Abstract

Music had a prominent place in Seventeen from its first issue in September 1944, and music’s importance in the magazine reflects music’s importance in the lives of girls from the 1940s through the present day. Building on previous work by Schrum and Massoni, this study examines references to music in advertisements in Seventeen from the period of its inception to 1980. Advertisers simultaneously created and exploited the burgeoning and lucrative teen market. Musical references, found in texts, photographs, and illustrations, made consumer products especially appealing to upper-middle-class teenage girls.

V.J. MANZO

Seventeen is the most widely circulated magazine for American adolescent girls. It has a history that predates the rock ‘n’ roll era: the first issue was published in September 1944, and, according to Kelly Schrum, circulation had reached two-and-a-half million by July 1949 (the magazine is still in circulation) (139). In its advertisements and editorial content, Seventeen magazine reflected the ubiquitous presence of music as culture and consumer product in the lives of middle-class and upper-middle-class American teenage girls from the end of World War II to the dawn of the MTV era in August 1981. At the bottom of the cover of the earliest issues of Seventeen, one finds the words, “Young fashions & beauty, movies & music, ideas & people.” (The cover of the first issue is shown in Figure 1.) From its first issue, music had a prominent place in Seventeen, and music’s importance in the magazine reflects music’s importance in the lives of girls and young women from the 1940s through the present day. This study will examine references to music in advertisements in Seventeen during the period of its inception to 1980, through the peak of the rock’n’roll era, demonstrating how references to music in text and illustrations in these ads appealed to girls’ identities as teenage girls as well as to their aspirations for the future. In addition, this study will show how advertisers used music to make consumer products more appealing to upper-middle-class teenage girls.

Previous studies have addressed various aspects of Seventeen’s content from different eras. Gunilla Holm has focused on the magazine’s portrayals of schooling between 1966 and 1989; Kelly Massoni has examined its messages regarding occupations in 1992; Sandra Caron, William Halteman, Kate Peirce, and Jennifer Schlenker have completed feminist analyses of content in selected issues; Kelly Schrum has addressed advertising in Seventeen between 1944 and 1950; and Shelley Budgeon and Dawn Currie have studied references to women’s liberation in women’s and girls’ fashion magazines, including Seventeen, between 1951 and 1991 (Holm, 59-79; Massoni, 47-65; Schlenker et al, 135-149; Schrum, 134-163; Budgeon and Curry, 173).1The observations presented in this study are drawn from work with our own archive of just over one hundred issues of Seventeen from the specified date range. Our collection includes at least one issue from every calendar year 1944-1981. We have compiled this archive through Ebay over a period of several years.

Figure 1

Cover of the first issue of Seventeen magazine. The phrase “Young fashions & beauty, movies & music, ideas & people” appeared at the bottom of the cover of the first several issues and emphasized music’s privileged position in girl culture (Seventeen Sept 1944).

Advertisements in Seventeen include ads for music-related instruction and products (such as radios, stereos, phonographs, records, musical instruments, and ads for music schools and summer camps), as well as ads for non-music related products, such as clothing or cosmetics. Many ads for non-music related products include some reference to music, such as lyrics from a popular song, or a photo or illustration of young people playing instruments or singing. These music-oriented texts and images portray music as a vital and privileged part of teen culture and girl culture, and offer insight into music’s role in the life of the upper-middle-class teenage girls who were Seventeen’s target audience. Seventeen’s advertisements epitomize how adults perceived teenage girls during an era when the transition from girlhood to womanhood was fraught with changing societal expectations, and how advertisers’ assumptions regarding teens’ musical tastes shaped marketing to the teen consumer.

Before considering any advertisements, it is important to understand what a teenage girl was during the era in question. The image of the teenager had begun to emerge in the late 1930s and early 1940s, and by the 1950s, a teen subculture, defined by its economic power, participation in specific leisure activities, and music and fashion preferences, had codified. Thomas Hine, in his book The Rise and Fall of the American Teenager, explains the etymology of the term and its relationship to advertising:

References to a person in his or her teens had been part of the language since the 1600s. But such references had always described individuals. With the rise of the persuasion industries during the twentieth century, large groups of people were increasingly identified by single characteristics. People in their teens became "teens" or "teeners" or "teen-agers." They were largely in the same place--high school--sharing a common experience, and they were young and open to new things. They were, in short, easy to sell to. Moreover, the preferences formed when young often endure, which makes selling to teenagers a reasonable long-term investment.

The word "teen" has some interesting obsolete meanings that seem to echo faintly today. For seven centuries, "teen" meant a source of anger, irritation, or anxiety, an often apt description of one's offspring. It also meant barrier, and "teenage" (with a short a) was wood long enough for making a high fence--a meaning with resonance for young people who feel that being categorized as a teenager limits their freedom (Hine 1999, 9).

While this new subculture included boys and girls, the terms “youth,” “teen,” and “teenager” encountered in scholarship and the popular media during the immediate post-war era through the 1970s most often refers primarily or exclusively to teenage boys. Schrum explains:

In the 1950s, as teenage culture became a widespread, national obsession, scholars and media continued to write predominately about males, as reflected in James Gilbert’s work on societal response to juvenile delinquency and male youth culture. Rock and roll, drag racing, and rebellion were the territory of boys. . . . The scant literature on female adolescents addressed issues of behavior, appearance, and relationships and idealized teenage girls for their domesticity and dependence on consumer goods to alleviate feelings of inferiority. (Schrum 1998, 138).

Table 1

The word “teenager” enters American English (Schrum 1998, 18-19; 183 n. 25, 26)

|

1920s |

Advice literature for parents and educators used the terms “teen” and “teen-age” to refer to people aged thirteen to nineteen |

|

1920 |

M. V. O’Shea, The Trend of the Teens |

|

1923 |

Leora M. Blanchard, Teen-Age Tangles: A Teacher’s Experiences with Live Young People |

|

1930s |

Women’s Wear Daily and the Sears Roebuck Catalog use the terms “teen,” “teen-age girls,” and “teener” when marketing products for high school girls |

|

1930 |

“teenager” in American language for colloquial use, according to Dictionary of American Slang, 2nd ed. |

|

1941 |

“teenager” used in Popular Science Monthly; often cited as first use of the term |

|

1943-45 |

“teenager” is an index entry in The Readers’ Guide to Periodical Literature |

|

1945 |

“teenager” in American language for standard use, according to Dictionary of American Slang, 2nd ed. |

Words to designate this new demographic group began to enter American English in the 1920s, and were initially associated with education, psychology, and fashion merchandising. Table 1 shows a timeline of this terminology’s entry into American English from the 1920s through the mid-1940s.

Advertisements and editorial content in Seventeen reflected an image of teenage girls both as part of a larger teen subculture, and as girls whose individual identities were situated in a consumer-oriented domestic realm. Ads appealed to girls’ affiliation with their teenage peer groups, and to their future roles as middle-class and upper-middle-class wives and homemakers. With the emergence of a distinct teen culture, teenage tastes in a number of cultural commodities, including music, increasingly diverged from adult tastes. In the 1960s and 1970s, especially, ads in Seventeen including references to music more frequently allude to rock and other genres of popular music appealing to girls’ desire to fit in with other teenagers and to consider lifestyle choices different from those of their parents.

Although American youth culture in the postwar era is most often associated with the emergence of rock ‘n’ roll, Seventeen readers were exposed to a vast array of musical styles in the magazine’s pages, both in ads and editorial content. Record reviews columns regularly included classical and jazz as well as rock recordings, and many issues included feature-length articles on music or musicians. Readers could expect to encounter references to popular artists of the day as well as classical composers from every era.2Some feature-length articles on music and musicians in early issues of Seventeen include “No Curls for Harry James” (September 1944); “3X + 2Y = Woody Herman” (December 1944); “Swing’s Doctor of Philosophy, ” an article on Artie Shaw (April 1945); “Lionel ‘Tadlee Day Dit Dah’ Hampton” (October 1945); “There’s Music in the Air,” a history of Christmas carols (December 1945); an article on Gilbert and Sullivan entitled “Have You Met G & S?” (March 1946); “Gershwin, Modern, Immortal” (May 1946); “Mary Lou Williams” (September 1946); “He Made Sinatra Swoon,” an article on Eddie Fisher (August 1950);and a pair of articles, “Dixieland is Back” and “Country Music Never Went Away” (September 1950). Composers mentioned in issues of Seventeen include Bela Bartok, Alban Berg, Frederic Chopin, John Dowland, Cesar Franck, Giovanni Gabrieli, Ernst Krenek, Franz Josef Haydn, Paul Hindemith, Claudio Monteverdi, Cole Porter, Robert Schumann, Dmitri Shostakovich, and Kurt Weill. In addition to classical music, the popular music associated with those artists musicologist Elijah Wald refers to as “older, unrocking singers,” such as Pat Boone and Perry Como features prominently in Seventeen through the 1960s (Wald 2009, 8). Seventeen readers were presented with many choices in regard to their listening habits, and advertisers needed to be especially sensitive to how a carefully placed reference to a particular musical style could influence girls’ purchasing decisions.

Ads that featured girls as teenagers interacting with music often showed girls engaging in leisure time activities with other teenagers. Since teens’ music became a hallmark of teen culture during the postwar era, the types of non-music-related products whose advertising included references to music were most often those products that, like much of the popular music of the era, were created distinctly for, and marketed to, teenage girls; not married women, and not younger children.

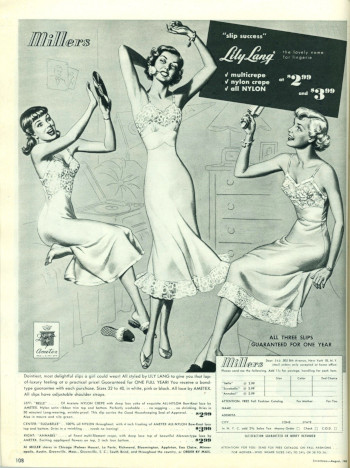

Ads for foundation garments (most of these ads were for bras and girdles) frequently included some sort of reference to music. Figures 2a, 2b, 2c show ads for foundation garments that include illustrations of girls interacting with music or musical artifacts. In the 1950s, companies were manufacturing and marketing foundation garments specifically for the teenage figure for the first time. In The Body Project: An Intimate History of American Girls, Joan Brumberg writes,

In an era distinguished by its worship of full-breasted women, interest in adolescent breasts came from all quarters: girls who wanted bras at an earlier age than ever before; mothers who believed that they should help a daughter acquire a ‘good’ figure; doctors who valued maternity over all other female roles; and merchandisers who saw profits in convincing girls and their parents that adolescent breasts needed to be tended in special ways. All of this interest coalesced in the 1950s to make the brassiere as critical as the sanitary napkin in making a girl’s transition into adulthood both modern and successful (Brumberg 1997, 111).

Figure 2a

Advertisement for slips shows girls dancing and using an LP as a makeshift tambourine (Seventeen Aug 1949)

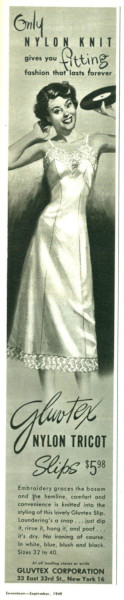

Figure 2b

Ad for slips shows a girl holding a record (Seventeen Sept 1949)

Figure 2c

Ad for Warners bra (Seventeen March 1955)

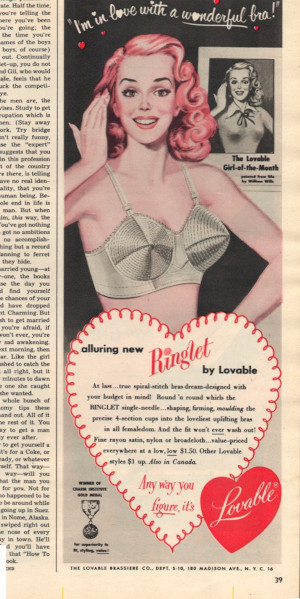

Broadway musicals and movie musicals were often referenced in ads for foundation garments in the 1950s. In the year 1955 alone, various issues of Seventeen featured ads for Peter Pan elastic girdles, The Wonderful Wizard of Bras, and the Bali-hi bra. The ad featured in Figure 3, from the October 1951 issue, paraphrases a line from a song from the musical South Pacific : “I'm in love with a wonderful bra!”

Figure 3

This ad for the Loveable Bra features a paraphrase of a line of a song from the musical South Pacific (Seventeen Oct 1951)

Associating the Loveable Bra with a song from South Pacific gave the former just the right sort of cultural clout and respectability. The musical South Pacific was on Broadway 1949-1954 and won the Pulitzer Prize for Drama in 1950, so this ad is well-timed. Judging from the pages of Seventeen in the late 1940s and early ‘50s, recordings of complete musicals and individual tunes from musicals were extremely popular at this time; articles and advertisements about and for Broadway musicals, cast recordings, and movie adaptations were featured heavily in the magazine in the late 1940s and throughout the 1950s. In the world of Seventeen, the link advertisers made between music and foundation garments was important. In order for an upper-middle-class teenage girl to grow up to be the right sort of woman, she needed to be shaped, molded, supported, and pointed in the right direction, and this process required both the right kind of music and the right kind of bra.3We do not believe it is an accident that we have yet to find an ad in any of these magazines from the 1940s and ‘50s for a “Bebop Bra” or a “Rockabilly Girdle.” Just as advertisers emphasized the importance of teenage girls having their own music to enjoy in their own rooms, they emphasized the necessity for these girls to have their own foundation garments, not those of a child or adult.

Although opportunities and expectations for girls changed dramatically between 1944 and 1981, a survey of Seventeen’s ads and editorial content suggests that the magazine’s readers during this period presumably maintained some common interests: they wanted to be popular, and were interested in the latest fashions and concerned with their personal appearance as a way of fitting in; they had some spending money of their own; and they were very interested in boys. Through the mid-1960s, Seventeen was careful to present a college education as a choice that was right for some, but not all, girls. Marriage and an identity as a wife and mother were presented as future vocation of every Seventeen reader; ads for china, silver, hope chests, and diamond rings can be found throughout the magazine even into the early 1980s.4Schrum observes that in the early years of the magazine, under Helen Valentine’s editorial supervision, Seventeen’s “emphasis on college and professional careers reflected the experiences of Helen Valentine and the editorial staff. . . . As a whole, however, career articles did not overshadow Seventeen’s emphasis on cleaning, decorating, shopping, cooking, or planning parties. But they did signify—and help legitimate—new opportunities for women.” (“Teena Means Business,” 153) According to the US Census Bureau, between 1947 and 1973, the median age of first marriage for women was consistently under 21, lower than at any other time during the twentieth century.5Estimated median age at first marriage, by sex: 1890 to the present, U.S. Census Bureau, internet release date 21 September 2006, http://www.census.gov/population/socdemo/hh-fam/ms2.pdf, accessed 28 July 2007. It was a fair assumption on the part of advertisers that for many of Seventeen’s readers, marriage was in the very near future

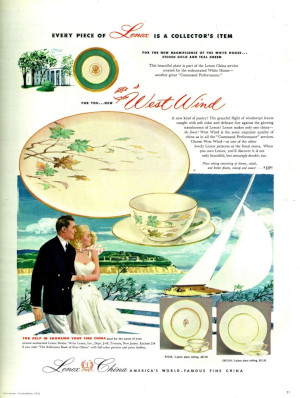

An advertisement shown in Figure 4 offers one example of how Seventeen readers may have perceived marriage, or rather, how advertisers typically presented marriage. This advertisement for Lenox china is from the September 1954 issue. We see a well-dressed, well-groomed young white couple standing on a deck overlooking the water, watching a boat with a huge sail; the location and the way the couple is dressed suggest a country club (possibly the site of an engagement party) or a posh resort (perhaps the couple is on their honeymoon). The lavish setting shown in this ad is a perfect backdrop for selling high-end china. Girls planning for this sort of lifestyle, or fantasizing about it, were probably eager to acquire some elegant tableware.

Figure 4

This ad for Lenox china depicts an idealized version of marriage (Seventeen Sept 1954)

What this ad is missing is any reference to music. References to popular music were rarely, if ever, employed to sell china, silver, or other domestic items to girls in the 1950s. The young woman in this ad—we hesitate to call her a girl—shows no signs of wanting to conform to her teenage peer group in regard to fashion, movies, or music; she is focused on the young man beside her, on the comfortable life they will share together, and on the larger-than-life plate floating in the sky above her head. When advertisers used popular music to promote products to girls, they knew that this music would connect girls to other teenagers, and that teenagers expected their friends to have the “right” clothes, shoes, make-up, and accessories. Schrum comments that Estelle Ellis, Seventeen’s first promotional director, used this idea of peer pressure as a selling point to potential advertisers: “Ellis always implied, and often explicitly stated, that teenage girls bought as a group—an advertisement strategically placed between its covers would sell to not just one girl, but the whole crowd” (Schrum 1998, 142). When advertisers wanted girls to buy things made specifically for teenage girls—training bras, for example—music, especially popular music, was an effective backdrop for the sales pitch, since the training bra, like a great deal of music, was a commodity consumed according to specific gender and generational affiliations. On the other hand, when advertisers wanted to appeal to girls’ plans for the future—their aspirations to be wives and homemakers, and to take on adult responsibilities—popular music was less helpful. A young bride-to-be choosing the china pattern that will be in her home for decades to come needs guidance from mature women—or from the china company, as is suggested in the lower left-hand corner of the ad—to make appropriate purchasing decisions. A reference to popular music in this context would distract from the seriousness with which girls were urged to make these types of consumer choices. Advertisers sometimes incorporated references to classical music when selling household items to girls. An ad from the December 1959 issue, shown in Figure 5, associates silverware with classical music and “high culture,” which were part of an adult world to which teenage girls aspired.

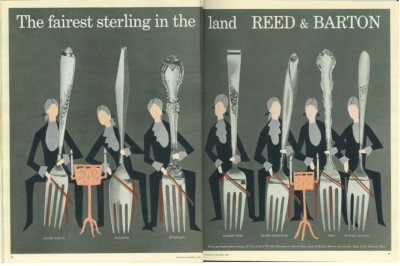

Figure 5

A two-page silverware ad associates silverware with classical music and “high culture,” aspects of an adult world to which teenage girls aspired (Seventeen Dec 1959)

A 1964 ad for Coffee of Brazil (shown in Figure 6) recommends bossa nova music for a Brazilian-themed coffee party; a brief lesson on bossa nova is included in the ad. In this ad, music is suggested as part of a social occasion. The context implies that girls should educate themselves on how to provide appropriate music for such occasions, as well as appropriate food, decorations, etc. Many references to music in Seventeen are in the context of music for specific social occasions; nearly every article and advertisement regarding party planning included some mention of arranging for the proper music, either live or recorded, to accompany the festivities. Party planning appealed both to the teenage girl concerned with her popularity, and to the girl who was looking forward to life as an upper-middle-class homemaker responsible for entertaining guests in her home. In this context, a knowledge of music was essential for young women, and ads like this one provided important impromptu venues for music instruction.

Girls were certainly being encouraged to listen to music while they were drinking coffee and wiggling into their training bras; when they were being encouraged to make their own music, some limitations were involved. One of those limitations involved the guitar. From the 1940s through the 1960s, girls were pictured in Seventeen standing near guitars, and watching boys playing guitars, but rarely was a girl shown holding or playing a guitar. Several scholars have addressed the both the acoustic and electric guitar in the twentieth century in the context of gender. In Girls Rock! Fifty Years of Women Making Music, Mina Carson, Tisa Lewis, and Susan M. Shaw discuss the history of the guitar from Renaissance Europe to the early twentieth century United States:

While the guitar began as a predominantly female instrument, its popularity in jazz, country, and big band music moved it more and more into the hands of men. And as the guitar became an increasingly male instrument, it also grew from its original eleven- to twelve-inch width to the massive sixteen-inch dreadnought introduced by Martin Guitar in 1916. The increased size mad the instrument more difficult for women to play. Guitarist Diane Ponzio notes, ‘If you have appreciable breasts, it’s just uncomfortable to play.’” (Carson 2004, 11-12)

Figure 6

This ad for Coffee of Brazil suggests samba music for a Brazilian-themed coffee party. Ads and articles that featured music as an aspect of party planning appealed to teenage girls’ desire to be popular and to their aspirations to be successful upper-middle class homemakers (Seventeen April 1964)

In the December 1949 fashion feature shown in Figures 7a and 7b, the guitar is a prop; the images shown here suggest that guitar playing is an activity associated with boys. This situation changed in the 1970s, thanks to a number of factors including the women’s movement and changing fashions for girls: not so much need to worry about your boyfriend feeling threatened because you can play as well as he can, and--with fashions no longer emphasizing an exaggerated female form--no more worries about figuring out how to hold a guitar while wearing a conical bra. In “Women Guitarists: Gender Issues in Alternative Rock,” John Strohm remarks on the relationship between the women’s movement, the folk revival, and the significance of the guitar in the 1960s and ‘70s:

The rediscovery of folk music empowered women because it sent the message that they could write and perform their music without male support …. Extraordinarily popular performers such as Odetta, Joan Baez, and Joni Mitchell commanded respect from their male contemporaries and provided strong role models for aspiring women guitarists (Strohm 2004, 185).

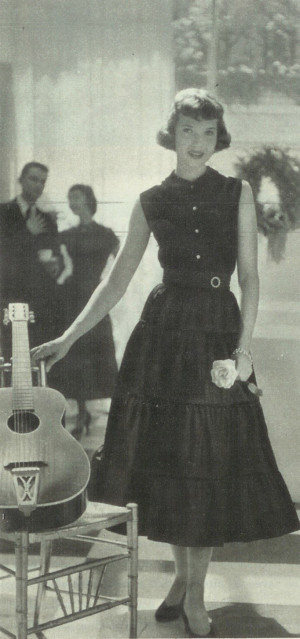

Figure 7a

In this photo from a fashion feature, the guitar is a prop. Girls were rarely shown playing, or even touching, guitars in Seventeen in the 1940s and ‘50s (Seventeen Dec 1949)

Figure 7b

In this photo from the same December 1949 fashion feature, it is significant that the boy, not the girls, is holding the guitar (Seventeen Dec. 1949)

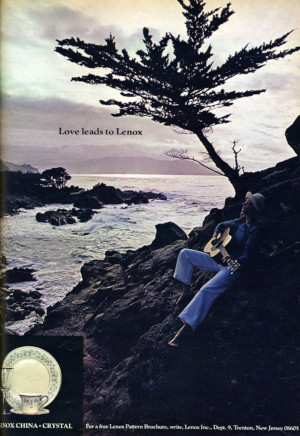

In an ad for Lenox china and crystal from the December 1975 issue (shown in Figure 8), we see a young woman, casually dressed and barefoot, leaning against some rocks on a secluded shore playing a guitar. Images like this one, connecting guitar playing with a relaxed lifestyle and an appreciation for the great outdoors (despite the fact that the ad is for china) are fairly common in the mid-1970s. The words “Love leads to Lenox,” featured prominently near the center of the full-page ad, indicate that the decision to purchase china and crystal has something to do with falling in love, although the object of the young woman’s desire is not pictured here. The girl’s guitar playing does not suggest any particular generational affiliation: in 1976, it was not at all uncommon for young mothers or teenage girls to play acoustic guitars; playing the guitar was not necessarily an activity a girl would have been expected to give up once she was married. Her guitar playing does not seem to be a gendered activity, either; the way she is dressed, her posture, and the way she holds the instrument suggest that the guitar as it is pictured here signifies neither masculine nor feminine; neither is it a countercultural instrument of social protest; it is simply a prop and a pastime that would have been familiar to the magazine’s readers. The guitar in this context, presented as a relatively neutral image, is remarkable when one considers that ten years earlier, such a photo would almost certainly not have appeared in an ad for china and crystal, and probably not in any other ad in Seventeen.6In the 1961 film Breakfast at Tiffany’s, a decidedly dressed-down Audrey Hepburn, wearing simple slacks and a sweatshirt, hair wrapped in a towel, is shown sitting in a window by a fire escape playing a guitar and singing “Moon River.” While such matters are highly subjective, we believe very few viewers would describe Hepburn’s femininity as being somehow compromised in this scene due to the presence of the guitar or any other factor. During this period in American girl culture, the guitar is not unequivocally unfeminine; rather, the brand of femininity depicted in and promoted by Seventeen tended to be stylized and exaggerated.

Figure 8

This ad for Lenox China equates guitar playing with a relaxed lifestyle (Seventeen Dec. 1975)

In Figure 9 we see another ad with a young woman and a guitar. This November 1976 ad for Fabergé eye makeup says: “If you were 23 and the composer of 100 songs–one of them a radio jingle aired daily, coast-to-coast–would you worry about your eyes being too small? Well, Beth Horton does. Or did. Before she opened her eyes to Fabergé’s super-smooth, moisturized Eye Makeup.” The reference to a young woman as a professional musician, and the photo of her holding her guitar, is notable because, again, it almost certainly would not have appeared in an ad for cosmetics (or anything else in Seventeen) ten years earlier. Progress, however, is slow: this ad makes it very clear that this young woman could not be successful without her makeup. The image of the guitar in this ad isn’t quite as neutral as in the previous photos. Here, the guitar is a tool with which a young woman is able to make a living. The guitar is a reference to this young woman’s skills as a musician and as a wage earner. Taken in a historical context, in 1976, these skills associate her with the women’s movement. The advertiser—Fabergé—appeals to girls’ belief that skill and good looks are important in the job market: whether you’re interested in landing that first date or landing that first job, you need to buy some make-up.

Figure 9

This ad for makeup features a woman as a successful professional musician (Seventeen Nov. 1976)

All of the images shown here feature acoustic, rather than electric guitars. The electric guitar carried stronger gendered connotations than its acoustic counterpart, especially after the rock and roll era. The images included in the pages of Seventeen portraying the guitar are important both because they helped girls identify and understand specific activities and objects that were associated with womanhood and femininity, and because they are historical documents that offer scholars a view of how the guitar was presented in a print publication intended for teenage girls. Mavis Bayton observes (2012, 266), “as girls grow up, they learn (from family, school, books, magazines, and above all, their friends) how to be ‘feminine’ and not to engage in ‘masculine’ activities. Playing the flute, violin, and piano is traditionally ‘feminine’, playing electric guitar is ‘masculine.’” In its first two decades, Seventeen adhered to cultural norms regarding the guitar by limiting the number and prominence of photos showing girls playing guitars. From the mid-1960s to the early 1980s, Seventeen continued to adhere to changing cultural standards by depicting girls holding and playing acoustic, rather than electric guitars.7Mavis Bayton has analyzed trade magazines for guitarists, studying how men and women are included in photographs and illustrations. See Mavis Bayton, “Women and the Electric Guitar,” (Bayton 2012, 266).

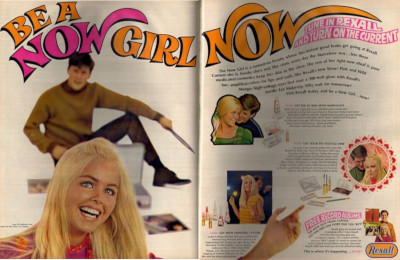

During the 1950s and ‘60s, advertisers used rock and roll references sparingly in their appeals to Seventeen’s upper-middle-class, mostly white readers. In the mid-1960s, rock culture slowly creeps into advertisements; terms like “beat” and “psychedelic” appear in ad copy, and editorial content reflects an acknowledgement that rock music is this generation’s lingua franca. A two-page May 1968 ad, shown in Figure 10, for Rexall drugs and Capitol records (a Lou Rawls album is shown in the lower right-hand corner), features psychedelic-influenced graphics and fashions. How ironic that this ad for a drug store chain incorporates a paraphrase of Timothy Leary’s famous “Turn on, tune in . . .” statement. Rexall offers a free Capitol record with every cosmetics purchase. This particular ad is remarkable because it is one of only two references in this issue to the previous year’s infamous Summer of Love, or to anything resembling hippie culture (the other reference being a somewhat over-the-top cautionary short story).

Figure 10

This ad for Rexall Drugs features psychedelic influenced graphics (Seventeen May 1968)

For girls coming of age during the post-World-War-II era, adolescence was often a treacherous tightrope between girlhood and womanhood. Pressure to become a wife and mother relatively early in life came from many sources, and contrasted sharply with the emergence of teen culture and rock ‘n’ roll. The examples included in this article demonstrate how advertisements in Seventeen during the post-war era used references to music to connect girls to their peer groups when peer pressure or a distinct identity as a teenager could help to sell a particular product. Advertisements—and editorial content as well—seem to suggest that the sound of wedding bells necessarily drowned out the sound of rock ‘n’ roll, although this suggestion seems to fade in the early 1970s, just as the average age of marriage begins to creep upward. Whether or not the ads in Seventeen are a precise indication of girls’ listening habits, Seventeen has been a vital part of girl culture for nearly seventy-five years, and its pages offer an important perspective on American teenage girls and their ongoing connection to worlds of culture and commerce through music.

NOTES

1. The observations presented in this study are drawn from work with our own archive of just over one hundred issues of Seventeen from the specified date range. Our collection includes at least one issue from every calendar year 1944-1981. We have compiled this archive through Ebay over a period of several years.

2. Some feature-length articles on music and musicians in early issues of Seventeen include “No Curls for Harry James” (September 1944); “3X + 2Y = Woody Herman” (December 1944); “Swing’s Doctor of Philosophy, ” an article on Artie Shaw (April 1945); “Lionel ‘Tadlee Day Dit Dah’ Hampton” (October 1945); “There’s Music in the Air,” a history of Christmas carols (December 1945); an article on Gilbert and Sullivan entitled “Have You Met G & S?” (March 1946); “Gershwin, Modern, Immortal” (May 1946); “Mary Lou Williams” (September 1946); “He Made Sinatra Swoon,” an article on Eddie Fisher (August 1950);and a pair of articles, “Dixieland is Back” and “Country Music Never Went Away” (September 1950).

3. We do not believe it is an accident that we have yet to find an ad in any of these magazines from the 1940s and ‘50s for a “Bebop Bra” or a “Rockabilly Girdle.”

4. Schrum observes that in the early years of the magazine, under Helen Valentine’s editorial supervision, Seventeen’s “emphasis on college and professional careers reflected the experiences of Helen Valentine and the editorial staff. . . . As a whole, however, career articles did not overshadow Seventeen’s emphasis on cleaning, decorating, shopping, cooking, or planning parties. But they did signify—and help legitimate—new opportunities for women.” (“Teena Means Business,” 153)

5. Estimated median age at first marriage, by sex: 1890 to the present, U.S. Census Bureau, internet release date 21 September 2006, http://www.census.gov/population/socdemo/hh-fam/ms2.pdf, accessed 28 July 2007.

6. In the 1961 film Breakfast at Tiffany’s, a decidedly dressed-down Audrey Hepburn, wearing simple slacks and a sweatshirt, hair wrapped in a towel, is shown sitting in a window by a fire escape playing a guitar and singing “Moon River.” While such matters are highly subjective, we believe very few viewers would describe Hepburn’s femininity as being somehow compromised in this scene due to the presence of the guitar or any other factor. During this period in American girl culture, the guitar is not unequivocally unfeminine; rather, the brand of femininity depicted in and promoted by Seventeen tended to be stylized and exaggerated.

7. Mavis Bayton has analyzed trade magazines for guitarists, studying how men and women are included in photographs and illustrations. See Mavis Bayton, “Women and the Electric Guitar,” (Bayton 2012, 266).

SOURCES CONSULTED

Bayton, Mavis. 2012. “Women and the Electric Guitar.” The Gender and Media Reader. Ed. Mary Celeste Kearny. New York: Routledge,.

Brumberg, Joan. 1997. The Body Project: An Intimate History of American Girls. New York: Random House.

Budgeon, Shelley, and Currie, Dawn H. 1995. "From feminism to postfeminism: Women's liberation in fashion magazines." Women's Studies International Forum 18.2: 173.

Carson, Mina, Tisa Lewis, and Susan M. Shaw. 2004. Girls Rock! Fifty Years of Women Making Music. New York and London: Lexington, KY: The University Press of Kentucky.

Cook, Daniel Thomas. 2004. The Commodification of Childhood: The Children’s Clothing Industry and the Rise of the Child Consumer. Durham: Duke University Press.

Currie, Dawn H. 2003. “Girl talk: Adolescent magazines and their readers.” The Audience Studies Reader. Ed. Will Brooker and Deborah Jermyn. New York: Routledge,. 243-253.

Fass, Paula S. 2007. Children of a New World: Society, Culture, and Globalization. New York and London: New York University Press.

Hine, Thomas. 1999. The Rise and Fall of the American Teenager. New York: Avon Books.

Holm, Gunilla. 1994. “Learning in Style : The Portrayal of Schooling in Seventeen Magazine.” Schooling in the Light of Popular Culture. Ed. Paul Farber, Eugene F. Provenzo, and Gunilla Holm. Albany: State University of New York Press, 59-79.

Massoni, Kelley. 2004. "Modeling Work: Occupational Messages in Seventeen Magazine." Gender & Society 18.1 (February 1): 47-65.

_____. 2006. “Teena Goes to Market: Seventeen Magazine and the Early Construction of the Teen Girl (as) Consumer.” The Journal of American Culture 29.1 (March): 31-42.

McCracken, Ellen. 1993. Decoding Women’s Magazines: From Mademoiselle to Ms. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Peirce, Kate. 1990. “A Feminist Theoretical Perspective on the Socialization of Teenage Girls Through Seventeen Magazine.” Sex Roles 23.9/10 (November): 491-500.

Savage, Jon. 2007. Teenage: The Creation of Youth Culture. New York: Viking.

Schlenker, Jennifer A., Sandra L. Caron, and William A. Halteman. 1998. “A feminist analysis of Seventeen magazine.” Sex Roles 38.1/2 (January): 135-149.

Schrum, Kelly. 1998. “’Teena Means Business’: Teenage Girls’ Culture and Seventeen Magazine, 1944-1950.” Delinquents and Debutantes: Twentieth-Century American girls’ cultures. Ed. Sherrie Inness. New York: New York University Press.

Seventeen Magazine. 1964. Advertisement for Coffee of Brazil, April.

_____. 1976. Advertisement for Fabergé Eye Makeup, November.

_____. 1940. Advertisement for Glowtex Slip, September.

_____. 1949. Advertisement for Lily Lane Slips, August.

_____. 1954. Advertisement for Lenox China, September.

_____. 1975. Advertisement for Lenox China, December.

_____. 1951. Advertisement for Loveable Bra, September.

_____. 1959. Advertisement for Reed and Barton Sterling tableware, December.

_____. 1955. Advertisement for Warner’s Bra, March.

_____. 1944. Cover, September.

_____. 1949. “Shined up and Pretty,” 70, December.

Strohm, John. 2004. “Women Guitarists: Gender Issues in Alternative Rock.” The Electric Guitar: A History of an American Icon. Ed. André Millard. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Valentine, Helen. 1982. “Oral History. William E. Wiener Oral History Library of The American Hewish Committee.” New York City Public Library, March 9.

Wald, Elijah. 2009. How the Beatles Destroyed Rock ‘n’ Roll: An Alternative History of American Popular Music. New York: Oxford University Press.

Whitely, Sheila. 2000. Women and Popular Music: Sexuality, Identity, and Subjectivity. London and New York: Routledge.

Zuckerman, Mary Ellen. 1998. A History of Popular Women’s Magazines in the United States: 1792-1995. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.