Abstract

Burnout is high among college/university faculty across disciplines, negatively impacting job performance and increasing costs to institutions. Burnout may be particularly impactful in creative fields such as music where faculty typically maintain vigorous work and performance schedules while meeting myriad job responsibilities. This exploratory study measured burnout in three dimensions—emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal achievement— among 27 music professors at three universities in the Midwestern United States using the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI). Additionally, participants indicated their perceptions of job conditions on a new instrument developed for the purpose, the University Faculty Job Perceptions Inventory (UFJPI). Examination of correlations between MBI burnout dimensions, between categories of items on the UFJPI, and between MBI burnout dimensions and UFJPI categories revealed several significant findings. Strongly positive significant relationships between the emotional exhaustion and depersonalization subscales of the MBI emerged, however no significant relationships were observed between personal accomplishment and either emotional exhaustion or depersonalization. Emotional exhaustion positively correlated with the UFJPI categories of Job Profile & Resources, Time, Fairness & Evaluation, Work Climate, and Student Issues. Depersonalization positively correlated with work perceptions relating to Job Profile & Resources, Time, Work Climate, and Student Issues. Further research using a larger population sample will illuminate which work conditions are most predictive of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal accomplishment scores among university music faculty to illuminate a path toward meaningful institutional interventions.

James A. Grymes

An Exploratory Study of Relationships Between Job Perceptions and University Music Faculty Burnout

Burnout, a long-lasting state usually arising from chronic stress encountered at work, has been described as the biggest occupational hazard of the 21st century (Ahola & Hakanen, 2014) and is estimated to cost the US economy hundreds of billions of dollars per year in sick time, long-term disability, and job turnover. The problem of teacher attrition due to burnout within K-12 education settings is well-established (Dubois & Mistretta, 2020), and studies of burnout among university faculty have revealed comparable burnout rates (Watts & Robertson, 2011). Job stressors cited by numerous studies of university faculty across disciplines in various countries include low salaries; job insecurity; lack of funding, resources, and support services; task overload; poor leadership or management; and a lack of promotion, recognition, and reward opportunities (Byrne, 1999; Dubois & Mistretta, 2020; Kinman & Wray, 2013).

Burnout is not the same condition as depression, though both share core hallmarks of exhaustion and detachment. At least initially, symptoms of burnout are job-related and situational while depression is more pervasive (Schaufeli, 2017). However, burnout or prolonged job stress often spirals into serious depression over time (Ahola & Hakanen, 2014; Schaufeli, 2017). Burnout can alter neural circuits in the brain, specifically resulting in physical changes to the amygdala. These changes have also been associated with decreased cognitive and fine motor functions (Savic, 2013) and diminished executive functioning, attention, and memory (Maslach et al., 2018). Burnout is also strongly correlated with adverse long-term somatic effects, including headaches, sleep disturbances, physical exhaustion (Maslach et al., 2018), heart disease, diabetes, infections, and musculoskeletal pains (Ahola & Hakanen, 2014; Hakanen et al., 2008).

Dimensions of Burnout

Burnout is a syndrome involving three distinct dimensions of feelings. For educators, these dimensions are: (1) emotional exhaustion, (2) depersonalization, and (3) reduced personal accomplishment (Halbesleben & Buckley, 2004; Maslach et al., 2018). Emotional exhaustion arises as the faculty member’s energy and professional enthusiasm drains away, leaving less capacity to engage with students. Depersonalization refers to an unfeeling or impersonal response to students. When this dimension is high, educators no longer have positive feelings toward students and may demonstrate indifference or negativity by using derogatory labels or generalizations, exhibiting distant or cold attitudes, or distancing themselves from students.

Personal accomplishment refers to feelings of competence and achievement in teaching. A personal accomplishment crisis can be severe and enduring for educators (Maslach et al., 2018). Most educators enter teaching to help students learn and grow, and when they no longer feel they are effective in doing so, they tend to become profoundly disappointed. Successful college music teaching requires high energy and professional enthusiasm to maintain effective teaching while productively meeting a myriad of additional responsibilities. Burnout is therefore likely to negatively impact the quality of instruction and job performance (Hamann et al., 1988). Unfortunately, the negative slide to burnout often starts from a position of strength and success. It is often the most highly driven and engaged professionals who are most susceptible to burnout over time (Maslach & Leiter, 1997).

In addition to strong negative impacts for individuals, burnout imposes high costs to the organizations that employ them. Financial impacts to institutions include high job turnover, absenteeism, and lowered productivity. Bakker et al. (2003) found that high job demands predicted long absence duration due to burnout, and that a lack of sufficient job resources was the most important predictor of absence frequency due to lowered organizational commitment. Bakker et al. (2008) found a significant negative correlation between objectively observed financial performance of a work organization and burnout. In a 2012 study conducted by the University and College Union in the United Kingdom, professors who experienced elevated levels of work stress also reported higher numbers of days absent due to illness (Kinman & Wray, 2013).

Even if attending work, job performance and productivity are lower among exhausted employees (Taris, 2006). Burnout can ultimately lead to faculty attrition, which imposes both direct financial impacts to institutions, such as the cost of recruiting and hiring to replace the faculty member, and indirect impacts, such as the loss of the departing employee’s expertise and specific contribution to the organization. Burnout negatively impacts organizations in less quantifiable ways as well, including decreased program quality due to high turnover, low morale, poor work climate (including conflict among teachers and between teachers and administration, or teachers and students), and development of personal problems that can affect individual teacher performance.

Early research regarding burnout development tended to focus on internal qualities and characteristics of the employee as the central influencing factors (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017). However, Maslach and Leiter (1997) have strongly asserted that burnout is not a problem of the individual, but rather an institutional problem, observing that:

Burnout does not result from a genetic predisposition to grumpiness, a depressive personality, or general weakness. It is not caused by a failure of character or a lack of ambition. It is not a personality defect or a clinical syndrome. It is an occupational problem. (p. 34)

While internal attributes do impact how individuals tend to respond to work stressors, the bulk of the research evidence implicates job-related and interpersonal stress related to work environment as the most crucial factors in burnout development (Byrne, 1999; Nápoles, 2022). Burnout thus says more about job conditions than individuals; it is not the individual that needs to change, but work organizations or conditions (Maslach & Leiter, 1997).

Influence of Job Demands and Resources

Initially, theories about burnout development focused only on the relationship between the three dimensions of burnout: exhaustion, depersonalization/cynicism, and decreased personal efficacy. However, more recent models focus more on how job demands and resources influence burnout. Two developmental models involving job demands and resources have emerged: The Conservation of Resources (COR) theory and the Job Demands-Resource (JDR) theory (Maslach & Leiter, 2016).

The COR theory explained stress as primarily resulting from objective circumstances rather than internal personal affect or traits, specifically positing that loss of resources is the primary component in inducing work stress experienced by individuals. According to this theory, stress will occur when employees: (1) perceive a potential loss of a resource, (2) actually lose resources, or (3) do not gain sufficient resources following significant personal investment. Notably, resource loss is disproportionally more impactful than resource gain and is a better predictor of psychological distress than personal disposition, optimism-pessimism, or other individual traits such as neuroticism or introversion. In this model, burnout follows a lack of resource gain or resource losses, particularly where workers have significantly invested their time (especially personal time) and energy for low work-derived gains (Hobfoll, 2001).

Demerouti et al. (2001) subsequently developed the JDR theory to describe and predict burnout in terms of the interaction between job demands and job resources. Subsequent research has demonstrated that high job demands often negatively impact employee well-being and job performance (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007; Schaufeli & Taris, 2014), and that there is a direct negative relationship between high job demands and burnout (Bakker et al., 2005). Job stressors, particularly chronic stressors including overwhelming job demands, are the most important correlates of emotional exhaustion (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017). For example, in their study of a large group of Finnish elementary, secondary, and vocational teachers Hakanen et al. (2006) found that high job demands of teaching reduced energy and predicted the development of burnout. Insufficient job resources are similarly problematic, correlating with increased cynicism (depersonalization) and decreased efficiency (Halbesleben & Buckley, 2004). It is worth noting that not all job demands negatively impact employee wellbeing. Job demands can be considered “hindrance demands,” which tend to have a negative impact, or “challenge demands,” which potentially promote personal growth and achievement (Bakker and Demerouti, 2017).

Job resources influence job demands in complex ways. Employees are generally extremely sensitive to removal of resources, which may be perceived as a job demand. Hakanen et al. (2006) implied a dual role for job resources among Finnish educators: (1) teachers who were able access more job resources such as job autonomy, supervisory support, and innovativeness became more engaged in and committed to teaching while (2) lack of job resources sufficient to meet job demands led to burnout, which further undermined motivation and led to lowered organizational commitment. However, simply increasing job resources may not concomitantly decrease the symptoms of burnout. In fact, an overdose of job resources can also promote burnout. For example, extremely high job autonomy, often a feature of university music teaching, may not predict positive employee well-being due to the uncertainty, difficulty in decision-making, and high job responsibility implied (Bakker et al., 2005). The lens through which employees view their working environments also influences their perceptions about job demands and resources: burned-out employees are more likely to perceive and complain about high job demands, thus perpetuating a negative work climate, while more engaged employees are more likely to notice and be better able to mobilize work resources (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007).

Burnout among faculty is not entirely determined by job demands and resources. The ways in which work is organized, how schools view and treat their teachers, and how teachers are viewed and valued in the larger culture and public are also key factors in burnout development (De Hues & Diekstra, 1999). Personal resources such as self-efficacy, self-esteem, and resilience and coping behaviors temper job demands and impact the burnout process (Bermejo-Toro et al., 2016). In a study of Norwegian elementary and middle school teachers, teacher self-efficacy and autonomy was closely related to work engagement, low emotional exhaustion, and job satisfaction (Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2014). Bermejo-Toro et al. (2016) showed self-efficacy and coping skills to be even more important than job resources in a group of elementary and secondary teachers in Spain.

Burnout Among Music Faculty

As is typical for most university educators, a music faculty member’s work contributions are typically situated within the broad categories of teaching, research, and service. However, music faculty often teach in a wide variety of contexts, including traditional academic classes, supervision of undergraduate or graduate research, direction of musical ensembles, and offering applied musical instruction to individual or small groupings of students. Research often goes beyond traditional publication of articles or books to include live performance, recording, or the creation of new works. Musical performance often requires intensive and narrow focus and requires many hours of practice in isolation, as well as coping with pressures of public performance (Lee & McNaughten, 2017). It is possible that music and other arts faculties may be particularly susceptible to burnout given the long hours, low salaries, and relative scarcity of resources often encountered in arts education.

Studies of burnout among university music faculty are sparse. While not specifically focused on burnout, Lee (1995) investigated university music faculty vitality, which she defined as the individual’s capacity and dynamics that generate productive faculty work, relative to departmental conditions. She identified several departmental conditions that supported various aspects of music faculty vitality, including: participatory opportunities in shared governance (especially in decision-making processes impacting individual working conditions); career socialization opportunities (such as professional dialogues, support systems, mentoring, and collaborative opportunities); improved working conditions (assignments balanced between teaching, research/creative, and service allocations, clear job expectations, and freedom to conduct one’s own research/creative work); and supportive executive leadership. Hamann et al. (1988) assessed burnout level among fifty college music professors throughout the United States. Their participants reported slightly lower mean levels of burnout as compared to police officers, nurses, counselors, physicians, and others in the helping professions. Nevertheless, the number of music faculty reporting moderate to high burnout was significant. In a study of 36 professors at a public university school of music, Bernard (2007) examined perceived burnout levels of university music faculty in the dimensions of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal accomplishment by tenure status and primary teaching area. He observed a positive relationship between hours of class preparation and burnout (specifically emotional exhaustion and depersonalization), supporting observations by Byrne (2005) and others that work overload is a substantial contributor to teacher burnout.

There is evidence that the work burdens of university teaching are increasing. Over the last couple of decades, university educators have been impacted by a number of negative developments including the continuing erosion of work/life boundaries (with pervasive technology intruding on personal time), increasing governmental scrutiny, erosion in numbers of tenure-track positions and fewer job advancement opportunities, decreasing salaries relative to rising cost of living, and increasing workloads (American Association of University Professors, 2020).

The COVID-19 pandemic imposed even more demands upon faculty. In October 2020, The Chronicle of Higher Education conducted a study of 1,122 faculty members at four- and two-year colleges and universities throughout the United States (Chronicle of Higher Education, 2020). Half the respondents were tenured, the rest were tenure-track, nontenured, and part-time professors. More than two-thirds of participants reported feeling extremely or very stressed over the previous month compared with about one-third who reported similar feelings at the end of 2019. About 55% reported feeling little or no hope over the past month, compared with about a quarter of participants who reported feeling despondent in 2019. Fifty percent of respondents said their enjoyment of teaching had decreased. Perhaps most telling, 35% of professors had considered changing careers since the beginning of the pandemic and 38% were considering retiring.

A similar study of more than 570 full- and part-time faculty at two- and four-year colleges and universities across the United States by Course Hero (Inside Higher Education, 2020) reinforced these findings. Fifty-four percent of participants strongly agreed that the pandemic had made their jobs more difficult, while an additional 33% agreed with this statement. Transitioning to new modes of teaching caused significant stress for 74% of participants, and 40% considered leaving academia due to pandemic impacts. Nearly two-thirds of faculty said that meeting emotional and mental health needs of students imposed significant stress and nearly two-thirds expressed concerns that even after emergence from the pandemic there would be diminished perceptions of the value of higher education. Nearly half expected long-term closures or mergers with other campuses while 60% expected their institutions would cut academic programs or courses of study. More than half of faculty reported a significant increase in emotional drain and 52% reported increased work-related stress or frustration, all correlates of burnout.

While individuals respond to work stress differently and some may be more susceptible to burnout than others, music faculty often do not have direct control over specific job expectations or work environment. The bulk of the evidence suggests that it is the elements of the job and institution—including excessive job demands or a lack of resources—that lead to burnout (Nápoles, 2022). Elucidation of which specific job stressors most strongly contribute to burnout would allow institutions and administrators to develop institutional interventions. In preparation for a study using a larger research population, this preliminary study investigated a group of university music faculty to explore: (1) the relationships between three dimensions of burnout, (2) the relationships between various categories of perceptions about job conditions, and (3) the relationships between categories of job perceptions and the three dimensions of burnout.

Method

Participants and Procedures

Invitations to participate were sent via email to the music faculties at three institutions: a public Research One (Carnegie classification) & Land Grant institution with 39 full-time and 8 part-time faculty members offering bachelors, masters, and doctoral degrees to 370 music majors; a private institution with 6 full-time and 17 part-time music faculty members offering undergraduate degrees with a total of 24 music majors; and a private institution with five full-time and twenty part-time music faculty members offering undergraduate degrees to 52 music majors.

Criteria for study participating included: nineteen years of age or older; currently employed as full- or part-time faculty in a department/school of music at a college or university; having no more than 10% administrative job apportionment; and, currently in the United States of America. The survey was available online October 21 to November 30, 2021. To maintain participant confidentiality, no names, IP addresses, nor other identifiers were collected, and responses were fully anonymized in the output data file. Twenty-seven (N=27) participants met inclusion criteria, consented to participate, and filled out all research instruments sufficiently to be included. Sixteen participants identified as male, ten as female, and one preferred not to answer. Twenty-six participants described themselves as White (one participant preferred not to answer this item). Participants identified themselves as contingent/adjunct faculty (n = 3), tenure-track assistant professors (n = 2), tenured associate professors (n = 7), untenured associate professors (n = 2), tenured full professors (n = 12), and untenured full professors (n = 1). The age ranges consisted of 61-70 (n = 11), 51-60 (n = 7), 41-50 (n = 4), and 31-40 (n = 5). On average, participants had a total of 15-25 years of teaching experience and had served at their current institution for 15-25 years. Twenty-one participants were teaching at the public Research One institution, with only six participants from the music departments of the two private liberal arts universities.

Research Instruments

After consenting to participate, respondents filled out a questionnaire hosted on Qualtrics. The first set of questions collected demographic information. Participants then completed two inventories. The first was the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI), selected because it has demonstrated good validity, internal reliability, and stability over time in multiple studies (Maslach et al., 2018). The MBI measured burnout in three dimensions—including nine emotional exhaustion (EE) items, five depersonalization (DP) items, and eight personal accomplishment (PA) items—according to how often each item was experienced on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from never to every day. Since each dimension functions independently, the MBI manual explicitly directs scoring each subscale separately and cautions against combining subscales to form a single aggregate burnout score (Maslach et al., 2018). The MBI instrument generally avoids using the term “burnout” to avoid biasing participant response. For this same reason, the title of this study referred to work attitudes rather than burnout.

Coherent with the JDR theory, the researcher developed the second inventory, the University Faculty Job Perceptions Inventory (UFJPI), specifically for this study to measure perceptions of various work demands and resources. The UFJPI contained 81 individual items grouped into seven categories relating to: Job Profile & Resources; Time; Fairness & Evaluation; Salary & Benefits; Work Climate; Student Issues; and Job Relevance & Satisfaction. Participants indicated their agreement with each item on a six-point Likert scale: Strongly Disagree, Disagree, Slightly Disagree, Slightly Agree, Agree, Strongly Agree (plus a Not Applicable option). Prior to the study, the researcher sent a draft of the questionnaire items to six music faculty at various post-secondary music schools around the United States—including public and private institutions and larger and smaller music units—for informal feedback and revised items accordingly.

The words “burnout,” “stress,” or their derivatives were not used on the UFJPI to avoid response bias. Instead, instructions for the inventory referred to perceptions about “job conditions.” To increase the UFJPI’s measurement accuracy and efficacy (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988; Chang, 1995; Worcester & Burns, 1975), valence of item wording was mixed to promote careful reading of each item by participants (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Some items were framed positively (e.g., “I receive sufficient direct supervisor support or intervention”) while others were phrased negatively (e.g., “My work often precludes or intrudes upon personal time”). Items were placed into categories so that positively and negatively worded items measured the same construct. (Marsh, 1996). Prior to data analysis scores on positively worded items were reverse coded so that all high scores indicated that participants perceived the item as a job demand.

Results

In interpreting results from the MBI, it is important to remember that each subscale functions differently as an indicator of burnout on this inventory. The emotional exhaustion (EE) scale, measures feelings of being emotionally overextended and exhausted, which are often initial indicators of educator burnout. The depersonalization (DP) scale measures unfeeling and impersonal regard toward students. However, the personal accomplishment (PA) subscale, in contrast to the EE and DP subscales, measures positive feelings of competence and achievement, which are protective against the experience of burnout. Thus, a profile of higher scores on EE and DP with lower scores on PA is often consistent with the experience of burnout, though other configurations of subscale scores may also indicate burnout. For example, individuals experiencing burnout may have an exceedingly high EE score without correspondingly high DP or low PA scores. (Maslach, Jackson, & Leiter, 2018).

Following the procedure recommended in the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) manual for calculating means, items within each subscale were first summed and then a mean was calculated. Burnout means across participants for the various burnout subscales in the present study were EE = 22.93, SD = 14.19; DP = 5.04, SD = 4.48; PA = 39.52, SD = 4.77. These findings were considered against normative means provided by the MBI manual for each subscale based on data collected from 635 postsecondary (college/university) teachers: emotional exhaustion (EE) = 18.57, standard deviation (SD) = 11.95; depersonalization (DP) = 5.57, SD = 6.63; and personal accomplishment (PA) = 39.17, SD = 7.92. While the emotional exhaustion mean was higher and the depersonalization score slightly lower in the present study, these scores still fell within the standard deviation provided for the normative score. The large standard deviations within both datasets are notable, demonstrating wide variance of individual scores on the three burnout subscales. Burnout subscale scores in the present study were not appreciably different than the norms provided by the MBI manual.

Using IBM SPSS Statistics version 28 and adopting a significance level of p < .05, Pearson product-moment correlations (N = 27) were calculated to determine the relationships between the three subscales of the MBI inventory, relationships between categories on the UFJPI, and relationships between UFJPI categories and MBI subscales. There was a significant positive correlation between scores on the EE and DP burnout subscales (r = .719, p < .001). However, there were no significant relationships observed between PA and either EE or DP. These findings echo the observation by Maslach and others that burnout is not a unidimensional construct.

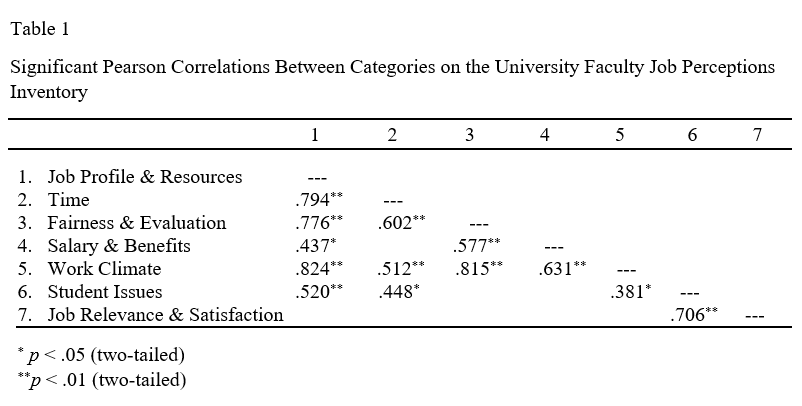

Cronbach’s alpha was calculated for items within each category on the UFJPI. Internal consistency was generally acceptable (α > .70) with exception of the categories of Salary & Benefits, where one item was identified as inconsistent with the category, and Job Relevance & Satisfaction, where additional analysis suggested two items may have been collinear (measuring the same thing). Salary & Benefits only had four items, so it is possible that the lower Cronbach for this category is incidental given the small number of participants. Nevertheless, caution should be exercised in drawing any conclusions about relationships involving these categories. As anticipated, several significant correlations were observed between various UFJPI categories, as shown in Table 1.

Finally, Pearson product-moment correlation coefficients were calculated to explore relationships between the emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal accomplishment MBI subscale scores and participant mean scores in each of the seven UFJPI categories. Scores on the EE burnout subscale positively correlated with the categories of Job Profile & Resources (r = .725, p < .001), Time (r = .657, p < .001), Fairness & Evaluation (r = .549, p = .003), Work Climate (r = .600, p = .003), and Student Issues (r = .408, p = .035). Scores on the DP burnout subscale positively correlated with the categories of Job Profile & Resources (r = .541, p = .004), Time (r = .478, p = .012), Work Climate (r = .450, p = .018), and Student Issues (r = .580, p = .002).

Discussion

The MBI manual, citing Dworkin and Tobe (2014), noted that longitudinal studies suggest that burnout rates among teachers have trended upward over time (Maslach et al., 2018). Moreover, the data in the present study were collected in Fall 2021, immediately following major disruptions and additional demands placed upon collegiate music faculty due to the pandemic. Participants were required to quickly pivot to exclusively remote instruction in Spring 2020 only to encounter another major upheaval to hybrid instruction involving teaching simultaneously in-person and remotely in Fall 2020 and Spring 2021. It was therefore surprising that the means on the emotional exhaustion and depersonalization subscales of the MBI did not differ significantly from the 2018 pre-pandemic norms. Concomitant with the present study, a separate study conducted by Gallup measured work climate across the same public university system—which employed 21 of the 27 participants in the present study—and reported a similar finding: one-third of employees in that study, including roughly two in five women, said they struggled with burnout “always” or “very often.” These readings, however, were at least ten points lower than national averages (Gallup, Inc., 2022).

These lower-than-expected burnout rates may represent a context effect. The Fall of 2021 represented a return to fully in-person classroom instruction at all institutions from which participants were drawn. It is plausible that faculty perceptions of burnout were relatively lower against the backdrop of extreme disruptions imposed during the previous three semesters. Faculty may have simply been so relieved to be teaching in person, without undue burdens imposed from simultaneously managing remote instruction, that they temporarily reported lower burnout levels. Another possible explanation for this finding is the age of the participants in the current study (with all but five aged 41 or above), since previous studies have demonstrated that younger faculty are more vulnerable to emotional exhaustion than older faculty (Watts & Robertson, 2011). Collecting data mid-semester may have also impacted MBI scores. In any case, while burnout scores in the present study were similar to pre-pandemic normative means provided by the MBI, these scores are still quite high. While there is no definitive score on the MBI that identifies an individual as being “burned out,” burnout is clearly a major concern among university music faculty.

While there was a strong positive correlation between subscales measuring the burnout dimensions of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization, it is interesting that no relationships were observed between personal accomplishment and other burnout subscale scores among this group of participants. Similarly, there were no relationships between scores on personal accomplishment and any category of job perceptions. It is possible that these participants’ views about their own accomplishment functioned independently from their level of emotional exhaustion or degree of cynicism toward students or their job. It is also possible that the small number of participants obscured a relationship between personal accomplishment and the other MBI subscales or UFJPI categories. In any case, this finding further underscores the importance of measuring the three dimensions of burnout separately.

With regard to relationships between UFJPI categories, it is notable that Job Profile & Resources correlated with every other category except for Job Relevance & Satisfaction. Though the direction of the relationship cannot be determined from these data, this finding is consistent with a lack of resources or dissatisfaction with job profile strongly influencing the experience of other aspects of the job. Similarly, the positive relationships between the Fairness & Evaluation, Salary & Benefits, and Work Climate categories are logical given the interrelatedness of these areas of work experience. The number of significant relationships between the Work Climate and Student Issues categories and other categories are also notable in this regard.

Particularly where strong correlations >.70 emerged, the UFJPI may benefit by careful combination or elimination of items prior to future administrations since there may have been some convergence of individual items between categories. However, the strength of the correlations observed between categories also provides limited evidence to support discriminant validity of this new instrument, indicating that the seven categories of items measured different experiences. Stronger correlation coefficients greater than .850, which were not found in the present study, might have indicated that items in various categories were measuring the same construct (Henseler et al., 2015). Cronbach scores for items within UFJPI categories indicated acceptable reliability, with exception of the Salary & Benefits category where one item was shown to be inconsistent with the others, and Job Relevance & Satisfaction, where two items were collinear. Elimination or combination of these individual items will improve consistency for future use of this inventory.

Exploration of the relationships between participant job perceptions and scores on the emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal achievement subscales of the MBI was a primary interest of this study. Several categories on the UFJPI positively correlated to higher scores on the emotional exhaustion and depersonalization subscales of the MBI. The Job Profile & Resources and Time categories positively correlated with higher scores on both the emotional exhaustion and depersonalization subscales with the strength of the correlation between Job Profile & Resources and emotional exhaustion particularly noteworthy. This finding suggests that this group of university music faculty might benefit from job crafting, in which the institution might empower faculty to change job responsibilities, allow for time off, allocate time in accordance with job commitments, or create more collaborative experiences (Lee & McNaughtan, 2017; Tims et al. 2012). Work Climate, Fairness & Evaluation, and Student Issues significantly related to both emotional exhaustion and depersonalization, highlighting additional areas where participants’ institutions might productively apply resources toward lowering faculty stress.

Given the small number of participants and the design of this study, the findings need to be interpreted with caution. This study employed cross-sectional data collection and thus could not examine whether or how participants’ perceptions about their jobs or scores on the three burnout dimensions may have changed over time. Furthermore, given that all data were self-reported, participants may have selected responses they believed to be more socially acceptable rather than those that more accurately represented their experiences. Additionally, since the invitation to participate was extended to all faculty at the three institutions chosen, sampling bias cannot be excluded. Finally, the participant group for this exploratory study was limited in size and scope, consisting of faculty teaching at institutions within a small geographic region. For all these reasons, findings cannot be widely generalized.

This exploratory study employed a new inventory, the UFJPI, for measuring perceptions regarding job conditions among university/college music faculty. Though informal feedback from university professors at various institutions in the United States supports general content validity, it is possible that the UFJPI did not address all the potential conditions that might color music faculty perception about job experience. While internal checks provided by Qualtrics indicated that the length and appearance of the research instrument was conducive to participant completion, it is possible that respondents may not have read each item carefully. Additionally, some participants skipped individual items on the UFJPI inventory. Finally, it is possible lower burnout scores may have diluted the power of the analysis across all participants and obscured job perceptions associated with higher levels of burnout. Forcing a response on each item will prevent this potential problem in future studies using these research instruments. Subsequent administration of the UFJPI research instrument to a larger participant group will support exploratory factor analysis to further examine reliability and will provide sufficient statistical power for logistical regression or structural equational modeling to identify which categories and individual items predict scores on the different subscales of the MBI.

Most of the participants in this study were tenured full professors and had many years of teaching experience, and no members of underrepresented ethnic, race, or gender identity groups chose to participate. Future study will determine which job conditions contribute to burnout scores across a much larger group of college/university music faculty across a broader range of institutions, allowing for better generalizability and illustrating patterns of job demands and resources as predictors of burnout. Comparative study of larger university faculty populations across multiple academic disciplines may identify discipline-specific patterns of job demands or resources contributing to burnout. Additional study of how various demographic factors—including full- versus part-time employment, gender/sexual identification, ethnicity, race, family status, and years of work experience among others—moderate the experience of job demands and resulting work attitudes may help identify additional burnout risk factors.

College/university administrators are awakening to institutional costs of burnout. Unfortunately, institutional responses have typically consisted of touting the importance of faculty “self-care,” a response that only increases the burdens placed upon university music faculty. Music faculty can learn strategies to moderate their reaction to job stressors or, within parameters, engage in job crafting to change job responsibilities, allow for time off, allocate time in accordance with job commitments, or create more collaborative experiences (Lee & McNaughtan, 2017). However, individual faculty members often have little control of the demands and lack of resources imposed directly by the job and the institution. The faculty project the core mission of colleges and universities. Institutions have a vested financial interest in preventing monetary loss due to increased illness, disability, and attrition and reduced quantity and quality of work due to burnout. Additionally, most institutions aspire to build and maintain a sustainable environment where faculty and students flourish. Existing research clearly points to job demands and resources as primary factors in the development of burnout. Illuminating which specific job demands and resources predict burnout among music faculty thus offers a path toward developing meaningful institutional interventions, though subsequent repeated-measures research will be needed to evaluate which kinds of interventions are most efficacious.

References

Ahola, K, & Hakanen, J. (2014). Burnout and health. In M.P. Leiter, A.B. Bakker, & C. Maslach (Eds.), Burnout at work, 10-31. New York: Psychology Press.

American Association of University Professors (2020). The annual report on the economic status of the profession, 2019-2020. Washington, D.C.: American Association of University Professors.

American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association (2014) National Council on Measurement in Education. Standards for educational and psychological testing. Washington: American Educational Research Association.

Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: a review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103, 411–423.https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411

Bakker, A. B. and Demerouti, E. (2007). The job demands-resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology 2(3), 309-328. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940710733115

Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2017). Job demands-resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(3), 273-285. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000056

Bakker, A. B.; Demerouti, E.; and Euwema, M. C. (2005). Job resources buffer the impact of job demands on burnout. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 10(2), 170-180. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/1076-8998.10.2.170

Bakker, A. B., Van Emmerik, H., and Van Riet, P. (2008). How job demands, resources, and burnout predict objective performance: A constructive replication. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping, 21, 309-324. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615800801958637

Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., De Boer, E. & Schaufeli, W. B. (2003). Job demands and resources as predictors of absence duration and frequency. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 62, 341-356. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0001-8791(02)00030-1

Bermejo-Toro, L., Prieto-Ursúa, María, Hernández, V. (2016). Towards a model of teacher well-being: Personal and job resources involved in teacher burnout and engagement. Educational Psychology, 3(3), 481-501. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2015.1005006

Bernhard, H. C. II (2007). A survey of burnout among university music faculty. College Music Society Symposium, 47, 117-126. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40374508

Byrne, B. (2005). The nomological network of teacher burnout: A literature review and empirically validated model. In R. Vandenberghe & A. M. Huberman (Eds.), Understanding and preventing teacher burnout: A Sourcebook of international research and practice, 15-37.

Chang, L. (1995). Connotatively consistent and reversed connotatively inconsistent items are not fully equivalent: generalizability study. Educational and Psychological. Measurement 55, 991–997. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164495055006007

Chronicle of Higher Education with support from Fidelity Investments (2020). On the verge of burnout: Covid-19’s impact of faculty well-being and career plans. Retrieved February 3, 2021, https://connect.chronicle.com/rs/931-EKA218/images/Covid%26FacultyCareerPaths_Fidelity_ResearchBrief_v3%20%281%29.pdf

De Hues, P. & Diekstra, R. F. W. (1999). Do teachers burn out more easily? A comparison of teachers with other social professions on work stress and burnout symptoms. In R.Vandenberghe & A. Michael Huberman (eds) Understanding and preventing teacher burnout: A sourcebook of international research and practice. Cambridge, UK:Cambridge University Press.

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., and Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands-resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 499-512. https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-9010.86.3.499

Dubois, A. L., & Mistretta, M. A. (2020). Overcoming burnout and compassion fatigue in schools: A guide for counselors, administrators, and educators. New York: Routledge.

Dworkin, A. G. & Tobe, P. F. (2014). The effects of standards-based school accountability on teacher burnout and trust relationships: a longitudinal analysis. In Trust and school life, 121-143. Netherlands: Springer.

Gallup, Inc. (2022). “University of Nebraska System Climate Study: The Student, Faculty, and Staff Experience,” page 5. Retrieved May 13, 2022 from https://nebraska.edu/transparency/campus-climate-safety-reports

Hakanen, J. J., Bakker, A.B. & Schaufeli, W. B. (2006). Burnout and work engagement among teachers. Journal of Social Psychology, 43, 495-513.https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1016/j.jsp.2005.11.001

Hakanen, J. J., Schaufeli, W. B. & Ahola, K. (2008). The job demands-resources theory: A three-year cross-lagged study of burnout, depressions, commitment, and work engagement. Work & Stress, 22, 224-241. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02678370802379432

Halbesleben, J. R. B., & Buckley, M. R. (2004). Burnout in organizational life. Journal of Management, 30, 859-879. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jm.2004.06.004

Hamann, D. L., Daugherty, E., & Sherbon, J. (1988). Burnout and the college music professor: An investigation of possible indicators of burnout among college music faculty members. Council for Research in Music Education, 98, 1-21. https://www.jstor..org/stable/40318240.

Henseler, J., Ringle, C.M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43, 115-135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

Hobfoll, S. E (2001). The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: Advancing Conservation of Resources theory. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 50(3), 337-421. https://doi.org/10.1111/1464-0597.00062

Inside Higher Education (2020). Faculty Pandemic Stress is Now Chronic. Retrieved January 28, 2021 from https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2020/11/19/faculty-pandemic-stress-now-chronic.

Kinman, G. & Wray, S. (2013). Higher Stress: A survey of Stress and Well-being Among Staff in Higher Education. University and College Union (report on occupational stress in higher education). www.ucu.org.uk.. Retrieved January 28, 2021.

Lee, S-H. (1995). Departmental conditions and music faculty vitality. (Order No. 9527679) [Doctoral Dissertation, University of Michigan]. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses.

Lee, S-H. and McNaughtan, J. (2017). Music faculty at work in the academy: Job crafting. College Music Symposium,57. https://doi.org/10.18177/sym.2017.57.sr.11364

Marsh, H. W. (1996). Positive and negative global self-esteem: a substantively meaningful distinction or artifactors? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 70, 810–819. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.70.4.810

Maslach, C. & Leiter, M. P. (1997). The truth about burnout: How organizations cause personal stress and what to do about it. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Maslach, C. & Leiter, M. P. (2016). Understanding the burnout experience: recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry, 15, 103-111.https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20311

Maslach, C., Jackson, S. E., & Leiter, M. P. (2018). Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual, Fourth Edition. Mind Garden, Inc.

Nápoles, J. (2022). Burnout: A review of the literature. Update: Applications of Research in Music Education, 40(2), 19-26. https://doi.org/10.1177/87551233211037669

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology 88, 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Savic, I. (2013). Structural changes of the brain in relation to occupational stress. Cerebral Cortex, 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678370802379432

Schaufeli, W. B. “Burnout: A Short Socio-cultural History” (2017) In Necket, S., Schaffner, A. K., & Wagner, G. (Eds.) Burnout, fatigue, exhaustion: An interdisciplinary perspective on a modern affliction. 105-127. Cham Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.

Schaufeli, W. B. and Taris. T.W. (2014). A critical review of the job demands-resources model: Implications for improving work and health. In Bauer, G. & and Hammig, O. (Eds.), Bridging occupational, organizational and public health, 43-68. Dordrecht: Springer.

Skaalvik, E. M. and Skaalvik, S. (2014). Teacher self-efficacy and perceived autonomy: Relations with teacher engagement, job satisfaction, and emotional exhaustion. Psychological Reports 114 (1), 68-77. https://doi.org/10.2466/14.02.PR0.114k14w0

Taris, T. W. (2006). Is there a relationship between burnout and objective performance? A critical review of 16 studies. Work & Stress, 20, 316-334. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678370601065893

Tims, M., Bakker, A. B., and Derks, D. (2012). Development and validation of the job crafting scale. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80 (1), 173-186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2011.05.009

Watts, J. & Roberson, N. (2011). Burnout in university teaching staff: A systematic literature review. Education Research, 53, 33-50. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131881.2011.552235

Worcester, R. M., and Burns, T. R. (1975). Statistical examination of relative precision of verbal scales. Journal of the Market Research Society, 17, 181–197.