In Musical Form and Musical Performance, Edward T. Cone states that "artistic quality is intentionally produced esthetic quality"; the so-called intentional fallacy is "no fallacyunless it is the fallacy of believing that there is an intentional fallacy."1 The issue is important, and Cone has returned to it in several contexts.

In "The Authority of Music Criticism," Cone argues that a critic who evaluates a composition "must try to distinguish the composer's work from the interpreter's."2 The "interpreter" is not only the performer, but also the critic. One "can know a piece of music only through its performance, real or imagined" (p. 109); only subsequently can one try to distinguish the composer's contribution from the interpretive additions. And with the greatest works, the composer's full conception is certain to remain elusive: "Every great work of art eventually demonstrates the inadequacy of even the best critic. . . . The greater the work, the more partial must be any single interpretation and the more inevitable its eventual supersession." (p. 111) Nonetheless, "judicial criticism. . . must be informed by a faith in the conception of the composition as a standard that can be ascertained and that should be respected." (p. 109) Mention of "faith" implies an analogy between the composer's conception and the will of God. The basis of the analogy is easily specified. A religious believer has faith in the will of God as the standard of good and evil; though God's will is always to some extent unknown, the believer must learn as much as possible about this standard and act accordingly.

The theological analogy extends further. Defending the centrality of the composer's conception, Cone presents a "pragmatic" argument that "somewhat resembles certain apologies for religious commitment." The resemblance is more than formal, for Cone's argument has moral aspects: "Only by assuming the existence and the accessibility of a standard against which interpretations of a composition must be measured can we prevent performances from degenerating into displays of personal self-indulgence and critiques from becoming mere exercises in autobiography." (pp. 106-7) Mere facts do not force an interpreter to recognize the composer's conception as the basis of interpretation; but the interpreter may decide to assume the availability of a standard by considering the effects of its adoption.

One effect of such an assumption, according to Cone, is prevention of the self-centered activities that would ensue in the absence of standards. But it would be wrong to over-emphasize Cone's moralism. "Personal self-indulgence" and "mere autobiography" might reflect selfishness; but they could also be a form of isolation. Respect for the composer's conception may resemble respect for God's authority, but the aspiration to share the composer's awareness is also a desire for contact with another person. The model of interpersonal communication is prominent in another Cone essay, "Schubert's Promissory Note," which moves from technical analysis of a single composition to a discussion of Schubert's personal experience: Cone suggests, tentatively, that several of Schubert's pieces may reflect the "desolation" and "dread" induced by his incurable syphilis.3 The treatment of the biographical material is ambiguous. Cone states that the composition under discussion determines a broad "expressive potential" having to do with "the injection of a strange, unsettling element into an otherwise peaceful situation"; it might seem that the connotations for Schubert of this scenario make no privileged contribution to the meaning of the work. (p. 239) But the article moves from a determination of "expressive potential" to a suggestion of the "personal experiences" that "Schubert might have considered relevant to the expressive significance of his own composition." (p. 240) The trajectory creates a sense of the biographical interpretation as a goal; the article seems to present the point of contact with Schubert's personal pain as the point at which the meaning of the music is most fully revealed, despite Cone's indications to the contrary.

In light of Cone's reiterated concern for the composer's intentions, conceptions, and experiences, someone who has not read The Composer's Voice might misunderstand the title of the book. But "the composer's voice," as readers learn, is not simply the voice of the actual historical composer; it is the voice of a persona, the voice that issues from a mask. Not only is there a gap between the composer and "the composer's voice," but also (more obviously) the "voice" is not really a voice. The difficult concept named in the title encapsulates much of the difficulty of Cone's book. In approaching the concept a detour outside music criticism will be helpful.

Literary theorists write about the "voices" of poetry and narrative. Wimsatt and Beardsley, in "The Intentional Fallacy," state that the words of a poem issue from a dramatic character; they invoke the fictional speaker in order to direct the interpreter's attention away from the author's intentions.4 Their claims might suggest incompatibility between Cone's account of the musical persona and his insistence on the centrality of the composer's intentions; but the notion of a persona or dramatic speaker has also figured in intentionalist theories of literary interpretation. Wayne Booth, in The Rhetoric of Fiction, while maintaining a distinction between the author and the fictional persona or narrator, argues for the importance of clear communication of the author's own ideas. In Huckleberry Finn, for example, the words one reads are to be understood as issuing from Huck Finn, a fictional character; but by creating the character, Samuel Clemens is able to communicate his own views, which may differ from those of Huck Finn.5

Perhaps the persona of a musical work, somewhat like Huck Finn, is a fictional character by means of which the composer communicates with the audience. To grasp the composer's intention a listener must understand the composer's conception of the persona, and such understanding includes the recognition that the composer and the persona are distinct. This seems to reconcile the concept of a musical persona with Cone's intentionalism.6 But Cone's position is not quite so simple; one way to show its complexity is to draw on further material from literary theory.

Wimsatt and Beardsley attack the "intentional fallacy" in order to focus attention on the capacity of literature to communicate autonomously, without the aid of supplementary information about "an intention that did not become effective" in the work itself. (p. 4) But Booth, by introducing the notion of an implied author, also recognizes an important quality of autonomy in literary works. Each work carries a sense of the qualities of the person that could have written it. To discover the characteristics of this implied author, one reads the work; there is no substitute for the reading, since the implied author of a given work may reveal traits for which there is no other evidence in the biography of the author.7

Booth's implied author is not the persona or narrator. When a work employs a clearly defined fictional character as a narrator, as in Huckleberry Finn, there is also an implied author, distinct from the narrator. Even when the narrator does not figure as a character in the plot of the novel, one can distinguish between a story-teller or scribe, who writes as though recounting facts, and the implied author, who recognizes the events as fictional. The implied author is also distinct, in a certain sense, from the person who wrote the book. The implied author is a "second self" that the author fabricates for one particular text. (p. 73)

Drawing on Booth, one might try to expand Cone's account by introducing an implied composer along with the persona. But, in fact, it is not clear that this expansion is possible; Cone's musical persona may already occupy the position of an implied composer. Cone's views are hard to interpret. He writes that "one principle is clear: the persona is always to be distinguished from the composer." (The Composer's Voice, p. 84) Discussing the introduction to the last movement of the Hammerklavier, he denies that the passage places the listener in "the presence of Beethoven at work": that view reveals "a confusion between composer and persona." (p. 130) But, on the other hand, the complete persona strives for "form," (p. 26) and no doubt its ideas on form will resemble those of the composer very closely. The persona, like an implied composer, is "an intelligence embracing and controlling all the elements of musical thought that comprise a work." (p. 109)8 Since the persona takes on the tasks of a composer, it is not surprising that Cone's theological analogies in The Composer's Voice liken the persona, rather than the composer, to God or, more precisely, to God the creator: "The song as a whole is the utterance—the creation—of the complete musical persona. Like the Father, this persona 'begets' in the vocal persona a Son that embodies its Word; and it produces in the accompaniment a 'Holy Spirit' that speaks to us directly, without the mediation of the Word." (p. 18)9

So the title of the book may reflect the tendency of the persona to drift toward identity with an implied composer. Other ambiguities support this reading. Summarizing the composer's use of poetry, Cone offers a contrast: "In the poem, it is the poet who speaks, albeit in the voice of a persona. In the song, it is the composer who speaks, in part through the words of the poet." (p. 19) One can supply the omitted reference to the composer's persona, but the language implies direct contact with the composer. Cone argues that full participation in a composition involves identification: "To listen to music is to yield our inner voice to the composer's domination. Or better: it is to make the composer's voice our own." (p. 157) In interpreting this formulation, a reader may remember Cone's view that the listener identifies with the persona, not the composer. But Cone's language hardly emphasizes the distinction; these sentences invite the thought of direct interaction and identification with the composer.10 Again, in discussing the various roles that figure in instrumental music, Cone writes that "in the last analysis all roles are aspects of one controlling persona, which is in turn the projection of one creative human consciousness—that of the composer." (p. 114) Perhaps the notion of "projection" is more suggestive of the activity of "projecting" a "second self," an implied composer, than of creating a wholly fictional character; in any case, Cone's language leaves both interpretations open. The discussion of identification includes the following claim: "Even though one may identify oneself ultimately with the entire persona, that identification necessarily depends on imaginative participation in the musical life of each of its chief components—just as in reading a novel, to understand the author's point of view one may have to enter the minds of all its principal characters." (p. 122) The analogy likens the complete musical persona to the author of a novel, rather than to a fictional voice.11

Passages in which the persona seems to merge with the composer have a strange, somewhat obscure pathos. The notion of the complete persona contributes, in any case, to an assimilation of musical experience to personal relations, totalizing the composition into a quasi-human object of attention. The smaller the gap between the implied composer and the persona, the more the listener's experience tends to become, literally, communication and identification with the composer. But the identification of the persona and composer occurs only inexplicitly and inconsistently; hence the obscurity.

"To listen to music is to yield our inner voice to the composer's domination. Or better: it is to make the composer's voice our own." These words end the next-to-last chapter of the book. In a way they end the book; the last chapter is an "Epilogue" in which Cone argues, without referring to the composer or the persona, that musical events symbolize gestures, and that a composition presents a structure of "musical gestures and their patterns." (p. 169) To hear music as meaningful, a listener associates the structure of a composition with personal experience. Listening is a kind of controlled autobiographical contemplation, a pondering of the correspondence between one's own concrete experience and abstract musical patterns. In itself, music is structure; but a listener will always introduce a context, and therefore the experience of music can probably never be an experience of sheer structure.

Musicians should admire Cone's clarity and insight in discussing such difficult and controversial topics. But in the context of the book, the most striking fact about the "Epilogue" is its break with the concerns and vocabulary of the preceding chapters. The disjunction is particularly clear, and unsettling, at the beginning of the "Epilogue," where Cone indicates that a reader may reject the discussion in "the foregoing pages" as untrustworthy: the objection would be that the account merely "develops an elaborate figure of speech." Cone grants that the argument has proceeded "by metaphor and analogy," but suggests that such procedures are inevitable in describing music. Figurative language, he observes, is not deductive argument, but it can still be persuasive. (p. 158)

A reader might be more uneasy than Cone himself after this diagnosis of figurative language. It may be that tropes are more persuasive before being clearly recognized as tropes. Awareness that the vehicle of persuasion is figurative language could even raise doubts about the determinacy of the content one might be persuaded to endorse. Further, Cone does not specify which parts of the argument have been metaphorical; this is disorienting, since a reader cannot tell which parts, if any, should be understood literally. But probably figuration is ubiquitous in a study that "has developed the picture of music as a form of utterance." (pp. 159-60) In its immediate context, the recognition of figurative language follows harshly upon the description of identification. Suddenly it seems that the impression of hearing the composer's voice and of making it one's own arises from metaphor, specifically from prosopopoeia, the trope of attributing a face or voice.12 To "hear" the composer's "voice" is only to hear one's own figurative language. The implication that the illusory presence of the composer's voice is an effect of language forms a dark counterpart to the claim, in "The Authority of Music Criticism," that the accessibility of the composer's conception must be assumed by an act of faith. More generally, in the interpretive progression from sounds, to gestures, to persona, to composer, each step increases the resemblance between musical experience and interpersonal contact, but each step carries a risk that the gain in apparent human contact is the result of an arbitrary imposition, an invention rather than a cognition.

For the most part, Cone scrupulously acknowledges these interpretive posits (although, if I have read him correctly, he crosses the boundary between persona and composer inexplicitly). Cone tends to emphasize the productivity of such assumptions for interpretation. But, without moving outside the basic framework of Cone's ideas, one could take a somewhat different attitude toward these acts of positing. Musical experience is a matter of continuous temptation, in which opportunities for leaps of faith, biographically-oriented conjectures, and figurative language present themselves almost irresistibly. The temptations should be acknowledged but also, to some extent, resisted. To indicate one pattern of temptation, I want to explore the interpretive move from musical gesture to the unity of a persona, in connection with two musical examples.13

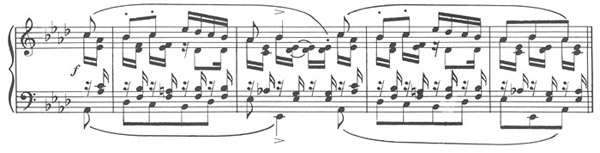

The first example is a pair of phrases from Schumann's Blumenstück. (ex. 1)

Example 1: Schumann, Blumenstück, op. 19, mm. 23-26

Though in one sense this passage, like any instrumental music, is just an array of sounds, it is easy to hear two gestures in these phrases, with the second gesture responding to the incompleteness of the first. If one asks whose gestures these are, various answers are possible. Cone writes of solo piano works in terms of a single persona, but also observes that the pianistic persona may subdivide into a range of interacting agents. (The Composer's Voice, 98-99) In the Schumann passage, the outer parts invite identification as a pair of agents, cooperating in many respects but distinguished by register and by an inclination toward contrary motion. The chords in the middle of the textures are puzzling; perhaps four dramatic characters cooperate to produce the chords (and one would have to say something about the chords with three pitches), or perhaps a single chord-producing agent occupies the middle register. Or, since the chords seem dependent on the more decisive outer parts, one might describe them somehow without invoking additional characters beyond the outer-part agents. For that matter, the coordination of the outer parts might suggest a single agent, capable of producing more than one pitch.

Cone considers such issues about musical texture, but he approaches the puzzles in order to solve them, or to recommend that the performer project a solution: "The performer on a keyboard instrument, especially, is responsible for many implied roles. An important part of his job is to decide just what, in every passage of a composition, constitutes such an implicit agent. This category should not be narrowly interpreted as including only leading components. Every note of the piece, like every instrument of the orchestra, must help define some agent, permanent or temporary." (p. 99) I suggest, however, that musical textures usually invite several discrepant individuations of agents without resolving the issue, and that the play of different individuations is an important part of musical experience. And indeterminacy of agency extends beyond texture: a listener can wonder whether the second of these Schumann phrases arises from the same agency as the first, or entertain the possibility that the  s in the melody are the intrusive self-assertions of a pitch-character.

s in the melody are the intrusive self-assertions of a pitch-character.

The indeterminacy is pervasive in instrumental music.14 One might try to reduce it by privileging interpretations that unify the events of the piece as the actions of a single agent, or perceptions of a single subject. But this unification can easily feel like just one more possible scheme of individuation, in many cases not the most obvious scheme. The persona is always likely to dissolve into a play of indeterminate agency. The prosopopoeia that unifies musical gestures into the utterance of a single voice serves as a defense against this disintegration, introducing a human presence that functions as a surrogate for the composer and an intelligible object of identification for the listener. To the extent that this unification seems arbitrary, it may take on the aspect of a purely linguistic manoeuvre, a sheer trope. The fragility or evanescence of the persona-effect need not eliminate the sense of communication with a composer or an implied composer. But, in the absence of a stable persona, the implied composer, like the listener, would confront a musical object that is somewhat inhuman in its lack of determinate, unified agency.15

In The Composer's Voice, Cone discusses solo vocal music with piano accompaniment in terms of a triad of personas: a vocal persona, a pianistic persona, and, of course, an encompassing composite persona. More recently, he has found a way to reduce the complexity by regarding the vocal persona as a composer: the piano sounds transcribe the musical thoughts of the vocal persona, and consequently the whole texture can be understood in terms of "a unitary vocal-instrumental protagonist that is coextensive with the persona of the actual composer of the song."16 My remarks on indeterminacy can lead to an alternative account. Cone has observed that "the voice is inevitably the most fully human element in any musical texture in which it takes part." (p. 123) I would add that this humanity brings with it a determinate individuality, setting the vocal line apart from the flux of agency characteristic of instrumental music. But what if the accompaniment of a solo song were to resist unification into a pianistic persona or incorporation within the vocal protagonist, instead retaining the indeterminacy that I have been describing? The agent established by the vocal line would be surrounded by, and isolated within, a world of gestural activity without other human beings.

A composer need not recognize, or utilize, this possibility of the medium. But the isolation of the solo voice within its musical world may help to explain the prevalence in Romantic song of such concerns as estrangement, wandering, unhappy love, and so on. In Cone's terms, the expressive potential of the texture points toward that range of subject matter.

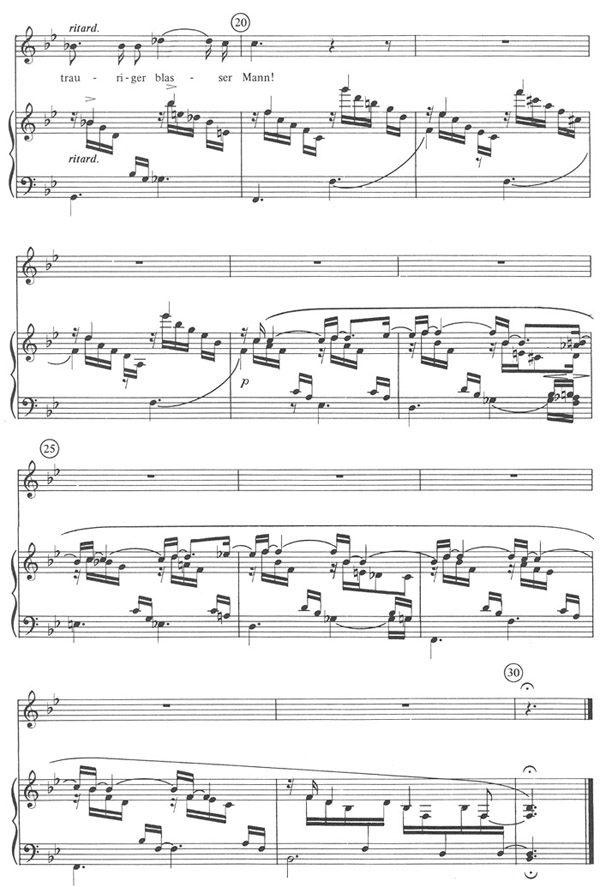

"Am leuchtenden Sommermorgen" (song 12 of Schumann's Dichterliebe) raises questions about the relation of vocal part and accompaniment by continuing the piano music into a postlude. (ex. 2) The interpretation of the postlude, then, constitutes a rather special case of the interpretation of accompaniment.17 The text might suggest a simple solution. The protagonist describes himself as wandering through a garden, where the flowers give him a consoling message: accordingly, the postlude, and perhaps the piano music throughout the song, can be understood as a representation of the flowers' speech or song.

Example 2: Schumann, Dichterliebe, op. 48, "Am leuchtenden Sommermorgen"

Am leuchtenden Sommermorgen

Geh' ich im Garten herum.

Es flüstern und sprechen die Blumen,

Ich aber wandle stumm.

Es flüstern und sprechen die Blumen,

Und schau'n mitleidig mich an:

Sei unserer Schwester nicht böse,

Du trauriger blasser Mann!On the gleaming summer morning

I go about in the garden.

The flowers whisper and talk

But I wander mute.

The flowers whisper and talk

And look at me sympathetically:

"Don't be angry with our sister,

You mournful, pale man."

But this account simply accepts the protagonist's view of his situation. Whatever sympathy one may feel for him, a man who thinks he hears the speech of flowers is likely to be deluded. Perhaps an interpretation should retain more distance from such a protagonist. In fact, the protagonist has already quoted the melody that goes with the flowers' message. It is not the same as the melody in the postlude, and the flowers' words do not fit the new melody. The point of the postlude, then, may be to subvert the protagonist's claim: whatever the postlude may represent, it is not the address that the protagonist thinks he hears.

However, further arguments for the first interpretation are available. Even if the postlude presents new material, it continues smoothly from the explicit quotation of the flowers. (ex. 3)

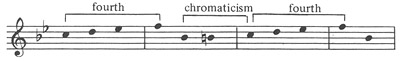

Example 3: Motivic links at end of vocal line and beginning of postlude in "Am leuchtenden Sommermorgen"

A. Vocal part, mm. 17-20, with step-related thirds marked

B. Upper line of piano part, mm. 20-23, with registral changes and marking to show step-related thirds (cf. A above)

C. Upper line of piano part, mm. 20-23, showing registrally isolated descent through a fourth

D. Upper line of piano part, mm. 23-24, showing ascending fourth-motion (cf. C above)

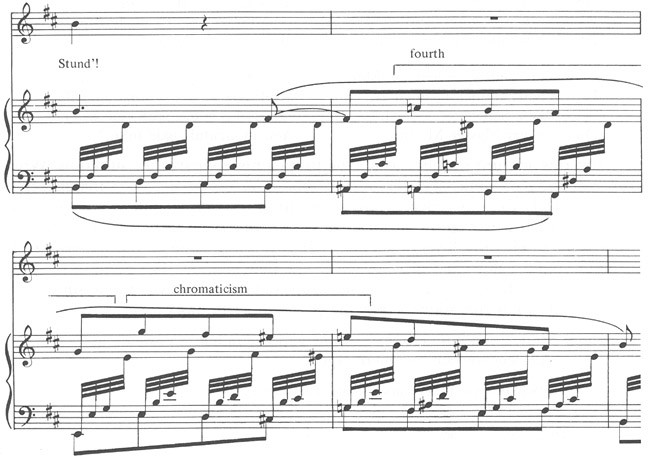

The chromaticism, and the stepwise motion through the interval of a fourth, link it to the postlude of "Ich will meine Seele tauchen" (song 5 of the cycle), another song in which a flower is said to sing. (ex. 4) One can cite a resemblance between the postlude and the phrases from Blumenstück that I discussed earlier.

Example 4: Material shared between two songs in Dichterliebe

A. Melody from postlude of "Am leuchtenden Sommermorgen," mm. 23-26

B. Beginning of postlude in "Ich will meine Seele tauchen" (song 5). mm. 16-19

The silence of the protagonist, as he has stated, occurs when the flowers whisper and murmur: he is silent during the postlude, and so this must be their intervention. But further arguments against this position are also possible. The protagonist hears the flowers speak, but the postlude is wordless. He sees the flowers face to face, in bright sunlight, but the postlude is invisible. And there is something very strange about a protagonist who announces that he is silent, and yet quotes the words that he claims to hear.18

My comments on Blumenstück can imply analogous arguments for the indeterminate agency of the piano accompaniment here, but two points are worth mentioning. Given the protagonist's claim to hear speech, the texture of the piano accompaniment seems pointedly ambiguous. The melody of the postlude, and to some extent the sustained high notes throughout the piano part, might imply a voice; but they can also be heard as the retention of pitches from a non-vocal arpeggiation figure. Further, the sixteenth-note delays of the sustained high notes, suggesting halting speech, result from a mechanical regularity in metrical placement, a matter of arithmetic; this last ambiguity threatens to undo even the impression of gesture, reducing the music to pure patterning of sound.

In short, the song leaves its listener poised between two incompatible interpretations of its instrumental component. The protagonist, already deprived of contact with his beloved, may nonetheless be hearing the unified, comforting voice of the flowers, standing in for her and addressing him in her absence; or he may be hearing his own voice, in an act of prosopopoeia that offers, at best, a comforting illusion of communication.

At this point, it is a relatively small interpretive step to regard the song as an allegory of musical interpretation. The listener, deprived of the composer's presence, may hear the voice of a "spokesman,"19 but such a voice may be only an effect of figurative language. And the song, understood allegorically, yields still a new puzzle. If instrumental music cannot be said literally to speak, neither can it be regarded as a familiar natural object, a plant that receives a voice through anthropomorphism. The further irony of the song is that the accompaniment, like any instrumental music, eludes both of the interpretive models offered by the text.

In the protagonist of this song, we can hear a figure for one familiar voice of the interpreter. Of course I am tempted to hear, in the ironic undercutting of the song's capacity for self-description, the voice of the composer himself.20

1Musical Form and Musical Performance, 93.

2"The Authority of Music Criticism," in Music: A View from Delft, ed. Robert Morgan (Chicago, 1989), 109.

3"Schubert's Promissory Note: An Exercise in Musical Hermeneutics," 19th Century Music 5 (1982): 233-41.

4W. K. Wimsatt, Jr., and Monroe C. Beardsley, "The Intentional Fallacy," in The Verbal Icon, by W. K. Wimsatt, Jr. (Lexington, Ky., 1954), 5.

5Wayne C. Booth, The Rhetoric of Fiction (Chicago, 1961). In The Composer's Voice (p. 2), Cone acknowledges the influence of this book.

6Cf. Cone's comment on a passage in the Hammerklavier: "the composer's intention is to convey a sense that the pianistic persona itself, rather than the player, is improvising." (The Composer's Voice, 130)

7Booth, Rhetoric. See pp. 70-73 for Booth's introduction of this concept.

8Further, "the well-composed song should convince the listener that the composer's voice is both musical and verbal—that the implicit musical persona, surrounding and including the protagonist, is creating words, vocal line, and accompaniment simultaneously." (p. 22) (Cone sometimes uses the term "implicit musical persona" as a variant for "complete persona"; see p. 57 for a comment on this usage.) And when Cone writes that the notion of composition as dramatic impersonation "might . . . prove a tool for examining such concepts as the alleged insincerity of Lizst's music and the simple piety that is supposed to shine through Bruckner's," (p. 3) his remarks recall Booth's claims for the notion of the implied author: "It is only by distinguishing between the author and his implied image that we can avoid pointless and unverifiable talk about such qualities as 'sincerity' or 'seriousness' in the author." (The Rhetoric of Fiction, p. 75)

9The following passage carries on in a similar vein: "Perhaps, then, my original disclaimer of any mystical content in the concept of identification was too sweeping. The apprehension of the unity of the musical work, and of the union of work with self, is clearly analogous to the experience reported by the mystic of his relations with the One." (pp. 156-57)

10In its juxtaposition of authority and intimacy, the passage conjoins the theological and interpersonal models for musical experience.

11Another example is more complex. Cone cites the Fantastic Symphony as a revealing model of instrumental music: "In choosing as his persona a figure identifiable as Berlioz but not identical with Berlioz, the composer was symbolizing—no doubt unconsciously, but nonetheless appropriately—the relationship of every composer to his musical voice." (p. 85) While stating that the persona of a composition is not "identical with" the composer, this sentence raises the further possibility that every persona is somehow "identifiable as" the composer.

The passage continues: "The persona's experiences are not the composer's experiences but an imaginative transformation of them; the reactions, emotions, and states of mind suggested by the music are those of the persona, not the composer." Early in this sentence, the notion of "imaginative transformation" retains ambiguity in the distance it proposes between the composer and persona; the composer's experiences are said to provide the initial material that is transformed into the persona's experiences, and the nature of this unspecified transformation will determine the eventual relation between the listener and the composer, which might still be intimate. The flat assertion that ends Cone's sentence does seem to deny some of the suggestive implications of the preceding material; but perhaps one can retain a sense of tension between this conclusion and the preceding assertions, reading the movement of these sentences as replicating and dramatizing the conflicting impulses that I am ascribing to Cone's position.

12Paul de Man's discussions of prosopopoeia are valuable; see especially "Autobiography as De-Facement," in The Rhetoric of Romanticism (New York, 1984). De Man's influence is present at several points in this paper; for a clear account of relevant material in de Man, see Minae Mizumura's excellent essay "Renunciation," in The Lesson of Paul de Man, ed. Brooks, Felman, and Miller (New Haven, 1985).

13Certainly this notion of "interpretive temptation" is the point at which I am furthest from Cone's own statements. But in "Schubert's Promissory Note," where Cone writes of temptation as the extramusical theme of a Schubert piano piece, the language of interdiction and transgression drifts over into his account of his own task: the final stage of his argument is "an attempt to answer what is possibly a forbidden question. What context might the composer himself have adduced?" (p. 240)

14I present the claim in more detail in "Music as Drama" (Music Theory Spectrum 10 [1988]); the discussion of string quartet texture in that article suggests that textural indeterminacies are not confined to keyboard music.

15That is, the music is "inhuman" relative to common, reassuring ideas about the integrity of individual human agents. It could be argued that the unity of actual human agency is dubious or fragile, and that the fiction of a unified musical persona is valuable precisely as an assurance of the listener's own coherence and integrity. For related argumentation, see the essays in Neil Hertz, The End of the Line (New York, 1985), for instance "The Notion of Blockage in the Literature of the Sublime." Another essay in Hertz's collection, "Freud and the Sandman," is a fine discussion of "the wish to put aside the question of figurative language." For a clear account of important problems about agency, see Thomas Nagel, "Moral Luck," in his Mortal Questions (Cambridge, 1979).

16"Poet's Love or Composer's Love?" (manuscript) This essay, which treats Schumann's Dichterliebe, was presented at the conference "Music and the Verbal Arts: Interactions" (Dartmouth College, May, 1988) and is forthcoming in the proceedings of that conference.

17And, since the same material appears in the postlude that concludes Dichterliebe, the interpretation of song 12 must have important consequences for the interpretation of the whole cycle. I hope to present a more comprehensive account soon in another paper.

18Another interpretive possibility emerges in the critical literature. Martin Cooper describes the postlude as "another voice, this time the piano's," coming, like the flowers' speech, to offer consolation ("The Songs," in Schumann: A Symposium, ed. Gerald Abraham [Westport, Conn., 1977], 107). This reading acknowledges a change of voice, but otherwise retains the protagonist's perspective with no questioning or irony. Eric Sams writes more ambiguously of the "sonorous image of a voice sighing and singing hidden among flowers" (The Songs of Robert Schumann [London, 1969], 119). In discussing the last song of the cycle, Nicolas Ruwet, somewhat like Cooper, describes the piano postlude as the intervention of a benign character—"comme si la musique, alors même que tout est dit, essayait encore de venir combler un manque" (Langage, musique, poèsie [Paris, 1972], 62). I would question all these interpretations; it may be that the commentators have succumbed to the delusion that overcomes the protagonist of the song.

19Cone cites Wilson Coker's description of the composition as "an organism, a sort of spokesman who addresses listeners." (The Composer's Voice, 5)

20An early version of this material was presented to the Colloquium on the History of Ideas at Wellesley College, October, 1988; I am indebted to the participants, whose responses enabled me to clarify and improve this paper.