slowed down from sixteenth to eighth notes (m. 223), which leads into the three-measure tutti on muted trumpets and strings. Four more measures on the solo viola accompanied by the woodwind chord above brings the movement to a close on a pure C-major triad.

Reviewing the first movement, all told only four measures in four different places were subjoined (74, 143, 184, 223). Thus, of the 230 measures which complete the first—and longest—movement (excluding the nine repeated tutti measures), 226 measures are Bartok's; 4 are mine. This can hardly be called an unfinished or incomplete movement. I think it most essential to bear in mind that not one single bar of Bartok's was omitted.

The Questionable Interlude—so called—Preceding the Second Movement

The Lento (Parlando) which follows immediately after the initial movement is a brief, lugubrious but powerful "Interlude" of fourteen measures. Still based partly on the main theme in the first movement, this passage ends with a brilliant, rapid chromatic-scale cadenza coming to a halt on the viola's open C-string. At this point there is a bar line marked 2/4 (in Bartok's sketch), followed by a blank space which also terminates page seven in the original manuscript. This corresponds to the low C one bar before the four-measure introduction to the second movement proper in the printed reduced score. For me to have omitted these forceful fourteen measures from the concerto, reproduced precisely as written by Bartok, would have been unthinkable.9 But the decision to include these measures caused the most vexing problem in the concerto, as it involved all three movements. I should mention at this point that it may have been my description of this vexatious enigma which could have created the false rumor that Bartok intended to add a fourth movement to the concerto. In any case, the second movement proper, which follows immediately (p. 8 in the manuscript) contradicts any thought of the Interlude part being intended as an independent movement. (More on this later.)

Second Movement (Adagio Religioso)

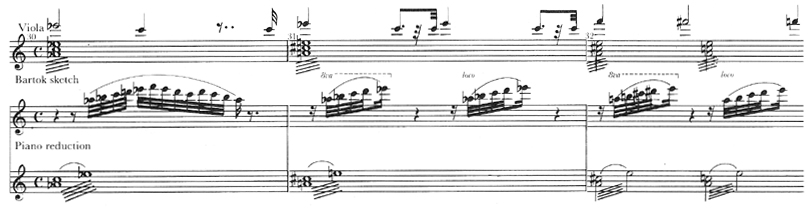

The Adagio commences on an E-major chord (p. 32 in the printed score) without any indication of an introduction apparent. Otherwise, the entire movement is complete in both the viola solo and the orchestra background from beginning to the end of its 57 measures. In fact, until m. 30 not a single fill-in of any sort was necessary. From there on, for the next nine measures (m. 30 through m. 38), Bartok's sketch of the accompaniment to the melody in the viola consists simply of a descending sequence series of consonant triads. These are replenished with orchestral embellishments of my own invention, which were to me remindful of the "out-of-doors" mood in the trio part of the slow movement in the Third Piano Concerto, written at the same time (Ex. 5).10

Ex. 5

But not one note of the basic harmony is altered, only the orchestration lightly filled in. At m. 40 a curtailed reprise of the beginning Adagio motive connects into an echo-like recall of the main theme of the first movement (m. 50). From there, the movement accelerates gradually into the brief but brilliant cadenza which leads with stunning impact directly into the introductory Allegretto part. Thus the entire slow movement, including the bridge connecting into the introduction to the last movement, is set down complete and exactly as Bartok wrote it.

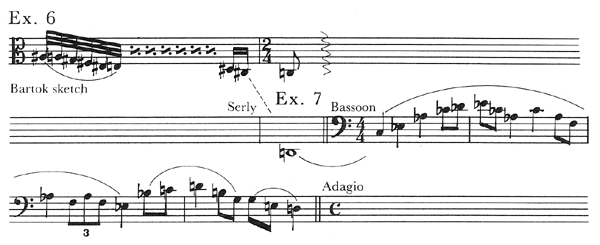

We return now to the enigmatic bar line at the end of the "Interlude," which corresponds to the viola's low C five measures before the second movement (Ex. 6, p. 31 in the printed score).

Ex. 6 // Ex. 7

The two-fold question arises: (1) Did Bartok intend to omit the "Interlude" portion between the first and second movements? If so, it seemed strangely unlike him to have commenced the 2nd movement on a bare E-major triad. (2) Contrariwise, if Bartok wanted to retain the "Interlude," did he intend to proceed at once to the 2/4 Allegretto introduction to the Finale? But then there would have been no place at all for the 2nd movement proper to be established. Perhaps Bartok had some simple solution in mind. If so, in this one place it escaped me. Therefore, I was obliged to use the prerogative of the composer in order to preserve the interlude verbatim. I decided to insert a connecting part which would lead smoothly into the 2nd movement. But the question was how to do so without upsetting the balance. After much searching, I decided to borrow the melody line at m. 154 to m. 157 from the first movement in the orchestral interlude but to transfer it to the solo bassoon and omit all accompaniment.11 The shift to a third above at m. 157 allows the bassoon to gently modulate into the second movement proper (Ex. 7). Thus, by the simple process of adding four unison measures borrowed from a previous passage, I solved what was to me the knottiest problem in the concerto—and this without a single bar of Bartok's music having been omitted from the original manuscript, either in the first or second movements, including "Interlude."

The Enigmatic Introduction to the Third Movement

With the above dilemma solved, the one unsolvable riddle occurs between the "Allegretto Introduction" and the third movement proper. It is the only place in the concerto where I found it unavoidable to omit eight measures. To attempt to give the details of these left-out measures cannot be done without a minute analysis of the original manuscript (pp. 8 and 9) before and after the eight mysteriously unaccountable measures. Suffice it to say that countless attempts were made but each clue led nowhere. And since the rest of the twenty-five bars of introduction led perfectly into the Allegro Vivace finale, there was no alternative but to omit these measures. This is just a guess on my part, but it is my conviction that Bartok himself would not have included the bit.12

Third Movement, Allegro Vivace

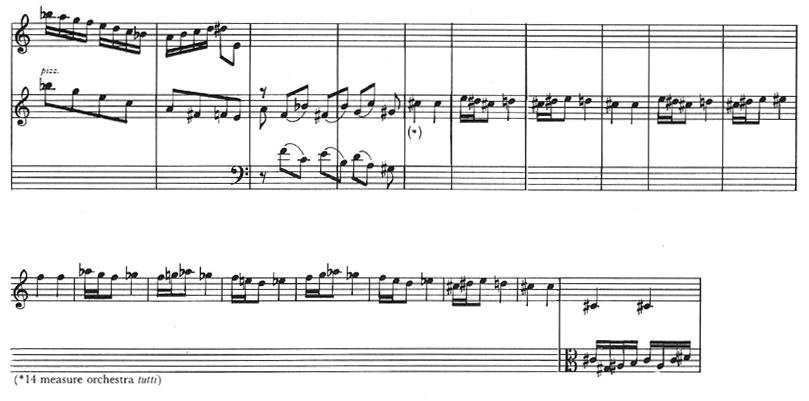

It must be conceded at the start that the last movement proved to be the most bafflingly arduous. This is not due to its incompleteness, as it was finished to the very last measure, but rather on account of its bareness. The two previous movements were in comparison harmonically, melodically, and contrapuntally complete in the sketches. Apart from deciphering the many strange signs and symbols and trying to locate partially-written measures sometimes hidden elsewhere, the main task was in the orchestration which, as stated in the printed score, is entirely mine. In the third movement the problem was quite different. Frequently there was only a single melody line to go by, with a few chordal or contrapuntal indications at intervals. Hence, from m. 5 to m. 80 (except here and there a bar or two of a counter melody), the manuscript consists solely of the melody line (Ex. 8).

Ex. 8

This includes fourteen measures (51 to 64), which I deduced to be the first orchestra tutti (Ex. 9).

Ex. 9

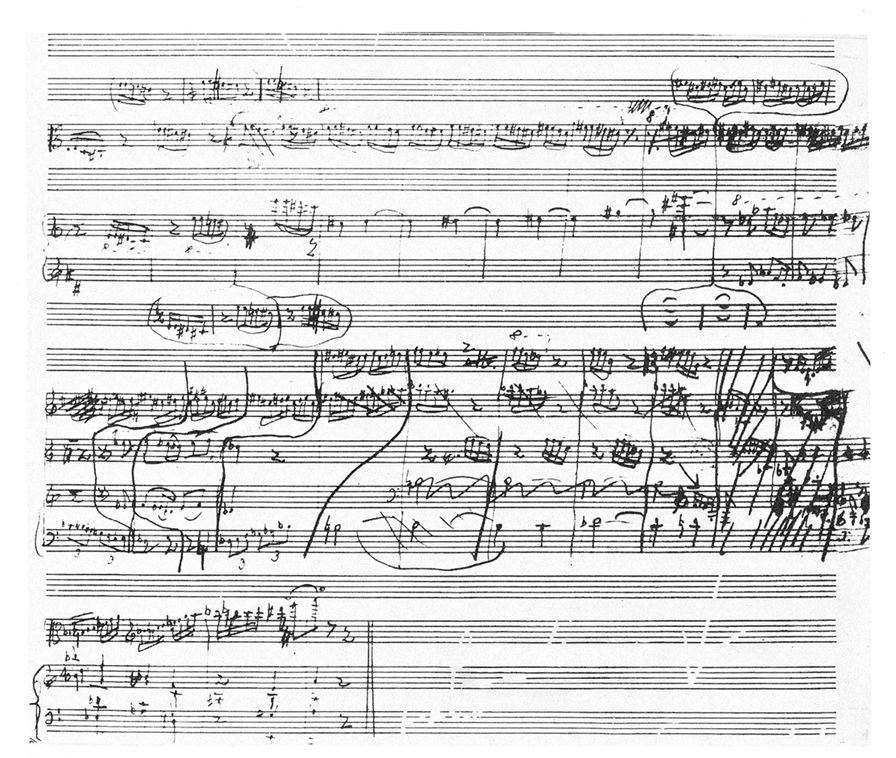

This tutti passage had to be fully orchestrated and harmonically filled in. However, from m. 80 to m. 114 the basic harmony and contrapuntal parts to the solo viola—written on two, sometimes three staves—are followed exactly as noted by Bartok. So too, from m. 114 to m. 230 everything is as set down in Bartok's sketches, with the exception of nine measures which were added by me. For these nine measures (197 to 205), I accept full responsibility, for this reason: after the sparkling and ingeniously contrapuntal, though classically lucid orchestral climax at m. 150 to m. 177, it seemed to me that some sort of a very virtuoso-like passage was needed on the solo viola. This is indicated by Bartok, but was not in my estimation quite fulfilled. The nine-measure extension afforded me the opportunity to utilize the total range of the viola with utmost brilliance. However, I should again point out that this was accomplished by simply repeating m. 206 to m. 211 a fifth higher and extended from six to nine measures. As I recall it, Mr. Primrose, too, suggested some technical improvements on this score. Nevertheless, from m. 81 to m. 230 (which includes the added nine measures) everything is realized in Bartok's original sketches written, for the most part on two, sometimes three, staves. The final measures (230 to 258) were quite a different situation. Here the lower half of the final page (p. 13) in the manuscript is a mass of hastily scribbled and blearied sketches, notated mostly on four, occasionally five, overlapping and confusedly zigzagged staves. Yet, strangely enough, the "last four bars"—perhaps not so surprising considering the circumstances—are as transparent as are the opening measures of the first movement.

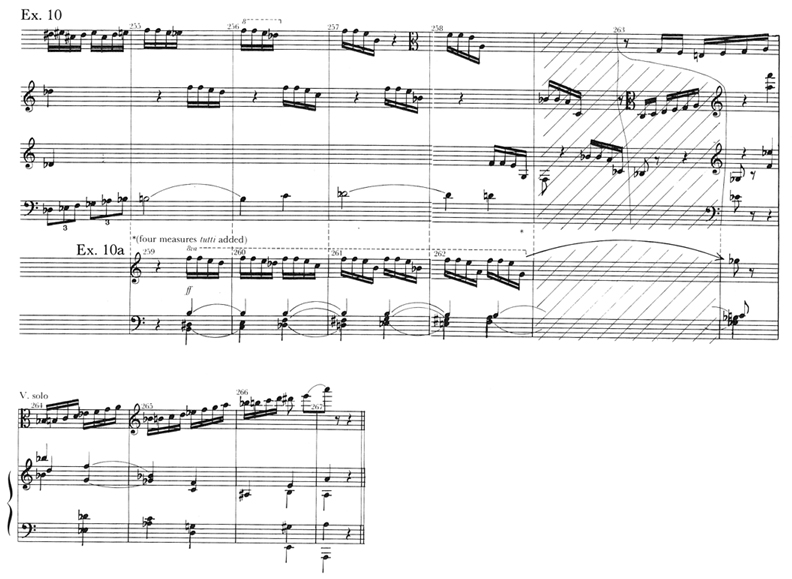

Before closing this exposé of how and what was done in the reconstruction of the concerto, I have one more transgression to confess. The five closing measures of the finale, with their four different tonal resolutions, emerge with such a shocking abruptness that I could not resist interjecting a short tutti of four measures, preceding the low entrance of the viola. Hence bars 255 to 258 were repeated fortissimo for full orchestra with my own harmonization (Ex. 10-10a).13 For this I hope I may be forgiven, although I ponder what the reaction would now be, were these four measures to be omitted.

Ex. 10 // Ex. 10a

Thus, without intent to over-dramatize this final portion of Bartok's posthumous Viola Concerto, here truly, the manuscript indicated to me beyond question Bartok's desperate effort to get on with the end. One needs only to glance through the lower half of the manuscript's final page (p. 13) to note the feverish urge that seemed to drive Bartok ineluctably on to the successful completion of the last five bars.

The last page of Bartok's manuscript, showing Ex. 10-10a.

By Permission of Boosey and Hawkes, Ltd.

III

Now as to my own views about Bela Bartok's four last works, written in the U.S.A. between the years 1943 and September 21, 1945. At the risk of being accused of dogmatism, which I willingly accept, it is my firm conviction that in Bela Bartok the world of music was blessed with a creative genius born but once in a century or two. Perhaps like only Bach and Mozart before him, Bartok was incapable of accepting anything less than perfection in all of his mature works. It is, therefore, a misconception to refer to his last works, finished or unfinished, as a compromise or weakness due to the ravages of illness. In paralleling Bartok with the two former giants, however, there is this difference: they did not live in an age of the musical problems—not to say social and economic—which beset the music world at the end of the nineteenth century, when everything seemed to have gone awry.

Thus, in an age when music as previously understood was falling apart, and "isms" and "schisms" were the order of the day, Bartok alone maintained a dogged conviction even throughout his most dissonant periods, that established structural forms and the basic tonal order, which took centuries to evolve, were not to be wantonly discarded. Moreover, Bartok's works include, besides music, his scientific folklore researches and anthropological work.14 But above all else, his life centered on his creative musical output. In this he demanded perfection structurally, architecturally, mathematically, and creatively. Although, like a number of his contemporaries, he naturally went through experimental periods from one extreme to another, unlike most of the others, Bartok's transitions are not to be mistaken for eclecticism. On the contrary, these changes were always accomplished deliberately and with full comprehension. It is for these reasons Bartok's works are generally separated into three distinct epochs. As tempting as it is, this is not the proper place to dwell on all three of the various aspects of his development. The purpose here is to point out what I believe was the beginning of his fourth and most mature period, which would have been—if premature death had not snuffed out his life15—the ultimate epoch in which all doubts would vanish as to how and in what direction future music could go, after the fumblings of the first half-century. It is, therefore, my assured belief that the last four works of Bartok's American years may turn out to be prophetic. That he did not live to achieve his goal completely makes them all the more vital, as the message contained therein throws wide open the future of the twelve semi-tones to composers.

As our main concern is with the posthumous Viola Concerto, most of this last part will be so confined, with only passing reference to the three other last major works. As previously mentioned, it has been erroneously stated by those who can only see with myopic musical lenses, or through ignorance, that Bartok had compromised—had softened—in the last years of the Concerto for Orchestra, the Solo Sonata for Violin, the Third Piano Concerto, and finally the Viola Concerto, left in sketches. Far from having compromised, it is my conviction that his last works stand as a proclamation to his faith and belief that classical purity can be eventually achieved in the most extreme dissonant and sophisticated style.

Bartok was never a preacher, as were many of his contemporaries, but a doer. By this I mean his message has always been in his creative output. Thus the last four works, and particularly the final two posthumous concertos, although having on the surface a traditional facade, far from being a backward glance, point straight to the future. For compromise was a word unknown in Bartok's life's vocabulary.

Bartok's Viola Concerto is based on a single chord, the dominant seventh (V7 chord), the most disdained structure in contemporary music; but the sounds are different. For those who really knew Bartok, no more convincing substantiation could be presented to better illustrate that he was on the track of some new alignment in the chromatic scale. Thus it is my personal view that nothing less than masterworks could have issued from the pen of this overwhelming creative genius in his last years. If he felt that he had nothing more important to say, he simply would not write, as indeed he did not, from 1940 to 1943.

Therefore, to me it is as pointless to debate whether any one or other of his last four works—in their different ways—are lesser or greater as to debate the qualitative differences in Mozart's last three symphonies. We are not discussing the medium for which they were written, only the music. Consequently, even if the last two concertos had remained as unfinished items, which of course is not the case, they would be of utmost significance to music history and the art of composition. Hence even though it was written out on but thirteen tight pages of sketches, once I was fortunate enough to decipher it in its totality, to me the Viola Concerto was as complete (except for the orchestration) as was the Third Piano Concerto. This, then, was my reason for tenaciously staying with the job (though often discouraged) until it was successfully consummated. Therefore, I can say with justified pride that statistics have borne out its constantly growing popularity after a quarter century since the premiere performance in Minneapolis on December 2, 1949.

1James Felton, The Philadelphia Evening Bulletin, Jan. 19, 1974.

2William Primrose commented: "I saw the manuscript shortly after Bartok's death at Mr. Serly's apartment in New York. I was appalled; I didn't know how he could make anything out of it . . . the manuscript was a type of jig-saw puzzle." David Dalton, Genesis and Synthesis of the Bartok Viola Concerto, Diss., Indiana University (1970), p. 29.

3The Life and Music of Bela Bartok (New York, 1953; rev. 1964).

410:20 minutes by Bartok's own timing.

5I am reminded of Bartok's comment when he read the last part of a review of the premiere performance of his Violin Concerto with the New York Philharmonic Orchestra (1943), which ended: "It will never replace either the Beethoven or the Brahms Violin Concertos." To this Bartok commented: "Who ever heard of any composer writing a concerto to replace another composer's?"

6Bartok's own timing of the last movement, precisely marked by him (top of manuscript, p. 7) is four minutes and forty-five seconds. Hence, this precludes that any part of the movement was truncated by me, or in Bartok's estimation.

7According to his wife, Bartok kept switching from the Viola Concerto to the Piano Concerto and vice-versa. Hence, he could not have just lavished his "last ounce of strength" on the latter. While it is true he devoted his last few hours to the final measures of the Piano Concerto which had been completed in the sketch and fully orchestrated, minus the last seventeen bars, it was the Viola Concerto he had previously completed to the very last bar. He had merely set it aside as no longer a problem—as stated in his letter to William Primrose—in order to make sure his legacy to his wife Ditta would be fulfilled. Bartok, noted for never saying less than the absolute truth, confirmed this in his letter to William Primrose. The letter is printed in the pocket score (Boosey and Hawkes, 1950).

8All bar numberings relate to the printed Pocket Score. By permission of Boosey & Hawkes, Ltd.

9Even a brief glance at the original manuscript confirms that there is no relationship to the "motto" theme of the 6th Quartet.

10Here is the one place Halsey Stevens came close alluding to the "out-of-doors" idea. It so happens, aside from the Third Piano Concerto, I had in mind several similar passages, such as in "Musique Nocturnes" (from Out-of-Doors Suite), "Minor Seconds" (Mikrokosmos). I could cite others, but these will suffice. At that, I should feel complimented that my planned likeness at least received recognition. I might add also that the embellishments used were modestly scored deliberately, so as not to interfere with the purity of the melody line.

11In the first statement, this passage is played on the oboe.

12I should mention that there were odd motive bits elsewhere jotted down. Some were used; others, not. But in most instances the indications were clear.

13May I say regarding these slight encroachments—if such they be—that in my Mikrokosmos Suite transcription for large orchestra, done when Bartok was still alive (1942), several repetitions of passages and extensions were added by me in the orchestra version with his full sanction, Let us also recall Bartok's letter to Primrose about certain adjustments he was prepared to make. (See letter to Primrose in printed score.)

14It is said by anthropological scholars that Bartok would be considered a genius for his scientific contributions to folklore alone.

15"It seems I must leave just as my trunk is so full—"Bartok.