Abstract

Frederick Lau and Christine Yano’s edited work Making Waves (2018) notes that while music travels from culture to culture, “There is always a backstory behind each movement . . . [.] [A]ny piece of music or an instrument can become [a resource that enables] social actors to construct, shape, and imagine appropriate meanings for the context” (Lau and Yano 2018, 2). In 1990, the Scottish Chamber Orchestra (SCO)—in conjunction with several other local governing bodies in Glasgow, Scotland—commissioned a set of Javanese gamelan instruments from Pak Suhirdjan in Yogyakarta. This began a now twenty-nine-year project of gamelan music creation, performance, and social work in Scotland’s largest city. While exoticism remains a trope of Western use of non-Western musics and instruments, the history of gamelan in Scotland provides intriguing examples through which to explore this trope. The difference afforded by the instruments and sound was initially deemed pivotal to the gamelan’s success in Glasgow. At the same time, however, the SCO and others also wanted to make use of the gamelan’s participatory nature in order to create inclusive workshops and programs for people with special needs. Thus, the exoticness of Javanese gamelan was used to further the goal of local community-based, participatory musicking. This article explores the backstory of Javanese gamelan in Glasgow; the impetus that inspired city organizers to embrace, shape, and imagine the local potential of distant musical traditions; and some implications of those imaginings.

Vincent Benitez

Introduction

Yearning strains of bagpipe against a backdrop of pelog. Sweet, somber trills of the “Scotch snap” with slenthem. Elderly, shaking, and confused hands clasping kenong mallets and making music. All these things, and more, are gamelan in Glasgow.

In the book Making Waves, ethnomusicologist Frederick Lau and anthropologist Christine Yano note that when music moves from culture to culture, “There is always a backstory behind each movement . . . [.] [A]ny piece of music or instrument can become [a resource that enables] social actors to construct, shape, and imagine appropriate meanings for the context” (Lau and Yano 2018, 2). This conceptualization of backstory is useful for the exploration and explanation of gamelan use in Glasgow, Scotland. In 1990, the Scottish Chamber Orchestra (SCO), the Strathclyde Regional Council (SRC), and particularly the SRC’s Social Work Department (SWD) commissioned a set of Javanese gamelan instruments from Pak Suhirdjan in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. Thus began a now thirty-year project of gamelan instrument use in Glasgow, Scotland.

The purchase of these instruments not only stemmed from an idea of what gamelan was but also what it could be. It is an idea imagined to be both exotic and practical, what Maria Mendonça has called a “succession of ‘exoticisms’” (Mendonça 1993, 19). Although the exoticization of non-Western cultures remains a trope of Western globalization, the backstory of gamelan in Scotland provides intriguing examples by which one can explore this trope. In this article, I examine the impetus that inspired Glaswegian city organizers to embrace, shape, and imagine the local potential of distant musical traditions. One of the main goals of the SCO, SRC, and SWD was to use their gamelan to benefit people with special needs. In so doing, they capitalized on the physical and practical uses of a Javanese gamelan in Scotland, but they also invented the reality of a Scottish gamelan. I argue that understanding backstories like these helps ethnomusicologists—like myself—and other music scholars gain better insights into the complex experiences of cultural appropriation.

A Brief Explanation of Gamelan

As a frame of reference, the following is a brief description of central Javanese gamelan instruments and their uses within Javanese culture. The complexities of the gamelan ensemble and its music have taken up whole volumes on their own. My reasoning for including these terms and concepts are twofold: (1) to provide context for readers who may not be familiar with Javanese gamelan, and (2) because they form the basis (and most basic) of knowledge that Scottish organizers knew when first purchasing their gamelan instruments. It was upon this foundation—particularly the wide variety of percussion instruments, communal involvement, and perceived lack of a clear leader—that the SCO, the SRC, and the SWD built their plan for a Scottish gamelan.

The word “gamelan” means to hit or to strike and—like the word “orchestra”—refers to a collection of (named) instruments. The ensemble itself is composed of fifteen to thirty, mostly percussion (idiophone and membranophone) instruments. The bulk of the instruments are metallophones (various saron, slenthem, and gender), hanging gongs (gong ageng and kempul), and kettle gongs (kenong, kethuk, and bonang). Other instruments include drums (kendhang and ciblon), xylophone (gambang), string instruments (rebab and siter), and flutes (suling).

Slendro and pelog refer to the two tuning systems found in Java and Bali. Pelog has seven pitches with nonequidistant intervals; slendro has five pitches with roughly equidistant intervals.1This has been debated and indeed, Martopangrawit writes: “In one gembyangan of laras sléndro there are five tones, which can be considered to have equal intervals between them. . . . If we read (sing) the sléndro tones in order, from low to high, or vice versa, and listen to them carefully, we will find both large and small intervals between them” (Martopangrawit 1984, 44). A full Javanese gamelan includes instruments in both tuning systems (for example: four saron tuned in pelog and four saron tuned in slendro).

Gamelan is exceedingly communally based and participatory. The drummer and rebab player act as conductors, but they do not stand out from the rest of the ensemble. When singers are present, their voices provide an added texture to the overall performance, and the instruments do not fall into an accompanying role. Each musical part is dependent on each other part, so listening and cooperation are key.

In Java, these instruments were traditionally kept at the kraton (palace) and often played in a pendhåpå (open air pavilion). Today, while some ensembles can still be found in the kraton, others are housed at universities, conservatoires, villages, and radio stations. The ensembles were used for various rituals and ceremonies, to accompany wayang kulit (shadow puppetry) and wayang wong (dance theater that features human dancers), and, after the introduction of radio, as “kleneng(an)” or for pleasure listening outside the context of dance or theater,2From Richard Pickvance’s A Gamelan Manual 2005. although this was quite rare in Java up until recently. Although gamelan music and playing were not typically used for work with patients with special needs in Indonesia, music therapist Dr. Helen Loth was recently invited to the Conservatory of Music of the Universitas Pelita Harapan in Tangerang, Java to introduce her methods for using gamelan in therapy (Conservatory of Music (CoM) UPH 2016).

The Backstory of Gamelan in Scotland

For a complete picture of the backstory of this Scottish gamelan, it is also necessary to see the context in which it was purchased. The 1980s was a flourishing time for gamelan in England. The University of York purchased their gamelan, Kyai Sekar Patak, in 1981. The Oxford Gamelan Society, the oldest community gamelan in the United Kingdom, was founded in 1985. And the London-based Southbank Gamelan Players got started in 1987, just to name a few. Mendonça recorded the existence of at least 80 gamelans in the United Kingdom (Mendonça 2002), but the vast majority of these ensembles are based in England.3The current Cultural Attaché to the Indonesian Embassy in London, Pak E. Aminudin Aziz, has told me that there are probably 45 current active groups in the UK. This may not count ensembles that are not currently active or those that meet or perform sporadically.

By contrast, Scotland has five sets of gamelan instruments: (1) Spioraid an dochais (Spirit of Hope) owned by the city of Glasgow (acquired in 1990); (2) Kyai Sekar4Also spelled Seker. Sumarsono Milis (Spirit of the Sweet Flower) owned by the University of Edinburgh (unclear when acquired); (3) Northern Gamelan, a Balinese Gamelan Gong Kebyar owned by the University of Aberdeen (acquired in 1992); (4) a bronze set of Javanese gamelan instruments owned privately (acquired in 1992); and (5) a set of Balinese angklung instruments funded by the Shetland Islands’ Council Education Department (acquired in the 1990s).

Of these five sets, only Spirit of Hope has been used continuously since its arrival in Scotland. It was, therefore, the focus of my initial inquiry when I started fieldwork there in 2014. The two sets owned by universities are only in use when a tutor or gamelan specialist is available to teach courses or lead workshops. The privately owned gamelan instruments were used in a middle school, and since retiring, their owners have considered continuing workshops for children. While the Balinese angklung instruments in Shetland have not been used for several years, their custodian, Michael Blythe, was planning to start a primary school gamelan project in October 2019. Thus, the focus of these gamelan ensembles in Scotland has been on education rather than strictly performance, and Spirit of Hope was originally intended not only for general education but also for work in special needs communities. Therefore, let us focus attention on this gamelan’s backstory.5I am planning future research that will focus on these other gamelans, particularly the angklung set.

Spirit of Hope’s presence in Glasgow can be traced back, as early as 1985, to pioneering work initiated by Ian Ritchie—then managing director of the SCO. Ritchie was interested in cultivating educational and social programs with his orchestra, and it was through this development work that the SRC became involved. Although now defunct, the SRC was at one time the largest local authority in Europe and was responsible for educating almost half of Scotland’s children (p.c. Ian Ritchie, October 14, 2015).

In 1986, Glasgow was designated the 1990 “European City of Culture.” The SRC and the City of Glasgow District Council took on certain responsibilities for planning and funding a year-long event that would include many different musical, artistic, and cultural performances. From nearly the beginning of planning, the SRC also intended to include ways for various socially underprivileged populations to participate and to be acknowledged: “[The SRC’s] involvement will be particularly strong in the educational and social work fields by allowing communities and disadvantaged groups to have the opportunity to enjoy and participate in cultural activities” (Calderwood 1988, 3). The SRC’s policy was ultimately concerned with quality of life, support for and promotion of the arts, availability of the arts, wider use of the arts and culture as tools for education, and particularly the use of arts and culture “as a medium of self-development amongst the disabled, the elderly and other special needs groups” (Calderwood 1988, 3).

Ritchie, along with Chris Jay, then deputy head of the SRC’s Social Work Department, believed that a set of gamelan instruments would be ideal for the majority of the SRC’s goals concerning the 1990 Year of Culture and beyond. Ritchie explained his ideas concerning the appropriateness of gamelan, particularly for people with special needs:

Because at this point, I completely understood that the gamelan, more than a classical orchestra—much more than that—a gamelan was the perfect mechanism for inclusion in music making. It is the most socially inclusive . . . collection of instruments you could find as an ensemble because if you have special needs and you have only a limited amount of movement or skill, you can still be slowly hitting a gong . . . The more dexterity, the more experience you have, the more you’re dealing with the more virtuosic part of the orchestra. It seemed to me to be simultaneously inclusive of all different levels of ability and everybody had the full opportunity to be stretched. I felt it’s a sort of marvelous democratic set up, the gamelan, and there was, therefore, great opportunity for people with learning difficulties, with special needs, to actually use a gamelan and feel part of something, an essential, crucial part of something: making music together. (p.c. Ian Ritchie, October 14, 2015)

Jay also noted that, “[Gamelan is] specially [sic] suitable for the development of mental/physical coordination and group co-operation, and should be specially [sic] appealing to students in our adult training centres” (Jay 1990).

In December 1990, the then-nameless (see below) gamelan instruments arrived in Scotland. The slendro half of the instruments were housed at Motherwell College for a time before being taken to the Murray Owen Centre in East Kilbride. The pelog half of the instruments were initially taken to the Hanson Street Adult Training Centre in Glasgow’s East End. After that, the pelog instruments lived in various places, including an old Chamber of Commerce building, the Clyde Theatre, the Washington Street Theatre, Tramway, and finally Campbell House at Gartnavel General Hospital. This separation “at birth” (p.c. Ian Ritchie) of the two tuning systems was in keeping with Jay’s plans for accessibility, accommodation, and use. In a 1991 memorandum to his colleagues, he noted, “subject to proper safeguards, the gamelan should be played as much and as often and . . . by as wide a range of people as possible.”

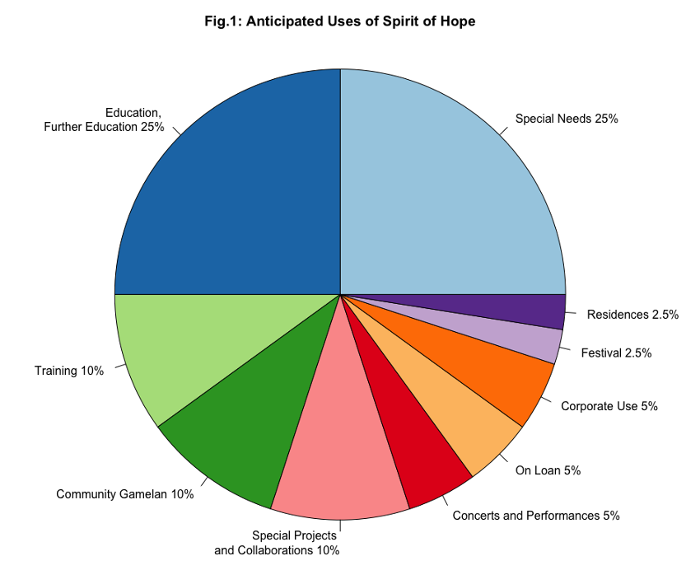

Figure 1. Pie chart delineating how the gamelan instruments were to be used

The pie chart in Figure 1 shows Ritchie and Jay’s planned breakdown of how the instruments would be used, with a full fifty percent divided equally between (further) education and work with special needs groups. So important was this work that as early as 1992, a “Proposal for an Indonesian Pilot Study in the Creation and Development of a Special Needs Integrated Music Production Company” was submitted. This project would have involved Mrs. Suyono of the Indonesian Embassy in London, the Strathclyde Regional Council, and Strathclyde Orchestral Productions (SOP). At the time, the SOP was working on a

long term plan to use the Gamelan in various professional and community productions. The Gamelan is a unique orchestra in that it creates scope for the development of musicians and individuals with learning difficulties and physical mobility problems, enabling an interaction hitherto unseen in the western world. (Proposal for an Indonesian Pilot Study 1992)

At the same time, cultural officials at the Indonesian embassy apparently approached the SOP regarding development of an analogous program in Indonesia. The SOP noted that

[w]e are obviously interested in pursuing links and ties of this kind. However, we feel that in order to create a project that caters [to] the specific needs of Indonesia, a pilot study and development programme would be the best way forward. There is always a danger that in advising and encouraging a nation to develop another country’s policies[,] a system of colonisation is created[,] and we feel this should be avoided at all costs. (Proposal for an Indonesian Pilot Study 1992)

In their desire to create a professional performing group that supported musicians with special needs and that utilized gamelan, the SOP was nonetheless aware that this kind of work did not have a parallel in Java. The accessibility imagined to already exist within Javanese gamelan by these organizers was nevertheless found to be unique in its use in Scotland and did not impose on any other culture. Thus, the gamelan’s accessibility and its use with special needs participants—either in adult training centers, city-organized workshops, or for a professional, integrated performing company—were resources that supported SCO, SRC, SWD, and SOP policies and programs.

This approach was not without its critics, however. UK composer and gamelan tutor Adrian Lee voiced “some critical observations” of the Scottish gamelan project in 1991.6Lee’s observations are actually dated May 1990. I believe this was mislabeled as Lee was hired to teach gamelan and lead workshops in Glasgow from March to May 1991. His observations also begin with the phrase, “Since the acquisition of the gamelan,” which took place in December 1990. Because it would have been difficult for him to criticize a gamelan program that was not in place in May 1990, I feel relatively confident he just got the year wrong. In contrast to Jay’s designs, Lee wrote that it was “altogether an unhealthy sign that the gamelan has not been played as a complete set since its arrival in Scotland” (Lee 1991, 2). Also, it was his “strong recommendation to advise against an ‘open access’ policy – whereby instruments can be hired without the necessary proper supervision and guidance” (Lee 1991, 3). Although Lee’s own work with Disabled7In his article, Adrian Lee capitalized the word “Disabled” when referencing people. This is a trend that seeks to empower previously disempowered groups, so I continue it here. musicians acknowledges the power that music can have in anyone’s life, he was critical of the specific methods by which Scotland was introducing gamelan to its people. There was a distinct difference between what Scottish organizers planned for their gamelan and Lee’s perception of the correct or “healthy” way to use these instruments. Ethnomusicologists, musicians, and other music scholars have voiced concerns regarding changing traditional Javanese gamelan practices when these instruments move to new countries.8See, for example, https://www.wbur.org/artery/2014/07/19/boston-gamelan-music. However, Lee and many others have also argued for the positive effects that music has on quality of life for people with special needs.9Lee is, of course, not alone. Within the last few decades, Disability Studies have intersected with musicology and popular music studies to examine music’s use with adults and children with special needs, as well as music’s relation to disability as a social and cultural construction. See, for example, Balensuela 2019, Howe et al. 2016, Williams 2013, Lerner and Straus, eds., 2006, and Lubet 2006. The seeming contradiction of Lee’s position exemplifies the concerns ethnomusicologists have regarding the exoticization of non-Western musical traditions as well as musical and cultural appropriation.

Javanese Gamelan (and Exoticism) as a Resource to Construct, Shape, and Imagine a Scottish Gamelan

Sumarsam has asked, “[D]oes gamelan represent ‘the strange Orient,’ ‘exotic Otherness,’ or an object made ‘strangely familiar’? The answer is all of the above” (Sumarsam 2013, 78). Both familiarity and difference were crucial to the success of gamelan in Scotland. One major goal of the SCO and the SWD was to use the participatory nature of gamelan to create inclusive workshops and programs for marginalized people. But it was the exoticness of Javanese gamelan that they leveraged to get people to participate. In conversation, Ritchie emphasized that the gamelan’s difference from a Western ensemble is part of what made it attractive. The unique look and the sound of the instruments were often emphasized. Additionally, in anticipation of the gamelan’s arrival in Scotland, press coverage in 1990 referred to the gamelan sounds as “jungle drums” and “ancient instruments.”10The SCO and the SRC did not necessarily contribute these ideas or this language themselves, but the enticing description of music of the Other, which was intended to arouse curiosity, certainly did not hurt them in terms of encouraging participants.

Mendonça noted how the “‘strangeness’ of the gamelan, rather than confining and inhibiting musical development, can be a liberating characteristic, acting as a means of accessing musical experience” (Mendonça 1993, 11). Helen Loth explains how the “‘alien’ nature of the [gamelan] music . . . rather than putting participants off, was a strength because it served to make everyone equal” (Loth 2014, 50). Related to these ideas but taking a slightly different approach, Raymond MacDonald and Dorothy Miell describe how the gamelan’s “relative obscurity within Western cultures makes it an ideal instrument for use with special needs populations as individuals can approach the Gamelan, as both listeners and performers, without any preconceived cultural stereotypes” (MacDonald and Miell 2002, 166). Ian Ritchie was clearly thinking along these lines when he described his vision of how gamelan could be used in Scotland.

But difference was not enough; in other words, there had to also be elements in which familiarity was woven. Therefore, the Scottish organizations and their representatives found ways to connect the gamelan instruments themselves to Scotland, but they did this in ways that also interacted with or supported Javanese instrumental practices. There are three important properties of each set of gamelan instruments: their look, their name, and their sound.11For the purposes of this article, I am choosing to focus on these three components. With some general exceptions, these properties are unique to each gamelan and serve as the instruments’ main identifiers. For Glasgow’s gamelan, each of these properties is or has been tied specifically to Scotland.

The Look

Figure 2. Map of Scotland, organizational initials, and thistle carved on the slenthem

Figure 3. Kendhang with Scottish carvings

Figure 4. Bonang stand with Scottish carvings

Amongst the gold-filigreed leaves, each dark, reddish-brown instrument case displays a map of Scotland; the initials of the SCO, SWD, and the SRC; and a thistle (see Figures 2, 3, and 4). The map may seem at first glance to be the most overt connection to Scotland as it stylistically shows both the Scottish mainland and western isles. Next, the initials of the various organizations that funded and supported the instruments also make direct connections to the gamelan’s host country. It is the image and story of the thistle, however, that has become part of this gamelan’s narrative and remains a part of its history.

The thistle is the national flower of Scotland and a powerful symbol of resistance and identity. According to legend, the thistle protected the Scots from invading Norsemen in the 1260s. The image of the thistle was used on silver currency starting in 1470, and the Order of the Thistle was established in 1540 by King James V (Johnson). There are no thistles in Indonesia, however, so the SCO sent a free-hand drawing of Onopordum acanthium to the Javanese instrument makers. Ritchie noted a story regarding another gamelan he had seen in South London, also made by Pak Suhirdjan. This London gamelan also featured thistles, but Ritchie noted:

. . . this South London authority . . . probably to this day . . . [does not] quite understand why they’ve got thistles on theirs because it’s a Scottish symbol, and there it was in London. Obviously, the team in Java thought that they would get some practice in. I don’t think it was a mistake. I think it was they were just trying it out. (p.c. October 14, 2015)

While the thistle story has several versions, it—more so even than the inclusion of the map and initials—explains how this set of instruments was literally branded as Scottish. From Ritchie’s story, it appears no one explained to the carvers the symbolism of the thistle. One would assume if they understood its importance to Scottish identity, they would not have carved it into a set of instruments intended for England. Ritchie’s tale thus allows him (and by extension Scotland, for whom the thistle was intended) to have a laugh at England’s expense, implying that the thistle will be at home with the Scottish gamelan but will only confuse the English gamelan.

The Name

The gamelan’s name further contributes to its Scottish identity. In Java, gamelans receive individual names, usually given to the largest gong in a naming ceremony. According to Kathryn Duda, “Tradition says the name comes to the name-giver in a dream, and it tends to evoke a geographic element relevant to the gamelan’s home” (Duda 1997). The gamelan instruments intended for Scotland did not receive a Javanese name. According to Joan Suyenaga, Pak Suhirdjan’s widow, Suhirdjan only performed naming ceremonies when specifically requested. She recounted that they never received a request for a naming ceremony from Ritchie or the SCO. These instruments do, however, have a Gaelic name. In May 1991, Eona Craig—who was working with the SCO at the time—drafted a list of five potential names, in English, and asked a Gaelic language specialist for translations of each name. Spioraid an dochais or Spirit of Hope was eventually chosen. Craig explained:

I think it was because [the gamelan] was to be a legacy, a gift to the communities and the schools of the region, and they were looking for something that was about cohesion . . . [;] that’s why they settled on Spirit of Hope. It was something for the future, something that was spiritual, and connected, and using the arts to do that. I think that was the root of it. (p.c. November 13, 2014)

While it is unclear in the end who chose “Spioraid an dochais,” considerable thought went into the naming of Scotland’s first gamelan .12Although anecdotal evidence points to Eona Craig herself, this has not been confirmed. It perhaps did not come to the name-giver in a dream, and one of the other options—Spioraid an iolair-uisge or Spirit of the Soaring Osprey—would have been more indicative of Scotland’s geography. Nevertheless, the Gaelic name of this gamelan encompasses the artistic inspiration of Glasgow’s Year of Culture as well as her plans and promises for the future.

The Sound

One last—and probably mostly serendipitous—Scottish connection lies in the sound of the instruments themselves. While the instruments are in tune with each other, there is no standardized tuning for Javanese gamelan instruments in general. Therefore, no two sets of gamelan instruments sound exactly the same. Gamelan instrument makers are guided by the frameworks of pelog and slendro, but even sets forged by the same maker will sound slightly different. Additionally, pelog and slendro do not adhere to Western tempered tuning.

For Spirit of Hope, some of the slendro and pelog pitches are remarkably close to pitches in Western tempered tuning. See below for the pitches measured in cents of both pelog and slendro sarons from Spirit of Hope:

Pelog saron

Pitch 1 = D5 +19.34 cents13This is based on an average of ten soundings of each pitch using the TonalEnergy Tuner set to equal temperament.

Pitch 2 = Eb5 +48.64 cents

Pitch 3 = F5 +1.56 cents

Pitch 4 = Ab5 -8.85 cents

Pitch 5 = A5 +11.65 cents

Pitch 6 = Bb5 +39.41 cents

Pitch 7 = C6 +9.33 cents

Slendro saron

Pitch 1 = Db4 -33.6 cents

Pitch 2 = Eb5 +16.04 cents

Pitch 3 = F5 +49.01 cents

Pitch 5 = Ab5 -9.5 cents

Pitch 6 = Bb5 +38.98 cents

Pitch 1 = Db5 -21.4 cents

The pelog and slendro scales on Spirit of Hope do not sound particularly Scottish in and of themselves; rather, it is how the instruments are used (i.e., the arrangement of Scottish folk songs and piping tunes) and the fact that these songs are recognizable to Scottish audiences. Naga Mas, the Glaswegian community gamelan group and custodians of Spirit of Hope, have used these sonic qualities to arrange the folk tunes “Ca’ the Yowes” and “Mairi’s Wedding,” as well as the piping tunes “Bonnie Anne” and “Berwick Bully,” for performance on the gamelan. The folk songs were arranged using the gamelan’s pelog tuning. Although this changes the exact pitches, the accommodations to the melody as well as the contour create a recognizable Scottish melody.14I attended a performance by Naga Mas in 2012 at which they played “Ca’ the Yowes” and “Mairi’s Wedding.” Though they took some liberties with the instrumental arrangement of the former, it was immediately recognizable once the singers began. Additionally, after just the first few notes of “Mairi’s Wedding,” the audience audibly reacted, expressing surprise and delight at the familiar song played on unfamiliar instruments. See also Strohschein (2018). When Naga Mas was working with bagpipers, the pipers used electrical tape placed over their chanter holes to effectively tune the pipes to pelog. This has resulted in conflicting attitudes about, but similar reactions to, the sound of this gamelan. Many audience members, workshop participants, and musicians have told me they were drawn to the sound of the gamelan because “it was like nothing I’ve ever heard before.” Yet Mendonça, interviewing workshop participants in Scotland just a few years after Spirit of Hope arrived, observed the following: “[W]hat is the reason stated by a number of clients in Motherwell for liking gamelan? Because it sounds like Scottish Folk Tunes” (Mendonça 1993, 19). To the best of my knowledge, Ritchie did not ask that Spirit of Hope be tuned in any particular way; rather, Pak Suhirdjan tuned these instruments based on his expertise in Javanese gamelan theory as well as his own preferences. The fortuitousness of Spirit of Hope’s sound has, however, allowed for specifically Scottish sonorities to be played, or at least heard, on these instruments.

In her book, Intimate Distance (2012), Michelle Bigenho explores the transplantation of South-American music to Japan and its layers of connection and popularity among Japanese listeners. She considers the “pull of desire toward difference” when encountering the Other (Bigenho 2012, 2). Part of the complexities of attraction, however, lay in the attempt to establish intimacy or familiarity as well. In Bigenho’s research, several Japanese musicians and fans she interviewed described a “common ancestor” that links Japan to South America. Ritchie, Jay, and Glasgow city organizers likewise attempted to achieve both difference and familiarity through their transplantation of Javanese gamelan instruments and by connecting the look, name, and sound of these instruments to Scotland. This created a unique opportunity and a new contextual meaning for members of some of the most precarious populations, namely, adults and children with special needs.

Appropriate Contextual Meaning(s)

In 1991, Glasgow had the reality of Spirit of Hope, a Javanese-made gamelan, and its Javanese-ness was part of the draw. But its physical, semiotic, and sonic Scottish identity was part of an idea of gamelan, one that seems to run counter to MacDonald and Miell’s, Loth’s, and Mendonça’s positions articulated earlier: that “obscurity,” “alienness,” and “strangeness” can result in equality. This desire for or creation of equality is not insignificant, as MacDonald and others have documented how the creation and performance of music allows people with disabilities the opportunity to create identities that separate them—the human being—from their disability.15For further sources on music, disability, and identity, see Meizel (2020), Hirschmann and Linker, eds. (2015), MacDonald, Hargreaves, and Miell, eds. (2002), and Baker (1994). MacDonald and Miell’s study (2002) explains how people with special needs use music as “a powerful tool for helping to extend people’s perceptions of who [they are], playing a central role in [their] life as a means of establishing [their] multifaceted identit[ies,] not only as a person with a particular impairment . . . but also as a musician amongst other things” (MacDonald and Miell 2002, 169). One of the study’s participants explained that after a performance, “it was great that the kids never treated . . . the kids came up and asked for your autograph you know, just the same as an ordinary . . . an ordinary, just the same as they would . . . you know” (MacDonald and Miell 2002, 170; emphasis in original). Another participant described how a woman “started to talk to me normally!” (MacDonald and Miell 2002, 170; emphasis in original) after he expressed his own musical interests and talent. The equality afforded here is not just among special needs participants but also between them and their non-special needs counterparts.

This sentiment was articulated by Ms. Linda Yates, a participant in the 2019 summer Resonate session held at Campbell House on the grounds of Gartnavel Hospital in Glasgow.16Ms. Yates and I learned and played music together during this Resonate session, and she very graciously allowed me to quote her and to use her name. Resonate, a project spearheaded by Good Vibrations17Good Vibrations is a charity based in England that has taken gamelans into prisons to work with inmates to develop creativity, cooperation, and self-actualization. (https://www.good-vibrations.org.uk/) and funded by Creative Scotland,18Creative Scotland is a public organization that supports both tangible and intangible arts in Scotland. They also “distribute funding from the Scottish government and The National Lottery.” (https://www.creativescotland.com/) uses Spirit of Hope for sessions catered for and driven by participants with special needs, although people of all abilities are welcomed. During an exercise in which participants were invited to share their thoughts on what the gamelan session can do/has done, Ms. Yates explained that in the sessions, we all come and work together, even though “we all have different abilities.” Later, during a tea break, Ms. Yates was describing a previous performance in which she had danced. When some people had been incredulous after the show that she had been able to participate, she responded, “Shut up. The wheelchair is invisible. I’m me. I am here.” In this case, the involvement with music and dance facilitated the power of Ms. Yates’s self-assertion.

However, if the point was for Spirit of Hope to be different in order to attract people and to afford equality to participants with special needs, why was so much done to create a Scottish identity for the instruments? And (how) did/does the Scottish identity of Spirit of Hope serve the purposes of the SCO, SRC, SWD, and indeed the participants in projects like Resonate?

The nuance lies in a closer reading of MacDonald’s other contention, that is, gamelan works in Scotland because participants can approach it devoid of stereotypes. MacDonald used this idea in two separate places, in an article he published with Patrick O’Donnell in Occupational Therapy International (MacDonald and O’Donnell 1994), and in a book chapter published with Dorothy Miell in Musical Identities (MacDonald and Miell 2002). In 1994, MacDonald and O’Donnell wrote: “An additional feature of the Gamelan is its relative obscurity in Western culture. This feature allows people to approach the instrument with no preconceived stereotypes” (MacDonald and O’Donnell 1994, 188). In 2002, MacDonald and Miell drew on the same ideas and description when writing that “[Gamelan’s] relative obscurity within Western cultures also makes it an ideal instrument for use with special needs populations as individuals can approach the Gamelan, both as listeners and performers, without any preconceived cultural stereotypes” (MacDonald and Miell 2002, 166; my emphasis).

MacDonald and Miell’s use of “cultural” here is telling. The question becomes why did they add this adjective, and to which culture are they referring? The 1994 article provides a clue in the next sentence: “This aspect appears particularly relevant for people with special needs who may have experienced previous ‘failure’ with music instruction in music groups” (MacDonald and O’Donnell 1994, 188). Here, MacDonald and O’Donnell do not have anything else to add, as that sentence ends the section of the paper, and they go on to describe their methodology. However, because of this contextualization, one possible interpretation is that the stereotypes to which they refer are intra-cultural rather than inter-cultural.19Another possible way to read this is that since people did not have stereotypes about how a gamelan works, it is therefore not limiting for beginners. And indeed, Ian Ritchie and Chris Jay did focus on the fact that gamelan is open, the “perfect mechanism for inclusion” (p.c. Ian Ritchie October 14, 2015) for everyone. But they also did not try to separate that fact from the gamelan’s Javanese origins. They identified these characteristics as Javanese (e.g., group participation, mutual listening, lack of one leader) and used them as reasons for why gamelan would work for people with special needs, whereas other Western ensembles might not. This leads me to believe that the stereotypes mentioned by MacDonald—who worked with the Spirit of Hope instruments for his 1994 article—were not necessarily directed at Javanese, Indonesian, or Southeast Asian cultures. Gamelan works here to dispel the stereotype that people with disabilities cannot play musical instruments. And gamelan helps them overcome the fact that they may have tried and failed to play Western instruments. The Scottish identity of Spirit of Hope allows participants to take ownership of their musical abilities: these instruments may not be Western, but they are, in a way, Scottish. They are obscure and familiar in ways that serve the people who play them.

It is possible to interpret MacDonald and Miell’s use of “cultural” as inter-cultural as well: (1) that Scottish participants would have no preconceived stereotypes regarding Indonesian culture, and (2) that they could use these instruments to create individual identities (like those described by MacDonald and Miell above) and project whatever they wanted onto them and through them. It is also possible that Ritchie and others involved in the initial purchase of Spirit of Hope felt the same. In other words, they recognized the worth and history of Javanese gamelan. But due to its strangeness and alienness, they also imagined that, on some level, the instruments were a blank slate. Or, if not completely blank, “obscure enough” that a Scottish identity could be added to them in ways that capitalize on both familiarity and strangeness. Does this, however, feed or create another stereotype, namely, that exoticism or exoticization is (or can be) unproblematized, a neutral space, if you will, in which aspects of one’s own culture may overwrite some aspects of another. Were Adrian Lee’s criticisms—that the gamelan was not played “as a complete set” (i.e., how it should be played or would be played in Java) and that it was openly accessible without any specific Javanese guidance—directed at cultural appropriation? Is the result, as some current community workers and musicians contend, that gamelan in Glasgow is now perceived only as “special needs instruments”?

Conclusion

The SCO, SRC, and SWD’s ideas of gamelan include making the exotic work practically within the needs of a Scottish community. Programs like Resonate that use Spirit of Hope are continuing, on a more grassroots level, the goals originally imagined at the dawn of Glasgow’s Year of Culture. Spirit of Hope was to be a legacy of this time, and that legacy is one that is expressed in its name, carried in its sound, and carved into its very being. The identity created for these instruments is both Javanese and Scottish, and that imagined identity serves populations with special needs by creating opportunities for agency, self-expression, and allowing them to connect both to their own culture and to another.

This is why understanding musical backstories is so important. Ethnomusicologists (like myself), city organizers (like Chris Jay), classical music organizations (like the SCO and Ian Ritchie), and music therapists/psychologists (like Helen Loth and Raymond MacDonald) often have very different priorities and even different definitions when it comes to explaining our work. Spirit of Hope and its backstory provides an example that highlights these differences but also allows us to bring our own backgrounds and training into dialogue with each other. And the result allows us to better understand how culture, music, and exoticism are used.

It was an idea of what gamelan could be that turned these instruments into a resource that enables musicians and community and social workers to construct, shape, and imagine new meanings within a Scottish context. What Spirit of Hope’s backstory does is give us a scenario in which many of the various uses and angles, the exoticisms and practicalities, of the idea of gamelan may be explored.

Notes

1. This has been debated and indeed, Martopangrawit writes: “In one gembyangan of laras sléndro there are five tones, which can be considered to have equal intervals between them. . . . If we read (sing) the sléndro tones in order, from low to high, or vice versa, and listen to them carefully, we will find both large and small intervals between them” (Martopangrawit 1984, 44).

2. From Richard Pickvance’s A Gamelan Manual 2005.

3. The current Cultural Attaché to the Indonesian Embassy in London, Pak E. Aminudin Aziz, has told me that there are probably 45 current active groups in the UK. This may not count ensembles that are not currently active or those that meet or perform sporadically.

4. Also spelled Seker.

5. I am planning future research that will focus on these other gamelans, particularly the angklung set.

6. Lee’s observations are actually dated May 1990. I believe this was mislabeled as Lee was hired to teach gamelan and lead workshops in Glasgow from March to May 1991. His observations also begin with the phrase, “Since the acquisition of the gamelan,” which took place in December 1990. Because it would have been difficult for him to criticize a gamelan program that was not in place in May 1990, I feel relatively confident he just got the year wrong.

7. In his article, Adrian Lee capitalized the word “Disabled” when referencing people. This is a trend that seeks to empower previously disempowered groups, so I continue it here.

8. See, for example, https://www.wbur.org/artery/2014/07/19/boston-gamelan-music.

9. Lee is, of course, not alone. Within the last few decades, Disability Studies have intersected with musicology and popular music studies to examine music’s use with adults and children with special needs, as well as music’s relation to disability as a social and cultural construction. See, for example, Balensuela 2019, Howe et al. 2016, Williams 2013, Lerner and Straus, eds., 2006, and Lubet 2006.

10. The SCO and the SRC did not necessarily contribute these ideas or this language themselves, but the enticing description of music of the Other, which was intended to arouse curiosity, certainly did not hurt them in terms of encouraging participants.

11. For the purposes of this article, I am choosing to focus on these three components.

12. Although anecdotal evidence points to Eona Craig herself, this has not been confirmed.

13. This is based on an average of ten soundings of each pitch using the TonalEnergy Tuner set to equal temperament.

14. I attended a performance by Naga Mas in 2012 at which they played “Ca’ the Yowes” and “Mairi’s Wedding.” Though they took some liberties with the instrumental arrangement of the former, it was immediately recognizable once the singers began. Additionally, after just the first few notes of “Mairi’s Wedding,” the audience audibly reacted, expressing surprise and delight at the familiar song played on unfamiliar instruments. See also Strohschein (2018).

15. For further sources on music, disability, and identity, see Meizel (2020), Hirschmann and Linker, eds. (2015), MacDonald, Hargreaves, and Miell, eds. (2002), and Baker (1994).

16. Ms. Yates and I learned and played music together during this Resonate session, and she very graciously allowed me to quote her and to use her name.

17. Good Vibrations is a charity based in England that has taken gamelans into prisons to work with inmates to develop creativity, cooperation, and self-actualization. (https://www.good-vibrations.org.uk/)

18. Creative Scotland is a public organization that supports both tangible and intangible arts in Scotland. They also “distribute funding from the Scottish government and The National Lottery.” (https://www.creativescotland.com/)

19. Another possible way to read this is that since people did not have stereotypes about how a gamelan works, it is therefore not limiting for beginners. And indeed, Ian Ritchie and Chris Jay did focus on the fact that gamelan is open, the “perfect mechanism for inclusion” (p.c. Ian Ritchie October 14, 2015) for everyone. But they also did not try to separate that fact from the gamelan’s Javanese origins. They identified these characteristics as Javanese (e.g., group participation, mutual listening, lack of one leader) and used them as reasons for why gamelan would work for people with special needs, whereas other Western ensembles might not. This led me to believe that the stereotypes mentioned by MacDonald—who worked with the Spirit of Hope instruments for his 1994 article—were not necessarily directed at Javanese, Indonesian, or Southeast Asian cultures.

References

Baker, Rob. 1994. The Art of AIDS. New York: Continuum.

Balensuela, C. Matthew, ed. 2019. Norton Guide to Teaching Music History. New York: W. W. Norton and Company.

Bigenho, Michelle. 2012. Intimate Distance: Andean Music in Japan. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Calderwood, Robert. 1988. “The Development of a Policy by the Council for its Continued Involvement in the 1990 European City of Culture and Beyond.” Report by Chief Executive of the European City of Culture Steering Committee.

Conservatory of Music (CoM) UPH. 2016. “Conservatory of Music (CoM) UPH Invited Dr. Helen Loth to Introduce Gamelan as Therapeutic Media.” Accessed April 16, 2018. http://music.uph.edu/component/wmnews/new/4-conservatory-of-music-com-uph-invited-dr-helen-loth-to-introduce-gamelan-as-therapeutic-media.html.

Creative Scotland. 2019. Accessed April 12, 2018. https://www.creativescotland.com/.

Duda, Kathryn. 1997. “The Javanese Gamelan: Ancient Music with Contemporary Appeal.” Accessed April 24, 2018. https://carnegiemuseums.org/magazine-archive/1997/marapr/feat5.htm.

Good Vibrations. 2019. Accessed April 12, 2018. https://www.good-vibrations.org.uk/.

Hirschmann, Nancy and Beth Linker, eds. 2015. Civil Disabilities: Citizenship, Membership, and Belonging. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Howe, Blake, Stephanie Jensen-Moulton, Neil Lerner, and Joseph Straus, eds. 2016. The Oxford Handbook of Music and Disability Studies. New York: Oxford University Press.

Jay, Chris. 1990. Strathclyde Report.

Johnson, Ben. n.d. “The Thistle – National Emblem of Scotland.” Accessed August 30, 2019. https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofScotland/The-Thistle-National-Emblem-of-Scotland/.

Lau, Frederick and Christine Yano, eds. 2018. Making Waves: Traveling Musics in Hawaii, Asia, and the Pacific. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

Lee, Adrian. 1991. “Some critical observations on the project.” Edinburgh: Scottish Chamber Orchestra. [Unpublished item].

Lerner, Neil and Joseph Straus, eds. 2006. Sounding Off: Theorizing Disability in Music. New York: Routledge.

Loth, Helen. 2014. “An Investigation into the Relevance of Gamelan Music to the Practice of Music Therapy.” PhD diss., Anglia Ruskin University.

Lubet, Alex. 2011. Music, Disability, and Society. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

MacDonald, Raymond and Dorothy Miell. 2002. “Music for Individuals with Special Needs: A Catalyst for Developments in Identity, Communication, and Musical Ability.” In Musical Identities, edited by Raymond MacDonald, David Hargreaves, and Dorothy Miell, 163–78. New York: Oxford University Press.

MacDonald, Raymond and Patrick O’Donnell. 1994. “An Investigation into the Effects of Structured Music Workshops with Adults with Mental Handicap.” Occupational Therapy International 1:184–97.

MacDonald, Raymond, David Hargreaves, and Dorothy Miell, eds 2002. Musical Identities. New York: Oxford University Press.

Martopangrawit, Radèn Lurah. 1984. “Catatan-Catatan Pengetahuan Karawitan,” vol. 1. In Karawitan: Source Readings in Javanese Gamelan and Vocal Music, edited by Judith Becker and Alan H. Feinstein, 1:1–121; translated by Martin Hatch, 123–244. Ann Arbor, MI: Center for South and Southeast Asian Studies, University of Michigan.

Meizel, Katherine. 2020. Multivocality. New York: Oxford University Press.

Mendonça, Maria. 1993. “The Javanese Gamelan Comes Home to Scotland.” [Unpublished Manuscript].

_____. 2002. “Javanese Gamelan in Britain: Communitas, Affinity and Other Stories.” PhD diss., Wesleyan University.

Pickvance, Richard. 2005. A Gamelan Manual: A Player’s Guide to the Central Javanese Gamelan. London: Jaman Mas Books.

Proposal for an Indonesian Pilot Study. 1992. “Proposal for an Indonesian Pilot Study in the Creation and Development of a Special Needs Integrated Music Production Company.” Edinburgh: Scottish Chamber Orchestra.

Straus, Joseph. 2011. Extraordinary Measures: Disability in Music. New York: Oxford University Press.

Strohschein, Heather. 2018. “Locating Affinity and Making Meaning: Gamelan(ing) in Scotland and Hawaii.” PhD diss., University of Hawaii at Manoa.

Sumarsam. 2013. Javanese Gamelan and the West. Rochester: University of Rochester Press.

Williams, Jane. 2013. Music and the Social Model. Philadelphia: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.