Abstract

This article explores data from the published literature, and a focus group, on recruitment and retention in the applied studio—topics, about which, applied faculty members have been reticent and private for decades. Authors shed light on historic and contemporary common practices, and problematize the implications of sustaining recruiting requirements as mandated by traditional music curricula and music departments within United States (U.S.) conservatories and universities. A review of the literature reveals few journal articles related to applied studio recruitment and retention and only four doctoral dissertations by researchers in the last 35 years. Our focus group was in the format of a panel discussion convened at a regional conference of the College Music Society. Six applied faculty members represented six institutions, public and private; participants taught in string, woodwind, brass, piano, voice, and composition studios. Our analysis of the scant published literature, and focus group comments, revealed many recruitment and retention practices that have remained common over the last 40 years or more and recurring inequity of resources, both within programs and between public and private institutions. Authors call for open dialogue and continued, shared research into equitable, productive, sustainable recruitment and retention methods in applied music studios within our conservatories and universities.

Donald Henriques

Recruitment and retention of talented students in the applied music studio is the major professional responsibility for applied faculty members within music schools and departments in higher education across the United States (U.S.). Successfully recruiting and retaining an applied studio may be the primary factor justifying the continued employment of untenured faculty members charged with applied studio teaching. As such, the success or failure of the applied studio may determine one’s very livelihood. In a tally of faculty members listed on websites of twenty top music schools and conservatories representing public and private institutions in various regions of the U.S., we found that the greatest number of instructors in the sample group were indeed the applied faculty members1Listed alphabetically: Berklee College of Music, Boston Conservatory, Cleveland Institute for Music, Colburn School Conservatory, Curtis Institute, Eastman School of Music, Florida State University, Indiana University, Juilliard Conservatory, Lawrence University, Manhattan School of Music, Mannes College, New England Conservatory, Oberlin Conservatory, San Francisco Conservatory of Music, University of Michigan, University of North Texas, University of North Texas, University of Southern California, and Vanderbilt University were identified as the best music schools of 2018 by Musicschoolcentral.com, Successfulstudent.org, and Thebestschools.org. However, compared to other aspects of music education and scholarship in institutions of higher education, relatively few published resources are available on recruitment and retention in the applied music studio, topics which influence the majority of music instructors in higher education (Jones, 1986).

Few applied music faculty members have written about their work in the American academy. Even fewer have written about how and why they build a studio over time--primarily recruiting and retaining music majors so essential to the continued functioning of most music departments and schools within higher education. There are limited articles related to instrumental and choral ensemble recruiting practices from beginning through university-level as well as private studio recruiting practices. A review of the literature reveals few journal articles related to institutional applied studios and only four doctoral dissertations by researchers in the last thirty-five years. This article analyzes published literature and focus group data on recruitment and retention in the applied studio and problematizes the implications of maintaining such recruiting requirements as mandated by traditional music curricula and music departments within U.S. conservatories and universities.

The relative scarcity of published material may be due to the work-intensive demands of the applied studio faculty members, who are often juggling various professional responsibilities such as improving their respective performance skills, establishing professional networks in the state, regional and national realms, staying current with performance traditions conveyed primarily through personal narrative, maintaining a presence in professional organizations, rehearsing with colleagues on and off-campus, and presenting guest masterclasses. Music schools and departments often recognize fresh interpretations of published or new works satisfying research/creative activity for applied faculty members, thus giving less weight to published scholarly research. Consequently, few applied teachers publish articles on recruitment and retention practices they have found to be successful. Indeed, College Music Symposium archives show a total of only two entries on recruitment: Rees, M. (1983). College Student Recruitment: The Importance of Faculty Participation, College Music Symposium, 23; and Waggoner, W. (1978). The Recruitment of College Musicians, College Music Symposium,18.

Mathias Wexler of the Crane School of Music in Potsdam provided an assessment of how applied studios function. “The extreme privacy of the studio teaching process has created a culture that reminds me of an ad I once saw in a magazine pumping the virtues of Las Vegas: ‘what happens in Vegas stays in Vegas.’ The studio has traditionally been a private, hidden locale, almost akin to a religious sanctuary” (Wexler, 2009, p. 1).

To stimulate dialogue and learn about successful recruitment and retention practices among colleagues, in 2012, Dwight Manning posted an inquiry on the International Double Reed Society Online Forum. “College applied faculty, what recruiting and retention practices have been productive for your double reed studios? Share your tips here.” After one month, there were 114 views of this posting but no responses. After one year, that same thread had accumulated 1,975 views and responses from only eleven other participants. At the writing of this paper, there were over 40,000 views, yet still only eleven other participants. The response rate (approx. three-tenths of one percent) may suggest that applied faculty members are keeping their productive practices confidential. This inquiry led to a literature review presented at the 2012 College Music Society (CMS) Northeastern Regional Conference: Recruitment and Retention in the Applied Studio: A Survey of Practices.

Literature Review

The undergraduate music curriculum typically requires applied study in every semester of four-year degree plans. As applied faculty members responsible for building and maintaining studios of capable performers and academic high achievers who would both satisfy the constant needs of the music school’s large ensembles and pass academic courses each semester, we found the perennial need to recruit new students to be one of the most challenging aspects of the job. Other authors have verified this challenging conundrum.

“Recruiting of music students is expected to become increasingly competitive among colleges offering music degrees during the next decade” (Brimmer, 1989, p. 5).

“Recruiting students may become increasingly difficult as more students select majors in business and technology fields and less in liberal arts” (Carlson, 1999, p. 12). “One of the greatest challenges music programme administrators face is that of recruiting students for their programmes” (Weinstein, 2009, p. 367).

As you consider these quotations from articles and dissertations, we draw your attention to the timeline of dates—three decades projecting increasing challenges. After years of working as applied faculty members, we have observed many of our top prospective students being recruited into various non-music degree programs. They often made decisions in favor of major financial aid based on academic achievement and promise. Over fifteen years ago, the Houston Chronicle printed an article on this phenomenon that has long frustrated applied music faculty members across the country. "More kids participate in music than any other high school extracurricular activity, and that tells you something right there," said Eric Martin, executive director for the Schaumburg, IL-based Bands of America, an educational group that staged events for more than 60,000 prep musicians every year."The members of the bands tend to be highly motivated kids and good students," he added."Even if music doesn't turn out to be their major, very often you see them going into other areas and doing well." Indeed, high school musicians as a group are so attractive that the National Association for College Admission Counseling, promoter of college fairs for students, organizes regional events strictly for music students. It has been doing this since 1991; music is the only specific academic discipline or activity the group breaks out for special treatment (Conklin, 2002, p. 12).

Common Recruiting Practices

Readers may already be familiar with common recruiting practices frequently mentioned in the limited available literature: campus visits (festivals, masterclasses, lessons), correspondence (letters and publications), phone calls, visits to high schools, referrals of school and private teachers, audition invitations, and financial aid.

Brimmer’s 1989 study of 150 music administrators in higher education revealed that relatively few differences were noted in the recruiting practices of music units in higher education throughout the United States, either by their geographic region or by their funding base. In 1982 Locke studied freshman music majors in Illinois. He found the factors that most influenced the college choice of potential music majors were (in order) overall reputation of the music department, reputation of the music faculty members, location of the college, variety of performing ensembles, and number of performing opportunities in those ensembles. Nearly forty years later, we have found that these are still major factors determining college choice for high school seniors throughout the country (See Findings).

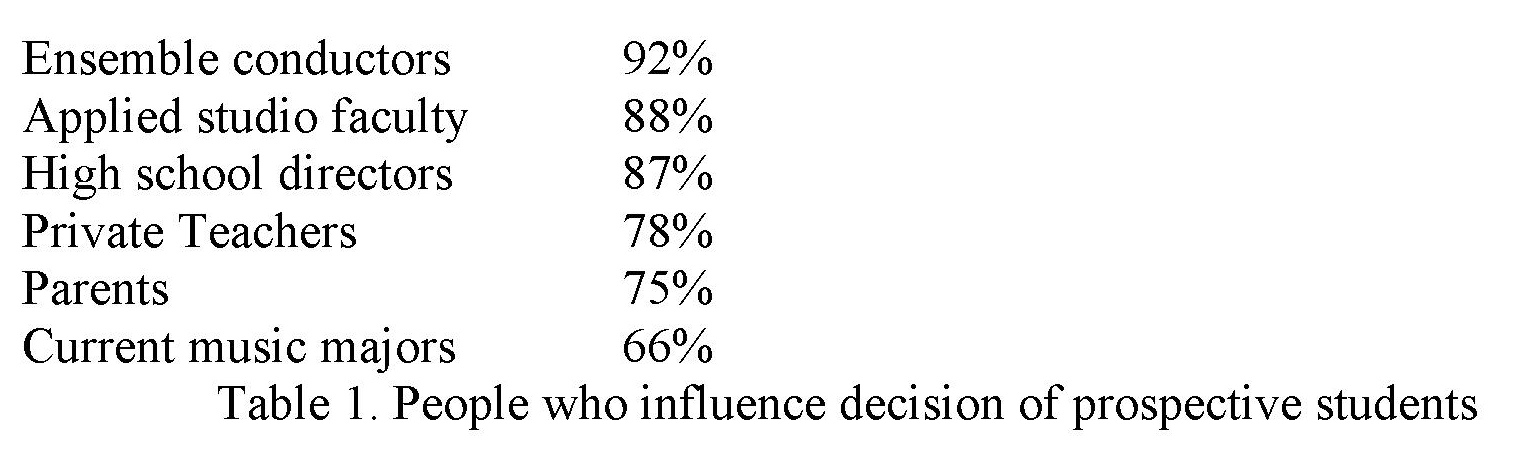

In 1999, Carlson’s research confirmed several widespread recruiting practices and their relative prevalence according to the perceptions of music department chairs and school directors in higher education. Most applied instructors realize that there are several other people who influence their recruiting efforts (Table 1).

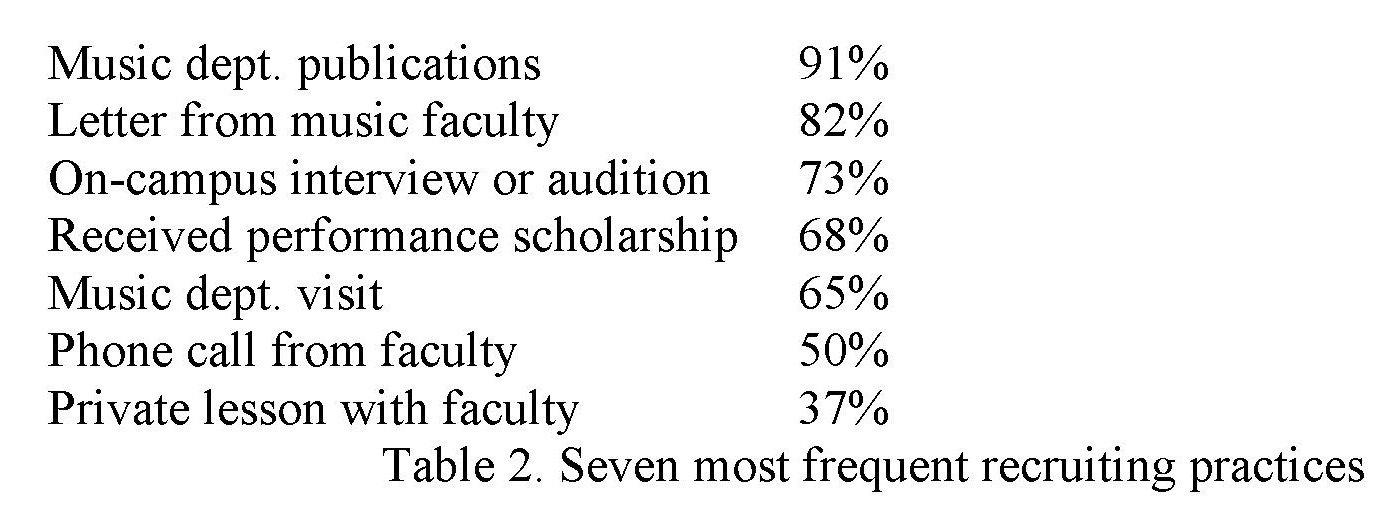

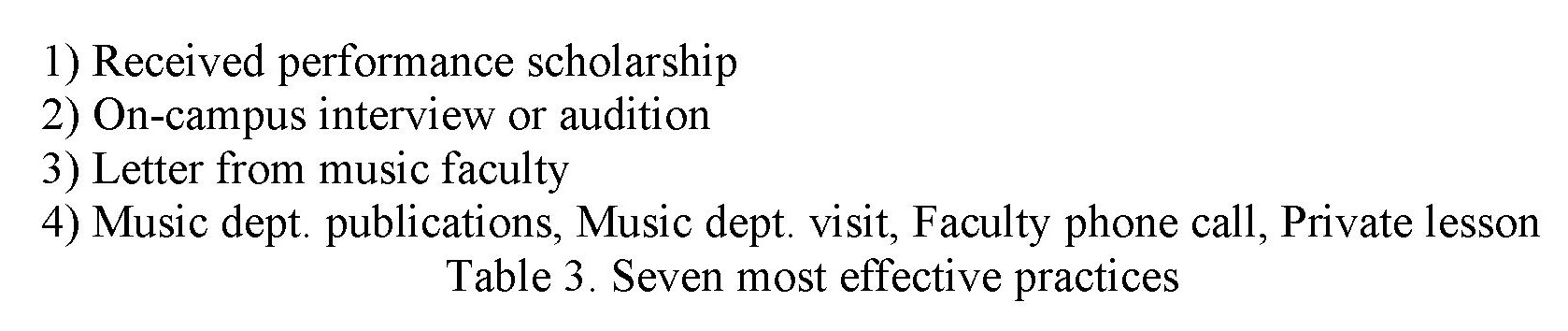

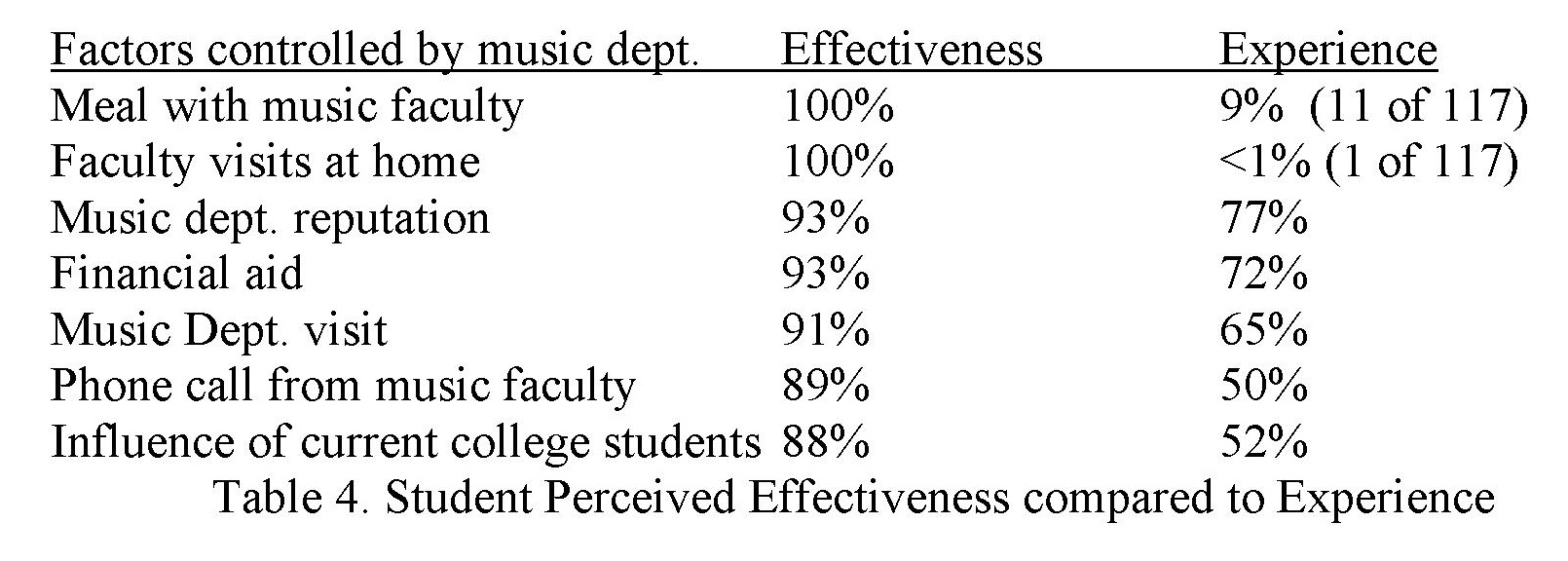

In 1996, Michael Straw studied the perspectives of 117 high school seniors who had participated in Missouri All-State Ensembles. He reported on how they perceived the effectiveness of various recruiting practices on their decision to participate in collegiate music departments. Following are the seven most frequent recruiting practices he found (Table 2), followed by a ranking of the most effective practices (Table 3). Participating students felt the most effective practices were (in order) scholarships, campus auditions and letters from faculty members. In terms of effectiveness (Table 3), the other practices listed were about equal in fourth place.

Alternative Approaches

There are a couple of sources suggesting approaches to recruitment of applied music students in U.S. higher education not commonly cited above. Brimmer suggested adopting balanced practices used in the field of marketing.

More marketing expertise is available for music student recruitment than is

currently being utilized. This includes strategies to identify the target market and

the development of a balanced marketing mix, i.e., strategies involving product,

price, place, and promotion. Most of the recruitment strategies observed relied

heavily upon promotional efforts and less on the other elements of a balanced

marketing mix (Brimmer, 1989, p. 80).

Weinstein’s 2009 article suggested another example from the field of management and advocates the benefits of implementing a comprehensive Total Quality Management (TQM) program. The core values, techniques, and tools embodied in the TQM approach provide an approach to quality management and process improvement. The article describes the principles of Total Quality Management and the efforts of a team of teachers and stakeholders at a mid-sized music department within a public university that applied this method to the problem of student recruiting.

Literature Review Implications

Implications of sustaining current curricular and institutional requirements by recruiting and retaining music majors in our studios appear less than optimistic (Fallin & Garrison, 2005; Frederickson, 2010; Parkes, 2010; Wexler, 2000, 2009; Williams, 2005). An article from the Chronicle of Higher Education stated:

Most students who graduate with degrees in music performance should not expect

to make their living playing music…Only a very few of the best students from the

top conservatories in the United States can realistically expect that their dreams

will be fulfilled…While music scholarship and music education have continued

unabated on the sidelines, music performance has been the most visible element of

postwar music programs. It also has allowed the schools to show off for the

university officials and state legislators who control the purse strings…As an

increasing number of music schools have sent more and more performance majors

out into the job market, it was only a matter of time before that market would be

glutted. The model was never sustainable (Wexler, 2000, pp. B6-B7).

A 2005 Music Educators Journal article “Answering NASM's Challenge: Are We All Pulling Together?” stated, “If every college had a full studio of applied majors for each applied teacher, the number of performance majors would grossly exceed the demand for performing positions” (Fallin & Garrison, 2005, p. 46). In the same year, Williams wrote:

It is a sad commentary that college music faculty are caught between two opposing realities. In order to justify salaries for tutorial instruction, applied music professors are pressured to recruit students to matriculate in performance degrees, even as that population of prospective students becomes reluctant (wisely) to pursue a career in music. Music faculty members find themselves trying to recruit students for music programs by telling them they can use a music degree as preparation for further study or work in other fields. It's a tough sell. (Williams, 2005, p. 72)

Applied pedagogy, i.e. studio teaching, in traditional music schools and departments often correlates with the content being taught—in other words conservative practices in a conservatory milieu. “College applied studio teaching has been examined, evaluated, and criticized in recent decades, but it has remained in place, unchanged in most ways due to the inherent ‘conserving’ nature of the music conservatory" (Parkes, 2010).

Research Questions

Seeking to illuminate obfuscated practices, we asked: What recruitment and retention practices have been productive, historically and contemporarily, for college applied music faculty members? Are institutionalized applied studio traditions and curricula sustainable in higher education music programs? Dwight Manning began pursuing these questions in 2012 and presented at the 2012 CMS Northeast Regional Conference--Recruitment and Retention in the Applied Studio: A Survey of Practices. Interest generated by that presentation led to a focus group in the form of a panel discussion at the 2013 CMS Northeast Regional Conference--Recruitment and Retention in the Applied Studio: A Panel Discussion.

Theoretical Framework

As applied music faculty members typically remain fully occupied maintaining professional skills, performing on and off campus, and engaging in service and outreach, theory and reflection may be pushed aside as a result. “Music educators are so involved in the practice of music that reflection on what we are doing is difficult and often contradicts our practice” (Lamb, 2010, p. 33). And even when on holiday or sabbatical, many applied faculty members may be inclined to continue traditional studio practices without question. To generate awareness and inquiry in the field, we approach this study through a critical lens problematizing institutionalized traditions and curricula. Critical theory has a rich and long tradition in the fields of philosophy, social theory, and social science and is oriented toward critiquing and improving social structures by revealing and questioning deeply held assumptions. “Critical theory can lead, then, to an entirely new point of view and to totally fresh approaches for understanding both the status of music education today and for addressing its many problems as a social project” (Regelski, 2005, p. 2).

Methodology

A literature review and a focus group traced how applied faculty members are positioning themselves in the often extremely private struggle to recruit and retain a viable applied studio. The original inquiry from 2012 and our literature review identified deficits in research publications related to recruitment and retention that have not been addressed in our field. The literature review revealed common and alternative practices in college studio recruitment and retention over a thirty-year period: 1980s to 2000s.

We wanted to explore what others were doing about recruitment and retention in applied music studios and brought together a focus group in the form of a panel discussion at our regional professional conference. The six panel members represented six institutions, public and private, within the Northeastern Region of the College Music Society; participants taught in string, woodwind, brass, piano, voice, and composition studios2Panelists/authors listed alphabetically: David Feurzeig, composition, University of Vermont; Donald George, voice, State University of New York at Potsdam; Maura Glennon, piano, Keene State University; Patrick Hoffman, trumpet, Delaware State University; Dwight Manning, oboe, Teachers College; Mihai Tetel, cello, Hartt School of Music.. We engaged in qualitative research practices: document review, analysis and synthesis, coding of focus group emergent themes (primary and subordinate), thematic analysis aligning data sets, and interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA)--an approach to qualitative research aiming to offer insights into how a given person, within a given context, makes sense of given phenomena. Typically, these phenomena relate to experiences of personal significance and the development of important relationships: detailed examinations of personal, lived experiences. IPA assesses phenomenological descriptions along with insightful interpretations, anchoring such interpretations in participants' accounts. The objective of IPA is to illustrate, inform, and master themes by firmly centering findings on quotations from participants. “If the researcher wants to study a group of individuals, he or she moves between important themes generated in the analysis and exemplifies them with individual narratives (how particular individuals tell their stories), comparing and contrasting them (i.e., showing similarities and differences)” (Pietkiewicz & Smith, 2014, p. 8).

Our 2013 panel discussion (lasting approximately 45 minutes) was audio recorded and transcribed, read, and reread (see Appendix for full transcript). Each panelist received a transcription of their recorded comments and had an opportunity to edit for accuracy of content and intent. These five data sets were then aggregated and analyzed by first engaging the NVivo qualitative data analysis software program and then by employing IPA while coding according to prominent emergent themes (patterns in data) relating to recruitment and retention in our personal lived experiences.

Findings

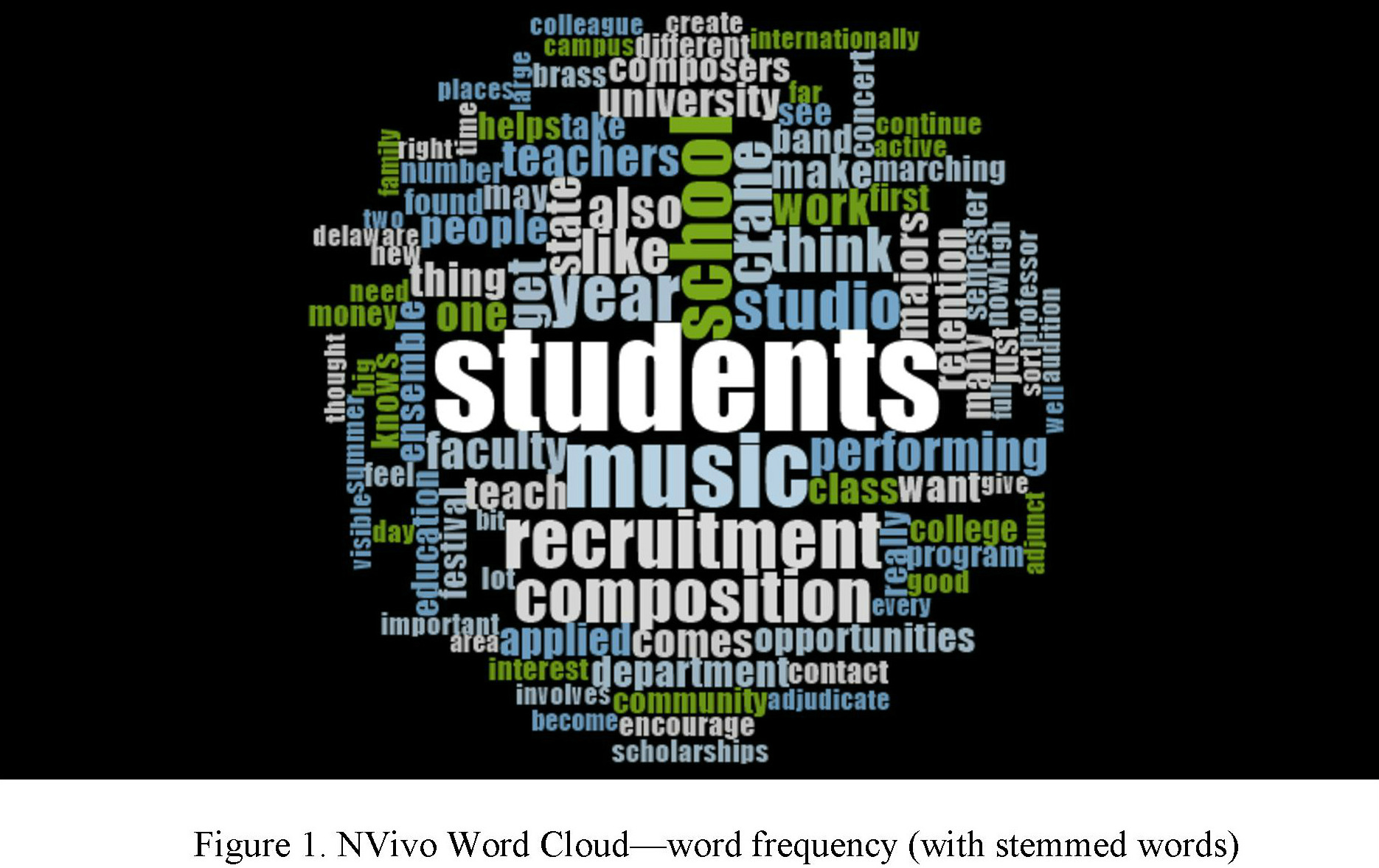

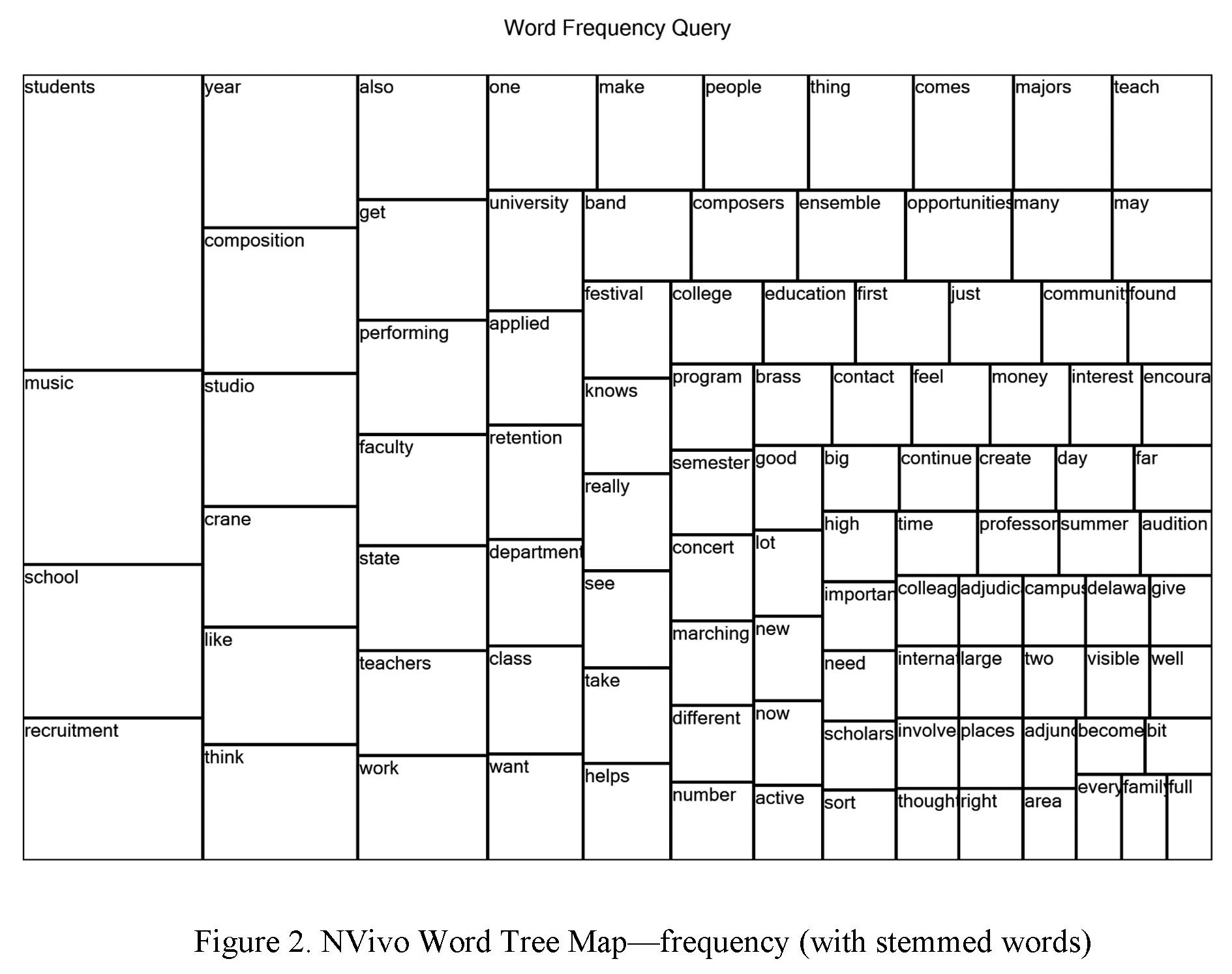

We began our analysis of focus group data by engaging NVivo software. Findings related to the frequency of spoken terminology (with stemmed words) follow. Figures 1 (Word Cloud), and 2 (Word Tree Map) reveal graphic representations of the frequency of words from the aggregated transcript of all six panelists.

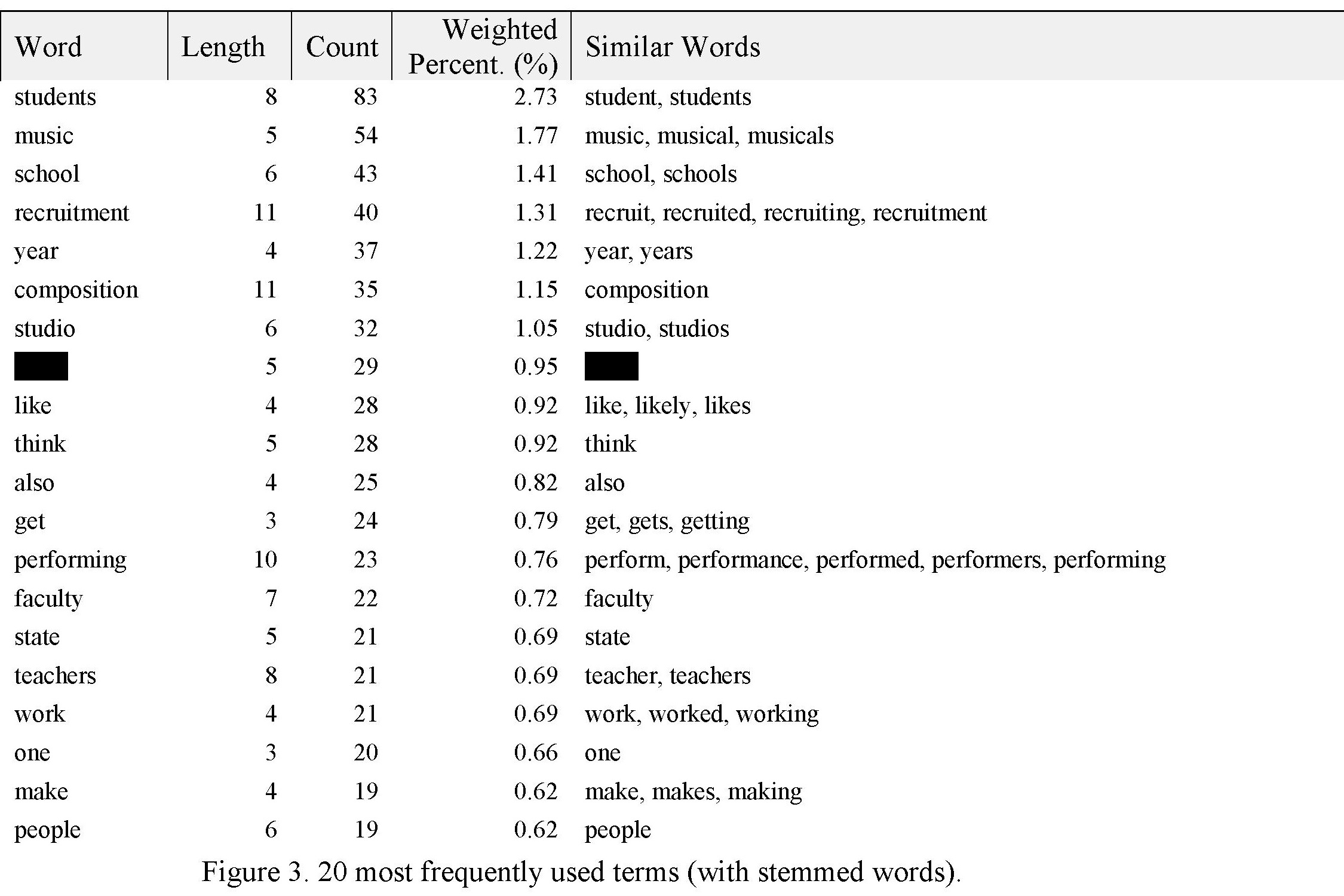

Figure 3 illustrates the 20 most frequently spoken words and their respective stems; e.g., the stem term perform also includes performance, performed, performers, performing. These terms appeared most frequently in the data set of all six panelists.

Findings related to the frequency of words solidly reflect concepts and topics relevant to recruitment and retention. Certain terms, i.e. Crane and composition, appeared frequently in the transcript but were restricted to only one panelist. Extracting those terms that were limited to one individual, we found that the most common stem words representing weighted percentages of 1.0 or higher (mentioned thirty-two or more times) were student, music, school, recruit, year, and studio. These words were most frequently mentioned by most panelists as idenfied by NVivo software. From this word list, we found clear, primary foci on students, then music.

Moving beyond words and their associated stems in order to assess the frequency of real practices and concerns that appeared across all panelists, we coded for emerging themes and engaged interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA). Common perspectives and practices of panelists extend well beyond simple word searches; for example, personal contact with prospective students may be represented by various individual terms such as e-mail, social media, telephone, concert, or visit.

Regarding recruitment of prospective students, we identified eight primary themes representing common experiences, practices or influences mentioned across panelists: 1) Personal contact; 2) Co-curricular activities; 3) Professional outreach; 4) Campus visits; 5) Financial aid; 6) Sense of family/community; 7) Performance opportunities; and 8) Institutional impact. Each is discussed in turn below.

As we read and reread, personal contact and interest in prospective students rose to the top of emergent themes. Social media, e-mail, telephone, networking on and off-campus, and mutual personal connections were mentioned as various ways to establish and maintain contact with the aim of recruitment. Since music students typically enroll in applied study all or most semesters of their respective degree programs, they see and become very familiar with applied faculty members and establish relationships that begin prior to matriculation and may extend well beyond graduation.

I established and maintained contact as early as possible with prospective students.

Before students enrolled in any university degree program, I got to know each one

through adjudicating and networking with other applied teachers, band

directors, students, or professional associations and tracking individual progress for

periods that ranged from several months to several years. (Manning)

I am constantly in contact with students from around the US and Germany where I

also reside, through email, Facebook, Twitter and through colleagues and

recommendations, and enjoy communicating with potential students, actively

recruiting them for my voice studio. (George)

Panelists spoke of several co-curricular activities such as traveling with student and faculty ensembles to perform for prospective students in their high schools, at festivals, or in prestigious venues. “To get the students out on the road and to make them feel like a band that's traveling, I think is just a great experience” (Hoffman).

Last year we performed the Verdi Requiem at Lincoln Center, this year Britten’s

War Requiem with Christof Perrick as guest conductor. These major events help in

both attracting voice students and also in retaining them, as Crane is full of

traditions, which become important emotional bonds for the students connecting

them to Crane. (George)

Several panelists spoke about participating in professional organizations, off-campus

performances and masterclasses, and about serving as adjudicators in their respective regions and beyond. Such professional outreach gains exposure in the field and access to prospective students and their teachers.

In my own studio, I adjudicate and perform. I’m a member of all my professional

organizations so I’m out there and I’m visible. I find that my adjudicating is one of

the most important outreaches that I can do as a piano teacher. (Glennon)

I do adjudication and also perform on their annual concert of student pieces, and

adjudicate All-State competitions and things like the BMI contest. (Feurzeig)

All panelists found it important to bring prospective students to their respective campuses for activities such as auditions, festivals, or summer programs.

So a couple of the things I’ve found very important, one of them is a festival for

your instrument. I think this is a fairly common occurrence at music schools. I took

the brass festival very seriously. When I started the brass festival, I didn’t realize

the implications of it... As I got into this, I realized hey this is an annual event, this

needs to continue happening here. (Hoffman)

Such events that draw students to campus can be mutually beneficial to one’s colleagues as well.

I began twenty-two years ago, an international summer music festival which has

guests from all over the world. I hired on faculty/professors from Eastman, Oberlin,

Juilliard, NEC and so forth... I draw a lot of students from my summer program

into my studio at the Hartt School and I help my colleagues as well because the

program is not just for cellists, but for other instruments as well. So, I wanted to

share this with you because I think that a summer program or festival can be an

important recruiting pipeline. (Tetel)

Financial aid, of course, plays an important role in recruiting students. Aid may be in the form of scholarships, service awards, and/or graduate assistantships drawn from a variety of institutional resources such as endowments, gifts, or institutional/departmental annual budgets. Our panelists represented a wide range of small and large, public and private institutions, so our lived-experience and interpretation of the phenomena of financial aid varied widely. Maura Glennon worked in a mid-size public liberal arts institution:

The other piece that we struggle with is that we have very little scholarship

money. In the Department of Music, we have three talent scholarships. We don’t

call them recruiting scholarships. So what it comes down to is, we can offer $4,500

scholarships to three students each year that they’re here, for four years. That’s

nothing; it doesn’t even make a dent in the tuition. So it’s very, very difficult for us

to recruit. (Glennon)

Toward the other end of the spectrum, Mihai Tetel had relocated from a Midwestern public university to an East Coast conservatory that is part of a larger private university.

And I was given $300,000 in scholarships to use for my students. There was no

problem recruiting when there was a better name for the school and a geographic

location which was wonderful, quite unique between New York and Boston, and

money was available for scholarships. (Tetel)

The sense of family or community is an aspect of recruitment mentioned by panelists but did not appear in our literature review. The development of such important personal relationships aligns well with IPA methodology. Such connections take time to develop, and many prospective students become aware of this aspect of an applied studio when visiting campus or interacting with the faculty member or with current or former students. Maura Glennon begins making connections when she first hears a student in the role of adjudicator at competitions or festivals.

It’s that personal comment that we can give to students and their teachers that they

can actually see on a piece of paper—how we want to teach, what we would focus

on, the work we would do together… It's a nice small department. They’re very

happy. It's a family. (Glennon)

Donald George concurs: “All of this contributes to the friendly family-like environment at Crane which I try to cultivate in my studio and which helps to both attract and retain students.” So does Mihai Tetel: “I found that… a family-like ambiance is very helpful”. Many themes that emerged from our panel discussion revealed tensions and inequities in the work of the applied faculty members. The personal connections with students, however, seems to be a positive aspect of recruitment and retention for all.

The sense of community and connection is perhaps one of the most gratifying

things about the work of applied faculty members. This level of mentoring may

continue for decades--before matriculation, beyond graduation, and into the

professional years. (Manning)

Prospective students are naturally interested in performance opportunities to develop their skills. Developing and maintaining performing skills are essential for students and faculty members alike.

I offer many performance opportunities in my studio and perform myself

frequently at Crane and internationally and organize and involve students and

faculty in special concerts, many with themes like The Muses in Music, The Gilded

Age, or this semester Comedy, Tonight …” (George)

David Feurzeig confirmed that performance opportunities are important in instrumental, vocal, and composition studios.

They all performed music before in their ensembles and perhaps solo with their

applied teacher before coming to college. But few of them have had the opportunity

to have their music performed. And if you say here’s the composition class concert

and you’re on it, and you have to have a piece ready by April so that we can

perform it in May, they feel fantastic. (Feurzeig)

A highly successful recruiter may encounter an internal struggle when a studio grows so large that incoming freshmen may be assigned to study with a graduate assistant or have limited positions in large and small ensembles. Dwight Manning referenced this delicate balance:

Later, during my years in Georgia, former students sent their own younger

students. As the studio grew in numbers and strength of performing skills, I found

that more high achieving students who were seeking challenges opted to join my

studio. The stronger performers often did not want to be a big fish in a small pond

their freshman year, as would be the case in a less successful studio. (Manning)

Such struggles and inequities refer to the issue of institutional prestige, mission, location, and cultural environment—all important factors in recruitment. Often an individual applied music professor has little or no influence on these matters, yet they are salient parts of the recruitment equation. Patrick Hoffman exemplified this in his experiences as a recruiter across institutions and regions:

I spent four years as instructor of trumpet and music theory at Minot State

University in Minot, North Dakota. So, in Minot we were dealing with a native

population which is very present there... And so you have to understand the region

you’re in when you think about recruiting for that region. And then, in stark

contrast to that where I’m teaching now is Delaware State University; even though

Dover is not necessarily a big city, were surrounded by Washington DC,

Philadelphia, Baltimore and, maybe a little bit farther, New York. So you don’t

have to go very far to be in a very metropolitan area. So the difference between

these two schools is stark. (Hoffman)

As we coded the aggregate data set, several subordinate recruitment themes, mentioned by fewer panelists, also emerged. These included media broadcasts, off-campus auditions, promoting music as a life skill regardless of college major, and recruiting students currently enrolled at the professor’s institution who might be inclined to change their major or concentration.

In some schools aspiring composition majors submit portfolios, and in other

places simply make their intention known and they just become composition

majors. I suppose this could be considered a form of poaching but I see it as an

extended form of retention. (Feurzeig)

Several recurring themes related to retention emerged. Most panelists concurred with Maura Glennon: “with retention we don’t have an issue.” Most agreed that recruitment and retention are interrelated. Patrick Hoffman commented: “recruiting and retention, these two Rs, are pretty much intertwined.” Identification with a community is also very important to retaining students. For example, panelists mentioned a sense of family, camaraderie, emotional bonds, each member of a studio feeling supported, and studio parties. “In terms of retention, I found that… a family-like ambiance is very helpful” (Tetel). Donald George highlighted the importance of performing opportunities: “I offer many performance opportunities in my studio and perform myself frequently at Crane and internationally and organize and involve students and faculty in special concerts.” Several agreed that presence at their respective institutions, allowing contact beyond weekly lessons, was significant. Mihai Tetel stated: “I am in the building six days a week. I like to be present, to be seen as a resource for my students who can see me not only when they have their hour lesson every week, but just about anytime they have a question.” Even when students are not retained until graduation, applied studios can still benefit as David Feurzeig mentioned “…if somebody transfers as a junior to Northwestern, I consider that a success. I consider that like an early graduate school placement, or something. It's the same kind of thing only a couple of years earlier. They remember us fondly.”

Synthesis and Implications

As we synthesized our review of literature and the analysis of panelists’ experiences, we found many congruent and some divergent practices and concerns. Certainly the published literature portrayed a sobering picture indeed.

Almost daily the media are reporting on the prospects of reduced budgets and

enrollments in colleges across the nation. If these forecasts are correct, many

college music faculties are facing rather unpleasant and uncertain futures. In the

face of these dire predictions, the profession must take action to maintain its status

and build for the future…Despite the dark clouds on the horizon of academia, there

are actions that music faculties can take to maintain the profession. (Waggoner, pp. 1-4)

In 2010, Frederickson published an article suggesting options for integrating each of the National Standards for Music Education into the private lesson studio. The applied studio teacher is often the only teacher who has individual, one-on-one experience with students throughout their undergraduate careers, and the convictions and teaching style of this studio professor could influence a novice music educator. College and conservatory music studios, therefore, offer a look at the extent to which and how students are given opportunities to make these connections and to develop thinking about the importance of a comprehensive approach to their own musical development.

The analysis of data from our focus group implied a generally optimistic perspective including successes and joys shared by applied studio faculty members—perhaps due to the live panel setting, or perhaps because all participants were successful applied faculty members naturally assuming their familiar role of recruiter. Camaraderie between students and their professor, a sense of family or community, were aspects of recruitment and retention mentioned by panelists, yet did not appear in our literature review. Each of the panelists’ experiences may be viewed as situated representations of broader phenomena across institutions and regions. Our analysis also revealed issues of inequity and many recruitment and retention practices that have been common over the last forty years or more. There is recurring inequity of resources both within programs and between public and private institutions.

Conclusion: Moving Beyond the Silence

Common practices mentioned in the published literature and our focus group included correspondence, financial aid, campus visits, phone calls with the aim of maintaining studio size, and balanced departmental ensembles. In the contemporary realm, contact and correspondence may take the form of e-mail or social media rather than written letters sent via postal mail, and we all depend on websites at our respective institutions. However, most other practices remain fixed within dated, long-standing institutional and curricular structures.

We wonder how long-standing curricular structures, and recruitment and retention practices may be reimagined or improved within rapidly changing social and educational systems in an increasingly global context, and how successful strategies may be applied across institutions and regions. Such inquiries truly need further dialogue and exposure, especially in light of the evident privacy and reticence of applied music faculty members. We conclude by calling for an exploration of institutional and curricular systems, continued and widely-shared research into equitable, productive, sustainable recruitment and retention methods in applied music studios.

Notes

1 Listed alphabetically: Berklee College of Music, Boston Conservatory, Cleveland Institute for Music, Colburn School Conservatory, Curtis Institute, Eastman School of Music, Florida State University, Indiana University, Juilliard Conservatory, Lawrence University, Manhattan School of Music, Mannes College, New England Conservatory, Oberlin Conservatory, San Francisco Conservatory of Music, University of Michigan, University of North Texas, University of North Texas, University of Southern California, and Vanderbilt University were identified as the best music schools of 2018 by Musicschoolcentral.com, Successfulstudent.org, and Thebestschools.org.

2 Panelists/authors listed alphabetically: David Feurzeig, composition, University of Vermont; Donald George, voice, State University of New York at Potsdam; Maura Glennon, piano, Keene State University; Patrick Hoffman, trumpet, Delaware State University; Dwight Manning, oboe, Teachers College; Mihai Tetel, cello, Hartt School of Music.

References

Abrahams, F. (2005). The application of critical pedagogy to music teaching and learning: A literature review. Update: Applications of Research in Music Education, 23(2),12-22. doi: 10.1177/87551233050230020103.

Brimmer, T. R. (1989). A perspective on the current state of college and university music student recruiting (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Ball State University, Muncie, IN.

Carlson, M. C. (1999). Undergraduate music student recruiting practices and strategies in public colleges and universities (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Missouri-Columbia, Columbia, MO.

Churchill, S. D. (1990). Considerations for teaching a phenomenological approach to psychological research. Journal of Phenomenological Psychology, 21(1), 46–67. doi: 10.1163/156916290x00119.

Conklin, M. (2002, Dec. 30). Competing for musicians; College recruiters on the lookout for high-school talent. The Houston Chronicle, p. 12.

Fallin, J. R., & Garrison, P. K. (2005). Answering NASM’s challenge: are we all pulling together. Music Educators Journal, 91, 45-49. doi: 10.2307/3400159.

Frederickson, M. L. (2010). The National Standards for Music Education: A transdisciplinary approach in the applied studio. Music Educators Journal, 97, 44. doi: 10.1177/0027432110387829.

Jones, J. (1986). Music performance faculty in higher education: their work and satisfaction. (Electronic Dissertation). Retrieved from https://etd.ohiolink.edu/

Kennell, R. (1992). Toward a theory of applied music instruction. The Quarterly Journal of Music Teaching and Learning, 3(2), 5-16.

Lamb, R. (2010). Music as sociocultural phenomenon: Interactions with music education. In H. F. Abeles & L. A. Custodero (Eds.), Critical issues in music education (23-38). New York: Oxford University Press.

Larkin, M., Watts, S., & Clifton, E. (2006). Giving voice and making sense in Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 102-120. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp062oa.

Locke, J. R. (1982). Influences on the college choice of freshman music majors in Illinois (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL.

Manning, D. (2012, Feb. 10). College studio recruitment and retention [Msg 1]. Message posted to https://www.idrs.org/forums/topic/college-studio-recruitment-and-retention/

Musicschoolcentral.com (2018). 10 of the best music schools in the US (2018 Edition). Retrieved from http://musicschoolcentral.com/10-best-music-schools-us-2018-edition/

Parkes, K. (2010). College applied faculty: The disjunction of performer, teacher, and educator. The College Music Symposium, 50, 65-76.

Pietkiewicz, I. & Smith, J.A. (2014). A practical guide to using Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis in qualitative research psychology. Psychological Journal, 20, 7-14. doi: 10.14691/cppj.20.1.7.

Pringle J., Drummond J., McLafferty E., & Hendry C. (2011). Interpretative phenomenological analysis: a discussion and critique. Nurse Researcher, 18(3), 20-24. doi: 10.7748/nr2011.04.18.3.20.c8459.

Rees, M. (1983). College student recruitment: The importance of faculty participation. College Music Symposium, 23. Retrieved from https://symposium.music.org/index.php/23/item/1939-college-student-recruitment-the-importance-of-faculty-participation

Regelski, T. (2005). Critical theory as a foundation for critical thinking in music education. Visions of Research in Music Education,6. Retrieved from http://www-usr.rider.edu/%7Evrme/v6n1/visions/Regelski%20Critical%20Theory%20as%20a%20Foundation.pdf

Smith, J.A., Jarman, M., & Osborne, M. (1999). Doing phenomenological analysis. In Murray, M., Chamberlain, K. (Eds), Qualitative health psychology: Theories and methods (pp. 218-240). London: Sage. doi: 10.4135/9781446217870.n14.

Smith, J. A., Flowers, P. & Larkin, M. (2009). Interpretative phenomenological analysis: Theory, method and research. London: Sage. doi: 10.1080/14780880903340091.

Straw, M. M. (1996). Missouri high school music students’ perception of recruitment techniques utilized by college and university music department (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Missouri-Columbia, Columbia, MO.

Successfulstodent.org (2018). The top 25 music programs in the US. Retrieved Oct. 15, 2018 from https://successfulstudent.org/top-25-music-programs-in-the-us/

Thebestmusicschools.org (2018). The 20 best music conservatories in the US. Retrieved from https://thebestschools.org/rankings/20-best-music-conservatories-u-s/

Waggoner, W. (1978). The recruitment of college musicians. College Music Symposium, 18, 1-4.

Weinstein, L. (2009). The application of a Total Quality Management approach to support student recruitment in schools of music. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 31(4), 367–377. doi: 10.1080/13600800903191997.

Williams, K. (2005). Reshaping dreams: "a life with music" or "a life in music"? The American Music Teacher, 55(2), 71-73.

Wexler, M. (2000). Teaching music students to make music for love, not for a living. The Chronicle of Higher Education, 47, B6-B7.

Wexler, M. (2009). Investigating the secret world of the studio: a performer discovers research. Musical Perspectives. Retrieved from http://www.musicalperspectives.com/Site/Archives.html.

APPENDIX

Focus group partial transcript, sequential order, March 16, 2013

(audience discussion not transcribed).

CMS Northeast Regional Conference, Keene State University

Dwight Manning, Teachers College, Director of Music Education and Oboe

Each of our six panel members will introduce themselves and discuss recruitment and retention from their own experiences in turn. To conclude, I’ll summarize emergent themes from our panel’s comments and open the session for discussion as time permits.

As our presider mentioned, I’m Dwight Manning from Teachers College, Columbia University. Previously, I taught applied oboe at the University of Georgia. Inspired by discussions following a paper I presented on applied studio recruitment and retention delivered at the 2012 Northeast Regional Conference in Fredonia last year, I assembled this panel to further the dialogue.

In my own practice of recruiting oboe students for 19 years at the University of Georgia, I found that personal contact, maturity and depth of the studio, and performing, teaching and financial aid opportunities to be the most effective recruiting tools. Retention was rarely an issue when there was a sense of community and continuing opportunity. I established and maintained contact as early as possible with prospective students. Before students enrolled in any university degree program, I got to know each one through adjudicating and networking with other applied teachers, band directors, students, or professional associations and tracking individual progress for periods that ranged from several months to several years. Unlike faculty in other university departments, applied faculty work individually with students on a weekly basis every semester of their music degree programs. The sense of community and connection is perhaps one of the most gratifying things about the work of applied faculty. This level of mentoring may continue for decades--before matriculation, beyond graduation, and into the professional years. I took full advantage of campus-based camps and festivals that drew students from the region.

I also founded a couple of chamber ensembles and took these performing groups to various venues thereby providing mutual benefit for enrolled students and also attracting the attention of prospective students. When personal travel and guest artist funds were scarce, I reached out to other oboe professors and set up exchange recitals and masterclasses. I had to pay for my own expenses when I traveled off-campus but I made contact with prospective students and later hosted guests on my home campus in exchange. Later, during my years in Georgia, former students sent their own younger students. As the studio grew in numbers and strength of performing skills, I found that more high achieving students who were seeking challenges opted to join my studio. The stronger performers often did not want to be a big fish in a small pond their freshman year as would be the case in a less successful studio. I also tracked those students who enrolled elsewhere. As they moved into their final year, I contacted them about graduate opportunities in my program. By the Spring of 2010, my last semester at the University of Georgia, I expected an oboe studio of 17 graduate and undergraduate music majors the following Fall.

As we open our panel to discussion, I’d also like to share a concern for your consideration. Studio size and ensemble needs may also influence recruitment efforts in applied studios within each department or school. Achieving a balance is a perennial challenge due to popularity of certain instruments, recruiting success of applied and ensemble faculty, and yes, even faculty politics. Instruments such as oboe, bassoon, horn and cello may be in short supply in large performing ensembles. Some years, depending on the administration, those studios may receive supplemental financial aid support. However, I have also observed scenarios in which recruiting involves a competition for resources. Some applied faculty may have grown their studios to the point that their applied students far outnumber ensemble needs. However, administrators may be reluctant to identify target numbers or reassign scholarship and graduate assistantships. I’m curious to hear comments on those topics from other perspectives.

Thank you, I’m Patrick Hoffman. I teach trumpet and brass ensemble at Delaware State University.

I work in a school of music that has between 50 and 100 majors. I’m not sure how that averages out as far as the many large music schools in the country but I think the situation is fairly typical and yet the circumstances, geography, history of the universities have a lot to do with how the music operation functions. First of all, I spent 4 years as instructor of trumpet and music theory at Minot State University in Minot, North Dakota. So, in Minot we were dealing with a native population which is very present there. You could say specifically native in the true sense of the word--a Native American population, as well as what I like to call a native North Dakota population. This is very different, I grew up in the Midwest, and the whole Dakotas mentality is quite a bit different. And so you have to understand the region you’re in when you think about recruiting for that region.

And then, in stark contrast to that where I’m teaching now is Delaware State University; even though Dover is not necessarily a big city, were surrounded by Washington DC, Philadelphia, Baltimore and, maybe a little bit farther, New York. So you don’t have to go very far to be in a very metropolitan area. So the difference between these two schools is stark. I’ve found it fascinating to see how I have to deal with the communities. That's one of the points I wanted to raise here which I’ve found compelling. For schools this size of between four and five thousand students, in my experience there is often, at the schools where I have taught, there has been a little bit of a perception problem. Because, when you are a small university, it seems very common to me that there is a perception that “Oh, that’s the in-town university” and it’s not a first choice for students. So you sort of have to fight against this image and this was very much on my mind when I considered recruiting. I thought the very first step that I had to take was to get the positive word out and create a buzz in the community. Which, interestingly enough, is the same thing as the topic here earlier—promoting yourself—we’re all trying to promote ourselves to a certain extent. But I felt like you have to win over the home crowd first. So that was really a mountain to climb for me in both places for me because you’re fighting against this image.

So a couple of the things I’ve found very important, one of them is a festival for your instrument. I think this is a fairly common occurrence at music schools. I took the brass festival very seriously. When I started the brass festival, I didn’t realize the implications of it. I thought it would be easy; I’d just hire in someone, a good friend of mine would come in and we’d do it for a couple of days. As I got into this, I realized Hey this is an annual event, this needs to continue happening here. In the working out of this brass festival I found out Wow, if I really want this thing to be successful I have to work at it year around. That plays into this philosophy of creating an image in your community because not only are you bringing in world-class artists, but in order to make your festival a success, you really have to work at it all year around. And the work involves getting out there into the community and being really good friends with all the band directors and all the students. The more years you do it, the more you can reach out. So what started out as a day or two festival that involves soloists and maybe your community orchestra evolved into an entire year of making sure everyone knows that the brass festival is this date.

The other aspect of this is that as the trumpet teacher I’ve been in charge of the brass ensembles. So my aim was to, not only use the brass ensemble in the way that it’s typically done, but take a look at all of the schools in the area where you’ve been working with these band directors and make sure that you’re taking your ensemble on the road.

That leads me to another point—about retention. When I was e-mailing back and forth with Dwight, one of my points was that recruiting and retention, these two Rs, are pretty much intertwined. For me it’s hard to separate one from the other because you’re sort of recruiting your own students all the time—you’re keeping them in your studio, you’re keeping them in the university. I always found that many of my teachers treated me like a professional from the day I showed up at the university. And I think that's what students need. They need to feel like, Hey, I am a student but also my teacher respects me. To a certain extent they see me as a colleague and not necessarily in a hierarchical relationship. That's why I think it’s important to get these students out on the road and get them performing. Obviously, we have fun doing things we do as teachers or we wouldn’t do them. To get the students out on the road and to make them feeling like a band that's traveling, I think is just a great experience.

Dwight mentioned the camaraderie that you get within a studio, you can get that within a brass department or on a larger scale within a music department. So, I think it’s important, get your students feeling like they are professional musicians. From that they can figure out Well, I like this or do I not like it.

This is a point I wanted to raise; this is a point of contention as I see it. I’m just going to put it out there. As I said there are similarities and differences in both of the teaching environment that I’ve been in. One of the biggest differences once I got to Delaware State is that, if you’re not familiar with the HBCU tradition in music, the marching band is a big thing—it's a really big thing. At Minot, we had no marching band. Interestingly enough, I created a marching band because I started a brass ensemble that served that function that was sort of a pep brass ensemble. When I got to Delaware State University the marching band tradition was already there and we have a marching band conductor who does a large amount of recruiting himself. I’d be interested to put this up for discussion among the people here or among our other panelists. I could do a separate session on the role of the marching band and its effect on the applied studio teacher. I thought I’d raise that because it has affected me in different ways in both of the places I taught and it has been a really big deal. I sort of pushed it away while I was at Minot State and at Delaware State it was sort of in my face. The stark contrast there is really interesting and I think everybody has their own marching band stories. I think the marching band has to be because of the athletic implications and because of the money we get. But also, it’s something that we struggle against it. I know as a student I always said Boy I’m glad I don’t have to be in the marching band. It has its uses and its recruitment possibilities, of course. Then you recruit people through the marching band and then you may say I really don’t want you to do that because in many ways it’s not that healthy. I just wanted to finish with that and maybe if we have time at the end we can talk about how it helps or hinders recruiting.

Hi. Donald George. I am a Professor of Voice at SUNY Potsdam, The Crane School of Music and also on the board for performance here at CMS.

I begin with a quote. ” Both musician and teacher must be combined in the successful teacher of music”. So wrote Julia Etta Crane (1855-1923), the founder of The Crane School of Music, over 125 years ago. This erudite and visionary musician and educator also said that the best music teacher “sees the development of the character of the pupils as his first concern.” In this 125th anniversary year of The Crane School of Music at SUNY Potsdam, interest in the life and mission of this innovator in music education is particularly highlighted. Her plans, she said, “will give music its right place in the general scheme of education.” Julia Crane’s philosophy of music education permeates my studio even today, and indeed our School of Music, and I believe plays an important role in both my recruitment and retention of students and the general recruitment and retention in The Crane School of Music overall. Retention and Recruitment are thus intrinsically intertwined.

Julia Crane stressed having a happy class in her manuals. As she said “A happy quality of tone can only come from a happy ear.” We pride ourselves on continuing the goals of Julia Crane and our alumni Renee Fleming, Stephanie Blythe, Dimitri Pitas, Lisa Vroman and others attest to the fact that we still educate world class singers and teachers. In our recruitment efforts, we have "free advertising" so to speak by the simple fact that these vocal stars from Crane attract students nationally and internationally to audition at Crane. Fleming has mentioned the school in her autobiography, this semester the opera ensemble and soloists are performing in in New York City with Blythe and Vroman (of Phantom of the Opera) which increases the exposure for Crane. Our Candlelight Concert is also broadcast each year by PBS which also increases the exposure.

In addition, we hold auditions in different locations in the state of New York: Long Island, Albany and Rochester. I am constantly in contact with students from around the U.S. and Germany where I also reside, through email, Facebook, Twitter and through colleagues and recommendations, and enjoy communicating with potential students, actively recruiting them for my voice studio.

There are several events at Crane which help in recruitment for my studio. We hold one audition day in Crane each semester, which is proceeded by a Faculty Gala the night before and short concerts and events during the day of auditions. Crane also has a commons area, which serves food, and is open during the Auditions Day and which forms a community center during the rest of the semester helping to create the “happy ear(s)” that Julia Crane found so necessary.

We also have the good fortune to have several endowments and thus, the ability to give various scholarships. Recently, the Loughheed family has endowed a Spring Festival, which culminates in an orchestral/choral concert. Last year we performed the Verdi Requiem at Lincoln Center, this year Britten’s War Requiem with Christof Perrick as guest conductor. These major events help in both attracting voice students and also in retaining them, as Crane is full of traditions, which become important emotional bonds for the students connecting them to Crane.

In addition, we in the voice department, have master classes each semester with a major artist. For example, Lawrence Brownlee and Gerhard Siegel from the Met are performing and giving Master Classes this semester, as are Martin Katz and Libby Larsen, which also helps in both our recruitment and retention.

I offer many performance opportunities in my studio and perform myself frequently at Crane and internationally and organize and involve students and faculty in special concerts, many with themes like The Muses in Music, The Gilded Age, or this semester Comedy, Tonight ….Again, this helps to create an important sense of community, an “ensemble” if you will, and a camaraderie in the studio that contributes particularly to retention.

Vocal students (some 160 in number in education, performance and business) know that they will have ample opportunity to perform in opera, musical, choir and concert. Vocal education students are also involved in the operas, musicals and conducting the choirs and vocal groups. This group of students is constantly replenished by new and striving students eager to come to the family environment of Crane and the chance to work with the likes of a Fleming or a Blythe. In fact, Blythe has started the Fall Island Vocal Arts Seminar as a summer program at Crane. We also have CYM (Crane Youth Music) in the summers where high school students come to “camp” at Crane and take lessons by studying with Crane professors. Most of these students then return to Crane as students often choosing the professor they worked with in the summer. This all contributes to a vital and active vocal environment at Crane, that my studio readily takes part in. Surveys have shown that personal contact with faculty, campus visits, and advice from high school music teachers are more important factors for students choosing a school than other factors. At Crane we encourage these contacts.

I also hold studio parties each semester which helps in the camaraderie and memories, encourage music research with our Title III program, with which we are attending NCUR 2013 in La Crosse WI, and Kilmer Apprenticeships, which have monetary rewards and have started a student CMS chapter as a few examples which keep my studio active and creates an atmosphere of special projects to look forward to each year.

Julia Crane said that “Music becomes a means for learning the thoughts and emotions of the great masters of poetry and art, and ultimately a beautiful expression of one’s own best thoughts and feelings: (When we can achieve this goal) …then may we say truly that there are teachers who have solved the problem of education. “

All of this contributes to the friendly “family-like” environment at Crane which I try to cultivate in my studio and which helps to both attract and retain students. Thank you.

Hi I’m Maura Glennon. I’m Professor of Music and Chair of the department here at Keene State College.

Keene State is a similar to Delaware State, a school about 5,000 students in size. It's a public a liberal arts institution. The history lies in its past as a Teachers College, that’s how it was founded. So our music program here is structured primarily on music education. We also average about 80 to 100 majors a year. Our class sizes are about 25 to 30 in the incoming classes. They come from all over New England, it’s not primarily New Hampshire. The most interesting fact we face here is that we have a huge number of first generation college students—close to 47% is what we average. So these are students whose families are not used to paying for college. So when they come and they check out our school, they say “I can’t afford a $27,000 fee for out-of-state tuition,” and they don’t come.

The other piece that we struggle with is that we have very little scholarship money. In the Department of Music, we have three talent scholarships. We don’t call them recruiting scholarships. So what it comes down to is, we can offer $4,500 scholarships to three students each year that they’re here, for four years. That’s nothing; it doesn’t even make a dent in the tuition. So it’s very, very difficult for us to recruit. Now those students can qualify, clearly, for financial aid, they can take loans. We don’t like to talk about money here. So this is the case. We get the students here; we have huge recruitment activity; we’re really active with the faculty who go out there and do the work. We have 10 full-time faculty and 20 adjunct. Eight of our full-time faculty teach applied music and at least 10 or 12 of our adjunct faculty teach applied music. Now here is the burden. Our full-time faculty are required to do this work; they’re required to go out and recruit and be seen out in the world and let the students see them so they can recognize Keene State College and come audition. Our adjunct faculty don’t have the support to be asked to do that. And this is what I struggle with as the department chair. I can’t ask my adjunct faculty, who are paid meager fees to teach their classes to then go out and travel with their students. I can pay them small honoraria but I can’t pay them what they deserve to be paid. And I think that's what we struggle with in recruitment. So there are other full-time faculty who do this. We have one of our choral directors who takes our chamber singers on tours through New England. Our guitar teacher takes his guitar orchestra to Boston every year, to be visible out there. Most of our faculty do perform; our adjunct, quite regularly, throughout the year and in the summer. We all do all these festival so we can be visible and we can be seen.

In my own studio, I adjudicate and perform. I’m a member of all my professional organizations so I’m out there and I’m visible. I find that my adjudicating is one of the most important outreaches that I can do as a piano teacher. It’s that personal comment that we can give to students and their teachers that they can actually see on a piece of paper—how we want to teach, what we would focus on, the work we would do together. So I feel that’s how I have increased my piano studio since I’ve been here. I started at Keene in 1998 and when I came I had no piano majors. My highest studio numbers were about ten; right now I have six. So it covers between five and six and for a department of 100 majors, that's not bad, I’m satisfied. The level of students has definitely increased; the abilities, I think because of my presence in the community. So I think the work that I’m doing in my studio is good. The struggle is truly about money. This is a state school; it’s in New Hampshire. We live free or die (laughter). We don’t have a lot of money and our school doesn’t get the funding to solve this. We don’t have endowments; we don’t have a lot of big donors. When it comes down to it, students who get here to audition like us and want to come here, we get the positive feedback; but they choose a school where they get more money.

Now with retention we don’t have an issue. I don't think we do; we get the students here and they like it here. It's a nice small department. They’re very happy. It's a family. It’s comfortable. They might change degree programs within the school but they stay and they’re successful. And they have a high placement rate after graduation, particularly the teachers. So I think it comes down to money; how we treat our adjuncts, and what money we give our students.

Mihai Tetel, Hartt School of Music, Cello.

Good morning. My first thought was about exactly what my colleague from Delaware said. I experienced two different situations in my two college jobs I had so far. I moved from a small town—Muncie, IN where I taught at Ball State University for five years, in the middle of nowhere. I had between 8 and 11 cello students, which I got through a great deal of struggle to recruit in local schools. Again, I think the image is a problem because that school was not seen as high ranking in the world of music education. So after five years, I was able to get the job at the Hartt School. In my first year, I had 29 cello students. I was given $300,000 in scholarships to use for my students. Recruiting for a private institution that has a national and international reputation was much easier, compared to recruiting for a public institution where scholarship money was very limited. There was no problem recruiting when there was a better name for the school and a geographic location which was wonderful, quite unique between New York and Boston, and money was available for scholarships. So, it made it, obviously, a lot easier. Now, to maintain that number, I had to rely on an enterprise that I began 22 years ago which helped me out to get those two jobs in Indiana and at the Hartt School.

I began 22 years ago an international summer music festival which attracts students from all over the world. I hire faculty from prestigious institutions such as Eastman, Oberlin, Juilliard, NEC and so forth... I draw a lot of students from my summer program into my studio at the Hartt School and help my colleagues as well, because the program is not just for cellists but for other instruments as well. So, I wanted to share this with you because I think that a summer program or festival can be an important recruiting pipeline that a summer festival can produce, that person not only would not only have a strong studio but would make it attractive for institutions to look at this professor as a good candidate for their faculty. So, that was and is one of the best recruiting tools I could find and I continue to do it. Like my colleague said, it is a year-round job. I work 11 months to produce a one-month summer festival but it becomes, obviously, a 12-month-a year involvement in music and I also do it because I enjoy it.

In terms of retention, I found that, like my colleague from the Crane School of Music, a family-like ambiance is very helpful. I am in the building six days a week. I like to be present, to be seen as a resource for my students who can see me not only when they have their hour lesson every week but just about anytime they have a question. I want them to know, that I’m in the building ready to answer their questions. Also, it helps to have several other classes so I can expand my contact with them. I have a weekly cello studio class. I invite guest speakers to come and work with my students. I have a technique class, orchestral excerpts class so can I keep them motivated and bombarded with information. So, I try to not limit my contact with them to one hour a week. When they know that they get so much, they tend to stay. In fact, I never had one student want to leave because they feel that they get quite a bit of instruction and contact time with me by being at the Hartt School. Those are my thoughts on retention and recruitment.

David Feurzeig, University of Vermont, composition

I’m a little bit of an odd fit on this panel. I don’t know how many of you normally think of composition as an applied area. Of course it is, but it’s obviously not performance. There are a number of differences, some similarities to talk about, but some very different things about our situation and recruitment and retention. For one thing, from the faculty perspective, it’s the rule rather than the exception that composition teaching is a fraction, often less than half, of a composition professor’s load. I taught at a small liberal arts college in Kentucky with about 20 music majors, and a large Midwestern state school of music with about 400 majors, and now I’m in-between at a medium sized department at what’s nominally a Research level I state university, but in a department that’s exclusively undergraduate with a high proportion of music education majors. In none of those schools did I ever have what composers call a “straight composition job” which is kind of the holy grail of composition teaching activity for some aspiring composers. I think there are a few dozen institutions, and a few dozen individuals in the country who have them. There aren’t many composers, you’ve likely heard of most of them, who teach exclusively composition. Most of us teach a lot of theory and who knows what else. That’s happening, of course, more and more, and it’s the norm for composers. So it’s sort of a two-edged sword: on the one hand I have experienced little or no pressure to increase the number of composition students, or to make sure we have so many composition incoming freshmen, which is great. I don’t have that pressure. On the other hand, that makes composition a luxury. And nobody cares, unless I decide to make it an issue, whether or not we have composition instruction at all. I think that a department without student composers is a dead or dying department; it’s boring! When students are writing music and playing music of their peers and colleagues it’s immediately exciting and it really brings the department to another level. But if it doesn’t happen nobody misses it: it’s not like we can’t run wind ensemble this year because we don’t have any composers. It doesn’t work that way, right? So, actually I’ve had to advocate and say that we need to teach composition every semester. And they say, “well, what do you mean? You don’t have the students needing to take it.” So it often begins as service; I’ll teach a few lessons. And then we reach a critical mass and they see now I have these ten people and I can teach composition as a class we can offer every semester. This is wonderful, but then people say “so what?” We still have to cover all the classes I had to teach before in the theory area. So there’s that tension, where it’s a luxury not to have to worry about student population, but then it’s something we have to advocate offering.

The other thing about composition recruitment, which goes along with the first thing, is that just as very few schools have the very prestigious, internationally famous composition instructor, likewise there are very few schools that really admit many freshmen composition majors, as such. They may allow the possibility but many, many schools have most of their composition students, I call it, “internally recruited”. They are current freshmen or sophomores who say, “hey, this composition thing is cool”. They may not have encountered it before, very few people are given the opportunity or think of it as an option. Composers are European, and they’ve been dead for a hundred years, you know. It’s just not an option for most high school students, and they first encounter the concept as freshmen. This is one of my roles—to make it a visible option. In some schools aspiring composition majors submit portfolios, and in other places simply make their intention known and they just become composition majors. I suppose this could be considered a form of poaching but I see it as an extended form of retention. People are interested in composition and it’s sort of a service. I see it as a service tool. Many continue to be music education majors or piano majors or whatever, who take a secondary interest in composition. Or they may decide to become composition concentrators, or they may decide to become dual concentrators and continue their original concentration as well as composition. I don’t really distinguish between these at all. Because frankly if somebody is a composition concentrator exclusively, then I worry about them. I tell all of my students, especially those who take that track, that this is a degree program, not a career path. Which is not to say that people shouldn’t be encouraged to make composition a career. You know, Robert’s talk this morning was fantastic about all the things that you can do to carve out opportunities. It exists, right? If we have the situation, as in so many applied studios, where you need have to have X number of students to justify your existence and then those students all think they’re going to have a job like yours, well then, that’s a Ponzi scheme, right? It’s not going to work. It’s exponential. And there are certainly not exponentially increasing academic positions.

So I encourage all my students to see composition as an auxiliary activity. It’s valuable; it’s extremely valuable in all musical professions. I think all band directors should be composers and arrangers, should be willing to step up to do that when the occasion demands. It’s something that’s of enormous value to applied teachers and the applied studio. If they’re comfortable composing, then they can encourage their students to compose and improvise. So I’m perfectly happy teaching other music majors and even non-majors, and I don’t think of those people as any less my students or any less my responsibility.

As far as internal recruiting, I think the main thing that I have to do is simply make composition viable and visible. We have concerts every year of the composers in class. This creates those opportunities. Again, it’s sort of an easy gig because just as people haven’t been presented with composition as an opportunity before getting to college, it doesn’t take much to make them feel like you’re doing a lot for them. They all performed music before in their ensembles and perhaps solo with their applied teacher before coming to college. But few of them have had the opportunity to have their music performed. And if you say here’s the composition class concert and you’re on it, and you have to have a piece ready by April so that we can perform it in May, they feel fantastic. They know this is their opportunity, and we give them the venue but typically we don’t give them any money for performers—it’s a cheap date. We still adulate composers in our musical society, and students feel very fortunate and cool to be doing it. So just creating an opportunity makes those people feel good. Then, these concerts allow our freshmen and sophomores to say “Oh, composers! I didn’t know composers could be 18-year-old living female human beings. Maybe I can do that too.” So that’s our internal recruitment.

As far as real recruitment, primary recruitment, getting people to come—it’s largely an extension of the same thing. We try to publicize our on-campus activities as much as we can. I encourage the students to do as much as possible—collaborating with theater students, writing music for plays, writing music for their friends’ video things. We also teach music for video, film scoring in essence, because that actually gets a lot more play and visibility than concerts, right? Theater people think twelve shows is routine. We do one concert and we’re done, and it’s mostly music people who show up in the first place. So music for video gets us a little bit more visibility.

Adjudication is a big thing. Vermont is lucky, we have the Vermont MIDI Project, now called Music-COMP. If you’re not familiar with it, it’s a mentoring program that’s run throughout the state where composer mentors, both remotely and in person, work with high school students from all areas of the state. So I’m involved with them, I do adjudication and also perform on their annual concert of student pieces, and adjudicate All-State competitions and things like the BMI contest. It’s not that anybody’s going to notice my being an adjudicator in itself; while it’s more work, I write the most constructive and detailed comments I can on and hope that eventually some of that comes back. I think a lot of this is what Robert was emphasizing in his assessment, which is that if we think narrowly about, at least in composition, simply recruiting for our studio, building up our studio, and how can we make this work for us, it’s not likely to go to go very far. But if I see it as, I’m just going to help these pre-college students however I can, and try to make opportunities for my students on-campus and off-campus, then eventually some of that comes back in the form of people being more aware of what we’re doing.