Seldom does a composer parody his or her own style, and even more rarely does that composer acknowledge doing so. Yet the Czech composer Josef Suk does precisely this in a short piano lullaby entitled "Self-Parody on a Street Song" (1912). In this miniature, Suk appears to be lampooning one of his most popular pieces, "How Mother Sang at Night to the Sick Child" from the suite About Mother (1907). However, the "Self-Parody" can also be seen as a caricature of a general style of composition associated with Suk: the pedal-point ostinato composition. Several movements of his most famous works, including the andante of the Asrael Symphony (1904-07), the second movement of the Summer's Tale (subtitled "Noon," 1909) and two pieces from About Mother ("How Mother Sang" as well as the disturbing portrait "About Mother's Heart"), are composed around an ostinato pitch. In these movements, some for piano and others for orchestra, Suk's use of harmony and melody, usually densely chromatic and turgid, becomes particularly lucid, allowing the listener to hear the repeated pitches move in and out of consonance with the harmonies around them. Thus, these pieces serve as a primer to Suk's compositional style. In several of these works, the pitch level of the ostinato moves temporarily a tone or semitone away to fulfill both a musical and dramatic purpose: this is the "non-obstinate" aspect of the works. This study presents analyses of these movements, and investigates harmonic characteristics such as Suk's brand of extended tertian harmony, chromatic mediant harmonies, suspended tonality, and equal division of the octave in various levels of composition. Reductions of passages of Suk's music reveal a talent for employing a central motive at varying levels of composition. In addition, the analyses reveal self-quotations which inform the affective and programmatic realms of the works.

Suk and His Contemporaries

Antonín Dvořák considered Josef Suk his favorite pupil. Both Gustav Mahler and Alban Berg admired Suk's music. Although Suk's music today enjoys an international audience, it is has not reached the popularity enjoyed by his compatriots Leo Janáček and Bohuslav Martinů. Unlike these two revolutionary composers, Josef Suk never broke away from the chromatic style of the late nineteenth century. Rather, he embraced the chromatic innovations of Liszt and Wagner, and advanced them within a musical language that is at once personal and massive. The resulting music comprises rich chromatic polyphony and large but coherent musical forms. Of Suk's Asrael Symphony, John Tyrrell writes: "It is . . . one of the finest and most eloquent pieces of orchestral music of its time, comparable with Mahler in its structural mastery and emotional impact, but without Mahler's neuroticism."1

Although mentioning Suk's name in the same breath with such Post-Romantic Goliaths raises fewer and fewer eyebrows, there exists yet very little musicological and theoretical research concerning his music. The reason for this lies partly in the fact that most of the resource material concerning Suk is in Czech. Even more daunting to the would-be analyst is Suk's highly complex harmony. Neither of these factors, however, need to hinder the study of Suk's style. Although in this paper I refer to Czech sources, the theories therein are not dependent upon them. Furthermore, while the works that we will examine are representative of Suk's mature style, the pedal points in each help to make their design clear.

Suk's Evolution

While Suk's mature style indeed draws comparison to the music of German and Austrian composers of the turn of the century, his early music is far more frequently likened to the music his teacher, Antonín Dvořák, and with good reason. Suk's delightful early compositions—such as the Piano Quartet (1891) and Quintet (1893), the First String Quartet (1896), and the popular Serenade for Strings (1892)—are nearly completely in the vein of Dvořák. However, the same is true of early music of Janáček and Dvořák himself which is quite uncharacteristic of the representative styles associated with them.

Suk must have realized that his unfaltering emulation of his teacher would result in an artistic dead end, for in the years 1897-1905, his style changed markedly. It is within the incidental music for the play Radúz and Mahulena (later arranged in a suite entitled Fairytale [Pohadka]) that Suk's early Dvořákian period ends and a new, original voice begins. This phase in Suk's development, which Jaroslav Květ finds stylistically masculine,2 is sometimes called his "Radúzian" phase, partly because the works are painted in similar colors to those of Radúz and Mahulena, but also because the works include quotes from that work. During this period, Suk was quite happy and very much in love with his new wife, Otilka, Dvořák's daughter and a composer in her own right. We will refer to this period as Suk's "First Maturity." In addition to Radúz, important works dating from this period are the Four Pieces for violin and piano (1900), the suite Spring for piano (1902), the Fantastic Scherzo for orchestra (1903), and the music for the play Under the Apple Tree (1900-1). The period ends with the highly original Fantasy for violin and orchestra (1905).

The third and final period of Suk's career began in the face of catastrophe. In 1904, Antonín Dvořák, Suk's mentor and father-in-law, died. Only a year later, Suk's much beloved wife Otilka died of a heart condition. Suk's music from 1905 on testifies to the changes that these great personal losses wrought on Suk both spiritually and artistically. His language became infused with both a metaphysical expression and a very complex chromatic language that sometimes approaches bitonality. The most important pieces from this "Second Maturity" are the four massive orchestral works which are commonly referred to as Suk's great tetrology: the Second Symphony "Asrael," (A Summer's Tale [Pohádka Léta], Ripening [Zrání] (1917) and Epilogue (1920-33). Also significant are the piano suites About Mother and Things Lived and Dreamed (also translated as Through Life and Dream, 1909). Each of these works is divided into five movements or sections, with the exception of Things Lived and Dreamed, which is divided into two groups of five.3

The particular type of work we shall examine, Suk's pedal ostinato movements, all come from this Second Maturity. Although these works share common traits, each movement is a unique composition. While "Noon" from A Summer's Tale is composed primarily around a tonic pedal, "About Mother's Heart," from the piano suite About Mother, the second movement of Asrael, and the "Self-Parody" lullaby are all based on a dominant pedal. The ostinato pedal in "How Mother Sang at Night to the Sick Child," also from About Mother, is actually the seventh of a tonic chord of dominant seventh quality.

Symphony No. 2, "Asrael," Andante

The first movement we shall examine is the second movement of his Second Symphony, Asrael. (In Islam, "Asrael" is the angel who accompanies the souls of the dead as they journey into eternity.) The first three movements of the work are imbued with Suk's grief over the death of Dvořák. A primary motive of Asrael, our motive b, has its origin as the principal four-note motive which opens Dvořák's Requiem: a chromatic double neighbor figure (Example 1).4

Example 1: Principal Motive of Dvořák's Requiem (b).

Deriving from this figure, other double neighbor motions occur in different musical levels throughout Asrael. For example, the first movement begins in  minor, descends tonally to B minor at reh. 1, and then ascends to C minor at reh. 3 in a motion inversely related to the Requiem motive. The Requiem motive plays a greater role in the thematic and harmonic structure of Asrael's second movement.

minor, descends tonally to B minor at reh. 1, and then ascends to C minor at reh. 3 in a motion inversely related to the Requiem motive. The Requiem motive plays a greater role in the thematic and harmonic structure of Asrael's second movement.

The second movement of Asrael is Suk's first work based around an ostinato pedal. Within this movement, Suk developed a formula which he later adopted in other pedal ostinato works: he explores diatonic and chromatic harmonic regions which allow the pedal to remain largely consonant within their harmonic context. The form of Asrael's second movement is quasi-rondo, with episodes occurring at reh. 2 and 4, and a fugato at reh. 6. The music of the opening section, which features motive a in the first violins (Example 2), recurs at reh. 1, reh. 3 and three measures after reh. 8.

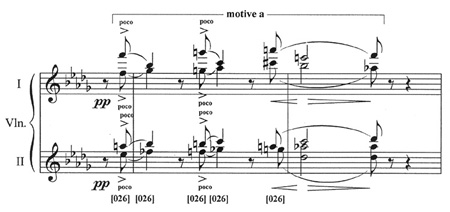

Example 2: Asrael Symphony, mvt. ii, violins, mm. 3 and 4, showing motive a and [026] harmonies.

Although the principal pedal tone of the second movement is  (which is registrally consistent at a minor ninth above middle C), a two-beat lower neighbor C begins the movement. The purpose of this "wrong note" anacrucis is twofold. First, the note leads us from the key of C minor of the first movement into the

(which is registrally consistent at a minor ninth above middle C), a two-beat lower neighbor C begins the movement. The purpose of this "wrong note" anacrucis is twofold. First, the note leads us from the key of C minor of the first movement into the  key of the second movement.5 Second, the chromatic juxtaposition echoes the Dvořák Requiem motive which is central to all of Asrael. This motivic connection becomes apparent when the motive is stated in full at reh. 1 (Example 3).

key of the second movement.5 Second, the chromatic juxtaposition echoes the Dvořák Requiem motive which is central to all of Asrael. This motivic connection becomes apparent when the motive is stated in full at reh. 1 (Example 3).

Example 3: Asrael Symphony, mvt. ii, 5 before reh. 1.

Through most of the movement the pedal tone occurs in the muted trumpet doubled in the flute. It is syncopated gently in an almost undetectable manner. Motive a in the muted violins begins at the end of the second measure and features ascending chromatic motion in the lowest voice, above which are heard whole-tone [026] chords, the derivation of which is soon to be revealed. The key is equivocal at first; however, the chromatic progression comes to rest in m. 4 on a  major chord. Thus, the pedal tone serves as the root of the opening key. At reh. 1, where the harmony moves to

major chord. Thus, the pedal tone serves as the root of the opening key. At reh. 1, where the harmony moves to  minor, the function of the

minor, the function of the  pedal remains constant as it serves as the third of the harmony (Ex. 3). In this same measure, the pedal tone seems to bend, first up to

pedal remains constant as it serves as the third of the harmony (Ex. 3). In this same measure, the pedal tone seems to bend, first up to  , and then down to C, thus stating the Dvořák Requiem motive, motive b. As the motive ends, the music of the movement's opening returns as the pedal tone once again becomes the root of a

, and then down to C, thus stating the Dvořák Requiem motive, motive b. As the motive ends, the music of the movement's opening returns as the pedal tone once again becomes the root of a  harmony.

harmony.

The next large harmonic change occurs three measures after reh. 2, first to  minor and next to

minor and next to  minor, where the

minor, where the  /

/ pedal again is consonant, serving as the fifth. The new motive in the English horn and trumpet combines with the triplet motive in the timpani in a funeral march. The harmony returns to the original tonic, this time within the parallel key of

pedal again is consonant, serving as the fifth. The new motive in the English horn and trumpet combines with the triplet motive in the timpani in a funeral march. The harmony returns to the original tonic, this time within the parallel key of  minor (notated in some of the instruments as an enharmonic

minor (notated in some of the instruments as an enharmonic  minor). One measure after reh. 3, the music of the opening returns again, this time accompanied by pizzicato strings doubled in the English horn. The Requiem motive then recurs one measure after reh 4.

minor). One measure after reh. 3, the music of the opening returns again, this time accompanied by pizzicato strings doubled in the English horn. The Requiem motive then recurs one measure after reh 4.

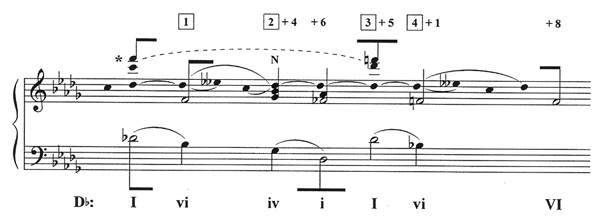

The harmonic motion to this point has been dictated by a middleground inner voice statement of the requiem motive b. The motive is seen in Example 4 at reh. 1 in the tenor line; it begins not on  , as does the foreground statement that begins in the same measure, but a sixth below, on F. The motion of this note to

, as does the foreground statement that begins in the same measure, but a sixth below, on F. The motion of this note to  propels the harmony to the subdominant; the subsequent motion to E (notated as

propels the harmony to the subdominant; the subsequent motion to E (notated as  in the example) becomes the third of the minor tonic. The initial F returns at one measure after reh. 4, just as the foreground Requiem motive returns in the clarinet. Although Filipovský asserts that Suk worked conscientiously against Germanic artistic influence, Suk's use of motivic parallelism in different levels of composition is a feature which his music nonetheless shares with that of German masters as well as with the music of his contemporary, Leo Janáček.6

in the example) becomes the third of the minor tonic. The initial F returns at one measure after reh. 4, just as the foreground Requiem motive returns in the clarinet. Although Filipovský asserts that Suk worked conscientiously against Germanic artistic influence, Suk's use of motivic parallelism in different levels of composition is a feature which his music nonetheless shares with that of German masters as well as with the music of his contemporary, Leo Janáček.6

Example 4: Reduction of opening section of Asrael Symphony, mvt. ii, showing Requiem motive at different levels of composition.

We may note at this point the static nature of this movement thus far. Although there are harmonic changes between  major and

major and  minor, the relative

minor, the relative  minor and the enharmonic minor subdominant

minor and the enharmonic minor subdominant  minor (notated in Ex. 4 as

minor (notated in Ex. 4 as  minor), it is not apparent whether these chords represent keys in their own right, or if they are harmonic areas within a central

minor), it is not apparent whether these chords represent keys in their own right, or if they are harmonic areas within a central  major tonality. After the ostinato tone becomes "subjected" to the Requiem motive one measure after reh. 4 (see Example 5), the tone ceases altogether at the first dynamic climax (nine after reh 4).

major tonality. After the ostinato tone becomes "subjected" to the Requiem motive one measure after reh. 4 (see Example 5), the tone ceases altogether at the first dynamic climax (nine after reh 4).

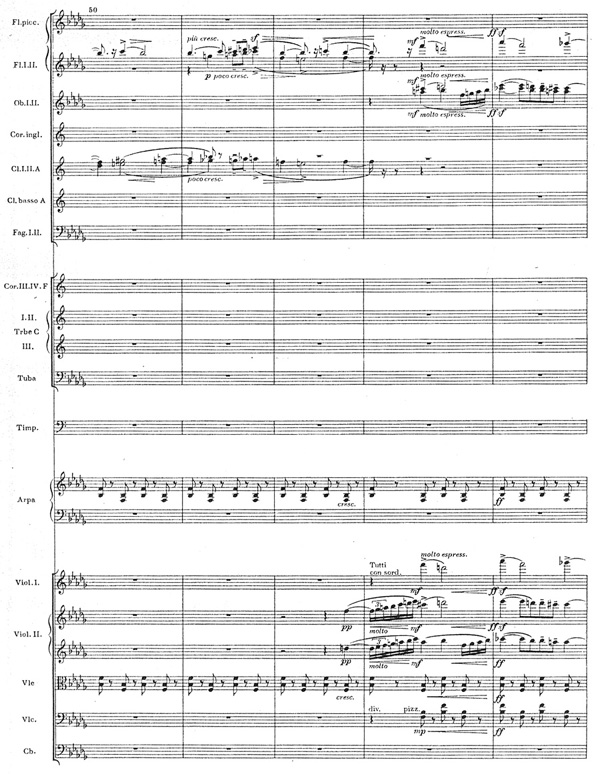

Example 5: Asrael Symphony, mvt. ii, reh. 4 and climax.

The harmony at this point is  major, a tonality to which the note

major, a tonality to which the note  would be foreign. The variant of motive a is heard in the violins and flute. The section at reh. 5 in which the pedal

would be foreign. The variant of motive a is heard in the violins and flute. The section at reh. 5 in which the pedal  returns is a variation of the first section. The harmonies formed are the same we had already heard in the previous section, but now they occur in more rapid succession (

returns is a variation of the first section. The harmonies formed are the same we had already heard in the previous section, but now they occur in more rapid succession ( minor,

minor,  minor and

minor and  minor, to all of which the pedal

minor, to all of which the pedal  is consonant).

is consonant).

At reh. 6, a new motive, motive c occurs in a highly chromatic fugato which leads to the movement's second climax at reh. 8. Here, beneath an E/ tritone in the horns, one of Suk's favorite motives appears: the [0268] motive of death from Radúz and Mahulena (Example 6).

tritone in the horns, one of Suk's favorite motives appears: the [0268] motive of death from Radúz and Mahulena (Example 6).

Example 6: Death motive from Radúz and Mahulena.

This whole-tone motive c consisting of two pairs of tritones heralded the death of Radúz's father in that work. This "death" motive is transpositionally symmetrical: when transposed at the tritone (as it is in Asrael in the same measure in which it first appeared), it retains the same pitch classes. This motive c combines with the tritone in the horns to complete an entire whole-tone scale. In addition, the [026] harmonies of Ex. 2 can be seen as subsets of this collection. This emphasis on whole-tones contrasts with the Requiem semitone motive.

This section climaxes on an  augmented thirteenth chord two measures after reh. 8. This is followed by the return of the A section, whose characteristic pedal tone occurs a whole step higher than before. This "wrong" key is "corrected" at reh. 9. This recapitulation in

augmented thirteenth chord two measures after reh. 8. This is followed by the return of the A section, whose characteristic pedal tone occurs a whole step higher than before. This "wrong" key is "corrected" at reh. 9. This recapitulation in  is best understood in terms of the movement's drama: during the fugato, harmonic tension finally builds in a movement that has been harmonically static since its opening. This tension increases during the presentation of the "Death" motive. It appears that the opening motive a and accompanying pedal point have been affected by these musical events; either energized by them, or possibly thrown off track by their impact. One can liken this scenario to Suk's own life-journey, which was so dramatically affected by the deaths of both Dvořák and, shortly after this movement was completed, Suk's wife Otilka. This dramatic use of key is typical of this "second practice" of nineteenth century use of tonality, just as the tonal non-concentricity of the movement, which ends not in

is best understood in terms of the movement's drama: during the fugato, harmonic tension finally builds in a movement that has been harmonically static since its opening. This tension increases during the presentation of the "Death" motive. It appears that the opening motive a and accompanying pedal point have been affected by these musical events; either energized by them, or possibly thrown off track by their impact. One can liken this scenario to Suk's own life-journey, which was so dramatically affected by the deaths of both Dvořák and, shortly after this movement was completed, Suk's wife Otilka. This dramatic use of key is typical of this "second practice" of nineteenth century use of tonality, just as the tonal non-concentricity of the movement, which ends not in  , but in

, but in  minor.7

minor.7

As we have seen, the second movement of Asrael is short and relatively uncomplicated in its structure and development. While it serves as a great contrast to the colossal first movement, certain features bind the two together, such as the appearance of the Requiem and Death motives in various levels of composition.

A Summer's Tale: "Noon"

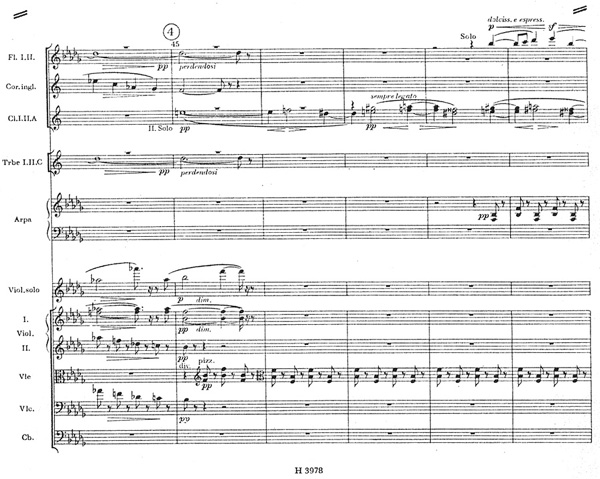

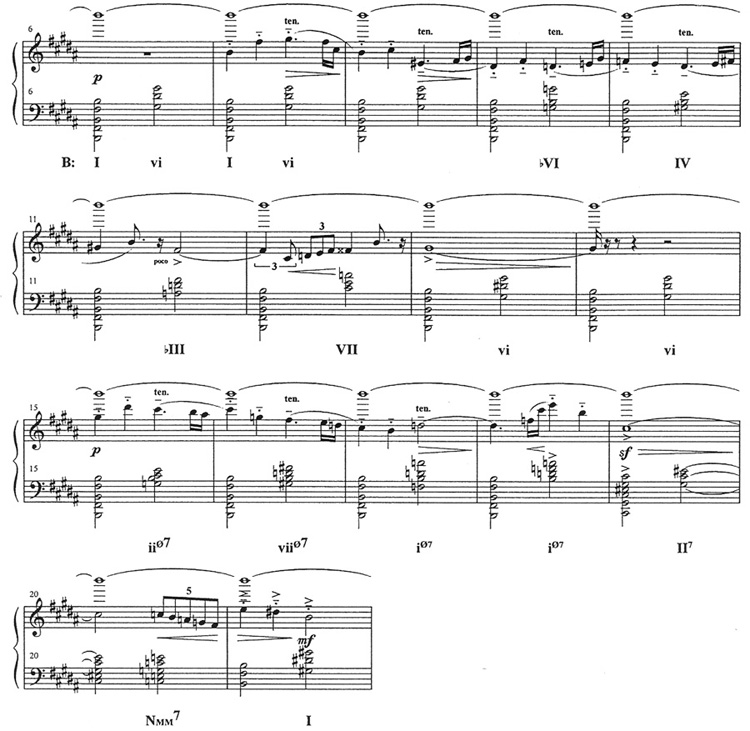

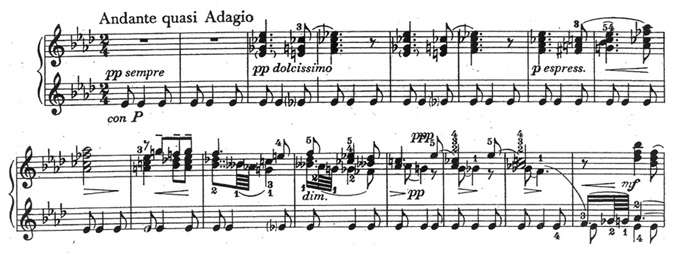

"Noon," from A Summer's Tale (1907-08), is, like the second movement of the Asrael symphony, the second and shortest movement of the work. Rather than a rondo, its form is ternary, with a very brief B section and a coda. Instead of being built around a dominant pedal, "Noon" is based primarily on a tonic pedal B above high C. The pitch might represent the intense and unrelenting sun high in the sky. As in the second movement of Asrael, Suk largely chooses harmonies to which the pedal tone is consonant. Example 7 is a piano reduction of mm. 6 through 20.

Example 7: Summer's Tale, ii, piano reduction, mm. 6-21.

To begin, beneath the B pedal we hear a gently undulating tonic and submediant whose ostinato is reminiscent of the alternating tonic and mediant harmonies of the third movement of Dvořák's American Suite. In m. 9, the harmony takes a new direction, visiting the chromatic mediants G major ( ) and D major (

) and D major ( ).

).

The central harmonies of this movement are derived from the opening melody which is played by the bass clarinet and doubled three octaves higher in the piccolo (mm. 7-14). The eighth note of the melody is our first chromatic note,  . Later, in m. 43, the enharmonic note F becomes the root of a dominant seventh chord that obscures the tonal center. Then, in the middle section of the movement, F major becomes a key center in its own right (m. 59). Another chromatic pitch in this melody,

. Later, in m. 43, the enharmonic note F becomes the root of a dominant seventh chord that obscures the tonal center. Then, in the middle section of the movement, F major becomes a key center in its own right (m. 59). Another chromatic pitch in this melody,  , recurs frequently in the form of a

, recurs frequently in the form of a  chord. In addition to both raised and lowered form of the fourth and fifth degrees, another important feature of this melody is its assumption of parallel keys: the tonic is equally B major and B minor, a characteristic we see in many of Suk's works, as well as in Czech music of the nineteenth century.8

chord. In addition to both raised and lowered form of the fourth and fifth degrees, another important feature of this melody is its assumption of parallel keys: the tonic is equally B major and B minor, a characteristic we see in many of Suk's works, as well as in Czech music of the nineteenth century.8

In the second phrase, which begins in m. 15 and continues to m. 20, the harmonic sequence becomes even further removed from a functional progression. Here, B is a member of all the chords of the sequence, which is generous in its share of half-diminished seventh chords. The third phrase extends all the way from m. 22 to m. 46; it contains a motive which is reminiscent of the crying dove motive of Dvořák's The Wood Dove, written only ten years earlier.  and

and  are prominent here, as well as the aforementioned F major as

are prominent here, as well as the aforementioned F major as  . F major becomes increasingly more prevalent and plays a leading role in blurring the tonality. By mm. 31-37, the tonality is suspended altogether by the alternation of two chords a tritone apart, G major and

. F major becomes increasingly more prevalent and plays a leading role in blurring the tonality. By mm. 31-37, the tonality is suspended altogether by the alternation of two chords a tritone apart, G major and  dominant seventh. When the later chord recurs in m. 40, it resolves in traditional deceptive resolution, up a semitone to D. At the end of the phrase, the key returns to B, yet since it resolves to an open fifth, the mode is equivocal.

dominant seventh. When the later chord recurs in m. 40, it resolves in traditional deceptive resolution, up a semitone to D. At the end of the phrase, the key returns to B, yet since it resolves to an open fifth, the mode is equivocal.

In summarizing our findings concerning the harmony of the first section of "Noon," we have seen Suk's tendency at first to employ both diatonic and chromatic chords to which the pedal tone B is consonant. At the beginning, submediant harmony is emphasized. As the melody and harmony grow more chromatic, the tonality becomes altogether suspended. In addition, we have noted that Suk anticipates his chromatic harmonies with chromatic melody notes, a compositional feature that is often associated with masters of tonal composition.9

Although the middle section (m. 52-62) is contrasting in texture, harmonically, it appears to be a review of the A section, due to its emphasis on  ,

,  and

and  . At the Moderato, m. 59, there is a modulation to the tritone-related key of F. This varied repetition brings to mind the repetition process in the slow movement of Asrael.

. At the Moderato, m. 59, there is a modulation to the tritone-related key of F. This varied repetition brings to mind the repetition process in the slow movement of Asrael.

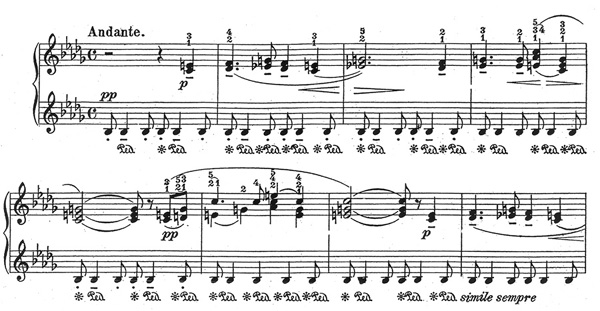

About Mother

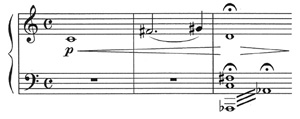

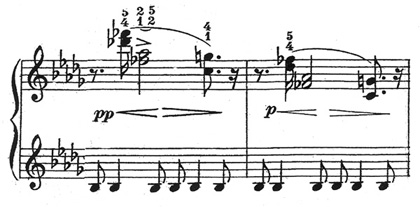

About Mother was the first piano composition Suk wrote in his third period, having composed Asrael the year before. It is a set of five impressions of his late beloved wife Otilka and bears the dedication: "Simple compositions for my son." "How Mother Sang at Night to the Sick Child" is the central movement of the suite, as well as the most popular. In addition, it is the only piece in the suite which approaches the simplicity indicated in the sub-title. The opening seven measures are seen in Example 8.

Example 8: "How Mother Sang at Night to the Sick Child" from About Mother, mm. 1-8.

The "tonic" chord seems to be a C dominant seventh chord in third inversion, as this sonority opens and closes the movement and ends most of the phrases. C Phrygian is the principal scale, with the third alternating between major and minor. The key signature, however, has five flats. The modal key signature for C Phrygian should contain only four flats. Indeed, the G flatted by the signature is consistently made natural in the A section of the work. It appears that Suk used this signature for two reasons. First, the signature of  minor points to the reiterated

minor points to the reiterated  , the central pitch of the movement, which remains constant throughout. The first emphasized harmony, which occurs at the downbeat of m. 2, is

, the central pitch of the movement, which remains constant throughout. The first emphasized harmony, which occurs at the downbeat of m. 2, is  minor. Second, the five-flat signature represents a tonal compromise: the B sections do seem to be in

minor. Second, the five-flat signature represents a tonal compromise: the B sections do seem to be in  minor. The form is a binary ABAB, with the A sections emphasizing the C dominant seventh chord, while the B sections emphasize the tritone-related

minor. The form is a binary ABAB, with the A sections emphasizing the C dominant seventh chord, while the B sections emphasize the tritone-related  major. A tritone goal was seen also in "Noon"; Suk typically reserves the motion of a tritone relation for a key moment.10

major. A tritone goal was seen also in "Noon"; Suk typically reserves the motion of a tritone relation for a key moment.10

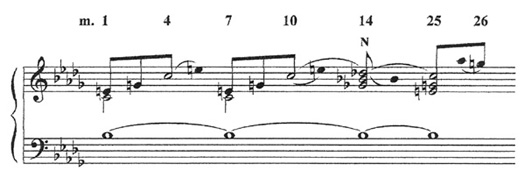

"How Mother Sang" lends itself to reduction, even though it does not contain a traditional Ursatz (Example 9).

Example 9: "How Mother Sang at Night," reduction, mm. 1-26.

Melodically, the A section is an embellishment of an unfolding C major arpeggio, which is repeated at measures 7-13. In the B sections, the note  supported by

supported by  harmony is understood as a structural upper neighbor to the note C of the A section. The neighbor resolves back to C in m. 25, and correspondingly in the second B section in m. 53. Although the lack of Urlinie descent gives the movement its still, dormant quality, the mild dissonance of the central dominant seventh chord in third inversion imbues the movement with harmonic suspense.

harmony is understood as a structural upper neighbor to the note C of the A section. The neighbor resolves back to C in m. 25, and correspondingly in the second B section in m. 53. Although the lack of Urlinie descent gives the movement its still, dormant quality, the mild dissonance of the central dominant seventh chord in third inversion imbues the movement with harmonic suspense.

Among Suk's ostinato movements, "How Mother Sang" is the only one whose reiterated tone represents neither tonic nor dominant of the primary chord. However, the tone briefly serves consecutively as the root of a  minor chord (at the downbeat of m. 2) and the fifth of an

minor chord (at the downbeat of m. 2) and the fifth of an  major chord (at the downbeat of m. 3). These consonant statements are fleeting. More structural is the note

major chord (at the downbeat of m. 3). These consonant statements are fleeting. More structural is the note  which serves as the third of the

which serves as the third of the  major chord at the beginning of the B section (m. 14). The irony of this miniature piece is that the note

major chord at the beginning of the B section (m. 14). The irony of this miniature piece is that the note  takes turns being the root, fifth and third of a harmony, but is only at rest when it is the seventh!

takes turns being the root, fifth and third of a harmony, but is only at rest when it is the seventh!

The impression painted is vivid: the repeated  undulation resembles the mother rocking her child, either in her arms or in a crib. The tone is as steady and fundamental as a heartbeat. Each melodic phrase rises and falls gently. These arches echo the rocking motion, yet on a different musical plane. The chord on which the music's motion repeatedly comes to rest is gently dissonant (C dominant seventh), yet we hear it as relatively stable. This chord may remind us that the child is indeed ill, and there can be no rest for the mother as long as it is in this state. Thus she rocks it through the night. In the end, the child has not yet recovered, yet is comforted by the mother's rocking, her song, and by her heartbeat which represents her love for the child.

undulation resembles the mother rocking her child, either in her arms or in a crib. The tone is as steady and fundamental as a heartbeat. Each melodic phrase rises and falls gently. These arches echo the rocking motion, yet on a different musical plane. The chord on which the music's motion repeatedly comes to rest is gently dissonant (C dominant seventh), yet we hear it as relatively stable. This chord may remind us that the child is indeed ill, and there can be no rest for the mother as long as it is in this state. Thus she rocks it through the night. In the end, the child has not yet recovered, yet is comforted by the mother's rocking, her song, and by her heartbeat which represents her love for the child.

The motive in Example 10 that closes the B section both times (mm. 26-27 and 54-55), which Filipovský calls "painful sighs," comes from Radúz and Mahulena.11

Example 10: "How Mother Sang at Night," mm. 26-27.

The return of A (m. 30) features new harmonic layers in fifths that grow and wane underneath the ostinato note. These fifths suggest the resonance of a bell with its overtones. The  -F fifth supports and brings forward the

-F fifth supports and brings forward the  ostinato pitch while compounding the section's harmonies. What used to be an

ostinato pitch while compounding the section's harmonies. What used to be an  major chord in m. 3 becomes a partly quartal chord (F-

major chord in m. 3 becomes a partly quartal chord (F- -

- -G) in m. 31, and a largely quintal chord

-G) in m. 31, and a largely quintal chord  -F-C-(E)-G in m. 33. This added layer can be considered an area of bitonality in the work, with the key of

-F-C-(E)-G in m. 33. This added layer can be considered an area of bitonality in the work, with the key of  major emphasized in the lower registers and C Phrygian above.

major emphasized in the lower registers and C Phrygian above.

The following piece in About Mother, "About Mother's Heart," is also based around an ostinato pedal point. It begins with an  in octaves, but unlike the gentle undulations of the previous piece, the rhythm here is irregular, alternating between triple, quadruple and quintuple divisions of the beat. The key signature of

in octaves, but unlike the gentle undulations of the previous piece, the rhythm here is irregular, alternating between triple, quadruple and quintuple divisions of the beat. The key signature of  major is indicative of the tonal center, but not of the minor mode which begins the piece. The lack of any progression that is diatonic to either

major is indicative of the tonal center, but not of the minor mode which begins the piece. The lack of any progression that is diatonic to either  major or minor, as well as the prolonged exploration of distant keys render the tonality suspended throughout most of the piece. The opening progression in

major or minor, as well as the prolonged exploration of distant keys render the tonality suspended throughout most of the piece. The opening progression in  minor: i -

minor: i -  - i, gives an early taste of the tonally non-functional progressions to come. The mode becomes major in m. 5.

- i, gives an early taste of the tonally non-functional progressions to come. The mode becomes major in m. 5.

Suk's harmonic strategy for the opening third of the movement (Example 11) is to center the ostinato pitch consonantly within a great number of chords while avoiding using it as tonic.

Example 11: "About Mother's Heart" from About Mother, reduction, mm. 1-13.

To begin, he has the  serve as the fifth of a key in both major and minor modes (m. 1-5). Then he moves in turn to all chords which can employ the

serve as the fifth of a key in both major and minor modes (m. 1-5). Then he moves in turn to all chords which can employ the  as the third beginning at m. 6 with an

as the third beginning at m. 6 with an  major chord. To elicit affect, he alters the chord to minor, even though this motion requires flatting the ostinato tone (m.7, E minor). He returns the pitch to

major chord. To elicit affect, he alters the chord to minor, even though this motion requires flatting the ostinato tone (m.7, E minor). He returns the pitch to  , and has it serve as third of a minor chord (m. 8, F minor.) This chord is altered to F major, thus moving the ostinato up to the note A in m. 12. While the ostinato is in this raised position, it serves as the root for the first time (m. 13, A major, enharmonic to

, and has it serve as third of a minor chord (m. 8, F minor.) This chord is altered to F major, thus moving the ostinato up to the note A in m. 12. While the ostinato is in this raised position, it serves as the root for the first time (m. 13, A major, enharmonic to  ) before returning both the ostinato and harmony to the opening chord. In addition to the chords mentioned, Suk employs half-diminished chords in mm. 7 and 9 in order to smoothen the voice leading. Throughout the passage the dynamic level gradually increases from piano to fortissimo.

) before returning both the ostinato and harmony to the opening chord. In addition to the chords mentioned, Suk employs half-diminished chords in mm. 7 and 9 in order to smoothen the voice leading. Throughout the passage the dynamic level gradually increases from piano to fortissimo.

Although the foregoing chord progression is not functional, it possesses five characteristics that are fundamental to Suk's harmonic language. First is the linking of parallel major and minor keys within a universal chromatic key. This characteristic of nineteenth-century music reaches its apotheosis in the musical styles such as Suk's where not only are  minor and

minor and  major juxtaposed, but also

major juxtaposed, but also  major and

major and  minor, as well as F minor and F major. Second is the sensitivity Suk shows to dissonance and consonance: the ostinato tone is always consonant in the opening segment of the piece. In the previous examples except "How Mother Sang," whenever the ostinato became dissonant, it was resolved. Third is Suk's interest in chromatic mediant relationships. We see this in the move from

minor, as well as F minor and F major. Second is the sensitivity Suk shows to dissonance and consonance: the ostinato tone is always consonant in the opening segment of the piece. In the previous examples except "How Mother Sang," whenever the ostinato became dissonant, it was resolved. Third is Suk's interest in chromatic mediant relationships. We see this in the move from  to

to  major, from

major, from  minor to F minor, and from F to A major.

minor to F minor, and from F to A major.

The fourth characteristic, found in some of Suk's pedal ostinato compositions, is the yielding or inflecting of the ostinato tone, usually for a programmatic reason. In "About Mother's Heart," we not only hear the submediant in m. 6; we also hear its minor version in m. 7. The chromatic change in the pedal tone reflects the unsteadiness of mother's heart. The final characteristic is one we have yet to discuss: when one studies the pitch classes which comprise these harmonies abstractly away from their registers, one sees the parsimony evident in the voice leading between each chord: in most cases there is either half-step motion or no motion at all between chords.

The next segment of music involves harmonies further removed from the key realm of  Major/minor (Example 12).

Major/minor (Example 12).

Example 12: "About Mother's Heart," mm. 14-21.

Measure 14 begins in the enharmonic key of  minor. The ostinato

minor. The ostinato  briefly becomes the seventh of a

briefly becomes the seventh of a  dominant seventh chord (m. 16) before appearing as the root of an

dominant seventh chord (m. 16) before appearing as the root of an  minor chord. The next harmonic motion is a tritone away, to the chord of D major (m. 17). Whether one hears this as the Neapolitan in

minor chord. The next harmonic motion is a tritone away, to the chord of D major (m. 17). Whether one hears this as the Neapolitan in  minor or simply as a motion within a suspended group of harmonies, the drop of the tritone in the bass combines with the first real appearance of the ostinato tone as a dissonance to highlight this chord for the listener. In the following chord, the ostinato, in an attempt to regain consonance, moves up to A natural with the seeming effort of a drowning person who is attempting to catch a breath of air at the water's surface. Then, the ostinato becomes disengaged within a chromatic scale as the harmony moves through another tritone from G minor to the home key of

minor or simply as a motion within a suspended group of harmonies, the drop of the tritone in the bass combines with the first real appearance of the ostinato tone as a dissonance to highlight this chord for the listener. In the following chord, the ostinato, in an attempt to regain consonance, moves up to A natural with the seeming effort of a drowning person who is attempting to catch a breath of air at the water's surface. Then, the ostinato becomes disengaged within a chromatic scale as the harmony moves through another tritone from G minor to the home key of  major. We have already noted that Suk's pairing of two tritones connoted death in earlier pieces. Through this double tritone motive, Suk intimates that Otilka's heart condition will lead to her death.

major. We have already noted that Suk's pairing of two tritones connoted death in earlier pieces. Through this double tritone motive, Suk intimates that Otilka's heart condition will lead to her death.

The middle section of "About Mother's Heart" (not shown), in the contrasting meter of 3/4, seems to explore a different aspect of mother, as it does not contain the incessant heartbeat. Although the passage is more lyrical, it proves to be another harmonic sojourn of a tritone: from  major in m. 24 to G major in m. 34. The recapitulation at m. 37 is unsettling, as the opening passage returns a minor second lower. This is "corrected" in m. 42, with the motion in the ostinato moving back to

major in m. 24 to G major in m. 34. The recapitulation at m. 37 is unsettling, as the opening passage returns a minor second lower. This is "corrected" in m. 42, with the motion in the ostinato moving back to  from G. In the coda (m. 52), the ostinato leaps down to the tonic

from G. In the coda (m. 52), the ostinato leaps down to the tonic  . Beneath it, the death motive from Radúz is heard plainly, confirming the meaning of the tritones heard earlier. In m. 55, the harmony moves a tritone again to G major. Just as

. Beneath it, the death motive from Radúz is heard plainly, confirming the meaning of the tritones heard earlier. In m. 55, the harmony moves a tritone again to G major. Just as  minor was paired with

minor was paired with  major, so does G minor follow G major. The return to

major, so does G minor follow G major. The return to  minor in m. 59 is jolting and final, connoting a death that is shocking and premature.

minor in m. 59 is jolting and final, connoting a death that is shocking and premature.

Conclusion: The "Self-Parody"

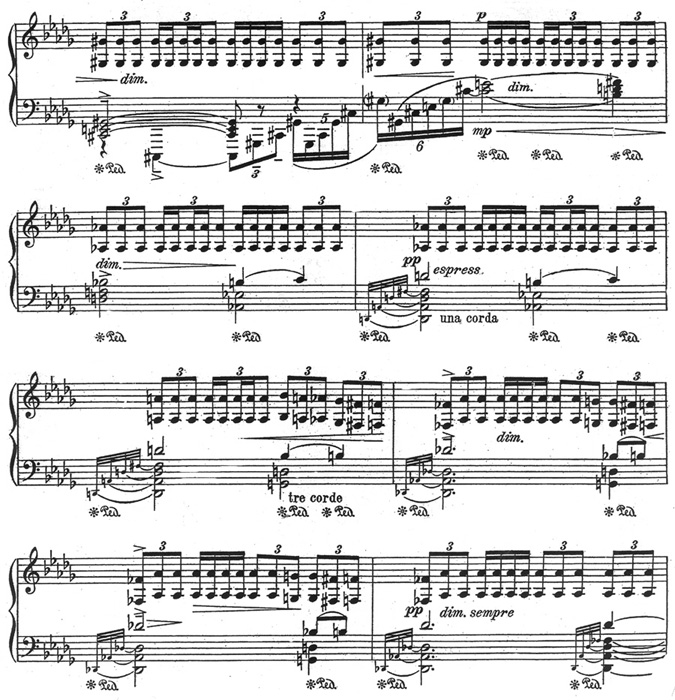

After having examined four examples of Suk's ostinato compositions, we are now prepared to understand to what degree Suk's little lullaby is truly a "Self-Parody." Although Suk includes this work as the third piece in his set of six Lullabies (op.33), it was first intended as part of a collective effort. In the spring of 1912, Jaroslav Křička proposed that each member of the Prague music club known as the Podskalská Philharmonic Society write one variation on the popular song "I Loved but Once in My Life" [Milovala jsem, ale jen jednou v životě svém], (Example 13).12

Example 13: "I Loved But Once in My Life."

The fact that Suk was asked to compose a piano variation in the form of a lullaby might attest to the popularity of his "How Mother Sang at Night to the Sick Child." The ostinato rhythm of the two pieces is identical. Among the other variations composed was a song by another important Dvořák pupil, Vitězslav Novák, which he wrote in the style of a Slovak folksong.

Suk composed his variation on 30 April 1912 and entitled it "Lullaby on a Popular Prague Street Song." The only modern edition of the lullaby, published by Supraphon, unfortunately does not give Suk's original subtitle, the indication "without inner necessity, but with manner." The Czech musicologist and critic Zdeněk Nejedly (1878-1962) believed that the only true school of Czech composition was rooted in Bedřich Smetana, and therefore the path of Dvořák and his students was musically invalid. In articles for Hudební Revue, Nejedly condemned Suk's music as "mannered" and "without internal necessity."13 Suk's appropriation of Nejedly's vindictive remark is an inside joke directed not only at Nejedly, but to four of Nejedly's associates to whom the lullaby was initially dedicated, including the composer Otakar Zich and the aesthetician Vladimír Helfert. In that same year, Suk included the Self-Parody in a collection of Six Lullabies for Piano, op. 33. He also changed the piece's dedication, making it to the Philharmonic Society itself.

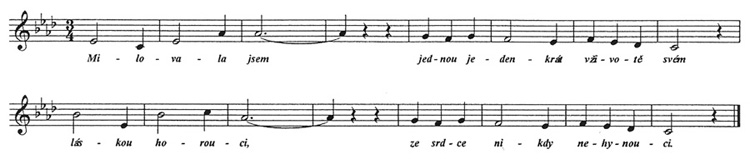

The first 16 measures of the Self-Parody are seen in Example 14.

Example 14: "Sentimental Self-Parody on a Street Song," mm. 1-16.

The melody from the song begins in m. 7. Since the piece is intended as a parody, we should expect to find in it Suk's stylistic traits in a concentrated or augmented form. The first of these traits is the already-mentioned ostinato pedal. The second is the free use of parallel modes: the key is as much A minor as A major; however, the piece has a floating harmonic quality due to the fact that the tonic chord always appears in second inversion. (Janáček frequently used this technique also.14) The third trait is non-functional harmony: although only one key center is suggested, the harmonies are chromatic and tonally vague. At the start, the tonal center is ambiguous due to the odd progression:  -

-  - vio7. A fourth trait of Suk is the parsimonious voice leading: the tenor line especially creeps in half steps. The half steps in mm. 9 and 10 recall the "painful sighs" of About Mother and Radúz. The pervasive half-step feature informs the harmony as well: to close the first phrase, Suk employs a Neapolitan leading to I (mm. 12-13) in place of an authentic cadence. Finally, Suk parodies his own harmonic proclivities as he emphasizes two of his favorite types of chord relationships: chromatic mediants (here to A, such as the

- vio7. A fourth trait of Suk is the parsimonious voice leading: the tenor line especially creeps in half steps. The half steps in mm. 9 and 10 recall the "painful sighs" of About Mother and Radúz. The pervasive half-step feature informs the harmony as well: to close the first phrase, Suk employs a Neapolitan leading to I (mm. 12-13) in place of an authentic cadence. Finally, Suk parodies his own harmonic proclivities as he emphasizes two of his favorite types of chord relationships: chromatic mediants (here to A, such as the  at m. 3 and the F at m. 9), and non-leading-tone half-diminished chords (in mm. 4, 7 and 9). The rest of the piece comprises repetitions of the first 18 measures with slight variations.

at m. 3 and the F at m. 9), and non-leading-tone half-diminished chords (in mm. 4, 7 and 9). The rest of the piece comprises repetitions of the first 18 measures with slight variations.

Suk's musical language represents an expansion of late nineteenth century chromatic tonal practice in terms of its chromatic linear and harmonic orientations, both of which supersede any functional progression. At the same time, it is tied to classical tradition through its rigorous motivic practice which it applies to multiple levels of composition. Moreover, it is melodically and rhythmically compelling. Although Suk's use of dissonance became increasingly freer throughout his career, he always maintained the importance of consonant resolution. In terms of color, Suk could hardly have done better than to have studied orchestration with Dvořák. Moreover, the timbres and textures of his piano music surpass those of the piano works of his teacher. Thus, there is little wonder why Suk's music is more popular today than ever before. It is music that beckons to be understood as well as heard.

1John Tyrrell, "Josef Suk," The New Grove Encyclopedia of Music and Musicians, Vol. 18 (London: MacMillian, 1980): 352.

2J. M. Květ, Josef Suk (Prague: Nákladem České akademie věda a umění, 1936): 24.

3It is possible that Suk's predilection for the number five inspired Oldřich Filipovský to divide Suk's output into five distinct periods. Klavírní tvorba Josefa Suka [The Piano Works of Josef Suk] (Pilsen: Nakladatelství Theodor Mare v Plzni, 1947): 11-12.

4Suk quoted this motive even before Dvořák's death in the piano piece "Evening Mood" from the suite Summer Impressions (1902).

5See the slow movement of Dvořák's "New World" Symphony, which begins in E major, the parallel mode of the key of the first movement, but immediately modulates to  , the primary tonality of the second movement.

, the primary tonality of the second movement.

6Filipovský, Oldřich, Klavírní tvorba Josefa Suka [The Piano Works of Josef Suk] (Plzeň: Nakladatelství Theodor Mare, 1947): 273. Two dissertations discuss motivic parallelism in the music of Janáček: Zdeněk Denny Skoumal, "Structure in the Late Instrumental Music of Leo Janáček" (Ph.D. dissertation, The City University of New York, 1992); John K. Novak, "The Programmatic Orchestral Works of Leo Janáček" (Ph.D. dissertation, The University of Texas at Austin, 1994).

7William Kinderman, Introduction to The Second Practice of Nineteenth-Century Tonality, edited by William Kinderman and Harold Krebs (Lincoln: The University of Nebraska Press, 1996): 10.

8Michael Beckerman, "In Search of Czechness in Music," 19th Century Music 10/1 (Summer 1986): 61-73.

9Patrick McCreless, "Syntagmatics and Paradigmatics: Some Implications for the Analysis of Chromaticism in Tonal Music," Music Theory Spectrum 14 (1991): 147-78.

10See the third two-part song of Op. 15 "Společenský hrob" [Common Grave] which progresses from  minor to C major.

minor to C major.

11Filipovský, 156.

12The song can be found in two collections: Vladimir Karbusický, Mezi lidové piseň a lager [Between Folk Song and Popular Song] (Prague: Supraphon, 1968): 140; and Josef Kotek, Dějiny české popularní hudby a zpěvu 19. a 20. stoleti [The History of Czech Popular Music and Song of the 19th and 20th Centuries], Vol. 1 (Prague: Academia, 1994): 118.

13I am indebted to Miroslav Nový, who explained to me the circumstances surrounding the original subtitle.

14John K. Novak, "Janáček's Nursery Rhymes as a Compendium of his Musical Style," College Music Symposium 37 (1999): 43-63.