Abstract

This article explores J. S. Bach’s use of motives as a means to create unity in his large-scale instrumental works. Using the G-Major Suite for Cello, BWV 1007, as a case study, it traces how Bach takes simple elements and expands them to create a multimovement dance suite. To support its arguments, the article considers other solo instrumental compositions by Bach for keyboard and violin. By looking at motive as a way to unify multiple movements, performers of Bach’s music can modify their interpretations in order to illuminate motivic connections.

Vincent Benitez

Introduction

In the history of music, there has been an ongoing question regarding how a composer creates a large-scale, cohesive work. Every composer must grapple with this challenge in his or her own way. One of the clearest schools of thought related to this question derives from the work of Austro-Germanic composers, most notably that of W. A. Mozart and Ludwig van Beethoven, and extending to Felix Mendelssohn, Johannes Brahms, and Arnold Schoenberg. In short, these composers focused on motives and their development in order to provide structural coherence for their large-scale works. For Schoenberg, “The . . . motive is . . . the ‘germ’ of the idea. Since it includes elements . . . of every subsequent musical figure, one could consider it the ‘smallest common multiple.’ . . . Everything depends on its treatment and development.”1Arnold Schoenberg, Fundamentals of Musical Composition (London: Faber and Faber, 1967), 8. In Beethoven’s compositional approach, what he calls das Thema is one of the more appropriate terms for this practice because it engenders a motive’s protean nature.2Jan Swafford, Beethoven: Anguish and Triumph (New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2014), 939. Swafford describes das Thema as “the all-important opening theme that sets the mood, the leading motifs from which other themes will be made, and the general direction of the whole piece.”

It is well established that motivic development is a hallmark of Western Art Music, particularly since the advent of sonata form in the Classical period. In large-scale musical forms, motivic elements unify the movements within an aesthetic whole (e.g., the “Fate motive” of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, Op. 67). However, in the Baroque period, while motivic elements abound in compositions, how a motive unifies larger-scale instrumental works, especially those outside the genres of the concerto or fugue, for example, is not readily discussed. During a recent piano recital I attended, the performer played J. S. Bach’s English Suite No. 3 in G Minor, BWV 808, and decided to replace the Gigue with the one from the G-Major Partita, BWV 829.3The recital was given by pianist Stephen Beus at Riceland Hall in Jonesboro, Arkansas, on February 20, 2017. There currently seems to be more flexibility in programming Bach’s solo instrumental works, which may harken back to the past. With respect to the Sonatas and Partitas for violin, Zay David Sevier notes that during the rediscovery of Bach’s music in the nineteenth century, the Solo Violin Sonatas were not performed in their entirety, nor were they performed without accompaniment; see Zay David Sevier, “Bach’s Solo Violin Sonatas and Partitas: The First Century and a Half, Part 2,” Bach 12, no. 3 (July 1981): 21–29. Even in the early twentieth century, violinists such as Fritz Kreisler (1875–1962) would rarely program an entire Bach Sonata or Partita on a recital program. While this Romantic dark-to-light transformation was convincing, there was something amiss. Upon further study of the Suite and the Partita, there was a salient feature that separated them (besides their modality)—namely, the order of their voice parts. Specifically, in the Prelude to the G-Minor English Suite, Bach uses a descending voice order from soprano to bass in the imitative opening, and he does the same in the Gigue (see Examples 1 and 2, respectively). Conversely, the G-Major Gigue from the Partita opens with the alto voice before moving on to the soprano and then to the bass (see Example 3).4The Prelude of the G-Major Partita shares an interesting feature with its Gigue, in that both movements prominently feature rests as part of the construction of their opening gestures.

Example 1. Prelude, English Suite in G Minor, BWV 808, mm. 1–7

Example 2. Gigue, English Suite in G Minor, BWV 808, mm. 1–8

Example 3. Gigue, Partita in G Major, BWV 829, mm. 1–8.

The imitative openings of the English Suite’s Prelude and Gigue in G Minor share a fiery dive to the lowest note before rising back up, resembling the letter “V,” intensified by the contrary motion between the hands. Yet, the question still arises as to how Bach fosters structural coherence in his large-scale solo instrumental works that transcends the Baroque dance suite. Is there a creative thread that connects a suite’s movements so that one cannot arbitrarily pick a key and create a new dance suite at will from existing movements taken elsewhere from Bach’s oeuvre?

Motives serve as that thread, and their treatment is an important process that Bach uses to unify solo instrumental works. Although motives may have a different function and name depending on the particular musical aesthetic of the time, their treatment is a salient characteristic of Austro-Germanic music. Indeed, for Bach, the inventio of musical rhetoric shapes his works; for Beethoven, it is das Thema; and for Schoenberg, developing variation guides compositional structure. And in my approach, aspects of musical rhetoric are combined with developing variation’s crafting of motivic material. Using the first Cello Suite in G Major, BWV 1007, I will demonstrate in this article how the working out of motivic material creates cohesion, and how highlighting motivic elements can inform interpretation.

Bach’s Inventio

In the title page of his Inventions and Sinfonias (1723), Bach not only elucidates their pedagogical purpose but also connects them to musical rhetoric through the concept of inventio, the first part of a musical oration that deals with the invention of musical ideas (i.e., motivic material).5See Joel Lester, Bach’s Works for Solo Violin: Style, Structure, Performance (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999), 42; David Schulenberg, The Keyboard Music of J. S. Bach (New York: Schirmer Books, 1992), 151; and Vincent P. Benitez, “Musical-Rhetorical Figures in the Orgelbüchlein of J. S. Bach,” Bach 18, no. 1 (January 1987): 3–6. Johann Mattheson (1681–1764) is noted for his writings regarding the connections between rhetoric and music, particularly involving the structure of a musical oration in Der vollkommene Capellmeister (1739). See Johann Mattheson, Der vollkommene Capellmeister (Hamburg: Christian Herold, 1739); trans. Ernest C. Harriss as Johann Mattheson’s Der vollkommene Capellmeister: A Revised Translation with Critical Commentary (Ann Arbor: UMI Research Press, 1981), 469–72. Bach also refers in the title page to elocutio, the last part of a musical speech that focuses on the verbalization or delivery of musical ideas, after they have been subjected to formal ordering (dispositio) and elaboration (decoratio). As Laurence Dreyfus notes, “Bach’s compositional procedures often amount to an obsessive search for congruent musical relations. This quest for invention . . . accounts for the fundamental complexity of Bach’s textures . . . .”6Laurence Dreyfus, “Bachian Invention and Its Mechanisms,” in The Cambridge Companion to Bach, ed. John Butt (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), 173. Respecting Bach’s formal structures, it is more appropriate to examine how musical ideas are treated compositionally, rather than where they occur in pieces.7Dreyfus, 174. In Bach and the Patterns of Invention (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2004), Dreyfus explores Bach’s compositional technique through inventio, specifically, how inventa are treated in non-dance forms. In Bach’s Works for Solo Violin (73), Joel Lester points out some motivic connections, for instance, between the Adagio and Fugue of the G-Minor Solo Violin Sonata, yet he does not reveal any motivic connections between the Sonata’s opening two movements in relation to the last two.

From a philosophical perspective, Karol Berger regards this process as related to Bach’s concept of musical time: “[W]hat matters most to Bach in most of his music, whether vocal or instrumental, is not the flow of time from past to future, beginning to end. Rather, time is either made to follow a circular route or neutralized altogether.”8Karol Berger, Bach’s Cycle, Mozart’s Arrow: An Essay on the Origins of Musical Modernity (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2007), 101. This notion of a circular flow of time, coupled with invention, can be demonstrated in the less contrapuntally demanding Suites and Partitas. Yet, motivic continuity is not only found in the preludes and fugues of the Violin Sonatas, as well as in the keyboard works, but also in the Cello Suites.

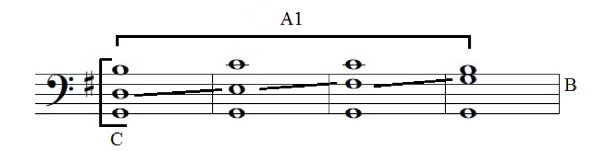

Schoenberg’s Developing Variation

Separated by roughly two hundred years, Schoenberg’s concept of developing variation is similar aesthetically to that of Bach’s inventio. Looking at the Cello Suite in G Major, BWV 1007, through the lens of developing variation illuminates some of the work’s more interesting features. Given that the bass line is the governing structure of Baroque music, the Suite’s motivic elements are present on a macro-harmonic level (both within the first four measures of the Prelude and in the overall harmonic layout of the Suite), and also as individual events in the first measure. As defined by David Beach, there are three types of motives at work in Bach’s Partitas and Suites: (1) the rhythmic motive, (2) the pitch motive, and (3) the voice-leading motive, which is “a pitch motive articulated at successive layers of the voice-leading fabric.”9David Beach, Aspects of Unity in J. S. Bach’s Partitas and Suites: An Analytical Study, Eastman Studies in Music, 1071–9989, vol. 33 (Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press, 2005), 26–30. Accordingly, there are three pitch motives present in the Prelude’s opening four measures: Motive A1, an omnipresent neighboring tone (an inversion of the first lower neighbor, Motive A10I label this lower neighbor Motive A, because it is the first one perceived in the piece. Conversely, Motive A1 functions as a voice-leading motive in the music’s opening.); (2) Motive B, the major tetrachord D–E–F♯–G; and (3) Motive C, the opening tonic harmony, G–D–B (see Example 4). The rhythmic motive, voice-leading motive, and the harmonic design that unifies the Suite will be discussed later in the analysis of the Cello Suite found below.

Example 4. Analytical Reduction, Motives A1, B, and C; Prelude, Cello Suite in G Major, BWV 1007, mm. 1–4

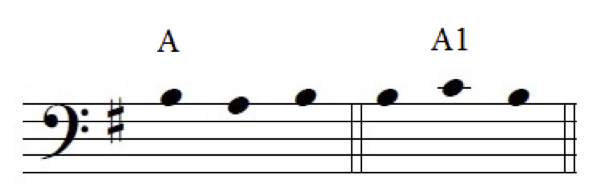

The simplest of the motives is that labeled A (Example 5), the lower neighbor, and given how distilled its features are, risks to be redundant if it is always brought out in a performance. Besides inversion, Bach embellishes it by adding ancillary notes, such as the A pedal in m. 35 of the Prelude (see Example 18 below). It is also displaced to different parts of the beat when compared to its opening presentation.

Example 5. Analytical Reduction, Motives A and A1; Prelude, Cello Suite in G Major, mm. 1–2

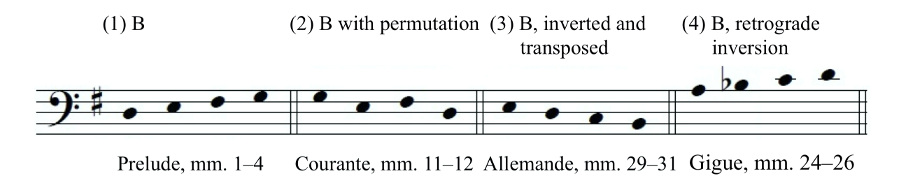

When it comes to its development, Motive B is the most fecund figure in the inventio of the G-Major Cello Suite (see Example 6.1). From its original position, the notes can be rearranged—as in mm. 11–12 of the Courante—to form the couplet figure prominent in many of the movements (Example 6.2). Motive B is also inverted and transposed in mm. 29–31 of the Allemande (Example 6.3) and used in retrograde inversion in mm. 25–26 of the Gigue (see Example 6.4). Motive B operates on two levels, namely, the voice-leading level (from where its function as a pitch motive is derived), where it can act as a bass line and thus be subsumed into the texture, and on the pitch level, where it is featured as the couplet figure or in other guises. All in all, Motive B generates many of the scalar figures present in the piece.

Example 6. Different iterations of Motive B in the Cello Suite in G Major: (1) B, Prelude, mm. 1–4; (2) B, with permutation, Courante, mm. 11–12 (reduced); (3) B, inverted and transposed, Allemande, mm. 29–31(bass-line reduction); (4) B, retrograde inversion, Gigue, mm. 25–26

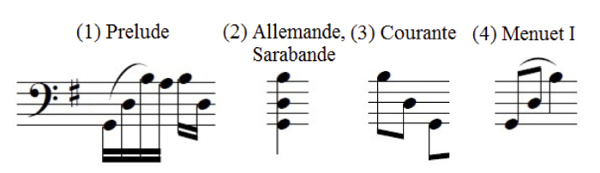

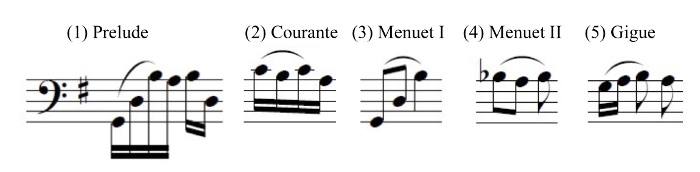

Motive C undergoes rhythmic variation throughout the Suite, with Bach altering its rhythm to fit the character of each dance movement (see Examples 7.1–7.2, 7.4). In the Courante, this motive is inverted (Example 7.3). The motive’s slurred notes, while introduced in the Prelude, are more a gestural idea that influences the articulation of all the motives mentioned above (see Example 8).

Example 7. The different variants of Motive C in the Cello Suite in G Major: (1) Prelude, m. 1; (2) Allemande and Sarabande, m. 1; (3) Courante, m. 1; (4) Menuet I, m. 1

Example 8. Three-note slurred articulation and some examples of its permutation in the Cello Suite in G Major: (1) Prelude, m. 1; (2) Courante, m. 5; (3) Menuet I, m. 1; (4) Menuet II, m. 1; (5) Gigue, m. 3

Cello Suite in G Major, BWV 1007

Prelude

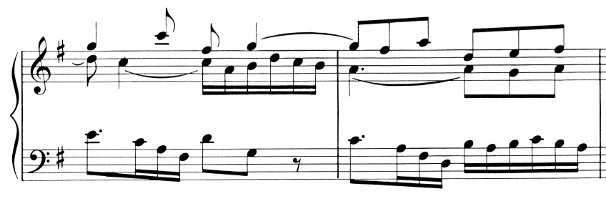

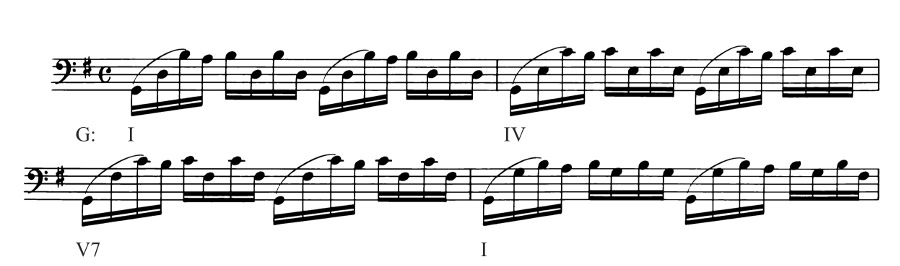

Having provided an overview of how motives work in the Cello Suite in G Major, I shall now turn to a more detailed reading of the piece, beginning with the Prelude. The Cello Suite represents one of the clearest examples of motivic continuity in Bach’s works for solo violin or cello in which all of the ideas present throughout the Suite are expressed initially in the Prelude. The most influential feature of the Suite is the Prelude’s opening harmonic progression in mm. 1–4 over a tonic pedal point: I–IV–V7 –I (Example 9). In all its simplicity, this progression unifies the entire Suite from beginning to end.

Example 9. Opening harmonic progression, Prelude, Cello Suite in G Major, BWV 1007, mm. 1–4

Of equal import is Motive A, the aurally prominent lower-neighbor figure that occurs in m. 1 (see Example 10).11The idea of a lower-neighbor motive seems to be common in Bach’s instrumental music. For instance, the Sixth Brandenburg Concerto (BWV 1051) makes ample use of it throughout its three movements, and it is also a noticeable feature in the C-Minor Prelude and Fugue of the Well-Tempered Clavier, Book 1 (BWV 847). It dominates the texture of the Prelude and returns in subsequent movements. What gives this lower-neighbor figure its motivic function—and distinguishes it from mere ornamentation—is the fact that it alters the otherwise straightforward harmonic progression by its repetition in the arpeggiation figure.

Example 10. Motive A, Prelude, m. 1

While it may seem innocuous, the move to the dominant of D major (in the guise of a secondary dominant or a harmony following a pivot chord in a modulation) in m. 6 is another important harmonic event that marks every movement, whether sufficiently prepared or not, and a significant feature of Bach’s harmonic design in the suite (see Example 11).

Example 11. Move to the Dominant of D Major, Prelude, m. 6

The last two prominent ideas of the Prelude include the descending scales of mm. 29–30 (which inhabit a circle-of-fifths harmonic sequence) and the bariolage (rapid, alternating string crossings) from mm. 31–32 that conclude the movement (see Examples 12 and 13, respectively).

Example 12. Descending scale figures, Prelude, mm. 29–30

Example 13. Bariolage, Prelude, mm. 31–32

Allemande

Bach employs a sonata-style compositional approach in his dance suites, which is made possible by his implementation of durchzuführen and inventio (the working out of ideas).12David Ledbetter explains that Bach’s compositional style is that of the working out (durchzuführen) of ideas (inventio), rather than the spinning out of a melody. He says that “[v]irtually any musical element can constitute an inventio, and this possibility is an important component in the technique of treating dance genres in a sonata manner.” See David Ledbetter, Unaccompanied Bach: Performing the Solo Works (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009), 85. Such an approach creates a layer of complexity in the Allemande that subsumes the motivic material from the Prelude. The Allemande follows a similar harmonic structure to that of the Prelude by a cadence on the tonic in m. 4 and a turn to the relative minor before heading to the dominant. The opening chord—Motive C—mirrors that of the Prelude and whether it is played as a double stop (m. 1) or rolled (m. 9), some iteration of it can be found in the movement. Motive A creates a sense of cohesion in the Allemande by being artfully woven into the texture, connected by flowing scales (see Example 14). There is another connection between the Prelude and the Allemande with respect to the latter’s use of dotted rhythms. This rhythmic pattern is derived from Motive A, if one considers that the first three sixteenth notes, followed by the fourth sixteenth note, create a dotted rhythm, reinforced by the voicing of the gesture (see Example 15).

Example 14. Motive A, Allemande, Cello Suite in G Major, BWV1007, mm. 1–2

Example 15. Derivation of the dotted rhythms in the Allemande from m. 1 of the Prelude

Measures 26–28 foreshadow the Courante through descending eighth notes followed by a flourish of sixteenth notes (also of note is the return of Motive A that leads into each following measure; see Examples 16 and 17, respectively).

Example 16. Foreshadowing of the Courante (with Motive A bracketed) in mm. 26–28 of the Allemande (example begins in m. 24)

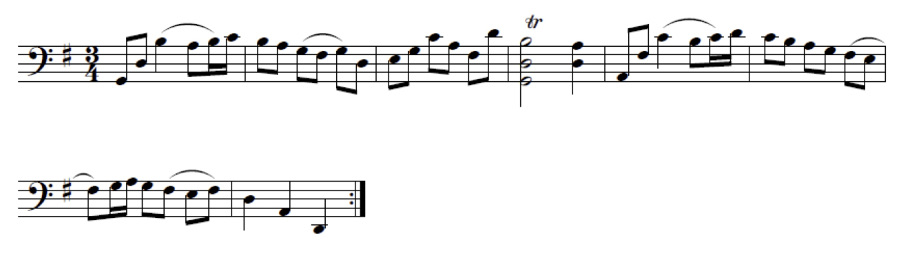

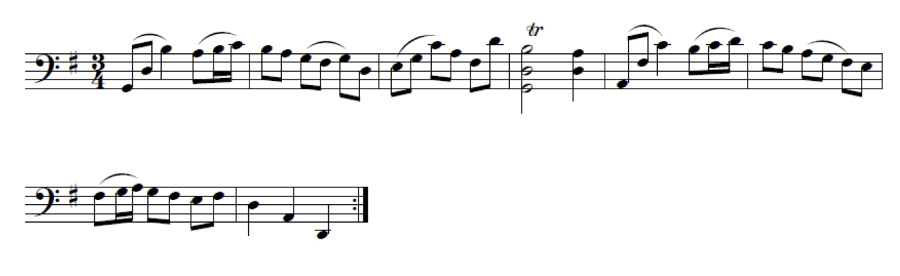

Example 17. Courante, Cello Suite in G Major, BWV 1007, mm. 1–4

Courante

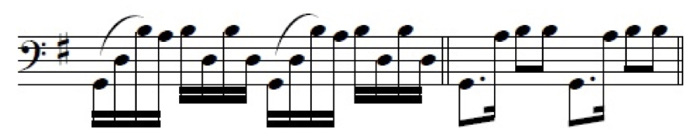

The Courante begins with the Prelude’s opening harmonic progression, I–IV–V. In mm. 5–6, it contains a bariolage variant of Motive A that occurred near the end of the Prelude in mm. 33–35 (see Example 18). Bach inverts the lower-neighbor figure to generate an upper neighbor, Motive A1, beginning in m. 14. This idea comes back in the second half of the binary form. Harmonically, a surprising move to the V7 of D major makes an interesting connection with m. 6 of the Prelude. This connection returns in m. 31, with almost identical figures in both Courante and Prelude (see Example 19).

Example 18. Bariolage variant of Motive A in the Courante (mm. 5–6) compared with that in the Prelude (mm. 33–35)

Example 19. Measure 31 of the Courante compared with m. 6 of the Prelude

Sarabande

The heart of the Suite is the Sarabande. It begins with the Prelude’s opening harmonic progression, with the arpeggiated chords now sounded as triple stops (see Example 20). In this movement, there is almost a conspicuous absence of Motive A. Instead, it relies more on Motive B, along with the opening harmonic progression. In essence, in this piece, Bach employs block chords, and harmonies connected by scalar passages, all overlaid on the music’s harmonic design. The Sarabande is one of the few movements in the Suite where Bach uses polyphonic writing similar to that in his solo violin music. What is more, measure 6.2 is another example of the surprising shift to D major.

Example 20. Opening Chords of the Sarabande, Cello Suite in G Major, BWV 1007, mm. 1–2

Menuet I

Menuet I opens with the germinal harmonic progression. The first five pitches are exactly the same as those in the Prelude; however, their durations have been altered. In what could be perceived as a slowly rolled G-major chord, Bach speeds up time after the stately Sarabande. This spritely Menuet plays with expectations by altering the rhythm of Motive A—usually in the form of a quarter, eighth, and two sixteenths. The gesture of this movement is obvious in relation to the Prelude through the sweep of its opening triad and rearticulation of the lower-neighbor note figure (see Example 21).

Example 21. Opening chords of the Menuet I, Cello Suite in G Major, BWV 1007, mm. 1–4.

The opening notes of the Prelude and Motive A are shown.

Menuet II

Menuet II begins with a stark change of Affect by being cast in the parallel minor key. Its lament bass accompanies Motive A, now sounding at the beginning of mm. 1, 3, 5, and 7. Here, Motive A oscillates between half-steps B♭ and A as well as G and F♯. The lament bass is a variation of Motive B in the Prelude (mm. 1–4; see Examples 4 and 6) where the motive’s ascending tetrachord is now descending and in the minor mode. The bass notes G–F–E♭–D are the foundation of the Menuet’s opening phrase (see Example 22). The B section, mm. 9–24, employs Motives C and A, the latter now recast in B♭ major.

Example 22. Menuet II, Cello Suite in G Major, BWV 1007, mm. 1–4, with the lament bass circled

Gigue

The Gigue is the most enigmatic of the suite’s movements and most directly influenced by the Menuets that precede it. The most interesting feature of the Gigue is its move to G minor (dark clouds in an otherwise sunny sky). This move to the minor mode (namely the B♭ signaled in the preceding movements) could also adumbrate the D-Minor Suite to follow where B♭ serves as an important structural function. While there were only brief intimations of it in the Prelude (mm. 24 and 26), the minor mode is much more intrusive in the Gigue. Here, Bach seems to draw connections with the Courante’s harmonic structure (suspensions and resolutions in mm. 5 and 6, which themselves are related to the falling scales of mm. 29 and 30 of the Prelude). Another element at play in the Gigue is taken from Motive B, a tetrachord that is used as the basis of the melody (see Example 23). Motive B in retrograde inversion also creates the bass line when the music shifts to the minor mode (mm. 24–26; see Example 6.4)

Example 23. Return of Menuet II’s Motive B outline in the Gigue, Cello Suite in G Major, BWV 1007, mm. 9–11 (example starts in m. 6)

In mm. 1–6 of the Gigue, Motive A has now been irrevocably altered, truncated so that there is never a return to its closing note, but a repetition of the second instead. It is as if Bach had lopped off the fourth sixteenth note from what would be a variant of Motive A (see Example 24). Bach also uses Motive A as a bass line and voice-leading motive in the movement. While it appears that Motive A is shortened, he weaves it into the voice-leading texture by using it as the lowest notes of the opening melody (mm. 1–2), as well as later in the piece (mm. 13–16).

Example 24. The first full measure reimagined as a variant of Motive A in inversion.

The end of the Gigue shares a harmonic feature that mirrors the climax at the end of the Prelude. In this instance, Bach employs an interesting bass line ascending primarily in whole steps that is derived from the chromatic scale sounding at the Prelude’s end (see Example 25). It is no coincidence that these events occur in the same location in each movement. By bringing back a variant of this chromatic scale, Bach completes the circle of the G-Major Suite.

Example 25. A reduction of mm. 37–38 of the Prelude compared with mm. 28–32 of the Gigue

Formal and Harmonic Considerations

In the G-Major Cello Suite, the Prelude provides the musical material that serves as the inventio for the following movements, thereby achieving continuity as the Suite progresses from beginning to end. The Prelude’s opening four chords impart significant aural information as to how to interpret the other movements. In one sense, Bach could have written the opening harmonic progression (I–IV–V–I) in half notes, with the indication to arpeggiate the chord (as he does in the Ciaccona for solo violin [Partita, BWV 1004]). Yet he does not, and unlike the Ciaccona, the harmonic structure of the Prelude does not dictate its formal structure, as it does in the Ciaccona.

The arpeggiation in the Prelude creates motion in a movement whose harmonic rhythm is rather slow, much in the way that an Alberti bass would sound. By including the lower-neighbor tone of A, a slight hiccough in an otherwise routine chord progression has resounding implications. Even the opening three notes of the Prelude have a ripple effect that runs throughout the Suite—not one movement is exempt from the G-major triad and its manifold permutations.

Without preludes, the Cello Suites would still exhibit elements of a cohesive form, and their movements would still be intrinsically linked, even if their motivic elements were not exposited beforehand. Similar to an improvisation, Bach primes the listener in the Prelude for the music to follow. Even when there is no Prelude, as is the case with the First and Second Partitas for Solo Violin, Bach still weaves motivic elements throughout a piece.

While the opening harmonic progression unifies the G-Major Cello Suite, the modulation to D major forms another prominent motivic element. Although it is standard procedure to conclude the first half of a binary form in the key of the dominant if the composition is in a major key, how Bach accomplishes this depends upon the piece. In the G-Major Suite, the modulation is typically preceded or announced with a variation on an A-major chord. The exception to this is found in the Menuets, where Bach does not overtly modulate in the A section. However, in the last eight measures of the B section of Menuet I (m. 19), Bach uses A major as a secondary dominant to return to G major via D major. Outside of the Menuets, there are two aural interpretations with respect to this A-major chord: as a secondary dominant indicating a quick return to G major, or as aurally securing the modulation that has already occurred. Typically, what makes this event surprising is how quickly it appears after what would be a common-chord modulation. On the page, it logically makes sense, but as is the issue related to any unaccompanied instrumental work, the imagination of the listener fills out the harmony, and as such, differences of interpretation abound. Michael Baker explores this idea of tonal ambiguity and perception in the Cello Suites through the premise of a tonal pun that occurs when a listener’s expectations diverge in ambiguous areas (namely after repeats in minor-mode movements).13Michael Baker, “A Curious Type of ‘Tonal Pun’ in Bach's Suites for Unaccompanied Cello,” Indiana Theory Review 27, no. 1 (Spring 2009), 7. The expectation of what is to come is supplanted by what sounds like an unexpected harmonic event.14Although not within the scope of this article, it should be noted that this issue of listener expectation plays a key role in the field of music cognition and perception. The first cadence in the Courante (m. 8)—while it is not an example of a Baker tonal pun—is an apt example of an ambiguous moment where the listener’s expectations are denied; the resolute G-major cadence, which primes what would be a new phrase in G major, is quickly turned on its head by the move to the A-major harmony in m. 9.15This article deals primarily with melodic motivic material, given that others have covered how Bach’s harmonic plans structure a work. See Ledbetter’s Performing Unaccompanied Bach, chap. 4, 176–237.

Example 26. The Courante’s move to D major in m. 9

Beyond this harmonic motion of a secondary dominant, there is yet another element at play: Bach’s use of schemata to unify a composition. Robert Gjerdingen’s work on schemata theory and the Galant Style demonstrate another layer of Bach’s compositional process that underlies his use of motives which unify the Suite.16Robert Gjerdingen, Music in the Galant Style (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007). Gjerdingen’s Quiescenza schema is at the heart of the G-Major Cello Suite, and which at its core is made up of the scale degrees  –

– –

– –

– over a tonic pedal.17Coincidently, Rodolphe Kreutzer’s 13th Étude (from his 42 Études ou Caprices, 1796) opens with the Quiescenza schema arpeggiated exactly like the Prelude of the G-Major Cello Suite (without the lower neighbor tone—Kreutzer stays within the harmony). Gjerdingen explains: “Early in the eighteenth century, the traditions of extemporized preludes . . . called for an opening passage that would, like an expanded cadence, move toward the subdominant . . . and then toward the dominant before returning to the tonic.”18Gjerdingen, 182. By the mid-eighteenth century, however, the Quiescenza’s opening role shifted to that of an ending structure.19Gjerdingen, 183. If the schema represents the background structure (that is, the scaffolding), motives are highlighted by how they disrupt this structure, with the lower neighbor disrupting the Quiescenza schema. Alongside this opening Quiescenza gambit, the move to E minor and the dominant of D major (A major) also serve as foundational pillars of the harmonic plan upon which Bach bases each movement of the Suite.

over a tonic pedal.17Coincidently, Rodolphe Kreutzer’s 13th Étude (from his 42 Études ou Caprices, 1796) opens with the Quiescenza schema arpeggiated exactly like the Prelude of the G-Major Cello Suite (without the lower neighbor tone—Kreutzer stays within the harmony). Gjerdingen explains: “Early in the eighteenth century, the traditions of extemporized preludes . . . called for an opening passage that would, like an expanded cadence, move toward the subdominant . . . and then toward the dominant before returning to the tonic.”18Gjerdingen, 182. By the mid-eighteenth century, however, the Quiescenza’s opening role shifted to that of an ending structure.19Gjerdingen, 183. If the schema represents the background structure (that is, the scaffolding), motives are highlighted by how they disrupt this structure, with the lower neighbor disrupting the Quiescenza schema. Alongside this opening Quiescenza gambit, the move to E minor and the dominant of D major (A major) also serve as foundational pillars of the harmonic plan upon which Bach bases each movement of the Suite.

The harmonic scheme of the G-Major Cello Suite, including the Quiescenza schema, and how Bach uses it as a unifying plan, are integrated with pitch and voice-leading motivic development that anticipates the techniques of future composers. While not necessarily operating under the same principles of musical rhetoric as Bach did, later generations also integrated harmonic plans, voice-leading techniques, and motivic material when composing a work. For example, the harmonic plan of Schubert’s “Der Erlkönig” (D. 328) is derived from the piano’s bass line, opening scale, and arpeggiated figure.20Charles Burkhart, “Schenker’s ‘Motivic Parallelisms,’” Journal of Music Theory 22, no. 2 (Autumn 1978), 157–60. Although it may be expected for certain key areas to occur within a binary form (such as the dominant or the submediant), it is no coincidence that Bach turns to or borrows from the parallel minor in five of the seven movements (the exceptions being the Sarabande and the first Menuet) of the G-Major Suite.21Given the da capo form of the Menuets, it may be more prudent to say five of the six movements. Compared to the G-Major Partita, the G-Major Suite tends toward the “flat” minor keys, A minor and G minor, whereas the Partita’s trajectory leads consistently toward E minor and B minor.22Although the G-Major Partita does use the parallel minor near the end of the Prelude, it does not return in the rest of the work. Whenever Bach uses a flat (Bb or Eb), it is in the context of a fully diminished seventh chord in the following movements.

This use of an overarching harmonic plan to connect a multimovement work reverberates throughout the common practice period, especially in the works of Austro-Germanic composers.23In Aspects of Unity in J. S. Bach’s Partitas and Suites (19–22), Beach examines Bach’s large-scale harmonic plan for the Cello Suite in C Major Suite, BWV 1009. The repertoire is replete with examples, and one could cite Mozart’s C Major Piano Concerto No. 21, K. 467, whose move to A♭ major in the second half of the first movement adumbrates the recapitulation of A♭ major in the main theme of the second movement.24The move to G minor in the first movement also has repercussions throughout the rest of the concerto. In Beethoven’s String Trio in C Minor (Op. 9, no. 3), the harmony is pulled toward more remote flat keys, with E♭ minor coloring the second theme of the first movement and returning in the same location (the second theme) in the last movement.

Performance Considerations

For the performer of the G-Major Cello Suite, knowing its motives can assist him or her to develop insightful interpretations. Specifically, bowing Motive A as a slurred group of three notes could dramatically alter what elements a listener perceives, especially since expressivity is the domain of the bow (and thus right-hand articulation) in Baroque performance practice. But the difficulty arises when artistic expression dissolves into pedantry. For example, by grouping every lower-neighbor figure as a three-note slur, a performer could easily ruin the music. Menuet I provides a good illustration of this scenario (see Example 27):

Example 27. Slurs altered to follow Motive A in Menuet 1, mm. 1–8

In this instance, the Menuet’s emphasis on beat 1 would be altered by slurring the lower-neighbor motive on beats 2 and 3. Therefore, the performer must create a hierarchy based on different motivic and musical elements, that is, whether it is valuable to highlight Motive A, or the opening G–D–B gesture. Coupled with the knowledge of these Baroque dances, this would inform his or her interpretation. Personally, my reading would be closer to this:25I would not necessarily slur Motive A in m. 7 in order to bring out the cadence. In m. 6, I may change to a couplet slurring on beats 1 and 2 and separate the last eighth notes for contrast on the repeat.

Example 28. The author’s interpretation highlighting Motive A in Menuet I, mm. 1–8, as well as the three-note opening gesture from the Prelude

Conclusion

While the idea of a motive, as it is thought of now, may not have been in common parlance in Bach’s time, his treatment of inventio—that is, how he develops and integrates motivic material (voice-leading motives, pitch motives, rhythmic motives, harmonic outline) in a work—creates a motivic continuity in the Solo Suites and Partitas that would strongly influence compositional technique in the later Classical and Romantic eras. Though focusing on motives in this article, I may seem counterintuitive or reductionist in crafting an overarching narrative of the solo instrumental music of Bach. But by discovering and bringing out these motivic relationships, I argue that performers can create interpretations that transcend the idea of approaching instrumental music of the Baroque as only unified by Affect and key.

Notes

1. Arnold Schoenberg, Fundamentals of Musical Composition (London: Faber and Faber, 1967), 8.

2. Jan Swafford, Beethoven: Anguish and Triumph (New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2014), 939. Swafford describes das Thema as “the all-important opening theme that sets the mood, the leading motifs from which other themes will be made, and the general direction of the whole piece.”

3. The recital was given by pianist Stephen Beus at Riceland Hall in Jonesboro, Arkansas, on February 20, 2017. There currently seems to be more flexibility in programming Bach’s solo instrumental works, which may harken back to the past. With respect to the Sonatas and Partitas for violin, Zay David Sevier notes that during the rediscovery of Bach’s music in the nineteenth century, the Solo Violin Sonatas were not performed in their entirety, nor were they performed without accompaniment; see Zay David Sevier, “Bach’s Solo Violin Sonatas and Partitas: The First Century and a Half, Part 2,” Bach 12, no. 3 (July 1981): 21–29. Even in the early twentieth century, violinists such as Fritz Kreisler (1875–1962) would rarely program an entire Bach Sonata or Partita on a recital program.

4. The Prelude of the G-Major Partita shares an interesting feature with its Gigue, in that both movements prominently feature rests as part of the construction of their opening gestures.

5. See Joel Lester, Bach’s Works for Solo Violin: Style, Structure, Performance (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999), 42; David Schulenberg, The Keyboard Music of J. S. Bach (New York: Schirmer Books, 1992), 151; and Vincent P. Benitez, “Musical-Rhetorical Figures in the Orgelbüchlein of J. S. Bach,” Bach 18, no. 1 (January 1987): 3–6. Johann Mattheson (1681–1764) is noted for his writings regarding the connections between rhetoric and music, particularly involving the structure of a musical oration in Der vollkommene Capellmeister (1739). See Johann Mattheson, Der vollkommene Capellmeister (Hamburg: Christian Herold, 1739); trans. Ernest C. Harriss as Johann Mattheson’s Der vollkommene Capellmeister: A Revised Translation with Critical Commentary (Ann Arbor: UMI Research Press, 1981), 469–72.

6. Laurence Dreyfus, “Bachian Invention and Its Mechanisms,” in The Cambridge Companion to Bach, ed. John Butt (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), 173.

7. Dreyfus, 174. In Bach and the Patterns of Invention (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2004), Dreyfus explores Bach’s compositional technique through inventio, specifically, how inventa are treated in non-dance forms. In Bach’s Works for Solo Violin (73), Joel Lester points out some motivic connections, for instance, between the Adagio and Fugue of the G-Minor Solo Violin Sonata, yet he does not reveal any motivic connections between the Sonata’s opening two movements in relation to the last two.

8. Karol Berger, Bach’s Cycle, Mozart’s Arrow: An Essay on the Origins of Musical Modernity (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2007), 101.

9. David Beach, Aspects of Unity in J. S. Bach’s Partitas and Suites: An Analytical Study, Eastman Studies in Music, 1071–9989, vol. 33 (Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press, 2005), 26–30.

10. I label this lower neighbor Motive A, because it is the first one perceived in the piece. Conversely, Motive A1 functions as a voice-leading motive in the music’s opening.

11. The idea of a lower-neighbor motive seems to be common in Bach’s instrumental music. For instance, the Sixth Brandenburg Concerto (BWV 1051) makes ample use of it throughout its three movements, and it is also a noticeable feature in the C-Minor Prelude and Fugue of the Well-Tempered Clavier, Book 1 (BWV 847).

12. David Ledbetter explains that Bach’s compositional style is that of the working out (durchzuführen) of ideas (inventio), rather than the spinning out of a melody. He says that “[v]irtually any musical element can constitute an inventio, and this possibility is an important component in the technique of treating dance genres in a sonata manner.” See David Ledbetter, Unaccompanied Bach: Performing the Solo Works (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009), 85.

13. Michael Baker, “A Curious Type of ‘Tonal Pun’ in Bach's Suites for Unaccompanied Cello,” Indiana Theory Review 27, no. 1 (Spring 2009), 7.

14. Although not within the scope of this article, it should be noted that this issue of listener expectation plays a key role in the field of music cognition and perception.

15. This article deals primarily with melodic motivic material, given that others have covered how Bach’s harmonic plans structure a work. See Ledbetter’s Performing Unaccompanied Bach, chap. 4, 176–237.

16. Robert Gjerdingen, Music in the Galant Style (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007).

17. Coincidently, Rodolphe Kreutzer’s 13th Étude (from his 42 Études ou Caprices, 1796) opens with the Quiescenza schema arpeggiated exactly like the Prelude of the G-Major Cello Suite (without the lower neighbor tone—Kreutzer stays within the harmony).

18. Gjerdingen, 182.

19. Gjerdingen, 183.

20. Charles Burkhart, “Schenker’s ‘Motivic Parallelisms,’” Journal of Music Theory 22, no. 2 (Autumn 1978), 157–60.

21. Given the da capo form of the Menuets, it may be more prudent to say five of the six movements.

22. Although the G-Major Partita does use the parallel minor near the end of the Prelude, it does not return in the rest of the work. Whenever Bach uses a flat (B♭ or E♭), it is in the context of a fully diminished seventh chord in the following movements.

23. In Aspects of Unity in J. S. Bach’s Partitas and Suites (19–22), Beach examines Bach’s large-scale harmonic plan for the Cello Suite in C Major, BWV 1009.

24. The move to G minor in the first movement also has repercussions throughout the rest of the concerto.

25. I would not necessarily slur Motive A in m. 7 in order to bring out the cadence. In m. 6, I may change to a couplet slurring on beats 1 and 2 and separate the last eighth notes for contrast on the repeat.

References

Baker, Michael. “A Curious Type of ‘Tonal Pun’ in Bach’s Suites for Unaccompanied Cello.” Indiana Theory Review 27, no. 1 (2009): 1–21.

Beach, David W. Aspects of Unity in J. S. Bach’s Partitas and Suites: An Analytical Study. Eastman Studies in Music, 1071–9989, vol. 33. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press, 2005.

Benitez, Vincent P. “Musical-Rhetorical Figures in the Orgelbüchlein of J. S. Bach.” Bach 18, 1 (January 1987): 3–21.

Berger, Karol. Bach’s Cycle, Mozart’s Arrow: An Essay on the Origins of Musical Modernity.

Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2007.

Burkhart, Charles. “Schenker’s ‘Motivic Parallelisms.’” Journal of Music Theory 22, no. 2 (Autumn 1978): 145–75.

Dreyfus, Laurence. “Bachian Invention and Its Mechanism.” In The Cambridge Companion to

Bach, edited by John Butt, 171–92. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

———. Bach and the Patterns of Invention. Cambridge. MA: Harvard University Press, 2004.

Gjerdingen, Robert O. Music in the Galant Style. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Ledbetter, David. Unaccompanied Bach: Performing the Solo Works. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009.

Lester, Joel. Bach’s Works for Solo Violin: Style, Structure, Performance. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999.

Mattheson, Johann. Der vollkommene Capellmeister. Hamburg: Christian Herold, 1739. Translated by Ernest C. Harriss as Johann Mattheson’s Der vollkommene Capellmeister: A Revised Translation with Critical Commentary. Ann Arbor: UMI Research Press, 1981.

Schoenberg, Arnold. Fundamentals of Musical Composition. London: Faber and Faber, 1967.

Schulenberg, David. The Keyboard Music of J. S. Bach. New York: Schirmer Books, 1992.

Sevier, Zay David. “Bach’s Solo Violin Sonatas and Partitas: The First Century and a Half, Part 2.” Bach 12, no. 3 (July 1981): 21–29.

Swafford, Jan. Beethoven: Anguish and Triumph. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2014.

Warwick, Cole. “Improvisation as a Stimulus to Composition in Bach’s Partita II.” Bach 31, 1 (2000): 96–112.

Winold, Allen. Bach’s Cello Suites: Analyses and Explorations. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2007.

Scores

Bach, Johann Sebastian. Sechs Suiten für Violoncello solo: BWV 1007–1012. Edited by Hans Eppstein. Neue Ausgabe sämtlicher Werke-Johann Sebastian Bach. Kammermusikwerke, Band 2. Kassel: Bärenreiter Verlag, 1988–91.

———. Sechs Partiten: Erster Teil der Klavierübung: BWV 825–830. Edited by Richard Douglas P. Jones. Kassel: Bärenreiter, No. 5152, 1976.

———. Englische Suiten. 1–3: BWV 806–808. Edited by Rudolf Steglich. Munich: G. Henle Verlag, 1971.