Abstract

All undergraduates at Montana State University are required to generate a scholarly project and participate in a research/creative experience; however, the benefits of these research experiences for pre-service music teachers have not been explored. The purpose of this study was to examine recent music education graduates’ perceptions regarding their two required undergraduate research experiences, the Senior Capstone Project and the Teacher Work Sample, and to evaluate any impact these research experiences have on their current teaching. We asked practicing music teachers to reflect on their undergraduate research experiences regarding the two courses. Music teachers reported that participation in the research courses led them to be more likely to seek out research to enhance their own teaching, that they were better prepared to become active researchers, and that they could better interpret and use research data. The study also led to the following improvements in the delivery of undergraduate research: 1) better scaffolding of research skills prior to senior year; 2) having students choose topics relevant to future employment; 3) discussing the integration of teaching and research; and 4) emphasizing the practical applications of this type of learning.

Sadie is a vivacious elementary general music teacher who is currently completing her second year on the job. Her classroom is lively, she motivates learners to achieve at very high levels, and it is apparent that her students love her. Sadie attributes at least some of her success to research. “Research allows me to discover new techniques to try with students and helps me supplement lessons already in my repertoire. Research makes it easier for me to advocate for music in my school and in the lives of my students.”

There is mounting evidence regarding the benefits of undergraduate research-based learning, including increased student confidence, academic performance, engagement, and retention (Jenkins & Healey, 2010; Sadler & McKinney, 2010; Seymour, Hunter, Laursen, & Deantoni, 2004). Additional benefits specific to pre-service teachers include enhanced abilities to make informed instructional decisions, improved attitudes toward specific disciplinary content, and changes to the way pre-service teachers plan to teach in their future classrooms (Frager, 2010; Salter & Atkins, 2013). Research has also identified obstacles related to the implementation of undergraduate research. Dobozy (2011) suggested that challenges in undergraduate research are often connected to attitudinal barriers, including perceptions that research is irrelevant to teachers, that teachers lack skills to apply research, and that the application of research takes too much time.

In a partial response to the landmark report of the Boyer Commission on Educating Undergraduates in the Research University (1998), initiatives to incorporate undergraduate research in all content areas are underway. The number of universities that have comprehensive campus-wide undergraduate research programs has increased dramatically over the last decade, and the Council on Undergraduate Research has just received a robust response to its call for the new Awards for Undergraduate Research Activity (AURA). Campuses with long histories of undergraduate research have broadened their efforts, and most other campuses have developed programs rapidly. Among such campus-wide initiatives is the identification of pre-service teachers as target candidates for inclusion in programs that enable them to conduct research and promote their skills in interpreting and applying existing research (Kinkead, 2003).

Salter and Atkins (2013) suggested three potential strategies for involving pre-service teachers in undergraduate research experiences. First, students may join practicing researchers in their research. These experiences are typically powerful for pre-service teachers; however, the potential number of research opportunities necessary to meet student needs may be prohibitive. As a second option, pre-service teachers might experience research as a part of a methods course. Potential benefits of this strategy are improved attitudes and understandings of content; however, these experiences “often lack the necessary depth and intensity required to maintain these gains over time” (p. 160). To overcome these potential obstacles, Salter and Atkins recommend a dedicated undergraduate course that replicates authentic research for all pre-service teachers by incorporating small group investigations, whole-class discussions, and weekly written reflections on class activities.

Music teachers who understand and apply research to positively impact student learning will likely have enhanced pedagogies. By conducting research, they increase their efficiency and effectiveness as they face issues such as retention, diversity, the use of technology, and the effects of standardized testing and other curricular mandates. Accordingly, it is essential that all pre-service music education undergraduates have bona fide experiences with research. Participation in undergraduate research allows pre-service music teachers to interpret, conduct, and apply research in musical contexts.

All undergraduates at Montana State University are expected to generate a scholarly project and participate in a research/creative experience. Music education majors are required to participate in two undergraduate research experiences, the Senior Capstone Project and the Teacher Work Sample.

Senior Capstone Project

In the Montana State University School of Music, the senior capstone course centers on an independent research project on a topic chosen by the student with guidance from the professor. The class meets weekly in seminar format to discuss issues that apply to all, explore examples of successful projects, and review research methods. Students also arrange for individual weekly meetings with the professor, as needed. Various important scaffolding steps along the way include narrowing down topics, conducting literature searches, submitting an outline, discussing the project with classmates, soliciting additional mentor involvement, carrying out the research, and writing. Presentations to the class are mandatory, as is a written submission of the paper. Further dissemination of the research is encouraged, at the campus-wide Student Research Celebration, and beyond that, at national conferences such as the National Conference on Undergraduate Research (NCUR).

Teacher Work Sample

An assessment tool that is becoming increasingly popular in teacher education programs across the United States is the Teacher Work Sample (Dees, 2010). The Teacher Work Sample (TWS) was first developed at Western Oregon University during the 1980s as a way to allow pre-service teachers to develop a teaching unit, connect their teaching with student learning, and document their work (Benton, et al., 2012). The Teacher Work Sample is an assignment that demonstrates pre-service teachers’ ability to plan, deliver, assess, and reflect upon a standards-based instructional sequence. At Montana State University, the TWS has been required of all student teachers for the past 10 semesters. First, student teachers collect contextual data about their students and use that data to design an instructional unit and assessment plan, rooted in national and Common Core standards. Next, pre-service teachers implement the lesson sequence, demonstrate that they can modify and differentiate instruction, track and analyze assessment data, and reflect on results as they set goals for the future. Music education majors at Montana State University are required to complete two Teacher Work Samples, one at the primary level and one at the secondary level. Girod and Girod (2006) affirmed the TWS methodology as “a mechanism to examine teachers’ abilities to help all students learn” (p. 482); however, there is a lack of research regarding the effectiveness of the TWS methodology for undergraduate music education students.

Method

The purpose of this study was to examine recent music education graduates’ perceptions regarding their two required undergraduate research experiences, the Senior Capstone Project and the Teacher Work Sample, and to evaluate any impact these research experiences had on their teaching. We surveyed Montana State University School of Music alumni who had participated in these two required research experiences to evaluate the lasting effectiveness of these courses. Additionally, we sought the opportunity to improve and enhance our undergraduate research courses to better serve students. Our specific research questions were 1) how do recent music education graduates perceive their undergraduate research experiences, and 2) what impact did music education graduates’ undergraduate research experiences have on their teaching. The research questions guided the creation of the survey. Conway (2012) noted a lack of studies that directly addressed practicing teachers’ perceptions of their teacher education, and we anticipated that asking practicing music teachers to reflect on these undergraduate research experiences might provide unique insights regarding the value of those experiences, and how their involvement influenced their teaching.

We invited all 36 music education graduates between Spring 2010 and Fall 2014 of our university to participate in the study via an e-mail survey. Twenty-six graduates completed and returned the survey (72% response rate). Participants responded to a multiple-choice and open-response questionnaire designed to solicit reflections about their research experience, the benefits and challenges they perceived, and how their involvement in undergraduate research may have influenced their teaching. A music education specialist reviewed the survey before data collection and we edited the survey based on the feedback we received.

On the survey, we required a “yes” or “no” response to the following statement, “I am currently working/have worked as a music teacher.” We only included surveys with a “yes” response (n = 21) in the analysis of teaching practices and the influence of undergraduate research experiences on teaching. We analyzed all surveys (n = 26) on items that related to participants’ reflections of their undergraduate research experience and organized all open-response data into categories using qualitative methodology. Our initial steps in analyzing the data involved several repeated readings of the transcriptions of all open-ended survey responses. During these initial readings, we coded with a focus on benefits and challenges related to Senior Project and the Teacher Work Sample. Repeated readings aided in the identification of codes. We used Dedoose, a web-based qualitative data analysis program, to assist in the coding of all textual data. Seven main themes and 19 associated codes emerged from the survey data. The themes were 1) positive aspects, 2) challenges, and 3) influence of Senior Project; 4) positive aspects, 5) challenges, and 6) influence of the Teacher Work Sample; and 7) reflections about research.

Findings

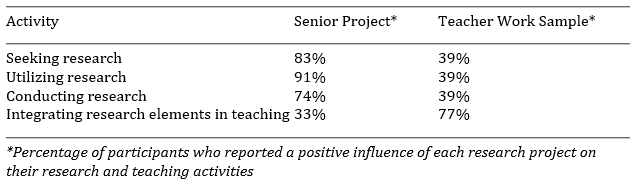

We first asked participants to identify which Senior Project elements were a part of their teaching and which elements they promoted for their students. They answered utilizing a simple yes/no framework, indicating first if they utilized each research element themselves, and second if they encouraged their own students to utilize that research element. We solicited follow-up written responses for each item, as well. Participants with teaching experience overwhelmingly agreed that they incorporated and promoted all the specific research elements on which Senior Project focused: inquiry based learning, creative process, current educational research, checking credibility of sources, and citing sources. In Figure 1, we display the percentage of participants with teaching experience who positively responded to each category related to Senior Project elements.

Figure 1. Incorporation of Senior Project Elements

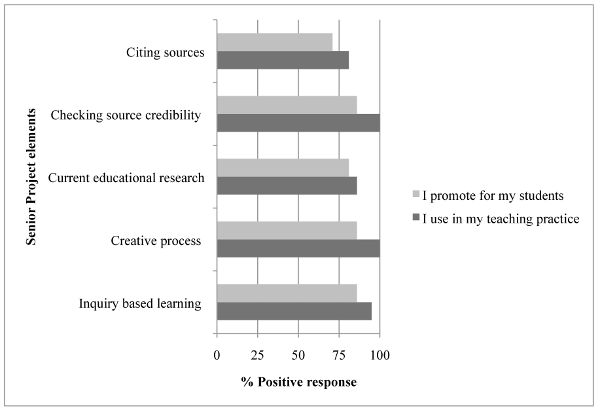

Similarly, we asked participants to identify which Teacher Work Sample elements were a part of their teaching and which elements they promoted for their students. Participants with teaching experience agreed that they incorporated and promoted the research elements on which the Teacher Work Sample project focused: the identification of contextual factors, planning that is informed by standards, the implementation of a plan, the measurement of progress, self-reflection, and the comparison of written pre- and post-test scores. In Figure 2, we display the percentage of participants with teaching experience who positively responded to each category related to Teacher Work Sample elements.

Figure 2. Incorporation of Teacher Work Sample Elements

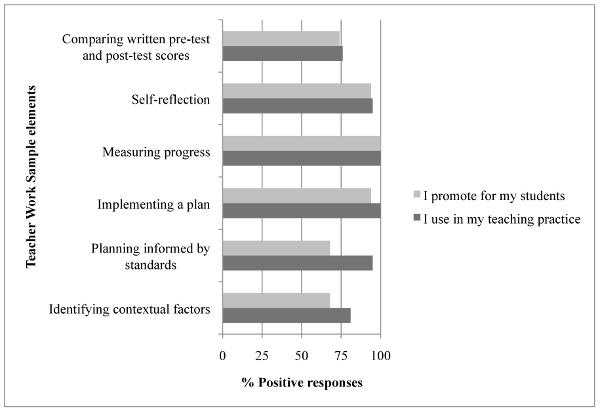

After asking about the elements of Senior Project and the Teacher Work Sample present in their teaching, we asked participants the extent that Senior Project and/or the Teacher Work Sample influenced their choices to incorporate those elements. We also solicited participant’s perceptions regarding the influence of their required undergraduate research courses on their current research activities. We display these data in Table 1.

Table 1. Influence of Research Projects on Research and Teaching Activities

Only 33% of participants indicated that Senior Project was an important factor in their decisions whether to integrate research elements in their teaching. Some participants completely discounted Senior Project with respect to influence on teaching practice. Josh’s response was typical of those participants’ comments. He stated, “[Senior Project was] not influential. The above elements are things that I would use in my teaching regardless of MUSI 499R.” Other participants gave a more balanced view. For example, Sadie said, “My undergraduate experience as a whole influenced my choice to incorporate the above [research] elements. I don't feel that Senior Project was the deciding factor for the above elements, but rather reinforced what I had already learned.” Ashley was one of the minority of participants who reported that Senior Project had a positive influence on her decision to incorporate elements such as inquiry based learning, the creative process, and current educational research in her teaching. Her response was emphatic, describing the influence as “Huge! I am so glad I had that class! My Senior Project really helped me implement these elements!”

In contrast, 77% of participants indicated that the completion of the Teacher Work Sample was an important factor in their decision about whether to integrate research elements in their teaching. For example, Katie stated, “The TWS gave me excellent practice in implementing these [research] elements into my teaching. Having written extensively about these elements, I feel more comfortable in employing them in my work.” Leah called the TWS “very influential,” stating, “All of my professional development goals have been in alignment with the TWS elements.” Some participants commented that their undergraduate experience as a whole was more influential than the TWS by itself. Gabrielle stated, “I feel like the Teacher Work Sample was a good way to keep me organized; however, my previous music education classes had me completely prepared. Those classes played the largest role in the incorporation of these elements into my teaching.” Mark was one of the minority of participants who did not report a positive influence of the TWS on his teaching. He stated, “I would have to say that the teacher work sample didn't really help me as a music teacher. Our lesson plans are rehearsals and we can't really plan ahead unless we know what needs to be rehearsed from the previous day.”

Although a majority of participants perceived that Senior Project was not an important factor in their decision whether to include research elements in their teaching, 74% of participants responded that Senior Project prepared them to become active researchers themselves, 83% responded that Senior Project prepared them to seek out research, and 91% responded that Senior Project prepared them to use research they encounter. Conversely, although a majority of participants perceived that the completion of a Teacher Work Sample was an important factor in their decisions whether to include research elements in their teaching, only 39% of participants responded that the TWS prepared them to become active researchers themselves, to seek out research, and to use research they encounter. Other experiences that students reported as important in preparing them to explore research included music methods classes, practicum experiences working with other teachers, and student teaching.

We designed a number of open-response survey questions to elicit participants’ perceptions about Senior Project and the Teacher Work Sample. For this set of questions, we did not supply any answers or alternatives from which participants could choose. We asked participants to describe 1) what they liked most about Senior Project; 2) what they would most like to improve about the Senior Project; 3) what they liked most about the Teacher Work Sample; and 4) what they would most like to improve about the Teacher Work Sample. We also invited participants to include additional comments about Senior Project and the Teacher Work Sample, if they wished.

Positive aspects of Senior Project

Participants’ comments about Senior Project were overwhelmingly positive. The most frequent was an expression of satisfaction with the depth of study. They appreciated the opportunity to “dedicate time to” and “dive into” their projects, with some also mentioning that they enjoyed the opportunity to collaborate closely with a professor. Many expressed that they appreciated the freedom to choose a topic that was personally meaningful, noting that they were “really passionate” about the topic they ultimately chose or that a particular topic was “close to my heart.” Beyond expressing overall satisfaction with the Senior Project process, a few acknowledged the effort required to complete the project: “In retrospect, I learned a great deal from the struggle...I would not change anything.”

Benefits of the Teacher Work Sample

Participants gave the Teacher Work Sample mixed reviews. Some identified a variety of positive features of the TWS, including practicality, the organized structure, and the way the assignment guidelines encouraged self-reflection. Participants’ most frequent responses were about the strong connection between the Teacher Work Sample and real-life teaching, emphasizing that the TWS helped them “understand [their] effectiveness as a teacher.” One participant called the TWS “the best way to learn.”

Challenges of Senior Project

In contrast to participants’ comments about the practicality of the Teacher Work Sample, the most frequently mentioned comment about Senior Project was that it lacked relevance to teaching. Many participants expressed regret that they hadn’t done projects “that would have helped me more in teaching” or that would were “more relevant to the skills needed to teach in Montana schools.” Participants also reported feeling unprepared for Senior Project, often in conjunction with a comment that it was difficult to choose a Senior Project topic. Some felt that the overall structure of the course seemed too loosely organized, at least from their perspective, commenting that they would have liked “more checkpoints” throughout the semester and “more standardized requirements.”

Challenges of the Teacher Work Sample

Participants identified several difficulties with the Teacher Work Sample. These difficulties included perceptions that the expectations were unrealistic, that the TWS was not applicable to music or was “busy-work,” and dissatisfaction with the requirement to complete two Teacher Work Samples during student teaching. Many were intensely critical of the TWS, calling it “frustrating and stressful,” “difficult to apply to the music classroom,” and “tedious.” When asked to describe the things that they liked most about the Teacher Work Sample, 24% reported there was nothing they liked. Conversely, when asked to describe the things that they would most like to change about the Teacher Work Sample, 19% reported they would not change a thing.

Conclusions/Recommendations

We acknowledge that our sample size was small and do not claim statistical representativeness or assert that our findings may be generalized to the entire population; however, that was not the intent of this study. Instead, the high response rate and our use of a defined population strengthened our evaluation of participants’ experience with two undergraduate research courses specific to our university. Additionally, given the current lack of research regarding undergraduate research experiences in education or music education, our conclusions regarding these courses contribute to this emerging conversation.

Most participants agreed that they incorporated and promoted the specific research elements that were the primary focus of both the Senior Project (inquiry based learning, creative process, current educational research, checking credibility of sources, and citing sources) and the Teacher Work Sample (the identification of contextual factors, planning that is informed by standards, the implementation of a plan, the measurement of progress, self-reflection, and the comparison of written pre- and post-test scores). This suggests at least some degree of lasting influence in participants’ two required undergraduate research courses. We recommend maintaining the current focus on research elements in Senior Project and the Teacher Work Sample.

While participants reported utilizing and promoting the research elements from their required undergraduate classes, their perceptions of the reasons for engaging in research activities and for incorporating research elements in their teaching were mixed. It appeared that Senior Project had a much greater influence on participants’ decisions to engage in research activities than the Teacher Work Sample. Conversely, the Teacher Work Sample appeared to have had a much greater influence on participants’ decisions to incorporate research elements in their teaching. These differences align with participants’ perceptions that Senior Project was a beneficial, in-depth research project that was not necessarily relevant to teaching, and that the Teacher Work Sample was strongly connected to real-life teaching, but lacked depth and true research emphasis.

Our evaluation of Senior Project and the Teacher Work Sample revealed some areas for improvement. We realize that to better prepare our students for their required independent research projects, we need to scaffold research skills earlier than senior year. Another major concern was the practical application of the projects. Participants often remarked that Senior Project lacked relevance to teaching. Additionally, some participants felt that the Teacher Work Sample was not applicable to music teachers, specifically. To address these concerns, we will encourage students to choose Senior Project topics that will be relevant to their future employment and discuss the integration of teaching and research. Going forward, only a single Teacher Work Sample will be required of all music education majors, a change due, in part, to the results of this study. This change to a single TWS will allow students to focus more intensely on one aspect of music education.

There is value in undergraduate research projects such as Senior Project and the Teacher Work Sample for future teachers. The overall structure of both courses was sound and our results highlighted aspects of each course that we will continue to emphasize in future semesters. A major strength of Senior Project is the scope of the projects students undertake. We plan to continue to promote in-depth studies. This aligns with participants’ comments that they appreciated the opportunity to choose a topic that had personal meaning and they valued the extended time allocated to their projects. One of the biggest advantages of the Teacher Work Sample is the strong connection between students’ projects and real-life teaching. We plan to continue to emphasize this practical aspect of the project. We will maintain the organizational structure of the Teacher Work Sample and preserve assignments that encourage self-reflection, as well.

Based on our results, we were able to make recommendations about our two required undergraduate courses for music education majors. It may be that some of our recommendations about the content and structure of research courses and projects for music education majors apply to other situations, as well. We believe that research courses are important for future teachers, in music and other fields and the implications for preparing teacher/scholars in this manner are compelling. We recommend that all teacher education programs include something like this pair of projects, at a minimum. It makes sense that teachers have a working knowledge of the process of discovery and analysis, so that they can not only use research in their teaching and their methods, but also so that they can enable their students to experience the excitement of the discovery of knowledge. This can have a lifelong impact on learners of all ages.

References

Benton, J. E., Powell, D., DeLine, M. A., Sautter, A., Talbut, M. H., Bratberg, W., & Cwick, S. (2012). The teacher work sample: A professional culminating activity that integrates general studies objectives. The Journal of General Education, 61(4), 369-387. doi: 10.1353/jge.2012.0032

Boyer Commission on Educating Undergraduates in the Research University. (1998). Reinventing Undergraduate Education: A Blueprint for America's Research Universities. (Report). Retrieved from http://www.niu.edu/engagedlearning/research/pdfs/Boyer_Report.pdf

Conway, C. M. (2012). Ten years later: Teachers reflect on “Perceptions of their beginning teachers, their mentors, and administrator regarding preservice music teacher preparation.” Journal of Research in Music Education, 60(3), 324-338. doi: 10.1177/0022429412453601

Dees, S. J. R. A. (2010). A qualitative study of the perceptions of the use of the teacher work sample methodology in student teaching (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database. (UMI No. 3488922)

Dobozy, E. (2011). Constrained by ideology: Attitudinal barriers to undergraduate research in Australian teacher education. (Report). e-Journal of Business Education and Scholarship Teaching, 5(2), 36-48.

Girod, M. & Girod, G. (2006). Exploring the efficacy of the Cook School District simulation. Journal of Teacher Education, 57(5), 481-497. doi: 10.1177/0022487106293742

Frager, A. M. (2010). Helping preservice reading teachers learn to read and conduct research to inform their instruction. Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy, 54(3), 199-208. doi: 10.1598/JAAL.54.3.5

Jenkins, A., & Healey, M. (2010). Undergraduate research and international initiatives to link teaching and research. Council on Undergraduate Research, 30(3), 36-42.

Kinkead, J. (2003). Learning through inquiry: An overview of undergraduate research. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 93, 5–18. doi: 10.1002/tl.85

Sadler, L., & McKinney, T. D. (2010). Scientific research for undergraduate students: A review of the literature. Journal of College Science Teaching, 39(5), 43-51.

Salter, I., & Atkins, L. (2013). Student-generated scientific inquiry for elementary education undergraduates: Course development, outcomes, and implications. Journal of Science Teacher Education, 24(1), 157-177. doi: 10.1007/s10972-011-9250-3

Seymour, E., Hunter, A.-B., Laursen, S. L., and Deantoni, T. (2004). Establishing the benefits of research experiences for undergraduates in the sciences: First findings from a three-year study. Science Education, 88(4), 493-534. doi: 10.1002/sce.10131