Abstract

College and university music students and faculty are faced with an overwhelming amount of information that can help or hinder their personal wellness. The purpose of this qualitative content analysis was to examine wellness resources for students and faculty located on school of music websites at institutions accredited by the National Association for Schools of Music (NASM). I randomly selected 25% of the 645 NASM-accredited institutions (N=161) and analyzed school of music websites using deductive codes derived from the 2019-2020 NASM Handbook’s suggestions regarding health and wellness. Coding revealed a variety of physical health educational techniques and resources, but a lack of mental health education and customized supports. Based on the findings from this content analysis, I offer recommendations for improving school of music websites and discuss the importance of personal and professional wellness resources for faculty and musician-specific mental health resources.

James A. Grymes

Wellness is an active, holistic, and multidimensional process of self-awareness combined with the balance and integration of healthy choices within one’s particular environment (Goss et al., 2010; Rachele et al., 2013). Dimensions of wellness include occupational wellness, physical wellness, social wellness, intellectual wellness, spiritual wellness, and emotional wellness (Hettler, 1976). Due to the rise of chronic disease, mental illness, and negative lifestyle choices in the United States, Amaya et al. (2019) insisted that colleges and universities must create a culture of wellness. Student interaction with the interdependent categories of wellness can lead to growth and development in aspects of living including intellectual and emotional balance, and healthy life skills like exercise, nutrition, and stress management (Anderson, 2016).

Review of selected literature

Within collegiate departments, schools, or colleges of music (hereinafter “schools of music”), music students balance heavy course loads with physically and mentally demanding rehearsals, performances, and practice, which can lead to stress, depression, and anxiety (Kuebel, 2019). These demands on students, in addition to a pressure to excel, can lead to limited physical activity, low levels of physical and psychological health, and poor sleep quality (Araujo et al., 2017). Music education wellness scholars have offered a variety of prevention and protection techniques. For example, meditative practice may help reduce performance anxiety (Diaz, 2018), self-care plans may improve mental health literacy (Keubel, 2019), and injury prevention guides may protect music educators and their students (Taylor, 2016). In order to prevent musician occupational injuries and engage with health care resources, the Performing Arts Medical Association collaborated with the University of North Texas to produce Health Promotion in Schools of Music (Chesky et al., 2006; Palac, 2008). They recommended that all schools of music adopt a health promotion framework, offer an undergraduate occupational health course for all majors, educate students about hearing loss during ensemble instruction, and assist students through active engagement with health care resources.

The National Association of Schools of Music (NASM; 2020) provided in-depth standards of health and safety in the 2019-2020 Handbook. Health and safety standards dictate that students and faculty “must be provided basic information about the maintenance of health and safety within the contexts of practice, performance, teaching, and listening” including the general topics of hearing, vocal, and musculoskeletal health and injury prevention (p. 67). Institutions seeking accreditation must provide student services including effective orientation programs related to study and well-being; education, counselling, and professional physical and mental health care; and counselling for personal, social, vocational, and financial health issues.

One way in which post-secondary schools of music communicate health and safety values and resources to their student population is through their websites. Taddeo and Barnes (2014) position the school website as an environment that aligns with school goals to communicate and innovate, while engaging with students and communities through the exchange of information, ideas, and resources. Many college students have developed a habit of being almost permanently online and connected with others, especially through the use of their smartphones (Vorderer et al., 2016). Constant internet connection may allow students confidential and convenient access to health and wellness services (Mou et al., 2017). College student focus group participants reported substantial engagement with online health information sources, which led Prybutok and Ryan (2015) to claim that internet resources effectively communicate health education, prevention, and management techniques to college students.

Music education and education researchers interested in wellness for college students have documented student attitudes and perceptions (Amaya et al., 2019; Arauju et al., 2017), suggested strategies for approaching stress, burnout, and anxiety (Diaz, 2018; Varona, 2018), and examined the usefulness of health and wellness interventions on students and teachers (Embse et al., 2019; Spahn et al., 2017). Additionally, music scholars have examined wellness topics such as musician hearing, vocal, musculoskeletal, and emotional health (e.g., Conable, 2000; Edgar, 2017; Rosset i Llobet & Odam, 2007; Taylor, 2016) and music education researchers have examined music teacher emotional wellness issues such as stress and burnout (e.g., Bernhard, 2016; Hedden, 2006; Shaw, 2016). However, we know little about the practical, everyday resources with which students and teachers interact, such as those provided online by their educational institutions. Therefore, the purpose of this qualitative content analysis (Selvi, 2020) was to examine wellness resources available online for students and staff at websites for schools of music at NASM-accredited institutions. Research questions included: (1) What wellness content is available on websites for NASM-accredited schools of music? (2) How well does this content align with/satisfy the NASM requirements regarding health and wellness?

Method

Researcher Lens

My fascination with wellness education for music educators and students began during my master’s program when I took a course focused on musicians’ wellness. Throughout the course, I found myself asking why I never had interacted with, or even had thought to consider, the many issues of musicians’ health and wellness. For the past five years, I have sought to infuse elements of physical, mental, and emotional wellness into any interaction with student musicians and music educators, primarily through elements of mindfulness, meditation, and yoga practices. Consequently, my motivation to spread the knowledge of musicians’ wellness likely affected my lens during data collection and analysis.

Design

I used a qualitative content analysis design, which aims to provide a comprehensive and nuanced description of data through analysis of meaning and relationships present in “various forms of human activity and communications” (Selvi, 2020, p. 440). Froehlich and Frierson-Campbell (2013) explained that music education researchers who have used a qualitative approach to content analysis have traditionally asked “who says what to whom, why, and with what effect?” (p. 261). Through this research, I sought to gain insight into what resources schools of music promote, to whom they direct their resources, why they shared wellness resources, and what (if any) results of wellness initiatives they share.

My unit of analysis was the school of music website that accredited institutions provided NASM for their online directory. I believe this unit of analysis is appropriate because the school website is often the first point of reference for students, faculty, staff, and prospective students and their families (Subandi et al., 2019), and often communicates department-, school-, or college-wide held values (Taddeo & Barnes, 2014). Additionally, NASM’s 2019-2020 Handbook required that published materials, including internet websites, which concern an institution “shall be clear, accurate, and readily available” (p. 72).

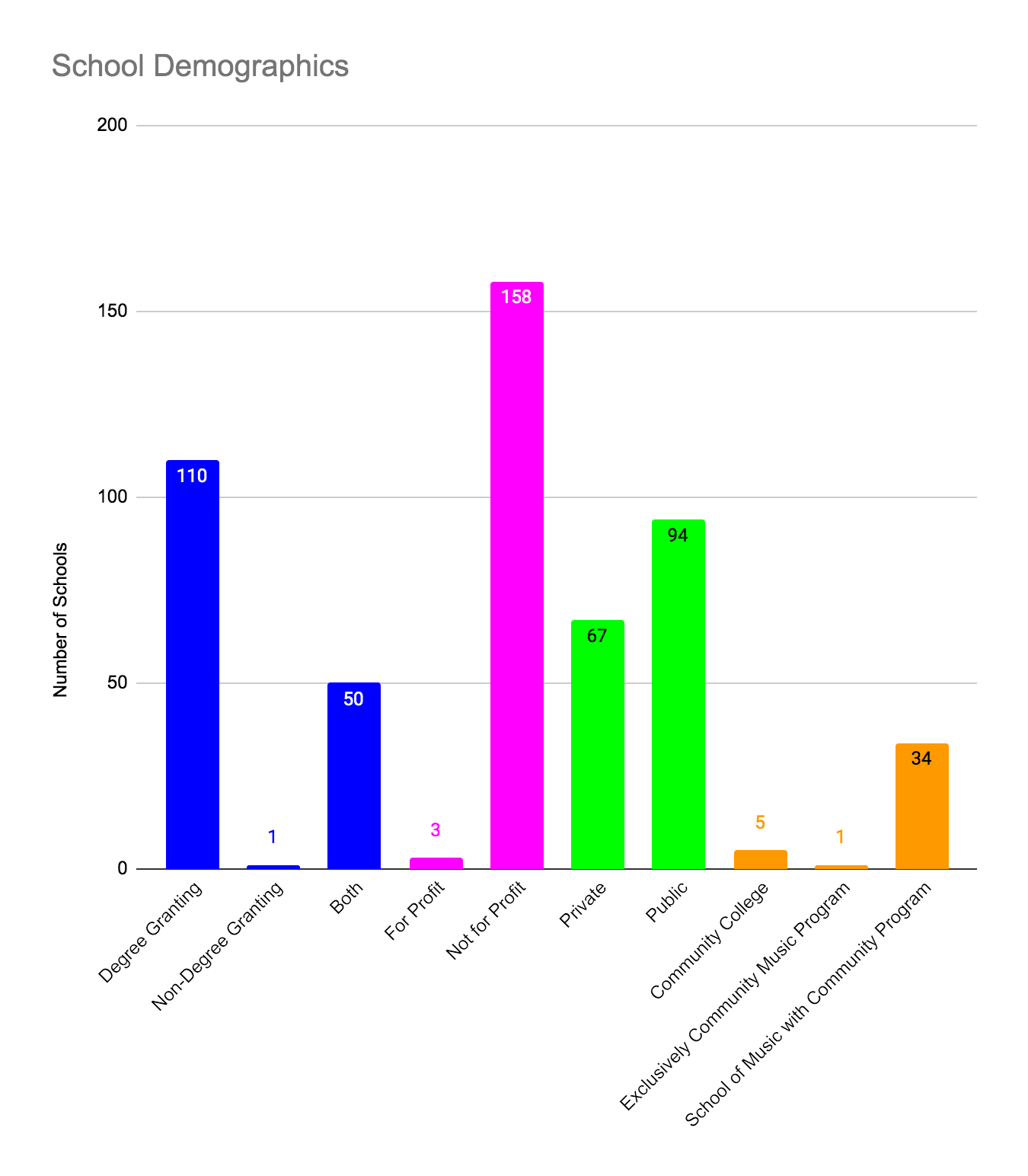

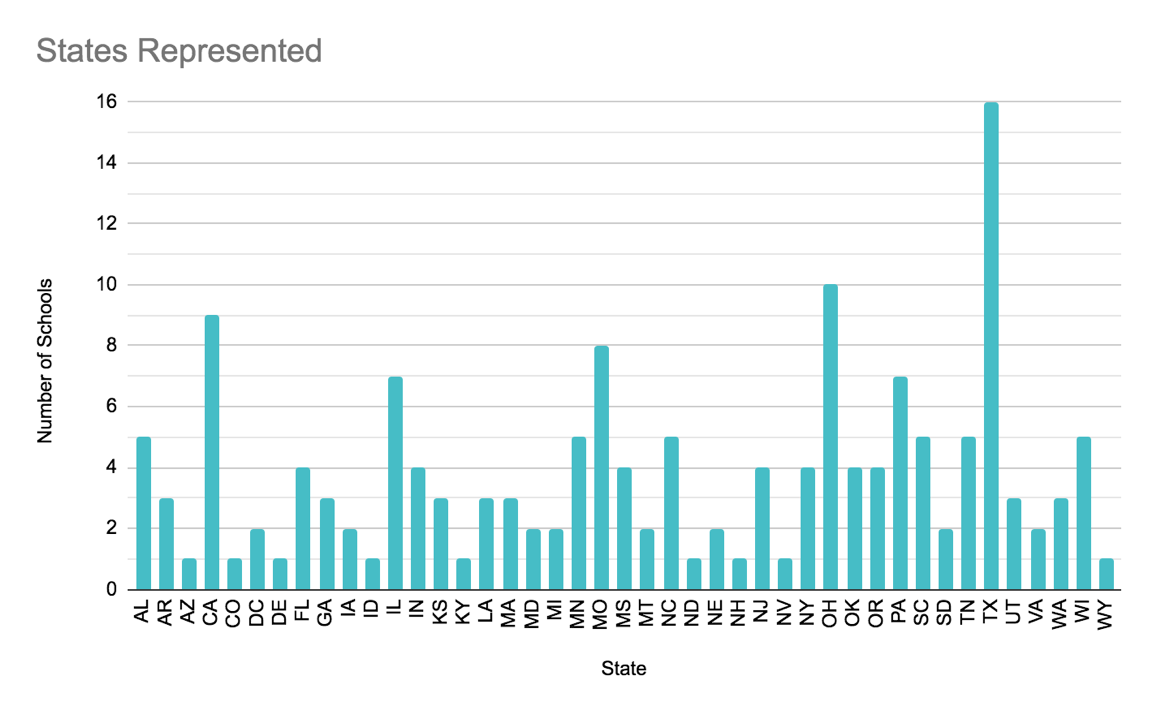

Sample

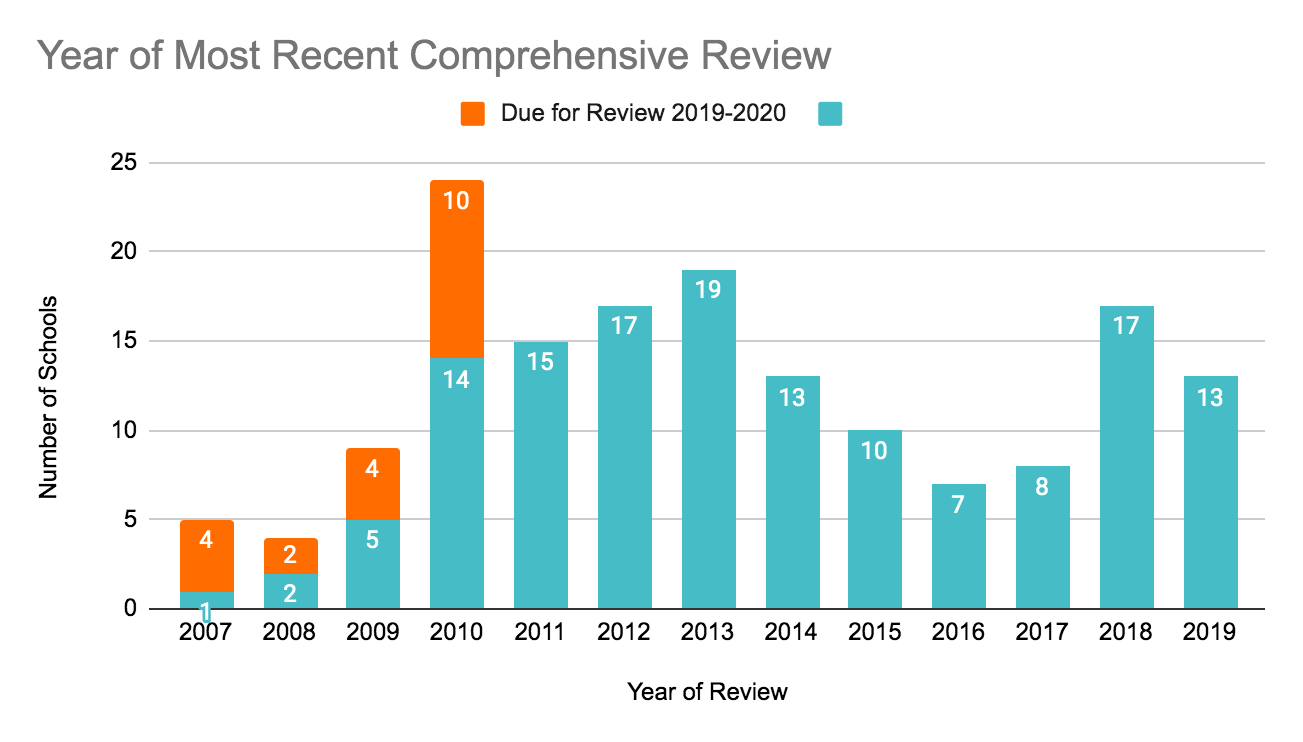

In April of 2020, the NASM online directory identified 645 accredited institutional members, which included degree-granting institutions, community colleges, non-degree-granting schools, and community and precollegiate programs. To complete a random sample of one quarter of the websites provided, I randomized the alphabetical list of NASM institutional members and used a random number generator from stattrek.com to choose 161 random numbers from one to 645 with no duplicates. Because I had access to school names and sampled their websites directly, this was a single stage sampling design (Creswell, 2014). Guided by my research question, I chose not to stratify by region, state, or institution type. See Online Supplemental Materials Appendix A for descriptive information such as school of music regional affiliation and year of most recent comprehensive review.

Data Collection

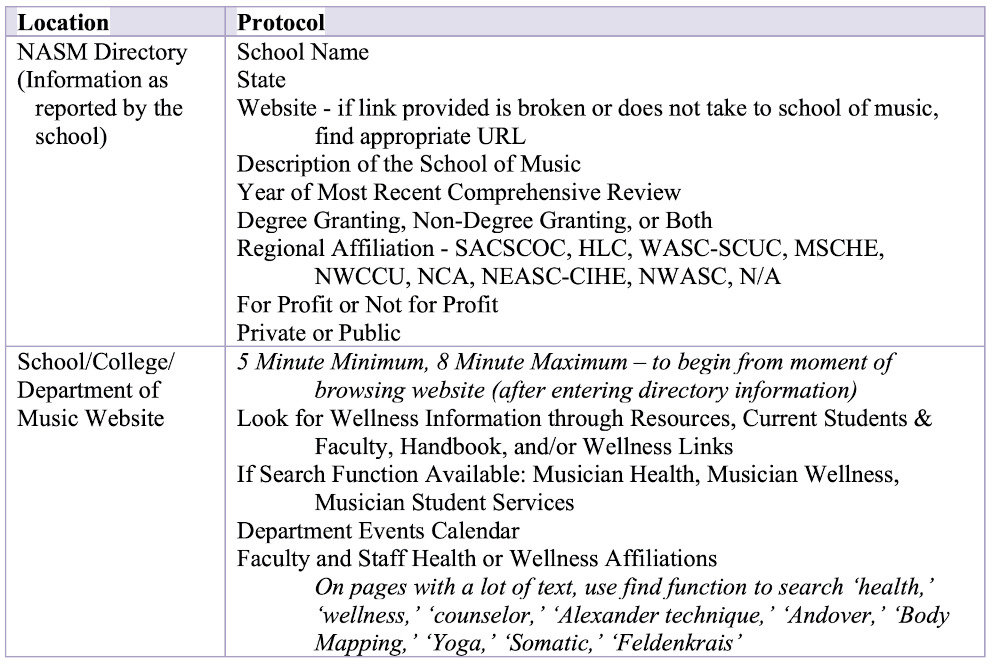

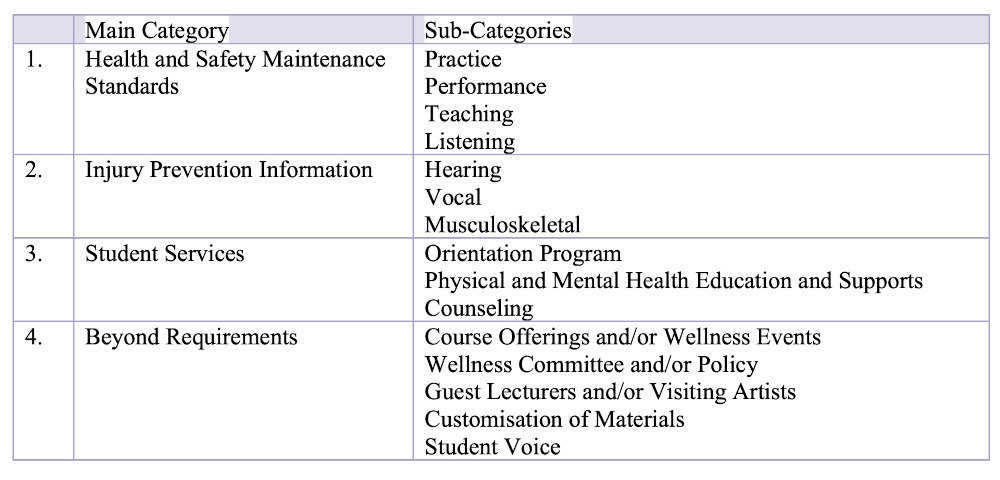

Based on a pilot content analysis of ten institution websites that were not part of the randomly selected sample, I created a data collection protocol (Table 1). Rather than try to locate all possible resources on a site, I instead searched what an average user may find by setting a time limit. Authors from marketing, branding, and analytics fields suggest that website visitors spend an average of two to three minutes on one site before navigating to another (Albright, 2019; Baker, 2017; Spinutech, 2015). With this time frame in mind, I chose to double the average and spend a minimum of five minutes and a maximum of eight minutes on each website. Although this restricted-time data collection approach is not common to qualitative case analysis, it did allow me to acquire “the right amount of data reflecting the full diversity of materials, while minimizing time and energy spent on irrelevant data” (Selvi, 2020, p. 446). I used a deductive approach to coding (Selvi, 2020), creating a guiding list of deductive codes using the 2019-2020 NASM Handbook’s suggestions regarding health and wellness (Table 2). As I examined the data, themes emerged that led me to generate sub-categories of approaches to wellness beyond the NASM standards.

Table 1. Data Collection Protocol.jpg

Table 2. Content Analysis Coding Frame

Data Analysis, Trustworthiness, and Limitations

Once coding was complete, I classified codes into themes, identified patterns, and drew conclusions in response to my research questions. For a qualitative content analysis to be trustworthy, Selvi (2020) argues that researchers must rigorously develop and adhere to a coding frame. In addition to rigorous development of and adherence to a coding frame (Figure 2), sources of trustworthiness in this study included peer review, disclosure of researcher lens and triangulation of the data from multiple and different schools with each other and with the literature. Two limitations of this study are that I sampled only NASM-accredited institutions and that I did not have access to password protected portals on several school of music websites that may have housed additional wellness materials. This lack of access limited my ability to analyze all available materials.

It is important to note the fluid nature of websites. Krippendorff (2019) notes “a content analysis of online text usually represents what has already moved on” (p. 117). I acknowledge that the findings reported below are specific to the websites I sampled at the time of data collection in April of 2020. It is possible that, especially considering the context of COVID-19, schools from this sample have “moved on” and updated their wellness resources since the time of collection. This document, then, serves as a snapshot of the sampled schools’ wellness web presence in April of 2020, at the beginning of the pandemic.

Findings

Available Wellness Content on NASM-accredited School of Music Websites

I randomly sampled 161 (25%) of 645 total NASM-accredited school of music websites. Within the sample, I found information on musician health and safety or wellness for musicians on 61% of the websites that I searched (n = 99). Educational content included NASM advisories, resources created and/or shared by visiting or resident musicians’ wellness experts, and links to websites and online video resources. Wellness supports, while limited, included links to on-campus health and counselling resources, contact information for an on-site expert, and access to prevention tools like musicians’ earplugs.

This sample of NASM-accredited school of music websites relied heavily upon NASM’s advisories on and tool kit resources regarding hearing health, vocal health, and musculoskeletal health and injury prevention. On their website, NASM provides basic information regarding these three types of physical health via documents written for administrators and faculty, faculty and staff, and music students. I found information from or links to one or more of these documents within 64% (n=63) of the websites containing musician health and safety or wellness information. Often these were the only health or wellness resources I could find provided by the school of music on the website.

Other sources of wellness educational content included PowerPoints, PDFs, and Word Documents available for students to download. These resources featured information regarding hearing health, vocal health, and musculoskeletal health and were sometimes provided by a visiting expert in health or musicians’ wellness. For example, the University of Wyoming Department of Music linked a hearing health presentation from an audiology professor, the University of Tennessee at Martin Department of Music attached a basic anatomy for musicians PowerPoint, and several school of music websites included a link to a yoga for performers document created by a voice professor at the University of Mississippi. Some websites included resource pages provided by visiting artists who had discussed wellness topics like the Alexander Technique and dealing with performance anxiety.

Many school of music websites included links to musicians’ wellness websites like Musician’s Health (musicianshealth.com) and Musicians Way (musiciansway.com). These websites provide a wealth of musician-specific approaches to general health and wellness, voice care and health, injury prevention, and medical issues. Other websites linked to specific musician health methods websites like Andover Educators (bodymap.org), The Complete Guide to the Alexander Technique (alexandertechnique.com), and Performing Arts Medicine Association (artsmed.org). A few schools of music linked online video resources for their student musicians. Video resources included health and wellness for musicians training videos, body mapping videos, and informational videos like the American Academy of Audiology’s rap on noise-induced hearing loss. Several schools of music also featured Pilates, yoga, and other workout videos which were not specific to musicians or their education. For a list of resources and links, see Online Supplemental Materials Appendix B.

Content Alignment with NASM Requirements Regarding Health and Wellness

NASM’s 2019-2020 Handbook required schools of music to provide students and faculty basic information about health and safety maintenance as it pertains to practice, performance, teaching, and listening. Topics that must be covered included heath and injury prevention regarding musician hearing, voice, and musculoskeletal issues. Additionally, schools of music must provide the following student services: orientation to topics of well-being; education, counselling, and professional physical and mental health care; and counselling for a wide variety of wellness issues including personal, social, vocational, and financial health. Below, I discuss how the content I found and described above fulfilled each of NASM’s requirements.

Basic Information Provided

Within my timed searches, I found that nearly two-thirds of the school of music websites in the sample included basic information about health and safety maintenance. I often found this information on “Health and Safety” information pages by clicking current student, faculty, or documents and forms navigation tabs. I also found health and safety information within school of music handbooks posted on websites. NASM health and safety documents were the most often linked resources, and many school of music websites did not present information beyond these basics. Although some websites featured clear and obvious health and safety navigation tabs or links on their home pages, much of the health and safety information was difficult to find.

Practice, Performance, Teaching, Listening

Educational ideas and suggestions for students regarding practice, performance, and listening were well documented on school of music websites and within the NASM health and safety documents. Although several schools included the NASM documents for faculty and staff, the majority neglected to provide faculty information regarding health and teaching on their websites that I could easily find within my time limit. Considering that student resources often encourage students to discuss musician health issues with their lesson instructors, ensemble conductors, or class professors, these resources could be important for faculty and staff personally and professionally.

General Topics of Hearing, Vocal, and Musculoskeletal Health

The general topics of hearing, vocal, and musculoskeletal health were present on many school of music websites, in part due to the NASM-provided health and safety documents. Those websites that were more customized and did not rely solely on NASM documents tended to focus mostly on musculoskeletal injury prevention and treatment, citing specific methods like Feldenkrais, the Alexander Technique, and Body Mapping (Andover). Vocal health information was often directed to vocalists in opera and choir programs, while hearing health information was directed to instrumentalists and band and orchestral programs.

Student Services

I had the most difficult time finding information regarding supportive student services within the specified time limit. Websites consistently provided education without musician-specific or school-specific resources to support students or faculty. Similarly, many websites contained a multitude of links with no explanation as to why those links were provided or how they may support students and faculty.

Of the 161 websites I examined, I only found evidence of musicians’ wellness being addressed through an orientation program at four schools of music. Several school websites addressed education, counselling, and professional physical and mental health care. For example, one university provided on-site physical therapy drop-in sessions once a week, on-site hearing tests, ice packs at the conservatory office, weekly yoga classes, and biofeedback facilities. They also encouraged stress and time management through mindful choices and offered links to on-campus counselling and health services. Another website specifically acknowledged “the mental and physical demands that can be involved in the study and practice of music, which might contribute to a greater risk or higher levels of stress, anxiety, depression, etc.” (College of Wooster, “Physical and Mental Wellness” section, 2020) and offered phone numbers for and explanations of their student life office, health and wellness services, and fitness center.

Fulfilling NASM’s requirement of including counselling for personal, social, vocational, and financial health issues, 24 of the school websites included phone numbers for or links to websites for on-campus counselling services. A few school of music websites alluded to on-site academic counselors and support resources. Additionally, several school websites described special musician-specific wellness events that promote stress relief. For example, the University of Michigan School of Music, Theatre, and Dance hosts a stress-relieving event the week before finals which includes therapy dogs, snacks, meditations, and crafts.

Wellness Content Beyond NASM Requirements

Within my timed searches, I found that 36 school of music websites included wellness content that exceeded NASM requirements and/or suggestions. Although these websites represented only 22% of the sample, they contained a wealth of resources which I grouped by themes below. Emergent themes included course offerings, committees and explicitly stated wellness policies, guest lectures and visiting artists, the customization of materials, and the presence of student voice on school of music websites.

Course Offerings and Faculty Experts

Ten school of music websites included descriptions of wellness courses offered through the school of music. Musicians’ wellness courses address issues of both physical and mental health as they pertain specifically to musicians. Four schools of music provide general musicians’ wellness courses, while other schools feature courses that address specific areas of wellness like movement, technique, and mindfulness. See Online Supplemental Materials Appendix C for a full list of course offerings and descriptions.

My examination of school of music faculty pages revealed a variety of wellness-related faculty research and teaching interests. Some faculty expressed a more general interest in wellness for the performing artist, injury prevention for musicians, or teaching healthy musicianship. Other faculty specified particular areas of interest within wellness, including wellness approaches like the Alexander Technique, somatic practice, social-emotional learning, mindfulness-based pedagogy, body mapping, vocology, and hearing health. Although many schools had health and/or wellness experts on faculty, none of these faculty members were linked to the health and wellness page and associations were not explicitly stated for website patrons.

Wellness Committees and Policies

As found on their websites, five schools of music in the sample designated someone or a team of people as representative of their wellness goals. Teams and wellness representatives as described on school of music websites included specialists from within the fields of music, wellness, and medicine. For thorough descriptions of these committees and representatives, see Online Supplemental Materials Appendix D.

Many school of music websites included policies or health and safety statements on their health and safety pages or within their school of music handbook. Common themes within the policies included a statement of commitment to student health and wellness; an explanation of how musicians use their bodies and why they need to be healthy; a reference to the importance of the information in the NASM documents or similar resources; wellness goals of the school and faculty for their students; and encouragement to readers to seek professional advice about specific concerns regarding health or wellbeing. Those schools without policies or statements tended simply to link materials such as PDFs and websites with no reference to why they were there and how they could be helpful. Policies and statements like the ones listed in Online Supplemental Materials Appendix E provide context for wellness resources and publicly acknowledge the importance of musicians’ health initiatives.

Guest Lecturers and Visiting Artists

Several schools of music featured guest lectures and visiting artists who specialize in wellness methods for musicians. Through my searches, I found lecture, workshop, and residency topics including optimising performance, Alexander Technique, avoiding performance-related injury, health and fitness for musicians, and overcoming performance nerves. These lectures and workshops were held throughout the school day and were open to all school of music students.

Customized Materials

Although many schools of music simply copied and pasted generic NASM guidelines to their website, some schools customized their website wellness materials and resources and included information specific to their institution. Through the inclusion of in-building resources like ear plugs and ice packs; on-campus resources like psychology and health services, counseling centers, and student care networks; and community resources like crisis hotlines, massage therapists, and local yoga studios, some schools of music were able to create a one-stop wellness resource center for their students and legitimize student health and wellness concerns and interests. Websites including a statement of importance and explanation of their investment in wellness felt more trustworthy to me as a reader than did those who linked documents with no introduction or clarification of intent.

Student Voice

The Conservatory at Lawrence University notably customized their wellness information webpage by including student voice. Through student stories of experience and short quotes of wisdom, the page shares lessons about listening and responding to your body’s practice and performance fatigue and pain. Students provided advice on dealing with injuries and creating a fitness and wellness routine. This use of student voice localized wellness within the school’s community and legitimized preventative techniques and attitudes for student musicians.

Considerations and Recommendations

A school of music’s website is a powerful tool for facilitating communication, engaging students, faculty, and community members, providing relevant education, and illuminating in-building, on-campus, and community-wide supports. Schools of music from this sample displayed a wide range of approaches to sharing health and wellness information – from simply linking documents to designating musicians’ wellness experts, customising educational materials, and providing on-site wellness support. Recommendations resulting from this study include examining of wellness page elements, the importance of NASM documents, and the call for future research and development of faculty resources and mental health resources.

Wellness Page Elements

Staying “fresh” is one guiding principle for campus wellness efforts according to Rose (2017, p. 227). He suggested constantly updating sites with articles and book reviews, inviting guest speakers, and providing constant connection can invigorate campus connections and support. For sustainability and resourcefulness, Rose recommended rotating leadership and consistently including new voices. Schools of music can use faculty, student, and community expertise to keep their musicians’ wellness efforts fresh and conversations active.

The findings from this study illustrate the possibilities for multi-modal educational outreach and materials on school of music websites regarding musician health and wellness. Roswell (2013) described modes as units of representation such as words, images, animations, video games, film, audio, and movement. Overwhelmingly, the resources provided by the school of music websites that I examined utilized limited modes of education regarding musician wellness, most of which were text driven (e.g., .pdfs, Word documents). Students in higher education are increasingly equipped to navigate through a variety of modes and have come to expect multimodal communication from in-person and media-based education (Breuer & Archer, 2016). Lewis (2020) challenged music educators to acknowledge that many of the profession’s go-to pedagogies are incompatible with current students’ learning and encouraged university educators to embrace their students’ digital assets and lived experiences. School of music websites like those I examined are an excellent space to provide students with multiple modes of original or borrowed wellness resources, including popular modes like videos, podcasts, infographics, and interactive discussion boards.

The most impactful websites in regard to communicating wellness standards and expectations included elements of customisation, explanation of importance, and links to resources representing a variety of modes of communication and methods of approaching wellness. The least impactful websites linked wellness resources with no explanation, used large blocks of text with no breaks for the eye, and included no resources specific to the school or community. Following my analysis, I suggest those music school leaders including wellness resources on their school of music website be sure to include a wellness policy, explicitly state faculty wellness interests and expertise, and provide building-, campus-, and community-specific resources that distinguish your musicians’ wellness program from all the others.

NASM-Provided Resources

Schools of music within this sample relied heavily on NASM-generated hearing, vocal, and musculoskeletal health resources to fulfil their health and safety requirements. These resources are thorough, well-constructed, and easy to read and can be customized for any school. However, because these documents must be downloaded and linked as PDFs, schools of music may upload them the year of their accreditation renewal and not return to them for another 10 years. These materials can easily fall out of date, links can be broken, and websites can be discontinued. Perhaps NASM could assist by reconsidering their mode of communication, and updating to a webinar, podcast, or video communication style and/or a website that is consistently updated.

Faculty Considerations

On most of the school of music websites, I was unable to easily find faculty who were interested in music wellness research and/or practices. Faculty web pages in general were difficult to navigate and did not share faculty research interests or course information. Most faculty pages simply listed instrument or teaching specialty and required a reader to go to a separate biography page for each individual faculty member. Many times, I only clicked on names because I knew them from the music education wellness community, and no health and safety pages listed wellness-specific faculty. Some faculty pages did not include biographies or teaching information, and some sites did not list faculty at all. Next to the peer group, Astin (1993) reported, “the faculty represents the most significant aspect of the student’s undergraduate development” (p. 410). Insufficient faculty information is a lost opportunity for future students to know who they might study with and what they could learn from them and for current students to find who they might approach with wellness-specific questions.

Schools of music should include resources for faculty on their webpages if they expect their faculty to be the first responders to music student performance-related physical injury and mental health issues. If educators are to “become substantially involved in injury prevention by teaching health-conscious music-related practices to students” (NAfME, 2007, “The Music Educator’s Role” section) as suggested by the National Association for Music Education Health in Music Education position statement, they need resources that help them learn to reduce performance injury and encourage healthy habits of auditory, physical, and emotional health. Pierce (2012) classifies wellness training as an integral part of music educators’ education, “not only so they may pass it on to their students but also for their own well-being” (p. 163).

Mental Health Resources

Information and resources regarding mental health were notably lacking, particularly those that were musician specific. For college students, mental health issues can impact everything from academic struggles, social difficulties, and self-care practices, to extreme behaviours, intolerance to stress, and struggles with emotional regulation (Hutchinson, 2017). As several school of music sites noted, student musicians experience a special set of mental health needs including performance anxiety, exhaustion, stress, and burnout. Music students have reported experiencing mild to extreme anxiety, brought about by factors such as work overload, academic and musical stressors, and/or a lack of sleep (Koops & Kuebel, 2019). Recently, students have additionally experienced the trauma of a global pandemic, which has led scholars like Edgar and Morrison (2020) to call for increased social and emotional resources for student musicians. Future research and development by NASM and music wellness researchers should focus on creating mental health resources as strong, useful, and easy to find as those we currently have for vocal, hearing, and musculoskeletal health. As evidenced by the wide-spread use of NASM’s physical health documents, a NASM-generated mental wellness document would have great impact within the NASM-accredited school community.

Conclusions

Musicians’ wellness is an important and increasingly prominent topic in the field of music education. This content analysis illuminated the wealth of practical, everyday wellness resources available for music students and teachers in higher education, but also the uneven and inconsistent quality of and distribution of those resources via school of music websites. The suggestions offered above provide ways in which school of music website administrators may effectively share pertinent wellness information with the students and communities they serve and enhance a virtual culture of musicians’ wellness.

References

Albright, D. (2019, July 23). Benchmarking average session duration: What it means and how to improve it. Databox. https://databox.com/average-session-duration-benchmark#definition

Anderson, D. S. (2016). A mandate for higher education. In D. S. Anderson (Ed.), Wellness issues for higher education (pp. 1-15). Routledge.

Amaya, M., Donegan, T., Conner, D., Edwards, J., & Gipson, C. (2019). Creating a culture of wellness: A call to action for higher education, igniting change in academic institutions. Building Healthy Academic Communities Journal, 3(2), 27-40. https://doi.org/10.18061/bhac.v3i2.7117

Araujo, L. S., Wasley, D., Perkins, R., Atkins, L., Redding, E., Ginsborg, J., & Williamon, A. (2017). Fit to perform: An investigation of higher education music students’ perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors toward health. Frontiers in Psychology 8(1558), 1-19. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01558

Astin, A. W. (1993). What matters in college?: Four critical years revisited. Jossey-Bass.

Baker, J. (2017, August 28). Brafton 2017 content marketing benchmark report. Brafton. https://www.brafton.com/blog/strategy/brafton-2017-content-marketing-benchmark-report/

Bernhard, H. C. (2016). Investigating burnout among elementary and secondary school music educators: A replication. Contributions to Music Education, 41, 145-156.

Breuer, E., & Archer, A. (Eds.). (2016). Multimodality in higher education. BRILL.

Chesky, K., Dawson, W. J., & Manchester, R. (2006). Health promotion in schools of music. Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 21, 142-144.

The College of Wooster. (n.d.). Health and safety. Department of Music. Retrieved April 12, 2020, from https://www.wooster.edu/departments/music/health-safety/

Conable, B. (2000). What every musician needs to know about the body: The practical application of body mapping to making music. Andover Press

Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. SAGE Publications.

Diaz, F. M. (2018). Relationships among meditation, perfectionism, mindfulness, and performance anxiety among collegiate music students. Journal of Research in Music Education, 66(2), 150–167. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022429418765447

Edgar, S. N. (2017). Music education and social emotional learning: The heart of teaching music. GIA Publications, Inc.

Edgar, S. N., & Morrison, B. (2020). A vision for Social Emotional Learning and arts education policy. Arts Education Policy Review, 1-6.

Embse, N., Ryan, S. V., Gibbs, T., & Mankin, A. (2019). Teacher stress interventions: A systematic review. Psychology in the Schools, 56, 1328-1329. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22279

Froehlich, H. C., and Frierson-Campbell, C. (2013). Inquiry in music education: Concepts and methods for the beginning researcher. Routledge.

Gonzaga University. (n.d.). Student Learning Outcomes. College of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved April 9, 2020, from https://www.gonzaga.edu/college-of-arts-sciences/departments/music/about-the-department/student-learning-outcomes

Goss, H. B., Cuddihy, T. F., & Michaud-Tomson, L. (2010). Wellness in higher education: A transformative framework for health related disciplines. Asia-Pacific Journal of Health, Sport and Physical Education, 1(2), 29–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/18377122.2010.9730329

Hedden, D. G. (2006). A study of stress and its manifestations among music educators. Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education, (166), 57-67.

Hettler, B. (1976) Six dimensions of wellness model. National Wellness Institute, Inc. https://www.nationalwellness.org/resource/resmgr/pdfs/sixdimensionsfactsheet.pdf

Hutchinson, D. S. Creating and cultivating a campus community that supports mental health. In D. S. Anderson (Ed.), Further wellness issues for higher education (pp. 39-54). Routledge.

Limestone College Fine Arts. (n.d.). Music handbook 2019-2020. Department of Music. Retrieved April 9, 2020, from https://finearts.limestone.edu/music/current-students

National Association for Music Education. (2007). Health in music education. https://nafme.org/about/position-statements/health-in-music-education-position-statement/health-in-music-education/

National Association of Schools of Music. (2020, February 25). Handbook 2019-2020. https://nasm.arts-accredit.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2020/01/M-2019-20-Handbook-02-13-2020.pdf

Koops, L. H., & Kuebel, C. R. (2019). Self-reported mental health and mental illness among university music students in the United States. Research Studies in Music Education. https://doi.org/10.1177/1321103X19863265

Krippendorff, K. (2019) Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology (4th ed.). SAGE Publications.

Kuebel, C. (2019). Health and wellness for in-service and future music teachers: Developing a self-care plan. Music Educators Journal, 105(4), 52–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/0027432119846950

Lewis, J. (2020). How children listen: Multimodality and its implications for K-12 music education and music teacher education. Music Education Research, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/14613808.2020.1781804

Mou, J., Shin, D.-H., & Cohen, J. F. (2017). Tracing college students’ acceptance of online health services. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 33(5), 371–384. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2016.1244941

Palac, J. (2008). Promoting musical health, enhancing musical performance: Wellness for music students. Music Educators Journal, 94(3), 18-22.

Pierce, D. L. 2012. Rising to a new paradigm: Infusing health and wellness into the music curriculum. Philosophy of Music Education Review 20 (2): 154-176. https://doi.org/10.2979/philmusieducrevi.20.2.154.

Prybutok, G., & Ryan, S. (2015). Social Media: The Key to Health Information Access for 18- to 30-Year-Old College Students. CIN: Computers, Informatics, Nursing, 33(4), 132–141. https://doi.org/10.1097/CIN.0000000000000147

Rachele, J. N., Washington, T. L., Cockshaw, W. D., & Brymer, E. (2013). Towards an operational understanding of wellness. Journal of Spirituality, Leadership and Management, 7(1), 3-12. https://doi.org/10.15183/slm2013.07.1112

Rose, T. S. (2017). Organizing wellness issues: Walking together to build bridges for campuses today and communities tomorrow. In D. S. Anderson (Ed.), Further wellness issues for higher education (pp. 221-231). Routledge.

Rosset i Llobet, J. & Odam, G. (2007). The musician’s body: A maintenance manual for peak performance. The Guildhall School of Music & Drama and Ashgate Publishing Limited.

Roswell, J. (2013). Working with multimodality: Rethinking literacy in a digital age. Routledge.

Selvi, A. F. (2020). Qualitative content analysis. In J. McKinley and H. Rose (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of research methods in applied linguistics (pp. 440-452). Routledge. https://doi-org.proxy1.cl.msu.edu/10.4324/9780367824471

Shaw, R. D. (2016). Music teacher stress in the era of accountability. Arts Education Policy Review, 117(2), 104-116. https://doi.org/10.1080/10632913.2015.1005325

Southern Adventist University. (n.d.). Health and safety awareness. School of Music. Retrieved April 11, 2020, from https://www.southern.edu/academics/academic-sites/music/HealthAndSafetystatement.html

Spahn, C., Voltmer, E., Mornell, A., & Nusseck, M. (2017). Health status and preventive health behavior of music students during university education: Merging prior results with new insights from a German multicenter study. Musicae Scientiae, 21(2), 213–229. https://doi.org/10.1177/1029864917698197

Spinutech. (2015, October 13). 7 website analytics that matter most. https://www.spinutech.com/digital-marketing/analytics/analysis/7-website-analytics-that-matter-most/

Subandi, S., Syahidi, A. A., & Asyikin, A. N (2019). Measuring user assessments and expectations: The use of webqual 4.0 method and importance-performance analysis (IPA) to evaluate the quality of school websites. Journal of Information Technology and Computer Science, 4(1), 76. https://doi.org/10.25126/jitecs.20194198

Taddeo, C., & Barnes, A. (2014). The school website: Facilitating communication engagement and learning. British Journal of Educational Technology, 47(2), 16.

Taylor, N. (2016). Teaching healthy musicianship: The music educator's guide to injury prevention and wellness. Oxford University Press.

Varona, D. A. (2018). The Mindful Music Educator: Strategies for Reducing Stress and Increasing Well-Being. Music Educators Journal, 105(2), 64–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/0027432118804035

Vorderer, P., Krömer, N., & Schneider, F. M. (2016). Permanently online – Permanently connected: Explorations into university students’ use of social media and mobile smart devices. Computers in Human Behavior, 63, 694–703. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.05.085

Appendices

School of Music Sample Descriptive Information

State N = 43

Resources Linked by School of Music Websites

|

Resource Type |

Links |

|

National Association for Schools of Music (NASM) and the Performing Arts Medicine Association (PAMA) |

|

|

Websites |

Andover Educators Recommended Reading The Complete Guide to the Alexander Technique |

|

Online Video |

Sample School of Music Course Offerings (Comprehensive)

|

School |

Course Name |

Course Description / Key Words |

|

Willamette University |

Coordinating Movement for Musicians |

This course is designed for students interested in exploring movement as it relates to playing a musical instrument, singing or acting. Students will learn Body Mapping, a method for improving coordination. Participants gain ease in performing, learn how improved coordination enables them to better avoid fatigue, injury and technical limitation, and thereby be able to more completely realize their musical and artistic intentions. |

|

California State University, Fullerton |

TBD, beginning Fall 2020 |

Introduction for all new undergraduate music students into principles of peak performance and musician-focused health and wellness |

|

Eastern Washington University |

Alexander Technique |

Alexander Technique |

|

Indiana University |

Postural Alignment for the Musician |

Biomechanical integration of the muscular and skeletal systems to promote a balanced and supported posture for all musical activities. Centering and relaxation skills. |

|

Mindfulness-Based Teaching and Wellness |

This class is for music students interested in learning about and incorporating mindfulness-based meditation and wellness practices into their work as music teachers and learners. Topics will include the scientific foundations of mindfulness-based practices, along with strategies for incorporating these principles into music teaching and learning. |

|

|

Movement for Singers |

This course will consist of an introduction to techniques and methods of movement specifically designed for singers, incorporating basic yoga postures, mindfulness, basic ballet positions, and improvisatory organic movement. |

|

|

Lawrence University |

Alexander Technique |

Alexander Technique |

|

Southwest Minnesota State University |

Public Performance Studies |

N/A – mentioned on health and safety page: “at least one of these topics [hearing, vocal, musculoskeletal health] is each semester during MUS110.” |

|

The Catholic University of America |

Wellness for Musicians |

A study of the various dimensions of wellness for musicians, including physiological, psychological, pedagogical, and cultural aspects. Affords students the opportunity to reexamine and restructure their music-related work habits and lifestyle consistent with injury prevention and well-being. Offered on a rotational basis. |

|

University of Massachusetts Amherst |

Musician Health and Wellness |

Music Education course |

|

University of Michigan |

Wellness for the Performing Artist |

This class introduces students to wellness topics such as performance anxiety, stress management, vocal health, Yoga, Feldenkrais, and Laban Movement Analysis, with the aim exploring the intersection of physical movement, mental health and performance. Active participation through movement and in-class performance are required. |

|

Alexander Technique Intro |

The goal in this class is to restore the ease and enjoyment of performing by examining habits of tension that can interfere with fluid movement and expanded creativity. Using the self-awareness principles embodied in the Alexander Technique, students learn to restore free and easy breath, let go of unnecessary tension, and reduce self-defeating thoughts that interfere with instinctual freedom. Group and individual instruction provided. |

|

|

Yoga for Performers |

Balancing body, mind, and spirit for optimal performance. Breath-based focus on exercises to increase flexibility, balance, mindfulness, and release of entanglements. |

|

|

University of Nevada, Las Vegas |

The Healthy Musician |

This course gives specific information about practical anatomy and movement. Students will gain ease in performing and learn how improved coordination enables them to avoid fatigue, technical limitation and injury. |

|

Music Wellness |

Focuses on past and current research related to health preservation and injury prevention among musicians. Vocal, auditory, mental and neuromusculoskeletal health will be investigated through the exploration of Body Mapping, as well as methods developed by Feldenkreis, Alexander, Taubman and others. |

School of Music Wellness Committees or Faculty Representatives Examples

|

Duquesne University |

|

This School of Music employs an Ombudsperson for Health and Safety and encouraged those students concerned about health or safety as it related to their lives as musicians contact this person |

|

The Ohio State |

|

This website designated three music program faculty for their wellness program: a musician mind/body wellness specialist, a music auditory heath advocate, and a vocal wellness expert |

|

The University of Michigan School of Music, Theater, and Dance |

|

Wellness team is lead by a wellness initiative program manager who brings together professors and experts from the Audiology Department, Counseling and Psychological Services, Depression Center, MedSport Department and Athletic Training Center, Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Vocal Health Center, and Music Department. This team offers monthly performing arts health clinics for students experiencing performance-related pain |

|

University of Nebraska Lincoln Glenn Korff School of Music |

|

This school of music’s wellness committee advises on matters of health, wellness, and safety and generate and disseminate materials to students, faculty, and staff |

|

University of Nevada, Las Vegas College of Fine Arts |

|

This college’s Consortium for Health and Injury Prevention seeks to empower performing artists with education about health issues and support for injury prevention and recovery |

Example Wellness Policies or Health and Safety Statements

|

University of Texas at Austin |

|

The Butler School of Music cares about the health and wellbeing of its students, faculty, and staff. It is important for individuals to consider how their life choices can impact their health and musical performance. The materials provided below are informational in nature and are intended to provide a broad introduction to the occupational health concerns of musicians. This information is not intended to substitute for the expertise of health care professionals. We encourage all Butler School faculty, staff and students to seek professional advice about specific concerns regarding health or wellbeing |

|

Indiana University |

|

The Jacobs School of Music collaborates with its students, faculty, and staff to create a setting for learning and working that promotes health and wellness. We seek to achieve this by maintaining safe and healthy learning environments that foster a culture focused on open communication about wellness issues. We work with units across the IUB campus, including the Hearing Clinic in the Department of Speech and Hearing Sciences, Counseling and Psychological Services (CAPS), and the School of Public Health, to provide services to meet this goal |

|

Eastern Washington University |

|

Musicians are susceptible to a wide range of injuries due to extended and repetitive use of the body and exposure to high sound levels. They are also susceptible to psychological stress through the demands of the field. Students are urged to familiarize themselves with injury and stress prevention approaches and to implement them as appropriate. Students are encouraged to wear noise reduction devices during rehearsals and performances as appropriate. Students are also encouraged to take advantage of the services available to them from William Conable, a world-renowned teacher of the Alexander Technique who facilitates this course every term. In the case of practicing and performance-related injury, students should seek immediate medical consultation and report conditions to their applied instructors, ensemble directors, and department chair. Any necessary accommodations will be addressed by the chair on a case-by- case basis in consultation with the student and qualified faculty. All safety and building-related health concerns should be reported to the department chair and appropriate staff as soon as concerns are apparent |

|

Bemidji State University |

|

Musicians are athletes, and just like athletes, it is important that they treat their minds and bodies with the utmost care and respect. Whether during enrollment at Bemidji State University or beyond, it is important that all who study here consider the importance of their health and safety in all they do. Just like athletes, musicians need to physically function at a very high level. Misuse of the body that leads to injury can get in the way of this. While some injuries seem minor to most athletes, they can be debilitating to the musician who needs full function of their body to perform or learn correctly. These injuries can come from a variety of activities and are not always obvious. While it is easy to illustrate some activities that have a high risk of injury (rock climbing/bullfighting), it is less obvious and more often that repetitive actions lead to serious injury over time for musicians....It is important to take care in all you do, so that you are healthy and safe to progress towards all goals as a musician. Some activities that may help in your routine include:....While you are in rehearsal, class, or private practice, you should always use safe and healthy guidelines to protect yourself. Be aware of posture and pay attention to the signs of strain on any part of your body. If you have concerns, bring them up to your ensemble director, rehearsal leader, etc. so that they may be addressed. Your concerns may affect everyone else, so don’t be afraid of bringing them up |

|

Snow College Music Department |

|

It is the policy of the Snow College Music Department that all students understand the basic risks to health and safety associated with the study of music. This document contains important information concerning your health and safety as a musician as well as strategies for managing those risks. Please read it carefully and discuss any concerns that might develop with your teachers. Remember, when it comes to issues of health and safety, there is no “rank or tenure.” If you see an unsafe or potentially dangerous situation, please report it immediately to the nearest faculty member or supervisor. We hope that by paying attention to these issues, you will have a long and productive relationship with music |