Introduction and Background

The history survey of Western art music is traditionally taught in a two- or three-course sequence in most undergraduate music degree programs in the United States. At The University of Texas Rio Grande Valley, this sequence consists of three courses: Music History I covers antiquity through the Baroque; Music History II spans the Enlightenment to around 1875; and Music History III, the turn of the twentieth century to the present. Course objectives for this sequence are threefold: to learn the historical, aesthetic, cultural and philosophical framework that lies at the heart of music history (context); to understand how that information relates to musical compositions (application); and to show an understanding of the appropriate methodological tools of scholarly inquiry through some type of research project (scholarship). And in a music history course, application means studying style characteristics in musical scores and hearing those characteristics within the music. All of these objectives must be met in order to achieve the overall goal of any music history course, which is to produce better musicians through a comprehensive understanding of musical style.

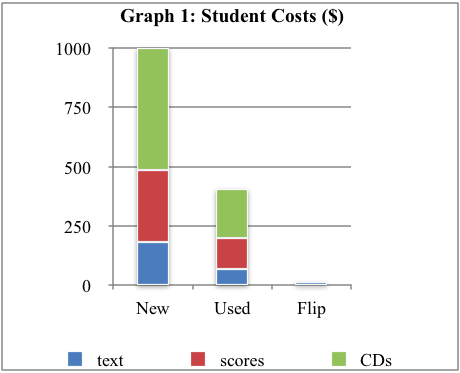

Traditionally, and perpetually, music history courses are taught primarily by strict lecture, supplemented by homework assignments of readings and/or musical score analysis.1 Baumer, Matthew (2015). A Snapshot of Music History Teaching to Undergraduate Music Majors, 2011-2012: Curricula, Methods, Assessment, and Objectives. Journal of Music History Pedagogy, 5(2), pp. 23-47 My frustration with this method of teaching is that class time is dominated by providing students with the context, leaving little time for practical application. Moreover, due to the current costs of textbooks, score anthologies and sets of recorded CDs or music streaming packages, classroom discussion and score study is often ineffective, as many students do not participate simply because they do not have the resources to purchase these materials, and are therefore unprepared for class. Leaving the important task of score study to students in homework assignments can also be ineffectual, as their work often tends to be unsatisfactory either because of a lack of guidance, motivation or effort.

Therefore, the current project involves “flipping,” so that the context is learned outside of class, by means of online video, readings and e-materials, and class time is then spent assessing student progress, and, more importantly, in application of the learned information through discussion and the study of musical scores. All of this is accomplished by means of iPad technology, as all of my students use iPads in both the online and in-class portions of these hybrid classes.

This teaching transformation began in the spring semester of 2013, when the university undertook an iPad Pilot Project, whereby several faculty members were issued iPads for themselves and their students in order to study the effects of this type of technology on the teaching and learning process. After training on the devices and apps in the spring, I spent the summer of 2013 preparing video lessons, assembling readings and other online materials, and designing in-class activities for the Music History III course. I decided to flip the course sequence in reverse order for two reasons. Since the third course in the sequence was not scheduled until the spring of 2014, it would give me enough time to make sure I had created a well-conceived pedagogical package. A second reason for flipping in reverse order is that it provided me with a natural cohort of students that had begun the sequence with the traditional method of instruction, and could therefore provide me with valuable data for comparison. In subsequent summers I flipped Music History II, and finally Music History I.

The Flipped Music History Class

Today, my music history classes are vibrant, engaging, noisy and dynamic, with students enthusiastically involved in learning activities during class, and yet still receiving the necessary contextual information, but on their own time. Outside of class, students watch video lessons based on slideshow presentations and receive all other class materials through Apple’s outstanding course delivery system iTunes U. In class, students engage in collaborative and project-based learning by dividing into groups to answer analytical questions about representative musical scores.

Online

Removing lectures from the classroom environment and making them available online is one of the main ingredients of today's flipped classroom.2 Bergmann, J., and Sams, A. Flip Your Classroom: Reach Every Student in Every Class Every Day. Eugene, OR, and Washington, D.C.: International Society for Technology in Education, 2012 There are many ways to do this. Some who have flipped their classrooms simply videotape their lectures, or create screencasts, and then post them online. Instead, I used my own pre-existing Keynote slideshows, recorded commentary as mp3 files, imbedded these files into the individual slides, and then saved the slideshows as QuickTime movies. This method of creating online lectures gives the instructor total control over the finished product, and also allows one to change part of a lesson without having to re-record the entire presentation. It is important to understand, however, that creating these types of lessons is more time consuming than simply recording a lecture. Because these video lessons are available on iTunes U, students can stream or download them to their iPads for viewing at any place and at any time of the day.

Study scores and audio files can similarly be placed in iTunes U for regular and repeated student access. Public domain musical scores, such as those from the Petrucci Music Library website, can be downloaded from iTunes U into a music reading app such as piaScore or forScore, where students can mark annotations, structural analyses, chordal analyses or other pertinent information. Likewise, audio files can be streamed directly to the iPad, and even downloaded to the iTunes U app for listening when WiFi is not available.

Incidentally, all audio files posted in iTunes U can only be accessed through the iTunes U app on the iPad (or any iOS device, including iPhone and iPod Touch), and cannot be downloaded or streamed to any other app. Therefore the music cannot be illegally shared or copied. And when the semester is over, these audio files are no longer accessible to students, unless they have purchased them through iTunes. In fact, when considering copyright issues, it may be helpful to understand that iTunes U features both public and private courses. When navigating through the iTunes U app on an iOS device one can freely access the many public courses available from universities and other educational institutions around the globe. However, iTunes U also hosts many, many more private courses that are available only to those with an enroll code, which Apple supplies to the instructors and students in a particular class. These courses are invisible to one who might be casually searching through iTunes U, however since they are closed to outsiders, they are no different from closed physical classrooms, except that they are digital. In this respect, they offer more protection with regard to the educational use of copyrighted material than public courses. The American Library Association has provided a comprehensive guide to copyright issues with regard to Fair Use and the TEACH Act for courses such as this.3Distance Education and the TEACH Act (n.d.). Retrieved from the American Library Association website: http://www.ala.org/advocacy/copyright/teachact

And then there are many, many additional materials that music history instructors commonly make available to their students. These may include study guides and tips, translations of vocal texts, book chapters, journal articles, opera librettos and synopses, films of operas, ballets or orchestral concerts, or even interviews with composers and performers. Traditionally, these materials would be placed on reserve in a university library, or made available for a small fee as a “professor packet” in a university bookstore. However, in this flipped music history class, all of these materials are conveniently placed in iTunes U and are available to the student on the iPad. This “one-stop-shop” aspect of iTunes U is one of the features that my students like best. Everything they need for their course is on the iPad, and resides in iTunes U.

In Class

Of course, the online portion of a flipped class is only half the story. Flipping also involves relocating traditional homework or active learning assignments to the classroom, where an instructor can monitor the learning process. Accordingly, my students engage in project-based and collaborative assignments, but also discussion and assessment, on a daily basis.

In my flipped music history classes, discussion of the prepared material takes place at the beginning of each session. I ask that each student come to class with at least two questions, and if they are hesitant to speak, I will randomly call on several to ask their questions. This will usually stimulate a short discussion, or at least a clarification of the prepared material. Next is a short assessment using an app called Socrative, which is offered in both teacher and student versions for the iPad. From the teacher app, an instructor can wirelessly send a short quiz to all of the students in a class, and then Socrative instantly scores the quiz. Furthermore, the teacher app shows real-time assessment, so the instructor can see at a glance which students probably did and did not adequately prepare for the class, and also which questions posed the most problems. This type of daily formative assessment is valuable on many levels, not the least of which is that the instructor will be alerted to a general misunderstanding of course material, and can address the problem immediately.

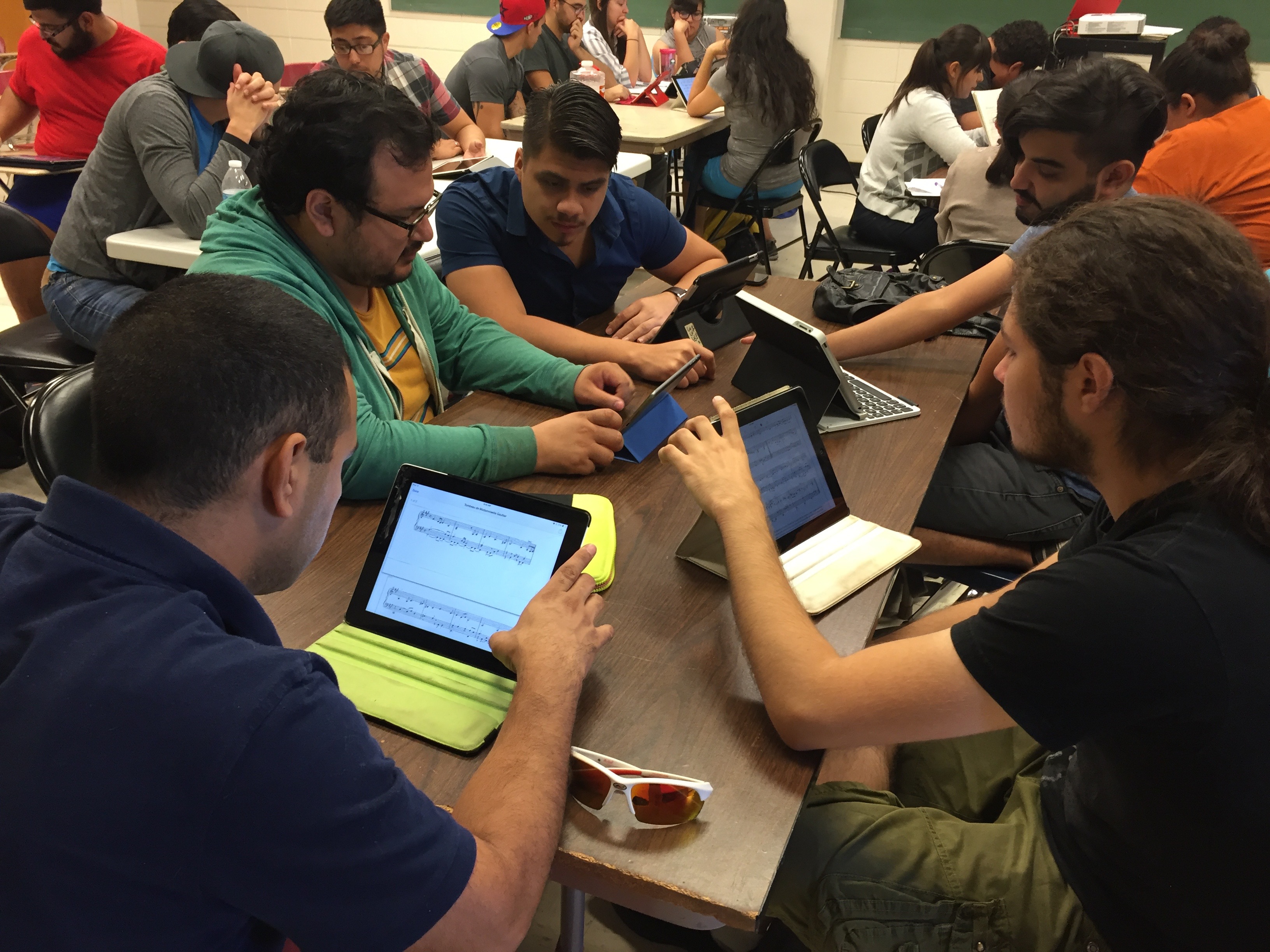

The majority of class time is spent analyzing musical scores appropriate to the topic of the day. I divide my classes into groups of four or five students and then pose a series of analytical questions to each (see Image 1).

Image 1 (above): “Team Mozart” working together on a set of analytical questions, with other teams in the background.

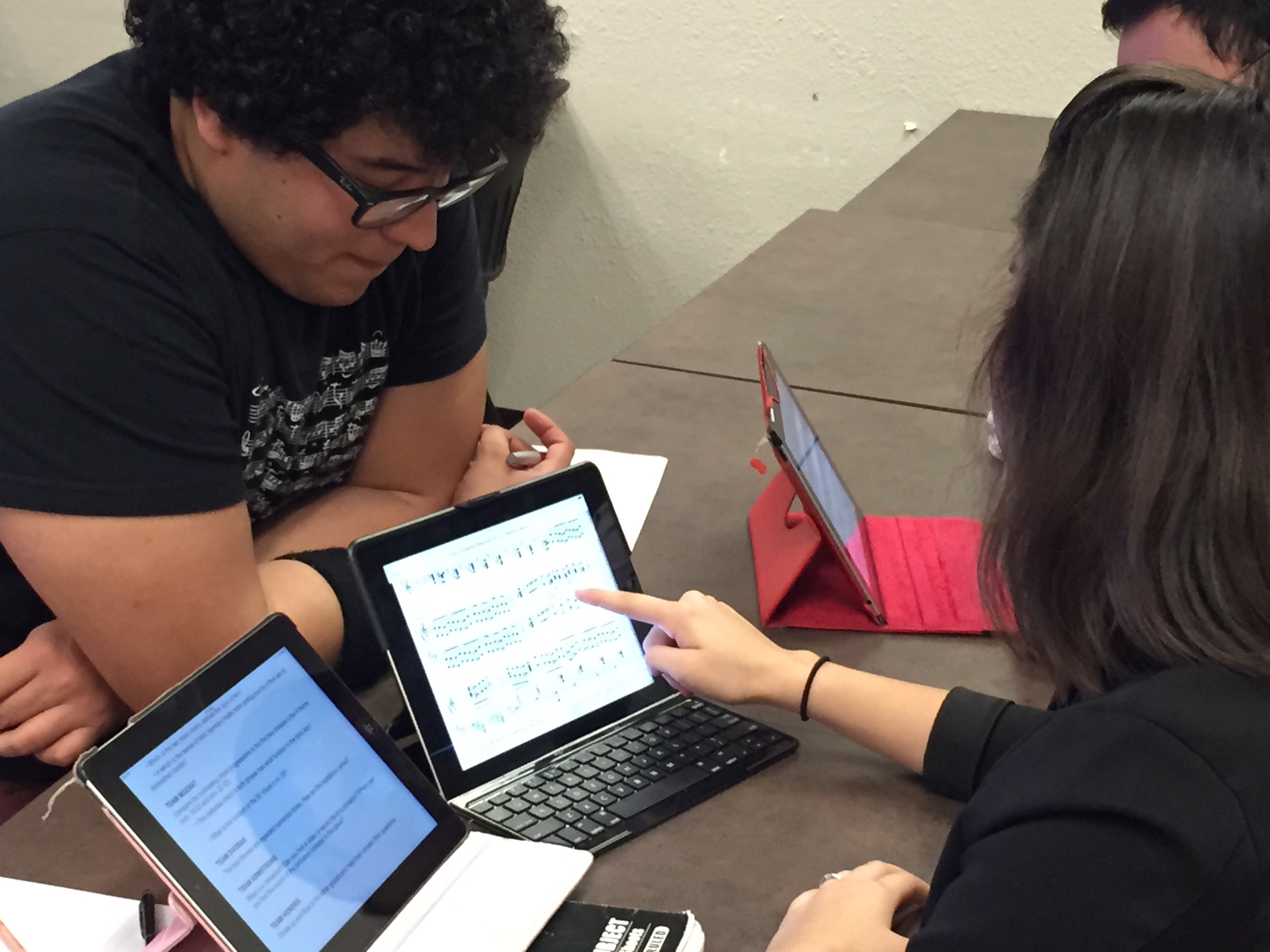

Before each class, students are requested to download the scores for the day into their music reading apps (piaScore or forScore). I prepare the analytical questions in advance and save them as PDF files in my iPad, and then in class I send the files wirelessly to the students’ iPads through AirDrop. At this point, the “teams,” begin to work by answering the questions and marking annotations in their scores (see Image 2).

Image 2 (above): This photo shows analytical questions on the left iPad, and a student writing her answers in the score on the right, in consultation with other students in her group.

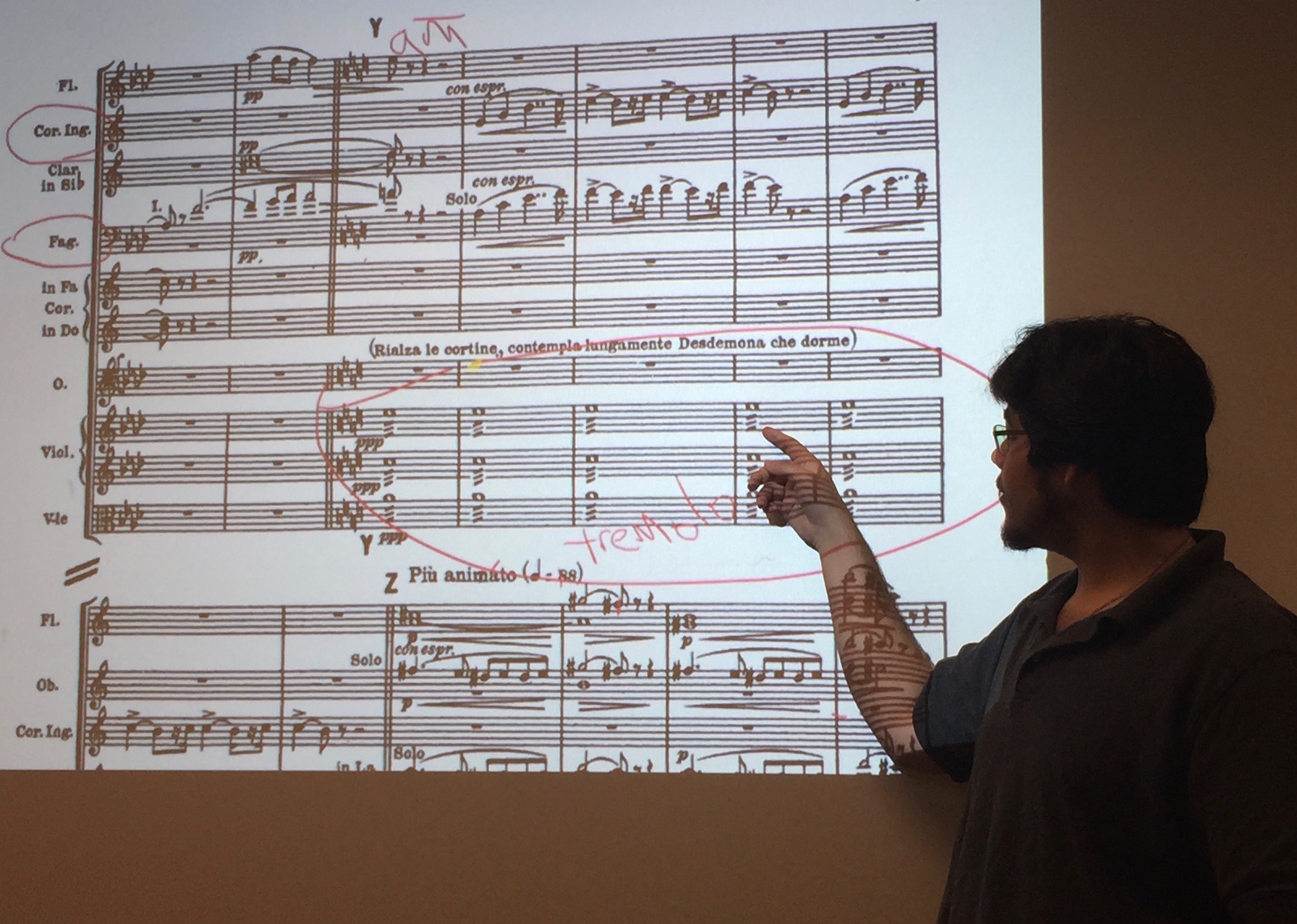

The attractiveness of this procedure is that the instructor is available to circulate from group to group, answering questions and guiding the process. Finally, each group makes a presentation to the class by projecting the annotated scores onto a large video screen by means of AppleTV and AirPlay (see Image 3). If time allows, the music can be played through classroom loudspeakers while an annotated score is displayed on the video screen.

Image 3 (above): This team spokesperson presents his group’s efforts to the class.

Why Flipped?

Placing course materials in iTunes U is a much more efficient method of content delivery because students can access them anywhere and at any time. My students consistently tell me in end-of-course questionnaires that this is the feature of the flipped class they like best. Students can also apply the learned information more effectively by studying scores in the classroom, with the instructor guiding the process and fellow team members available for collaboration. Furthermore, student engagement is one of the most important reasons for implementing a flipped class such as this. Here are some typical comments from my students concerning engagement:

I feel that the learning is more in my hands than it would be in a traditional lecture style class.

Very interesting, never boring, appealed to the three learning ways of seeing, hearing and physical interaction.

I seem to learn easier and gain a better understanding using technology. I was more engaged throughout the course than I ever had been.

I feel like with this new approach that I’m not just learning the information to pass the class. I feel like I will carry this information with me in the real world.

Honestly, when you told us the way the class was set up at the beginning of the semester, I thought this would be a nightmare. But I can honestly say this has been a great experience. This is (the) most I feel like I have learned in a music history class, or any history (class) for that matter.

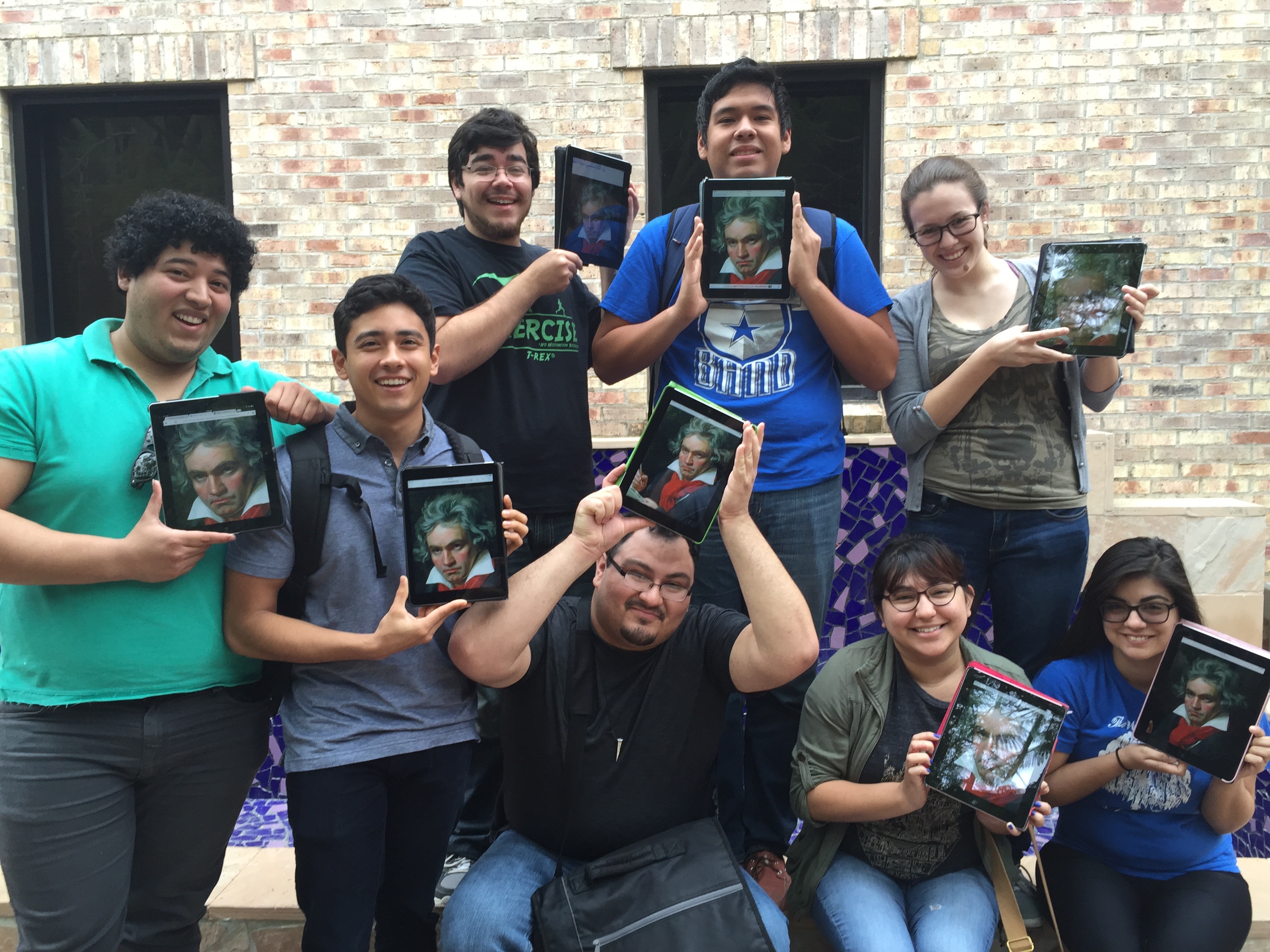

Thus far, only three students from a total of one-hundred and seventy have indicated they prefer the old method of classroom lecture, resulting in a student approval rating of almost 99%. And frankly, those three dissenting students were from my first two flipped classes. Each time I have taught this new method, I have made improvements to the approach based on personal experience and student feedback. In the last three class offerings, I received no indications that students would prefer another teaching method (see Image 4).

Image 4 (above): Music history students with their iPads.

In addition to efficient content delivery, effective score study, and student engagement, there are other positive outcomes from implementing a hybrid course such as this. First is the cost factor. Course materials in a music history class are usually quite expensive. There are three types of course materials that each student must have: a textbook, scores for study, and music for listening. Bar Graph 1 compares retail and pre-owned costs for these materials with the costs for my students in the flipped music history class.

One textbook covers the entire content of the sequence from the first course through the last. My chosen textbook costs $182 retail and around $70 used. Although one textbook will suffice for all three courses, students must purchase a separate score anthology for each course at about $100 each, for a retail total of $300 for the sequence. Likewise, students must purchase a different set of CDs for each course, for a total of over $500 retail cost. In sum, students must pay about $1000 retail (or over $400 used) for materials for the three-course sequence. However, because I can populate my lessons in iTunes U with up-to-date materials and can “push” new materials throughout the semester to my students, I don’t feel the need for them to purchase the most recent edition of the textbook. In fact, I encourage them to purchase earlier editions, which they can find online for less than fifteen dollars used. In addition, I post public domain musical scores and audio files on iTunes U for my students to download and stream to their iPads, at no cost. It should come as no surprise that this is also one of the most popular features of my flipped classes.

Finally, there is one unintentional, but attractive, consequence of this new method of teaching music history. These classes traditionally consume large amounts of paper, from the twelve-page syllabus on the first day of class to the multi-page research paper to the final exam. In the flipped music history class, I use absolutely no paper at all. Everything, from course materials to tests to written assignments, is accomplished digitally on the iPad.

A Recent Enhancement

In the past year, I have begun to more deeply explore the many and varied pedagogical uses of iPad technology in an attempt to further improve the learning experience for my students. A more recent, and particularly successful, enhancement to the course is a new approach to the research paper. When I moved to the flipped method of instruction, I continued to require research papers from my students, and although I asked them to submit their efforts digitally as Word, Pages or PDF files, the resulting works were still traditional term papers. Since my students were using iPads in all other aspects of the class, I began to wonder how I could use this device to make the process of researching, writing and especially the presentation of the term paper more engaging for the student and reader.

My search for the “next-generation” term paper led me to The Mozart Project, a multi-touch book available for purchase on the Apple iBooks Store. This book, written by several leading Mozart scholars including Cliff Eisen, Neal Zaslaw and John Irving, is a masterful blend of scholarship and design. The multi-touch experience greatly enhances the discovery process in a book such as this. Readers are able to access hyperlinks to information both within and independent of the book, parenthetical and footnote pop-ups, galleries, interactive time-lines, digital search features, and embedded audio and video. In describing the experience of an interactive book, the producers of The Mozart Project, James Fairclough and Harry Farnham, wrote: “Every curious need or direction can be satisfied and explored in ways which are limited only by imagination. With interactive books, the relationship between reader and content could become much more visceral and personal than ever before.”

Moreover, the availability of new and powerful software applications, like Apple’s iBooks Author, has allowed writers to make use of these interactive features without having to master programming. Again, from Fairclough and Farnham: “Suddenly we could become the builders of a book that was limitless in its potential without any of the programming hurdles or outlandish software costs.” If Fairclough and Farnham could put together a book such as The Mozart Project, why not me, or my students? In creating my own interactive book (see “A Final Word” below), I found that the process involved in creating an interactive book was straightforward and uncomplicated. After completing my book in the fall of 2015, I added a multi-touch book assignment to my Music History III class, in lieu of a traditional term paper, the very next semester. But unfortunately, my students could not use iBooks Author. Being a full-featured app, it can be used only on a Macintosh computer, not an iPad with its less-powerful processor. Therefore I began a search for an app that would allow students to create interactive books on the iPad, and my search led me to Book Creator.

Book Creator is a product of Red Jumper Limited, and while not as robust as iBooks Author, it still is capable of creating impressive, multi-touch books without difficulty and with little to no cost to the student. Indeed, my students can produce their first book for no charge with Book Creator, but afterward they must pay a fee of only $4.99 for all subsequent books. And while the app works beautifully on the iPad, it is not limited to that device. Book Creator is cross platform, and therefore available to users of Android, Windows and Apple.

The results of this experiment were quite encouraging. Students approached this assignment with an excitement and energy that I had never before seen for the traditional term paper. And although not all the books were of superior quality, I was happy with my students’ overall efforts and enthusiasm. From the books my students have now produced in two different courses, I am convinced that all music majors can benefit from such an assignment. Creating a book such as this compels the university music student to develop the skills of working with images, audio and video, in addition to the customary research and writing skills. And these are all skills that the future musician–either performer, educator or scholar–will need for twenty-first century jobs.

Results

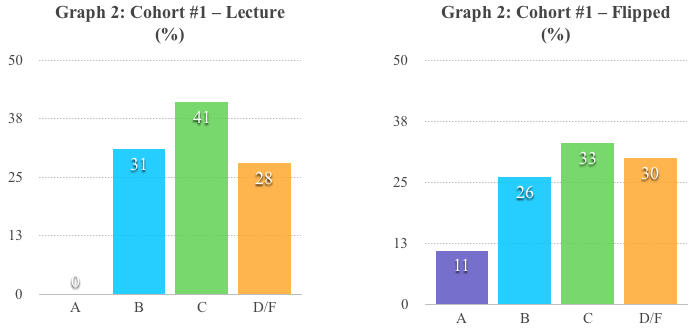

In order to create a fully hybrid course sequence, and because of the time involved in preparing online videos, I found it necessary to flip one class at a time. As mentioned above, I began by flipping Music History III first, and then proceeding backwards, flipping the first course in the sequence last. Because I created the hybrids in reverse order, I was able track several cohorts of students who began the sequence with the traditional lecture style, and yet ended the sequence with the flipped classes. Bar Graphs 2 and 3 show grade distributions for the first two of these cohorts, both lecture and flipped.

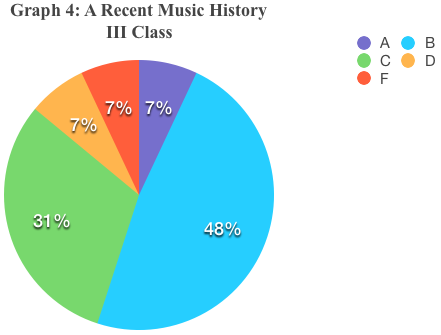

These charts show significant migration from the “C” category to the “B” and “A” categories, but not much movement in the “D/F” categories. One conclusion that may be drawn from this data is that the motivated student is able to rise to the next level with the flipped class. However, I was not pleased with the large number of unmotivated “D/F” students, and so I continued to make minor adjustments in each successive class based on my own perceptions and student suggestions. 4, a pie chart, shows a marked improvement in the “D/F” categories from a more recent Music History III class. More data is needed, and will continue to be collected over the next few years. Even so, while these preliminary results may be inconclusive, they are certainly encouraging.

A Final Word

In spite of the promising results shown above with regard to student performance, it must be understood that my principal reason for moving to a flipped-class approach was not to raise student grades, although that has certainly been a pleasant consequence. Rather, my primary motivation was to more fully engage my students.

Too often, students experience various degrees of boredom in the typical music history lecture class. They are often inattentive in class but will usually learn enough to pass the tests and assignments, yet will promptly forget most of it. And that is a pity, because the content is exciting, the music is compelling, and the knowledge is necessary for a successful career in music.

I encourage anyone who desires a higher level of engagement for their students to try this method of instruction. And, in order to help those who might be interested, I have written a guidebook for creating the type of hybrid music history course that has been described in this article. Teaching Music History with iPad is a multi-touch, interactive book available for free from the Apple iBooks Store.

If we, as teachers, can instill enthusiasm for the subject matter in our students, it just might produce in them a desire for knowledge, an excitement for discovery, and an eagerness to continue learning once the class has ended. With the flipped music history class, I am now beginning to experience this type of reaction in my students. While it is true that the initial preparation of a flipped class takes more time than usual, I have found the results to be well worth the effort.

Notes

1 Baumer, Matthew (2015). A Snapshot of Music History Teaching to Undergraduate Music Majors, 2011-2012: Curricula, Methods, Assessment, and Objectives. Journal of Music History Pedagogy, 5(2), pp. 23-47.

2 Bergmann, J., and Sams, A. Flip Your Classroom: Reach Every Student in Every Class Every Day. Eugene, OR, and Washington, D.C.: International Society for Technology in Education, 2012.

3 Distance Education and the TEACH Act (n.d.). Retrieved from the American Library Association website: http://www.ala.org/advocacy/copyright/teachact

Bibliography

Baumer, Matthew (2015). A Snapshot of Music History Teaching to Undergraduate Music Majors, 2011-2012: Curricula, Methods, Assessment, and Objectives. Journal of Music History Pedagogy, 5(2), pp. 23-47.

Bergmann, J., and Sams, A. Flip Your Classroom: Reach Every Student in Every Class Every Day. Eugene, OR, and Washington, D.C.: International Society for Technology in Education, 2012.

Brownlow, A. (2015). Teaching Music History with iPad. Retrieved from Apple iBooks Store: https://itunes.apple.com/us/book/teaching-music-history-with-ipad/id1050306740?mt=11

Eisen, C., Beales, D., Irving, J., Wallfisch, E., Feldman, D. H., Stafford, W., Zaslaw, N., Till, N., Keefe, S. (2015). The Mozart Project. Retrieved from Apple iBooks Store: https://itunes.apple.com/us/book/the-mozart-project/id844639558?mt=11

Petrucci Music Library (n.d.). Retrieved from the International Music Score Library Project website: http://imslp.org/wiki/Main_Page

Sales, A. (2016). Multi-Touch Books in Higher Education. Retrieved from Apple iBooks Store: https://itunes.apple.com/us/book/multi-touch-books-in-higher-education/id1159709140?mt=11