Abstract

The study of popular music in public education is currently gaining momentum in American schools. Modern Band has been identified as a leading force in this movement, positioning itself as a catalyst for expanding the scope of music offerings in curricula across the US. After considering what guides the Modern Band movement, this article argues that a new direction for it is warranted via the use of songwriting. Using Webster’s four tenets of constructivism (2011), this article offers a conceptual model in support of Modern Band programs where songwriting and learner-constructed experiences are central to its identity. Implications for Modern Band teachers and their students are provided in the article’s conclusion.

Introduction

Popular music education (PME) continues to gain momentum across the contemporary music education world and has been highlighted at international, national, and state conferences (Allsup, 2008; Cremata 2017; Lebler, 2007, 2008; Moir et al., 2019; Rodriguez, 2004). Examples of PME scholarship have also emerged in the literature, with a variety of peer-reviewed journals and books now available (Holley, 2019; Powell et al., 2015; Smith et al., 2017). Recently, the National Association for Music Education (NAfME) began an All-National Honor Ensemble experience for PME, where young musicians perform popular music in rock bands (NAfME All-National Honor Ensembles, 2020). Often deemed a neglected type of music making in formal music teaching, the inclusion of popular music in the classroom has taken decades to reach this point, an achievement that is both notable and significant (Green, 2002, 2008; Woody, 2007).

In certain respects, much of the momentum for PME in the US can be attributed to a non-profit organization called Little Kids Rock (LKR [Little Kids Rock, 2020]). As a catalyst for teaching popular music in secondary education, LKR continues to gain momentum in public schools across the US. LKR seeks to provide music to underprivileged students in schools throughout the country by offering teacher education and instruments to schools where resources for teaching popular music are needed. Its mission is to “transform lives by restoring, expanding, and innovating music education . . .” (Little Kids Rock, 2020). LKR continues to expand its definition of popular music with a renewed recognition and interest in teaching rap, hip-hop, and electronic music.

With the goal of expanding music instruction in public schools across the US, LKR “invented an entirely new kind of school music program” called Modern Band (hereafter MB [What is Modern Band?, 2018]). MB programs include not only teaching students how to play musical instruments often found in popular music but also “to perform, improvise, and compose using the popular styles that they [students] know and love, including rock, pop, reggae, hip-hop, R&B and other modern styles” (What is Modern Band?, 2018). Notable for its continued growth in the field of music teaching and learning, LKR’s MB programs continue to expand in size and are a signifier of PME in the US.

As LKR and its Modern Band programs gain momentum across the music teaching landscape, the methods and approaches teachers use to inform student learning will need continued guidance and support, as research suggests that MB continues to be teacher-directed, an approach that is antithetical to how popular musicians learn and make music (Cremata, 2019b; Green, 2008; Randles, 2018). The purpose of this article, therefore, is to present a model of music instruction for Modern Band that is built on constructivism (Webster, 2011). I use Webster’s four tenets for constructivist learning as well as propose four new attributes for MB, rooted in a learner-led and creative process using songwriting as an instructional tool. When songwriting becomes the central signifier of instruction, I argue that learners use real-world applications in the classroom and apply them to self-directed learning goals. In this modus, students socially engage with one another and learn through a process of trial and error. Implications for the field of music education, MB teachers and programs, and LKR are proposed in this article’s conclusion.

Literature Review: Popular Music Education and Modern Band

The initial movement to include popular music in formalized music education began in Los Angeles during the 1930s, with little impact on actual curricular change across the secondary music education landscape until recently (Krikun, 2017). Nearly 30 years after the initial movement began in the 1930s to include popular music in the curriculum, scholars from all across the country started a variety of projects that attempted to tackle the issue. For example, The Young Composers Project (1959–1962), Yale Seminar (1962), Contemporary Music Project (1963–1973), Manhattanville Music Curriculum Project (1966–1970), Tanglewood Symposium (1967), and Comprehensive Musicianship Project (1965–1971) were organized to refocus school music programs in ways that diversified music making and included popular music (Choate et al., 1967; Washburn, 1960; Werner, 1979). A similar theme across each of these conferences was a recognition that the types of music and instruments taught in American music education were limited to a singular (monolinguistic) form of music making. Participants discussed the importance of diversifying the types of instruments taught at the secondary level, the methods and approaches that might increase creative thinking, and instruction that supported learner-led facilitation (Washburn, 1960; Werner, 1979).

Although minimal change has been made regarding the inclusion of popular music in public music education since these deliberations, a variety of publications related to PME has become increasingly available (Holley, 2019; Powell et al., 2015; Smith et al., 2017). They offer different perspectives about teaching popular music, including advocating for, coaching of students in, and approaches to facilitating a popular music program (Moir et al., 2019). Frith (1978, 1981, 1988, 1998, 2002) wrote extensively on PME and advocated for the inclusion of rock music, suggesting that it offers an avenue for broadening musicianship and increases music participation in educational settings. Others, such as Gardner (2010), wrote about similar positive outcomes. Emmons (2004), Green (2002, 2008), Jaffurs (2004), Kladder (2017), Kratus (2007), Lebler (2007), Randles (2009, 2014), Vasil (2015), and Woody (2007) all argue that music instruction would benefit by including popular music in the classroom, thereby increasing participation, supporting musical creativity, and offering social-collaborative, self-directed, exploratory, and learner-centered approaches to music making. Perhaps one of the most extensive contributions about coaching a popular music ensemble is in Holley (2019). Finally, each of these authors argues for an approach to PME that is learner-led, not teacher-directed.

To further this notion, some of the most significant contributions to PME research and pedagogy are attributed to the work of Green (2002, 2008), who argued that learning and performing popular music is inherently a creative experience, where popular musicians produce original material on their chosen instruments. Griffith (2012) supported these claims and wrote that PME provides the ideal space for students to compose, improvise, and develop their musicianship through original and authentic avenues of expression in classrooms that are appropriately facilitated. As Green (2002) has maintained, popular musicians learn music through a process of trial and error, where they acquire musical skills by covering pre-existing material or writing original songs. This process supports their ability to learn the necessary skills on instruments as needed, while working informally in ways that are self-directed. Green (2002, 2008) has also found that creativity was naturally embedded into the process of learning popular music for informally trained musicians, which is likewise supported in some of the most notable contributions toward understanding creativity in music teaching and learning (Burnard, 2012). For example, Burnard outlines the specific places in which creativity is able to flourish within the popular music landscape and maintained that popular music classrooms could provide ideal places for developing new approaches for instruction that support creativity and songwriting.

As authentic PME relies on learner-led and self-directed approaches in the music classroom, calls to encourage learner-led facilitation through a constructivist epistemology have permeated much of the music education pedagogical literature (Cremata, 2017; Webster, 2011; Williams & Kladder, 2019). Additionally, creative activities, including songwriting, have also been recognized as an important component of student learning, though lacking in many music classrooms across the US (Kratus, 2016; Williams, 2011). It has been argued that teachers often focus on teacher-directed approaches that are antithetical to a classroom that supports creativity, including MB classrooms (Randles, 2018; Webster 2011).

The MB movement in American schools is a relatively new phenomenon. According to Powell and Burstein (2017), it is “a stream of music education that has two simple guiding attributes: repertoire and instrumentation. The repertoire is what might typically be thought of as popular music to mean of the people[,] … [whereas Modern Band] encompasses broad genres of music and more narrow genres” (p. 245). MB programs were initially designed to assist in addressing the disconnect between what music students experience outside formal school learning and those inside the school (Rodriguez, 2004). The MB curriculum is built on new kinds of school music, where students perform popular music they “know and love, including rock, pop, reggae, hip-hop, R&B, and other modern styles” (Little Kids Rock, 2019). Although the two guiding attributes for the MB program are notable and warranted, a continued examination of the types of instructional practices and creative availabilities within the MB curriculum and training may shape and guide the direction of its teacher education.

In support of this critique, Byo (2018), Randles (2018), and Weiss et al. (2017) found two areas that warrant further investigation: (1) the pedagogy found in MB classrooms may not support learner-constructed experiences as originally intended; and (2) the types of creative activities, such as songwriting, composition, and improvisation, may be limited. Randles (2018) found that songwriting constituted less than 32 percent of the overall learning experience in the MB classrooms surveyed. The same percentage of MB teachers also included improvisation on popular music instruments (32 percent). Referred to by Randles as “nominal” and indicative of a “minority of teachers” (p. 223), these results contrast strongly with what Powell and Burstein (2017) identify as two key attributes that are central to MB programs in the US. Randles also found that students in MB programs continue to perform few songs of their choice (66 percent), have not composed an original song (68 percent), and do not improvise (68 percent).

This process poses a challenge for MB programs because many teachers who adopt an MB curriculum will rely on previous teaching methods and implement teacher-directed, linear-oriented, and method-driven instruction (Cremata, 2019a, 2019b). This is supported by research on MB programs, as Randles (2018) found that many MB teachers focus on covering and performing pre-existing materials, delivered in a format that was teacher-directed.

These data are in conflict, however, with how popular musicians learn, perform, and make music and pose instructional challenges for PME and MB teachers in the US (Green, 2002; McIntyre, 2008, 2016). Research suggests that although popular musicians cover and emulate pre-existing songs in studios and in live performances, they spend considerable time exploring ideas in recording studios and writing original material (Bennett, 2011; Toynbee, 2016). To offer an authentic approach to PME, MB programs could emulate similar experiences, which are built on constructivist and learner-led attributes, where learning is self-directed, based on trial-and-error, collaborative, and meaningful. In this modus, creating music would be central to the learning process and support opportunities for students to explore and connect their songs to lived experiences outside the classroom. This central argument is further supported in the research of Byo (2018), who found that MB classrooms were often teacher-directed, and more time was warranted for “mucking around” (p. 266). Constructivist approaches to music learning may offer one way in guiding a new model for music instruction for MB, with songwriting at the core of the learning process.

Constructivism in Music Learning

According to Webster (2011), constructivism is a process where: “(1) knowledge is formed as part of the learner’s active interaction with the world; (2) knowledge exists less as abstract entities outside the learner and absorbed by the learner; rather, it is constructed anew through action; (3) meaning is constructed with this knowledge; and (4) learning is, in large part, a social activity” (p. 36). These four tenets are built upon previous investigations into constructivism, where theorists and researchers have identified that a constructivist “view of learning suggests an approach to teaching that gives learners the opportunity for concrete, contextually meaningful experience(s) through which they can search for patterns, raise their own questions, and construct their own models, concepts, and strategies” (Fosnot & Perry, 1996, p. 9).

When applied to music learning, Webster (2011) wrote, “the mere mastery of facts is not enough and [that] real understanding is evidenced by forms of application . . . [coming] from active engagement in the highest quality of music experience possible” (p. 35). With this understanding, the formation of authentic knowledge begins with active engagement in the music-making experience. These experiences are not entirely driven by the teacher and, ideally, would allow students the opportunity to not only “know about, but know within” (Webster, 2011, p. 35). In this modus, the learner is able to construct a new understanding from something they already know. This process of learning shares attributes with learner-led instruction, whereby the learner is not assumed to know little or nothing. Rather, learning is individualized and is supported by a tailored approach for each musician that is highly involved and active (Williams & Kladder, 2019).

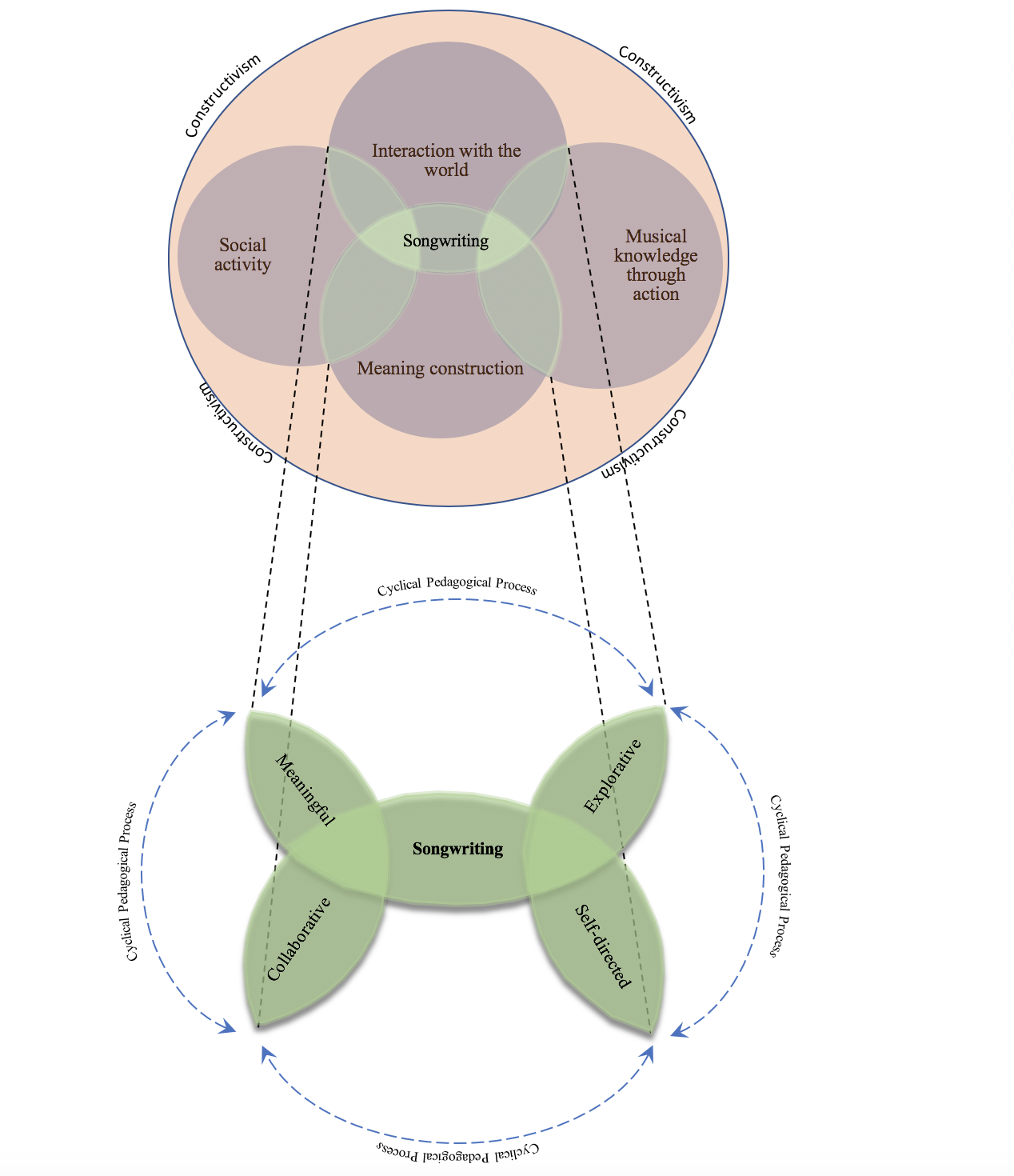

This aligns with Hoover (1996), who explained that there is no tabula rasa upon which new knowledge is drawn. In the music classroom, this likely means that there is no method or textbook driving the learning process; rather, a process that requires all students to follow a linear and product-driven approach is advanced. Linear and product-driven types of instruction assume that all students learn the same way in this approach and marginalize learners who fall outside the conventional box for learning. Conversely, a teacher who implements a constructivist approach recognizes and validates a student’s previous music experiences, reassures them there is value in these experiences, and enriches the learning process with their prior musical knowledge. In turn, the teacher then provides relevancy to their personal learning interests (Figure 1). This “interaction with the world” and “richness of previous experience” allow students to construct a learning outcome, or set of learning outcomes, that best fit their needs and learning goals, which is an ever-evolving process.

Figure 1. Learning is connected with previous music experiences and interactive with the world

Webster (2011) maintains that the most significant and meaningful way for learners to gain new knowledge is through action, whereby new knowledge is being built upon a “reality [that is] based on experiences and interactions with the environment” (p. 38). He goes on to state that this guiding principle is different from what is common for most music teaching and learning practices in contemporary education, and that most instruction relies on teachers making the musical decisions, doing most of the work, and controlling most aspects of classroom learning. In many ways, these characteristics have become central identifiers of education today (Robinson & Lee, 2011).

On the other hand, a constructivist approach to music learning would allow the teacher not only to gain a deep appreciation and understanding of each individual learner in the classroom but also develop a plan of action for learning that is co-created with the student(s). In this modus, students take action to find the answers they need to solve the problem. These actions require students to interact with their surroundings in ways that many classrooms do not, whether at home or at school, and in ways that create a richness of experiences. Musical knowledge is therefore gained when students take the driver’s seat and actively engage in their own knowledge formation (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Students develop new musical knowledge through action

For Webster (2011), music teaching and learning often focuses on the objective reality, where teachers form a “kind of mirror of reality . . . that . . . can be studied” (p. 38). When teachers create a reality that is studied by students, the meaning is created by the teacher alone and thus a gap of meaningful experiences is created between the content and student, resulting in disengaged students and classroom management issues. However, if students are able to co-create a reality with their teachers and peers, in ways that are learner-led, self-directed, and co-created, the ownership shifts to the student, not the teacher (Figure 3). This allows students to

Figure 3. Creating meaning in the music classroom is central to a constructivist approach

apply their cultural and personal understandings to classroom learning, a defining characteristic of a constructivist approach. This is especially important in a contemporary culture, where music teaching and learning in the US has been challenged to address the widening gap between the experiences of music students, whether outside or inside school (Jaffurs, 2004).

The final tenet of Webster’s application of constructivism to the music classroom (2011) suggests that the “issues of social interaction must be central” (p. 38) to the learning experience where “knowledge is sustained by social processes” (p. 39). Other scholars in music education have identified the significance of social learning as well (Bennett, 2011, 2012; Braheny, 2006; Gooderson & Henley, 2017; Kratus, 2016; Marade et. al., 2007; Williams & Williams, 2016). Significantly, research suggests that a substantial portion of the world’s popular music relies on collaboration for its success and would be a signifier of music instruction when embedded into a constructivist approach to learning (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Social collaboration as the final tenant of Constructivism

In this approach, an MB classroom would be social and collaborative (Green, 2008). This is also supported by Byo (2018), who after researching an MB program found minimal amounts of social collaboration in the classroom: “Might there be benefit in structuring more experiences in MB . . . to include permissible ‘mucking around’? The teacher observes, then guides or demonstrates after students have attempted to problem-solve on their own” (p. 266). As students “muck around” in social groups, they “figure out” what “works” or “doesn’t work.” Ideally, this approach would be in accord with how popular musicians learn (Bennett, 2011; Braheny, 2006; McIntyre, 2008; West, 2016; Williams & Williams, 2016). The strengths and weaknesses of each student might even be used to help them support each other. With proper facilitation and guidance, this would likely encourage students to develop an increased interest in music that may contribute to life-long music participation (Davis, 2005; Draves, 2008).

In the MB classroom, social collaboration may take on a variety of different forms. For example, one student may have more interest in writing lyrics, while another may be curious about writing chord arrangements or guitar riffs. Collaborations of this sort would support opportunities for immediate feedback and collaborative learning (Bennett, 2011; Braheny, 2006). An MB classroom that supports social collaboration through a process of songwriting might include conflict resolution where: (1) the lyrics or music may be written separately for particular sections and brought together later; (2) appropriate collaboration exercises may be implemented; or (3) students may brainstorm in small groups on themes or topics and share ideas. In sum, social collaboration is a central signifier of constructivist learning and would support the creative process, encourage ideation, peer-to-peer evaluation, and peer-to-peer feedback (Bennet, 2011; McIntyre, 2019; West, 2016; Williams & Williams, 2016).

Discussion: Applying Constructivism as a Pedagogical Approach for Songwriting in Modern Band

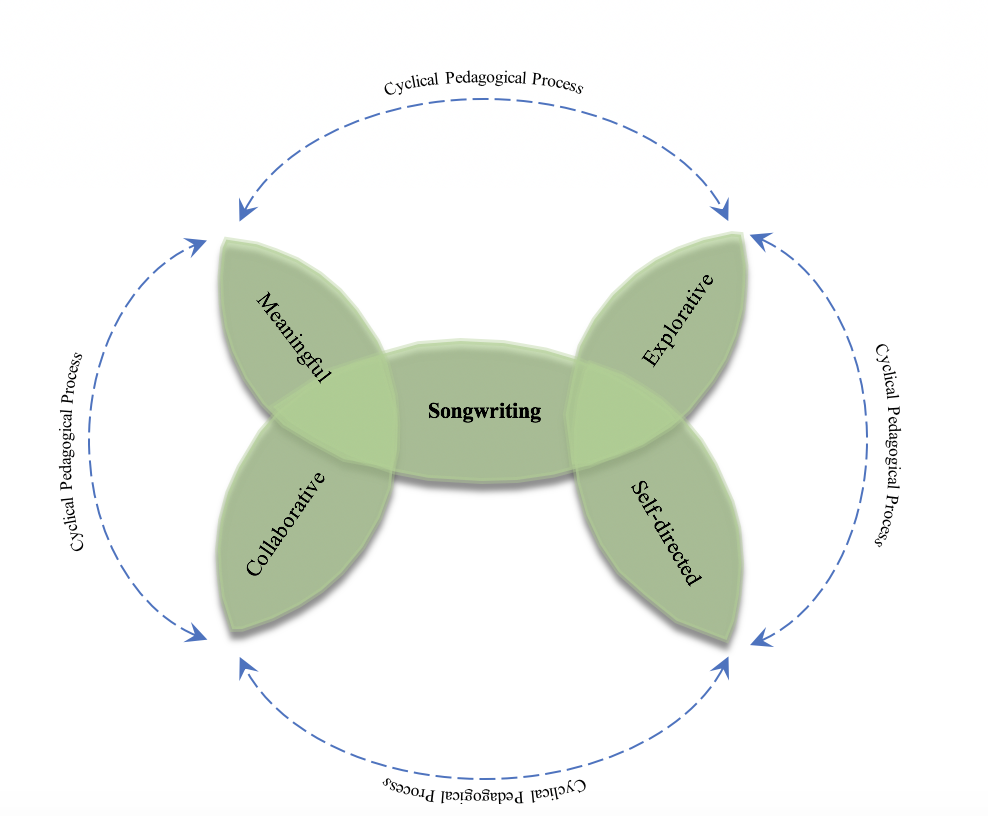

If Webster’s (2011) four tenets of constructivism are applied to a new pedagogical approach for music instruction in an MB songwriting class, a classroom that is explorative, self-directed, collaborative, and meaningful emerges. Each of these attributes supports a constructivist approach to learning, where students make most, if not all, of the musical decisions and are guided through a creative process that is self-directed and explorative (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Four new guiding attributes for Modern Band based in songwriting

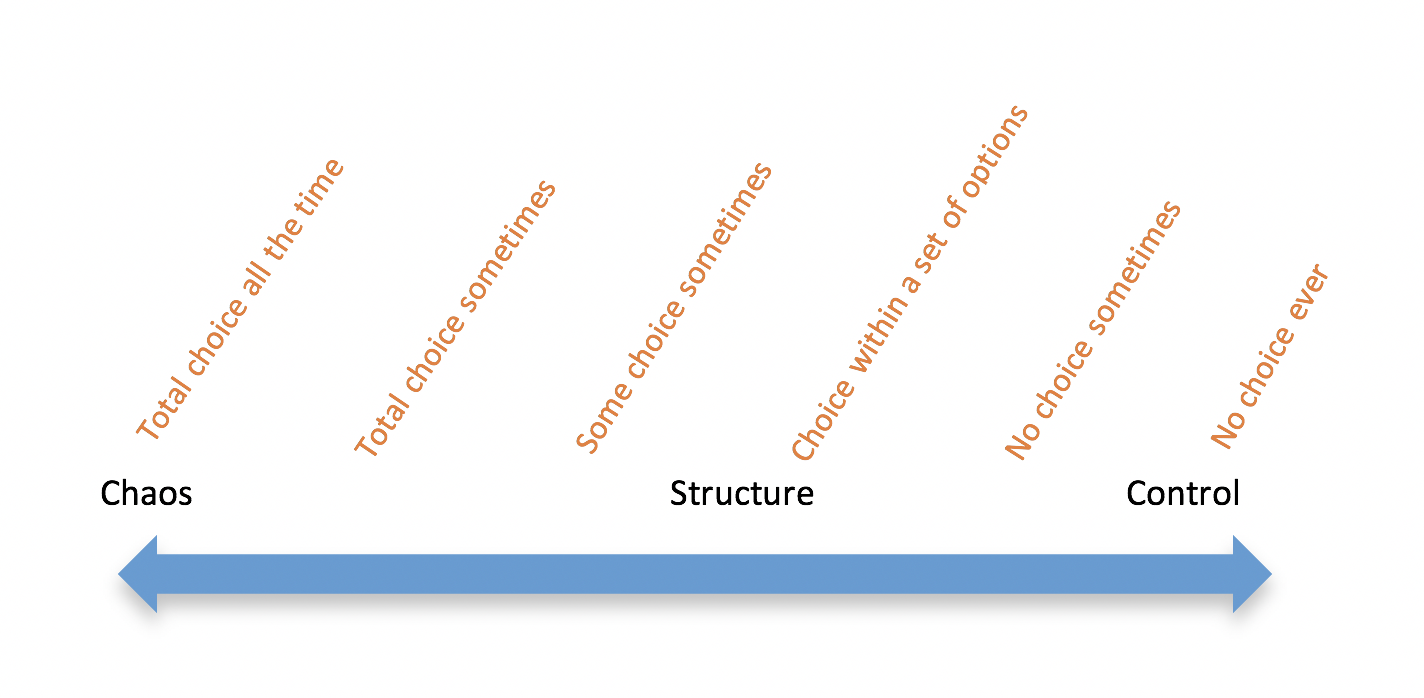

One of the most significant indicators of a constructivist MB songwriting class is found in the role of the teacher. It would require a shift in pedagogy, where the teacher would allow space for students to construct new knowledge. It may require the teacher to adopt a mentor/mentee, or “guide on the side,” approach (Cremata, 2017, p. 64; Williams & Kladder, 2019). As a facilitator and co-musician, the teacher would work with student songwriters to “help the student realize and refine his or her own musical ideas, not the teacher’s musical ideas” (Kratus, 2016, p. 63). It would necessitate a shift of control away from the teacher and toward the student. A flexible classroom space, where student learning would be moderated and guided along a continuum of learning, is indicated in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Constructivist teaching on a continuum of learner-led experiences (from The Learner-Centered Music Classroom: Models and Possibilities [Williams & Kladder, 2019])

A shift toward a learner-led pedagogical approach would likely require a mix of total choice sometimes or choice within a set of options. Rarely would a constructivist classroom permanently exist in total choice or no choice whatsoever. An MB songwriting class based on this approach is also validated and supported by research, as scholars have identified that ideal music learning experiences build upon action, involvement, and learner-constructed knowledge, where students often learn by trial-and-error and explore ideas in open and collaborative learning spaces (Barrett & Webster, 2014; Randles, 2012; Webster, 2011; Williams, 2014, 2015; Williams & Kladder, 2019).

As the proposed approach suggests, students would spend considerable amounts of time exploring musical ideas and sounds in self-directed and/or collaborative spaces. This process would repeat numerous times through a single class and require consistent refinement of their musical ideas, moderated by the teacher (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Cyclical pedagogical process for an MB songwriting class

Therefore, new knowledge would be formed through a process of exploration and trial-and-error, one that has been deemed as genuine and authentic to how popular musicians learn (Bennett, 2011, 2012; Green, 2002; McIntyre, 2008, 2016; Toynbee, 2016). In this modus, classroom learning would focus more on the creative process of making music and less on covering existing material or learning a predetermined set of skills determined necessary for a musical performance (Randles, 2018). It would require a refocus or reimagination of the instruction commonplace in many music classrooms, including MB classrooms, and redefine music instruction (Cremata, 2017, 2019a, 2019b). Learners would be more active in the decision-making process, choose the musical material they desired to learn, find the appropriate materials for accomplishing the set tasks they have chosen, and teachers, who would act more like coaches, would facilitate or guide their processes (Holley, 2019).

With songwriting as the locus of the learning experience in the MB classroom, students could ideally interact with their world as they create original material. This may include writing lyrics in reaction to current global or national events, personal life experiences, or other learner-chosen material (Kratus, 2016; Tobias, 2013). Students might also explore rhyme and meter in lyric writing, or search for relevant videos or other material needed to accomplish their songwriting tasks. All of these experiences share a closeness as to how most popular musicians learn, experience, or perform music, and align with Webster’s approach (2011) to constructivism in music learning (Green, 2002; Jaffurs, 2004).

Such classroom social learning activities not only may seem strikingly new for some teachers but also may require a new paradigm of music instruction. For example, Byo (2018) wrote that facilitated social learning may sometimes be confused with poor classroom management, but it is in fact conducive to meaningful music learning. Quoting Green (2006, 108), Byo writes:

There is “mucking around. It sounds like chaos. Someone is playing something on the piano [that has] nothing to do with the chosen song. . . . There is random drumming and talking” (p. 108). . . .Viewed from Green’s perspective, the talking and noodling are not about mismanagement; they are about natural learning, an inevitable phase of informal learning in popular music performance. (2018, p. 266)

If songwriting became the central identifier in an MB classroom, music learning would align well with Webster’s epistemology of knowledge formation. As students explore and create new musical ideas, they might challenge facts, find new knowledge, or challenge existing knowledge in ways not previously considered (Bishop, 2019; Gooderson & Henley, 2017; Hughes & Keith, 2019; Sternberg, 1999; West, 2016). Learning might appear haphazard, messy, or chaotic, but it would lead to somewhere meaningful, if guided and facilitated properly. It may likewise offer a new avenue for students to express their life experiences in ways not possible via other subjects in school (Hughes & Keith, 2019). This is significant, because scholars have argued that songwriting offers students the opportunity to cope with and manage social and psychological difficulties, including emotional stability, self-expression, and self-discovery (North et al., 2000; Riley, 2012; Saarikallio & Jaakko, 2007).

Songwriting requires students to engage with music in ways that are more creative than working with pre-existing materials (McIntyre, 2016). For example, learners would be challenged to engage in problem-solving techniques, resulting in a music that would be authentic and meaningful because it is the music they created (McIntyre, 2016; Wiggins et al., 2005). This aligns with what Hoover (1996) explained as central to an engaging musical learning experience, where the learner is active throughout the songwriting process and able to interpret their understanding of the material in relevant ways.

The constructivist approach to learning suggests that when learners engage in the songwriting process, they interact, explore, and discover information (both musical and non-musical) within their world that assists them in achieving their musical goals. This process would require that learners think critically about this material and make decisions about how it may or may not fit into their songs. This type of music learning aligns with a process similar to problem-solving in creativity research (Csikszentmihalyi, 2014). Such idea finding could lead, however, to a few dead ends, that is, an action in learning that may be ambiguous, elusive, and thus require direction (Gooderson & Henley, 2017; McIntyre, 2008, 2016; Toynbee, 2016; West, 2016).

A concrete example of this type of music learning might include lyric writing. As students write lyrics for their songs, they construct a musical representation of their interests and experiences (Reinhart, 2019; Pattison, 2011). The writing of lyrics might take many forms, such as: (1) rhyme (and types of rhyme), (2) critical evaluation of the simplicity of the lyric content, (3) narration of the titles, (4) the attitude or message of the song to be portrayed, (5) prosody and meter, and (6) lyric context (Gooderson & Henley, 2017; Pattison, 2011; Reinhert, 2019). Knowledge about lyric writing might be gained from a variety of places, including: (1) news and media on either the radio, TV, phones, or tablets; (2) Spotify or Amazon Prime; (3) social media (i.e., Facebook or Twitter); (4) poetry; (5) conversations with teachers, friends, or acquaintances; and (6) life experiences that students bring to class.

A central feature of the proposed constructivist approach suggests that the four attributes are cyclical and not linear. There is no specific goal with respect to the learning process in an MB songwriting class, although a song may reach a “final” form in which students continue to edit, change, or add to their work for as long as they choose. The approach in question suggests that each of the four attributes continues and involves a repeated process, where the student continues to explore new musical or non-musical ideas, direct themselves to find answers to the problems that arise when learning, construct new meaning as they learn, collaborate with one another to find answers and share ideas, and gain new knowledge as they interact with the world. Meaning is therefore created through the entirety of the songwriting process and is owned by the student(s).

Conclusion and Implications

MB and its inclusion in public schools continues to hold promise for music students as a form of music making that supports PME in the US. However, as MB programs continue to expand and more teachers adopt PME programs in their schools, continued study of the methods and approaches teachers use is warranted. The proposed approach for MB in this article is intended to assist MB teachers and the types of teacher education programs that embrace MB. It challenges existing MB teachers to increase constructivist approaches to music learning, so that songwriting is central to the music-making process in popular music education, a process that is authentic to how popular musicians learn (Green, 2002, 2008). The approach I propose suggests moving away from method-driven instruction that is teacher-directed and toward a learner-constructed and creative music-making experience (Cremata, 2019a).

MB programs offer exciting musical experiences for students, and when situated within a philosophical, sociological, and epistemological approach that is constructivist in design, offer opportunities for meaningful music learning. I posit that if songwriting became a central identifier of the music-making process in all MB programs, both learners and teachers could co-create music in spaces that support the construction of new knowledge. Learning would become explorative, collaborative, meaningful, and self-directed. This supports what Bowman (2004) states as important for music learning, arguing that it should include a “breadth of intended appeal, mass mediation and commodity, amateur engagement, continuity with everyday concerns, informality, here and now pragmatic use . . . , appeal to embodied experience, and emphasis upon process” (2004, 36–37). When applied to MB, this suggests a “messiness” associated with the learning process, where the focus is less on product and method and more on what is constructed by and for the learner.

As the K-12 music learning community expands its understanding of ways to create diverse, inclusive, and well-rounded music education experiences for all, the inclusion of MB in the US will continue to gain momentum across the music teaching landscape. With this fact as a guiding principle, assuring that current practicing teachers and those interested in starting MB programs are educated on how popular musicians learn is of vital importance. Continued conferences related to PME research at all levels are warranted and additional research investigating the songwriting process of popular musicians is also needed. This data will help to further the mission and goals of PME and MB in ways that are genuine and authentic for all students.

There are implications in relation to MB for those in higher education as well. University faculty who continue to learn and teach MB at their institutions need to expand its scope. These faculty are often linked with undergraduate and graduate music teacher education programs that include a curriculum which often neglects songwriting and popular music, a state of affairs that has been recognized by music education scholars, such as Cremata (2017), Kaschub and Smith (2014), Kladder (2017, 2019), Kratus (2016), Powell and Burstein (2017), and Williams (2015). To further change in undergraduate and graduate programs across the US, faculty might:

(1) Offer songwriting classes in popular music.

(2) Require classes on improvisation and learning how to play popular music instruments.

(3) Create spaces for students to collaborate in rock/pop band ensemble settings.

(4) Diversify the types of instruments and musicianship accepted in music education programs.

(5) Involve more students in the creative process of making music.

(6) Focus less on reading music from notation and increase education in popular music.

(7) Model and teach the value of learner-led and non-linear music learning approaches, similar to those suggested in this article.

To advance this notion, in 2014 the College Music Society released a report suggesting the need to both increase creativity and diversify the types of musicianship experiences in conservatory-style schools of music in the US. Other scholars have also raised awareness of these issues, calling for curricular change so that undergraduate music education programs embrace broader approaches to music making (Caswell & Smith, 2000; Cremata, 2017; Ezquerra, 2014; Finney, 2016; Folkestad, 2005, 2006; Karlsen & Vakäva, 2012; Randles, 2012; Williams, 2014, 2015). Advancing the aforementioned suggestions will support my proposed model even further, where prospective music teachers might learn popular music in social spaces that focus on creative thinking and learner-constructed knowledge and, hopefully, implement similar experiences for students in their future classrooms.

Webster’s four tenets of constructivism (2011) offer guidance for MB teachers to reexamine their pedagogical choices in the classroom. They are also valuable as a means to shape the future direction of MB programs in the US. The approach in this article recognizes the value and importance of constructivist approaches to learning that are based on creative music-making processes and applied to PME in MB programs across the US. As MB continues to be used as a catalyst for change in music teaching and learning, its teachers could emerge as leaders in constructivist music-learning experiences. To conclude this article, I propose the following considerations and curricular examples for MB teachers that support a constructivist classroom (adapted from Webster, 2011):

(1) Musical meaning is more effectively constructed when the learner directs it

Curricular example: Allow students opportunities to create their own learning goals for the songwriting class. Record each learning goal separately and create weekly check-ins regarding their progress. Ask students to record their process, i.e., what resources are they using to accomplish their goals? Where are they finding their resources? How much progress did they make this week? Have students reflect and record their answers in a journal; this will offer one approach to monitoring student progress. Regularly assess how much control you are assuming in the classroom and decide whether it is mostly you or the students.

(2) Social-collaborative learning allows students the opportunity to teach one another in the songwriting process

Curricular example: Allow students opportunities to work in peer-led groups that are facilitated or coached by the teacher. Encourage students to take on a variety of roles. For example, who will write the lyrics? Who will figure out the musical parts? Is there a designated leader in the group? How do you assure that everyone is engaged in the process? Create student-led accountability and have students write in their journals on what is happening socially in the group.

(3) Respecting the previous music experiences that students bring into the classroom offers personal ownership over the music-making experience

Curricular example: Start by asking yourself: What do you know about the musical interests of each student in your classroom? You might try creating a Google survey, where you ask students to describe their musical knowledge and interests. What instruments do they play? What instruments do they want to play? What types of music do they listen to? Do they take lessons on an instrument? This type of information is important in establishing individual learning goals for your classroom. Avoid showing bias toward a particular style of music your students are interested in; instead, help them to respect all music, and model respect for all music from your perspective. Try creating a song list for each group that reflects the types of music they enjoy listening to, along with one of your own as a teacher.

(4) Constructivist approaches to music instruction allow space for students to learn through exploration and music making

Curricular Example: How much emphasis is placed on finding the right answer immediately vs. allowing time for exploration and trying things out? This may require the teacher to take a step back and not give students an immediate answer. Reflect daily on your coaching. How many answers did you provide for your students vs. lead them in the right direction? This can be hard and challenging for some students, but it is vital to provide space for them to work toward their goal.

(5) Constructivism focuses more on the product than the process

Curricular example: How much of the songwriting class is focused on a final performance over the process of writing the music? Allow students the opportunity to make the decision on how they would like to share their song with the class. Is it a recording? A multitrack performance? A video? A live performance? Explore the variety of options and avoid placing pressure to have each student/group perform the same way.

(6) Creative exploration and songwriting require flexibility and adaptiveness

Curricular example: Allow time and space for students to explore sounds, lyrics, current global events, and material relevant to them. Being flexible means learning what they are into and being adaptable means that you can work with them as things change. Consider shifting a learning goal when/where needed. Recognize that songwriting is a creative process and sometimes that creative moment will come at different times. A student may decide they want to learn a different instrument in the unit. This is an opportune moment to reflect and propose a solution that is agreeable to your student (i.e., maybe there is no need to immediately say no).

References

Allsup, R. E. (2008). Creating an educational framework for popular music in public schools: Anticipating the second-wave. Visions of Research in Music Education, 12(1), 1–12.

Barrett, J. R., & Webster, P. R. (Eds.). (2014). The musical experience: Rethinking music teaching and learning. Oxford University Press.

Bennett, J. (2011). Collaborative songwriting – The ontology of negotiated creativity in popular music studio practice. Journal on the Art of Record Production (5).

Bennett, J. (2012). Constraint, collaboration and creativity in popular songwriting teams. In D. Collins (Ed.), The act of musical composition: Studies in the creative process (pp.139–169), Ashgate.

Bennett, J. (2018). Songwriting, digital audio workstations, and the Internet. In N. Donin (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of the creative process in music. Oxford.

Bishop, D. (2019). The benefits of prosody for music educators and students: Unpacking prosody and songwriting strategies in the classroom. Journal of Popular Music Education, 3(1), 113–128.

Bowman, W. (2004). Pop goes…? Taking popular music seriously. In C. X. Rodriguez (Ed.), Bridging the gap: Popular music and music education (pp. 29–49). MENC.

Braheny, J. (2006). The craft & business of songwriting (3rd ed.). Writer's Digest Books.

Burnard, P. (2012). Musical creativities in practice. Oxford University Press.

Byo, J. L. (2018). “Modern Band” as school music: A case study. International Journal of Music Education, 36(2), 259–269.

Caswell, A. B., & Christopher Smith. (2000). Into the ivory tower: Vernacular music and the American academy. Contemporary Music Review, 19(1), 89–111.

Choate, R. A., Fowler, C. B., Brown, C. E., & Wersen, L. G. (1967), The Tanglewood symposium: Music in American society. Music Educators Journal, 54(3), 49–80.

Cremata, R. (2017). Facilitation in popular music education. Journal of Popular Music Education, 1(1), 63–82.

Cremata, R. (2019a). The Schoolification of popular music. College Music Symposium, 59(1), 1–3.

Cremata, R. (2019b). Popular music: Benefits and challenges of Schoolification. In Z. Moir, B. Powell, & G. Dylan Smith (Eds.), The Bloomsbury Handbook of Popular Music Education: Perspectives and Practices (p. 415). Bloomsbury Academic.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2014). Society, culture, and person: A systems view of creativity. In The systems model of creativity: The collected works of Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (pp. 47–61). Springer Netherlands.

Davis, S. G. (2005). “That thing you do!”: Compositional processes of a rock band. International Journal of Education & the Arts, 6(16), 1–19.

Draves, T. J. (2008). Music achievement, self-esteem, and aptitude in a college songwriting class. Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education 178, 35–46.

Emmons, S. E. (2004). Preparing teachers for popular music processes and practices. In C. X. Rodriguez (Ed.), Bridging the gap: Popular music and music education (pp. 159–174), MENC.

Ezquerra, V. (2014). I did that wrong and it sounded good: An ethnographic study of vernacular music making in higher education [Doctoral dissertation, University of South Florida]. Scholar Commons. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/5012.

Finney, J. (2016). Music education in England, 1950–2010: The child-centred progressive tradition. Routledge.

Folkestad, G. (2005). The local and the global in musical learning: Considering the interaction between formal and informal settings. In P. S. Campbell (Ed.), Cultural diversity in music education (pp. 23–27). Australian Academic Press.

Folkestad, G. (2006). Formal and informal learning situations or practices vs formal and informal ways of learning. British Journal of Music Education, 23(2), 135–145.

Fosnot, C. T., & Perry, R. S. (1996). Constructivism: A psychological theory of learning. In C. T. Fosnot (Ed.), Constructivism: Theory, perspectives, and practice (pp. 8–33). Teachers College, Columbia University.

Frith, S. (1978). Sociology of rock. London: Constable.

Frith, S. (1981). ‘The magic that can set you free’: The ideology of folk and the myth of the rock community. Popular Music, 1, 159–168.

Frith, S. (1988). Copyright and the music business. Popular Music, 7(1), 57–75.

Frith, S. (1998). Performing rites: On the value of popular music. Harvard University Press.

Frith, S. (2002). Look! Hear! The uneasy relationship of music and television. Popular Music, 21 (3), 277–290.

Gardner, R. (2010). Rock ‘n’ roll high school: A genre comes of age in the curriculum. In A. Clements (Ed.), Alternative approaches in music education: Case studies from the field (pp. 83–95). R&L Education.

Gooderson, M., & Henley, J. (2017). Professional songwriting: Creativity, the creative process, and tensions between higher education songwriting and industry practice in the UK. In G. D. Smith, Z. Moir, M. Brennan, S. Rambarran, & P. Kirkman (Eds.), The Routledge research companion to popular music education (pp. 257–271). Routledge.

Green, L. (2002). How popular musicians learn: A way ahead for music education. Routledge.

Green, L. (2006). Popular music education in and for itself, and for “other” music: Current research in the classroom. International Journal of Music Education, 24, 101–118.

Green, L. (2008). Music, informal learning and the school: A new classroom pedagogy. Routledge.

Griffith, J. J. (2012), Students sing the blues: How songwriting inspires authentic expression. Language Arts Journal of Michigan, 28(1), 46–51.

Holley, S. (2019). Coaching a popular music ensemble: Blending formal, non-formal, and informal approaches in the rehearsal. McLemore Ave Music.

Hoover, W. A. (1996). The practice implications of constructivism. SEDL Letter, 9(3). https://sedl.org/pubs/sedletter/v09n03/practice.html.

Hughes, D., & Keith, S. (2019). Aspirations, considerations and processes: Songwriting in and for music education. Journal of Popular Music Education, 3(1), 87–103.

Isherwood, M. (2014). Sounding out songwriting: An investigation into the teaching and assessment of songwriting in higher education. The Higher Education Academy, York, England.

Jaffurs, S. E. (2004). The impact of informal music learning practices in the classroom, or how I learned how to teach from a garage band. International Journal of Music Education, 22 (3), 189–200.

Karlsen, S., & Väkevä, L. (Eds.). (2012). Future prospects for music education: Corroborating informal learning pedagogy. Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Kaschub, M., & Smith, J. (Eds.). (2014). Promising practices in 21st[-]century music teacher education. Oxford University Press.

Kladder, J. R. (2017). Re-envisioning music teacher education: A comparison of two undergraduate music education programs in the US. [Doctoral dissertation, University of South Florida]. Scholar Commons. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/6719.

Kladder, J. (2019). Re-envisioning music teacher education: An investigation into curricular change at two undergraduate music education programs in the US. Arts Education Policy Review, 1–19.

Kratus, J. (2007). Music education at the tipping point. Music Educators Journal, 94(2), 42–48.

Kratus, J. (2016). Songwriting: A new direction for secondary music education. Music Educators Journal, 102(3), 60–65.

Krikun, A. (2017). Teaching the ‘people’s music’ at the ‘people’s college’: Popular music education in the junior college curriculum in Los Angeles, 1924–55. Journal of Popular Music Education, 1(2), 151–164.

Lebler, D. (2007). Student-as-master? Reflections on a learning innovation in popular music pedagogy. International Journal of Music Education, 25(3), 205–221.

Lebler, D. (2008). Popular music pedagogy: Peer learning in practice. Music Education Research, 10(2), 193–213.

Little Kids Rock. (2020). https://www.littlekidsrock.org.

Marade, A. A., Gibbons, J. A., & Brinthaupt, T. M. (2007). The role of risk‐taking in songwriting success. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 41(2), 125–149.

McIntyre, P. (2008). Creativity and cultural production: A study of contemporary Western popular music songwriting. Creativity Research Journal, 20(1), 40–52.

McIntyre, P. (2016). Songwriting as a creative system in action. In McIntyre, P., Fulton, J., & Paton, E. (Eds.), The creative system in action: Understanding cultural production and practice (pp. 47–59). Palgrave Macmillan.

McIntyre, P. (2019). Taking creativity seriously: Developing as a researcher and teacher of songwriting. Journal of Popular Music Education, 3 (1), 67–85.

Modern Band. (2019). In Little Kids Rock website. https://www.littlekidsrock.org.

Moir, Z., Powell, B., & Smith, G. D. (Eds.). (2019). The Bloomsbury handbook of popular music education: Perspectives and practices. Bloomsbury Academic.

NAfME All-National Honor Ensembles. (n.d.). https://nafme.org/programs/all-national-honor-ensembles/

North, A. C., Hargreaves, D. J., & O’Neill, S. A. (2000). The importance of music to adolescents. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 70(2), 255–272.

O’Flynn, J. (2009), Review of Lucy Green, Music, informal learning and the school: A new classroom pedagogy (2008). Journal of the Society for Musicology in Ireland, 5, 109–113.

Pattison, P. (2011). Songwriting without boundaries: Lyric writing exercises for finding your voice. F+W media, inc.

Perkins, D. (1999). The many faces of constructivism. Educational leadership, 57(3), 6–11.

Powell, B., & Burstein, S. (2017). Popular music and Modern Band principles. In G. D. Smith, Z. Moir, M. Brennan, S. Rambarran, & P. Kirkman (Eds.). The Routledge research companion to popular music education (pp.243–54). Routledge.

Powell, B., Krikun, A., & Pignato, J. M. (2015). “Something’s Happening Here!”: Popular Music Education in the United States. IASPM@Journal 5(1), 4–22.

Randles, C. (2009). ‘That’s my piece, that's my signature, and it means more . . . ’: Creative identity and the ensemble teacher/arranger. Research Studies in Music Education, 31(1), 52–68.

Randles, C. (2012). Music teacher as writer and producer. Journal of Aesthetic Education, 46(3), 36–52.

Randles, C. (Ed.). (2014). Music education: Navigating the future. Routledge.

Randles, C. (2018). Modern band: A descriptive study of teacher perceptions. Journal of Popular Music Education, 2(3), 217–230.

Reimer, B. (1989). A philosophy of music education (vol. 2). Prentice Hall.

Reinhert, K. (2019). Lyric approaches to songwriting in the classroom. Journal of Popular Music Education, 3(1), 129–139.

Riley, P. E. (2012). Exploration of student development through songwriting. Visions of Research in Music Education, 22, 1–21.

Robinson, K., & Lee, J. R. (2011). Out of our minds. Tantor Media, Incorporated.

Rodriguez, C. X. (2004). Popular music in music education: Toward a new conception of musicality. In C. X. Rodriguez (Ed.), Bridging the gap: Popular music and music education (pp. 13–27), MENC.

Saarikallio, S., & Jaakko, E. (2007). The role of music in adolescents’ mood regulation. Psychology of Music, 35(1), 88–109.

Smith, G. D., Moir, Z., Brennan, M., Rambarran, S., & Kirkman, P. (Eds.). (2017). The Routledge research companion to popular music education. Routledge.

Sternberg, R. J. (Ed.). (1999). Handbook of creativity. Cambridge University Press.

Tobias, E. S. (2012). Hybrid spaces and hyphenated musicians: Secondary students’ musical engagement in a songwriting and technology course. Music Education Research, 14(3), 329–346.

Tobias, E. S. (2013). Composing, songwriting, and producing: Informing popular music. Research Studies in Music Education, 35(2), 213–237.

Toynbee, J. (2016). Making popular music: Musicians, creativity and institutions. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Vasil, M. (2015). Integrating popular music and informal music learning practices: A multiple case study of secondary school music teachers enacting change in music education. [Doctoral dissertation, West Virginia University]. Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 6868. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/6868

Washburn, R. (1960). The Young Composers Project in Elkhart. Music Educators Journal 47(1), 108–109.

Webster, P. R. (2011). Construction of music learning. In Colwell, R. and Webster, P. R. (Eds.), MENC handbook of research on music learning: Volume 1 (35–83), Oxford University Press.

Weiss, L., Abeles, H. F., & Powell, B. (2017). Integrating popular music into urban schools: Examining students’ outcomes of participation in the Amp Up New York City music initiative. Journal of Popular Music Education, 1(3), 331–356.

Werner, R. J. (1979). The Yale seminar: From proposals to programs. Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education, 60, 52–58.

West, A. (2016). The Art of Songwriting. Bloomsbury Publishing.

What is Modern Band?. (2018). https://www.littlekidsrock.org/what-is-modern-band/

Wiggins, J. D., Blair, D., Ruthmann, S. A., & Shively, J. (2005). A heart to heart about music education practice. In Proceedings of the Mountain Lake Colloquium for Teachers of General Music Methods.

Williams, D. A. (2011). The elephant in the room. Music Educators Journal, 98(1), 51–57.

Williams, D. A. (2014). Another perspective: The iPad is a REAL musical instrument. Music Educators Journal, 101(1), 93–98.

Williams, D. A. (2015). The baby and the bathwater. College Music Symposium, 55.

Williams, D. A., & Kladder, J. R. (2019). The Learner-centered music classroom: Models and possibilities. Routledge.

Williams, K., & Williams, J. A. (Eds.). (2016). The Cambridge companion to the singer-songwriter. Cambridge University Press.

Woody, R. H. (2007) Popular music in school: Remixing the issues. Music Educators Journal, 93(4), 32–37.

Woody, R. H. and Lehmann, A. C. (2010). Student musicians’ ear-playing ability as a function of vernacular music experiences. Journal of Research in Music Education, 58(2), 101–115.