Analysis, by Ian Bent with William Drabkin. New York: W.W. Norton, 1987. 184 pp. ISBN: 0393024474

Music Analysis in Theory and Practice, by Jonathan Dunsby and Arnold Whittall. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988. 250 pp. ISBN: 0300037139

The two books under review here are devoted to the topic of musical analysis. The appearance of such books reflects the growing significance of analysis in virtually all aspects of musical study within the United States. (The geographical limitation is significant and I'll come back to it later.) Analysis forms an integral part of most undergraduate and graduate programs in history, theory, criticism, and performance; and in the professional journals one can hear the analytical wheels turning within different kinds of studies. It is analysis that often provides a link between studies with differing foci; its prominent role in some studies makes it difficult to determine a historical or a theoretical orientation. Indeed, the growing interest in analytically based studies is making some traditional distinctions between disciplines seem blurred, if not meaningless.

Due to the burgeoning interest in analysis within the profession, it is all the more important that analysis itself be a subject of scrutiny. The questions that need asking are the fundamental but "hard" ones: what is analysis, what does it tell us, how does it work, and why do we need it? The books under review here either explicitly address these questions or implicitly take a position. My review focuses on these hard questions, considering other issues as they pertain to them.

Analysis by Ian Bent with William Drabkin is an expanded version of Bent's article of the same title that appeared in the New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (Washington, D.C.: Grove's Dictionaries of Music, 1980). As is indicated in the book's Preface, additions to the article include Drabkin's glossary, which defines analytical terms used in the twentieth century; discussion of developments in analysis since 1975; presentation of set-theory methodology; and amplified discussions of "Renaissance diminution theory," "figured-bass and harmonic theory," and "nineteenth-century theory" (p. viii). The first chapter of the book, "Musical Analysis in Perspective," addresses the hard questions about analysis. Chapters 2 and 3 are historical surveys of analytical approaches and concepts. This history begins with some early analytical trends from the Middle Ages to 1750. It then considers the "emergence" of an "analytical approach and method" from 1750 to the late nineteenth century and continues with a study of analysis "as a pursuit in its own right" from the late nineteenth century to recent times. The fourth and final chapter, "Analytical Method," presents eight different analytical approaches from a methodological perspective.

Analysis is an astonishing overview of analytical approaches to music. Its breadth of information and evident concern for detail provide a welcome depth. The book is further significant for bringing together in an illuminating way disparate ideas and materials pertaining to analysis and for raising and providing answers for the hard questions about musical analysis. My critique is an attempt not only to "review" the book's stance to these hard questions but also to review the questions themselves in an effort to clarify the nature of analysis and its role in modern thought about music.

Chapter 1 begins by considering "The Place of Analysis in the Study of Music," showing its relation to other areas within the field of musical study: its relation to aesthetics, theory, history, and criticism. The question of whether analysis is a separate or autonomous domain of study underlies these relations. Bent affirms the autonomy of analysis, but at the same time is careful to show its strong ties to other areas of study.

The decision to treat analysis as an autonomous domain is not an obvious one. It would be neither conservative nor naive to consider analysis a tool for other sorts of musical activity from technical aspects of composition to philosophical questions of aesthetics. While the topic of analysis gains focus and a certain amount of definition as an autonomous study, the sense of function and purpose of any particular analysis is lost. The analytic activity and results change, chameleon-like, with their overriding purposes, be they theoretical, historical, critical, or compositional. If one chooses to consider analysis as a separate domain of study, one must be sensitive not only to the purposes of an analysis (to argue for a historical dating of a piece, to demonstrate a theoretical concept, for example), but also to the purposes for which the analytic method was developed. Analysis itself must be established as an epistemological apparatus, not simply a means of empirical discovery.

Given the notion of analysis as autonomous, let's now consider Bent's conception of its relation to other domains of musical study—aesthetics, theory, history, and criticism. For each, Bent points out the similarities and differences and the extent to which analysis serves the goals of a particular focus of study. Below I shall consider together the domains of aesthetics and criticism and history and theory.

Bent demonstrates that both the aesthetician and the analyst are "in part concerned with the nature of the musical work" (p. 2) and shows how the work of the aesthetician feeds into that of the analyst and vice versa. The central point of contact between criticism and analysis lies in the "descriptive and judicial" (pp. 3-4) features of both kinds of activities. Analysis, by its fundamental choices of what features of a piece to include and exclude and its choices of what pieces to analyze, has an implicit judicial component, while that component is explicit in critical work. Both analysis and criticism rely explicitly on description as a means of presentation and articulation of the analytic or critical subject.

Bent demonstrates how on the one hand, analysis is a tool of historical inquiry and on the other, historical method is a "tool for analytical inquiry." Further, he claims a special relation between these two domains: "Historical and analytical inquiry are thus locked together in mutual dependency, with things in common as to subject matter and with completely complementary methods of working" (p. 3). One might have thought that this special relation would hold between analysis and theory—but not for Bent: "Many would deny a separation of any kind and would argue that analysis was a subgroup of musical theory. But that is an attitude that springs from particular social and educational conditions" (p. 2). Bent argues that since work from other domains has contributed significantly to the body of analytical literature, there is no basis for understanding analysis as a product or a tool of theory only. While there is a good deal of validity to this argument, it nevertheless disregards the important role theoretical concepts of musical structure play in analysis.

Since analysis is dependent on such concepts, one must consider how they are articulated. It does not seem unreasonable to define theoretical work as the formulation of concepts pertaining to music's structure. Even though a concept may be formulated for a historical purpose, the activity of formulation is itself theoretical. What seems most clear about these webs of relationships among various domains of study is the fundamental role of structural concepts in analysis itself. And with this realization comes the need to clarify the relation between the specific details or data observed in the analysis and the structural concepts that are brought to bear on it. One needs to formulate or at least be aware of the analyst's responsibility to the piece as a piece rather than as, for instance, an exemplar of a theory or a component in a historical problem. Even if we sometimes understand analysis as an activity that may stand alone, as when analyzing solely for the purpose of finding out what makes a particular piece "work," then the analytical activity must still include consideration of how structural concepts determine analytical observation and what role anomalous events play in the analytical results.

In choosing to focus on the four domains of aesthetics, theory, history, and criticism, Bent slights another area, namely performance. While performance is not an overtly scholarly activity it nevertheless is affected by the activities of historians, theorists, aestheticians, and critics. With its emphasis "on the music itself," analysis seems quite easily and naturally linked with performance. Although many claim the relevance of analysis to performance in the classroom, not much work has been done to develop that relation explicitly. It is a topic that deserves more attention.

The final portion of Chapter 1 presents some philosophical reflections on the topic of "The Nature of Musical Analysis," and while the discussion is little more than a page long, it covers several important issues. Defining analysis as an activity coming "to grips with" the music on "its own terms," Bent then turns to the problem of how one studies music that is "not tangible and measurable as is a liquid or a solid for chemical analysis" (p. 5). The choice of whether to study the score, live or recorded performances, the composer's intentions, or the listener's responses is a pre-analytic act that reflects issues beyond the activity of analysis itself, issues pertaining to intellectual and philosophical orientation. The choice itself has a bearing on analytic methods and results, and as such requires, in future critiques of analysis, a lengthier consideration. While Bent finds no agreement among analysts about what is the "correct" way to study the musical object, he does claim that the "score (when available) provides a reference point from which the analyst reaches out towards one sound-image or another, a 'neutral level' (to use the language of semiotics) which furnishes links between the creative activity and aesthetic experience" (p. 5). This claim raises a couple of questions. First, since notation itself incorporates notions about musical structures, its status as a "neutral level" of reference must be questioned. Further, the question about the relation between the visually apprehended structures of a score and the aurally apprehended structures of sounding music needs clarification. Second, since a score records the creative thought of a composer in the already structured language of notation, a question arises about how creative activity is to be defined: is it the composer's unnotated imagination, her doodlings at the piano, or her notated score? In other words, to use the score as a record or a path to a composer's creativity one must account for the mediating influence of notation either as a translating medium or as a determinant of creativity.

Bent concludes Chapter 1 with two reflections. The first concerns the place of differing analytic trends within encompassing philosophical and intellectual traditions. While not developing the idea, he points out that analysts (and, I would add, analytical systems) are marked by the ideas and concerns of their historical place. The survey of analytical concepts and methods places some within their intellectual context; and while I was left wanting more, it would be unrealistic to ask more from a study of this sort. In the end, I'm glad the issue is raised. Second, Bent points out that "the very existence of an observer . . . pre-empts the possibility of total objectivity" (p. 5). This observation makes clear the relation between analyst and analysis, a relation that needs to be made explicit. We value analyses for the "hearing" of pieces they present, a hearing inseparable from the analysts; and we have our students do analyses so as to help them "hear" better and perhaps more deeply. At any rate, the clearer we are about the function of the analyst in an analysis, about the role of the observer in observation, the more honest our analytic results will be.

The surveys of past and present analytic concepts and analytical methodologies constitute the body of the book (Chapters 2-4). Drabkin's glossary of terms is a welcome complement to these chapters. Anyone not conversant with all of the technical terms that pop up throughout the text (either in English or a foreign language) will find Drabkin's addition very helpful. Bent's discussion in the two central chapters is always clear and to the point. The following issues deserve special attention; others are discussed in an appendix, below.

In a reflective statement on the historical significance of Schenker's harmonic theory, Bent writes: "Schenker's harmonic theory represented a shift away from that of Rameau . . . , introducing the psychological notion of 'valuation'; that is, assessment by the hearer of chords and modulatory key areas in relation to longer-term pulls of tonality, and interpretation of them as either fundamental steps or elaborations of such steps. This valuation was the starting-point for the new way of hearing music—long-distance listening—for which Schenker has become so famous" (pp. 40-41). While there is no doubt that a psychological function is present in Schenker's notions, what we need now is a clearer understanding of the nature of that function. The need for such an understanding grows out of what seems to be a growing trend in music theory and analysis nowadays: the concern for listening-oriented (if not listening-based) approaches. It is no longer sufficient to say that a "hearing" or a "listener," is involved in an analytic approach; one must define the nature of that hearing and the nature of that listener.

A final matter has to do with the discussions of set theory in both the historical and the methodological chapters. In the former, set theory is considered along with other developments from 1960 to 1975 (among them phenomenology; the analysis of plain-chant; other mathematically-based theoretical systems; style analysis; and semiotics). Bent writes: "The proper formulation of a set theory of music has been the work of Milton Babbitt . . . , Donald Martino, David Lewin, and John Rothgeb . . ."(p. 63). He points out that Babbitt's work is "concerned with the 'ordered set'" and claims that it "belongs more properly within the realm of compositional theory" (p. 63). A little farther on Bent writes that the unordered set is more "generally applicable to analysis" and that the "most significant analytical contribution has been made by Allen Forte . . . " (p. 64). These statements are somewhat misleading. First, they bring up the issue of the relation between theory and analysis; without the pioneering theoretical work of Babbitt and the later clarifications by Lewin, Rochberg (mentioned earlier by Bent), and Martino, an analytical method could not have been developed. And further, much of the pioneering work and its clarifications were explicitly analytical. The issue, then, is not so much compositional theory vs. analysis but origins and developments and the strong relation between theory and analysis. Second, twelve-tone theory (which can be used for analysis) does consider unordered sets under combinatoriality. And third, the relevant function of ordered sets in an analytic context is not yet a dead question.

In the chapter on methodology, Bent discusses set theory as one of nine examples ranging among information theory, semiotics, phrase-structure analysis, and fundamental structure. The discussion of set theory "is an attempt to characterize the nature of the method" and not an explication of "principal terms and concepts" (p. 102). (Such an explication is included in the glossary.) Much of the discussion develops some set-theory concepts as analogs of tonal concepts in an attempt to show that what may appear as mathematically opaque to some musicians is not that dissimilar from musical notions with which we are all familiar. While there is some value in this, some of it is potentially misleading. For example, Bent compares projections of a set whose elements are "rotated" with the various arrangements of a triad, e.g., [1, 3, 6] may appear linearly as [3, 1, 6] and a G Major chord may appear linearly as B, G, D.1 In neither case does the rotation of the elements negate the identity of the set or chord. While there is a certain logic in this, what Bent neglects is the role of root function in securing the identity of the tonal chord. What I wish to point out with this example is not the usefulness or the futility of showing similarities between sets and chords but rather the need to consider active issues within the field of set theory. More discussion of other ways of conceiving intervallic and pitch functions within the confines of set theory would give a more accurate impression of the instability of the field nowadays. While there are certain dominant strains within set theory and analysis, the field is not conceptually static. This observation brings up the question of what such a survey should do when dealing with contemporary issues: should it reflect the dominant trends within the field or should it present the range of conflicting concepts, showing how each contributes to the broader scholarly enterprise? This is a question I will consider further in reviewing the second book.

Music Analysis in Theory and Practice by Jonathan Dunsby and Arnold Whittall focuses not on a history of analytical concepts and procedures but rather on contemporary practice of analysis: Further, the authors state that it is "premature to attempt a consistent overview of analytical issues from Bach to Webern, or from Aristoxenus to Forte, and [they] intend instead to show the discipline as turning prospectively and retrospectively around the axis of the early years of this century" (p. 9). The book is divided into four parts: Part 1 includes an introduction to the topic of analysis and a short historical survey, Parts 2 and 3 focus on tonal and atonal (their term) analysis respectively, and Part 4 presents semiotic analysis.

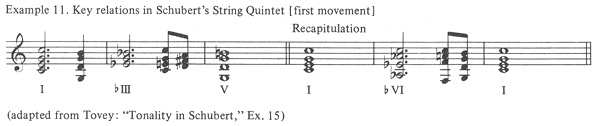

Parts 2 and 3 form the central portion of the book. Part 2 presents the fundamental features of tonal analysis from a Schenkerian perspective. Other approaches to tonal music (such as those of Tovey, Schoenberg, and Meyer) are discussed but always "against this Schenkerian backdrop" (p. 8). The first three chapters of Part 2 are "Schenker the Theorist," "Schenkerian Analysis," and "Developments of Schenker: Katz and Salzer." In the final three chapters, devoted to other approaches, one encounters statements such as: "And there are imaginative strokes in [Tovey's] technical descriptions of tonal structure—example 11 for instance [shown as Ex. 1 here],

Example 1. Dunsby and Whittall's Example 11.

where rhythmic notation is used to give hierarchical meaning to a tonal reduction (which is, however, meaningless from a Schenkerian point of view in its arbitrary voice-leading)" (p. 67) or "[Schoenberg's Fundamentals of Musical Composition] deals with the construction of themes, and with small and large forms (a concept Schenker considered quite misguided . . . )" (p. 81).

The Schenkerian "backdrop" is in evidence in the beginning of Part 3 as well. It starts with post-Schenkerian approaches to atonal music, proceeds to analyses of "Pitch-Class Sets," "Motives," "Form—and Duration," and "Twelve-Note Composition." Along the way the authors consider the question of whether the model of "organic structure" is apt for much twentieth-century music in the chapter "The Structure of Atonal Music: Synthesis or Symbiosis?"

Discussions during Part 3 present the predominant approaches to analysis of atonal music with little or no critical thought about the fundamental concepts. For instance, in the discussion of pitch-class sets the authors write: "The fact . . . that there are twelve different pitch classes but only six different interval classes . . . remains the cause of much theoretical debate, but it will do no great harm to our present purposes to accept it . . ." (p. 133). The basis for that debate is not articulated. The significance of the decision to present predominant analytic or theoretical notions arises when one considers the purposes or reasons for a book on analysis.

According to the authors, the purpose of the book "is to stimulate interest in music theory and analysis, not so much among those already committed and informed, but among skeptics and those who have so far read little or nothing on the subject" (Preface). There are two important issues here. First, let's return to the notion of geographical limitation on the growing significance of analysis I proposed in the opening paragraph of this review. While there may be skeptics of analysis within the United States, it is clear that analysis here plays an important role in both the teaching of music and in professional scholarly work. Thus, although published by an American university press, the book seems intended for a British readership; and here one cannot help but notice that the authors of both books under consideration are British. One can only speculate that such books on analysis are linked somehow to the present state of musical research in Britain. If, however, we imagine Dunsby and Whittall's book being read by skeptics in the United States, will this book convince them? I think not, because the book does not address those questions that an American skeptic would ask: how will analysis help me in my musical projects, be they performance, history, aesthetics, listening, or whatever? The second important issue involves the question of what an introductory book on analysis ought to present. Should it present the predominant approaches to analysis or should it provide a critique of the contemporary situation, detailing the debates and the issues, showing the breadth of analytical thought, and putting the analytical approaches into a larger intellectual context? Since analysis is not static but alive and changing, an introduction should strive toward the latter alternative, partly because it seems a more responsible position and partly because a so-called skeptic is more likely to be convinced by a consideration of the underlying musical issues than by a consideration of the technical details.

Now let me turn briefly to what I have called the "hard questions" about analysis. The authors rely on Boulez for an answer to the question "What is analysis?" They quote Boulez as saying that analysis "must begin with the most minute and exact observation possible of the musical facts confronting us . . ."2 (p. 3). The "facts" for Dunsby and Whittall are contained in the musical score. Further, they claim that "analysts who try to exclude from their accounts the impact of how the score sounds are rightly ridiculed (though there may be some ultimate purpose in trying to distinguish theoretically between 'sense' and 'sound')" (p. 10). This narrow definition of musical "fact" presents many problems when one faces, for instance, the ontological question of "What is music?" and the situation of pieces that may have no score or may have contradictory scores. It also reflects an apparent bias toward traditional Western music from the seventeenth to the mid-twentieth century.

Another issue concerns what analysis tells us. Dunsby and Whittall claim that analysis reveals features of compositions themselves but does not offer guidance on how to compose. As a means of revealing features of compositions, the authors conceive, like Bent, of analysis as an autonomous domain of study; unlike Bent, however, they are not concerned with its relation to other domains (an issue that will be discussed further below). As a consequence of this stance, Dunsby and Whitall emphasize the technical and systematic aspects of analysis as the means to revelation. Throughout the book one finds comments attesting to the need for clearly defined and systematic methods of analysis (for instance, "Tovey alone offered no allegedly systematic analytical theory to support the 'contention' [of a] 'best' explanation" [of tonal music] (p. 72).

The final issue concerns the question of "Why do analysis?" The authors write that "the main aim of the analyst is, through study, the enhanced understanding and enjoyment of particular compositions." (p. 4). Thus, analysis is a kind of personal quest for comprehension, but a quest that must be guided by rigorous technical and methodological standards. The authors are not concerned with how theoretical underpinnings of an analysis or the aims of the analyst will affect the analytical results. In fact, the activity we call "analysis" is diverse and has many purposes, some of which are not simply "enhanced understanding"; and these different purposes have a direct bearing on the results and practice of analysis itself. For instance, the authors write that the "book emphasizes 'analysis' rather than 'theory,' the practical application of particular techniques rather than the theoretical preliminaries which deal generally with technical matters." (p. 6). What is missing here is the complexity of the relation between analysis and its theoretical underpinnings. Theories are often developed from some sort of analysis. And analyses will often run up against pieces which do not fit the theoretical model. Does the analyst then throw the piece out as an inferior specimen or give up the model as inadequate? Where do the analyst's responsibilities lie—with the theoretical model or with the piece? If analysis is to be an autonomous discipline, then it must show an ability to offer a critique of its theoretical basis, to transcend any particular theoretical system as a means of understanding the work.

The relation of analysis to history is another issue. The authors assert that analysis, as yet, is not a very useful "servant of music history" (p. 7), an observation contradicted by exemplary instances of analytically-based historical studies.3 The authors' position on the relation of analysis and history raises questions of its own. Toward the end of the introductory chapter, they write, "Historical and critical awareness will probably exceed analytical experience to begin with, and the process of putting the latter at the service of the former (to such effect that the student's awareness may eventually be transformed) should never be rushed" (p. 9). Unless an analytical method incorporates some apparatus for assessing, and criticizing historical concepts, it seems that analysis is destined to fulfill the historical view, to "prove" given notions of the great works of music. Such a view precludes the possibility of analyzing the newest compositions, since there exists virtually no historical or critical awareness of these works. The relation Dunsby and Whittall assign to history and analysis is a restrictive one with problematic consequences. It is a relation that seems discordant with current notions of the relation between analysis and other disciplines in the United States.

Finally, the appearance of these two books is certainly of interest to anyone drawn to the topic of analysis as an autonomous discipline or as a tool for critical, aesthetic, historical, or interpretive studies. Both books raise important questions about the practice of musical study in the late twentieth century and about the methods and results of analysis itself. While some of these questions may ultimately have no answers, there is value in pondering them. Dunsby and Whittall's book is problematic in its uncritical focus on a limited number of analytical approaches and in its lack of concern with the relation between analysis and other disciplines. Bent's is more valuable for the detail of its historical studies, for its consideration of analysis as intimately related to other disciplines, and for the serious attention it pays to the wide variety of analytical notions that are available today. The latter seems especially valuable: without an attempt to comprehend, to embrace if you will, diverse notions of what analysis is or might be, there will be no informed, critical thought about analysis itself.

APPENDIX

Further comments on Bent and Drabkin's Analysis:

1. pp. 55-57. Bent discusses Tovey in a section titled "Empiricist Dissent," referring to his analyses as "narrating a purely musical process." At the end of the section, Bent refers to Tovey's repudiator "Hans Keller, for whom mere description is no substitute for real analysis." One wonders what constitutes "real" analysis and why description, which necessarily involves conceptual understanding, does not qualify as "real"?

2. p. 58. In a discussion of the use of information theory in various fields, Bent considers the "certain difficulties" that arise when the theory is applied to aesthetics. He writes: "For in the arts what information theory calls 'redundancy' (namely, confirmation of expectation, non-information) plays a special role in creating form and structure." This difficulty arises only if one understands "redundancy" as a negative rather than a statistical concept.

3. p. 62. In the section on set theory, Bent defines "equivalence": "Where several sets exist, certain relationships can apply among them: relationships of equivalence (in which one set can be reduced to another by some simple procedure) . . . ." The definition focuses on the process of demonstrating equivalence, not on the concept itself. For someone not familiar with the term, this definition would be of limited value.

4. p. 63. Bent identifies several new developments in music analysis between 1960 and 1975, one of which is the use of phenomenological philosophy for "discourse on music." After discussing a study by Ansermet and mentioning work by Batstone and Pike, he writes, "But no working method of analysis has yet emerged." This is a curious statement since such a "working method" is presented in Thomas Clifton's Music as Heard: A Study in Applied Phenomenology (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1983), which is cited in the book's bibliography.

5. p. 66. In discussion of new approaches to analysis Bent writes: "Aural analysis remains a seriously neglected field and a systematic theory will become an imperative when input of musical sound to computers for analysis becomes truly practicable." While there is no doubt that aural analysis has been neglected, the use of computers seems antithetical to the idea of it.

6. p. 69. Bent identifies the journal Theory and Practice as the "organ of two student societies in New York State." In recent years the journal has been presented jointly by the Music Theory Society of New York State and the Students' Theory Consortium of the Ph.D. Program in Music at the Graduate School of the City University of New York. The Music Theory Society of New York State is not a student organization and the editorial committee of the journal is formed by members of the Society.

1Bent gives a more complex example in the book on p. 103, comparing different rotations of a dominant-seventh chord and a [0, 1, 5, 6] set.

2Pierre Boulez, Boulez on Music Today, trans. Susan Bradshaw and Richard Rodney Bennett (London: Faber, 1975), 18.

3A few examples include Sarah Fuller, "Line, Contrapunctus, and Structure in a Machaut Song," Music Analysis 6 (1987): 37-58; Leo Treitler, "Meter and Rhythm in the Ars Antiqua," Musical Quarterly 65 (1979): 524-58; Richard Kramer, "Schubert's Heine," 19th-Century Music 8 (1985): 213-25.