Abstract

Purpose: The purpose of this study was to 1) evaluate the incidence of noise-induced hearing loss (NIHL) of freshman students who participated in organized music activities prior to attending college; 2) provide subjects with personalized, comprehensive baseline audiometric hearing threshold data; 3) determine the extent to which subjects regularly used hearing protection during music rehearsals and performances; 4) educate subjects on proper ways to protect hearing health when rehearsing and performing.

Methods: Using standardized testing procedures, an audiometric hearing examination was administered to 21 subjects. Test results outlining each subject’s hearing threshold at various octaves and half-octaves between the test frequencies of 500 Hz and 8000 Hz were obtained and shared with subjects. The subjects self-reported the extent to which they regularly used hearing protection during music rehearsals and performances. Information on the implementation of proper hearing health techniques while rehearsing and performing music were individually shared with subjects.

Results: Hearing test results for 86% of subjects (n = 18) indicated NIHL in either one or both ears. Of these, 24% of subjects (n = 5) exhibited NIHL in both ears, while 62% of subjects (n = 13) exhibited NIHL in one ear. The remaining 14% of subjects (n = 3) either exhibited no signs of hearing loss, or hearing losses of 5 dB or less. Also, 14% of subjects (n = 3) reported regularly using hearing protection during music rehearsals and performances, though the audiometric results for these subjects indicated each subject exhibited NIHL.

James A. Grymes

The Incidence of Noise-Induced Hearing Loss among Freshman Students Who Participated in Organized Music Activities Prior to Attending College

Introduction

Noise-induced hearing loss (NIHL) is defined as a permanent loss of hearing resulting from exposure to substantially high sound pressure levels (Harding & Owens, 2004; Zeigler, 1997). Developing gradually over time as a function of continuous or intermittent exposure to noise greater than what the human ear can safely tolerate, NIHL is different from hearing loss caused by sudden acoustic trauma which typically results from a single exposure to a sudden burst of sound, such as an explosive blast (Miraza et al. 2018; NIOSH, 1998; NIDCD, 2019). Since the entire population is susceptible to NIHL, this condition has gained increased attention from the public, government agencies, and health care providers (Owens, 2008).

NIHL is a major health issue (Owens, 2008), as it is estimated that approximately 15% of American adults between the ages of 20 and 69 exhibit some type of hearing loss (Agrawal et al., 2008; NIDCD, 2019). More alarmingly, college-aged students have recently been shown to suffer from varying levels of NIHL and from the array of symptoms associated with NIHL. For example, Barlow (2011) found that 44% of college-aged students studying popular music showed some evidence of NIHL while Miller et al. (2007) reported 63% of student musicians experienced tinnitus, otherwise known as ringing in the ears, after being exposed to loud music. Owens and Schwartz (2021) also reported that student musicians suffered from bouts of tinnitus because of exposure to loud noises.

Though the incidence of NIHL in occupational settings, particularly for industrial workers, is well documented (NIOSH 2022; Miraza et al. 2018; OSHA, 1983), and though some studies exist regarding the occurrence of NIHL in musicians and those who teach music (Axlesson & Lindgren, 1981; Cutietta et al., 1989; Cutietta et al., 1994; Harding & Owens, 2004; Henoch & Chesky, 2000; Owens, 2004), the general concept of hearing health is not well understood in this population. Indeed, concerns about potential hearing loss resulting from conducting an orchestra or band, playing an instrument, singing, or teaching music have been largely ignored. This is particularly true for musicians involved in collegiate and public-school music programs (Harding & Owens, 2004; Owens & Schwartz, 2021), a disturbing fact since some musicians might be more “at risk” than industrial workers due to excessive exposure to high sound pressure levels experienced over prolonged periods (Henoch & Chesky, 2000).

Musicians may be more susceptible to hearing loss due to the large amounts of time spent playing in rehearsal and performance settings, with the amount of loss related to the intensity of the noise, duration and intermittency of exposure, and total exposure over months and years. For example, Cutietta et al. reported in 1989 that 41% of high school band directors showed some sign of NIHL, whereas in 1994 Cutietta et al. concluded that there was some risk to high school band directors for the development of NIHL, though the authors concede that the degree of risk might vary widely among individuals. More recently, Henoch and Chesky (2000) demonstrated that musicians associated with a college jazz band ensemble may be at risk for hearing loss, whereas Owens (2004) reported that 60% of venues where band directors work exposed directors to noise levels that exceeded safe industry standards. In addition to recognizing that band directors and the like are at an increased risk of developing NIHL, noise levels in singing environments have also been shown to be higher than what is acceptable (Sataloff et al., 1997). This fact also places singers at an increased risk for developing NIHL, particularly when these musicians perform and rehearse without taking the proper precautions to protect hearing health.

Although it has been established that regularly wearing hearing protection can help reduce the incidence of NIHL to those exposed to loud noises (NIOSH 2022; OSHA, 1983), it has been reported that musicians do not consistently wear hearing protection. To this point, Zeigler (1997) found that though 18.5% of university music majors either occasionally or regularly wore hearing protection during rehearsal, 81.5% admitted to never using hearing protection in this setting. Zeigler also reported 93.5% of university music majors admitted that they never wore ear protection when performing in concerts. Miller et al. (2007) found that less than one-third of music students used ear protection while playing their instruments. Owens and Schwartz (2021) recently reported that less than half of university student musicians consistently used hearing protection while performing and during rehearsal.

Since exposure to high sound pressure levels can affect hearing health, and given that a comprehensive hearing examination is necessary to attribute hearing loss to noise, the main purpose of this study was to evaluate the incidence of NIHL among freshman students who participated in organized music activities prior to attending college. The researchers aimed to determine the extent to which these students regularly used hearing protection during rehearsals and performances. Finally, the study provided the participants with personalized, comprehensive baseline audiometric hearing threshold data that they could use for future reference, and educated the participants on proper ways to protect hearing health when practicing and performing.

Methodology

After receiving approval for study implementation from the university’s IRB, participants were recruited from enrolled freshman music majors and those with a history of formal involvement in music activities at two universities in northern New England. Potential participants were offered an opportunity to have a hearing test performed to determine the extent to which they might suffer from NIHL. Students were also offered an opportunity to receive individualized feedback regarding both the results of the testing and ways to maintain hearing health while rehearsing and performing. Ultimately, 21 qualified participants volunteered for the study.

After completing the informed consent process, the participants were asked to complete a History of Music Training and Practice Hours Reporting form which documented the years of experience each participant had playing a primary, secondary (if applicable), and tertiary (if applicable) instrument(s), with “voice” being considered an “instrument.” Participants self-reported the average number of hours practicing and performing per week for each of these instruments and noted the extent to which they regularly used hearing protection during music rehearsals and performances. Noise exposure experienced by the participants within the 24 hours preceding testing, and any known history of hearing loss were also documented. Finally, the age and sex of each participant were recorded. A state licensed audiologist and/or a student training to be an audiologist individually reviewed the contents of the History of Music Training and Practice Hours Reporting form with each participant. The audiologist then explained the testing procedures and answered questions from the participants.

Prior to performing audiometric testing, the participants received a standard otoscopic observation of each ear canal to rule-out the presence of excessive cerumen, or wax build-up in the ear canal, as an excessive build-up of cerumen has been shown to affect normal hearing (Michaudet & Malaty, 2018). Subsequently, using standardized audiometric testing procedures as described by Owens (2008) and Agrawal et al. (2008), the audiologist performed a standard hearing examination using a clinical audiometer that produced pure tones that were presented to the participants via air conduction. To exclude extraneous noise interference and to assure the participants could accurately respond to the various pulsed pure tones associated with the test, the participants wore standard Telephonics TDH-39 audiometric headphones, and testing occurred in a separate room isolated from other activities.

Test results were recorded on a standard audiogram form that outlined each participant’s hearing threshold at various octaves and half-octaves between the test frequencies of 500 Hz and 8000 Hz. Participants displaying a loss of hearing acuity at any point across this spectrum were determined to suffer from NIHL. At the conclusion of testing, each participant was provided with a copy of their audiogram and the testing audiologist provided an explanation of the significance of the results. The audiologist and study authors then introduced the participants to hearing-loss prevention strategies.

Results

The age range of the participants was between 18 and 24 years (M = 19.8) with 9 females and 12 males participating. Among all participants, the mean years of musical experience for the primary instrument was 8.29 years (SD = 2.86; Range = 7 - 13 years), with participants participating in strings, woodwinds, brass, percussion, piano, and voice.

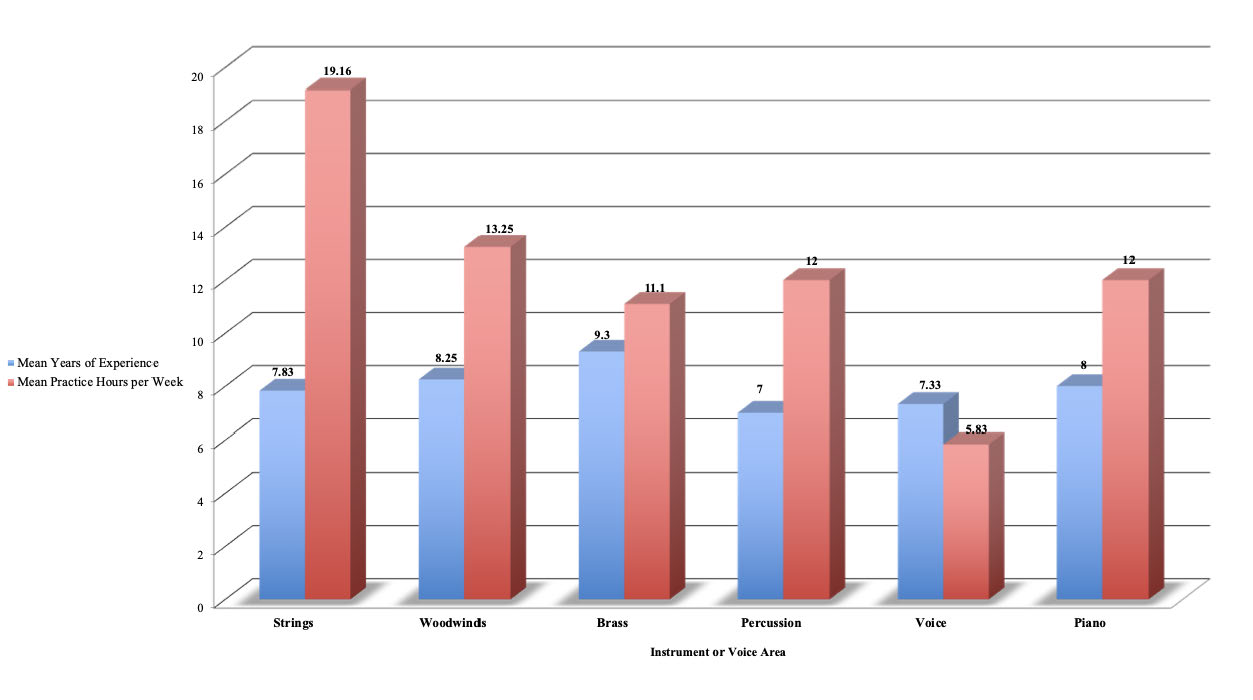

The mean number of rehearsal and/or performance hours per week on the primary instrument reported by the participants was 11.76 hours (SD = 7.39; Range = 1 – 35 hours per week). The participants from the string instrument area (n = 3) reported the greatest number of rehearsal and performance hours (M = 19.16 hours). The mean age range and the mean number of rehearsal and/or performance hours per week are listed in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Mean Years of Musical Experience and Mean Number of Rehearsal and/or Performance Hours Per Week by Instrument/Voice (N = 21)

Furthermore, 62% (n = 13) of the participants reported studying a secondary instrument, with the mean years of performance equaling 7.3 years (SD = 5.45; Range = 1 – 19 years). The mean number of rehearsal and/or performance hours for this sample was 5.19 hours per week (SD = 3.69; Range = 1 – 12 hours per week). Additionally, 29% (n = 6) of the participants studied a tertiary instrument, with the mean years of performance equaling 5.5 years (SD = 3.72; Range = 3 – 12). The mean number of rehearsal and/or performance for this sample was 2.66 hours per week (SD = 2.06; Range = 0 – 5 hours per week).

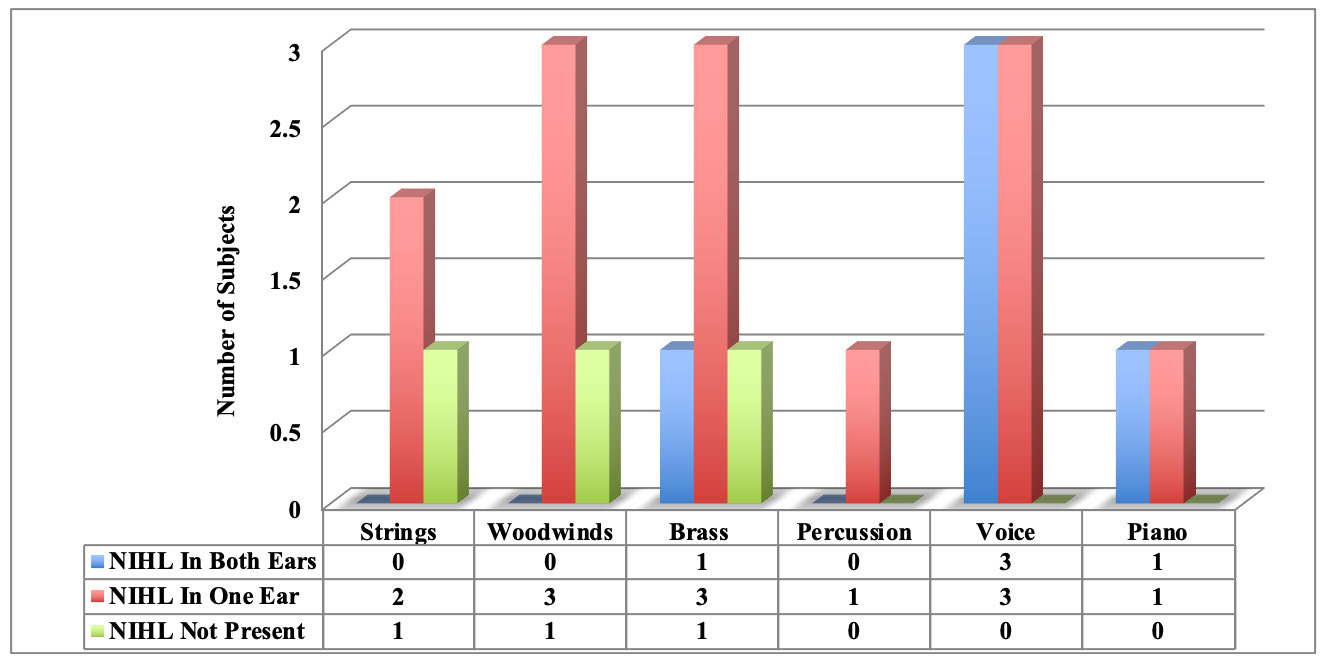

The audiometric hearing test results for 86% (n = 18) of the participants indicated the presence of NIHL in either one or both ears. Of these, 24% (n = 5) of the participants exhibited the presence of NIHL in both ears, while 62% (n = 13) of the participants exhibited the presence of NIHL in one ear. The remaining 14% (n = 3) of the participants either exhibited no signs of hearing loss or exhibited hearing losses of 5 dB or less.

Figure 2 displays the finding of NIHL across the participants based on their primary instrument. Although 14% of the participants (n = 3) reported the regular use of hearing protection during music rehearsals and performances, the audiometric results for these participants indicated each had some level of NIHL.

Figure 2. Hearing Condition of the Subjects by Instrument/Voice (N = 21)

Discussion

NIHL can occur due to a single exposure to excessive noise levels, or can develop gradually over time, resulting from long exposure to noise above levels that are safe for human hearing. (Miraza et. al.; 2018; NIOSH, 1998; NIDCD, 2019). Thus, it is not surprising that musicians are susceptible to this condition. When NIHL occurs, the hair cells of the inner ear are damaged (Owens, 2008). This directly affects a person’s hearing acuity (NIDCD, 2019). In these instances, the affected individual’s ability to hear and understand speech is diminished, particularly when placed in noisy situations (Owens & Schwartz, 2021). In addition, the onset of tinnitus is common in those whose who have been exposed to increased noise levels (National Institutes of Health, 1990). College music majors report experiencing bouts of tinnitus more frequently than do students who major in disciplines other than music, and although it has been documented that all musicians may experience tinnitus, percussionists and vocalists seem to be greatly affected by this condition (Zeigler, 1997).

When a person’s hearing is temporarily affected by excessive noise levels, the symptoms associated with NIHL may subside over time. When this occurs, the hair cells of the inner ear are not damaged permanently and, thus, after a few minutes, the person’s hearing acuity returns to baseline levels or, in more severe cases, levels return to baseline after a few hours (NIOSH, 1998). However, if left unchecked, prolonged exposure to high levels of noise can permanently damage inner ear hair cells, resulting in life-long hearing problems (Miller, 1974). For the musician, this can lead to an inability to effectively rehearse and perform (Owens & Schwartz, 2021). Unfortunately, when NIHL develops over time, the affected individual may be unaware that hearing loss is occurring (National Institutes of Health, 1990).

Since it is well established that musicians, and those involved in teaching music and directing ensembles are at risk of developing NIHL (Harding & Owens, 2004; Axlesson & Lindgren, 1981; Cutietta, et al., 1989; Cutietta, et al., 1994; Owens, 2004; Henoch & Chesky, 2000), it is no surprise that the audiometric hearing test results from this study confirmed the presence of NIHL in either one or both ears in 86% of the participants. However, of interest are the relatively young ages of the affected participants, a finding that supports the results reported by Barlow (2011) and Philips et al. (2008) but contrasts findings of Owens and Schwartz (2021), who documented minimal incidence of NIHL among this population. Conversely, Owens and Schwartz (2021) report that that 40% of tested participants self-reported experiencing common symptoms associated with hearing loss while Miller (2007) found that 63% of musicians reported at least one instance of tinnitus across their years of playing an instrument. However, the fact that musicians in this relatively young age group are experiencing NIHL is troubling. Given these data, the potential exposure to loud sounds that produce hearing loss symptoms is of major concern. Information regarding hearing protection and the possibility of experiencing NIHL from various sources needs to be shared and reinforced with young musicians.

The fact that 27% of affected participants in the present study exhibited the presence of NIHL in both ears is of interest. Also, the present study results documented the incidence of NIHL in at least one person across all instrument groups played by the participants. Thus, although all individuals can benefit from having a comprehensive baseline audiometric threshold hearing examination (Mirza et al., 2018), given the consequences that NIHL can have on a performing artist, it is imperative that musicians obtain a baseline hearing test. Sataloff and Sataloff (1991) emphasize the importance of such an examination, stating that when NIHL is diagnosed the specific type of loss can be identified and a patient-specific treatment plan can be developed. Chasin (2006) states that such an examination should be specific to each performer since musicians present a wide range of rehearsal and performance styles and types.

Following the baseline hearing examination, musicians should undergo regular hearing examinations, especially when exposure habits change to louder environments (Owens, 2008). Regular, comprehensive hearing examinations also can identify hearing loss concerns that may not be related to playing a musical instrument (Chasin, 2006). Unfortunately, regular hearing testing does not occur in this population (Zeigler, 1997), a fact not isolated to musicians, as the average American citizen does not have their hearing checked on a regular basis (Mirza et al., 2018). This is an interesting fact since hearing impairment associated with noise exposure can occur at any age (Agrawal et al., 2008; NIDCD, 2019).

The finding that only three participants (14%) in the current study reported the regular use of hearing protection during rehearsals and performances is not surprising, as it has been established that not all musicians use hearing protection in these instances (Owens, 2008; Zeigler, 1997; Owens & Schwartz 2021; Miller et al., 2007). However, the effectiveness of using hearing protection among those who are exposed to loud noises is well documented (NIOSH 2022; OSHA, 1983), and both generic and custom-made hearing protection devices for musicians are available (Miller et al., 2007; Santucci, 2009). Thus, all musicians would be well advised to always wear hearing protection during rehearsals and performances, although more research in needed in this regard as studies quantifying the true effectiveness of hearing protection devices for musicians are currently lacking (Santucci, 2009).

As the results of this study suggest, students typically have extensive years of experience of either playing a musical instrument and/or singing in environments prior to entering college. Unfortunately, it has been documented that these environments do not always lend themselves to good hearing health, as such practice environments have been found to expose students to noise levels that exceed NIOSH guidelines (Owens, 2004). This fact is supported by Owens and Schwartz (2021), who suggest that some ensemble rehearsal rooms may not be of sufficient size for the sound produced by participants and/or may not be designed with the needed sound absorption and reflection capacities necessary to avoid exposure to high sound pressure levels. Furthermore, placing musicians too close to each other in the rehearsal and performance settings may also expose musicians to increased noise. According to Henoch and Chesky (2000), brass and percussion instruments, which typically produce loud sounds, are often placed within proximity of each other in ensembles. This is ill advised, as doing so can increase the potential of noise-induced hearing harm to both those who play, and those seated near, these instruments.

All musicians should consider taking several measures to protect their hearing health. Avoid practice and rehearsal venues in which sound pressure levels exceed 85 dB (NIOSH, 1998). When doing so is not possible, the use of hearing protection is advised. Accurate sound pressure applications are now available for smartphones; use the apps to determine noise exposure levels in the rooms used for playing and adjust rehearsal space accordingly (Owens, 2008).

The rehearsal of music at a consistently lower dynamic during practice sessions may reduce exposure levels (Zeigler, 1997). The amount of noise exposure can potentially be modified by strategically positioning instruments during rehearsal and performance (Santucci, 2009). Modifications to practice and rehearsal times may reduce the exposure time to high sound pressure levels (Owens & Schwartz, 2021). Also, adjusting the number of students in a rehearsal and/or performance space may reduce the amount of noise exposure (Owens & Schwartz, 2021).

Use hearing protection during all forms of rehearsals and performances. Musicians should consider obtaining custom ear molds with removable filters, or the use of an electronic hearing protection device (Owens, 2008). Use hearing protection in all other non-musical situations, such as when running a lawn mower, using a chainsaw, attending live musical events, etc., where sound pressure levels exceed 85 dB (Zeigler, 1997).

Musicians should have their hearing examined regularly. To develop baseline data and to determine the extent to which NIHL already exists, obtain an initial, comprehensive audiometric threshold hearing examination by a trained audiologist (Mirza et al., 2018; Sataloff & Sataloff, 1991). After the first exam, obtain periodic audiometric threshold hearing examinations (Chasin, 2006), especially when exposed to louder than normal environments for extended periods of time (Owens, 2008).

Musicians should consider the physical space available in the rehearsal environment. To avoid direct exposures to loud sounds, increase the amount of space between musicians during rehearsals and performances (Henoch & Chesky, 2000). Seat musicians who play instruments that produce loud sounds, such as brass players and percussionists, far away from each other in ensemble and like situations (Henoch & Chesky, 2000; Santucci, 2009).

Additionally, musicians can decrease exposure to increased noise levels by using in-ear monitoring systems (Santucci, 2009); by placing audio speakers above ear height and placing the upper brass instruments on risers (to avoid playing directly into the ears of other musicians), and by using baffles for sound absorption (Chasin, 2009).

Conclusion

For musicians, any type of hearing loss can be a career-changing event as the onset of NIHL can force changes in the way a musician rehearses and performs. At the very least, when the symptoms of NIHL occur, a musician becomes aware of the effect a loud playing environment has on hearing health. Unfortunately, the results of this study indicate that students with a history of signing or playing a musical instrument potentially enter college with some level of NIHL already present in one or both ears. Furthermore, these students may not regularly be using hearing protection while rehearsing and performing. Both findings are disturbing given that NIHL is a preventable condition. However, by implementing some simple intervention strategies, all musicians can prevent NIHL from occurring.

REFERENCES

Agrawal, Y., Platz, E., & Niparko, J. (2008). Prevalence of hearing loss and differences by demographic characteristics among US adults: Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999-2004. Archives of Internal Medicine 168(14),1522-1530.

Axlesson A., & Lindgren F. (1981). Hearing in classical musicians. Acta Otolaryngologica 91, sup377, 3-74. https://doi.org/10.3109/00016488109108191

Barlow, C. (2011). Evidence of noise-induced hearing loss in young people studying popular music. Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 26(2), 96-101. https://doi.org/10.21091/mppa.2011.2014

Chasin, M. (2006). Hearing aids for musicians. Hearing Review, 13(3), 18-27.

Chasin, M. (2009). Hearing loss in musicians: Prevention and management. Plural Publishing.

Cutietta, R., Millin J., & Royse D. (1989). Noise induced hearing loss among school band directors. Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education 101,41-49. Cutietta, R., Klich R., Royse, D., & Rainbolt, H (1994). The incidence of noise induced hearing loss among music teachers. Journal of Research in Music Education 42(4), 318-330. https://doi.org/10.2307/3345739

Harding, R., & Owens D. (2004, January 8-11). Colorado music educators hearing threshold project. Proceedings of the Hawaii International Conference on Arts and Humanities, Honolulu, HI, United States.

Henoch, M. & Chesky, K. (2000). Sound exposure levels experienced by a college jazz band ensemble: Comparison with OSHA risk criteria. Medical Problems of Performing Artists,15(1), 17-22. https://doi.org/10.21091/mppa.2000.1004

Michaudet, C., & Malaty, J. (2018). Cerumen impaction: Diagnosis and management. American Family Physician, 15(8), 525-529.

Miller, J. (1974). Effects of noise on people. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 56(3), 729-764. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.1903322

Miller V., Stewart M., & Lehman M. (2007) Noise exposure levels for student musicians. Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 22(4), 160-165.

Mirza, R., Kirchner, B., Dobie, R., & Crawford, J. (2018). ACOEM Task Force on Occupational Hearing Loss. Occupational noise-induced hearing loss. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 60(9), e498-e501.

National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD). (2019). Noise-induced hearing loss. https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/noise-induced-hearing-loss.

National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). (1998). Noise-induced hearing loss—Attitudes and behaviors of U.S. adults. Atlanta, NIOSH/CDC. http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/noise/abouthlp/nihlattitude.html

National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). (1998). Recommended exposure limit. In: Criteria for a Recommended Standard: Occupational Noise Exposure. https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/98-126/default.html

National Institutes of Health (NIH). (1990). Noise and hearing loss consensus conference. JAMA, 263(23): 3185-3190.

Occupational Health and Safety Administration (OSHA). (1983). Occupational noise exposure, standard 1910.95. Washington, DC. http://www.osha.gov/pls/oshaweb/owadisp.show_ document?p_id=9735&p_table=STANDARDS

Owens, D. (2004). Sound pressure levels experienced by the high school band director. Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 19(3), 109-115. https://doi.org/10.21091/mppa.2004.3019

Owens, D. (2008). Hearing loss: A primer for the performing arts. Medical Problems of Performing Artists 23(4), 147-154. https://doi.org/10.21091/mppa.2008.4031

Owens, D., & Schwartz, K. (2021). The incidence of hearing loss among university student musicians. National Band Association Journal, LXI(1), 40-47.

Phillips S., Shoemaker J., Mace, S., & Hodges, D. (2008). Environmental factors in susceptibility to noise-induced hearing loss in student musicians. Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 23(1), 20-28. https://doi.org/10.21091/mppa.2008.1005

Santucci M. (2009) Protecting musicians from hearing damage: A review of evidence-based research. Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 24(3), 103-107. https://doi.org/10.21091/mppa.2009.3023

Sataloff, R., & Sataloff, J. (1991). Hearing loss in musicians. In: Sataloff R., Brandfonbrener A.,

Lederman R., (Eds), Textbook of Performing Arts Medicine. Raven Press.

Sataloff, R., Sataloff, J., & Hawkshaw, M. (1997). Hearing loss in singers and other musicians.Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 12, 51-56.

Zeigler, M. (1997). An investigation of the prevalence of tinnitus in college music majors and nonmusic majors (Publication No. 9735829) [Doctoral dissertation, Florida State University]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.