Several years ago Gerald Moore, the justifiably renowned pianist, recorded a singularly witty lecture on the Romantic art song and the problems of its performance. The resulting album was entitled The Unashamed Accompanist and has been installed as required listening for my nineteenth-century music history classes for several years. Somewhere, buried among the countless gems of typically English humor recounted therein, Mr. Moore resurrected for yet another generation of students the old story about "a certain authoritarian maestro," Sir Thomas Beecham. When queried after an operatic production about the fact that his orchestra had overpowered the singers to such an extent that only an occasional hiss projected from the stage, Sir Thomas was reported to have replied, "Yes, yes, I covered the singers. I did it on purpose. I did it, in fact, in the interests of the public!"

Having labored in the orchestra pits of numerous theaters and opera houses during the past two decades, I have always managed a sympathetic chortle at that statement. Further, orchestral practicum of this sort has contributed to certain of my difficulties in presenting students with an unbiased view of nineteenth-century operas. Specifically, those textbook comments which represent such entertainments as "occasionally sacrificing dramatic consideration in favor of purely musical ones" have always struck me as ludicrously charitable . . . occasionally indeed!

When viewed from the pit, the operatic stage is a veritable treasure trove of galling convention. Thus it is that for me, lolling down there in the brass section—dutifully counting one hundred and forty-seven measures of rest in order to realize the singularly gratifying experience of playing eight measures of monotone upbeats, pianissimo!—the tenor has become a most deserving focus of vituperation.

There should be no misunderstanding here. The fact that composers and librettists have so often found it necessary to dispose of the tenor at some point in the drama has never upset me; oh no, far from it! My complaint, rather, is that it invariably takes too long to effect this desirable end . . . and even when the inevitability of his fate has become obvious to all, the wretched fellow nearly always hangs on—interminable in the throes of his terminal condition—for an insufferable time!! I have even entertained the notion that tenors are buoyed in their superhuman efforts to remain alive on stage (and singing through it all!) by the knowledge that, in so doing, they delay the only joy that we orchestral musicians can expect from this otherwise thankless exploitation of our modest talents, i.e., the conferring of the paychecks!

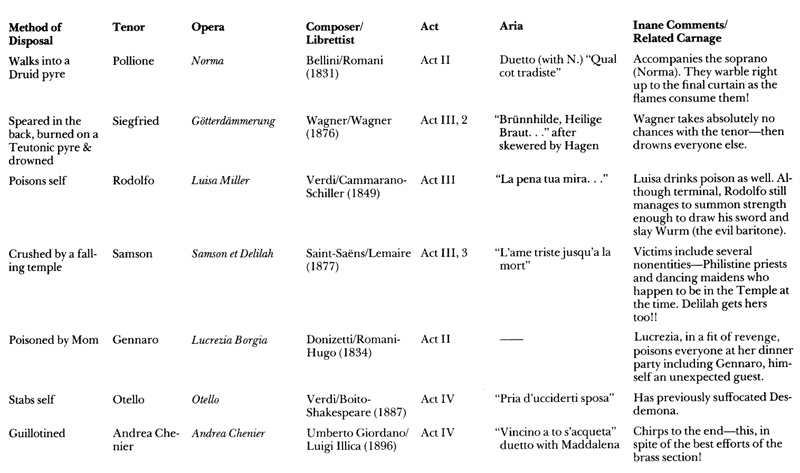

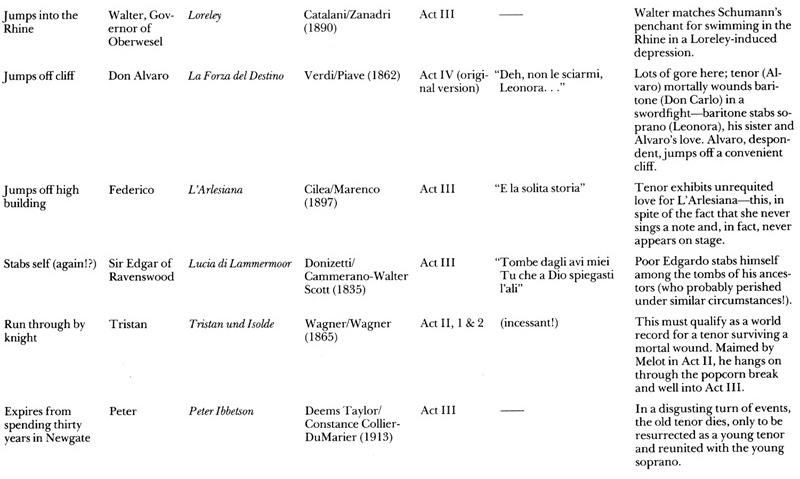

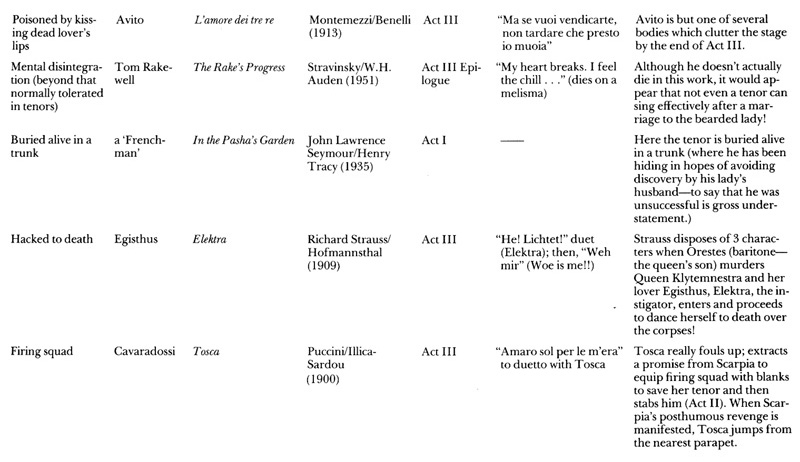

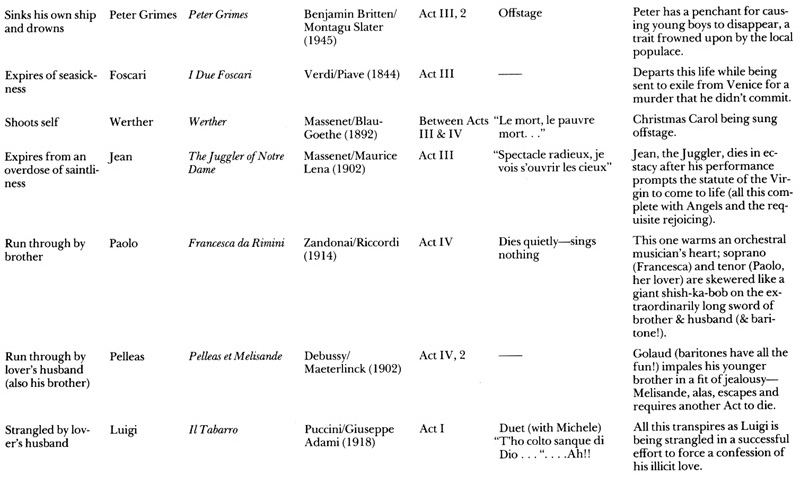

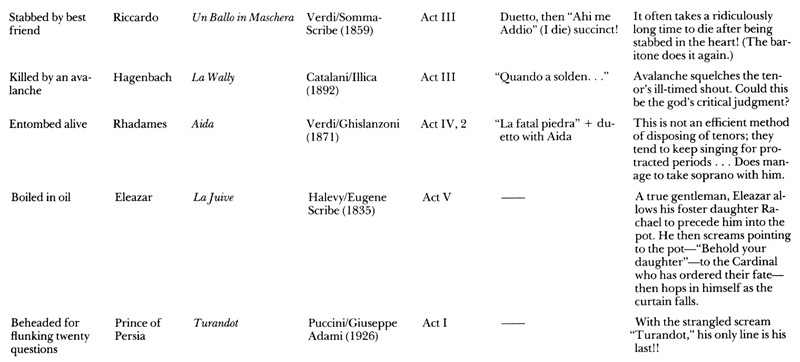

Decades of anti-tenor bias remain heaped in an uncleaned corner of my psyche, ripe raw material from which the present tongue-in-cheek study was concocted. A chart, appearing here as Appendix B, has been included in order to facilitate therapy and at the same time stimulate ongoing discussion. Although it makes no claim to being complete (note that blank spaces are provided for the benefit of do-it-yourself leisure time activity), those entries which are included represent three centuries of a delightfully macabre tradition.

It seems obvious that composers and librettists competed in their efforts to be innovative in ridding the operatic stage of its tenors—even a cursory examination of this list reveals a remarkable diversity of approach in this regard.

An inordinate number of the tenors who appear in the surveyed operas commit suicide (see Appendix A). The favorite rationale for this rash of bizarre behavior is the theory that it stems from romantic complications with the diva. In exercising this one redeeming aspect of their collective personality, tenors display a refreshing diversity of approach: four jump off or into something (including Eleazar's inspired swan dive into a pot of boiling oil in La Juive!); three depart the stage by stabbing themselves; one opts for poison while still another uses the quicker, but decidedly messier solution of shooting himself. Ah, but it remains for the Romantics in this group of tenors to provide us with truly creative suicides. Witness, for example, the sad end of Samson who, with Biblical finality, pulls a temple down upon himself, the evil soprano and a cast of thousands. Then, there is the hero of Britten's masterpiece Peter Grimes, who scuttles his boat only to discover that he's never learned to tread water. And finally there is the strange case of Bellini's Roman tribune Pollione (Norma) whose infatuation with a Druid Priestess concludes with the protagonists voluntarily transforming themselves into burnt toast. It should be noted that, like many of the more elaborate attempts at reducing the tenor population, the foregoing events are accomplished offstage (much to the relief of the stage manager!). Thus, although again cheated of witnessing our antagonist's deliciously gory demise, we musicians do gain a measure of satisfaction in this case when, like Nero, we fiddle while Pollione (and Norma) burns.

Although most often the tenor perseveres to the final act (in accordance with the importance of the character portrayed and the supposed demand of the drama itself), there have been sporadic instances of accelerated exits. Notable in this regard is Puccini's treatment of the Prince of Persia in Turandot. Actually the unfortunate Prince is separated from his head in the very first act, ostensibly for his failure to solve the three enigmas posed by the Mandarin, Turandot herself. However, it is entirely possible that his demise resulted from the only truly unforgivable failing in a tenor, i.e., his failure to break into bel canto at the slightest provocation. Not only does the Prince of Persia remain uncharacteristically tuneless but he departs the scene after having uttered only one word, "Turandot." Puccini doesn't continue this brief respite for the harried musicians, however; he provides us with another, far more vocal Prince in Turandot and this tenor characteristically warbles his way into the girl's heart by the opera's end.

Baritones seem to be favored as executioners, a task that they no doubt relish, given the subordinate singing roles that most are accorded! Baritones of my acquaintance seem to particularly enjoy stabbing and throttling tenors . . . Un Ballo in Maschera (Verdi) and Il Tabarro (Puccini) are notable, although examples of this sort of baritone/tenor enmity are seemingly endless. In these instances and, in fact, usually, the baritone is driven to perform bodily harm to the tenor because he perceives himself to be cuckolded by the rascal's attentions to his lady. Thus, time and time again tenors are maimed and murdered—ostensibly to preserve the questionable virtue of a soprano. However, there is some support for the theory that baritones just don't like men that sing high. Hence, given a suitable weapon, they tend to rush around the stage—not unlike crazed mongooses—savoring their chances to rid the world of its musical serpents! Such is the case when, in Tristan, Wagner has Melot charge in to deliver the eventually fatal swordthrust although it is King Mark (the saccharine Basso!) who has all of the reason to act. Often the baritone, humanitarian do-gooder that he is, manages to dispose of his other irritant (and ours), the soprano . . . but that is, of course, another story. . . .

Occasionally the tables are turned when a particularly malevolent tenor skewers his unsuspecting rival. Don Alvaro does just that in La Forza del Destino before jumping to his death, and Rodolfo (Luisa Miller) even manages to dispatch a baritone with a well placed sword thrust although hopelessly poisoned himself.

Perhaps the most overused of a multiplicity of "dramatic" conventions encountered in these works is the presence of some kind of baritone/soprano/tenor involvement, and the variations appear to be endless. An obvious example is provided in the Tristan/Isolde/King Mark triangle, a situation notable also for the remarkable ability of its tenor to survive with a mortal wound for an extraordinary length of time. It should be noted here that Wagner learned from this experience, for in Götterdämmerung he contributes the most deliciously thorough end for a tenor (Siegfried is skewered, roasted and drowned) in all of operatic history!

Although one might expect such behavior from Wagner, in fact many other composers and librettists have proven to be equally bloodthirsty in their solutions to "the tenor problem." Not infrequently his demise prompts a similar fate for others in the cast and I have catalogued several of these instances in the column entitled "Related Carnage" in Appendix B. Given every tenor's preoccupation with the soprano, it is not surprising to find that many of the bodies strewn about in these "dramas" are female. Verdi seems unusually adept at a kind of male/female binary form that I like to think of as "Tomb for Two." Rodolfo poisons himself and induces Luisa to do likewise in Luisa Miller; Otello suffocates Desdemona before stabbing himself; and of course there is the sad fate of Rhadames and Aida, who find themselves entombed alive. Incidentally, this last method, while suitably Egyptian and decidedly grizzly, ranks low on the orchestral musician's preferred list of tenor disposal methods—the principals tend to keep singing until the air runs out; a protracted period indeed! In at least one notable instance a tenor is hastened to his final reward by an "Act of God." The fate of the brave Hagenbach in Catalani's La Wally would seem to lend support to the little known (and quite theologically unsound) theory that the Creator himself harbors anti-tenor sentiments, for here the high-pitched hero is literally crunched in mid bel canto by a timely avalanche.

Unique circumstances posed in several of the surveyed operas have spurred librettists to truly masterful solutions. In The Rake's Progress, for example, Rakewell's dissolute life—punctuated by an unfortunate interlude with a bearded lady no less!—has a decidedly negative effect upon his ability to sing by opera's end. Another exemplary situation is exploited in Montemezzi's L'amore dei tre re. Avito is archetypical, enmeshed in several of the conventions discussed previously. Here, the standard love triangle, complete with the obligatory enraged baritone, results in the ultimate demise of all of the major characters, but the methods employed reflect the consummate panache of librettist Benelli. The carnage begins in Act II when Fiora (soprano) is throttled by the blind King Archibaldo (basso) in a fit of frustration over not being able to extract from her the name of her lover (Avito, of course!). Archibaldo, you see, received Fiora as a peace offering from a conquered neighboring country. He, in turn, married her off to his son, Manfredo (baritone). The carnage resumes in Act III. Fiora's body (stone-dead since the last act) is displayed on a bier as Avito—the tenor who caused all of this in the first place—slithers in and plants a kiss on the stiff soprano's lips; he then promptly feels ill. At this point Manfredo emerges from the shadows and informs the unlucky tenor that he poisoned his dead wife's lips in a successful effort to avenge himself. Avito then expires after the required aria—delivered presumably in the agonized spasms preceding the final event. Finally—and whereas it is totally unacceptable for a baritone to realize such a total success—Manfredo jumps on the bier, kisses his wife (whose lips are by this time bruising noticeably from overuse!) and dies. Blind old Archibaldo stumbles in and over all of the bodies at the opera's conclusion.

It is of course important to affirm the fact that the continuing vitality of opera is due in very large measure first to the quality of singing and then (very secondarily!) to the dramatic spectacle that provided the excuse for it. Thus we long suffering orchestral musicians must be prepared for the inevitability of it all. Tenors will continue to sing to the last breath, and beyond—in this performance and the next—since, fortunately for us as well as for them, the foregoing catalog is in no way permanent. We long suffering orchestral musicians for our part will undoubtedly continue to provide the necessary, if unsatisfying, accompaniment for them—provided, of course, that the paycheck serves to return us to reality, just as a curtain call at the drama's end serves as the cue for the miraculous resurrection of our friends on the stage.

APPENDIX A

Thirty Tenors Meet Their End!

Jumps off or into something: 4 (includes boiling oil bit) Sundry Suicides: 5 (Falling temple: 1) (Drowns by sinking own ship: 1) (Walks into Druid pyre: 1) (Entombed alive by choice: 1) (Shoots self: 1) Swords and Knives: 8 (Self-inflicted stab wounds: 3) (Administered by others—all baritones!: 5) Strangulation: 1 Poisoning: 3 (Self-inflicted: 1) (Administered by others: 2) Firing Squad: 1 Guillotine: 1 Speared/Burned & Drowned: 1 Fate/Accidental: 5 (seasickness, buried alive; saintliness; avalanche; creeping insanity) Old Age: 1

APPENDIX B

DELICIOUS DETAILS