Abstract

It is well known that Alban Berg drew heavily from both the musical material and dramatic themes of Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde (1857–59) in his opera Lulu (1929–35, completed by Friedrich Cerha in 1979). This article provides an overview of Berg’s history of borrowing from Wagner, followed by in-depth readings of two underexplored quotations from his opera. The first of these is a concealed quotation displaying programmatic strategies analogous to those found in Berg’s other works from the late 1920s (the Lyric Suite and Der Wein in particular); the second, composed years later for the final scene of Lulu, betrays a shift in Berg’s creative priorities, reflecting both the changes in his personal life and the new political climate in which he worked.

Vincent P. Benitez

A veritable mountain of scholarship surrounds Alban Berg’s opera Lulu (1929–35, completed by Friedrich Cerha in 1979), ranging from dense, analytical explications of Berg’s serial procedures to cultural-historical readings of the opera in the context of interwar Vienna.1For the former, see Hall (1996), Headlam (1996), and Perle (1985). For the latter, see Jarman (2022/1979), Floros (2008), and Notley (2020). Regardless of the author’s approach, one feature of Lulu that rarely escapes mention is its kinship with Richard Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde (1857–59). Thomas Mann noted “Tristan-like effects” (1984, 278) after viewing the two-act premiere of Lulu in 1937, and critics such as Holloway (2003) and Conrad (2002) have followed suit in comparing the two operas. Moreover, scholars have been keen to point out more general similarities between the two works, such as shared dramatic themes or the use of leitmotifs common to both. There is likewise no shortage of commentary on the musical borrowing from Tristan in Lulu, although only a few such examples are discussed with any regularity. This article compares two rarely discussed Tristan quotations from the respective first and final scenes of Lulu, in the context of Berg’s late style, exploring how these short excerpts provide a window into Berg’s creative process in the respective early and late stages of composing the opera.

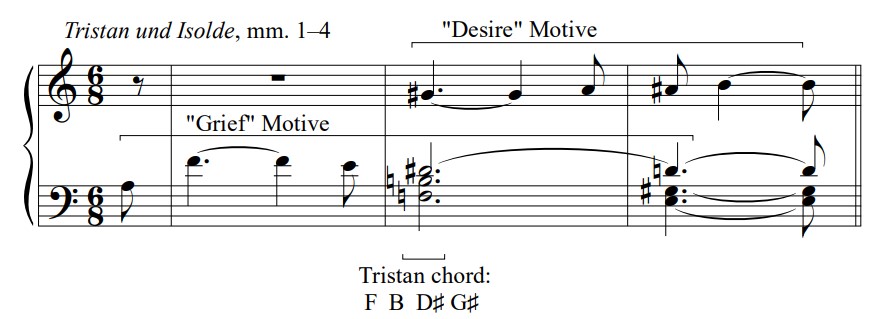

Before exploring Berg’s quotations from Tristan in Lulu, it is helpful to establish a baseline understanding of Berg’s practice of borrowing from Wagner in his earlier pieces. Floros (2008) and Esslin (1990) have argued that Berg used the music of Tristan in his first mature works to symbolize his once disallowed relationship with his eventual wife, Helene. Berg likely found the opera especially poignant in the years before their 1911 marriage, which, reminiscent of Robert and Clara Schumann’s, was long opposed by Helene’s father. Berg (1971, 33) even addressed Helene as “[his] Isolde” in a 1908 letter, betraying his self-identification with the opera’s protagonists. Berg’s Four Songs, op. 2 (1908–9)—a song cycle, his first work officially dedicated to Helene—begins, Naude (1997, 52) suggests, with a quotation of the opening bars from Tristan, alongside an apparent cipher for their initials (see Examples 1a and 1b for a comparison of the opening measures of Tristan with those of Berg’s op. 2, no. 1). His String Quartet, op. 3, also composed during this courtship, may likewise include material from Wagner’s opera.2For discussions of the possible quotations from Tristan in this piece, see Floros (1992, 155) and Pople (1997, 77–81).

Example 1a. Wagner, Tristan und Isolde, mm. 1–4

Example 1b. Programmatic elements in Berg’s op. 2, no. 1, mm. 2–4

Although there is little evidence of borrowing from Wagner’s opera in Berg’s music composed during the next fifteen years, after 1925, the music of Tristan returned to the forefront of his imagination. It is generally assumed that the cause of this creative shift was the start of his love affair with Hanna Fuchs-Robettin (1896–1964), a relationship sustained through private letters until Berg’s death in 1935.3Floros (2008, 4) explains that the pair relied upon their mutual friends (among them, Theodor Adorno and Alma Mahler) to deliver their correspondence in secret. The first clear instance of a Tristan quotation from this period appears in Berg’s Lyric Suite (1925), a string quartet secretly dedicated to Fuchs.4See especially Perle (1995), who “discovered” the secret dedication. This piece features an unmistakable, “verbatim” presentation of the first four bars of Tristan, as well as a number of other paraphrased motives from Wagner’s opera that are somewhat less conspicuous.5For discussions of additional Tristan quotations in the Lyric Suite, see Floros (1992, 280–85) and DeVoto (1995, 151). Just as Helene’s “musical initials” had at times been embedded in Tristan motives in Berg’s earlier works, borrowed material from Tristan in Berg’s late music often appears in conjunction with symbols for Berg and Fuchs: musical ciphers for their initials (A and B♭ [AB] and B and F [HF]), and the numbers he associated with each. A well-known numerological zealot, Berg developed a superstitious fascination with the number 23, believing it had played an outsize role in his life.6Berg’s near obsession with the number 23 is in part the result of reading Wilhelm Fliess’s Von Leben und Tod. Jarman (1990, 183) explains, “Berg seems to have become acquainted with Fliess’s work in the summer of 1914, by which time he had already noted ‘the strange coincidences surrounding the number 23’ and had persuaded himself that the number played an important role in his life.” References to this number are found throughout his late works, as well as to the number 10, which he associated with Hanna Fuchs.7In one of his private letters to Fuchs, for example, Berg mentions what he believed to be the fateful significance of his train ticket number 1023 from his trip back to Vienna after initially meeting her. See Floros (2008, 25). The complete letter from July 1925 is in Floros (2008, 18–27).

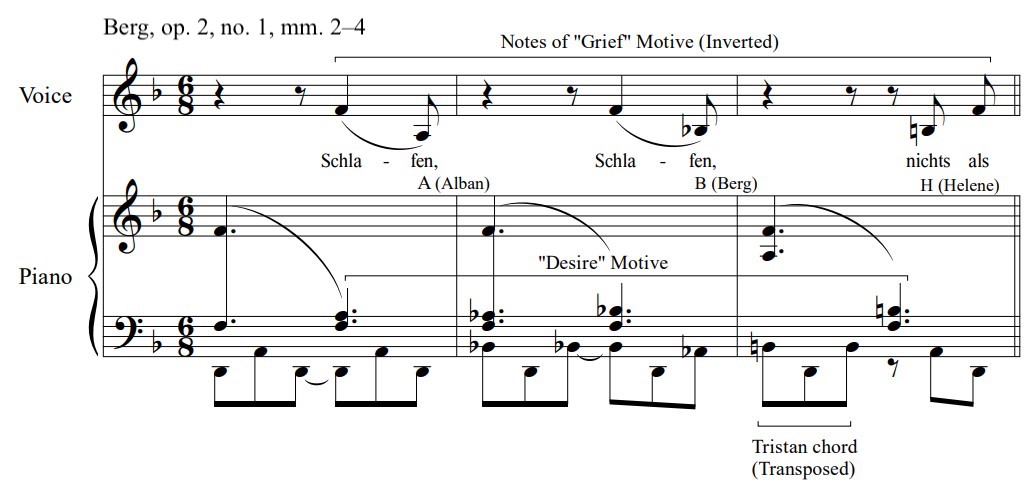

The most frequently discussed Tristan quotations in Lulu appear in two of the title character’s most emotionally charged love scenes: her conversations with Dr. Schӧn in Act I, and her Act 2 duet with Alwa. Regarding the former, Lochhead (1999, 236) observes that “[a]s Lulu articulates the nature of the bonds that link her with Schön, the music alludes to the melodic and harmonic profile of the Prelude from Tristan und Isolde and insinuates the sense of romantic longing that attaches to the work.”8See also Baragwanath (1999, 81) for a discussion of the reprise of this passage at the conclusion of Act I of Lulu. Regarding the latter, while several authors note Berg’s clear quotation of the “Tristan chord” (Example 2) in this scene as Alwa declares his love for Lulu, dos Santos (2003, 43–75) offers the most detailed reading of the complete number, demonstrating that allusions to Tristan permeate the scene.

Example 2. Tristan chord in Lulu, Act II, mm. 335–36

Lulu’s romantic encounters with these two characters are perhaps the most intuitive places to look for such programmatic quotation. As Schӧn is the most central figure in Lulu’s romantic life—the closest to being the Tristan to her Isolde—it is dramatically effective to allude to Wagner’s opera when they privately interact. Alwa, rather, is an overtly autobiographical character; as Berg identified with the Tristan character, it follows that his on-stage avatar should likewise feel such a kinship with Wagner’s tragic hero.9The autobiographical elements of Alwa’s character are well documented in the secondary literature. Most crucially, Alwa is a composer, like Berg himself. Hall (1996, 149) discusses the relationship between Alwa and Tristan at length: “Many sketches for [this scene] suggest that on some level Berg associated the character Alwa with Tristan in Wagner’s opera.... Berg specifies that Alwa, like Tristan, is to be a Heldentenor, to which he adds ‘Tristan.’” Yet, even if these scenes are the passages in which the clearest borrowed material from Tristan und Isolde can be found—and they likely are—given the remarkable influence that Wagner’s work had upon Berg, it is reasonable to wonder if these quotations are merely the tip of the proverbial iceberg. I will demonstrate that there remains a wealth of borrowed material from Wagner’s opera that has received remarkably little attention.

Tristan Quotations and the “Secret Program” Early in Lulu

Within the very first scene of the opera, in the canon duet between Lulu and the Painter, there is an intriguing cluster of quotations from Tristan und Isolde, which (to my knowledge) has not been discussed by any other author. Perhaps it has widely evaded notice because it is neither “literal” (like the aforementioned Tristan chord that appears in the Act II Alwa/Lulu duet), nor does it sonically evoke a more romantic, Wagnerian idiom (as many passages of the opera do). In other words, it is conspicuous to neither the eye nor the ear. Nevertheless, there is more than sufficient evidence of a “secret” program here. The clearest borrowed element in this passage is the half-diminished seventh chord in m. 162, a harmony enharmonically equivalent to Wagner’s famous Tristan chord. Knowing of Berg’s programmatic use of this sonority elsewhere in his late works, it is likely that this chord does indeed reference Wagner’s opera—especially when one considers the other elements that surround it.

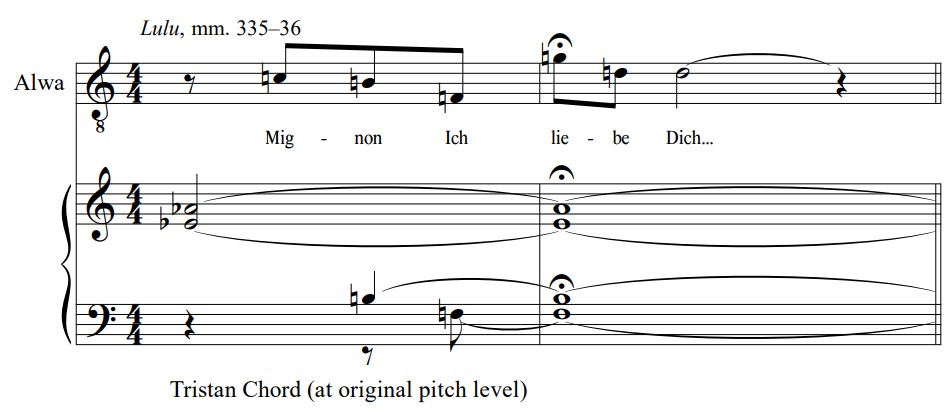

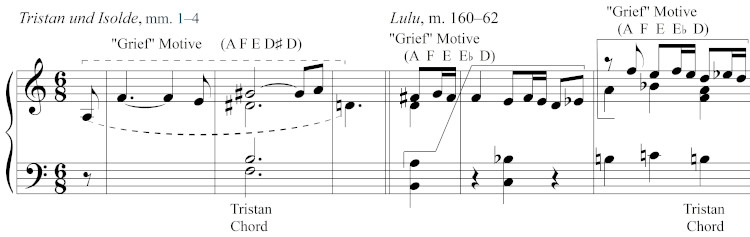

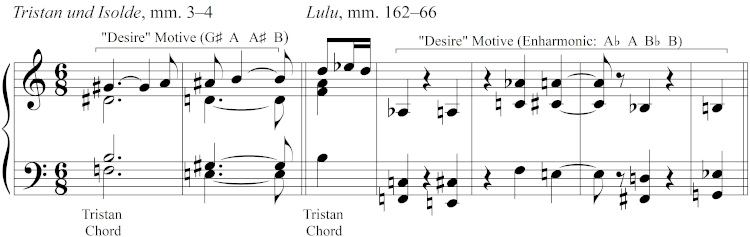

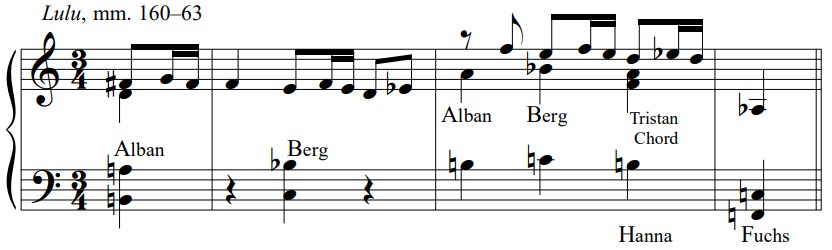

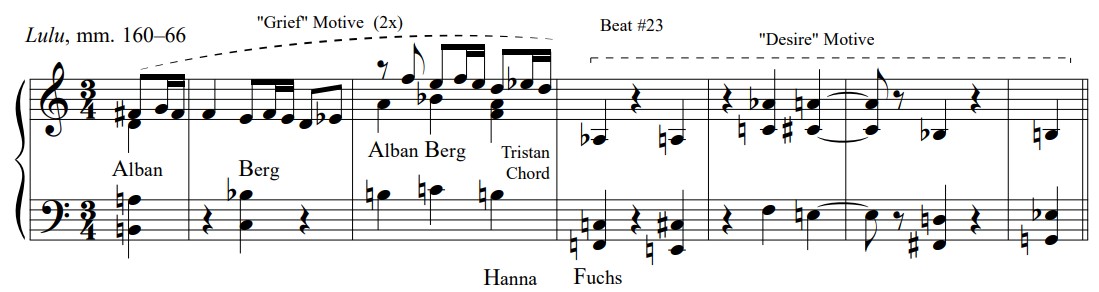

First, notice that the upper two voices of the texture in mm. 160–62 of Lulu closely resemble the opening cello melody, or “Grief motive,” from Tristan (Example 3), while the oboe melody from mm. 3–4 of Tristan, or “Desire motive,” appears in Lulu as the highest melodic voice right after the apparent quotation of the Tristan chord (Example 4) Also note that the bass progression from F to E in mm. 3–4 of Tristan likewise appears in the lowest voice of this passage from Lulu (mm. 163–65).

Example 3. Motives from Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde in Berg’s Lulu, mm. 160–62

Example 4. Motives from Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde in Berg’s Lulu, mm. 162–66

Next, notice that ciphers for both Berg and Fuchs appear in this passage (Example 5). The A-B♭ for Berg’s name appears twice, while the H-F for Fuchs’s name follows immediately after; the lowest voice of the aforementioned Tristan chord quotation is a B (“H,” according to German convention), and an F appears on the very next beat. (One might also find both of her initials contained within the Tristan chord, which may explain why Berg selected this transposition of it.) These ciphers found alongside the music of Tristan seemingly portray Berg’s desire for Fuchs, Tristan’s for Isolde, and the Painter’s adulterous lust for Lulu.

Example 5. Ciphers and the Tristan chord in Berg’s Lulu, mm. 160–63

Third, alongside the Tristan quotations and musical initials, Berg’s number, 23, can readily be found here (Example 6). The 23rd beat of the canon follows Fuchs’s initials directly, which means that the cipher for Fuchs is surrounded by two symbols for Berg: his initials, and his number, perhaps “embracing” her, as the Painter does Lulu at the end of the duet. Fuchs’s number may likewise be included here; this complete section is 30 measures long, which is a multiple of her number, 10.10Three (the quotient of 30 and 10) is another of Berg’s “favorite” numbers. As Berg explained in his “open letter” about the Chamber Concerto (see Reich 1937, 86-91), the number 3 has the same symbolic and structural significance that 23 and 10 do in Lulu. To suggest that this is an indirect reference to her number will surely seem unconvincing to those unfamiliar with Berg’s enthusiasm for numerology, yet the regularity with which Berg alludes to these numbers in Lulu, in Hall’s (1996, 247) words, “bordered on the obsessive.”11Hall (1996, 247) continues: “[N]othing seemed to delight [Berg] more, for instance, than incorporating his number of fate, 23, into the music of Lulu, and the sketches are filled with exuberant annotations.” Berg has a documented history of using multiples (and even fractions) of the numbers 23 and 10 to shape everything from tempo markings to measure counts of large-scale sections of his late works.12The Lyric Suite is a case in point; most of tempo markings are derived from the numbers 23 or 10, and the total number of measures in each movement is multiple of 23 and/or 10. For example, the first and fourth movement each have 69 measures (divisible by 23), the second movement has 150 bars (divisible by 10), and the fifth movement has 430 measures (divisible by both 23 and 10).

Example 6. Programmatic Elements in Berg’s Lulu, mm. 160–66

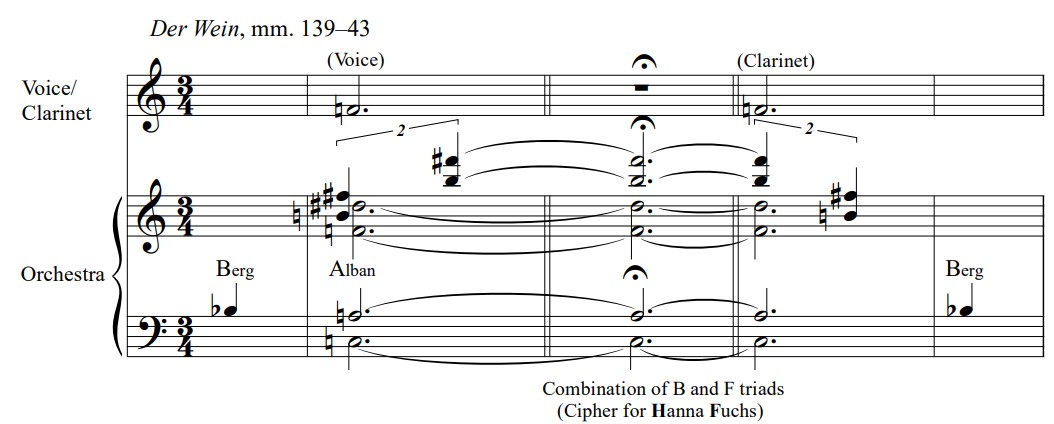

While the quotation of Tristan in this passage (and what it signifies) finds precedent in the Lyric Suite, the use of autobiographical symbols here is corroborated by an analogous example in Der Wein (1929), which was composed not long after Berg had completed this passage of Lulu (Example 7).13Both passages were likely composed in 1929. Pople (1990, 213) explains that Berg suspended work on Lulu to compose Der Wein, because of “a financially attractive commission” of 5,000 schillings.” In both works, Berg seems to encircle Fuchs’ initials with symbols for himself. In Der Wein, a B (H)/F polychord appears at the climax of the aria—a sonority—Berg privately confessed—that was a cipher for Fuchs’s initials.14Footnote text Notice in Example 7 that this chord likewise (perhaps coincidentally) includes A, the initial for Berg’s given name, and that B♭ appears before the B/F chord, and is the first note to reenter after it. These two appearances of B♭, I believe, do represent Berg’s surname, because they not only flank the sonority for Fuchs’s initials but also appear 10 beats apart—Berg’s name, “guided” by Fuchs’s number.

Example 7. Ciphers in Berg’s Der Wein, mm. 139–43

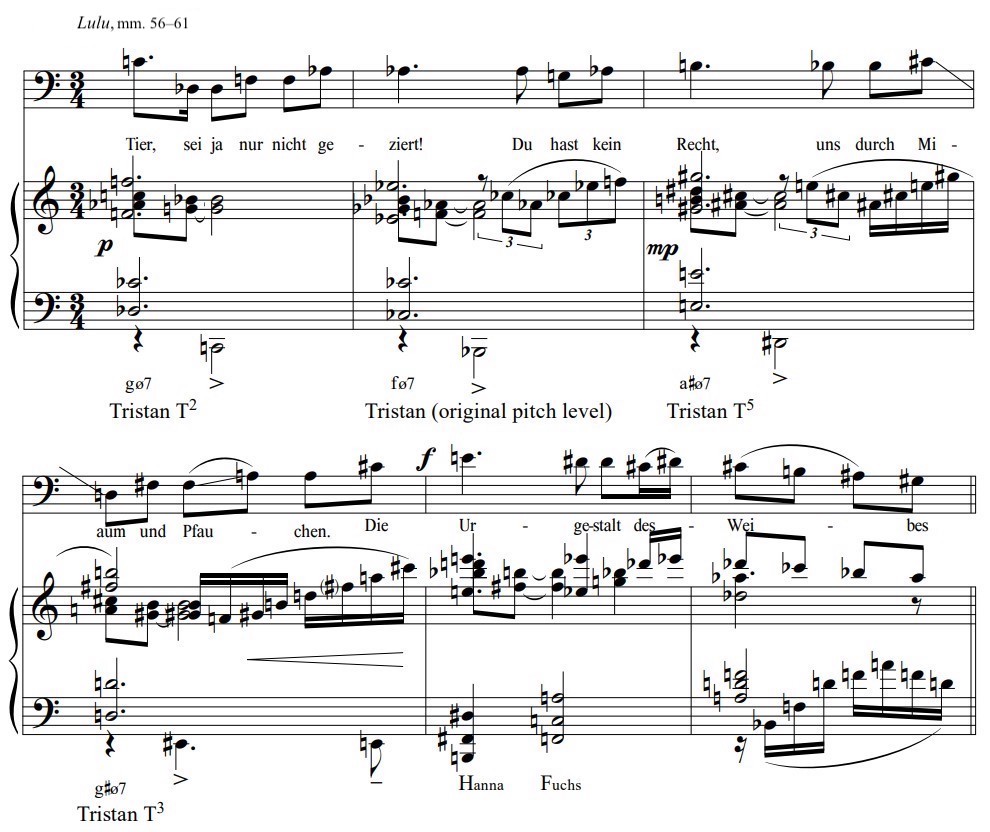

Other passages—perhaps many more—from the first scenes of Lulu likely feature programmatic content analogous to the excerpt discussed above, combining quotations from Tristan and autobiographical symbols. The clearest example of which I am aware can be found in the music that serves as the introduction of the Lulu character in the opera’s prologue. Perle (1983, 139) suggests that a cipher for Hanna Fuchs’s name appears in this passage as the narrator calls Lulu “the primal form of woman” (“die Urgestalt des Weibes”).15Perle (1983, plate 12) also demonstrates that Berg placed this text at the bottom of the first page in his original libretto, with these words typed with an extra space between each of the letters, suggesting the emphasis he envisioned for this text. In Example 8, as in the Painter’s canon, the notes B (H) and F appear on consecutive bass notes. Although this assertion seems plausible on its own—Berg surely could not resist the opportunity to liken his sometime muse to his title character—it becomes more convincing still when one considers that Berg may be alluding to Tristan in this passage as well. Note that each of the four measures immediately preceding Fuchs’s initials includes a different transposition of the Tristan chord.16Furthermore, several motives in this passage resemble figures that appear in mm. 17–21 of the Tristan Prelude. Of greatest aural salience, the appoggiatura figure that accompanies Lulu’s arrival on stage in m. 44 features the same combination of pitch classes in the upper voices as can be found in m. 17 of Wagner’s opera. See Orosz (2013, 201–4) for a more detailed discussion of this passage.

Example 8. Tristan chords and cipher in Berg’s Lulu, mm. 56–61

Interpreting the Tristan Chord at the End of Lulu

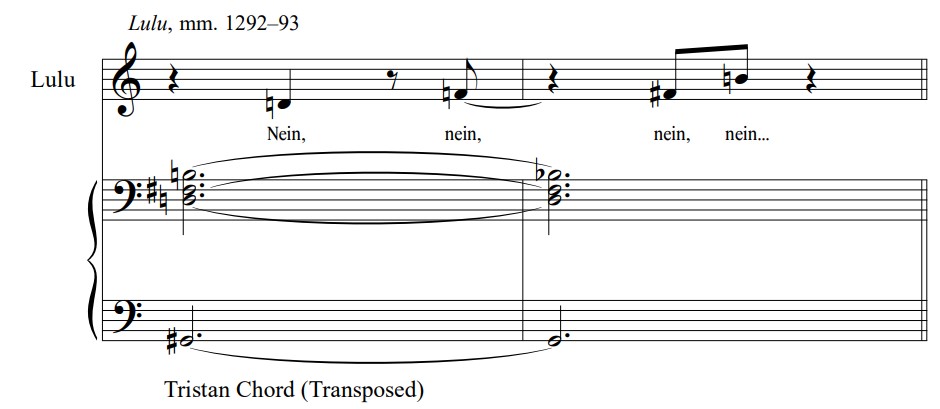

The first two acts of Lulu, at least as far as “covert” programmatic elements are concerned, seem very much in line with Berg’s other works from the latter half of the 1920s. Another quotation of the Tristan chord from near the end of the third act, however, invites a different interpretation. This harmony, likely the final Tristan chord in the opera, appears when Lulu, now a prostitute, begs Jack the Ripper (a role performed by the same actor portraying Schön) to spare her life (Example 9). DeVoto (1995, 152) notes the “bitter irony” in referencing Wagnerian love-death as Lulu is brutally murdered—no less by a character who reminds the audience of the only man she ever claimed to have loved.

Example 9. Tristan chord in Lulu, Act III, mm. 1292–93

This quotation, of course, is not wholly unrelated to the one found in the duet discussed above. The programmatic significance of each—or, following Nattiez (1990), signification on the neutral (or immanent) level—is abundantly clear. When Lulu is involved in one of her many romantic entanglements, or is merely presented as an object of desire, the dramatic justification for quoting Tristan is no mystery. Nevertheless, a poietic reading of these passages, or a theory about why Berg so regularly turned to the music of Tristan when composing Lulu, leads us down different paths.

The autobiographical symbols for Berg and Fuchs that appear alongside material from Tristan in both the prologue and the canon duet suggest that Berg equated the love narratives in Lulu with those of his own life. Indeed, the salutes to Wagner’s Tristan, overt or veiled, were clearly an important component of Berg’s programmatic imagination in his work during the late 1920s, and it is reasonable to assert that the habitual borrowing from Tristan during this period was inspired by his affiliation with Hanna Fuchs. Floros (2008, 1) makes this argument with somewhat less reserve, suggesting that this relationship had “an enormous impact on [Berg’s] work,” to the extent that “[c]ompositions like the Lyric Suite and the concert aria Der Wein—probably also Lulu—would not have come about without Fuchs.” Regardless, even if much of the material from Tristan in Berg’s late works does refer to Hanna Fuchs, I do not argue, as Perle does, that this is evidence of lasting marital discord between the Bergs. To be clear, I seek neither to affirm nor deny any arguments about Berg’s romantic life. Rather, I invite the reader to draw their own conclusion by reading his correspondence, keeping in mind what Schroeder (1999, 187) calls Berg’s “exceptionally skillful epistolary masks.” One should also read cautiously, dos Santos (2014, 38) suggests, because the Berg-Fuchs correspondence is one-sided, as Fuchs’s letters either “were destroyed or are yet to be found.” Consider Adorno’s position as well: in a letter to Berg’s widow, he suggested that Berg “didn’t write the Lyric Suite because he fell in love with Hanna Fuchs, but fell in love with [her] in order to write the Lyric Suite”17Quoted in Jarman (1999, 177).—that she was nothing more than “a necessary muse for Berg” (Schroder 1999, 234).

The final Tristan chord in Lulu, rather, given the lack of autobiographical symbols surrounding it—and the fact that Berg’s correspondence with Fuchs had cooled significantly by the time he was at work on Act III—suggests that this quotation may stem from a different source of inspiration. DeVoto (1995, 153) calls it “a muted backwards glance” to “the legacy of Wagner’s revolution in operatic structure,” or an homage to a composer Berg deeply admired. It is true that Berg, at least as a young man, idolized Wagner’s creative genius, nigh worshiping both the man and his works. Countless anecdotes attest to this: (1) His early letters to Helene are filled with words of cultish praise for Wagner; (2) Berg’s nephew (Erich Alban Berg 1985, 14) suggests that Alban developed this admiration growing up in a household in which his older brother, a decidedly amateur musician, regularly sang through entire Wagner operas “from beginning to end” while accompanying himself at the piano; and (3) Adorno claimed—presumably with some exaggeration—that Berg would rush toward a piano whenever he laid eyes on one to play the famous Tristan chord.18Both Baragwanath (1999, 62) and Naudé (1997, 19) cite this anecdote from Jarman’s reading of Adorno’s unpublished reminiscences. In other words, we might choose to interpret this borrowing as a final salute to a composer two generations his senior.

Such a reading, however, conveniently ignores the circumstances in Berg’s life during the 1930s. It is well known that after the Nazis rose to power in Germany in 1933, Berg’s music came under attack as “degenerate art.” In a letter to Webern from that year, he expressed his prescient “fear that the Nazis will take over [Austria] too, that is, our government won’t be strong enough to stop it.”19Quoted in Hall (1996, 55). Performances of Wozzeck were banned in German Europe, causing Berg much financial and emotional trauma. The piece that once made him rich and famous was gradually making him an enemy of the state. Meanwhile, the music of Wagner was lionized as one of the crowning achievements of German civilization. These extraordinary circumstances surely must have complicated his feelings about Wagner, and it is difficult to imagine that Berg could have remained uncritical of his sometime hero once the political climate had grown less hospitable.

Berg reportedly once said that he “wished to burn the Lulu score whenever he heard Tristan und Isolde” (Baier 1989, 599). Rather than burn Lulu in frustration, perhaps he sought to shatter the legacy of Tristan instead and erase the work from cultural memory through his own work. Berg never set out to recreate Tristan—he aimed to take it to its next level of development, offering a didactically clear example of the final two of Bloom’s (1973) six “revisionary ratios” in which the “anxiety of influence” takes shape: Askesis and Apophrades.20See Bloom (1973, 15–16) for complete definitions of these terms, as well as the other four “revisionary ratios. Respecting the former, Bloom (1973, 121) describes it as a “match-to-the-death with the dead,” in which a poet metaphorically wrestles with a prominent predecessor to create a space for their own work. The latter, apophrades, fits almost eerily well, in which “later poets, confronting the imminence of death, work to subvert the immortality of the precursors, as though any one poet’s afterlife could be metaphorically prolonged at the expense of another” (Bloom 1973, 151).

The final Tristan chord in Lulu, then, is not a “muted, backward glance,” but a clue that the music of Tristan was no longer an emotional catalyst for Berg. Instead, it became an albatross—a sign of Berg’s struggle with Wagner. Even though Tristan und Isolde likely served as a model, even an inspiration for Berg during the early stages of composing Lulu, his aesthetic worldview clearly shifted during his final years. Employing the Tristan chord as Jack fatally stabs Lulu betrays Berg’s desire to rip the ghost of Wagner from his back, and to silence Wagner’s heavy footsteps behind him, once and for all.

Notes

1. For the former, see Hall (1996), Headlam (1996), and Perle (1985). For the latter, see Jarman (2022/1979), Floros (2008), and Notley (2020).

2. For discussions of the possible quotations from Tristan in this piece, see Floros (1992, 155) and Pople (1997, 77–81).

3. Floros (2008, 4) explains that the pair relied upon their mutual friends (among them, Theodor Adorno and Alma Mahler) to deliver their correspondence in secret.

4. See especially Perle (1995), who “discovered” the secret dedication.

5. For discussions of additional Tristan quotations in the Lyric Suite, see Floros (1992, 280–85) and DeVoto (1995, 151).

6. Berg’s near obsession with the number 23 is in part the result of reading Wilhelm Fliess’s Von Leben und Tod. Jarman (1990, 183) explains, “Berg seems to have become acquainted with Fliess’s work in the summer of 1914, by which time he had already noted ‘the strange coincidences surrounding the number 23’ and had persuaded himself that the number played an important role in his life.”

7. In one of his private letters to Fuchs, for example, Berg mentions what he believed to be the fateful significance of his train ticket number 1023 from his trip back to Vienna after initially meeting her. See Floros (2008, 25). The complete letter from July 1925 is in Floros (2008, 18–27).

8. See also Baragwanath (1999, 81) for a discussion of the reprise of this passage at the conclusion of Act I of Lulu.

9. The autobiographical elements of Alwa’s character are well documented in the secondary literature. Most crucially, Alwa is a composer, like Berg himself. Hall (1996, 149) discusses the relationship between Alwa and Tristan at length: “Many sketches for [this scene] suggest that on some level Berg associated the character Alwa with Tristan in Wagner’s opera. . . . Berg specifies that Alwa, like Tristan, is to be a Heldentenor, to which he adds ‘Tristan.’”

10. Three (the quotient of 30 and 10) is another of Berg’s “favorite” numbers. As Berg explained in his “open letter” about the Chamber Concerto (see Reich 1937, 86-91), the number 3 has the same symbolic and structural significance that 23 and 10 do in Lulu.

11. Hall (1996, 247) continues: “[N]othing seemed to delight [Berg] more, for instance, than incorporating his number of fate, 23, into the music of Lulu, and the sketches are filled with exuberant annotations.”

12. The Lyric Suite is a case in point; most of tempo markings are derived from the numbers 23 or 10, and the total number of measures in each movement is multiple of 23 and/or 10. For example, the first and fourth movement each have 69 measures (divisible by 23), the second movement has 150 bars (divisible by 10), and the fifth movement has 430 measures (divisible by both 23 and 10).

13. Both passages were likely composed in 1929. Pople (1990, 213) explains that Berg suspended work on Lulu to compose Der Wein, because of “a financially attractive commission” of 5,000 schillings.”

14. Berg explains in a 1929 letter to Fuchs: “[W]hom else does it concern but you, Hanna, when I say (in ‘The Wine of Lovers’): ‘Come, sister, laid breast to breast, Let us flee without rest or stand, To my dreams’ Elysian land,’ and these words die away in the softest accord of H [B] and F major!” Quoted in Floros (2008, 56).

15. Perle (1983, plate 12) also demonstrates that Berg placed this text at the bottom of the first page in his original libretto, with these words typed with an extra space between each of the letters, suggesting the emphasis he envisioned for this text.

16. Furthermore, several motives in this passage resemble figures that appear in mm. 17–21 of the Tristan Prelude. Of greatest aural salience, the appoggiatura figure that accompanies Lulu’s arrival on stage in m. 44 features the same combination of pitch classes in the upper voices as can be found in m. 17 of Wagner’s opera. See Orosz (2013, 201–4) for a more detailed discussion of this passage.

17. Quoted in Jarman (1999, 177).

18. Both Baragwanath (1999, 62) and Naudé (1997, 19) cite this anecdote from Jarman’s reading of Adorno’s unpublished reminiscences.

19. Quoted in Hall (1996, 55).

20. See Bloom (1973, 15–16) for complete definitions of these terms, as well as the other four “revisionary ratios.

References

Baragwanath, Nicholas. 1999. “Alban Berg, Richard Wagner, and Leitmotivs of Symmetry,” Nineteenth Century Music 23, no 1: 62–83.

Baier, Christian. 1989. “Fritz Heinrich Klein: Der ‘Mutterakkord’ im Werk Alban Bergs.”Österreichische Musik Zeitschrift, 44: 585–600.

Berg, Alban. 1971. Letters to His Wife. Edited, translated, and annotated by Bernard Grun. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Berg, Erich Alban. 1985. Der unverbesserliche Romantiker: Alban Berg, 1885–1935. Vienna: Österreichischer Bundesverlag.

Bloom, Harold. 1973. The Anxiety of Influence. New York: Oxford University Press.

Conrad, Peter. 2002. “In bed with Madonna.” New Statesman 131/4588 (May 20th), 42–43.

DeVoto, Mark. 1995. “The Strategic Half-diminished Seventh Chord and The Emblematic Tristan Chord: A Survey from Beethoven to Berg,” International Journal of Musicology 4: 139–53.

dos Santos, Silvio J. 2014. Narratives of Identity in Alban Berg’s Lulu. Rochester: University of Rochester Press.

Esslin, Martin. 1990. “Berg’s Vienna.” In The Berg Companion, edited by Douglas Jarman, 181–94. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1990.

Floros, Constantin. 1992. Alban Berg: Musik als Autobiographie. Wiesbaden: Breitkopf & Härtel.

———. 2008. Alban Berg and Hanna Fuchs. Translated by Ernest Bernhardt-Kabish. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2008.

Hall, Patricia. 1996. A View of Lulu Through the Autobiographical Sources. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Headlam, David. 1996. The Music of Alban Berg. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1996.

Holloway, Robin. 2003. “Lulu,” On Music: Essays and Diversions 1963–2003. London: Claridge Press.

Jarman, Douglas. 1990. “Alban Berg, Wilhelm Fliess, and the Secret Programme of the Violin Concerto.” In The Berg Companion, edited by Douglas Jarman, 181–94. Boston: Northeastern University Press.

———. 1997. “Secret Programmes.” In The Cambridge Companion to Alban Berg, ed. Anthony Pople, 165–79. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

———. 2022/1979. The Music of Alban Berg. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press

Lochhead, Judy. 1999. “Hearing Lulu.” In Audible Traces: Gender, Identity and Music, edited by Elaine Barkin and Lydia Hamessley, 231–56. Zurich and Los Angeles: Cariciofoli.

Mann, Thomas. 1984. Diaries, 1918–1938. Translated by Richard and Clara Winston. London: Robin Clark.

Nattiez, Jean Jaques. 1990. Music and Discourse: Toward a Semiology of Music. Translated by Carolyn Abbate. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Naudé, Janet Joan. 1997. “Lulu, Child of Wozzeck and Marie: Towards an Understanding ofAlban Berg, ‘Master of the Smallest Link,’ through his Vocal and Dramatic Music.” PhD diss., University of Capetown.

Notley, Margaret. 2020. “Taken by the Devil”: The Censorship of Frank Wedekind and Alban Berg’s Lulu. New York: Oxford University Press.

Orosz, Jeremy. 2013. “Translating Music Intelligibly:” Musical Paraphase in the Long 20th Century,” PhD diss., University of Minnesota.

Reich, Willi. 1937. Alban Berg, mit Bergs eigenen Schriften und Beiträgen von Theodor Wiesengrund-Adorno und Ernst Krenek. Vienna: Herbert Reichner Verlag, 1937.

Perle, George. 1985. The Operas of Alban Berg. Vol. 2, Lulu. Berkeley and Los Angeles:University of California Press.

———. 1995. “The Secret Program of the Lyric Suite.” In The Right Notes: Twenty-Three Selected Essays by George Perle on Twentieth-Century Music. 75–102. Stuyvesant, NY: Pendragon Press.

Pople, Anthony. 1997. “In the Orbit of Lulu: The Late Works.” In The Cambridge Companion to Alban Berg, edited by Anthony Pople, 204–26. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schroeder, David. 1999. “Alban Berg.” In Schoenberg, Berg, and Webern: A Companion to the Second Viennese School, edited by Bryan Simms, 185–250. Westport: Greenwood Press.