Abstract

This article focuses on the two main types of minuets by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart—Tempo di Menuetto and Menuetto Allegretto—that appear in his symphonic works and in his pieces for dance accompaniment. Drawing on primary sources by Johann Joachim Quantz, Johann Philipp Kirnberger, Heinrich Christoph Koch, and Johann Gottlob Türk, I compare the tempo choices by selected conductors (Böhm 1962, Karajan 1971, Norrington 1991, Hogwood 1997, Harnoncourt 2014) in the third movement of Mozart’s Symphony no. 41 (K. 551, 1788). These five recordings represent a broad spectrum of tempi for Mozart’s Menuetto Allegretto movement in this symphony. After his time at Mannheim (1777-1778), Mozart moved away from the slower courtly dance to a faster type of minuet in his symphonic works. In their respective treatises and encyclopedias, contemporaries Quantz, Kirnberger, Koch, and Türk discuss the performance practice of eighteenth-century minuets played for dances and those for purely instrumental contexts. Rhythmic values defined the tempo of the minuet; the shorter the notes, the slower it was to be performed and vice versa. For conductors and musicians today, this distinction between Mozart’s Tempo di Menuetto and Menuetto Allegretto is important in determining a tempo that is informed by historical performance practice of the Classical period.

James A. Grymes

Tempo Choices in Mozart’s Minuets: Considerations from a Conductor’s Point of View

Tempo is more influential in shaping the style of a performance than almost any other interpretive decision. It determines the pulse, shape, and overall character of the piece. An innate understanding of tempo becomes even more important when we perform pieces written before Johann Nepomuk Maelzel (1772–1838) invented the metronome, such as works by Franz Joseph Haydn (1732–1809) and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791). In the absence of metronome markings, how do modern conductors performing works from the Classical period faithfully capture the composer’s intentions?

Solving questions about tempo requires extensive research and is fundamental to a conductor’s score study. German-American conductor Max Rudolf (1902–1995) included an entire chapter on “Choice of Tempo” in his book The grammar of conducting: a comprehensive guide to baton technique and interpretation (1995), in which he stressed that a conductor should take into account tempo considerations while preparing a score:

Conductors themselves, when studying an unfamiliar score, try right from the start to feel the music’s pulse, knowing that a well-chosen tempo will make a variety of musical details fall into place, which otherwise might turn out awkward and unconvincing. They also know that the choice of tempo can be marked by pitfalls. Tempo markings are vague, be they worded in Italian or the vernacular. Metronome indications do not always hit the mark, as admitted by composers when their markings are put to a test in performance. No wonder that Mozart called the choice of tempo not only the most essential, but the trickiest thing in music (Rudolf 1995, 359).

Rudolf added that the tempo should have some kind of flexibility, in other words a “tempo span” (Rudolf 1995, 361) that is within the range of 4 beats per minutes (bpm) above or below a given tempo. If the chosen tempo goes beyond 4bpm—according to Rudolf—it “would change the music’s character noticeably” (Rudolf 1995, 361).

An informal study of conducting curricula in the U.S. reveals that most conducting programs do not require training in historically informed performance practice. Instead, interpretive decisions such as tempo are often traditions passed down from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. When performing music of the Classical period, it is often insufficient to follow those canonic interpretations exclusively. Today, we have unprecedented access to scholarship that previous generations did not have; for example, we can easily read treatises that were for many years not available in English, nor even in print in their original languages.

There is a wealth of scholarship regarding historically informed performance practice, a movement that gathered momentum throughout the twentieth century and became a prominent musical force in the 1970s. Rethinking the performance of earlier music—especially works of the Renaissance, Baroque, and early Classical periods—became necessary as a result of the trend to romanticize music in performance, beginning with German conductor and composer Richard Wagner (1813–1883) and German conductor and composer Wilhelm Furtwängler (1886–1954). This romanticization of classical scores continued into the 1970s, with Karl Böhm (1894–1981), Herbert von Karajan (1908–1989), and Leonard Bernstein (1918–1990), among others. The size of the orchestras—particularly under Karajan—expanded well beyond the composers’ intentions. String players engaged in the ahistorical habit of adding vibrato, regardless of stylistic considerations related to the historical period, and tempi were often much slower than the markings indicated by the composer.

In light of recent research undertaken by scholars (Robbins Landon 1991, Butt 2002, Spitzer and Zaslaw 2005, and Grant 2014) and conductors (Harnoncourt 1985, Norrington 2007, and Bicket 2017) who have discovered testimonies, writings, and correspondence by contemporary witnesses, as well as other evidence as to how the music was performed during the composer’s time, it is evident that our understanding of performance practice has changed.

In his call for reconstructing the historical context in which Classical music was experienced by eighteenth-century listeners, American musicologist Neal Zaslaw states:

If we are to try to create an aesthetic experience of an eighteenth-century symphony analogous to the eighteenth century’s, we must first enquire what their [the listeners’] experience may have been. We cannot gain that knowledge without a clear understanding of the conditions of performance that were taken for granted then by the ablest musicians and most sophisticated audiences. Those conditions reveal themselves only incompletely through library research and ratiocination, for certain crucial aspects are likely to remain hidden until attempts are made to re-create those conditions in order to learn their implications (Zaslaw 1989, 445).

In exploring factors that conductors should consider when trying to recapture what the audiences of the eighteenth century experienced, this paper will examine the spirit and tempo at which minuets were performed in Mozart’s time.

In his research, Zaslaw has found that most contemporary musicians perform minuets too slowly, explaining, “the too-slow minuets with which many modern performances have been encumbered seem to have arisen from several causes: the general enlargement of orchestra and concert-halls, the Wagnerian slowing of classical-period tempos, the ‘powdered-wig’ image of the ancien régime in general and of the minuet in particular, and the mistaken idea that the minuet was danced on every crotchet [quarter note] rather than on every other one” (Zaslaw 1989, 497).

Table 1 Comparison of tempo choices in recordings of Mozart’s Symphony No. 41, mvt. 3, Menuetto Allegretto

|

Conductor |

Orchestra |

Year |

BPM |

|

Hogwood |

Academy of Ancient Music |

1997 |

ca. 208 |

|

Norrington |

London Classical Players |

1991 |

176 |

|

Harnoncourt |

Concentus Musicus Wien |

2014 |

ca. 170 |

|

Karajan |

Berlin Philharmonic |

1971 |

140 |

|

Böhm |

Berlin Philharmonic |

1962 |

ca. 130 |

A comparison of recordings of the Menuetto Allegretto movement of Mozart’s Symphony no. 41 in C Major, K 551 (see Table 1) supports Zaslaw’s claims. These five recordings by conductors Böhm, Karajan, Nikolaus Harnoncourt (1929–2016), Sir Roger Norrington (b. 1934), and Christopher Hogwood (1941–2014)1Karl Böhm, Mozart Symphony No. 41, Berlin Philharmonic (Deutsche Grammophon 4474162, 1962); Herbert von Karajan, Mozart Symphony No. 41, Berlin Philharmonic (EMI 5753773, 1971); Nikolaus Harnoncourt, Mozart Symphony No. 41, Concentus Musicus Wien (Sony 302635, 2014); Roger Norrington, Mozart Symphony No. 41, London Classical Players (EMI 7540902, 1991); Christopher Hogwood, Mozart Symphony No. 41, Academy of Ancient Music (L’oiseau Lyre 452496, 1997). span fifty-two years and represent a broad spectrum of considerably different tempi for Mozart’s minuet. While Böhm’s and Karajan’s recordings show a more cumbersome interpretation with a heavy and rich string sound and a great deal vibrato, Harnoncourt, Norrington, and Hogwood appear to be closer to Mozart’s intentions by using much faster tempi and more transparent sounds with less vibrato and forward motion.

The difference in choice of tempo among these recordings is eye-opening: there is a discrepancy of 78 bpm between Böhm and Hogwood. Hogwood’s recording—released thirty-five years after Böhm’s—reflects his focus on historically informed performance practice (HIP); those by Böhm and Karajan, on the other hand, reveal a Romantic approach, with a focus on a beautiful, rich and polished string sound. The recordings by Harnoncourt and Norrington recordings—issued twenty-three years apart from another; in 2014 and 1991, respectively—almost have an identical tempo and only differ by about 6 bpm.

Besides the tempo, other parameters such as phrasing, rhythm, texture, articulation, and dynamics differ drastically: Overall, the two slower recordings (Böhm and Karajan) give room for more sustained notes with a fast, wide, and constant vibrato. String players use heavier bow strokes while using the full length of the bow from the frog to the tip. The phrasing is predictable and the overall sonority doesn’t flow, resulting in a certain amount of monotony. The texture itself is pretty thick and not as crisp and transparent as the recordings by Harnoncourt, Norrington, and Hogwood. Those are noticeably faster, with long notes that taper and breathe. There is more dynamic contrast, and long phrases have more forward direction and shape.

Another obvious difference between the recordings is the instruments themselves, with the Harnoncourt, Norrington, and Hogwood recordings using period instruments. If baroque instruments (such as string instruments with a shorter fingerboard and gut strings) are not being used, modern instruments require a different technique by using more open strings. We should encourage string players to play without vibrato, and if possible, let them use baroque bows. If those are not available, ask them to play on the middle of the bow, and to avoid the tip and the frog.

Minuet vs. Scherzo

Questions regarding appropriate tempi from Mozart’s time are difficult to answer, as Maelzel’s metronome was not patented until 1815.2Johann Nepomuk Maelzel was a German inventor and engineer. See A. Wheelock Thayer, revised by D. Harvey, ‘Maelzel, Johann Nepomuk’, in Grove Music Online, Oxford Music Online https://doi.org/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.17414 Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827), who retroactively noted metronome markings for his first eight symphonies in 1817, developed the minuet form and changed it into a scherzo with a much faster tempo. The third movement of his Symphony no. 1 in C Major, op. 21 (1800) is titled “Menuetto—Allegro molto e vivace.” While this movement is still rooted in the eighteenth-century tradition and is labeled “Minuet,” it is, in fact, a scherzo (dotted half note equals 108 bpm). Beethoven himself noted the development of the genre by titling the third movement of his Symphony no. 2 in D Major, op. 36 (1802), written two years later, “Scherzo” (dotted half note equals 100 bpm).

The shift from the minuet to the scherzo had started twenty-one years earlier, in 1781 by Haydn. The minuet movements of his six string quartets, op. 33 “Russian” are replaced by scherzos. The second movement in op. 33, no. 1 is labeled “Scherzando—Allegro,” while nos. 2 to 6 bear either “Scherzo—Allegro,” “Scherzando—Allegretto,” or “Scherzo—Allegretto” markings. While Haydn retained the label “Minuet” in his symphonies, he started adding faster tempo markings at the beginning of his tenure as Kapellmeister at the court of Prince Paul Anton Esterhazy (1711–1762). Haydn wrote seventy-one symphonies between 1759 and 1779 (see Table 2a): eight of them do not contain a minuet movement (11%), forty-one of them (58%) bear the markings “Menuet,” “Minuet,” or “Minuetto,” while the minuets of the other twenty-two symphonies (31%) belong to the faster type, marked “Menuetto Allegretto,” “Menuet Allegro molto,” or simply “Allegro.” The minuet movements from the twenty symphonies that Haydn wrote in the 1780s (see Table 2b) are titled “Allegretto,” or “un poco allegretto,” except in four: Sinfonia No. 80; Sinfonia No. 82, “L’ours”; Sinfonia No. 87; and Sinfonia No. 90.

Table 2a. Haydn’s Symphonies from 1759 to 1779

|

Year |

Symphony |

Movement |

|

1759? |

Sinfonia No. 1 |

No minuet |

|

ca. 1757/61 |

Sinfonia No. 2 |

No minuet |

|

ca. 1759/60 |

Sinfonia No. 3 |

Menuet |

|

ca. 1757/61 |

Sinfonia No. 4 |

Finale: Tempo di Menuetto (last mvt.) |

|

ca. 1760 |

Sinfonia No. 5 |

Minuet |

|

1761? |

Sinfonia No. 6 "Le Matin" |

Menuet |

|

1761 |

Sinfonia No. 7 "Le Midi" |

Menuetto |

|

Sinfonia No. 8 "Le Soir" |

Menuetto |

|

|

1762? |

Sinfonia No. 9 |

Menuetto Allegretto |

|

ca. 1757/61 |

Sinfonia No. 10 |

No minuet |

|

ca. 1760 |

Sinfonia No. 11 |

Minuet |

|

1763 |

Sinfonia No. 12 |

No minuet |

|

Sinfonia No. 13 |

Menuet |

|

|

1761-1763? |

Sinfonia No. 14 |

Menuetto Allegretto (mvt. 3) |

|

ca. 1760 |

Sinfonia No. 15 |

Menuet (mvt. 2) |

|

ca. 1760/63 |

Sinfonia No. 16 |

No minuet |

|

ca. 1760/62 |

Sinfonia No. 17 |

No minuet |

|

ca. 1760 |

Sinfonia No. 18 |

Tempo di Menuet (last mvt.) |

|

ca. 1759/60 |

Sinfonia No. 19 |

No minuet |

|

ca. 1757/63 |

Sinfonia No. 20 |

Menuet |

|

1764 |

Sinfonia No. 21 |

Menuet |

|

Sinfonia No. 22 "The Philosopher" |

Menuetto |

|

|

Sinfonia No. 23 |

Menuet |

|

|

Sinfonia No. 24 |

Menuet |

|

|

ca. 1760/64 |

Sinfonia No. 25 |

Menuet (mvt. 2) |

|

ca. 1768 |

Sinfonia No. 26 |

Menuet (last mvt.) |

|

ca. 1760 |

Sinfonia No. 27 |

No minuet |

|

1765 |

Sinfonia No. 28 |

Menuet Allegro molto |

|

Sinfonia No. 29 |

Menuet Allegretto |

|

|

Sinfonia No. 30 "Alleluja" |

Finale: Tempo di Menuet piu tosto Allegretto |

|

|

1765 |

Sinfonia No. 31 "Horn Signal" |

Menuet |

|

ca. 1760 |

Sinfonia No. 32 |

Menuet (mvt. 2) |

|

ca. 1760 |

Sinfonia No. 33 |

Menuet |

|

ca. 1766 |

Sinfonia No. 34 |

Menuet Moderato |

|

1767 |

Sinfonia No. 35 |

Menuet un poco allegretto |

|

ca. 1761/65 |

Sinfonia No. 36 |

Menuetto |

|

ca. 1757/61 |

Sinfonia No. 37 |

Menuet |

|

ca. 1766-68 |

Sinfonia No. 38 "The Echo" |

Menuet Allegro |

|

ca. 1768 |

Sinfonia No. 39 "Tempesta di mare" |

Menuet |

|

1763 |

Sinfonia No. 40 |

Minuet |

|

1769 |

Sinfonia No. 41 |

Menuet |

|

1771 |

Sinfonia No. 42 |

Menuet Allegretto |

|

ca. 1771 |

Sinfonia No. 43 "Mercury" |

Menuetto |

|

ca. 1771 |

Sinfonia No. 44 "Mourning" |

Menuetto Allegretto (Canone in Diapason) |

|

1772 |

Sinfonia No. 45 "Farewell" |

Minuet Allegretto |

|

Sinfonia No. 46 |

Menuet Allegretto |

|

|

Sinfonia No. 47 "Palindrome" |

Menuet al Roverso |

|

|

ca. 1769 |

Sinfonia No. 48 "Maria Theresia" |

Menuet Allegretto |

|

1768 |

Sinfonia No. 49 "La Passione" |

Menuet |

|

1773 |

Sinfonia No. 50 |

Menuet |

|

ca. 1771/73 |

Sinfonia No. 51 |

Menuetto |

|

Sinfonia No. 52 |

Menuetto Allegretto |

|

|

ca. 1775/76 |

Sinfonia No. 53 "L'Impériale" |

Menuetto |

|

1774 |

Sinfonia No. 54 |

Minuet Allegretto |

|

Sinfonia No. 55 "Schoolmaster" |

Menuetto |

|

|

Sinfonia No. 56 |

Menuet |

|

|

Sinfonia No. 57 |

Minuet Allegretto |

|

|

ca. 1766/68 |

Sinfonia No. 58 |

Minuet alla zoppa un poco allegretto |

|

Sinfonia No. 59 "Fire" |

Menuetto |

|

|

1774 |

Sinfonia No. 60 "Il Distratto" |

Menuetto non troppo presto |

|

1776 |

Sinfonia No. 61 |

Menuet Allegretto |

|

1777? |

Sinfonia No. 63 "La Roxelane" |

Menuet Allegretto |

|

ca. 1773 |

Sinfonia No. 64 "Tempora mutantur" |

Menuet Allegretto |

|

ca. 1771/73 |

Sinfonia No. 65 |

Menuetto |

|

ca. 1778 |

Sinfonia No. 66 |

Menuetto |

|

ca. 1778 |

Sinfonia No. 67 |

Menuetto |

|

ca. 1778 |

Sinfonia No. 68 |

Menuetto (mvt. 2) |

|

ca. 1778 |

Sinfonia No. 69 "Laudon" |

Menuetto |

|

1779 |

Sinfonia No. 70 |

Menuet Allegretto |

|

ca. 1779/80 |

Sinfonia No. 71 |

Menuetto |

|

ca. 1763-1765 |

Sinfonia No. 72 |

Menuet |

Table 2b. Haydn’s Symphonies from the 1780s

|

Year |

Symphony |

Movement |

|

1781 |

Sinfonia No. 73 "La Chasse" |

Menuetto Allegretto |

|

ca. 1780 |

Sinfonia No. 74 |

Menuetto Allegretto |

|

ca. 1780 |

Sinfonia No. 75 |

Menuetto Allegretto |

|

1782 |

Sinfonia No. 76 |

Menuet Allegretto |

|

Sinfonia No. 77 |

Menuetto Allegro |

|

|

Sinfonia No. 78 |

Menuetto Allegretto |

|

|

ca. 1783/84 |

Sinfonia No. 79 |

Menuetto Allegretto |

|

ca. 1783/84 |

Sinfonia No. 80 |

Menuetto |

|

1783-1784 |

Sinfonia No. 81 |

Menuetto Allegretto |

|

1786 |

Sinfonia No. 82 "L'ours" |

Menuetto |

|

1785 |

Sinfonia No. 83 "La Poule" |

Menuet Allegretto |

|

1786 |

Sinfonia No. 84 |

Menuet Allegretto |

|

1785/86 |

Sinfonia No. 85 "La Reine" |

Menuetto Allegretto |

|

1786 |

Sinfonia No. 86 |

Menuet Allegretto |

|

1786 |

Sinfonia No. 87 |

Menuet |

|

ca. 1787 |

Sinfonia No. 88 |

Menuetto Allegretto |

|

1787 |

Sinfonia No. 89 |

Menuet Allegretto |

|

1788 |

Sinfonia No. 90 |

Menuet |

|

1788 |

Sinfonia No. 91 |

Menuet un poco Allegretto |

|

1789 |

Sinfonia No. 92 "Oxford" |

Menuet Allegretto |

The last twelve symphonies that Haydn wrote between 1791 and 1795 (see Table 2c), the so-called London Symphonies, reveal the continuing trend toward even faster minuet movements. While the tempo marking “Allegretto” in the minuet movements remain the same in the four symphonies nos. 96, 97, 99, and 101, Haydn increased the speed further and changed the markings to either “Allegro” or “Allegro molto” in nos. 93, 94, 98, 102, and 104. Three symphonies, nos. 95, 100, and 103 belong to the slower type of minuets, labeled “Minuet.”

Table 2c. Haydn’s London Symphonies

|

Year |

Symphony |

Movement |

|

1791 |

Sinfonia No. 93 |

Menuetto Allegro |

|

Sinfonia No. 94 "Surprise" |

Menuet Allegro molto |

|

|

Sinfonia No. 95 |

Menuet |

|

|

Sinfonia No. 96 "The miracle" |

Menuetto Allegretto |

|

|

1792 |

Sinfonia No. 97 |

Menuetto Allegretto |

|

Sinfonia No. 98 |

Menuet Allegro |

|

|

1793 |

Sinfonia No. 99 |

Menuet Allegretto |

|

1794 |

Sinfonia No. 100 "Military" |

Menuet Moderato |

|

Sinfonia No. 101 "The clock" |

Menuet Allegretto |

|

|

Sinfonia No. 102 |

Menuet Allegro |

|

|

1795 |

Sinfonia No. 103 "Drum roll" |

Menuet |

|

Sinfonia No. 104 "London" |

Menuet Allegro |

In Mozart’s case, questions concerning the tempi of his minuet movements have remained unanswered. Did Mozart move away from the courtly and dance-like minuets of his earlier music in favor of scherzos at the end of his life, as Haydn did in his string quartets and symphonies? Studying his instrumental oeuvre reveals that Mozart did indeed write faster minuet tempi later in his career. He distinguishes between minuets written for dance accompaniment—composed as individual, self-contained movements—and a faster type that appears in multi-movement instrumental works that have little to do with dance-type minuets.

These two types of dances were described by Mozart’s contemporaries Johann Joachim Quantz (1697–1773), Johann Philipp Kirnberger (1721–1783), Heinrich Christoph Koch (1749–1816), and Johann Gottlob Türk (1750–1813), who distinguished between the performance practice of two kinds of minuet tempos in the eighteenth century: Tempo di Menuetto and Menuetto Allegretto.

While in Bologna, Mozart wrote the following about the slower-paced Tempo di Menuetto to his sister Nannerl on March 24, 1770:

I intend shortly to send you a minuet that Herr Pick danced on the stage, and which everyone in Milan was dancing at the feste di ballo, only that you may see by it how slowly people dance. The minuet itself is beautiful. Of course it comes from Vienna, so no doubt it is either Teller’s or Starzer’s. It has a great many notes. Why? Because it is a theatrical minuet, which is in slow time. The Milan and Italian minuets, however, have a vast number of notes, and are slow and with a quantity of bars; for instance, the first part has sixteen, the second twenty, and even twenty-four (Anderson 1985, 121).

In this letter, Mozart refers to a theatrical minuet that contains many notes and is in slow time.

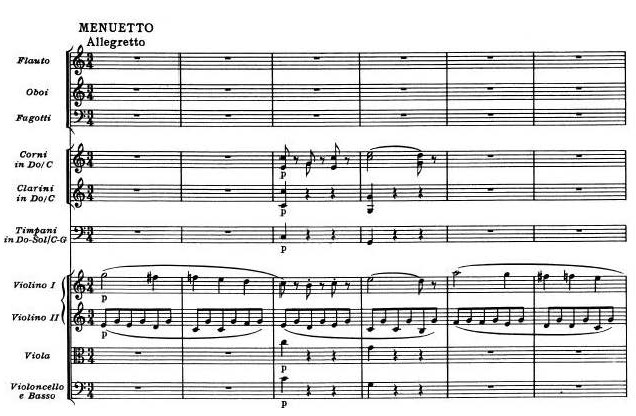

His Tempo di Menuetto from his String Quartet no. 5, in F major, K 158 (1772/73) is an example of this type of minuet (ex. 1).

In mm. 21–26 in the first violin part, we notice sixteenth-note figures; these suggest that the tempo cannot be too fast (ex. 2).

Later on in this movement, Mozart alternates between triplet eighth and dotted eighth notes followed by a thirty-second-note figure (mm. 29–33) (ex. 3).

Mozart was not the only composer of this style of minuet. In his treatise Versuch einer Anweisung die Flöte traversiere zu spielen (1752), German flutist, flute maker, and composer Johann Joachim Quantz (1697-1773) refers to the same type of minuet:

If in 3/4 time only eighth notes occur, in 3/8 only sixteenth [notes], or in 6/8 or 12/8 only eighth notes, the piece is in the fastest tempo. If, however, there are sixteenth notes or eighth-note triplets in 3/4 time, thirty-second notes or sixteenth-note triplets in 3/8 time … they are in the more moderate tempo, which must be played twice as slow as the former (Quantz 1966, 291).

Both Mozart and Quantz refer to theatrical minuets that contain sixteenth, thirty-second, and triplet notes. Therefore, the differentiation of rhythmic structure becomes important for determining the appropriate tempo. The more courtly, slower type of minuet for dance features a large number of sixteenth notes—another indication that the tempo should be courtly, dance-like, and felt in three.

In contrast, minuets containing only quarter and eighth notes correspond to the “fast dance tempo with a whole-bar accentuation” (Breidenstein 2019, 232). Quantz also mentions that minuets with eighth notes as the smallest note values should be of the fast type. However, if there are thirty-second notes or sixteenth-note triplets, it should be played in a moderate tempo and twice as slowly.

Further primary sources by composers and theorists Kirnberger, Koch, and Türk offer fascinating insights on how minuets were performed in the eighteenth century. Kirnberger wrote, “One should not think that the same dance has the same nuance in all nations. A trained ear will on the contrary easily distinguish a Viennese minuet from a Prague or Dresden one. The minuets from Dresden are the best, as the French ones are the worst” (Breidenstein 2019, 232). Koch also described two types of minuets, defining the minuet as a dance, characterized by a lovely and noble manner, that was typically played for openings of any kind of social dances.... For a long time, the minuet melodies, as well as those of other dances, were also used in the so-called suites and partitas. In parts of southern Germany during the middle of the previous century [eighteenth century], they also commonly began to appear in symphonies and three- and four-part sonatas, a habit that has been kept and has spread to almost everywhere. However, because these types of minuets are not intended for accompanying dances, both the rhythm of the minuet was accelerated and tempo considerations differed from the original minuet, and they were not tied to a certain number of measures or a similar rhythm; in addition, these minuets were played at a tempo much faster than they could be danced to. Haydn has exquisitely contributed to their various types in which the minuet now appears in his symphonies and types of sonatas (Koch 1802).3Translations from the German are my own, with assistance by Annett C. Richter and in consultation with existing English translations as available.

Lastly, Türk added, “The minuet, a well-known piece for dance of a noble and lovely character, in triple meter (more seldomly in 3/8 meter), is performed at a moderately fast and pleasing tempo, however without ornaments. In some regions, the minuets, when not performed for dances, are played much too fast” (Türk 1789).

Kirnberger, Koch, and Türk—three prominent witnesses and authors of primary sources of their time—all distinguish between the performance practice of minuets composed for dances and of minuets performed independently. Kirnberger’s comment on and preference for the Dresden minuets speak for his individual taste; apparently, he disliked the French ones. Koch, as theorist, violinist, and Kapellmeister, certainly had thorough knowledge of eighteenth-century performance practice, and his distinction between minuets for dance and those part of multi-movement instrumental works such as sonatas and symphonies remains crucial to be considered by conductors today. Furthermore, Türk, who also refers to the faster minuet type performed outside of dancing, observed that, in some regions, symphonic minuets were performed too rapidly. At the same time, he differentiated between the courtlier and dance-like tempo versus the faster minuet appearing in sonatas and symphonies.4The question of tempo also concerns another part of the minuet—the trio. In general, trios today tend to be taken at a speed slower than the minuet. Taking into account that the contemporary Hummel did not distinguish between these two, we should refrain from playing a minuet and trio at contrasting tempi. According to Zaslaw, ‘playing them [trios] more slowly than the minuets goes against the surely incorrect but virtually universal modern custom’ (N. Zaslaw, Mozart’s symphonies, 500).

A change from a minuet movement to some other form of symphonic middle movement was perhaps inevitable; with the shift and democratization of social life in Mozart’s time, minuets were becoming passé. According to Wye Jamison Allanbrook’s Rhythmic Gesture in Mozart, these “danceless” dances did not demand the stylistic gestures of the old aristocratic order. The new dance focused on a more democratic setting with looser and expandable floor patterns. Instead of correct expressive gestures, it was merely walking or running in order to traverse a given space (Yaffe 1984). According to Helmut Breidenstein, contredanses reached a peak of popularity in Mozart’s time and existed in a variety of forms. They constituted, together with the minuet and the German dances, the core of the ballroom dance repertoire, intended for a dance for group of pairs, with a lively, merry, even comical character (Breidenstein 2019, 244).

Mozart’s Minuets

To illustrate Mozart’s compositional development, I have created a timeline of Mozart’s works, written between 1768 and his death in 1791, that demonstrates the shift from a slower, courtly, dance-like minuet (Tempo di Menuetto) to a faster minuet (Menuetto Allegretto or Menuetto Allegro, respectively) (see table 3).

Table 3 Timetable of selected works by Mozart and places of their composition

|

Year |

Work |

Catalogue Number |

Movement |

Place |

|

1768 |

Bastien & Bastienne (No. 11, Aria) |

K 50 |

Tempo di Menuetto |

Vienna |

|

1772/73 |

String Quartet No. 3 |

K 156 |

Tempo di Menuetto |

Mailand |

|

|

String Quartet No. 5 |

K 158 |

Tempo di Menuetto |

Mailand |

|

1774 |

Symphony No. 28 in C |

K 200 |

Menuetto Allegretto |

Salzburg |

|

|

Bassoon Concerto in B-flat |

K 191 |

Tempo di Menuetto |

Salzburg |

|

1775 |

Violin Concerto No. 5 in A |

K 219 |

Rondeau: Tempo di Menuetto |

Salzburg |

|

1776 |

Divertimento à 3 in B-flat (pn, vl, vc) |

K 254 |

Tempo di Menuetto |

Salzburg |

|

|

Piano Concerto No. 7 in F |

K 242 |

Tempo di Menuetto |

Salzburg |

|

|

Piano Concerto No. 8 in C |

K 246 |

Tempo di Menuetto |

Salzburg |

|

1777 |

Divertimento in B-flat (2 ob, 2 bs, 2 hn) |

K 270 |

Menuetto Moderato |

Salzburg |

|

1778 |

Flute Concerto in G |

K 313 |

Rondo: Tempo di Menuetto |

Mannheim |

|

1779 |

Serenade No. 9 ‘Posthorn’ |

K 320 |

Menuetto Allegretto |

Salzburg |

|

|

String Quartet No. 17 ‘Hunt’ |

K 458 |

Menuetto Moderato |

Salzburg |

|

1780 |

3 Minuets |

K 363 |

No indication5For dance orchestra (without tempo indication). |

Salzburg |

|

1782 |

String Quartet No. 14 Op. 10 |

K 387 |

Menuetto Allegro |

Vienna |

|

1782/83 |

Piano Concerto No. 11 in F |

K 413 |

Tempo di Menuetto |

Vienna |

|

1783 |

String Quartet No. 15 |

K 421 |

Menuetto Allegretto |

Vienna |

|

|

String Quartet No. 16 The Viennese Sonatinas6Published in 1805 without K number. |

K 428 N/A |

Menuetto Allegro Menuetto Allegretto |

Vienna Vienna |

|

1784 |

Serenade No. 10 ‘Gran Partita’ |

K 361 |

Menuetto Allegretto |

Vienna |

|

|

5 Minuets |

K 461 |

No indication |

Vienna |

|

1785 |

String Quartet No. 15 ‘Dissonant’ |

K 465 |

Menuetto Allegro |

Vienna |

|

1786 |

String Quartet No. 20 ‘Hoffmeister’ |

K 499 |

Menuetto Allegretto |

Vienna |

|

1787 |

Serenade No. 13 ‘Eine kleine Nachtmusik’ |

K 525 |

Menuetto Allegretto |

Vienna |

|

1788 |

Divertimento (String Trio) in E-flat |

K 563 |

Menuetto Allegretto |

Vienna |

|

|

12 Minuets |

K 568 |

No indication |

Vienna |

|

|

Symphony No. 39 in E-flat |

K 543 |

Menuetto Allegretto |

Vienna |

|

|

Symphony No. 40 in G minor |

K 550 |

Menuetto Allegretto |

Vienna |

|

|

Symphony No. 41 in C ‘Jupiter’ |

K 551 |

Menuetto Allegretto |

Vienna |

|

1789 |

String Quartet No. 21 ‘Prussian’ |

K 575 |

Menuetto Allegretto7Senza replica. |

Vienna |

|

1789 |

Dances for Orchestra: 12 Minuets |

K 585 |

No indication |

Vienna |

|

1790 |

String Quartet No. 22 ‘Prussian’ |

K 589 |

Menuetto Moderato |

Vienna |

|

|

String Quartet No. 23 ‘Prussian’ |

K 590 |

Menuetto Allegretto |

Vienna |

|

1791 |

Dances for Orchestra: 12 Minuets |

K 599, 601, 6048K 599, K 601, and K 604 were published as one work. |

No indication |

Vienna |

The year 1778 marks a milestone and shows a turning point in Mozart’s work. While visiting Mannheim—a leading musical center at that time—he was exposed to a more “modern” style of orchestral playing, characterized by innovations by the Mannheim School. After his visit to Mannheim, Mozart started shifting away from the earlier Tempo di Menuetto to the faster Menuetto Allegretto (and Menuetto Allegro) tempo markings.9 One exception is his Piano Concerto no. 11, in F major, K 413/387a (1782/83) with the dance-like title Tempo di Menuetto for the final movement. At the same time, he continued to write a few slower minuets, labeled either Tempo di Menuetto or Menuetto without any tempo indication. In 1791, Mozart wrote twelve minuets (K 599, K 601, K 604), none of which bear a tempo designation. These works belong to the category of dance minuets in a courtly manner. In contrast, his two string quartets no. 22 (K 589) and no. 23 (K 590)—written in 1790—have the tempo indications of Menuetto Moderato and Menuetto Allegretto, respectively. Max Rudolf refers to the Menuetto Allegretto as follows:

Two minuet types alternate in Mozart’s works, one fairly fast, the other moderately slow. They also differ substantially in character and, therefore, must not be confused. Mozart was well aware of this distinction. Thus, an untold number of minuet movements are found in Mozart’s works, the large majority being of the fast type and usually bearing the tempo marking Allegretto. Still, Mozart continued all his life to compose slow minuets for which he used designations such as Tempo di menuetto or Menuetto moderato (Stern and Bleeker White 2001, 211–12).

Hummel’s metronome markings

In 1823, Mozart’s pupil, Johann Nepomuk Hummel (1778–1837) provided metronome markings for his piano arrangements of Mozart’s symphonies no. 35 in D Major, “Haffner” (K 385); no. 38 in D Major, “Prague” (K 504); no. 40 in G Minor (K 550); and no. 41 in C Major, “Jupiter” (K 551).10Hummel also arranged these symphonies for piano quartet. See Zaslaw, Mozart’s symphonies, 498. While Maelzel’s metronome was not invented in Mozart’s time, there are many primary sources referring to the invention of mechanical devices—the pocket watch and different types of chronometers, among others—to help determine the tempo and keep orchestras and dancers synchronized in rehearsals. From about 1786 to 1788, during the years when Mozart wrote his last three symphonies (K 543, K 550, and K 551), Hummel studied with Mozart (Zaslaw 1989, 498). According to Zaslaw, it is not clear whether Hummel, at a young age at the time, heard these works played under Mozart’s leadership. Even though Hummel absorbed Mozart’s musical style at that time, his arrangements for piano did not come about until more than thirty years later, and Hummel’s musical tastes had matured during this period. Nevertheless, his observations should not be overlooked. In Zaslaw’s words, “we dare not dismiss his [Hummel’s] tempos without due consideration” (Zaslaw 1989, 498).

The minuet movements of Mozart’s last two symphonies share the tempo indication Menuetto Allegretto, and Hummel marked them as follows: Menuetto Allegretto,11In Hummel’s piano solo arrangement it is labeled as ‘Menuetto Allegro.’ dotted half note equals 76 bpm (Symphony no. 40 in G Minor), and Menuetto Allegretto, dotted half note equals 88 bpm (Symphony no. 41; ex. 4). Hummel’s metronome markings indicate that these types of Mozart’s minuets were meant to be performed at a faster tempo and that they were no longer a courtly, dance-like minuet.

To compare Hummel’s nearly contemporaneous interpretation to a more modern one, we can turn to French pianist and conductor Jean-Pierre Marty (b. 1932), who in his book The Tempo Indications of Mozart (1988) writes the following about the Menuetto Allegretto: “this type of Allegretto 3/4 is also the tempo of many minuettos, such as those of [Mozart’s] last three symphonies. To all Allegretto minuettos a relation of 144/48 [referring to 144 bpm per quarter note or 48 bpm per dotted half note] appears suitable” (Marty 1988, 70). Marty’s argument represents the slower spectrum of tempo and therefore can be treated as an outlier.

Hummel metronomized the minuets as dotted half note equals 76 bpm and 88 bpm, respectively, yet Marty proposes that a speed of dotted half note equals 48 bpm is appropriate. This is far removed from what Hummel marked in his arrangements for piano solo, and Marty suggests a tempo too slow and one that is not distinct enough from Mozart’s courtly, dance-like minuet.

If we compare the two vastly different tempo propositions by Marty with 48 bpm per dotted half note and by Hummel with 88 bpm per dotted half note, we realize that Hummel’s is almost twice as fast as Marty’s, or, vice-versa, Marty’s twice as slow as Hummel’s. Taking these two tempi in quarter notes would result in 144 bpm and 264 bpm, respectively. Hummel’s choice might be appropriate for the piano solo arrangement; however, for an orchestral performance, it would be virtually impossible. Conversely, Marty’s 48 bpm would yield a rather slow and dragging rendition and would be too distant from the character of a symphonic minuet. As seen above, Mozart clearly differentiates between minuets for dancing and minuets for instrumental music, and that he, therefore, treats them independently.

Conclusion

In music from the Renaissance and Baroque, historically informed performance practice has been ever more present in modern performances and recordings. Yet the search concerning style, tempo, and interpretation of works from the Classical period merits further research. For a conductor to fulfill one’s duty as the “composer’s advocate,” it is paramount to undertake careful research and to not rely on customs nor one’s own preferences that cannot be traced back to the composer’s time. By doing so, we can present this music to audiences today as a reflection and our better understanding of the composer’s intentions and the performance practices of their time. Questions concerning tempo, especially with music written before Maelzel’s metronome require thorough research of primary sources as well as treatises from the respective time period. As Mozart wrote to his father Leopold in a letter in 1777, “the most necessary and hardest and most important thing in music is the tempo.”

[1] Karl Böhm, Mozart Symphony No. 41, Berlin Philharmonic (Deutsche Grammophon 4474162, 1962); Herbert von Karajan, Mozart Symphony No. 41, Berlin Philharmonic (EMI 5753773, 1971); Nikolaus Harnoncourt, Mozart Symphony No. 41, Concentus Musicus Wien (Sony 302635, 2014); Roger Norrington, Mozart Symphony No. 41, London Classical Players (EMI 7540902, 1991); Christopher Hogwood, Mozart Symphony No. 41, Academy of Ancient Music (L’oiseau Lyre 452496, 1997).

[2] Johann Nepomuk Maelzel was a German inventor and engineer. See A. Wheelock Thayer, revised by D. Harvey, ‘Maelzel, Johann Nepomuk’, in Grove Music Online, Oxford Music Online https://doi.org/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.17414.

[3] Translations from the German are my own, with assistance by Annett C. Richter and in consultation with existing English translations as available.

[4] The question of tempo also concerns another part of the minuet—the trio. In general, trios today tend to be taken at a speed slower than the minuet. Taking into account that the contemporary Hummel did not distinguish between these two, we should refrain from playing a minuet and trio at contrasting tempi. According to Zaslaw, ‘playing them [trios] more slowly than the minuets goes against the surely incorrect but virtually universal modern custom’ (N. Zaslaw, Mozart’s symphonies, 500).

[5] For dance orchestra (without tempo indication).

[6] Published in 1805 without K number.

[7] Senza replica.

[8] K 599, K 601, and K 604 were published as one work.

[9] One exception is his Piano Concerto no. 11, in F major, K 413/387a (1782/83) with the dance-like title Tempo di Menuetto for the final movement.

[10] Hummel also arranged these symphonies for piano quartet. See Zaslaw, Mozart’s symphonies, 498. While Maelzel’s metronome was not invented in Mozart’s time, there are many primary sources referring to the invention of mechanical devices—the pocket watch and different types of chronometers, among others—to help determine the tempo and keep orchestras and dancers synchronized in rehearsals.

[11] In Hummel’s piano solo arrangement it is labeled as ‘Menuetto Allegro.’

References

Allanbrock, Wye Jamison. 1983. Rhythmic Gesture in Mozart. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Anderson, Emily. 1985. The Letters of Mozart and His Family. London: Norton.

Breidenstein, Helmut. 2019. Mozart’s Tempo-System: A Handbook for Practice and Theory. Baden-Baden: Tectum Verlag.

Brown, Maurice J. E. “Starzer, Joseph (Johann Michael),” in Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. https://doi.org/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.26570.

Butt, John. 2002. Playing with History: The Historical Approach to Musical Performance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Derra De Moroda, Friderica. “Deller [Teller, Doeller, Toeller], Florian Johann (opera),” in Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. https://doi.org/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.O007004.

Grant, Roger Mathew. 2014. Beating Time and Measuring Music in the Early Modern Era. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Harnoncourt, Nikolaus. 1985, Musik als Klangrede: Wege zu einem neuen Musikverständnis Kassel: Bärenreiter.

Hummel, Johann Nepomuk. ca.1825. Grandes Symphonies de W. A. Mozart arrangées pour Piano. Mainz: Schott.

Yaffe, Martin D. 1984. On Understanding Mozart: A review of Rhythmic Gesture in Mozart. https://claremontreviewofbooks.com/on-understanding-mozart/

Koch, Heinrich Christoph. 1802. Musikalisches Lexicon. Frankfurt am Main: August Hermann dem Jünger.

Marty, Jean-Pierre. 1988. The Tempo Indications of Mozart. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Norrington, Roger. 2007. “Speed it up.” https://www.theguardian.com/books/2007/jul/21/music.

Quantz, Johann Joachim and Edward R. Reilly. 1966. On Playing the Flute. New York: Schirmer.

Raskauskas, Stephen. 2017. “How conductor Harry Bicket gets a modern orchestra to sound period perfect.” https://www.wfmt.com/2017/10/12/how-conductor-harry-bicket-gets-a-modern-orchestra-to-sound-period-perfect/.

Robbins Landon, H. C. and Howard Chandler. 1991. Mozart and Vienna. New York: Schirmer.

Rudolf, Max. 1995. The Grammar of Conducting: A Comprehensive Guide to Baton Technique and Interpretation. 3rd ed. New York: Prentice-Hall.

Spitzer, John and Neal Zaslaw. 2005. The Birth of the Orchestra: History of An Institution. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Stern, Michael and Hanny Bleeker White. 2001. Max Rudolf: A Musical Life: Writings and Letters. Hillsdale, New York: Pendragon.

Türk, Johann Gottlob. 1789. Klavierschule oder Anweisung zum Klavierspielen: für Lehrer und Lernende, mit kritischen Anmerkungen. Leipzig: Verf.

Wheelock Thayer, Alexander and Dixie Harvey. “Maelzel, Johann Nepomuk,” in Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. https://doi.org/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.17414.

Zaslaw, Neal. 1989. Mozart’s Symphonies: Context, Performance Practice, Reception.Oxford : Clarendon.