Abstract

In 1882, Luise Adolpha Le Beau (1850–1927) won the first prize in an international competition in Hamburg, surprising the judges because of her gender. As a result, music journalists began publishing biographies of her across Germany, she received an honorary membership at the Mozarteum in Salzburg, and her opera Hadumoth was performed in Baden-Baden in 1894. In 1903, Ethel Smyth (1858–1944) became the first woman composer to have an opera performed at the Metropolitan Opera, with this production breaking their box office record for that year. Smyth was also the first female composer to receive a damehood and was awarded several honorary doctorates, including one from Oxford. Finally, Countess Dora Pejačević (1885–1923) is notable as one of the first Croatians to produce a symphony and a piano concerto, and according to her biographer Koraljka Kos (2008), she was also the first of her compatriots to delve deeply into chamber music.

In spite of such honors and breakthroughs during the lifetimes of these women composers, their music is seldom performed on today’s mainstream Classical music stages. This article seeks to broaden the listening public’s perspective by considering their achievements via an examination of three of their cello works: (1) Le Beau’s Cello Sonata in D Major, op. 17; (2) Smyth’s Sonata in A Minor, op. 5; and (3) Pejačević’s Sonata in E Minor, op. 35. There will be a brief overview of Romantic cello sonatas by composers who wrote for the genre roughly at the same age as these women, and an inquiry into possible reasons as to why their music has been excluded from the canon. Beyond the usual misogyny, other issues will be considered as to why these works are not better known today.

Vincent P. Benitez

In 1882, Luise Adolpha Le Beau (1850–1927) won first prize in an international competition in Hamburg, surprising the judges because of her gender. Consequently, music journalists began publishing biographies of her across Germany, she received an honorary membership at the Mozarteum in Salzburg, and her opera Hadumoth was performed in Baden-Baden in 1894. Nearly a decade later in 1903, Ethel Smyth (1858–1944) became the first woman composer to have an opera performed at the Metropolitan Opera. This production broke their box office record for that year. Smyth was also the first female composer to receive a damehood and was awarded several honorary doctorates, including one from Oxford. Finally, Countess Dora Pejačević (1885–1923) is notable as one of first Croatians to write a symphony and a piano concerto. According to her biographer Koraljka Kos (2008), she was also the first of her compatriots to delve deeply into chamber music.

Despite such honors and breakthroughs during these composers’ lifetimes, their music is rarely performed on today’s mainstream Classical music stages. This article seeks to broaden the listening public’s perspective by considering the achievements of these women through an examination of three of their cello works: (1) Le Beau’s Cello Sonata in D Major, op. 17; (2) Smyth’s Sonata in A Minor, op. 5; and (3) Pejačević’s Sonata in E Minor, op. 35. All three of these cello sonatas were written when these composers were in their late twenties, a fact that might be less remarkable if it were not that male composers of the most famous cello sonatas from this period also began writing roughly at this age. This similarity of age and maturity leads to an inquiry as to why the women’s music has been excluded from the canon. Factors beyond the expected misogyny—such as the lack of a network, the composer’s self-image and promotion, and early death—will be considered as additional reasons for obscurity.

Beginning with the five cello sonatas by Beethoven (written between the years of 1796 and 1815), the nineteenth century saw the rise of the cello sonata as a genre of equal voices, overshadowing earlier versions that featured a solo cello with figured bass. A roster of cello sonatas written before the age of thirty includes compositions by Beethoven (Sonatas in F Major and G Minor, op. 5, nos. 1 and 2, respectively, in 1796), Mendelssohn (Sonata in B♭ Major, op. 45 in 1838), Brahms (Sonata in E Minor, op. 38 in 1862–65), and Rachmaninoff (Sonata in G Minor, op. 19 in 1901). One might also include Schubert, whose sonata originally written for the arpeggione is played by cellists (Sonata in A Minor, D. 821 in 1824). The popularity of house concerts made this genre a natural choice for composers, and most of these sonatas originated as a result of the composer’s collaborations with colleagues, friends, or family members. As noted above, each cello sonata by the women discussed here was also written around the age of twenty-eight. However, this late-twenties stage of development was experientially different for women, since their musical education was often affected by gender restrictions.

In the case of Le Beau, she recounts different forms of public censure, from boys harassing her beneath her window as she practiced at home to stern friends of her parents who repeatedly discouraged her studies (Olson 1986, 283 and 291). Upon her father’s retirement in 1874, the family sought a better environment for her schooling in Munich. After waiting a year during which she was taught by a pupil at the Hochschüle, she was accepted as a student of renowned composition teacher Josef Rheinberger (1839–1901). Unfortunately, Le Beau was denied entrance to the other composition classes at the Hochschüle, due most likely to her gender. Despite such setbacks, the year 1878 was productive for Le Beau. She wrote her Cello Sonata in D Major, gave her debut recital presenting many of her own works, and began educating other young women through her rigorous program of piano and music theory lessons. (Forkert 2010, 2). She also wrote several other duos for strings and piano: the Violin Sonata in C Minor, op. 10, no. 1, published in 1882; Drei Stücke für Viola und Klavier, op. 26 and the Vier Stücke für Violoncello mit Klavierbegleitung, op. 24, both composed in 1881.

By 1882, in her thirty-second year, Le Beau had a falling out with Rheinberger, due to several conflicts, including her refusal to side with him in denouncing The New German School (Forkert 2010, 2). Nevertheless, she moved forward with her composing, submitting a piece that year to an international competition in Hamburg. The winning composition was her Vier Stücke für Violoncello mit Klavierbegleitung, op. 24. A collection of short showpieces written in a lighter style than her Cello Sonata, it is similar in tone to her collection for viola and piano. As she walked up to claim her prize, the startled judges crossed out “Herr” on the award and replaced it with “Fräulein” (Olson 1986, 284). That one of her notable accomplishments came from submitting a work anonymously shows that it was easier for Le Beau to succeed when her gender was hidden from critics. Despite this and other successes, Le Beau’s struggles to establish connections and to find a supportive environment forced her and her parents to move many times. Le Beau wrote in her memoirs about her family odyssey of leaving Munich’s “intrigues and resentment” for Wiesbaden and Berlin, finally returning home to Baden-Baden in 1893. She felt that her continued rejections from the mostly male musical communities could be blamed on misogyny (Keil 1997, 99). Her story concludes sadly with an impoverished, frustrated, and lonely end (Forkert 2010, 4). Despite these vicissitudes, Le Beau’s Cello Sonata, with its celebratory and tuneful melodies, may receive a resurgence of interest now that it is bound and available for purchase from Hildegard Publishing Company.

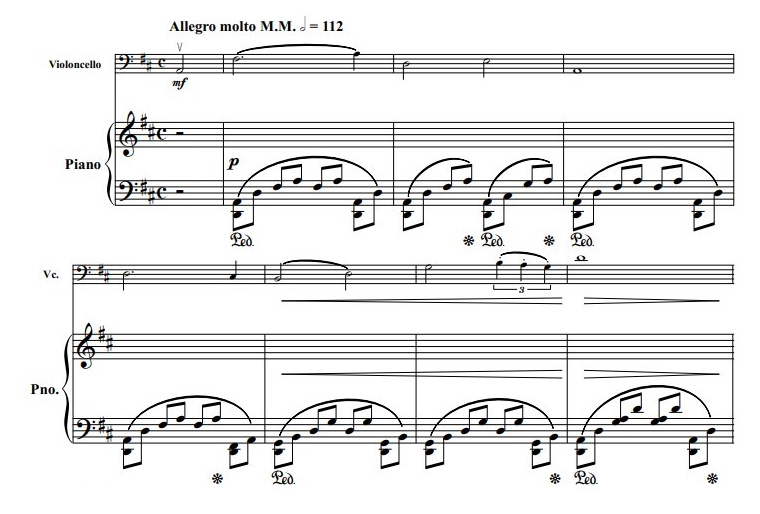

Let us turn now to an analysis of the Cello Sonata. Le Beau begins the first movement in much the same way as her Violin Sonata. Both of their first themes, easily imagined as if set to texts, demonstrate her burgeoning gifts for opera (see Examples 1 and 2).

Example 1. Le Beau, Cello Sonata in D Major, I. Allegro molto, mm. 1–7

Example 2. Le Beau, Violin Sonata in C Minor, I. Allegro, mm. 1–6

The string instrument introduces the theme and then switches roles, handing it off to the piano and then taking up the eighth-note accompaniment. In both sonatas, the truncated phrasing in the opening (8-8-8-4) helps to create momentum. In the cello work, the first melody has seven four-measure units. Rather than rounding off the melody with an eighth unit, Le Beau cadences on a structural elision as the melody transfers to the piano. The second theme begins in the cello on the dominant and features another voice-like utterance of an appoggiatura and a falling fifth. The development is in F major and descends through a circle-of-fifths progression. Le Beau ushers in the recapitulation via an eight-measure phrase on the dominant of D major, and underneath the eighth notes of the cello, she presents the second theme, simplified, in the piano. Her coda features the first theme in a brief canon between the cello and the piano’s right hand. Le Beau understood how to write for the cello. The frequent long tones, choice of key, and comfortable range resonate well and feel pleasant to play. The second movement is an exquisite dirge in B minor, a deeply melancholic piece that possibly reflects study of slow cello and piano writing by Beethoven and Mendelssohn. Le Beau’s cello writing again invites vocal comparisons in this exquisite song-form movement.

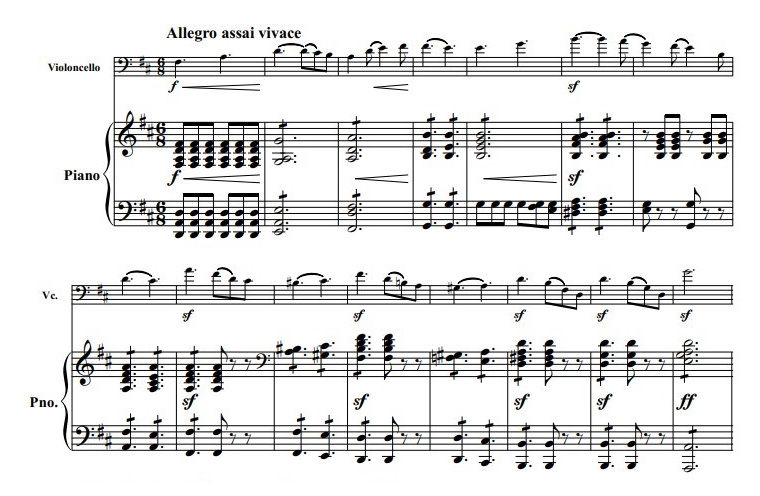

The final movement contains several elements from Mendelssohn’s Sonata no. 2 in D Major, written a few decades earlier in 1843. Ten years before writing her Cello Sonata, Le Beau performed Mendelssohn’s Piano Concerto No. 1 in G Minor, op. 25 with the Baden Court Orchestra. Her compositional style may have been guided by this early exposure to Mendelssohn’s music. With so many similarities between the two cello sonatas, it appears that Le Beau is responding to the earlier work here. Mendelssohn marks his first movement Allegro assai vivace and sets it in 6/8 time. Her final movement, marked Allegro vivace and also in 6/8, begins with the same three notes as his first movement: F♯-A-D. Shortly after, the F♯-E appoggiatura from Mendelssohn’s fourth measure appears in her third measure.

Example 3. Mendelssohn, Cello Sonata in D Major, I. Allegro assai vivace, mm. 1–15

Example 4. Le Beau, Cello Sonata in D Major, III. Allegro vivace, mm. 1–7

Le Beau may even be offering a subtle homage to Mendelssohn’s love for Bach fugues. Two imitative episodes occur in the middle of both second themes, a threading of two and four-measure groupings of eighth notes that flow between the lines of the cello and the two hands of the piano. Le Beau has managed to find good solutions for a crucial element in all cello and piano sonatas—that of balance. In lieu of Mendelssohn’s thick chordal writing, she opts for three- or four-note chords, or simple two-line countermelodies. This kind of fluid and transparent piano writing appears frequently throughout all of her early chamber music works. By placing the cello high enough to sing above the texture, she has produced a more equitable pairing.

In the cello sonata genre, composers have always been challenged by the issue of balance. A good solution can be elusive since the two instruments produce sound differently and project it unequally. As Lewis Lockwood has shown, Beethoven was inscribing the autograph manuscript of his Cello Sonata no. 3 in A Major, op. 69 when it seems that he was beset by doubts regarding balance. He solved the problem by moving voices to different octaves and thinning out the piano chords with canonic entrances (Lockwood 1970, 38–39). Fifty years after Beethoven’s sonata was published in 1809, a famous incident regarding balance between cello and piano is said to have occurred. Brahms and his dedicatee, amateur cellist Josef Gänsbacher (1829–1911), were reading through the composer’s Sonata in E Minor, op. 38 for a salon audience. When the cellist complained that he couldn’t hear himself, Brahms growled, “lucky for you.” (Drinker 1932, 81).

Upon first hearing, one might assume that Ethel Smyth’s Sonata in A Minor is a work by Brahms, albeit with English reserve. Melodic fragmentation, rich counterpoint, and use of the parallel major at final cadences all appear here. Brahms closes the first movement of his E Minor Sonata in the key of E major, and that choice may have influenced Smyth to end all of her movements in the major mode. A beneficial side effect of her thoughtful handling of Brahmsian sonorities is an acute awareness of balance that is evident in the many cautionary dynamic markings. For example, the dominant marking in the first movement, pianissimo, occurs five times as frequently as a forte or fortissimo.

Living and studying in Leipzig where Brahms frequently visited, it is not surprising that Smyth’s sonata would have shown Brahmsian traits. By the age of twenty, Smyth had moved into the house of her teacher, Heinrich von Herzogenberg (1843–1900). Brahms was friendly with her hosts and often sought musical advice from Herzogenberg’s wife, Elisabeth (Bernstein 1986, 308). Since Smyth knew Brahms’s music, it is likely that she studied his Cello Sonata. She writes about a Gewandhaus performance where Brahms conducted his Second Symphony and shares her opinions about his personality (Smyth 1920, 179). In a recording of her opinions that was made when she was past middle age, she states that “I cannot say I liked, or felt happy with him.” She relates amusing and honest portrayals of Brahms’s personality, which she observed while attending the many Brahms-Abende held at the house (Smyth 1927, 1:50). She later published observations of the man and his music in the chapter entitled “Recollections of Brahms,” found in her memoir, Female Pipings in Eden (Smyth 1933, 57–70).

By the time she wrote her Cello Sonata in 1887, Smyth’s friendship with “Lisl” von Herzogenberg had ended. The disruption of nearly a decade of closeness was a calamitous experience for Smyth, akin to losing the love and trust of a parent. Still wounded from the loss of Lisl, and worried that her friends would desert her, she describes a touching interaction with Brahms. She had left her dog in the street in order to hear a rehearsal of his Piano Quintet. All of sudden, her dog bounded toward her into the room and knocked over the cellist’s stand. Horrified by this faux pas, she was relieved when Brahms erupted into laughter, comparing it to his bar-playing days. She wrote, “During the two bereft winters I spent in Leipzig, anything more markedly kind, fatherly, and delicate than Brahms’s manner to me cannot be imagined; but I had always known that with all his faults, he had a heart of gold” (Smyth 1923, 160).

Since Smyth was a successful promoter of her own music, it is surprising that her Cello Sonata fell into obscurity. The answer may lie partly in a decision she made late in life. Toward the end of her career, Smyth inscribed her complete works for posterity. This list, along with her short descriptions, can be found in the archives of the British Museum. There are several omissions from her early years (Dale 1949, 330). One of the omitted pieces was her Cello Sonata. What caused someone so greatly renowned for her compositions, her suffragist activism, and autobiographical writings to effectively bury her own works? This question bears some scrutiny, especially because of the public’s current eagerness to discover lesser-known works by women and those from underrepresented groups.

As a composer, Smyth’s skills developed more slowly than her male peers, due in large part to her upbringing. She only began formal training in theory and composition at age seventeen. In an 1878 letter to her mother during the Leipzig years, she mentions a demoralizing visit to a publishing house that laid bare her feelings of naïveté. The publisher severely doubted whether he could sell her music, and pointed out that only women with famous surnames, such as Clara Schumann and Fanny Mendelssohn, had been successful in doing that. To be told that her career could not progress without a famous male’s family name must have been dispiriting. Smyth left her music with him in any case, but was so downcast that she forgot to request payment for her work (Smyth 1923, 248).

By middle age, Smyth had mostly stopped writing chamber music and instead focused on larger-scale works. Her output was impressive and well received, despite suffering from hearing loss. She composed orchestral works, six operas, and toward the end of her life, a cantata entitled The Prison. Not only had she achieved fame as an opera composer, but she had also accomplished it as a woman. Perhaps when looking back, Smyth felt that her early works did not represent her mature compositional persona. To stake her claim in the traditionally masculine arena of opera composition, she highlighted her larger works over her first efforts in smaller forms.

When nineteenth-century music critics lauded a woman’s compositions, they often used terms such as “virile” and “masculine.” Although it would be an unusual way of describing music today, this was the highest kind of praise a woman could receive back then. Smyth felt strongly that such gender designations were irrelevant: “Art is bi-sexual, the female element implicit with the male . . .” (Smyth 1933, 47). She was particularly frustrated by the English resistance toward employment for women. In certain circles, she is known today not only for her music but also for her commitment to women’s suffrage. In fact, she was so committed to the cause that in 1910 she gave up composing to focus solely on gaining the vote for women. “The whole English attitude [toward] women in fields of art is ludicrous and uncivilised,” she observed. “There is no sex in art. How you play the violin, paint, or compose is what matters” (Smyth 1921, 242).

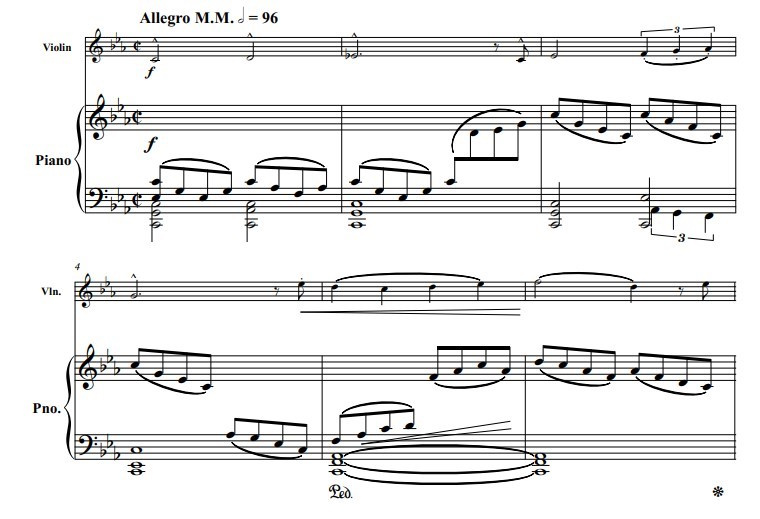

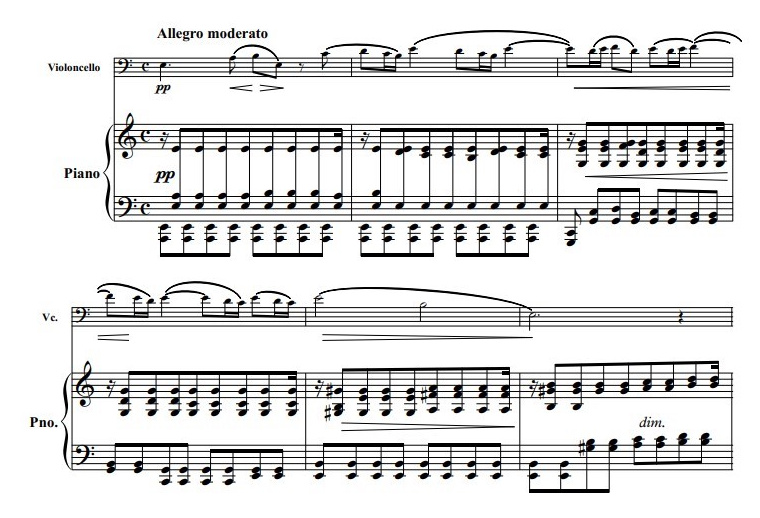

The “virility” that critics noticed in her works might today be described as rhythmic tension, and one hears this from the very start of Smyth’s Cello Sonata. The first theme enters in fragments, gradually outlining a rising scale in A minor. In the piano, low sixteenth-note pulses roil underneath the melody (Example 5).

Example 5. Smyth, Cello Sonata in A Minor, I. Allegro moderato, first theme, mm. 1–6

The Sonata’s second theme is a consoling-like melody with longer note values in the piano. It acts as a foil to the opening melody with its downward motion, falling from the relative major’s tonic.

Example 6. Smyth, Cello Sonata in A Minor, I. Allegro moderato, second theme, mm. 27–31

Here, the falling fifths in the cello are reminiscent of similar material from the closing theme of Brahms’s E Minor Cello Sonata. Like many themes throughout the work, both of these begin pianissimo, despite their contrasting characters. In addition to being emotionally contrasting, the two themes move in different directions: the first theme begins with a rising perfect fourth, and the second one starts with the same interval in descent. Smyth links her themes motivically through a five-note rising or falling scale. Prior to the recapitulation, the cello plays soft drones in fifths and sixths over fragments of the first theme in the piano and then eventually switches roles, taking up the fragments. The movement ends meno mosso, and the drones return, now in A major, evoking a pastoral scene.

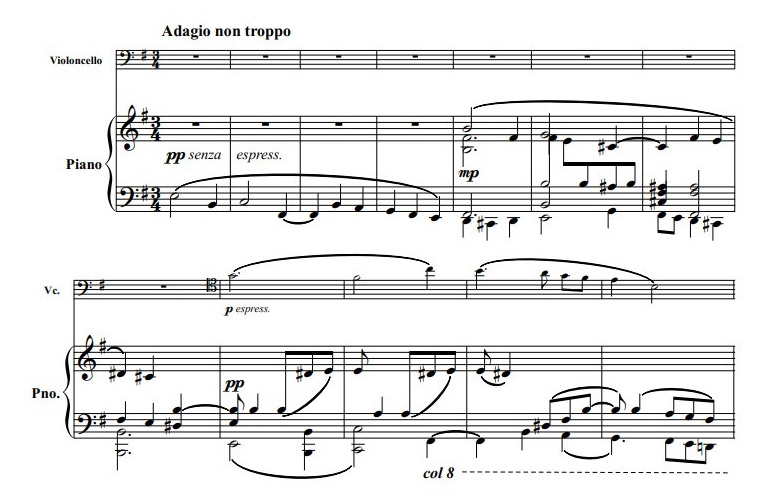

Smyth opens the second movement with a single-note passacaglia in the key of E minor and with simple half notes and quarters depicting a funeral march. We see the descending five-note figure from the first movement in the cello’s first entrance.

Example 7. Smyth, Cello Sonata in A Minor, II. Adagio non troppo, mm. 1–12

The movement’s later sweeping themes and powerful dynamic contrasts present the deepest mourning yet heard in the piece. Smyth brings back the Brahmsian falling fifths in this movement. Initially sounded in m. 58, they function as a route back to the first theme in E minor. When we hear them for a second time in m. 109, half of them have shrunk to augmented fourths. Smyth signals a possibility for hope in the final measures by inverting the fifths in the cello to rising intervals. She ends the movement with an open fifth in the cello and a lone G♯ at the top of an E major chord, voiced low in the piano.

Smyth’s finale, Allegro vivace e grazioso, is a rondo in ABACABA form. We hear the five-note scale motive now in a tarantella on the dominant of A minor. Smyth escalates the tension in this theme twenty-two measures later by shifting from 6/8 to 3/4 meter. The constant running eighth notes and the change in meter contribute to the frenetic expression. The cadenza-like second theme arrives as a welcome change, appearing first in C major and then later in E major. This theme embodies the movement’s original enigmatic marking of grazioso, partly because of the slower tempo and the espressivo designation. Furthermore, the uneven phrase lengths lend a feeling of improvisation and ease that contrasts with the earlier anxiety and drive of the tarantella. The central third theme is an energetic march, suggesting rhythmic and tonal similarities with the finale from Beethoven’s String Quartet, op. 130. In the energetic coda, marked Presto, we hear a decorated version of the tarantella, and in the final phrase, a brief four-measure reminder of the third theme’s march. This insertion, humorous in its new rapid tempo, seems to dash onstage for one more big splash before the piece finally ends.

Countess Dora Pejačević was born in 1885 to a noble family in Našice, Croatia. Although Croatian by birth, she was raised in the German cultural tradition, read works by Rilke and Nietzsche, and studied scores by contemporaries such as Mahler. Unlike Le Beau or Smyth, Pejačević made an impact as a recognized composer in her teenage years. And like these two composers, she did not formally enroll in a conservatory. Her aristocratic parents paid for private instruction rather than allowing her to study with other students. When her family set up residence in the larger city of Zagreb for a time, the proximity to culture offered her many musical opportunities. According to Koraljka Kos (1998), performing groups in major European concert centers like Dresden, Zagreb, and Vienna often showcased Pejačević as the sole living composer, next to older composers like Chopin, Beethoven, and Schumann. Pejačević also experienced misogyny as a composer, despite her achievements. She set the poetry of her friend Karl Kraus to music, and the renowned writer was so delighted that he showed her work to Arnold Schoenberg. Schoenberg praised the songs; however, he added that women should not compose (Kos 1998, 57).

Pejačević ’s Cello Sonata from 1913 appears in the middle of her oeuvre, much of which was chamber music. The German-speaking Pejačević called herself a Wagnerian (Kos 1998, 197), even though chamber music was not a popular genre for late-Romantic German composers. Her Viennese and German heroes—Wagner, Mahler, and Bruckner—wrote nothing for cello and piano. In fact, other than the 1886 Cello Sonata No. 2 in F major by Brahms, the only other canonic German cello sonata from this time was written by a young Richard Strauss in 1883. Although the name of Pejačević might be unknown to US audiences, she is celebrated in her native Croatia. Perhaps her Cello Sonata, as well as her other works, might have been more widely known had she lived longer.

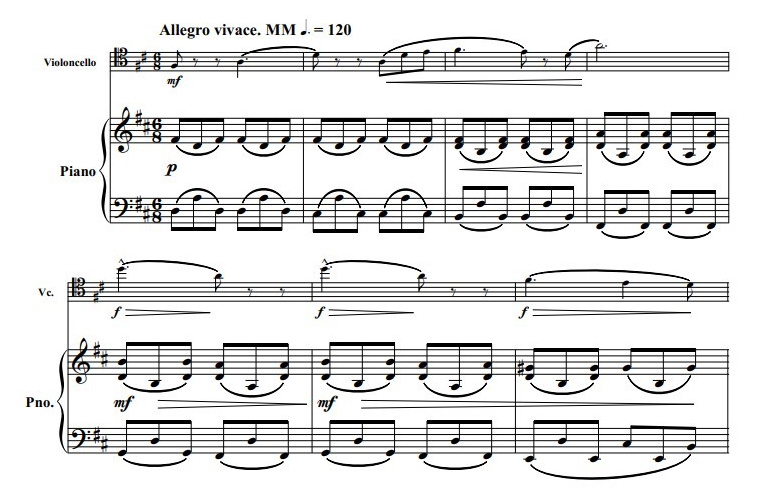

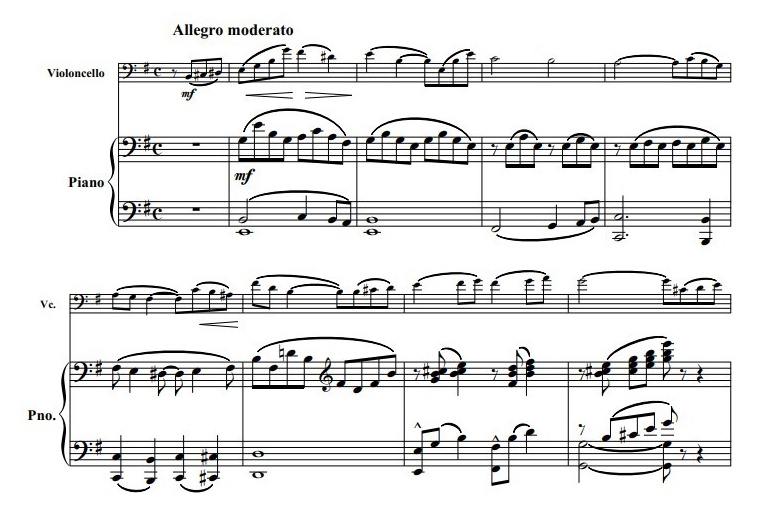

The Cello Sonata in E Minor of Pejačević is a four-movement work of nearly thirty minutes, filled with technical challenges for both cellist and pianist. Its long phrases evolve with a sense of yearning and frustration. The harmonic language, carefully organized motivic connections, and formal structures demonstrate a profound knowledge of contemporary harmony. She builds tension quickly in the first movement, where her E-minor theme moves toward the dominant via harmonies such as B♭7 and E♭7. The first theme is extensive in its range, length, and emotional intensity. The upward sweep of the opening gesture leads to a falling third and a falling fourth. The top notes of these two intervals outline an appoggiatura of an F♯ falling to an E.

Example 8. Pejačević, Cello Sonata in E Minor, I. Allegro moderato, mm. 1–8

Example 9. Pejačević, Cello Sonata in E Minor, I. Allegro moderato, mm. 171–end

The movement ends with the cello wailing on a sustained high E for four measures. Underneath this prolonged misery, the piano descends through IV and VI chords to a final set of determined tonic chords in dense formation.

The energetic second movement is characterized by virtuosic piano arpeggiation and spiccato bow strokes in the cello. This levity is necessary for contrast before we enter into the heart of the Sonata, the third movement’s funeral march. This Adagio sostenuto is in 5/4, an unusual meter that is rarely encountered in cello sonatas up to this point. The appoggiatura from the first movement returns in mm. 16–17, a C falling to a B, and then later, in mm. 45 and 46, it descends even more despondently from a B♭ to an A.

Example 10. Pejačević, Cello Sonata in E Minor, III. Adagio sostenuto, mm. 16–17

This theme recalls the opening of Rachmaninoff’s 3rd Piano Concerto with its similar rhythms and scalar line.

Example 11. Rachmaninoff, Piano Concerto No. 3, I. Allegro ma non tanto, mm. 3–6

Does this similarity, like Le Beau’s quotation, suggest another homage of a woman composer to a more famous male composer? The Russian concerto was written first in 1909; however, it seems impossible that Pejačević could have known it. It had one premiere in New York City, only four years before her sonata was published, and it was not performed for decades afterward. Joseph Yasser has shown that Rachmaninoff, while writing his first theme, may have been influenced by ancient liturgical music (Yasser 1969, 313–28). Although we know that Pejačević was Roman Catholic, it is intriguing to consider the possibility of her hearing Vespers in an Orthodox Church. The Finale of the Cello Sonata begins buoyantly in the key of E major. The third movement’s appoggiatura of C to B reappears here after the recapitulation in mm. 174 and 175. Pejačević ends the entire sonata decisively in E major, tidily using her motive from the beginning, the opening’s appoggiatura. This F♯-E motive, previously wrapped in poignancy, now becomes triumphant in the cello’s confident dotted rhythms.

Before dying in childbirth at the age of thirty-eight, Pejačević wrote a pleading letter of equity to her husband about the life of her future child: “May God grant that our child (if I should leave it to you) be a joy to you—to become an authentically open and great Human Being . . . you should thus behave in the same way whether a boy or a girl is in question; every talent, every genius demands identical concern—gender must not come into question here” (Kos 1998, 171). This private plea to her husband could be broadened into a plea to future music-lovers about the fate of her music.

Conclusion

Women composers have been silenced by misogyny, poverty, and self-doubt throughout the centuries, and society has nothing to gain by continuing to neglect their work. Within the confines of Europe’s restrictions, Luise Adolpha Le Beau, Ethel Smyth, and Dora Pejačević worked hard to bring their musical ideas to life. Though their music may have once been cast aside through either self-doubt or neglected by performers after their death, their pieces can be easily revisited now that they are globally available. Arguments currently rage about whether or not to even keep the canon that has been understood to mean a collection of compositions by men. However, performers and teachers need these compilations for handy reference. It is past time to change our thinking and expand the narrow literature for cello and piano to all genders.

References

Bernstein, Jane. 1986. “‘Shout, Shout, Up with Your Song!’ Dame Ethel Smyth and the Changing Role of the British Woman Composer.” In Women Making Music: The Western Art Tradition, 1150–1950, edited by Jane Bowers and Judith Tick, 304–24. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Dale, Kathleen. 1949. “Ethel Smyth’s Prentice Work.” Music & Letters 30, no. 4 (October): 329–36.

“Dr. Ethel Smyth.” 1912. Musical Times 53, no. 828 (February 1): 81–83. London: Musical Times Publication, ltd.

Drinker, Henry S. 1932. The Chamber Music of Johannes Brahms. Westport: Greenwood Press.

Forkert, Annika. 2010. “Luise Adolpha Le Beau.” Musik und Gender im Internet. (April 14,2010): 1–7. Accessed August 30, 2021. https://mugi.hfmt-hamburg.de/

Keil, Ulrike Brigitte. 1997. “Das Hirtenmädchen Hadumoth: Ein Oratorium nach Szenen aus Joseph Viktor von Scheffels »Ekkehard«, komponiert von Luise Adolpha Le Beau.” In Musik in Baden-Württemberg, vol. 4, edited by G. Günther and R. Nägele, pp. 99–115. Stuttgart: J. B. Metzler.

Kos, Koraljka. 2008. Dora Pejačević. Zagreb: Muzički informativni centar Koncertne direkcije Zagreb.

Le Beau, Luise Adolpha. 2009. Sonate, op. 17. Worcester, MA: Hildegard Publishing Co.

Lockwood, Lewis. 1970. “On Beethoven’s Sketches and Autographs.” Acta Musicologica 42, Fasc. 1/2 (September): 3247.

Mendelssohn, Felix. 2001. Compositions, op. 17, 45, 58, 109. Frankfurt: C.F. Peters.

Olson, Judith. 1986. “Luise Adolpha Le Beau: Composer in Late Nineteenth-Century Germany.” In Women Making Music: The Western Art Tradition, 1150–1950, edited by Jane Bowers and Judith Tick, 282–303. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Pejačević, Dora. 2015. Sonata za violončelo i glasovir u e-molu op. 35. Zagreb: Muzički informativni centar Koncertne direkcije Zagreb.

Rachmaninoff, Sergei. 1910. Concerto No. 3, op. 30. Moscow: A. Gutheil.

Smyth, Ethel. 1887. Sonata in A Minor, op. 5. Leipzig: C. F. Peters.

———. 1921. Streaks of Life. London: Longmans, Green, and Co.

———. 1923. Impressions That Remained: Memoirs. Vol. 1I. London: Longmans Green, and Co.

———. 1933. Female Pipings in Eden. London: Peter Davies.

———. 1987. Memoirs of Ethel Smyth. New York: Viking.

———. [ca. 1930s] “Recollections of Johannes Brahms.” YouTube video. Accessed August 31, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8zbCRjA9wJ8

Yasser, Joseph. 1969. “The Opening Theme to Rachmaninoff’s Third Piano Concerto and itsLiturgical Prototype.” The Musical Quarterly, 55, no. 3 (July): 313–28.

Zigler, Amy Elizabeth. 2009. “Selected Chamber Works of Dame Ethel Smyth.” PhD diss., University of Florida.