ABSTRACT

This article analyses two pieces by Colombian composer Juan Antonio Cuéllar. The first piece, Pieza para Violín Solo (Piece for Violin Solo), is a short piece using centered pitch harmonic motions. Pieza para Violín Solo is based on porro, a folk dance from the Caribbean region of Colombia. The second piece is trio Conversations for violin, cello, and piano, written as a theme and variations. Cuéllar transformed a motet he wrote in 1987 into the original theme for this trio. Each variation is inspired by the different composers that significantly influenced Cuéllar’s musical interests. For the last variations, Cuéllar uses folk material from currulao caucano, a dance from the Pacific region of Colombia. These dances (porro and currulao) are characterized by a strong rhythmic presence, which is an essential element in the folk music of these coastal regions where a significant number of afro descendants are located. In these works, Cuéllar exposes folk Colombian music combined with modal, tonal, and atonal harmonies and develops finely-crafted motivic material to create unique sonorities.

Donald Henriques

Exploring musical works from living composers is fundamental for a contemporary musician. As a violinist and scholar, I have been interested in searching for works for strings that include elements from Latin American music. From the contemporary and traditional Colombian music scene, Juan Antonio Cuéllar stands out as a prominent composer whose inspiration comes from multiple sources, including the Western Canon,1Definition of Western Canon. Weber, William. “Origins of Musical Canon in Eighteen-Century England.” Journal of the American Musicological Society 47, no. 3 (Autumn, 1994): 489, accessed: 25-06-2018.http://www.jstor.org/stable/3128800. twentieth century composers, and popular/folk music. Since his formative years, he has been an admirer of jazz legends such as Oscar Peterson.2“Conversatorio con Juan Antonio Cuéllar y Lincoln Trio (English version),” video, 1:24:07, August 14, 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hth5g_L7x9Q . Cuéllar has great enthusiasm towards twentieth century composers such as Varese, Messiaen, Stravinsky, Bartok, Ligeti, and others. During his early musical career, Cuéllar called himself a “Bartomaniac,” and has a vivid memory of how Ligeti’s piano music left a huge impression on him. Additionally, Cuéllar was greatly influenced by Latin American composers such as Alberto Ginastera (Argentinian) and Blas Emilio Atehourtúa (Colombian).3Conversatorio con Juan Antonio Cuéllar y Lincoln Trio (English version). These influences can be seen in his versatile compositional style.

A native Colombian, Cuéllar studied with composers Eugene O’Brien, Don Freund, and David Dzubay at Indiana University. He has been awarded multiple recognitions such as the Dean’s Prize in Composition at IU, Fulbright Excellence Award, National Composition Award, and others. Cuéllar’s deep commitment of social work led him to become the president of the Batuta Foundation, an institution that oversees music education across the country, and is inspired by El Sistema program from Venezuela.4“Composition alumnus Juan Antonio Cuellar, president of Batuta foundation in Colombia, visits the Jacobs School April 11-13,” Indiana University, (blog), January 3, 2018, https://blogs.music.indiana.edu/composition/2013/04/09/composition-alumnus-juan-antonio-cuellar- president-of-batuta-foundation-in-columbia-visits-the-jacobs-school-april-11-13/. For this article, I will analyze two pieces of Juan Antonio Cuéllar, Pieza para Violín Solo and Conversations for piano, violin, and cello. Both of these works combine modern language with folk Colombian music, where the listener can have a glimpse of Colombian’s musical traditions.

PIEZA PARA VIOLÍN SOLO

Pieza para Violín Solo is a short piece that uses central thematic material focused on a Colombian folk dance, Porro. It was commissioned for Olga Chamorro’s First Violin Competition located in Bogotá, Colombia in 2006. Being a pianist himself he has many solo works for piano, but this work stands out as the only solo instrumental piece among his compositions. Pieza para Violín Solo starts with an introduction Lento Ad Libitum, with Eb as the central pitch. The intervallic construction around Eb consists in 2 elements; descending half-steps (D-C#) and ascending augmented second plus half-step above Eb (F#-G). These intervallic relations combined with the dotted rhythm creates a rhapsodic character that will contrast with the following sections.

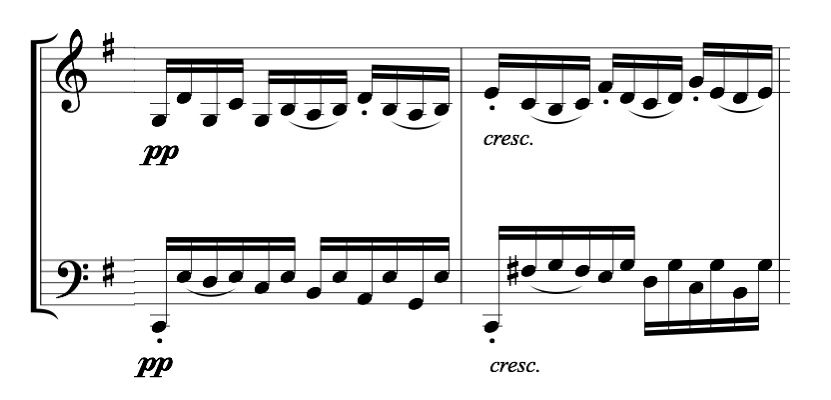

Even though the piece does not have bar lines, the introduction is intended to be played freely (notated Ad Libitum) with clear motivic structure in this section. There are four gestures divided by fermatas. The first gesture (D-C#-Eb) presents the head of the leading motive. The dynamic fortissimo in addition with the short thirty-second notes suggests Cuéllar’s intention to capture the listener’s attention immediately. Similar to the opening, the second gesture features Eb as the central pitch and presents the augmented second interval (Eb-F#) for the first time. Following the second fermata, the third gesture comes as whisper in pianissimo imitating the initial gesture an octave lower. From there, the fourth and last statement is broadly developed to a climatic arrival before reaching the subsequent section. Notice the introduction of A-D arpeggios (open strings) in the last statement. These pitches will be developed further in the piece (see Example 1).

Example 1: Introduction

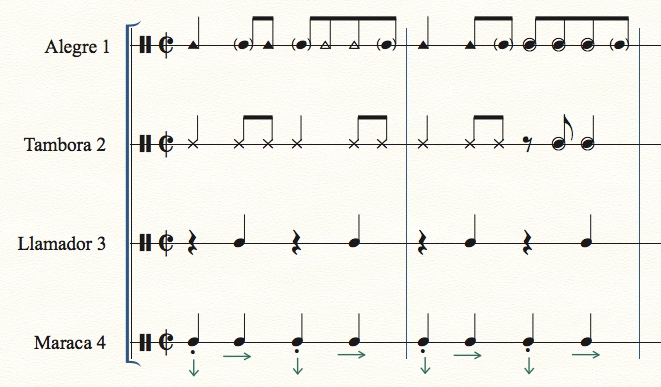

Following the introduction, Tiempo de Porro is based on the folk music and dance of Porro, originated in the Caribbean regions of Sucre and Córdoba in Colombia.5William Fortich, Con bombos y platillos: Origen del Porro, aproximación al fandango y las bandas pelayeras, (Montería: Domus Libri, 1994), 1. The origins of Porro come from the Indo-African cultural heritage in the Caribbean region.6Fortich, 12. Nevertheless, the most characteristic instrument of Porro, which is the melodic gaita, is a Native American wind instrument made of sugar cane, that resembles a clarinet.7Ibid, 2. In Colombia, there is a strong tradition of gaiteros (gaita players) who developed Porro and other folk dances in the region such as cumbia and fandango, sharing the basic rhythmic structure. The basic instrumentation of these dances consists of two gaitas (female and male), maracas, llamador, tambor alegre, and tambora. The gaita hembra (female gaita) doubles the voice and has a strict melodic role. In contrast, the gaita macho’s (male gaita) role consists in a harmonic support showed in a rhythmic pattern, defining the pace of the dance.8Leonor Convers and Juan Sebastian Ochoa. Gaiteros y tamboleros 1: Material para abordar el estudio de la música de gaitas de San Jacito, Bolivar (Colombia). (Bogotá: Pontificia Universidad Javeriana Editorial, 2007), 42-43. Traditionally, the same person plays the gaita macho and maracas at the same time. The maracas establish the tempo and beat of the dance. The llamador, tambor alegre and tambora are different drums of African origin. The llamador (caller) plays the off beats and anticipate the entrances and improvisations of other instruments.9Convers. The tambor alegre (happy drum) determines through the rhythmic pattern what type of dance will be played. It is called “happy” because it improvises along the gaita hembra and voice. Last, the tambora, the largest drum, determines the meter and expands the register with its lower sound.10Ibid. The Porro is in cut time, with a strong emphasis on the off-beats (played by the llamador). Melodically, the Aeolian, Dorian, and Mixolydian modes tend to dominate. Nonetheless, it is common for the voice to sing the leading tone, shifting to minor and major sonorities (see Example 2).11Ibid, 89. See in example 2: the basic rhythmic pattern of Porro

Even though Pieza para Violín Solo does not have measures, the form consists in three parts with an introduction and coda. The following chart shows the structure, divided by motivic material development (see Table 1).

Table 1

The rhythmic structure from Tiempo de Porro changes from the free style of the introduction to a steady beat. For the first time, Cuéllar suggests bar lines without specifying time signature. Notice the up-beat A3 ostinato from the beginning of the section. This motive inspired in the rhythmic structure of Porro will be one of the main elements developed in the piece. Using the open A as pedal, Cuéllar uses left hand pizzicato for the ostinato (see + sign in Example 1) that is shortly replaced with the bow. The string crossings from D to G (in order to play A3) facilitates an accent on this note, setting a pattern as the llamador up beats. The up-beat pattern transforms into an unstable gesture, when changing its placement in the beat. Additionally, the four sixteenth-note grouping shifts to a three sixteenth-note grouping (section A1), thriving to a faster perception of the beat leading into a climatic arrival in C#6 that dissolves rapidly into the B section.

Notice the surfacing melody that highlights a major second and minor third above G4 (see Example 3). This original melody will be developed extensively further in the piece as thematic material. Moreover, Cuéllar uses minor and augmented seconds (material taken from the introduction), establishing these intervals as primary elements for development in this section. Example 4 shows the frequency of these intervals used in sequential motives.

Example 3: Upper melody. Second line of letter A

Example 4: Development of minor seconds and augmented seconds in section A1

In the B section, starting from Tempo I, Cuéllar returns to the opening material of Tiempo de Porro but shifting the ostinato and melody in terms of register. The melody is in the G string, and the ostinato is played in the upper register. Comparing Examples 3 and 5, one can see the same melody (G-Bb-G-A-G-Bb-G-A) and octave lower in Example 4 while the ostinato was transposed and octave higher from A3 to open strings.

Example 5: Opening of section B, shift register.

Starting from the altered motive at the beginning of section B, this section encloses the major motivic and melodic development in the piece. Adding grace notes as ornamentation of the melody in section B, Cuéllar leads to straight sixteenth-notes in B1. In this section, Cuéllar uses double-stops to create a fuller texture in the violin. Notice the use of open strings to facilitate the execution of the passage. Throughout B1, there is an increase in the use of dissonant chords as seconds, sevenths and tritones. Notice how Cuéllar employs major seconds at the beginning of the section and before the climax in B2, he uses only dissonant intervals.

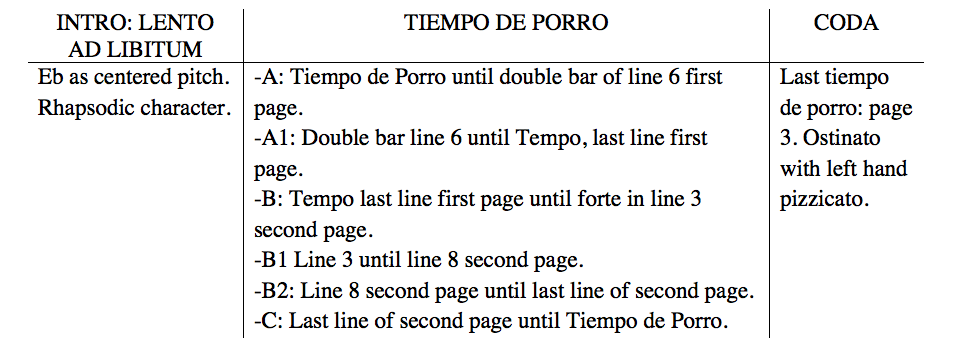

Section B2 encompasses the first major climax of the piece. Marked as fortissimo, the primary melody is played in octaves. The ostinato has escalated to triple-stops leading to dissonant tremolos that dissolve in a descending run into section C (see Example 6)

Example 6: End of section B1. Increment of dissonance to build climax. B2 climax

Section C starts with a rapid build to the second major climax before the coda. In this passage, Cuéllar uses motivic material from A1 and increases the tension by ascending in register and developing more speed to lo más rapido posible (as fast as possible) reaching a high F7 as the culminating arrival in the piece. It is important to highlight the resemblance of some arrival points with the material in the introduction. The peak of these passages are the high notes marked with fermatas dissolving in fast arpeggios or scales into the next section.

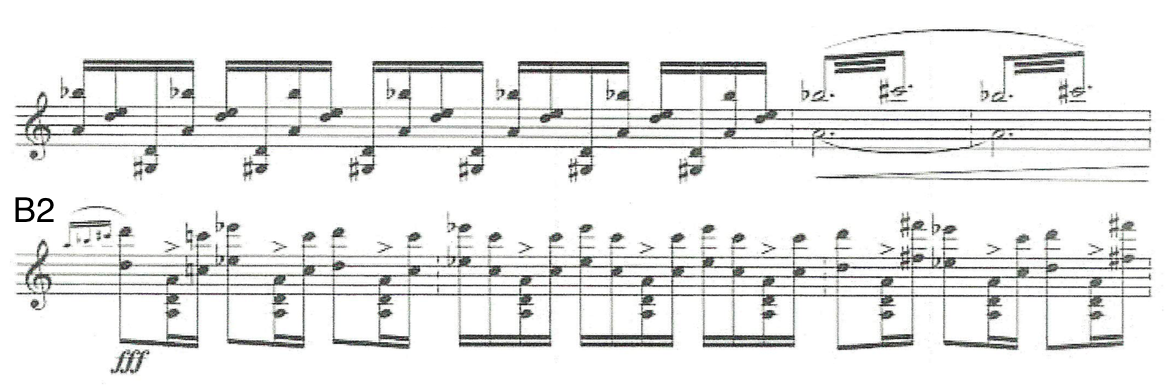

As the beginning of section A, Cuéllar employs left hand pizzicato as an up-beat ostinato throughout the coda. Differently from the opening line in section A, the coda’s ostinato uses open strings A and E, which gives more resonance than the A3 in G string. An emerging melody surfaces in the section marked pianississimo, creating captivating rhythmic contrasts with the left hand pizzicato. See how the rhythmic construction of the melody emphasizes the beats opposing with the up-beat ostinato. This passage requires great coordination due to fact the bowed melody should be played without stopping the pizzicato.

Contrasting with the vigorous opening of the piece and the resolute character of Tiempo de Porro, the character of the coda suggests an introspective mood because of the dynamic drop to pianissimo in combination with the use of a mute. The use of glissandos falling to C4 unveils a relax feeling that identifies the character of folk music. The energetic Porro dance seems now distant, like a whisper disappearing in the horizon (see Example 7).

Example 7: Bowed ending melody with left hand pizzicato

CONVERSATIONS

The Trio “Conversations” Op. 32 was commissioned by the Central Bank of Colombia in 2014. It premiered in August 12, 2015 by the Lincoln Trio at the Library Luis Angel Arango in Bogotá, Colombia. Cuéllar’s compositions shift between tonal, atonal, and modal harmonies. This trio represents the first work where he combines these three worlds, making this piece more accessible for a broader audience.12“Conversatorio con Juan Antonio Cuéllar y Lincoln Trio (English version),” video, 1:24:07, August 14, 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hth5g_L7x9Q .

“Conversations” is a theme and variations where Cuéllar passes through diverse styles, exposing his strongest musical influences. It has a ternary form Fast-Slow-Fast, structured in three attaca movements. The first part includes the theme and variations 1 to 3. The second movement includes variations 4 to 8, and the last part is comprised of variations 9 to 11.

Theme Sacris Solemniis. An Original Four-Voice Motet in Appreciation of Gabriel Fauré.

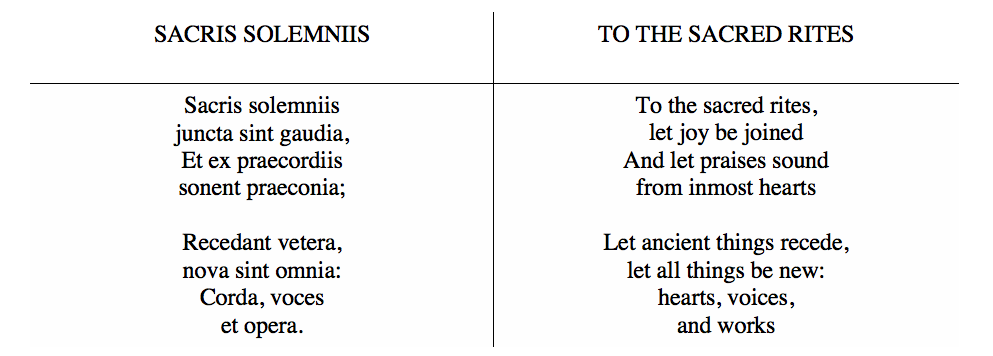

Cuéllar has a deep interest in choral music. During his early twenties, he wrote and conducted numerous choral pieces. The theme of “Conversations” is based on a motet that Cuéllar wrote in 1987. The motet’s text comes from the first verse of St. Thomas Aquinas’s Hymn “Sacris Solemniis.” As stated in his program notes, “Its words [Sacris Solemniis] illuminate the character of the entire cycle. In the piece, the concept of renovation is shaped ‘in conversations’ with the hearts, voices and works of great musical minds: Fauré, Bartók, Jarrett, Stravinsky, Ligeti, Webern, Clara Schumann, J.S. Bach, Paganini, and Ginastera.”13“Program Notes”, Issuu, accessed January 17, 2018. https://issuu.com/banrepcultural/docs/programa_de_mano_lincoln_trio_16-07.

Table 2. Sacris Solemniis text, Latin/English

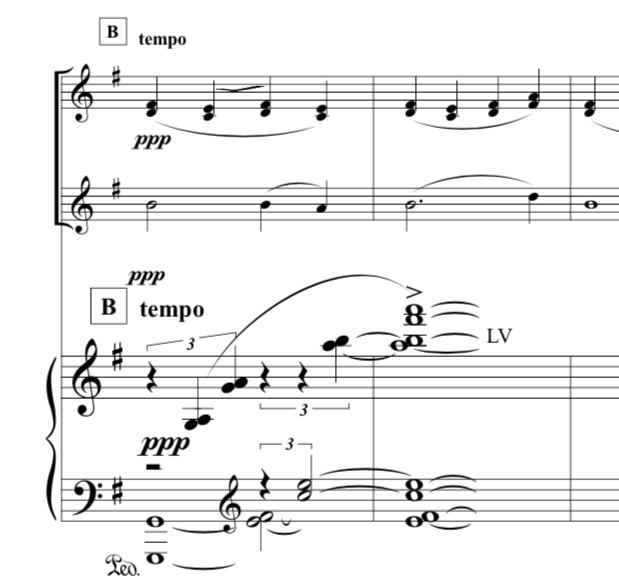

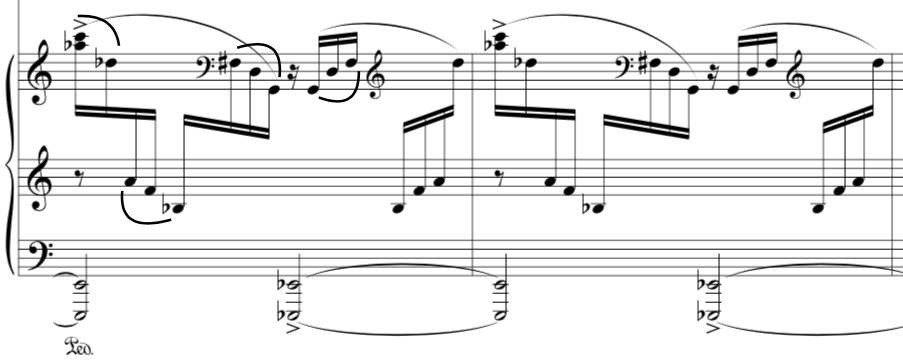

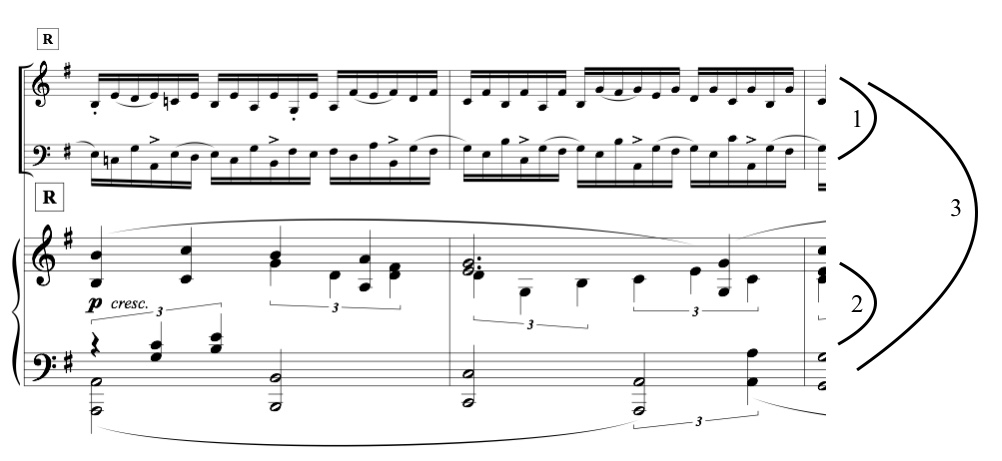

The cello introduces the pastoral soprano voice of the choral in treble clef, cutting through the violin accompaniment in moving thirds. To establish a serene atmosphere, resembling the religious text from the hymn, the violin and cello play with sordine, creating a smooth and tame color that imitates the original choral that the theme is based on. The piano intervenes with quarter-note triplets and secundal intervals that clashes with the tranquil parts of the violin and cello at the end of each short phrase (Example 8). The piano’s conflicting harmonic and rhythmic intervention are a preamble of Cuellar’s development in the variations (Example 9). In m. 9, the piano develops further the 2:3 compound rhythm adding more motion and creating a fuller texture.

Example 8: Piano intervention m.15

Example 9: 2:3 conflicting rhythm in letter A

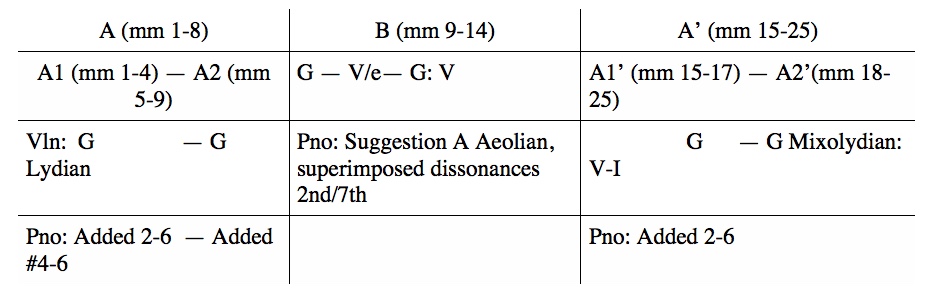

The theme features a tonal-modal ambiguity that will be one of the major harmonic characteristics in the trio. This combination of modal and tonal harmonies is found in many works of Gabriel Fauré, who inspired Cuéllar. The harmonic center of the theme is G. If one takes the melody of theme, it can be easily harmonized around G major with a clear half-cadence in m. 14 and an authentic cadence in m. 24. However, the accompaniment suggests a different harmony. In Example 10, the theme is presented as it is in the original choral by the soprano voice.

Example 10: Original theme in the choral.

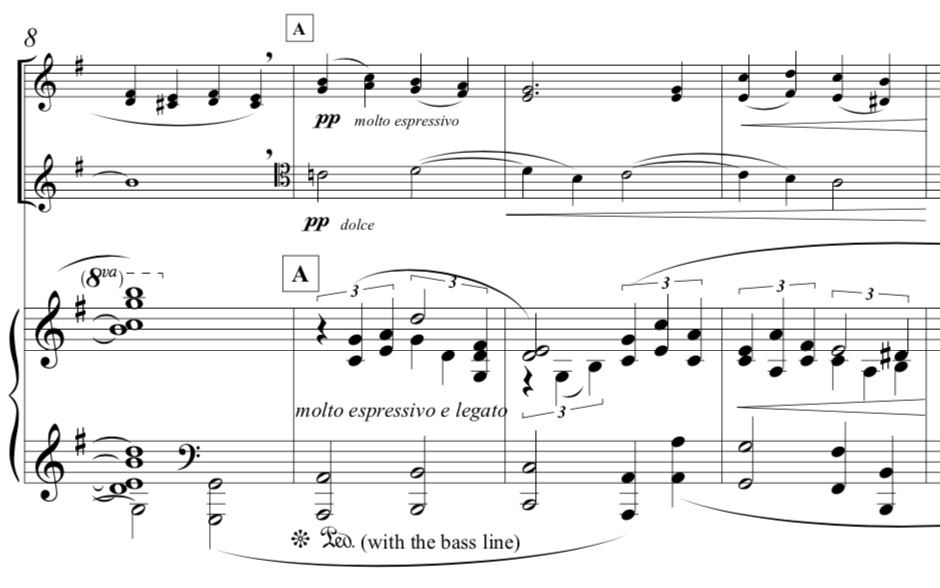

The cello presents the first 4 measures of the theme. The accompaniment in the violin is double-stops in thirds, D-F# and C-E, which diffuses the tonal center, introducing an ambiguous harmony. In m. 4, the piano plays a G2 pedal as a central pitch reference. The secundal intervals in the piano adds the 2nd and 6th degree in G, which creates more ambiguity in the harmony. In m. 5, the violin changes the pitch from C to C# suggesting the G Lydian mode. From mm. 9 to 14, the violin presents the theme in the upper voice of its double-stops. Cuéllar adds more tension by superimposing different harmonies. While the theme suggests G major, the piano seems to imply a different tonal center briefly around A Dorian. (mm. 9 and 10). This ambiguity plus the 2:3 rhythm creates several vertical 2nd and 7th intervallic relations resulting in a more dissonant and unstable passage (see piano voicing in example 9). It is important to highlight how Cuéllar, from the beginning of the theme, exalts these two intervals from the same interval class (ic1, ic2). These interval classes will be one of the main sources for development throughout the piece. After a brief tonicization (V/e), a clear half cadence in G major arrives in m. 14 as a reminder of the central pitch. In m 15, the beginning (A’) comes back with a different harmonic shift in m. 18 to G Mixolydian before leading to a Perfect Authentic Cadence in G major (mm. 23 to 24). In m. 18, the violin takes the lead with the upper voice of the double-stops in sixths, closing the theme. The theme’s structure is a ternary ABA’ form. Each section of the theme is well defined with strong cadences (HC and PAC mentioned before). The following chart shows the structure and superimposing harmonies of each section.

Variation 1: Conversation with Keith Jarrett about Béla Bartók

As in the theme, the cello introduces the melodic subject in the first variation. The presentation of the melody in the tenor clef shows Cuéllar’s treatment of the trio balance. This register helps the cello to be heard easier. Additionally, the light accompaniment in the violin and piano supports the cello part without covering it. Cuéllar keeps the same intervallic relation as the beginning of the theme when the cello plays B-A-B (neighboring tone). Notice the same major second relation (F#-E-F#) in the first measure of this variation (m. 26). These neighboring tones are presented in each instrument as motivic material in the violin playing C#-B-C# (m. 34) and in the piano playing B-A-B (m. 60).

Additionally, Cuéllar superimposes different central pitches and harmonies. One can relate this type of harmonic treatment to Bartok’s use of bimodality and bitonality in numerous works. As stated by István Németh, “The bitonal or bimodal phenomena occupy a central, but by no means exclusive, position in Bartók's piano works.”14István Németh, “Bitonale Und Bimodale Phänomene in Den Klavierwerken Bartóks (1908-1926),” Studia Musicologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 46, no. 3/4 (2005): 257. In this variation, the melody is built in the Locrian mode. The cello’s subject presentation in mm. 26 and 54 is in F# Locrian. Once the violin introduces the melody in m. 34, Cuéllar transposes it by a perfect fifth, C# Locrian. The piano plays the final presentation of the subject in m. 60 in B Locrian, using the same pitches B-A-B as the beginning of the theme in mm. 1 and 2. Nonetheless, the accompaniment in seconds is constantly suggesting another central pitch. For instance, even though the violin melody is clearly emphasizing C# as the central pitch, the piano is playing an E-F# ostinato suggesting a different harmony around F#. This ambivalence occurs throughout each presentation of the subject-melody (see Example 11).

Example 11: Violin melody emphasizing C#. Piano ostinato E-F#

The use of secundal chords is one of the major characteristics in the accompaniment, introduced in the beginning by the violin and piano. These dissonant harmonies are reminiscent of Bartok’s frequent use of clusters in works such as the “Night Music” from the Out of Doors Suite and his first Piano Concerto. Furthermore, one can find secundal intervals in a number of works by Keith Jarrett such as the introduction of Innocence, which highlights Cuéllar's jazz influence. In this first variation, Cuéllar often takes advantage of the open strings for the secundal double-stops such in m. 26 in the violin and m. 42 in the cello, for a more comfortable left hand. In the pickup to m. 60, the piano plays the fourth presentation of the melody, while the violin and cello take the accompaniment role, emphasizing the rhythmic pattern changes. The use of secundal chords becomes stronger at the end of the variation, creating a more dissonant sonority (cluster) that leads to the transition to the next variation based on Stravinsky’s style.

The upbeat melody in jazz style is shaped by asymmetrical rhythmic groups that are changing every one or two measures. The rhythmic component is defined by 7/8, 6/8, and 5/8 meter changes. Cuéllar emphasizes the rhythmic patterns with accents in the accompaniment as well as in the melody giving a strong rhythmic sense. See in Example 11 how the melodic rhythmic pattern in the violin is emphasized by the piano in m. 35 with accented groupings of 2+2+3 for 7/8 and m. 36 with 3+2 for 5/8. In m. 37 the cello reinforces the 7/8 grouping 3+2+2 along with the piano playing strong accents.

In relation to the 2:3 rhythm in the theme discussed above, the asymmetrical rhythmic time signatures in variation 1 can be interpreted as a horizontal version of 2:3. Instead of having triplets against duples vertically as in the choral theme, in this first variation, Cuéllar uses asymmetrical meters such as 5/8 and 7/8, where the groups of 2 and 3 eighth-notes interchange constantly. Characteristics of this type will be found later in the next variations, in more complex textures.

Going to the next variation, Cuéllar uses the ascending sixteenth-notes pick up of the subject-melody as transitional material. In mm. 70 to 73, the violin and cello loop the sixteenth-note motive accompanied by dissonant secundal chords in the piano leading to a cluster chord in variation 2.

Variation 2: A discussion with Igor Stravinsky

Coming from the forward motion of the transitional material of variation 1, the first measures of this variation exposes a tone cluster that includes 10 pitches of the chromatic scale in mm. 74 to 76. This clashing sonority can be interpreted as the arrival point from the secundal chords in variation 1. The cello presents the subject of this variation in m. 77, developing it along with the violin in m. 84. This subject highlights sequences of major and minor seventh intervals (Example 12). Notice in example 12 the melodic construction of ascending sevenths in the violin.

Example 12: Sevenths sequence

The material of the piano part from mm. 77 to 88 (A section) and its correspondence in mm. 99 to 104 (A’ section) is strictly constructed in major sevenths. In Example 13, the arpeggio in m. 77 is all major seventh chords where one can find an ascending seventh major interval from each pitch. Additionally, the chord in the next measure presents the same pattern, this time vertically.

Example 13: Piano part, construction of major sevenths in horizontal and vertical layout.

As one can see, both materials explained above have an upward motion. These ascending lines create a feeling of increased tension that will be interrupted in m. 99 when the B section starts. Using the same rhythmic motive of straight sixteenth-notes in the violin and cello at the introduction of this variation, one can notice the relation of major sevenths between the string instruments. Similar material will return at the end of the variation in m. 110 where the high pitches in the strings build even more tension that will lead to a fortissimo tremolo before variation 3. A strong connection can be found between variations 1 and 2 in the use of the same interval classes (ic1 and ic2). For variation 1, Cuéllar uses the secundal chords as a central sonority in contrast with variation 2, which is based on sevenths.

Variation 3: Etude “In ascendit” a conversation with György Ligeti

As the term “In ascendit” implies, the melodic material of this variation only has ascending motion. One can relate this upward motion to variation 2, which also has motivic material in ascending lines. The ascending lines of variation 3 follow the same intervallic pattern that comes from the third mode of Messiaen’s tones of limited transposition. This mode has four transpositions and it is constructed in the following way:

Whole tone - Half tone - Half tone - Whole tone - Half tone - Half tone, etc.

In the beginning of the second movement “Lento e deserto” of Ligeti’s Piano Concerto, one can find the third mode of Messiaen’s tones of limited transposition. For the first 30 bars, Ligeti uses this collection in every imitative entry using the same transposition. Later, the collection is employed in both hands, transposed a semitone lower.15Richard Steinitz. Gyorgy Ligeti: Music of the Imagination. (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 2003), 326. Also, Ligeti used other modes of Messiaen’s scales in several of his works. In Example 14, the beginning of variation 3 presents this scale pattern (whole-half-half) in the violin and cello in eighth-notes, and in the piano in sixteenth-notes.

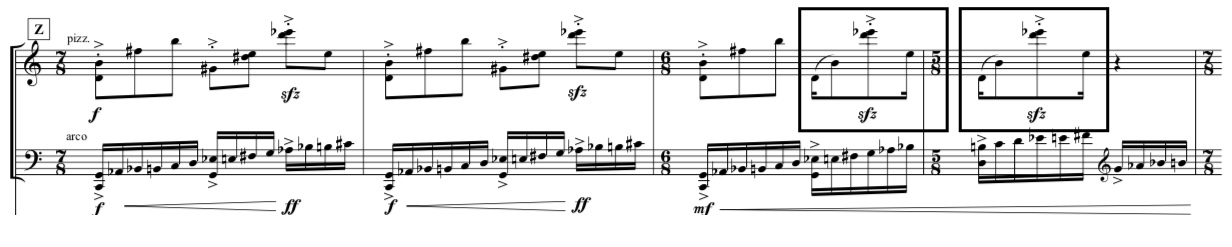

As in variation 1, Cuéllar also uses time signature changes of 7/8, 6/8, and 5/8 in every measure suggesting the 2:3 horizontal rhythmic conflict discussed in variation 1. Another similarity between these variations is in the emphasis given to the rhythmic grouping 3+2+2 for 7/8, 3+3 for 6/8, and 3+2 for 5/8. This emphasis is shown by accents, sforzandi, and double stops as circled in Example 14. These polymetric grids are a common feature found in many of Ligeti’s work, such as the first movement of the Piano Concerto, where meters such as 12/8 and 4/4 are grouped asymmetrically.16Steinitz, 323. Additionally, one can find polymetric examples in his Piano Etude No. 1 Désordre.

Example 14: Third mode of Messiaen’s tones of limited transposition

From mm. 245 to 248, the violin changes the rhythmic dynamic, emphasizing the weak beats with accented pizzicato. This contrasting rhythm opposes the rest of the variation, presenting variety and unexpected shifts. Additionally, interval classes 1 and 2 are a basic element of construction of this variation, as the past variations. One can find these interval classes horizontally in the scale itself as well as vertically in all three instruments as chords and double stops.

Variation 4: A Quite Tonal Conversation with Anton Webern

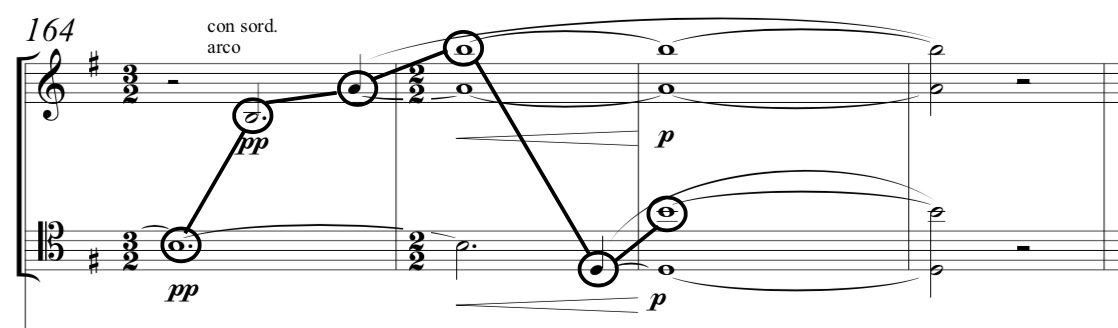

The second movement of the trio represents the slow middle section that is comprised of variations 4 to 8. After the first three agitated variations, the Lento in variation 4 encloses a drastic character change into a mystical atmosphere in the style of Anton Webern. For this variation, Cuéllar presents the same pitches of the theme in pointillistic technique, where each pitch of the theme passes through different octaves among all three instruments. As in the theme, Cuéllar uses the same modal ambiguity, with G as the central pitch. In this variation, Cuéllar keeps the same structure of the theme and same number of measures. Nonetheless, given the spaced out writing, thin texture, and tempo, this variation has a feeling of rhythmic expansion. Example 15a-b compares the subject presented by the cello in the theme and the beginning of variation 4. The exact same pitches B-B-A-B-D-B are distributed in a 3-octave range between the violin and cello.

Example 15a, 15b: Beginning of original theme (15a) and pointillistic technique (15b)

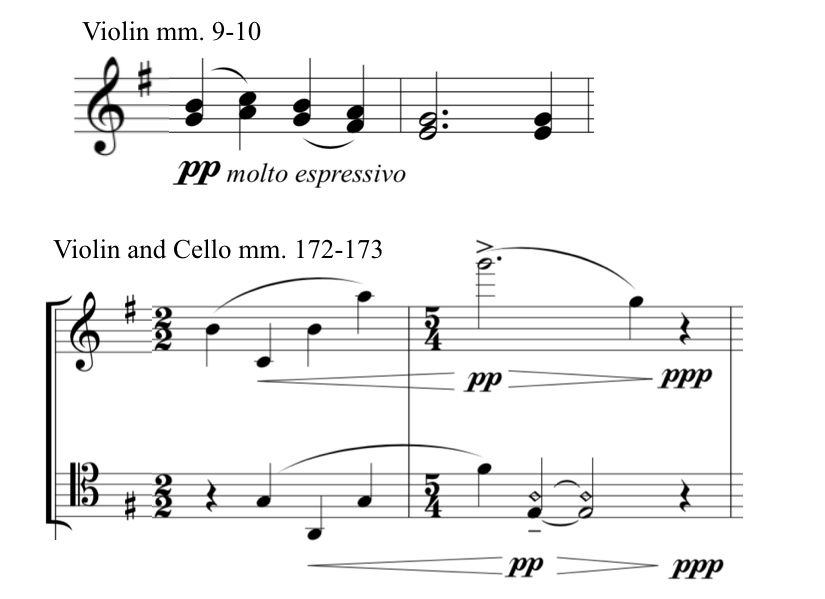

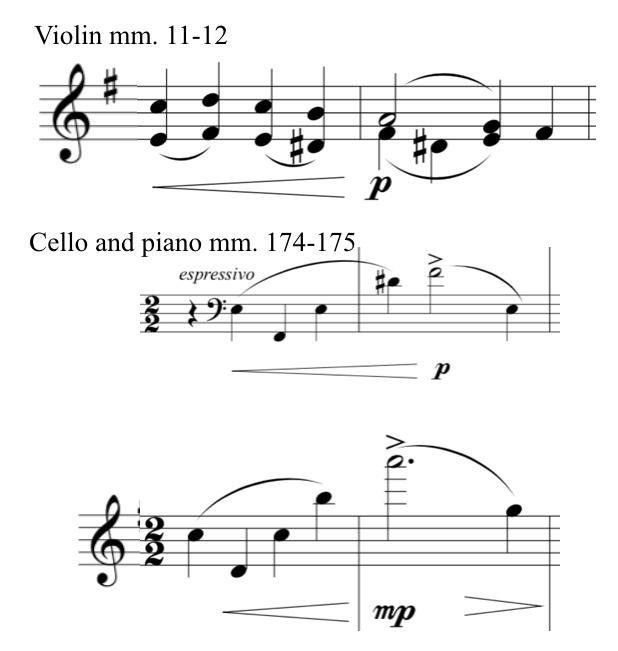

Different from the theme, the piano material splits between the quarter-note triplets as in mm. 4 to 5 and, mm. 7 to 8, and the thematic and secondary material of the subject in Webern's style. In the B section (mm. 172 to 173), the double-stops played by the violin in the theme (mm. 9-10) are distributed to the violin and cello, one beat apart. Cuéllar gives the same treatment to mm. 174 to 175 between cello and piano.

Examples 16a, 16b: Presentations of theme in pointillistic style with displaces harmonies

Even though Cuéllar is using the same pitches (thus same harmony), the resulting sonority is considerably different from the original theme. The distribution of each line, being played one beat apart, creates vertical dissonances. See in Example 16 the resulting intervals between the violin and cello parts in mm. 172 to 173 (p4, +2, +2, -2). Additionally, Cuéllar employs interval classes 1 and 2, as in the former variations, as a unifying element. One can find these interval classes vertically and horizontally in every measure. Variation 4 represents a turn back to tonality/modality from the non-tonal treatment of variations 2 and 3. However, the voice treatment focusing on ic 1 and 2 diverts the theme sonority into unstable and defusing harmonies.

Variations 5 and 6: Intimate confessions to Clara Schumann

One of the most prominent elements of variations 5 and 6 is the rhythmic complexity between the parts such as syncopations, quintuplets, half-note, and quarter-note triplets combined with duplets. In variation 5, one can see how Cuéllar took the 2:3 rhythmic conflict discussed in earlier variations to a new level. See in Example 17 the quarter-note triplets and eighth-note quintuplets against quarter-notes in the piano part in mm. 196 to 197. In the violin part, the half-note triplets and quarter-notes are constantly clashing with the quarter-note triplets in the piano accompaniment.

Example 17: Rhythmic complexity among all parts

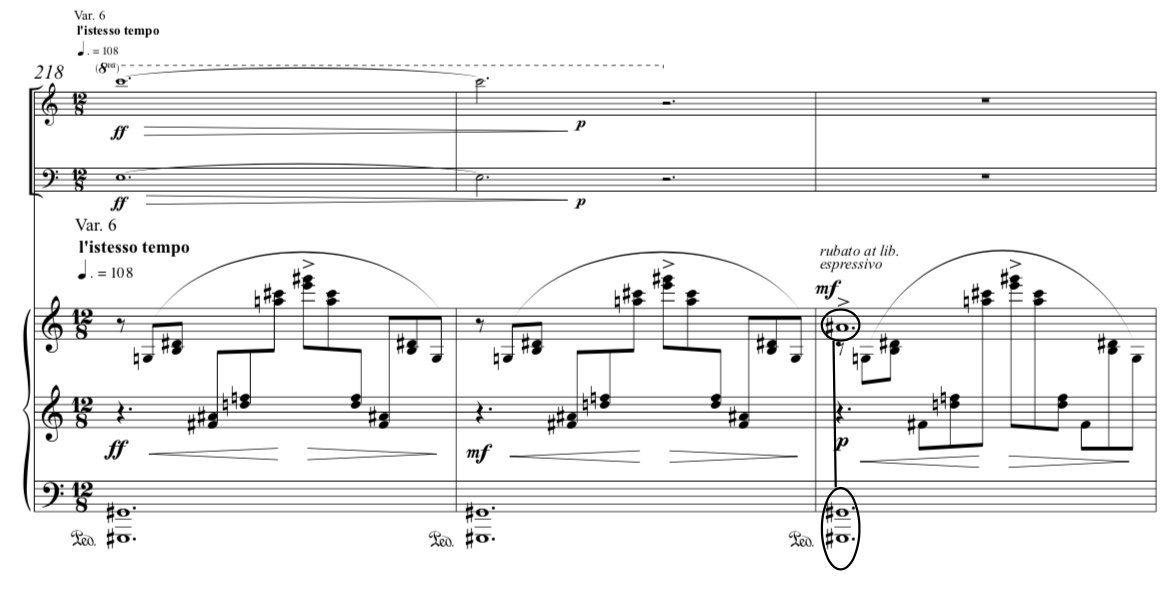

During variation 5, the piano accompanies the dialogue of the violin and cello. As in variations 1 to 3, the cello presents the melodic line with the characteristic neighboring tone motive of the original theme, in this case F-Eb-F in m 190. An embellished presentation comes few measures later (mm. 193 to 194) followed by a developed violin entrance. This motive appears in several occasions among all three parts. The cello plays it one more time in m. 204. During the piano solo in variation 6, the A section of the original theme is played starting in m. 221. The final presentation comes in the violin in m. 234 in a climatic entrance. From m. 192, each entrance of the strings starts with ascending three notes that will accelerate rhythmically throughout variations 5 and 6.

As in the former variations, interval classes 1 and 2 are a predominant constructive tool. For instance, in variation 5, the piano accompaniment plays sevenths every beat regardless of the triplet or duplet rhythm. See in Example 17 the intervallic relations of the ostinato in the piano. Furthermore, all the grace notes in the strings are sevenths. (See the violin line in Example 17, A-G#, E-D# and C-B).

In variation 6, the piano’s solo construction is based on the same interval classes. See in Example 18 the G# pedal in the left hand clashing in m. 220 with the whole-note A#. Additionally, the ascending and descending arpeggios written in major thirds from m. 218 to 229 results in major sevenths. It is important to highlight this treatment in the piano arpeggios discussed earlier in variation 2. This pianistic writing of ascending and descending thirds are also found in a number of Clara Schumann’s compositions such as the first movement of her Piano Concerto and the introduction from Variations de Concert.

Example 18: Construction of seconds and sevenths

As mentioned above, in m. 221, the piano presents the A section of the theme in A# as the central pitch instead of the original G center. However, the pedal in the bass will continue in G# creating a major second dissonance throughout m. 226. In m. 234, during the climatic entrance of the violin, the piano arpeggiated chords change to single-note arpeggios still highlighting the 7th interval. See in Example 19 how the external notes of the three sixteenth-notes grouping are major 7ths.

Example 19: piano part m. 236: Outline of major sevenths

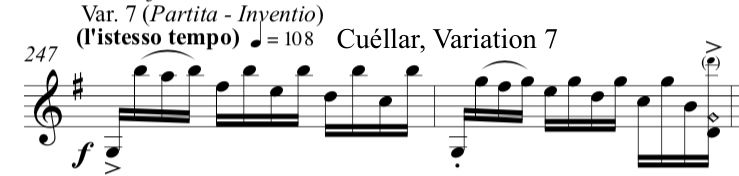

Variations 7 and 8: A Baroque Digression: Partita, Inventio, Chorale Prelude, Transition

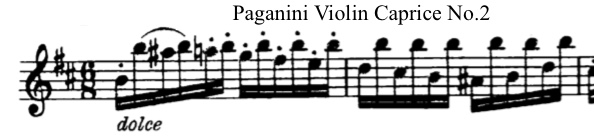

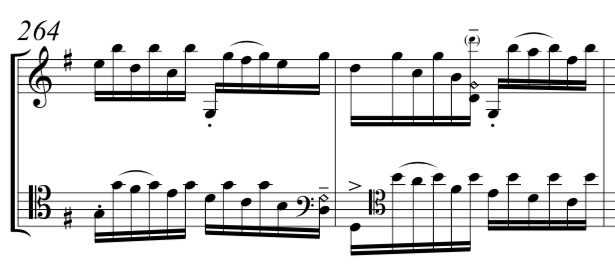

The baroque digression starts with a violin solo interrupting the piano discourse at the end of variation 6. The solo is inspired by Paganini’s Caprice for Solo Violin no. 2. Notice in Example 20 the similarities of both passages, such as the high note pedal while moving in a descending line. This writing creates large leaps of considerable technical challenge due to the string crossings. For some of the largest leaps, Cuéllar uses harmonics to avoid big shifts. In m. 263 the cello joins the violin line in a 1:1 counterpoint with the same melodic treatment as J.S. Bach’s invention BWV 772-786. See in Example 21 how the articulation (slurs) switches between the strings. From m. 272 to variation 8, the violin changes its grouping from sixteenth-notes sextuplets to groups of 4 sixteenth-notes creating a 2:3 rhythmic feeling (see Example 21).

Example 20a, 20b: Comparison between Paganini Caprice (20a) and Violin Solo digression (20b)

Example 21a, 21b: Articulation changes (21a) and 2:3 sixteenth-note grouping between string parts (21b)

In variation 8, (theme and transition) the piano plays the original theme while the strings continue the 1:1 counterpoint. This is one of the most rhythmically complex passages in the trio. In Example 22, one can see three rhythmic layers. First, the articulation interchanges between the strings as in variation 7, which results in different accentuation between the parts because of the slurs and string crossings happening at different times. Second, for the B section of the theme, the piano part is playing 2:3 quarter notes as the original theme. Last and most importantly, the strings are playing in a different tempo and time signature than the piano. The 9/8 with dotted quarter-note = 72 in the strings conflicts with the 4/4 quarter-note = 96 in the piano. Each quarter-note of the piano equals 4.5 sixteenth-notes of the strings. As stunning as this statement sounds, every measure still lines up among all three instruments. This passage represents a great challenge in terms of ensemble. Despite the complex rhythmic writing, the harmony is kept the same for all three instruments, which makes it the connecting element in this passage.

Example 22: Three rhythmic layers. m. 286

In m. 292, the transition to the next movement starts with a D pedal in all parts. Cuéllar still uses interval classes 1 and 2 as thematic material in the piano. In mm. 292 to 293, the piano has the melody in treble clef C-A, C-A-G, with C starting both motives and clashing with the D pedal. Additionally, in the next measures before the time signature changes, the piano has the melodic line C-G#-G-D#, C#-C-G#-G-D#. Notice the relation of 7ths between some of these intervals.

In the second part of the transition (m. 296), the syncopation takes an essential role. All three parts convolute with accents at different places, creating a complex and changing compound rhythm until the piano solo in m. 308, where it introduces the rhythmic subject of the third movement. Notice the secundal chords in the piano every downbeat except mm. 296 and 298. This piano writing resembles the secundal chords in the ostinato in variation 1 (see Example 23).

Example 23: Transitional compound rhythm of third movement

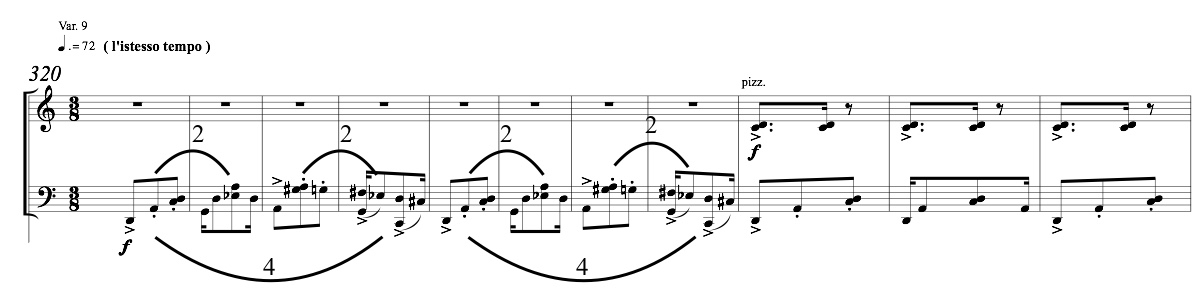

Variations 9 and 10: Conversations with Alberto Ginastera about a Dance from the Colombian Pacific

Variations 9 to 11 comprises the fast third movement. As in past variations, the cello introduces the principal subject of these variations. This subject has a dance rhythmic feeling based on a folk dance from the Colombian Pacific, called Currulao Caucano.17Conversatorio con Juan Antonio Cuéllar y Lincoln Trio (english version),” video, 1:24:07, August 14, 2015, https://wwwl.youtube.com/watch?v=hth5g_L7x9Q The origins of Currulao comes from the afro-descendent communities located in the Colombian Pacific coast. The word Caucano refers to the state of Cauca, one of the coastal regions in the Pacific. In the book Arrullos y Currulaos by Juan Sebastian Ochoa, he characterizes Currulao as a social event, a large party without religious character where people gather to sing, dance, tell jokes, stories, drink, and eat.18Juan Sebastian Ochoa, Leonor Convers, and Oscar Hernández, Arrullos y Currulaos, Volume 1 (Bogotá: Pontificia Universidad Javeriana Editorial, 2015), 56.

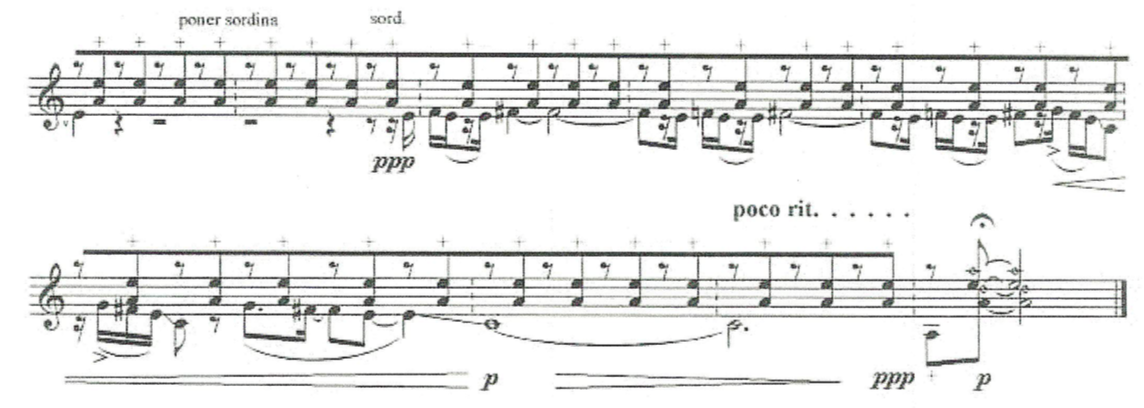

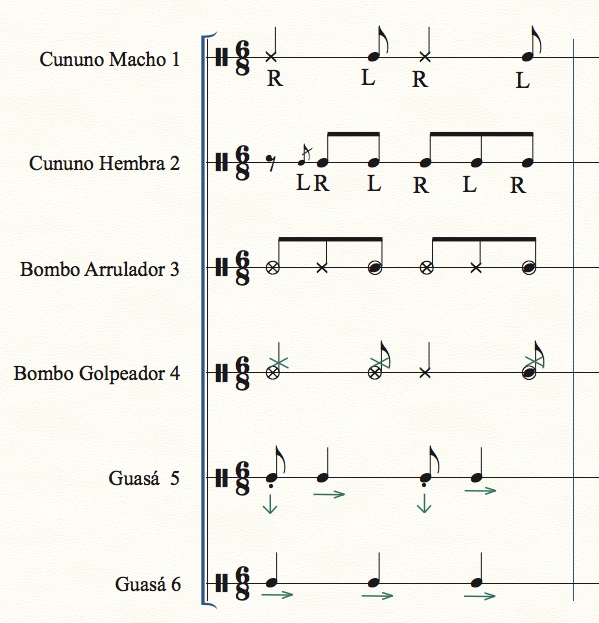

The rhythmic component is one of the most important elements of this dance. Originally in 6/8, Currulao has a meter duality between 3/4 and 6/8. See in the Example 24 the rhythmic base of Currulao and how some instruments, such as guasá (6), have a clear rhythmic pattern in 3/4 in contrast with other instruments in 6/8 as cununo macho and bombo arrullador. In terms of melodic and harmonic construction, Currulao is based on major and minor diatonic-like scale without the 6th degree. As in tonal music, the harmony has a tension-release relationship as dominant-tonic.19Ochoa, 87.

Example 24: 6/8-3/4 duality. Currulao rhythmic base

The melodic treatment of the cello opening in variation 9 suggests a similarity to Currulao. In the first section of this variation, (mm. 320 to 343) D is the central pitch. During this whole section, the 6th scale degree is missing. Notice there is no B or Bb in any of the parts. As in former variations, the secundal chords established an essential sonority. See in Example 25, the cello opening and interval classes 1 and 2 in most of the double stops.

In terms of the rhythmic structure, the cello opening combines accents on the downbeats with syncopated motives, creating a rhythmic and symmetric pattern that will be developed further in the movement. See in Example 25 the symmetric construction phrase of (2+2) (2+2). The violin entrance in m. 328 conflicts with the cello pattern, resulting in a 2:3 rhythmic construction.

Example 25: Cello opening and violin entrance 2:3 rhythm

It is important to highlight Cuéllar’s use of interval classes 5 and 7 in these variations (use of perfect 4ths, 5ths and tritones). In m. 328, the piano introduces a new material of chromatic perfect 5ths in sixteenth-notes. This motive will be developed in all three parts. This material contrasts with the surrounding elements because of its intervallic structure. Either chromatic scales or perfect 5ths motives have been written in the previous variations. Additionally, motivic perfect 4ths are presented in the violin m. 344, imitated by the cello later in m. 349. The use of this new sonority can be related with Ginastera’s first period where he used folk music elements. As stated by Deborah Schwartz-Kates,

He [Ginastera] drew his inspiration from the gauchesco tradition that upheld the gaucho (native horseman) as an idealized national emblem. He created a powerful image of this figure with a chord derived from the open tuning of the gaucho’s guitar strings. The resulting sonority, E–A–d–g–b–e′, evokes a sound image of the instrument…20Deborah Schwartz-Kates. “Ginastera, Alberto,” Oxford Music Online, 1 July 2014, https://doi-org.proxy1.cl.msu.edu/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.11159 .

One can relate the open strings of the gaucho’s guitar strings (mostly descending fifths) to Ginastera’s use of parallel fourths and fifths found in his first period compositions, such as in the ballet Estancia.

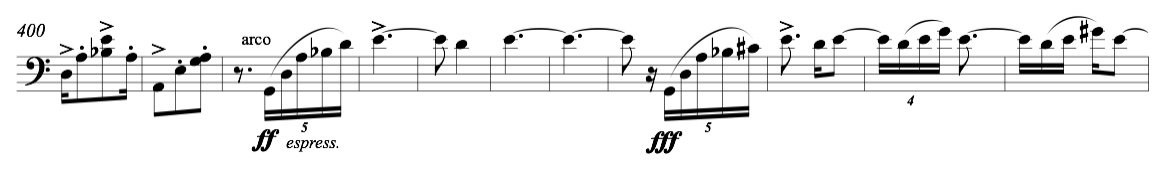

In variation 10, the violin presents the subject supported by the piano two measures later. The cello plays the same subject in pizzicato one measure apart, creating a syncopated counterpoint among the parts with compound rhythm of sixteenth-notes (See Example 25 for the presentation of the subject). In mm. 403 to 411, the cello introduces the thematic neighboring tone motive of the original theme in syncopation. From m. 408, the cello develops this motive further with rhythmic ornaments. This flourished motive development is presented in the violin in m. 417.

Example 26: Original motive ornamentation in the cello part

In m. 434, a transition starts with an interlude character that contrasts from the vigorous and exciting previous spirit to a calmer character in 2/4 and 3/4 (contrasting with the preceding 3/8). The melody is played in octaves by the strings, featuring the pitches of the original motive. Additionally, Cuéllar employs interval classes 1 and 2 as a central structure, especially in the piano. Notice the secundal chords in the cello and piano in the first measures of this passage. Moreover, the sixteenth-notes in the piano F-B-E features a major seventh in the outer intervals. This motive can be related to m. 234 in variation 6.

Variation 11: Coda

Keeping the same energetic character of variations 9 and 10, the coda combines material of previous variations. At the beginning, while the piano keeps playing the three sixteenth-note motive (material from variation 6), the cello plays the ascending scales from Ligeti’s variation 3 (Example 27). From m. 479, Cuéllar combines the material of variation 3 with syncopated rhythmic motives from variations 9 and 10 in the strings.

Example 27: Material from variation 3 (Ligeti) and variation 9-10

In m. 495, Cuéllar presents new material emphasizing the second eighth-note of the measure. Notice the use of interval classes 1 and 2 in all three instruments. After building tension throughout the section by increasing dynamics, and denser texture in the strings (straight sixteenth-notes), the end of the trio is concentrated in the principal subject from variations 9 and 10, played in vigorous unison by all three instruments. Passing through diverse styles throughout the variations, Cuéllar decides to present this rhythmic subject as the arrival point of the whole work. The unison gives a stronger sense in his intention to enunciate this subject. Decidedly, Cuéllar adds a 4/8 bar in m. 525 for an unstable and unpredictable turn at the end of the trio (Example 28).

Example 28: Three-part unison. 4/8 addition

CONCLUSION

In his works Pieza para Violín Solo and Conversations, Cuellar’s musical development can be seen in his resourcefulness of motivic material, creating infinite musical possibilities. In Pieza para Violín Solo, Cuéllar uses few intervallic relations such as a melody based on major seconds and minor thirds, semi-tone and augmented second intervallic development, and few rhythmic motive cells to compose a concise but eloquent piece with great contrasting material and expression. In Conversations, a leitmotif based on the first pitches of the theme (B-A-B) is seen throughout. Additionally, Cuéllar’s use of interval classes 1 and 2 is a unifying element presented regardless of the variations’ styles. Cuéllar’s musical flexibility is exhibited in a number of variations, based on an original motet, of very different styles.

The influences of Colombian folk music in Cuéllar’s works exposes rich Latin American traditions characterized by substantial rhythmic elements from African legacy. The Porro and Currulao dances come from the Caribbean and Pacific regions of Colombia, where a significant number of afro-descendent communities established. These lively dances are great examples of the traditions portrayed in these regions.

Cuéllar’s extensive influences from popular music, the Western Canon, and contemporary music can be heard throughout his compositions. He has become a leading composer in Colombia, where one can find his versatility in works that reach all types of audiences, while leaving behind his personal signature in each one of his compositions. From contemporary to popular music, Cuéllar’s music is heard in concert halls, as well as national broadcasted television, such as his recent commission for the mass of Pope Francis in his visit to Colombia. Cuéllar’s works resonate at many levels, influencing the present music scene inside and outside Colombia.

Notes

1 Definition of Western Canon. Weber, William. “Origins of Musical Canon in Eighteen-Century England.” Journal of the American Musicological Society 47, no. 3 (Autumn, 1994): 489, accessed: 25-06-2018. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3128800.

2 “Conversatorio con Juan Antonio Cuéllar y Lincoln Trio (English version),” video, 1:24:07, August 14, 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hth5g_L7x9Q .

3 Conversatorio con Juan Antonio Cuéllar y Lincoln Trio (English version).

4 “Composition alumnus Juan Antonio Cuellar, president of Batuta foundation in Colombia, visits the Jacobs School April 11-13,” Indiana University, (blog), January 3, 2018, https://blogs.music.indiana.edu/composition/2013/04/09/composition-alumnus-juan-antonio-cuellar- president-of-batuta-foundation-in-columbia-visits-the-jacobs-school-april-11-13/.

5 William Fortich, Con bombos y platillos: Origen del Porro, aproximación al fandango y las bandas pelayeras, (Montería: Domus Libri, 1994), 1.

6 Fortich, 12.

7 Ibid, 2.

8 Leonor Convers and Juan Sebastian Ochoa. Gaiteros y tamboleros 1: Material para abordar el estudio de la música de gaitas de San Jacito, Bolivar (Colombia). (Bogotá: Pontificia Universidad Javeriana Editorial, 2007), 42-43.

9 Convers.

10 Ibid.

11 Ibid, 89.

12 “Conversatorio con Juan Antonio Cuéllar y Lincoln Trio (English version),” video, 1:24:07, August 14, 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hth5g_L7x9Q .

13 “Program Notes”, Issuu, accessed January 17, 2018. https://issuu.com/banrepcultural/docs/programa_de_mano_lincoln_trio_16-07.

14 István Németh, “Bitonale Und Bimodale Phänomene in Den Klavierwerken Bartóks (1908-1926),” Studia Musicologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 46, no. 3/4 (2005): 257.

15 Richard Steinitz. Gyorgy Ligeti: Music of the Imagination. (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 2003), 326.

16 Steinitz, 323.

17 Conversatorio con Juan Antonio Cuéllar y Lincoln Trio (english version),” video, 1:24:07, August 14, 2015, https://wwwl.youtube.com/watch?v=hth5g_L7x9Q

18Juan Sebastian Ochoa, Leonor Convers, and Oscar Hernández, Arrullos y Currulaos, Volume 1 (Bogotá: Pontificia Universidad Javeriana Editorial, 2015), 56.

19 Ochoa, 87.

20 Deborah Schwartz-Kates. “Ginastera, Alberto,” Oxford Music Online, 1 July 2014, https://doi-org.proxy1.cl.msu.edu/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.11159.

Bibliography

“Composition alumnus Juan Antonio Cuellar, president of Batuta foundation in Colombia, visits the Jacobs School April 11-13.” Indiana University. Accessed January 3, 2018. https://blogs.music.indiana.edu/composition/2013/04/09/composition-alumnus-juan-antonio- cuellar-president-of-batuta-foundation-in-columbia-visits-the-jacobs-school-april-11-13/.

“Conversatorio con Juan Antonio Cuéllar y Lincoln Trio (english version).” Video. 1:24:07. August 14, 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hth5g_L7x9Q.

Fortich, William. Con bombos y platillos: Origen del Porro, aproximación al fandango y las bandas pelayeras. Montería: Domus Libri, 1994.

Németh, G. István. “Bitonale Und Bimodale Phänomene in Den Klavierwerken Bartóks (1908-1926).” Studia Musicologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 46, no. 3/4 (2005): 257-94. http://www.jstor.org.proxy1.cl.msu.edu/stable/25164470. doi: 10.1556/smus.46.2005.3-4.2

Ochoa, Juan Sebastian, Leonor Convers, and Oscar Hernández, Arrullos y Currulaos, Volume 1. Bogotá: Pontificia Universidad Javeriana Editorial, 2015.

Convers, Leonor and Juan Sebastian Ochoa. Gaiteros y tamboleros 1: Material para abordar el estudio de la música de gaitas de San Jacito, Bolivar (Colombia). Bogotá: Pontificia Universidad Javeriana Editorial, 2007.

“Program Notes.” Issuu. Accessed January 17, 2018. https://issuu.com/banrepcultural/docs/programa_de_mano_lincoln_trio_16-07.

Schwartz-Kates, Deborah. “Ginastera, Alberto.” Oxford Music Online. 1 July 2014. https://doi-org.proxy1.cl.msu.edu/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.11159 doi: 10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.11159.

Steinitz, Richard. György Ligeti: Music of the Imagination. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 2003.

Weber, William. “Origins of Musical Canon in Eighteen-Century England.” Journal of the American Musicological Society 47, no. 3 (Autumn, 1994): 488-520. Accessed: 25-06-2018. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3128800. doi: 10.1525/jams.1994.47.3.04x0015o.